Targeted Liver Fibrosis Therapy: Evaluating Retinol-Modified Nanoparticles and Atorvastatin/JQ1-Loaded Nanoparticles for Deactivation of Activated Hepatic Stellate Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. NP Formulation and Characterization

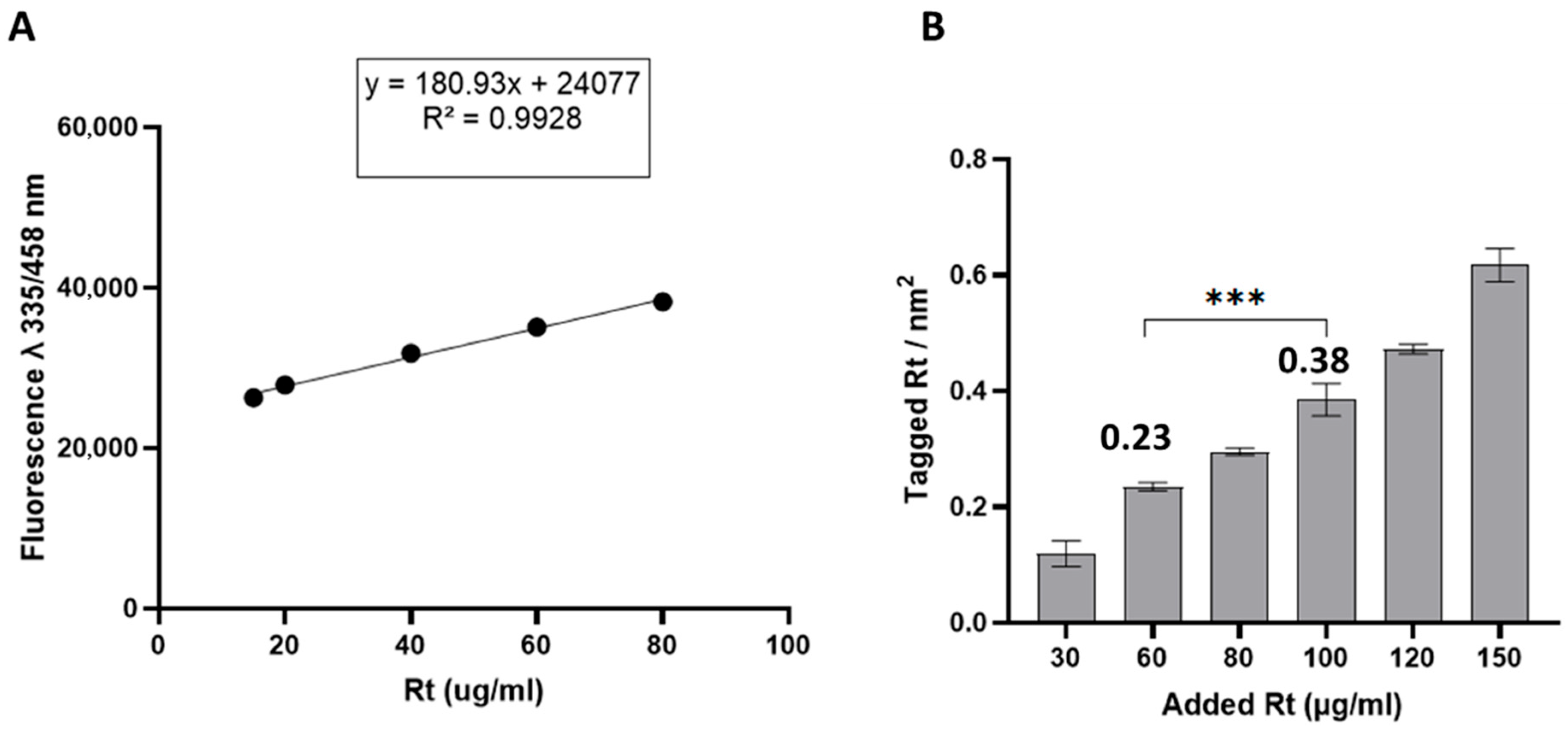

2.2. NP Modification with Different Densities of Retinol

Avogadro’s number

2.3. Drug Loading and Encapsulation Efficiency (EE%) Determination

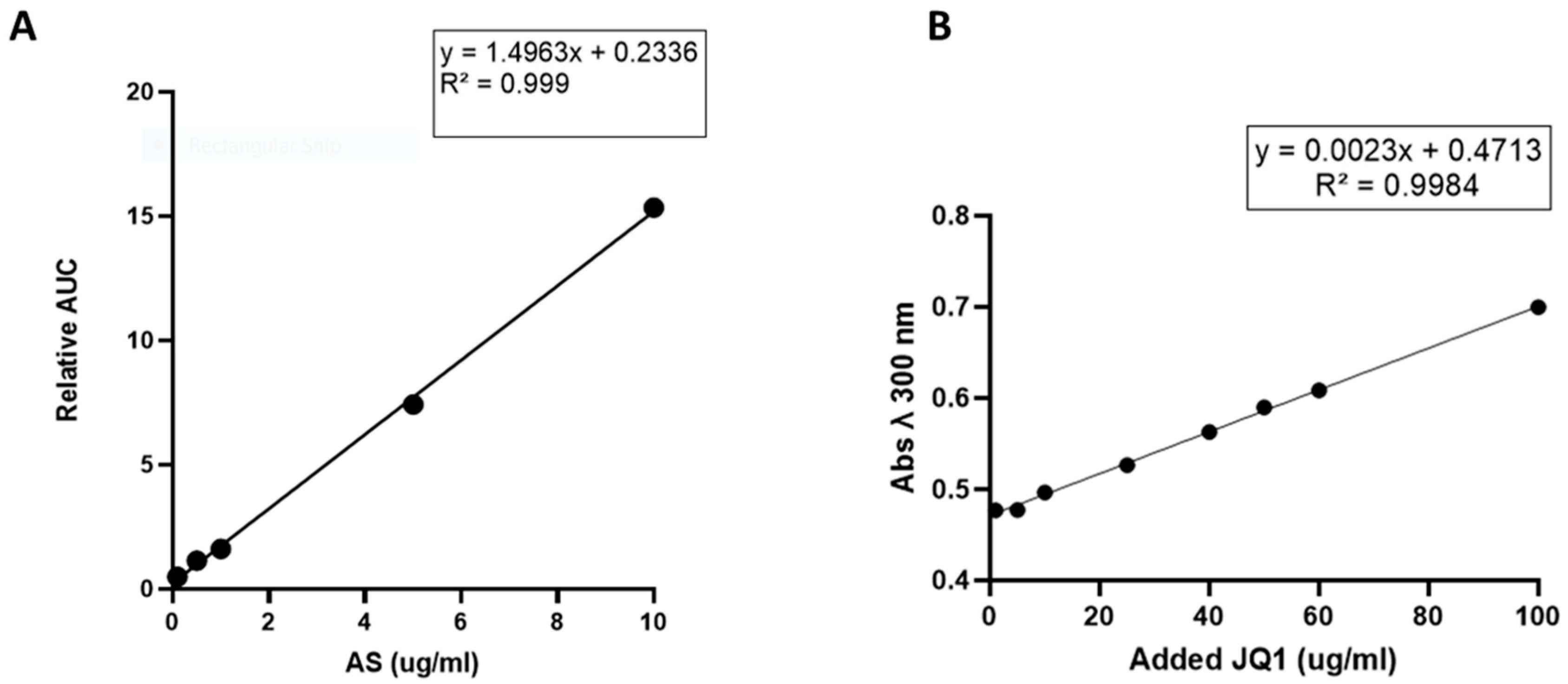

2.3.1. Preparation of Atorvastatin NPs (AS-NPs)

2.3.2. Preparation of (+)-JQ-1-NPs

2.4. Evaluation of NPs Uptake in GRX Cells

2.5. Effect of Retinol Tagging on NP Bio-Distribution

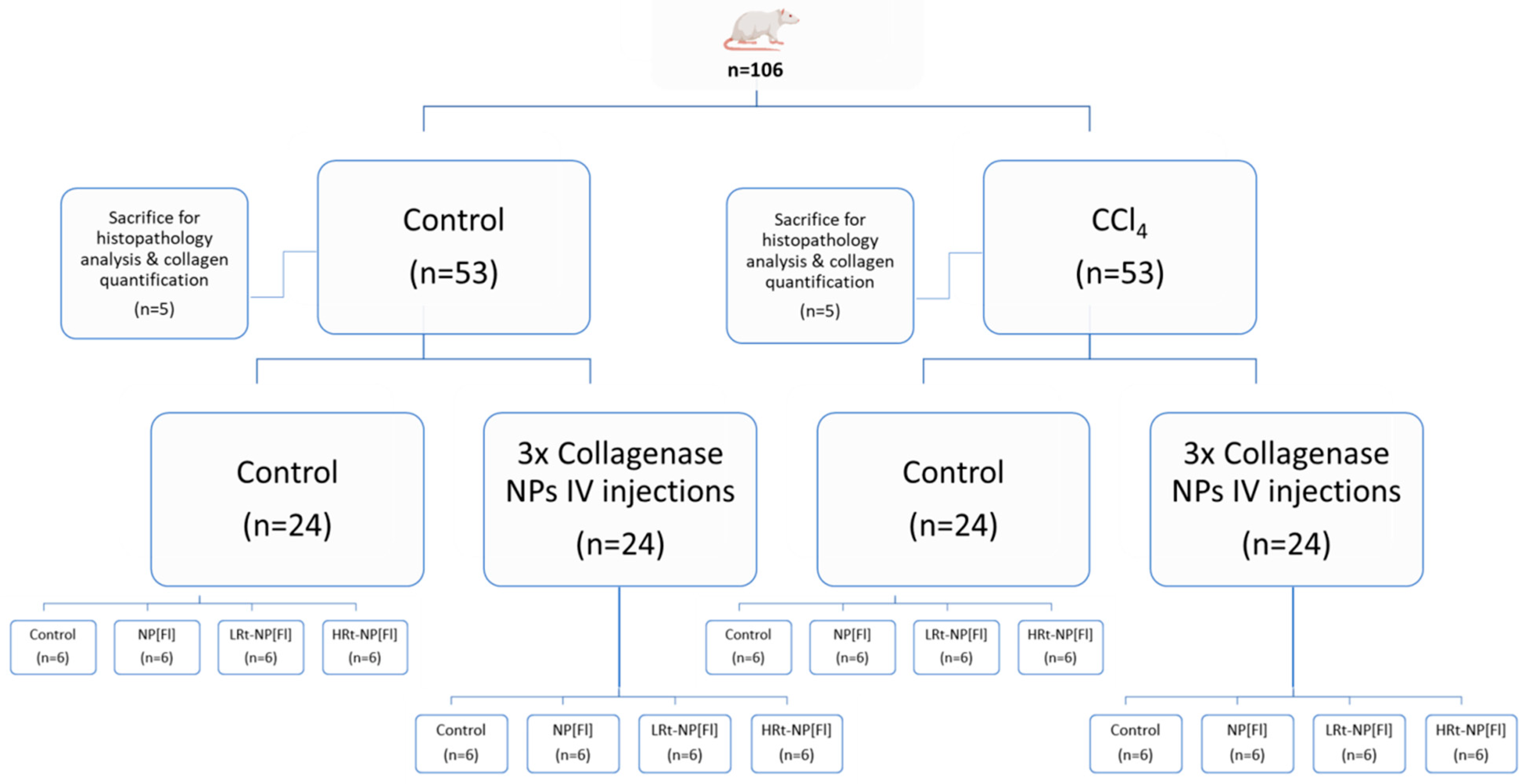

2.5.1. Induction of Liver Fibrosis

2.5.2. Histopathology Analysis

2.5.3. Collagen Quantification

2.5.4. NP Administration

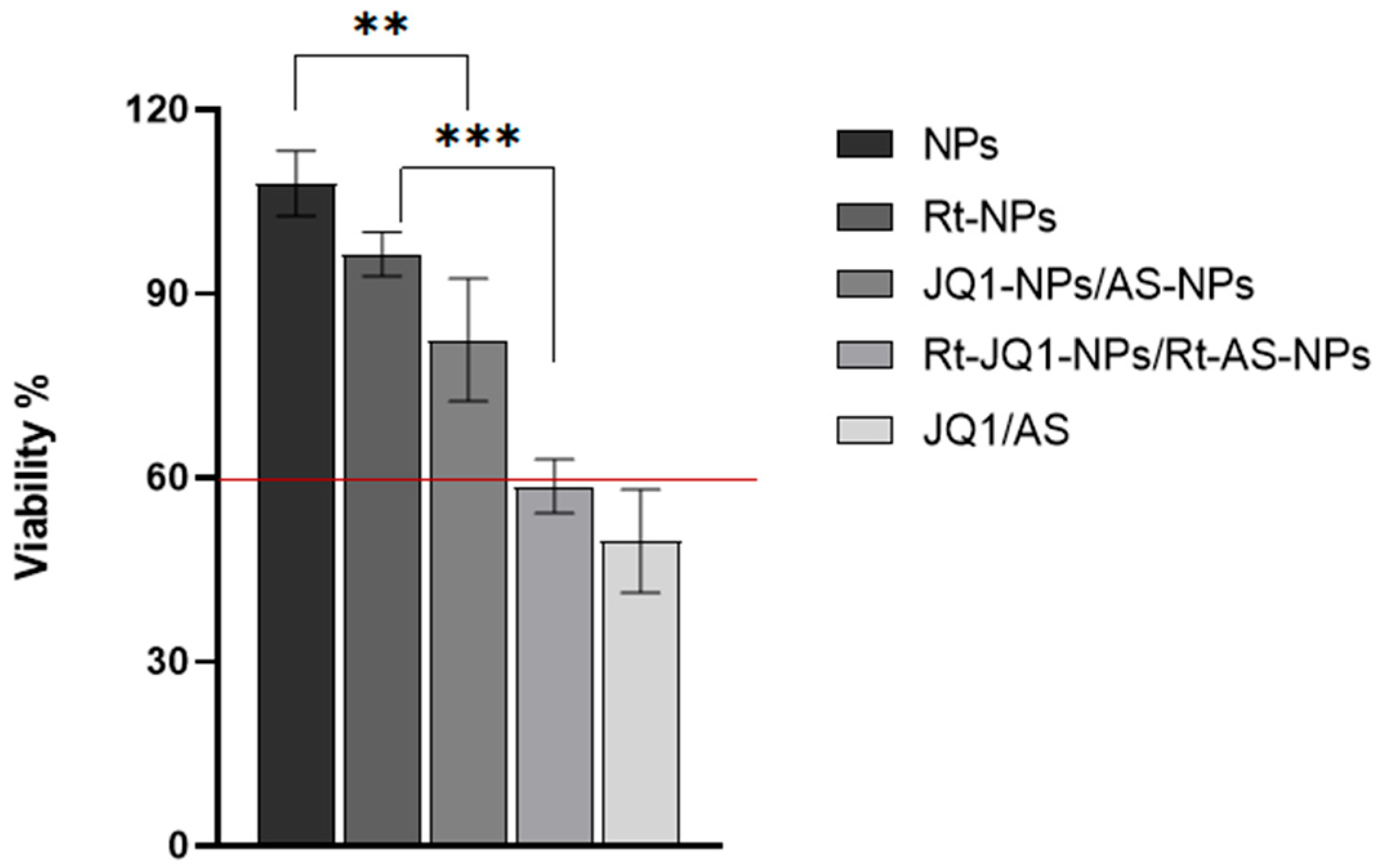

2.6. Effect of Drug-Loaded NPs on Cell Viability

2.7. Assessment of the Ability of Drug-Loaded NPs to Deactivate aHSCs

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Chitosan Nanoparticles Exhibit Easy Formulation, Tunable Functionalization and High Drug Loading Capacities

3.1.1. Chitosan NPs Characterization

3.1.2. Modification of NPs with Retinol

3.1.3. Determination of NPs Atorvastatin and JQ1 Loading Capacity and Encapsulation Efficiency (EE%)

