Hepatitis C Virus Opportunistic Screening in South-Eastern Tuscany Residents Admitted to the University Hospital in Siena

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Study Design

- -

- Age: any patient born before 1 January 1969.

- -

- Hospitalisation status: any patient admitted to hospital, regardless of the specific cause leading to hospitalisation.

- -

- Willingness to provide free and informed consent.

- -

- Impossibility of providing free and voluntary informed consent,

- -

- Prior diagnosis of HCV.

2.2. Opportunistic Screening and Linkage to Care

2.3. Statistical Analysis

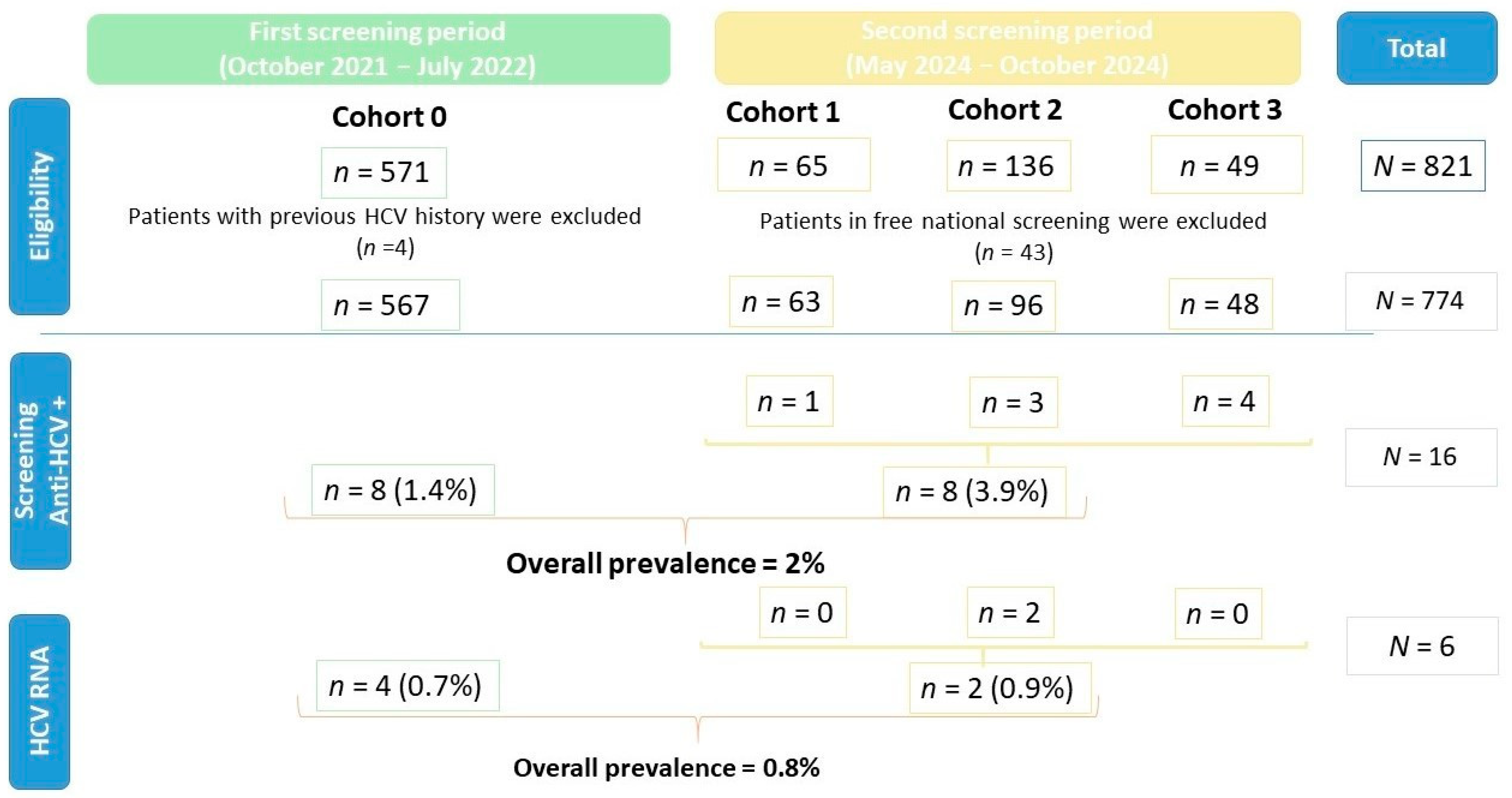

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. First Period of Screening

3.3. Second Period of Screening

3.4. Opportunistic Anti-HCV Screening

3.4.1. Cohort 0

3.4.2. Cohort 1

3.4.3. Cohort 2

3.4.4. Cohort 3

3.5. Molecular Diagnosis and Linkage to Care

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis 2016–2021. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/246177/1/WHO-HIV-2016.06-eng.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2016).

