Development of Importance Measures Reflecting the Risk Triplet in Dynamic Probabilistic Risk Assessment: The Concept and Measures of Risk Importance †

Abstract

1. Introduction

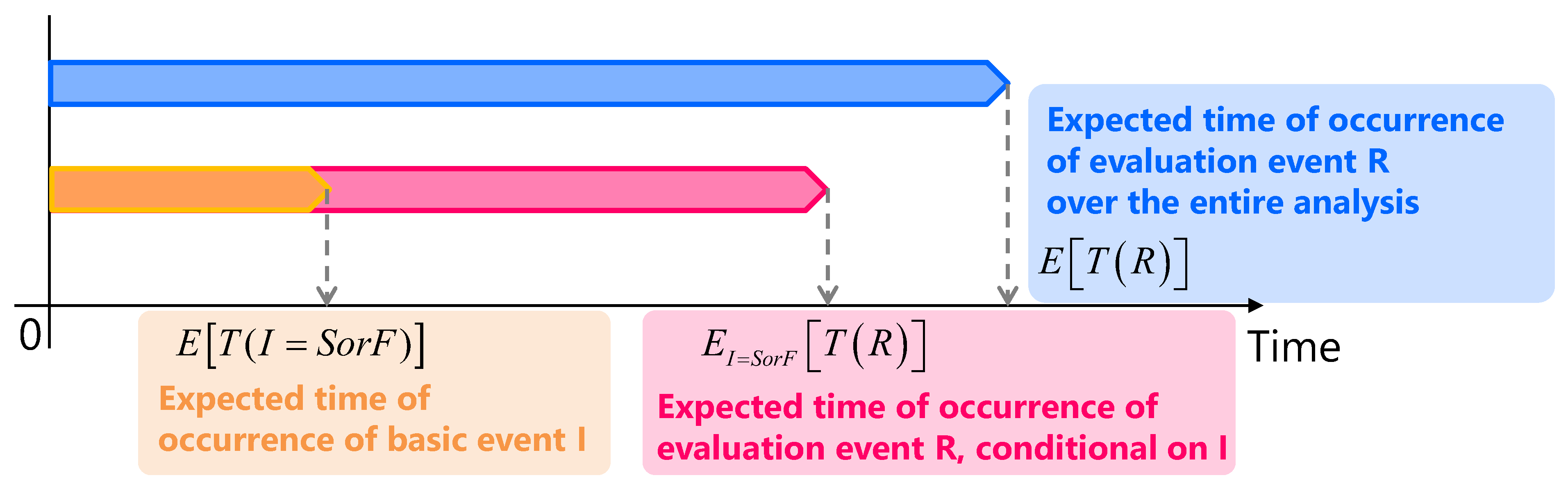

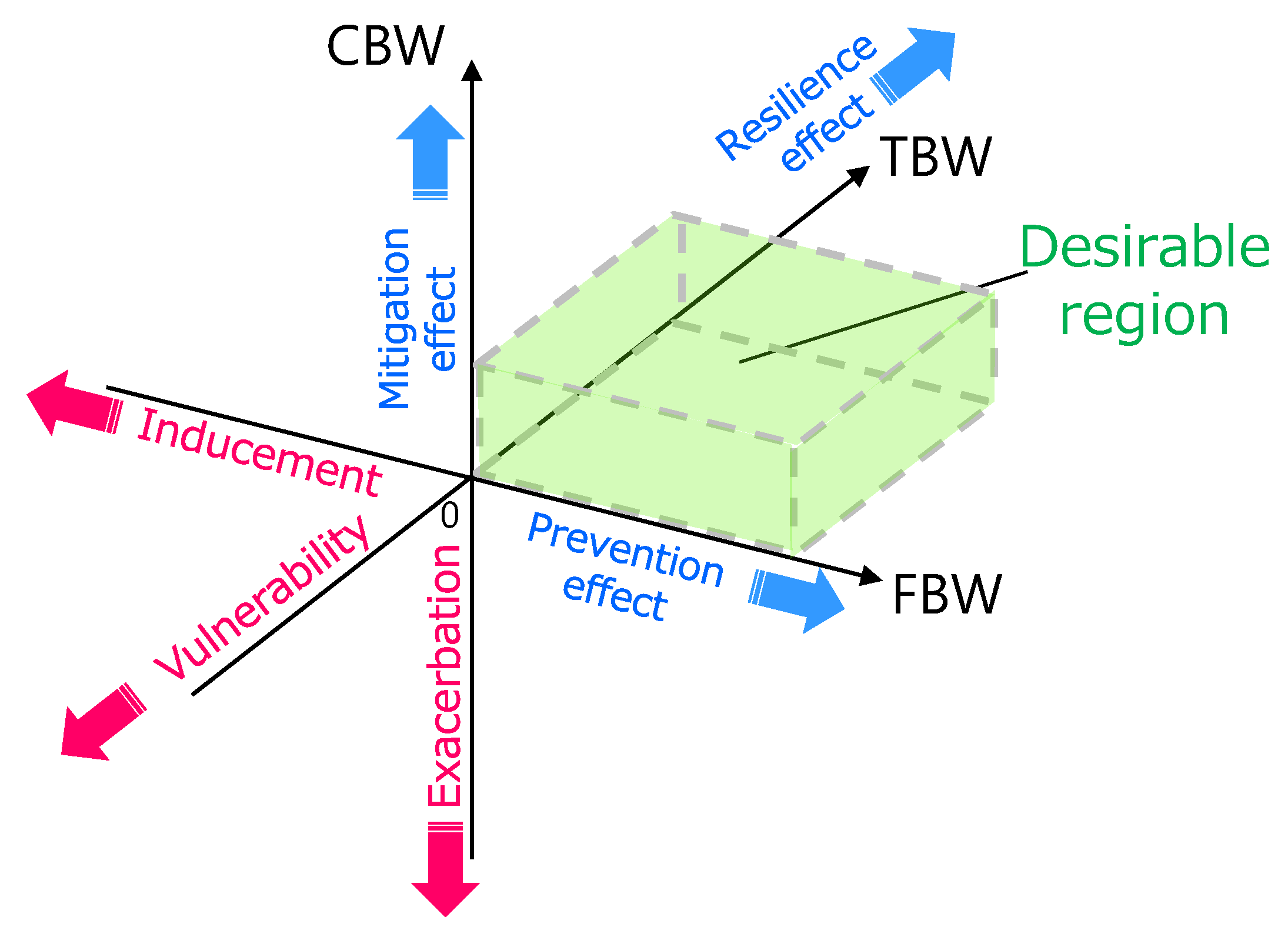