3.2. Evaluation of the Impact of Retinol Tagging on GRX Cells Uptake Efficiency and Disease Targeting Ability

3.2.1. Evaluation of NP Uptake in GRX Cells

3.2.2. Confirmation of Liver Fibrosis Induction

3.2.3. Quantificationof Collagen Content in Liver Tissues of Healthy and Induced Mice

3.2.4. NP Bio-Distribution

3.3. Evaluation of the Efficiency of Rt-NPs for Selective Hepatic Accumulation in Fibrotic Versus Healthy Mice

3.4. Assessment of the Ability of AS- and JQ1-Loaded Rt-Modified NPs to Deactivate aHSCs

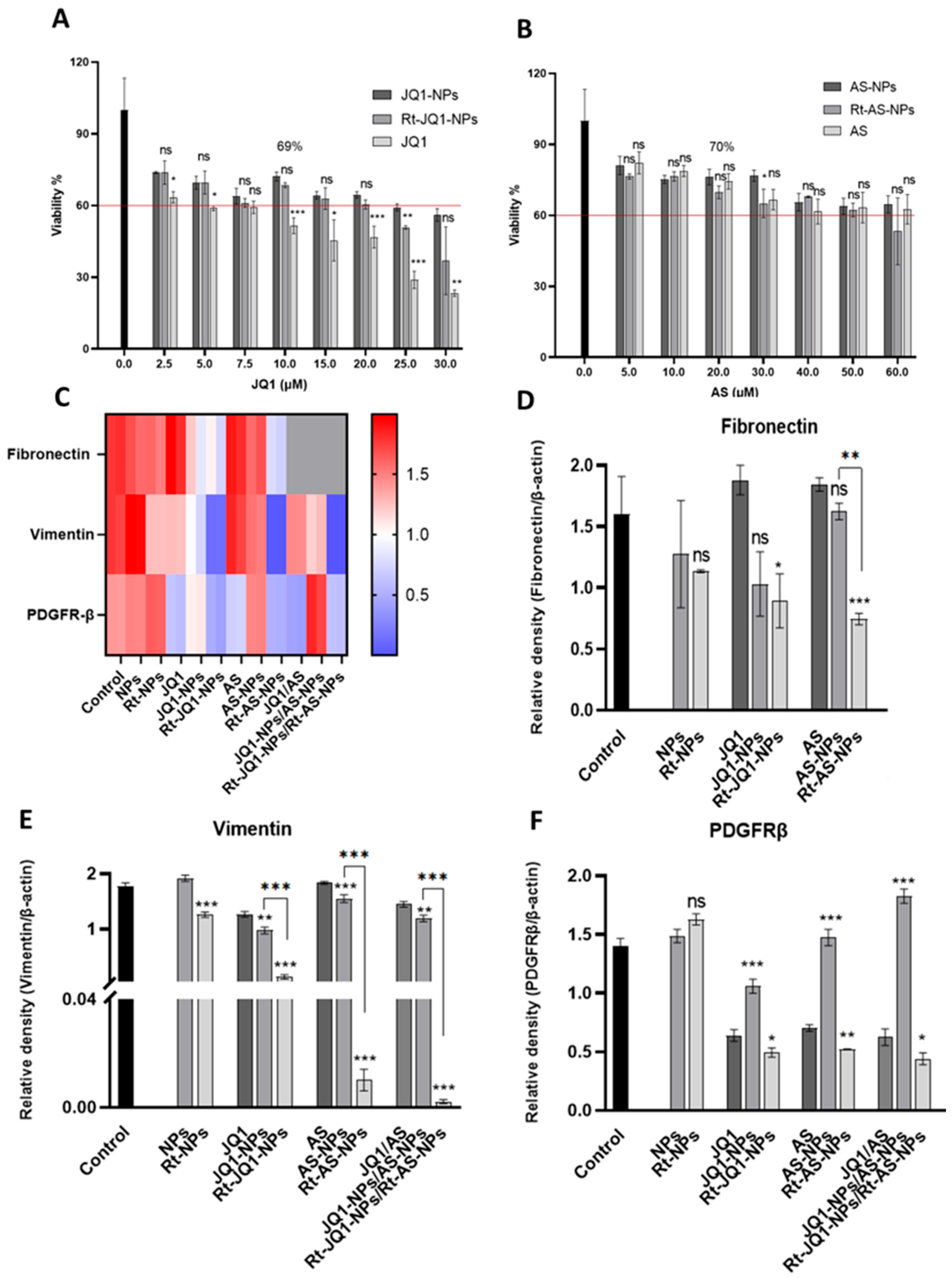

3.4.1. Effect of AS- and JQ1-Loaded NPs on Cell Viability

3.4.2. Assessment of the Ability of AS- and JQ1-Loaded NPs to Deactivate aHSCs

4. Discussion

4.1. NP Formulation, Functionalization, Drug Loading and Chemical Characterization

4.2. Evaluation of the Impact of Retinol Modification on Cellular Uptake

4.3. Evaluation of the Effect of Retinol Tagging on NP Bio-Distribution

4.4. Assessment of the Safety of Drug-Loaded NPs and Their Ability to Deactivate aHSCs

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | One-way analysis of variance test |

| AS | Atorvastatin |

| BDL | Bile duct ligation |

| BET | Bromodomain and extraterminal |

| BRD4 | Bromodomain-containing protein 4 |

| CDI | 1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| Fl | Fluorescein |