- Kim, H.N.; Corcorran, M.A. Treatment of HCV in Persons with HIV Coinfection. Available online: https://www.hepatitisc.uw.edu/go/key-populations-situations/treatment-hiv-coinfection/core-concept/all (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Polaris Observatory. The Authoritative Resource for Epidemiological Data, Modeling Tools, Training, and Decision Analytics to Support Global Elimination of Hepatitis B and C by 2030. Available online: http://www.hepbunited.org/assets/Webinar-Slides/8b54a78215/POLARIS-Brief-181217.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- World Health Organization. Hepatitis C. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-c (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Thomas, A.M.; Litwin, A.H.; Tsui, J.I.; Sprecht-Walsh, S.; Blalock, K.L.; Tashima, K.T.; Lum, P.J.; Feinberg, J.; Page, K.; Mehta, S.H.; et al. Retreatment of Hepatitis C Virus Among People Who Inject Drugs. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2025, ciaf082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falade-Nwulia, O.; Sulkowski, M.S.; Merkow, A.; Latkin, C.; Mehta, S.H. Understanding and addressing hepatitis C reinfection in the oral direct-acting antiviral era. J. Viral Hepat. 2018, 25, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasi, C.; Silvestri, C.; Voller, F. Update on Hepatitis C Epidemiology: Unaware and Untreated Infected Population Could Be the Key to Elimination. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2020, 2, 2808–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondili, L.A.; Andreoni, M.; Aghemo, A.; Mastroianni, C.M.; Merolla, R.; Gallinaro, V.; Craxì, A. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus estimates of undiagnosed individuals in different Italian regions: A mathematical modelling approach by route of transmission and fibrosis progression with results up to January 2021. New Microbiol. 2022, 45, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Andriulli, A.; Stroffolini, T.; Mariano, A.; Valvano, M.R.; Grattagliano, I.; Ippolito, A.M.; Grossi, A.; Brancaccio, G.; Coco, C.; Russello, M.; et al. Declining prevalence and increasing awareness of HCV infection in Italy: A population-based survey in five metropolitan areas. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 53, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministero della Salute. DECRETO 14 Maggio 2021. Esecuzione dello Screening Nazionale per L’eliminazione del Virus dell’HCV. (21A04075) (GU Serie Generale n.162 del 08-07-2021). Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2021/07/08/21A04075/sg (accessed on 8 July 2021).

- REGIONE TOSCANA. Avvio di un Programma di Screening Gratuito per Prevenire, Eliminare ed Eradicare il Virus Dell’epatite C, in Attuazione Dell’art. 25-Sexies del D.L.n. 162/2019. Available online: http://www301.regione.toscana.it/bancadati/atti/Contenuto.xml?id=5355950&nomeFile=Delibera_n.1538_del_27-12-2022 (accessed on 31 December 2022).

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C 2018. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 461–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco. Registri AIFA per il Monitoraggio dei Farmaci Anti-HCV. Last Update March 31. 2025. Available online: https://www.aifa.gov.it/aggiornamento-epatite-c (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J. Hepatol. 2025; In Press. [CrossRef]