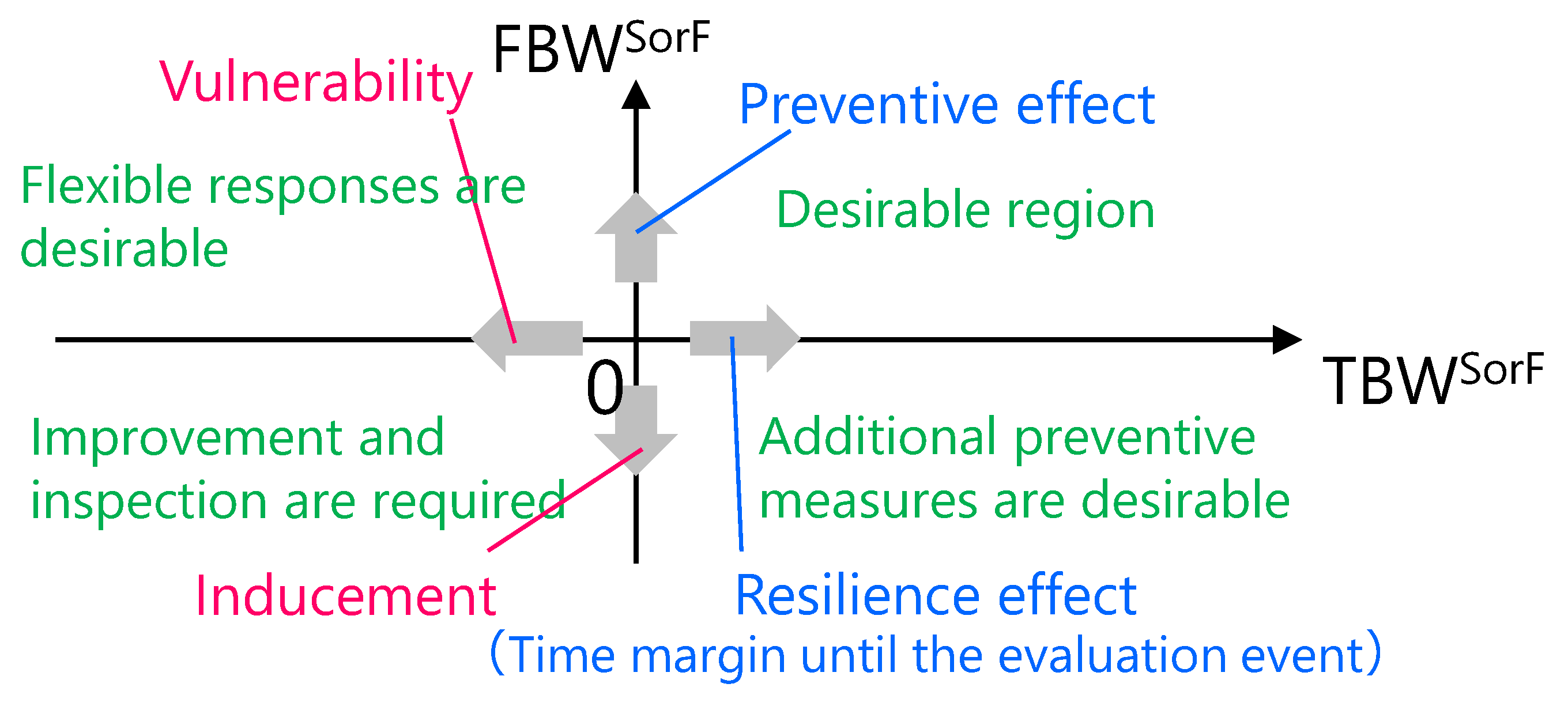

2. RIMs Reflecting the Risk Triplet

- TBW

- 2.

- FBW

- 3.