| GRX | Glutaredoxin cells, murine liver connective tissue cell line |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| HD | Hydrodynamic diameter |

| HRt-NPs | High Rt density |

| HSC | Hepatic stellate cell |

| IP | Intra-peritoneal |

| IV | Intra-venous |

| LRt-NPs | Low Rt density |

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PDGFR-β | Platelet-derived Growth Factor Receptor beta |

| RBP | Retinol binding protein |

| RES | Reticuloendothelial system |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| Rt | Retinol |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| TIMPs | Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases |

| TPP | Sodium tripolyphosphate |

| ZP | Zeta potential |

| α-SMA | α-smooth muscle actin |

Appendix A

| Experiment | Nanoparticles Used | Section/Line |

|---|---|---|

| Evaluation of NPs Uptake in GRX Cells | Comparison between fluorescein-loaded unmodified nanoparticles (Fl-NPs), fluorescein-loaded nanoparticles modified with low retinol density (LRt-Fl-NPs) and fluorescein-loaded nanoparticles modified with high retinol density (HRt-Fl-NPs), in vitro. | 2.4/152–192 |

| Effect of Retinol Tagging on NP Bio-Distribution | Comparison between fluorescein-loaded unmodified nanoparticles (Fl-NPs), fluorescein-loaded nanoparticles modified with low retinol density (LRt-Fl-NPs) and fluorescein-loaded nanoparticles modified with high retinol density (HRt-Fl-NPs), in vivo. | 2.5.4/245–270 |

| Effect of Drug-Loaded NPs on Cell Viability | Comparison between JQ1-loaded unmodified nanoparticles (JQ1-NPs), JQ1-loaded nanoparticles modified with low retinol density (Rt-JQ1-NPs), atorvastatin-loaded unmodified nanoparticles (AS-NPs), atorvastatin-loaded nanoparticles modified with low retinol density (Rt-AS-NPs), in vitro. | 2.6/271–283 |

| Assessment of the Ability of Drug-Loaded NPs to Deactivate aHSCs | Comparison between JQ1-loaded unmodified nanoparticles (JQ1-NPs), JQ1-loaded nanoparticles modified with low retinol density (Rt-JQ1-NPs), atorvastatin-loaded unmodified nanoparticles (AS-NPs), atorvastatin-loaded nanoparticles modified with low retinol density (Rt-AS-NPs), or combination of both, in vitro. | 2.7/284–312 |

| Nanoparticle | Size (nm) | Zeta Potential (mV) |

|---|---|---|

| NPs | 129 ± 22 | 41 ± 1 |

| LRt-NPs | 147 ± 10 | 37 ± 1 |

| HRt-NPs | 170 ± 20 | 29 ± 2 |

| JQ1-NPs | AS-NPs | JQ1-NPs/ AS-NPs | Rt-JQ1-NPs | Rt-AS-NPs | Rt-JQ1-NPs/ Rt-AS-NPs | JQ1 | AS | JQ1/AS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 72% | 76% | 82% | 69% | 70% | 59% | 51% | 74% | 49% |