- Stasi, C.; Silvestri, C.; Bravi, S.; Aquilini, D.; Casprini, P.; Epifani, C.; Voller, F.; Cipriani, F. Hepatitis B and C epidemiology in an urban cohort in Tuscany (Italy). Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2015, 39, e13–e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcellusi, A.; Mennini, F.S.; Andreoni, M.; Kondili, L.A.; PITER Collaboration Study Group. Screening strategy to advance HCV elimination in Italy: A cost-consequence analysis. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2024, 25, 1261–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasi, C.; Milli, C.; Voller, F.; Silvestri, C. The Epidemiology of Chronic Hepatitis C: Where We Are Now. Livers 2024, 4, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istat. Il Censimento permanente della popolazione in Toscana. Available online: https://www.istat.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Toscana_Focus2022.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Puglia, M.; Stasi, C.; Da Frè, M.; Voller, F. Prevalence and characteristics of HIV/HBV and HIV/HCV coinfections in Tuscany. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 20, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasi, C.; Silvestri, C.; Fanti, E.; Di Fiandra, T.; Voller, F. Prevalence and features of chronic viral hepatitis and HIV coinfection in Italian prisons. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2016, 34, e21–e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stasi, C.; Monnini, M.; Cellesi, V.; Salvadori, M.; Marri, D.; Ameglio, M.; Gabbuti, A.; Di Fiandra, T.; Voller, F.; Silvestri, C. Screening for hepatitis B virus and accelerated vaccination schedule in prison: A pilot multicenter study. Vaccine 2019, 37, 1412–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvestri, C.; Stasi, C.; Lazzeretti, M.; Voller, F. Substance Abuse Disorder and Viral Infections (Hepatitis, HIV): A Multicenter Study in Tuscan Prisons. J. Correct. Health Care 2021, 27, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monti, M.; Caruso, T.; Castellaccio, A.; De Giorgi, I.; Cavallini, G.; Manca, M.L.; Lorini, S.; Marri, S.; Petraccia, L.; Madia, F.; et al. HBV and HCV testing outcomes among marginalized communities in Italy, 2019-2024: A prospective study. The Lancet regional health. Europe 2024, 49, 101172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad, A.; McGeer, R.; Gray, E.; Bibby-Jones, A.M.; Gage, H.; Salvaggio, L.; Charles, V.; Sanderson, N.; O’Sullivan, M.; Bird, T.; et al. A novel multisite model to facilitate hepatitis C virus elimination in people experiencing homelessness. JHEP Rep. 2024, 6, 101183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degenhardt, L.; Peacock, A.; Colledge, S.; Leung, J.; Grebely, J.; Vickerman, P.; Stone, J.; Cunningham, E.B.; Trickey, A.; Dumchev, K.; et al. Global prevalence of injecting drug use and sociodemographic characteristics and prevalence of HIV, HBV, and HCV in people who inject drugs: A multistage systematic review. The Lancet. Glob. Health 2017, 5, e1192–e1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busschots, D.; Kremer, C.; Bielen, R.; Koc, Ö.M.; Heyens, L.; Nevens, F.; Hens, N.; Robaeys, G. Hepatitis C prevalence in incarcerated settings between 2013-2021: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gower, E.; Estes, C.; Blach, S.; Razavi-Shearer, K.; Razavi, H. Global epidemiology and genotype distribution of the hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 2014, 61 (Suppl. 1), S45–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, C.; Bartolacci, S.; Pepe, P.; Monnini, M.; Voller, F.; Cipriani, F.; Stasi, C. Attempt to calculate the prevalence and features of chronic hepatitis C infection in Tuscany using administrative data. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 9829–9835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, Y.R.; Jagdish, R.; Leith, D.; Kim, J.U.; Yoshida, K.; Majid, A.; Ge, Y.; Ndow, G.; Shimakawa, Y.; Lemoine, M. Prevalence of occult hepatitis B virus infection in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 932–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccalini, S.; Zanella, B.; Del Riccio, M.; Bonito, B.; Biamonte, M.A.; Bruschi, M.; Ionita, G.; Paolini, D.; Innocenti, M.; Baggiani, L.; et al. Impact of the Hepatitis B Immunization Strategy Adopted in Italy from 1991: The Results of a Seroprevalence Study on the Adult Population of Florence, Italy. Pathogens 2025, 14, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasi, C.; Tiengo, G.; Sadalla, S.; Zignego, A.L. Treatment or Prophylaxis against Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Patients with Rheumatic Disease Undergoing Immunosuppressive Therapy: An Update. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Garcia, O.A.; Zelyas, N.; Meier-Stephenson, V.; Halloran, K.; Doucette, K. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in hepatitis B core antibody positive lung transplant recipients. JHLT Open 2023, 3, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, S.K.; Arita, J.; Akamatsu, N.; Ichida, A.; Nishioka, Y.; Miyata, A.; Kawahara, T.; Inagaki, Y.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Kaneko, J.; et al. Prediction of intrahepatic covalently closed circular DNA levels in patients with resolved hepatitis B virus infection: Impact of serum antibody to hepatitis B core antigen titers. Hepatol. Res. 2025, 55, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Overall Population (Second Screening Period) | Cohort 1 | Cohort 2 | Cohort 3 | |