- CBW

3. Application to Dynamic PRA

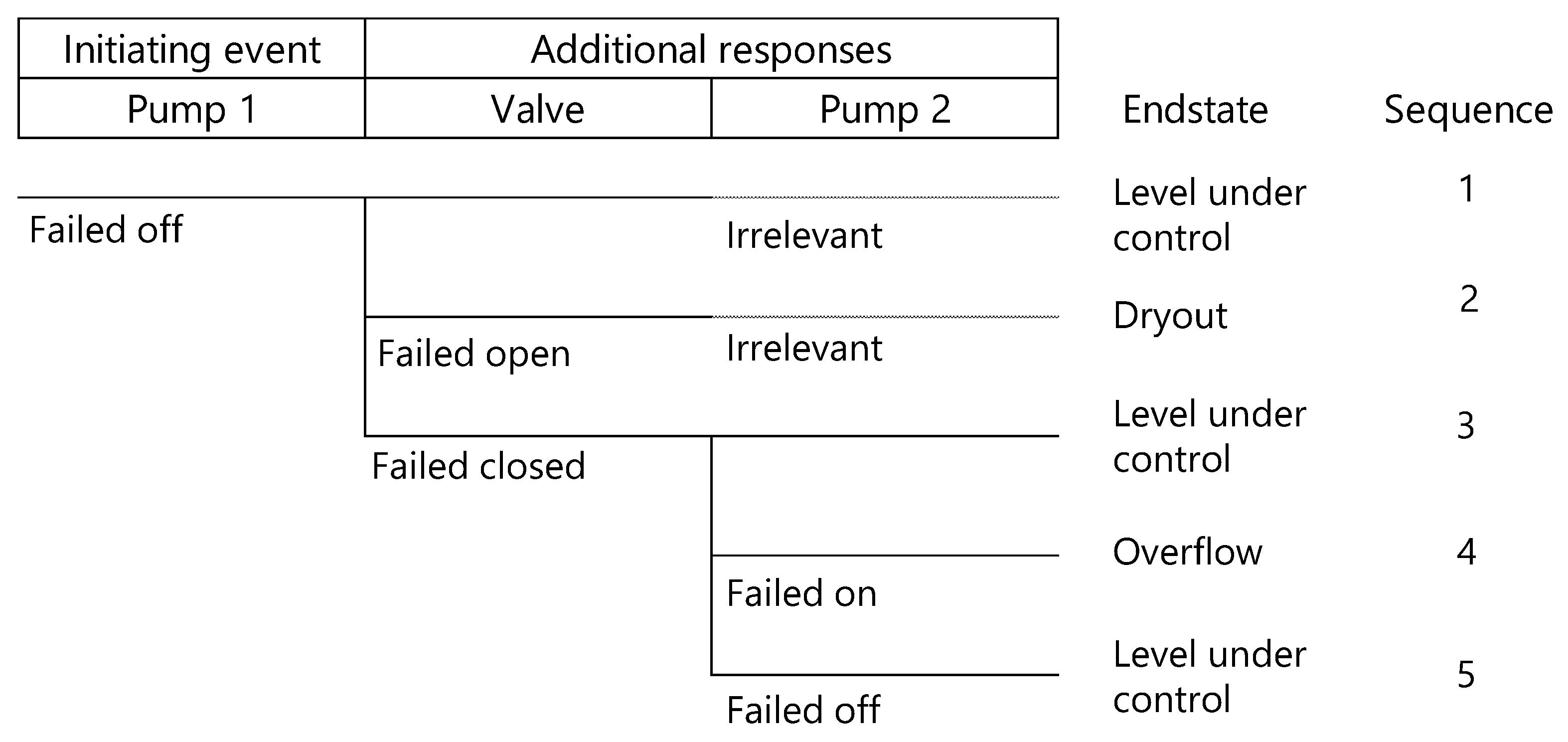

3.1. Holdup Tank Problem

3.2. PRA Methods

3.2.1. Static PRA Method

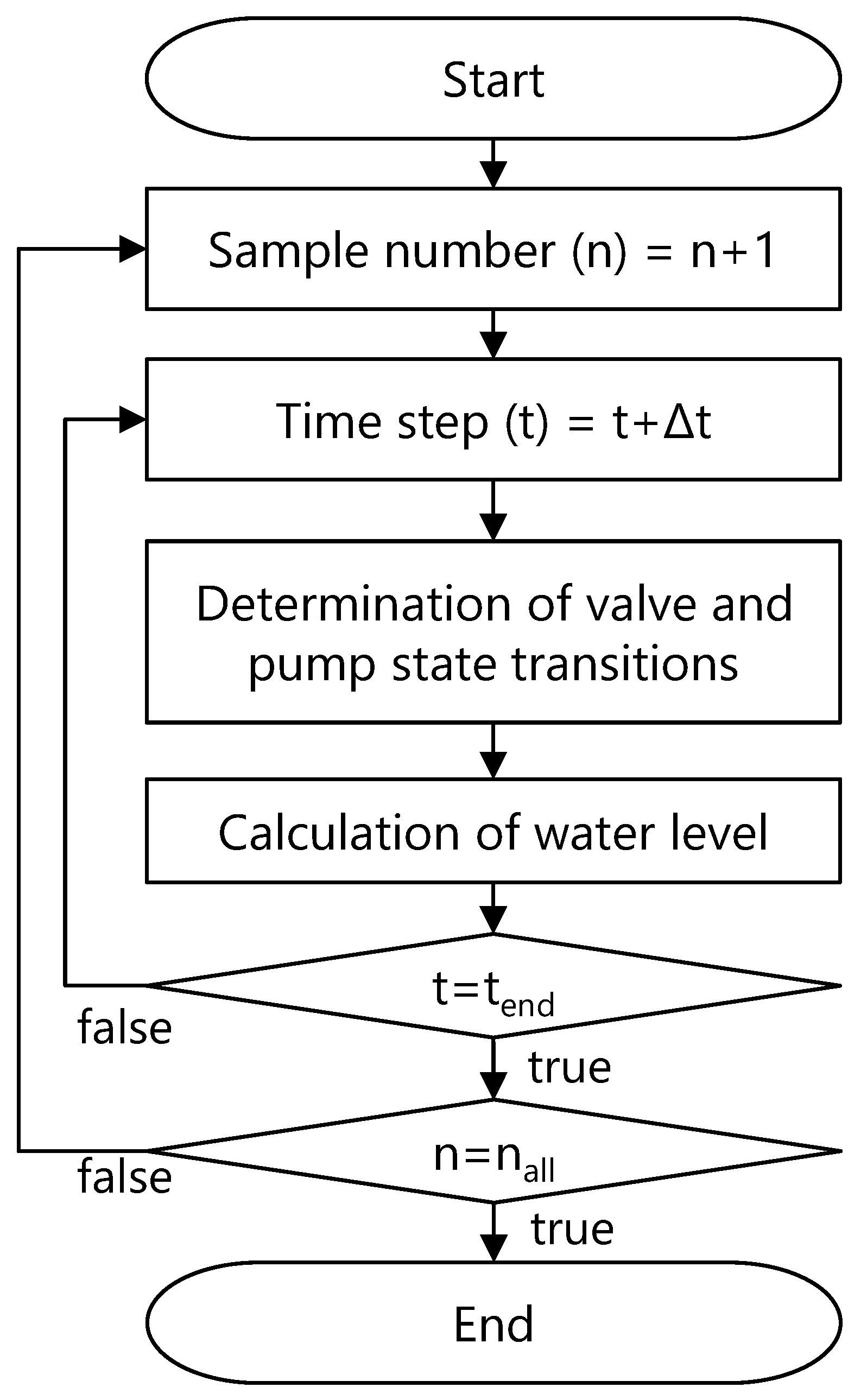

3.2.2. Dynamic PRA Method

3.3. Results and Discussion

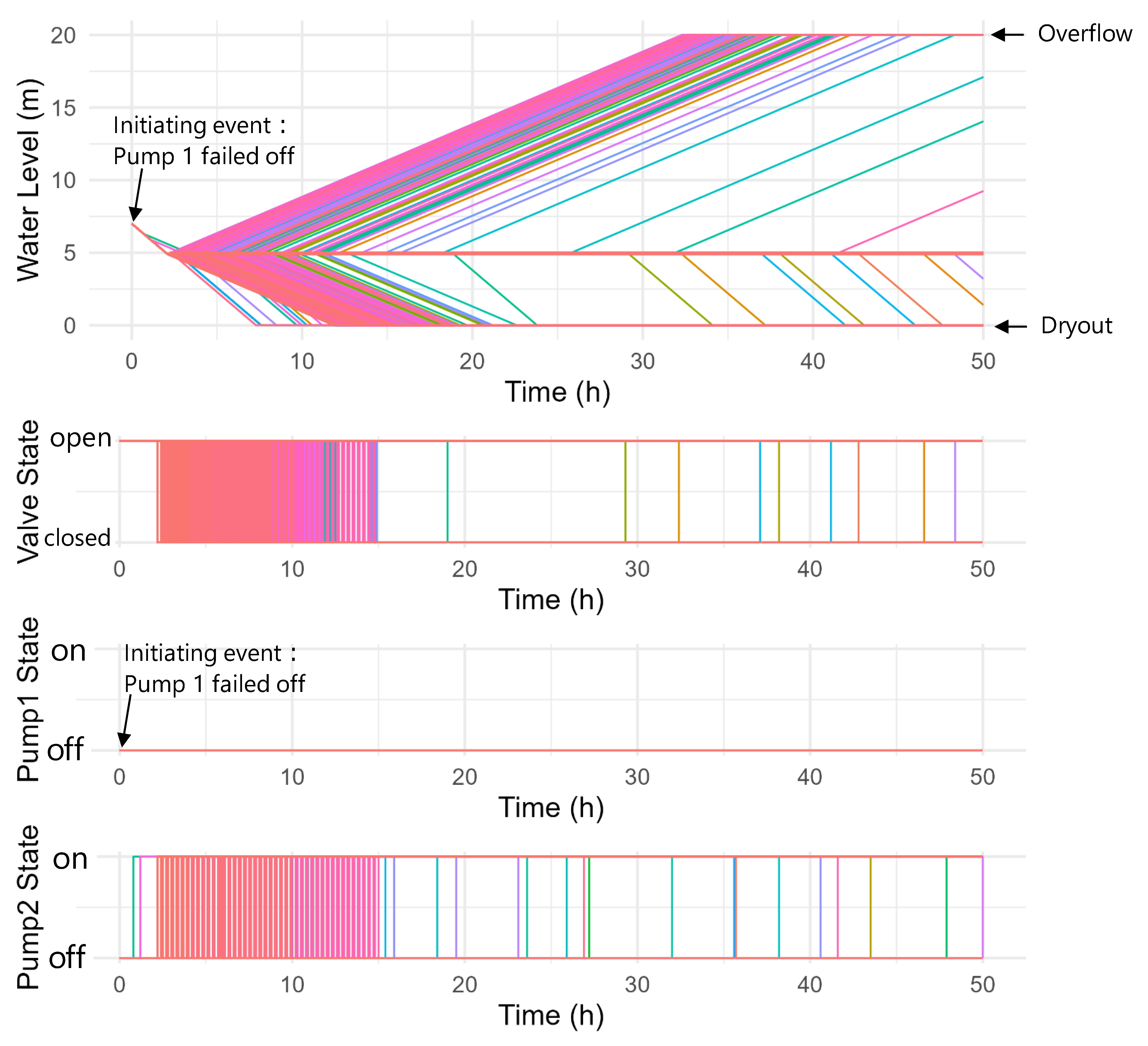

3.3.1. Time Evolution of Water Level and Components Status

3.3.2. Comparison of Existing RIMs with Static PRA

3.3.3. Measurement of Risk Importance Reflecting the Risk Triplet

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AM | Accident Management |

| CBW | Consequence-Based Worth |

| CDF | Core Damage Frequency |

| CMMC | Continuous Markov chain Monte Carlo |

| DET | Dynamic Event Tree |

| DIM | Dynamic Importance Measure |

| ET | Event Tree |

| FBW | Frequency-Based Worth |

| FT | Fault Tree |

| FV | Fussell-Vesely |