References

- Antar, S.A.; Ashour, N.A.; Marawan, M.E.; Al-Karmalawy, A.A. Fibrosis: Types, Effects, Markers, Mechanisms for Disease Progression, and Its Relation with Oxidative Stress, Immunity, and Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaner, W.S.; O’Byrne, S.M.; Wongsiriroj, N.; Kluwe, J.; D’Ambrosio, D.M.; Jiang, H.; Schwabe, R.F.; Hillman, E.M.; Piantedosi, R.; Libien, J. Hepatic stellate cell lipid droplets: A specialized lipid droplet for retinoid storage. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 2009, 1791, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, S.L. Hepatic Stellate Cells: Protean, Multifunctional, and Enigmatic Cells of the Liver. Physiol. Rev. 2008, 88, 125–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, R.G. Cellular Sources of Extracellular Matrix in Hepatic Fibrosis. Clin. Liver Dis. 2008, 12, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, R.G. The role of matrix stiffness in regulating cell behavior. Hepatology 2008, 47, 1394–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, M.J.P. Reversibility of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis following treatment for hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 2002, 122, 1525–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, T.G.; King, L.Y.; Zheng, H.; Chung, R.T. Statin use is associated with a reduced risk of fibrosis progression in chronic hepatitis C. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraldes, J.G.; Albillos, A.; Bañares, R.; Turnes, J.; González, R.; García–Pagán, J.C.; Bosch, J. Simvastatin Lowers Portal Pressure in Patients With Cirrhosis and Portal Hypertension: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Gastroenterology 2009, 136, 1651–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolic, T.; Zivkovic, V.; Srejovic, I.; Stojic, I.; Jeremic, N.; Jeremic, J.; Radonjic, K.; Stankovic, S.; Obrenovic, R.; Djuric, D.; et al. Effects of atorvastatin and simvastatin on oxidative stress in diet-induced hyperhomocysteinemia in Wistar albino rats: A comparative study. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2018, 437, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoreshi, Z.A.S.; Kabirifar, R.; Khodarahmi, A.; Karimollah, A.; Moradi, A. The preventive effect of atorvastatin on liver fibrosis in the bile duct ligation rats via antioxidant activity and down-regulation of Rac1 and NOX1. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2020, 23, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; Zhang, X.; Hu, X.; Dong, M.; Pan, X.; Bian, J.; Zhou, Q. BRD4 inhibitor JQ1 inhibits and reverses mechanical injury-induced corneal scarring. Cell Death Discov. 2018, 4, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, M.S.; Haldar, S.M.; McKinsey, T.A. BRD4 inhibition for the treatment of pathological organ fibrosis. F1000Research 2017, 6, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, N.; Hah, N.; Yu, R.T.; Sherman, M.H.; Benner, C.; Leblanc, M.; He, M.; Liddle, C.; Downes, M.; Evans, R.M. BRD4 is a novel therapeutic target for liver fibrosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 15713–15718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.; McMahon, S.; Anand, P.; Shah, H.; Thomas, S.; Salunga, H.T.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Sahadevan, A.; Lemieux, M.E.; et al. BET bromodomain inhibition suppresses innate inflammatory and profibrotic transcriptional networks in heart failure. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaah5084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Mu, J.; Gong, Y.; Lu, C.; Zhao, Y.; He, T.; Qin, Z. Brd4 inhibition attenuates unilateral ureteral obstruction-induced fibrosis by blocking TGF-β-mediated Nox4 expression. Redox Biol. 2017, 11, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, H.; Yang, X.; Tian, J.; Wang, X.; Ji, Y.; El-Ashram, S.; Ren, C.; Shen, J.; Liu, M. JQ-1 ameliorates schistosomiasis liver fibrosis by suppressing JAK2 and STAT3 activation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 144, 112281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortuna, V.A.; Martucci, R.B.; Trugo, L.C.; Borojevic, R. Hepatic stellate cells uptake of retinol associated with retinol-binding protein or with bovine serum albumin. J. Cell. Biochem. 2003, 90, 792–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senoo, H.; Kojima, N.; Sato, M. Vitamin A-Storing Cells (Stellate Cells). Vitam. Horm. 2007, 75, 131–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, Y.; Murase, K.; Kato, J.; Kobune, M.; Sato, T.; Kawano, Y.; Takimoto, R.; Takada, K.; Miyanishi, K.; Matsunaga, T.; et al. Resolution of liver cirrhosis using vitamin A–coupled liposomes to deliver siRNA against a collagen-specific chaperone. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, H.T.T.; Dong, Z.; Su, L.; Boyer, C.; George, J.; Davis, T.P.; Wang, J. The Use of Nanoparticles to Deliver Nitric Oxide to Hepatic Stellate Cells for Treating Liver Fibrosis and Portal Hypertension. Small 2015, 11, 2291–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Jeong, H.; Park, S.; Yoo, W.; Choi, S.; Choi, K.; Lee, M.; Lee, M.; Cha, D.; Kim, Y.; et al. Fusion protein of retinol-binding protein and albumin domain III reduces liver fibrosis. EMBO Mol. Med. 2015, 7, 819–830. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, T.L.; Wang, P.W.; Hung, C.F.; Aljuffali, I.A.; Dai, Y.S.; Fang, J.Y. The impact of retinol loading and surface charge on the hepatic delivery of lipid nanoparticles. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2016, 141, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, C.; Zha, Y.; Hu, W.; Gao, Z.; Zang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Dong, L. Corona-Directed Nucleic Acid Delivery into Hepatic Stellate Cells for Liver Fibrosis Therapy. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 2405–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzat, A.A.; Tammam, S.N.; Hanafi, R.S.; Rashad, O.; Osama, A.; Abdelnaby, E.; Magdeldin, S.; Mansour, S. Different Serum, Different Protein Corona! the Impact of the Serum Source on Cellular Targeting of Folic Acid-Modified Chitosan-Based Nanoparticles. Mol. Pharm. 2022, 19, 1635–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R.; Tammam, S.N.; El Safy, S.; Abdel-Halim, M.; Asimakopoulou, A.; Weiskirchen, R.; Mansour, S. Prevention of hepatic stellate cell activation using JQ1-and atorvastatin-loaded chitosan nanoparticles as a promising approach in therapy of liver fibrosis. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2019, 134, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Safy, S.; Tammam, S.N.; Abdel-Halim, M.; Ali, M.E.; Youshia, J.; Boushehri, M.A.S.; Lamprecht, A.; Mansour, S. Collagenase loaded chitosan nanoparticles for digestion of the collagenous scar in liver fibrosis: The effect of chitosan intrinsic collagen binding on the success of targeting. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2020, 148, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinemeier, K.M.; Olesen, J.L.; Haddad, F.; Langberg, H.; Kjaer, M.; Baldwin, K.M.; Schjerling, P. Expression of collagen and related growth factors in rat tendon and skeletal muscle in response to specific contraction types. J. Physiol. 2007, 582, 1303–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borkham-Kamphorst, E.; Steffen, B.T.; Van de Leur, E.; Tihaa, L.; Haas, U.; Woitok, M.M.; Meurer, S.K.; Weiskirchen, R. Adenoviral CCN gene transfers induce in vitro and in vivo endoplasmic reticulum stress and unfolded protein response. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2016, 1863, 2604–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammam, S.N.; Azzazy, H.M.E.; Lamprecht, A. Biodegradable Particulate Carrier Formulation and Tuning for Targeted Drug Delivery. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2015, 11, 555–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noh, K.H.; Park, Y.M.; Kim, H.S.; Kang, T.H.; Song, K.-H.; Lee, Y.-H.; Byeon, Y.; Jeon, H.N.; Jung, I.D.; Shin, B.C.; et al. GM-CSF-loaded chitosan hydrogel as an immunoadjuvant enhances antigen-specific immune responses with reduced toxicity. BMC Immunol. 2014, 15, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzam, M.; El Safy, S.; Abdelgelil, S.A.; Weiskirchen, R.; Asimakopoulou, A.; de Lorenzi, F.; Lammers, T.; Mansour, S.; Tammam, S. Targeting Activated Hepatic Stellate Cells Using Collagen-Binding Chitosan Nanoparticles for siRNA Delivery to Fibrotic Livers. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cogger, V.C.; O’Reilly, J.N.; Warren, A.; Le Couteur, D.G. A Standardized Method for the Analysis of Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells and Their Fenestrations by Scanning Electron Microscopy. J. Vis. Exp. 2015, 98, 52698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodde, M.S.; Divase, G.T.; Devkar, T.B.; Tekade, A.R. Solubility and Bioavailability Enhancement of Poorly Aqueous Soluble Atorvastatin: In Vitro, Ex Vivo, and In Vivo Studies. Biomed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 463895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jostes, S.; Nettersheim, D.; Fellermeyer, M.; Schneider, S.; Hafezi, F.; Honecker, F.; Schumacher, V.; Geyer, M.; Kristiansen, G.; Schorle, H. The bromodomain inhibitor JQ1 triggers growth arrest and apoptosis in testicular germ cell tumours in vitro and in vivo. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2017, 21, 1300–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoudi, E.; Soleimani, M.; Zarinfard, G.; Homayoun, M.; Bakhtiari, M. The effects of chitosan-loaded JQ1 nanoparticles on OVCAR-3 cell cycle and apoptosis-related gene expression. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 19, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Jain, A.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Z.; Cheng, K. Targeted Drug Delivery to Hepatic Stellate Cells for the Treatment of Liver Fibrosis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2019, 370, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Kawaguchi, R. The Membrane Receptor for Plasma Retinol-Binding Protein, A New Type of Cell-Surface Receptor. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2011, 288, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, S.K.; Schüler, H.M.; Petersen, K.V.; Tesauro, C.; Knudsen, B.R.; Pedersen, F.S.; Krus, F.; Buhl, E.M.; Roeb, E.; Roderfeld, M.; et al. Genetic and Molecular Characterization of the Immortalized Murine Hepatic Stellate Cell Line GRX. Cells 2022, 11, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, C.P.; Fortuna, V.A.; Margis, R.; Trugo, L.; Borojevic, R. Retinol uptake and metabolism, and cellular retinol binding protein expression in an in vitro model of hepatic stellate cells. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1998, 187, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senoo, H.; Smeland, S.; Malaba, L.; Bjerknes, T.; Stang, E.; Roos, N.; Berg, T.; Norum, K.R.; Blomhoff, R. Transfer of retinol-binding protein from HepG2 human hepatoma cells to cocultured rat stellate cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 3616–3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepreux, S.; Bioulac-Sage, P.; Gabbiani, G.; Sapin, V.; Housset, C.; Rosenbaum, J.; Balabaud, C.; Desmoulière, A. Cellular retinol-binding protein-1 expression in normal and fibrotic/cirrhotic human liver: Different patterns of expression in hepatic stellate cells and (myo)fibroblast subpopulations. J. Hepatol. 2004, 40, 774–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchio, K.; Tuchweber, B.; Manabe, N.; Gabbiani, G.; Rosenbaum, J.; Desmoulière, A. Cellular Retinol-Binding Protein-1 Expression and Modulation during In Vivo and In Vitro Myofibroblastic Differentiation of Rat Hepatic Stellate Cells and Portal Fibroblasts. Lab. Investig. 2002, 82, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senoo, H.; Yoshikawa, K.; Morii, M.; Miura, M.; Imai, K.; Mezaki, Y. Hepatic stellate cell (vitamin A-storing cell) and its relative—Past, present and future. Cell Biol. Int. 2010, 34, 1247–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Dong, Y.; Ma, L. Co-encapsulation of collagenase type I and silibinin in chondroitin sulfate coated multilayered nanoparticles for targeted treatment of liver fibrosis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 263, 117964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Wang, X.; Xing, W.; Li, F.; Liang, M.; Li, K.; He, Y.; Wang, J. An update on animal models of liver fibrosis. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1160053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, N.; Ali, H.; Ateeq, M.; Bertino, M.F.; Shah, M.R.; Franzel, L. Silymarin coated gold nanoparticles ameliorates CCl 4 -induced hepatic injury and cirrhosis through down regulation of hepatic stellate cells and attenuation of Kupffer cells. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 9012–9020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortea, J.I.; Fernández-Mena, C.; Puerto, M.; Ripoll, C.; Almagro, J.; Bañares, J.; Bellón, J.M.; Bañares, R.; Vaquero, J. Comparison of Two Protocols of Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Cirrhosis in Rats—Improving Yield and Reproducibility. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholten, D.; Trebicka, J.; Liedtke, C.; Weiskirchen, R. The carbon tetrachloride model in mice. Lab. Anim. 2015, 49 (Suppl. S1), 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karsdal, M.A.; Daniels, S.J.; Nielsen, S.H.; Bager, C.; Rasmussen, D.G.K.; Loomba, R.; Surabattula, R.; Villesen, I.F.; Luo, Y.; Shevell, D.; et al. Collagen biology and non-invasive biomarkers of liver fibrosis. Liver Int. 2020, 40, 736–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, F.; Arthur, M.; Iredale, J. Developing strategies for liver fibrosis treatment. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2002, 11, 1575–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Hernandez, A.; Amenta, P.S. The hepatic extracellular matrix. Virchows Arch. A Pathol. Anat. Histopathol. 1993, 423, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, N.M.; El Aziz, F.M.A.; Deghady, A.; Abaza, M.H.; Ellakany, W.I. Tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloprotinase-1 and collagen type IV in HCV-associated cirrhosis and grading of esophageal varices. Egypt. Liver J. 2024, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Lan, T.; Han, Y.; Yang, N.; Wang, C.; Tao, M.; Li, H.; Song, Y.; Ma, X. Protective Effects of Phytic Acid on CCl4-Induced Liver Fibrosis in Mice. Arshad MS, editor. J. Food Biochem. 2023, 2023, 6634450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, E.A.; Badr, G.; Hassan, K.A.-H.; Waly, H.; Ozdemir, B.; Mahmoud, M.H.; Alamery, S. Induction of liver fibrosis by CCl4 mediates pathological alterations in the spleen and lymph nodes: The potential therapeutic role of propolis. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 1272–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zein, N.; Yassin, F.; Ayoub, H.G.; Elewa, Y.H.A.; Mohamed, S.K.A.; Mahmoud, M.H.; Elfeky, M.; Batiha, G.E.-S.; Zahran, M.H. In vivo investigation of the anti-liver fibrosis impact of Balanites aegyptiaca/ chitosan nanoparticles. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 172, 116193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzoheiry, A.; Ayad, E.; Omar, N.; Elbakry, K.; Hyder, A. Anti-liver fibrosis activity of curcumin/chitosan-coated green silver nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wary, R.; Sivaraj, S.; Gurukarthikeyan, P.R.K.; Mari, S.; SURAJa, G.D.; Kannayiram, G.O.M.A.T.H.I. Chitosan gallic acid microsphere incorporated collagen matrix for chronic wounds: Biophysical and biochemical characterization. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 6, 94–100. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, C.M.; Kalisvaart, A.C.; Kung, T.F.; Maisey, D.R.; Klahr, A.C.; Dickson, C.T.; Colbourne, F. The collagenase model of intracerebral hemorrhage in awake, freely moving animals: The effects of isoflurane. Brain Res. 2020, 1728, 146593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, B.; Alter, H.J.; Zhang, Z.-C.; Shih, J.W.-K.; Esteban, J.M.; Sun, T.; Yang, Y.-S.; Qiu, Q.; Liu, X.-L.; Yao, L.; et al. Reversibility of experimental rabbit liver cirrhosis by portal collagenase administration. Lab. Investig. 2005, 85, 992–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouchi, H.; Fujita, M.; Ikegame, S.; Ye, Q.; Inoshima, I.; Harada, E.; Kuwano, K.; Nakanishi, Y. The role of collagenases in experimental pulmonary fibrosis. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008, 21, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas, M.R.; Baeza, A.; Usategui, A.; Ortiz-Romero, P.L.; Pablos, J.L.; Vallet-Regí, M. Collagenase nanocapsules: An approach to fibrosis treatment. Acta Biomater. 2018, 74, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolor, A.; Szoka, F.C. Digesting a Path Forward: The Utility of Collagenase Tumor Treatment for Improved Drug Delivery. Mol. Pharm. 2018, 15, 2069–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Lin, J. Treatment of oral submucous fibrosis by collagenase: Effects on oral opening and eating function. Oral Dis. 2007, 13, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkilany, A.M.; Zhu, L.; Weller, H.; Mews, A.; Parak, W.J.; Barz, M.; Feliu, N. Ligand density on nanoparticles: A parameter with critical impact on nanomedicine. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2019, 143, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhari, A.; Baoum, A.; Siahaan, T.J.; Le, K.B.; Berkland, C. Controlling ligand surface density optimizes nanoparticle binding to ICAM-1. J. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 100, 1045–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, K.; Maitani, Y. Effects of Polyethylene Glycol Spacer Length and Ligand Density on Folate Receptor Targeting of Liposomal Doxorubicin In Vitro. J. Drug Deliv. 2011, 2011, 160967. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tammam, S.N.; Azzazy, H.M.; Breitinger, H.G.; Lamprecht, A. Chitosan Nanoparticles for Nuclear Targeting: The Effect of Nanoparticle Size and Nuclear Localization Sequence Density. Mol. Pharm. 2015, 12, 4277–4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, D.R.; Poloukhtine, A.; Popik, V.; Tsourkas, A. Effect of ligand density, receptor density, and nanoparticle size on cell targeting. Nanomedicine 2013, 9, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanotti, G.; Berni, R. Plasma Retinol-Binding Protein: Structure and Interactions with Retinol, Retinoids, and Transthyretin. Vitam. Horm. 2004, 69, 271–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.K.F.; Chan, M.H.M.; Tai, M.H.L.; Lam, C.W.K. Hepatorenal syndrome. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 2007, 28, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- DiKun, K.M.; Gudas, L.J. Vitamin A and retinoid signaling in the kidneys. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 248, 108481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvente, C.J.; Sehgal, A.; Popov, Y.; Kim, Y.O.; Zevallos, V.; Sahin, U.; Diken, M.; Schuppan, D. Specific hepatic delivery of procollagen α1(I) small interfering RNA in lipid-like nanoparticles resolves liver fibrosis. Hepatology 2015, 62, 1285–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, H.; Alcalá-Alcalá, S.; Caballero-Florán, I.H.; Bernal-Chávez, S.A.; Ávalos-Fuentes, A.; González-Torres, M.; Carmen, M.G.-D.; Figueroa-González, G.; Reyes-Hernández, O.D.; Floran, B.; et al. A Reevaluation of Chitosan-Decorated Nanoparticles to Cross the Blood-Brain Barrier. Membranes 2020, 10, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprifico, A.E.; Foot, P.J.S.; Polycarpou, E.; Calabrese, G. Overcoming the Blood-Brain Barrier: Functionalised Chitosan Nanocarriers. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.H.; Wang, Z.Y.; Sun, C.S.; Wang, C.Y.; Jiang, T.Y.; Wang, S.L. Trimethylated chitosan-conjugated PLGA nanoparticles for the delivery of drugs to the brain. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 908–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourtalebi Jahromi, L.; Moghaddam Panah, F.; Azadi, A.; Ashrafi, H. A mechanistic investigation on methotrexate-loaded chitosan-based hydrogel nanoparticles intended for CNS drug delivery: Trojan horse effect or not? Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 125, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlew, B.S.; Weber, K.T. Connective Tissue and the Heart. Cardiol. Clin. 2000, 18, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, J.-B.; Fan, Q.-Q.; Xing, L.; Cui, P.-F.; He, Y.-J.; Zhu, J.-C.; Wang, L.; Pang, T.; Oh, Y.-K.; Zhang, C.; et al. Vitamin A-decorated biocompatible micelles for chemogene therapy of liver fibrosis. J. Control. Release 2018, 283, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Yang, C.; Zhang, H.; Ma, J.; Jia, J.; Tang, X.; Zeng, J.; Chong, T.; Wang, X.; He, D.; et al. BET inhibitor JQ1 suppresses cell proliferation via inducing autophagy and activating LKB1/AMPK in bladder cancer cells. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 4792–4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggisano, V.; Celano, M.; Malivindi, R.; Barone, I.; Cosco, D.; Mio, C.; Mignogna, C.; Panza, S.; Damante, G.; Fresta, M.; et al. Nanoparticles Loaded with the BET Inhibitor JQ1 Block the Growth of Triple Negative Breast Cancer Cells In Vitro and In Vivo. Cancers 2019, 12, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celano, M.; Gagliardi, A.; Maggisano, V.; Ambrosio, N.; Bulotta, S.; Fresta, M.; Russo, D.; Cosco, D. Co-Encapsulation of Paclitaxel and JQ1 in Zein Nanoparticles as Potential Innovative Nanomedicine. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarbassova, G.; Nurlan, N.; Al shammari, B.R.; Francis, N.; Alshammari, M.; Aljofan, M. Investigating potential anti-proliferative activity of different statins against five cancer cell lines. Saudi Pharm. J. 2023, 31, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidar, M.K.; Demirbolat, G.M.; Timur, S.S.; Gürsoy, R.N.; Nemutlu, E.; Ulubayram, K.; Öner, L.; Eroğlu, H. Atorvastatin-loaded nanosprayed chitosan nanoparticles for peripheral nerve injury. Bioinspired, Biomim. Nanobiomaterials 2020, 9, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.W.; Wu, T.H.; Lin, T.Y.; Chen, M.H.; Yeh, C.T.; Pan, T.L. Characterization of the Roles of Vimentin in Regulating the Proliferation and Migration of HSCs during Hepatic Fibrogenesis. Cells 2019, 8, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mòdol, T.; Brice, N.; de Galarreta, M.R.; Garzón, A.G.; Iraburu, M.J.; Martínez-Irujo, J.J.; López-Zabalza, M.J. Fibronectin Peptides as Potential Regulators of Hepatic Fibrosis Through Apoptosis of Hepatic Stellate Cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2015, 230, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-Y.; Liu, R.-X.; Hou, F.; Cui, L.-J.; Li, C.-Y.; Chi, C.; Yi, E.; Wen, Y.; Yin, C.-H. Fibronectin expression is critical for liver fibrogenesis in vivo and in vitro. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 14, 3669–3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altrock, E.; Sens, C.; Wuerfel, C.; Vasel, M.; Kawelke, N.; Dooley, S.; Sottile, J.; Nakchbandi, I.A. Inhibition of fibronectin deposition improves experimental liver fibrosis. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attallah, A.M.; Abdallah, S.O.; Omran, M.M.; Farid, K.; Nasif, W.A.; Shiha, G.E.; Abdel-Aziz, A.-A.F.; Rasafy, N.; Shaker, Y.M. Diagnostic value of fibronectin discriminant score for predicting liver fibrosis stages in chronic hepatitis C virus patients. Ann. Hepatol. 2013, 12, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greuter, T.; Shah, V.H. Hepatic sinusoids in liver injury, inflammation, and fibrosis: New pathophysiological insights. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 51, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, J.M.; Bayless, K.J. Vimentin as an Integral Regulator of Cell Adhesion and Endothelial Sprouting. Microcirculation 2014, 21, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivaska, J.; Pallari, H.M.; Nevo, J.; Eriksson, J.E. Novel functions of vimentin in cell adhesion, migration, and signaling. Exp. Cell Res. 2007, 313, 2050–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Dai, F.; Liu, Y.; Yu, X.; Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Yao, W. RhoA/ROCK signaling regulates smooth muscle phenotypic modulation and vascular remodeling via the JNK pathway and vimentin cytoskeleton. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 133, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.M.; Zhang, W.S.; Yang, Z.G. Vimentin (VIM) predicts advanced liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B patients: A random forest-derived analysis. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 5164–5177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Wang, L.; Wang, M.; Zhou, S.; Lu, Y.; Cui, H.; Racanelli, A.C.; Zhang, L.; Ye, T.; Ding, B.; et al. Targeting fibrosis: Mechanisms and clinical trials. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, H.-Z.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, W.-Y.; Zhang, H.-H.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, S.-Z.; Fang, J.; Yu, C.-H. PDGF signaling pathway in hepatic fibrosis pathogenesis and therapeutics. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 7879–7889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klinkhammer, B.M.; Floege, J.; Boor, P. PDGF in organ fibrosis. Mol. Asp. Med. 2018, 62, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocabayoglu, P.; Lade, A.; Lee, Y.A.; Dragomir, A.-C.; Sun, X.; Fiel, M.I.; Thung, S.; Aloman, C.; Soriano, P.; Hoshida, Y.; et al. β-PDGF receptor expressed by hepatic stellate cells regulates fibrosis in murine liver injury, but not carcinogenesis. J. Hepatol. 2015, 63, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambrecht, J.; Verhulst, S.; Mannaerts, I.; Sowa, J.P.; Best, J.; Canbay, A.; Reynaert, H.; van Grunsven, L.A. A PDGFRβ-based score predicts significant liver fibrosis in patients with chronic alcohol abuse, NAFLD and viral liver disease. EBioMedicine 2019, 43, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkham-Kamphorst, E.; van Roeyen, C.R.C.; Ostendorf, T.; Floege, J.; Gressner, A.M.; Weiskirchen, R. Pro-fibrogenic potential of PDGF-D in liver fibrosis. J. Hepatol. 2007, 46, 1064–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaafsma, D.; McNeill, K.D.; Mutawe, M.M.; Ghavami, S.; Unruh, H.; Jacques, E.; Laviolette, M.; Chakir, J.; Halayko, A.J. Simvastatin inhibits TGFβ1-induced fibronectin in human airway fibroblasts. Respir. Res. 2011, 12, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, M.; Kayalar, O.; Atahan, E.; Oztay, F. Anti-fibrotic effect of Atorvastatin on the lung fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. Eur. Respir. J. 2018, 52, PA991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.S.; Chaudhary, D.K.; Mohan, A.; Kumar, P.; Chaturvedi, C.P.; Ecelbarger, C.M.; Godbole, M.M.; Tiwari, S. Greater efficacy of atorvastatin versus a non-statin lipid-lowering agent against renal injury: Potential role as a histone deacetylase inhibitor. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Z.; Jiang, H.; Wang, Z.; Qu, J. Atorvastatin partially inhibits the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in A549 cells induced by TGF-β1 by attenuating the upregulation of SphK1. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 36, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, I.; Stamatakis, K.; Oeste, C.L.; Pérez-Sala, D. Vimentin as a Multifaceted Player and Potential Therapeutic Target in Viral Infections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Dong, S.; Li, Z.; Guo, X.; Zhang, N.; Yu, B.; Sun, Y. Atorvastatin Calcium Inhibits PDGF-ββ-Induced Proliferation and Migration of VSMCs Through the G0/G1 Cell Cycle Arrest and Suppression of Activated PDGFRβ-PI3K-Akt Signaling Cascade. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 44, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo, M.; Raurell, I.; Barberá, A.; Hide, D.; Gil, M.; Estrella, F.; Salcedo, M.T.; Augustin, S.; Genescà, J.; Martell, M. Synergic effect of atorvastatin and ambrisentan on sinusoidal and hemodynamic alterations in a rat model of NASH. Dis. Model. Mech. 2021, 14, dmm048884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchant, V.; Trionfetti, F.; Tejedor-Santamaria, L.; Rayego-Mateos, S.; Rotili, D.; Bontempi, G.; Domenici, A.; Menè, P.; Mai, A.; Martín-Cleary, C.; et al. BET Protein Inhibitor JQ1 Ameliorates Experimental Peritoneal Damage by Inhibition of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Zhang, S.; Wang, L.; Huang, S.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Wang, P.; Zhou, L.; et al. BET protein inhibitor JQ1 downregulates chromatin accessibility and suppresses metastasis of gastric cancer via inactivating RUNX2/NID1 signaling. Oncogenesis 2020, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wu, X.; Wang, R.; Yang, C.; Li, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, F.; Yang, P. BRD4 inhibition suppresses cell growth, migration and invasion of salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma. Biol. Res. 2017, 50, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiago, M.; Capparelli, C.; Erkes, D.A.; Purwin, T.J.; Heilman, S.A.; Berger, A.C.; Davies, M.A.; Aplin, A.E. Targeting BRD/BET proteins inhibits adaptive kinome upregulation and enhances the effects of BRAF/MEK inhibitors in melanoma. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 122, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Masucci, M.V.; Zhou, X.; Liu, N.; Zang, X.; Tolbert, E.; Zhao, T.C.; Zhuang, S. Pharmacological targeting of BET proteins inhibits renal fibroblast activation and alleviates renal fibrosis. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 69291–69308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendler, C.C.; Schmoldt, A.; Flentke, G.R.; Case, L.C.; Quadro, L.; Blaner, W.S.; Lough, J.; Smith, S.M. Increased Fibronectin Deposition in Embryonic Hearts of Retinol-Binding Protein–Null Mice. Circ. Res. 2003, 92, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strouhalova, D.; Macejova, D.; Mosna, B.; Bobal, P.; Otevrel, J.; Lastovickova, M.; Brtko, J.; Bobalova, J. Down-regulation of vimentin by triorganotin isothiocyanates—Nuclear retinoid X receptor agonists: A proteomic approach. Toxicol. Lett. 2020, 318, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manku, G.; Wang, Y.; Merkbaoui, V.; Boisvert, A.; Ye, X.; Blonder, J.; Culty, M. Role of Retinoic Acid and Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor Cross Talk in the Regulation of Neonatal Gonocyte and Embryonal Carcinoma Cell Differentiation. Endocrinology 2015, 156, 346–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Primer Sequence | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Collagen 3α1 | Forward: 5′-TGATGGGATCCAATGAGGGAGA-3′ Reverse: 5′-GAGTCTCATGGCCTTGCGTGTTT-3′ | [27] |