| Patients, n | 207 | 63 | 96 | 48 |

| Demography | ||||

| Age, y | 77.4 ± 8.5 | 78.5 ± 8.9 | 75.3 ± 10.3 | 80.4 ± 12.0 |

| Female, n (%) | 98 (47.3) | 30 (47.6) | 40 (41.7) | 28 (58.3) |

| Residence | ||||

| Italy, n (%) | 202 (97.6) | 62 (98.4) | 92 (96.0) | 48 (100) |

| Tuscany, n (%) | 191 (92.3) | 61 (96.8) | 83 (86.5) | 47 (97.9) |

| Siena, n (%) | 169 (81.6) | 60 (95.3) | 66 (68.7) | 43 (89.5) |

| Foreign origin, n (%) | 13 (6.2) | - | 10 (10.42) | 3 (6.25) |

| Medical history | ||||

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 183 (88.4) | 60 (95.2) | 86 (89.5) | 37 (77.1) |

| Cardiovascular diseases, n (%) | 141 (68.1) | 50 (79.3) | 65 (67.7) | 26 (54.2) |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 48 (23.2) | 20 (31.7) | 7 (7.3) | 21 (43.8) |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 25 (12.1) | 3 (4.7) | 10 (10.4) | 12 (25.0) |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 37 (17.9) | 14 (22.2) | 14 (14.6) | 9 (18.8) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 46 (22.2) | 10 (15.8) | 26 (27.1) | 10 (20.8) |

| COPD, n (%) | 31 (15.0) | 12 (19) | 11 (11.5) | 8 (16.6) |

| Liver and Hepatobiliary diseases, n (%) | 58 (28.0) | 2 (3.2) | 38 (39.5) | 18 (37.5) |

| Liver cirrhosis, n (%) | 24 (11.6) | - | 6 (6.2) | 18 (37.5) |

| Hepatobiliary, n (%) | 28 (13.53) | 1 (1.6) | 27 (28.1) | - |

| Cancer, n (%) | 73 (35.3) | 21 (33.3) | 33 (34.4) | 19 (39.6) |

| Hepatobiliary, n (%) | - | - | 7 (7.3) | - |

| HCC, n (%) | 2 (1.0) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (1.0) | - |

| Immune-mediated diseases, n (%) | 19 (9.2) | 5 (7.9) | 12 (12.5) | 2 (4.1) |

| IBD, n (%) | 6 (2.9) | - | 6 (6.5) | - |

| Rheumatoid arthritis, n (%) | 3 (1.4) | 1 (1.6) | 2 (2) | - |

| Ankylosing spondylitis, n (%) | 2 (0.9) | 2 (2) | ||

| Vasculitis, n (%) | 2(0.9) | 1 (1.6) | - | 1 (2) |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus, n (%) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1.6) | - | - |

| Common variable immunodeficiency, n (%) | - | - | 1 (2) | |

| Therapy | ||||

| Immuno-modulating drugs, n (%) | 32 (15.5) | 10 (15.8) | 14 (14.6) | 8 (16.6) |

| Glucocorticoids, n (%) | 27 (13.0) | 8 (12.6) | 13 (13.5) | 6 (12.5) |

| Mean daily dose *, mg | 24.5 | 19.2 | 17.0 | 37.3 |

| Biologic drugs, n (%) | 6 (2.9) | 2 (3.2) | 1 (1.0) | 3 (6.3) |

| Other immunosuppressants, n (%) | 2 (1.0) | - | 2 (2) | - |

| Laboratory data | ||||

| Transaminase elevation, n (%) | 63 (30.4) | 10 (15.9) | 46 (48.0) | 7 (14.6) |

| AST levels, IU/L (median, IQR) | 21 (38.5–15) | 20 (29–14) | 26 (65−17) | 19 (31.7–14) |

| ALT levels, IU/L (median, IQR) | 18 (41–11) | 16 (24–11) | 29 (86.5–13) | 17 (27–11) |