| PRA | Probabilistic Risk Assessment |

| RAW | Risk Achievement Worth |

| RIDM | Risk-Informed Decision Making |

| RIM | Risk Importance Measure |

| RRW | Risk Reduction Worth |

| SSC | Structures, Systems, and Component |

| TBW | Timing-Based Worth |

References

- U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Reactor Safety Study: An Assessment of Accident Risks in U.S. Commercial Nuclear Power Plants; Main Report; WASH-1400 (NUREG 75/014); U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 1975.

- U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Severe Accident Risk: An Assessment for Five U.S. Nuclear Power Plants; NUREG-1150; U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 1991.

- U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. State-of-the-Art Reactor Consequence Analyses (SOARCA) Report: Part 1 and 2; NUREG-1935; U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- Nuclear Energy Agency. Use and Development of Probabilistic Safety Assessments at Nuclear Facilities; NEA/CSNI/R(2019)10; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Use of Probabilistic Risk Assessment Methods in Nuclear Regulatory Activities; Final Policy Statement. Fed. Regist. 1995, 60, 42622–42629. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. An Approach for Using Probabilistic Risk Assessment in Risk-Informed Decisions on Plant-Specific Changes to the Licensing Basis; Regulatory Guide 1.174, Revision 3; U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Regulatory Analysis Guidelines of the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission; NUREG/BR-0058, Revision 5; U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 2017.