| Step | Temperature | Time | No. of Cycles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reverse transcription | 45 °C | 25 min | 1 |

| RT inactivation/initial denaturation | 94 °C | 4 min | 1 |

| Amplification | 94 °C | 30 s | 40 |

| 57 °C | 30 s | ||

| 72 °C | 1–2 kb/min | ||

| Final extension | 72 °C | 7 min | 1 |

| Antibody | Cat. No | Company | Dilution | Clonality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vimentin | EPR3776 | Abcam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands | 1:1000 | r mAb |

| Fibronectin | AB1954 | Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany | 1:3000 | r pAb |

| GAPDH (6C5) | sc-32233 | Santa Cruz, Heidelberg, Germany | 1:1000 | m mAb |

| PDGFR-β (958) | sc-432 | Santa Cruz, Heidelberg, Germany | 1:1000 | r pAb |

| β-actin | A5441 | Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany | 1:10,000 | m mAb |

| goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L), HRP | 31460 | Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA | 1:5000 | g |

| goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L), HRP | 31430 | Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA | 1:5000 | g |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ezzat, A.A.; Tammam, S.N.; Weiskirchen, R.; Schröder-Lange, S.K.; Mansour, S. Targeted Liver Fibrosis Therapy: Evaluating Retinol-Modified Nanoparticles and Atorvastatin/JQ1-Loaded Nanoparticles for Deactivation of Activated Hepatic Stellate Cells. Livers 2025, 5, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers5040063

Ezzat AA, Tammam SN, Weiskirchen R, Schröder-Lange SK, Mansour S. Targeted Liver Fibrosis Therapy: Evaluating Retinol-Modified Nanoparticles and Atorvastatin/JQ1-Loaded Nanoparticles for Deactivation of Activated Hepatic Stellate Cells. Livers. 2025; 5(4):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers5040063

Chicago/Turabian StyleEzzat, Aya A., Salma N. Tammam, Ralf Weiskirchen, Sarah K. Schröder-Lange, and Samar Mansour. 2025. "Targeted Liver Fibrosis Therapy: Evaluating Retinol-Modified Nanoparticles and Atorvastatin/JQ1-Loaded Nanoparticles for Deactivation of Activated Hepatic Stellate Cells" Livers 5, no. 4: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers5040063

APA StyleEzzat, A. A., Tammam, S. N., Weiskirchen, R., Schröder-Lange, S. K., & Mansour, S. (2025). Targeted Liver Fibrosis Therapy: Evaluating Retinol-Modified Nanoparticles and Atorvastatin/JQ1-Loaded Nanoparticles for Deactivation of Activated Hepatic Stellate Cells. Livers, 5(4), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers5040063