| Overall Population | Cohort 1 | Cohort 2 | Cohort 3 | |

| HCV infection, n (%) | 8 (3.9) | 1(1.6) | 3 (3.1) | 4 (8.3) |

| HCV antibody-positive, n (%) | 8 (3.9) | 1(1.6) | 3 (3.1) | 4 (8.3) |

| Age, y | 73.3 ± 10.7 | 88 | 65.6 ± 9.0 | 75.3 ± 10.4 |

| Female, n (%) | 5 (2.4) | - | 1 (1) | 4 (8.3) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 8 (3.9) | 1 (1.6) | 3 (3.1) | 4 (8.3) |

| Transaminasis elevation, n (%) | 2 (0.9) | 0 | 2 (2.1) | 0 |

| AST levels, IU/L | 22 (75.7–15.7) | 5 | 70 (93–16) | 22 (23–15) |

| ALT levels, IU/L | 16 (41–10) | 10 | 41 (71–16) | 14 (36–7) |

| HCV RNA-positive, n (%) | 2 (0.9) | 0 | 2 (2.1) | 0 |

| Age, y | 76 | - | 76 | - |

| Female, n (%) | 1 (0.5) | - | 1 (1) | - |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 2 (0.9) | - | 2 (2.1) | - |

| Therapy, n (%) | 1 (0.5) DAA | - | 1 (1) DAA | - |

| Transaminasis elevation, n (%) | 0 | - | 0 | - |

| AST levels, IU/L | 22 and 16 | - | 22 and 16 | - |

| ALT levels, IU/L | 36 and 16 | - | 36 and 16 | - |

| HBV markers, n (%) | 9 (9.4) | - | 9 (9.4) | - |

| Age, y | 80.0 ± 4.9 | - | 80.0 ± 4.9 | - |

| Female, n (%) | 3 (3.1) | - | 3 (3.1) | - |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 9 (9.4) | - | 9 (9.4) | - |

| Therapy | - | - | - | - |

| Transaminase elevation, n (%) | 3 (3.1) | - | 3 (3.1) | - |

| AST levels, IU/L(median, IQR) | 24 (63.5–18.5) | - | 24 (63.5–18.5) | - |

| ALT levels, IU/L(median, IQR) | 25 (56–13.5) | - | 25 (56–13.5) | - |

| HBsAg+ | 1 (1) | - | 1 (1) | - |

| Anti-HBc+ | 4 (4.2) | - | 4 (4.2) | - |

| Anti-HBc+ and anti-HBs+ | 4 (4.2) | - | 4 (4.2) | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stasi, C.; Marzotti, T.; Nassi, F.; Giugliano, G.; Pacini, S.; Rentini, S.; Accioli, R.; Macchiarelli, R.; Gennari, L.; Lazzerini, P.E.; et al. Hepatitis C Virus Opportunistic Screening in South-Eastern Tuscany Residents Admitted to the University Hospital in Siena. Livers 2025, 5, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers5030030

Stasi C, Marzotti T, Nassi F, Giugliano G, Pacini S, Rentini S, Accioli R, Macchiarelli R, Gennari L, Lazzerini PE, et al. Hepatitis C Virus Opportunistic Screening in South-Eastern Tuscany Residents Admitted to the University Hospital in Siena. Livers. 2025; 5(3):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers5030030

Chicago/Turabian StyleStasi, Cristina, Tommaso Marzotti, Filippo Nassi, Giovanna Giugliano, Sabrina Pacini, Silvia Rentini, Riccardo Accioli, Raffaele Macchiarelli, Luigi Gennari, Pietro Enea Lazzerini, and et al. 2025. "Hepatitis C Virus Opportunistic Screening in South-Eastern Tuscany Residents Admitted to the University Hospital in Siena" Livers 5, no. 3: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers5030030

APA StyleStasi, C., Marzotti, T., Nassi, F., Giugliano, G., Pacini, S., Rentini, S., Accioli, R., Macchiarelli, R., Gennari, L., Lazzerini, P. E., & Brillanti, S., on behalf of Le Scotte HCV Screening Group. (2025). Hepatitis C Virus Opportunistic Screening in South-Eastern Tuscany Residents Admitted to the University Hospital in Siena. Livers, 5(3), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers5030030