- Zio, E. Risk Importance Measures. In Safety and Risk Modeling and Its Applications; Pham, H., Ed.; Springer: London, UK, 2011; pp. 151–196. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Code of Federal Regulations, Title 10, Part 50, Section 50.69. Risk-Informed Categorization and Treatment of Structures, Systems and Components for Nuclear Power Reactors. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-10/chapter-I/part-50/subject-group-ECFR2f76ac8b7f9e21e/section-50.69 (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Nuclear Energy Institute. 10 CFR 50.69 SSC Categorization Guideline; NEI 00-04 (Rev. 0); Nuclear Energy Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nuclear Safety Commission. Regulatory Guide for Reviewing Classification of Importance of Safety Functions of Light Water Nuclear Power Reactor Facilities; Nuclear Safety Commission: Tokyo, Japan, 1990; revised 2009. (In Japanese)

- JEAG4611-2021; Guide on Designing Instrumentation and Control Systems of Safety Functions and Functions for Coping with Severe Accidents. Japan Electric Association: Tokyo, Japan, 2021.

- JEAG4612-2021; Guide on Classifying the Importance of Electrical and Mechanical Equipments of Safety Functions and Functions for Coping with Severe Accidents. Japan Electric Association: Tokyo, Japan, 2021.

- Siu, N. Technical Opinion Paper Dynamic PRA for Nuclear Power Plants: Not if But When? Draft for Comment; U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Aldemir, T. A Survey of Dynamic Methodologies for Probabilistic Safety Assessment of Nuclear Power Plants. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2013, 52, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusunoki, T.; Takaki, T.; Nakamura, A. A Review of Studies on Dynamic Probabilistic Risk Assessment. INSS J. 2019, 26, 262–273. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.; Tamaki, H.; Sugiyama, T.; Maruyama, Y. Dynamic Probabilistic Risk Assessment of Nuclear Power Plants Using Multi-Fidelity Simulations. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 223, 108503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.; Garrick, B.J. On the Quantitative Definition of Risk. Risk Anal. 1981, 1, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The words of risk analysis. Risk Anal. 1997, 17, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, J.M.; Mekendez, E.; Devooght, J. Relationship between Probabilistic Dynamics and Event Trees. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 1996, 52, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloos, M.; Peschke, J. MCDET—A Probabilistic Dynamics Method Combining Monte Carlo Simulation with the Discrete Dynamic Event Tree Approach. Nucl. Sci. Eng. 2004, 153, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloos, M.; Berner, N.; Peschke, J.; Scheuer, J. MCDET: A Tool for Integrated Deterministic Probabilistic Safety Analyses. In Advanced Concepts in Nuclear Energy Risk Assessment and Management; World Scientific Publishing: Singapore, 2018; pp. 87–131. [Google Scholar]

- Takata, T.; Azuma, E. Event Sequence Assessment of Deep Snow in Sodium-Cooled Fast Reactor Based on Continuous Markov Chain Monte Carlo Method with Plant Dynamics Analysis. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 1749–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinzaki, S.; Yamaguchi, A.; Takata, T. Quantification of Severe Accident Scenarios in Level 2 PSA of Nuclear Power Plant with Continuous Markov Chain Model and Monte Carlo Method. In Proceedings of the 10th Probabilistic Safety Assessment and Management & Asian Symposium on Risk Assessment and Management (PSAM 10), Seattle, WA, USA, 7–11 June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shinzaki, S.; Takata, T.; Yamaguchi, A. Dynamic Scenario Quantification Based on Continuous Markov Monte Carlo Method with Meta-Model of Thermal Hydraulics for Level 2 PSA. In Proceedings of the 14th International Topical Meeting on Nuclear Reactor Thermal Hydraulics (NURETH-14), Toronto, ON, Canada, 25–30 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mandelli, D.; Ma, Z.; Parisi, C.; Alfonsi, A.; Smith, C. Measuring Risk-Importance in a Dynamic PRA Framework. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2019, 128, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovsky, Z.K.; Denman, M.R.; Aldemir, T. Dynamic Importance Measures in the ADAPT Framework; SAND2016-5641C; Sandia National Laboratories: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Homma, T. A New Importance Measure for Sensitivity Analysis. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2010, 47, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.U.A.; Kim, J.; Aldemir, T.; Kang, H.G. Importance Measure for Dynamic Probabilistic Risk Assessment and Cost Savings for Safety Systems and Components. In Proceedings of the 18th International Probabilistic Safety Assessment and Analysis (PSA 2023), Knoxville, TN, USA, 15–20 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.; Tamaki, H.; Sibamoto, Y.; Maruyama, Y.; Takada, T.; Narukawa, T.; Takata, T. Development of Importance Measures Reflecting the Risk Triplet in Dynamic Probabilistic Risk Assessment: A Case Study Using MELCOR and RAPID. J. Nucl. Eng. 2025, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narukawa, T.; Takata, T.; Zheng, X.; Tamaki, H.; Sibamoto, Y.; Maruyama, Y.; Takada, T. Development of Risk Importance Measures for Dynamic PRA Based on Risk Triplet (1): The Concept and Measures of Risk Importance. In Proceedings of the Probabilistic Safety Assessment and Management & Asian Symposium on Risk Assessment and Management (PSAM 17 & ASRAM 2024), Sendai, Miyagi, Japan, 7–11 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Siu, N. Risk Assessment for Dynamic Systems: An Overview. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 1994, 43, 43–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Water Level (x) | Valve | Pump 1 | Pump 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open | On | Off | |

| Open | Off | Off | |

| Closed | On | On |

| Component | Flow Rate (m3/h) | Failure Mode | Failure Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Valve | 1.0 | Demand failure (open/closed) | 0.05 (/demand) |

| Operational failure (open/closed) | 0.001 (/h) | ||

| Pump 1 | 1.0 | Demand failure (on/off) | 0.05 (/demand) |

| Operational failure (on/off) | 0.001 (/h) | ||

| Pump 2 | 0.5 | Demand failure (on/off) | 0.05 (/demand) |

| Operational failure (on/off) | 0.001 (/h) |

| Item | Set Value |

|---|---|

| (h) | 0.1 |

| (h) | 50 |

| (-) | 10,000 |

| Evaluation Event | Basic Event | FV | RAW | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static | Dynamic | Static | Dynamic | ||

| Overflow | Valve demand failure | 0.49 | 0.99 * | 10.38 * | 1.35 |

| Valve operational failure | 0.51 * | −0.01 | 10.37 | 0.10 | |

| Pump 2 demand failure | 0.49 | 0.91 | 10.38 * | 1.87 * | |

| Pump 2 operational failure | 0.51 * | 0.02 | 10.37 | 1.67 | |

| Dryout | Valve demand failure | 0.49 | 0.88 * | 10.38 * | 1.31 |

| Valve operational failure | 0.51 * | 0.02 | 10.37 | 2.03 * | |

| Pump 2 demand failure | 0.00 | −0.30 | 1.00 | 0.70 | |

| Pump 2 operational failure | 0.00 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 1.23 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Narukawa, T.; Takata, T.; Zheng, X.; Tamaki, H.; Sibamoto, Y.; Maruyama, Y.; Takada, T. Development of Importance Measures Reflecting the Risk Triplet in Dynamic Probabilistic Risk Assessment: The Concept and Measures of Risk Importance. J. Nucl. Eng. 2025, 6, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/jne6040049

Narukawa T, Takata T, Zheng X, Tamaki H, Sibamoto Y, Maruyama Y, Takada T. Development of Importance Measures Reflecting the Risk Triplet in Dynamic Probabilistic Risk Assessment: The Concept and Measures of Risk Importance. Journal of Nuclear Engineering. 2025; 6(4):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/jne6040049

Chicago/Turabian StyleNarukawa, Takafumi, Takashi Takata, Xiaoyu Zheng, Hitoshi Tamaki, Yasuteru Sibamoto, Yu Maruyama, and Tsuyoshi Takada. 2025. "Development of Importance Measures Reflecting the Risk Triplet in Dynamic Probabilistic Risk Assessment: The Concept and Measures of Risk Importance" Journal of Nuclear Engineering 6, no. 4: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/jne6040049

APA StyleNarukawa, T., Takata, T., Zheng, X., Tamaki, H., Sibamoto, Y., Maruyama, Y., & Takada, T. (2025). Development of Importance Measures Reflecting the Risk Triplet in Dynamic Probabilistic Risk Assessment: The Concept and Measures of Risk Importance. Journal of Nuclear Engineering, 6(4), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/jne6040049