Psychosocial Risk Factors for Complicated Perinatal Grief in Adult Women with Pregnancy Loss: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

Risk Factors for Complicated Grief

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Selection Criteria

4.2. Search Strategy

4.3. Study Selection

4.4. Identification of Studies

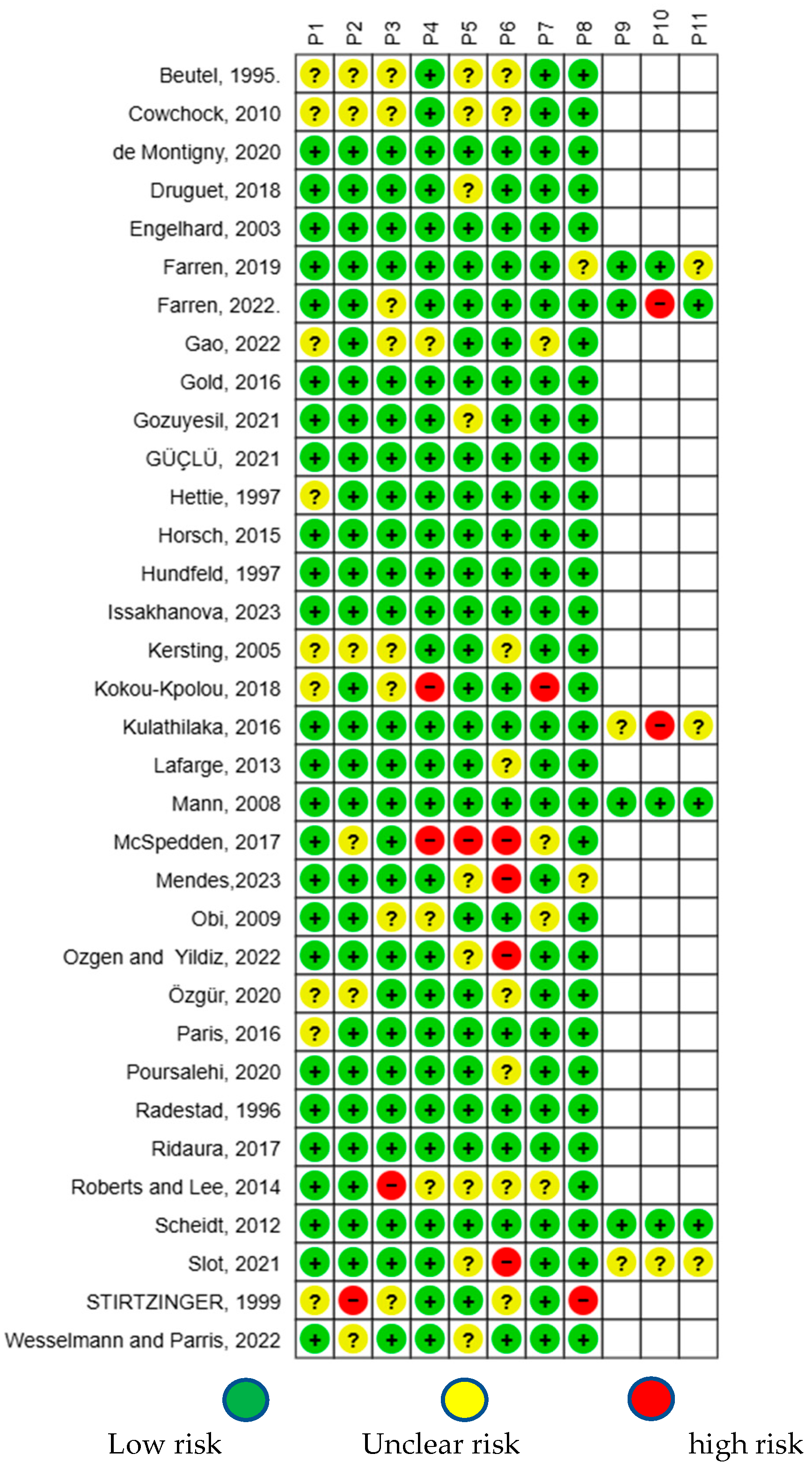

4.5. Risk of Bias Evaluation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, V.Y. Global. regional and national perinatal and neonatal mortality. J. Perinat. Med. 2003, 31, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, E.; Claudia, V.; Hoyert, D.; Martin, J. Change in the Primary Measure of Perinatal Mortality for Vital Statistics. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 2025, 74, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Auditoría y Revisión de Los Casos de Mortinatos y Muertes Neonatales: Hacer Que Cada Bebé Cuente. 2016. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241511223 (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Muncey, W.; Scott, M.; Lathi, R.B.; Eisenberg, M.L. The paternal role in pregnancy loss. Andrology 2025, 13, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.; Byatt, N. Infertility and perinatal loss: When the bough breaks. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2016, 18, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassaday, T.M. Impact of Pregnancy Loss on Psychological Functioning and Grief Outcomes. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 45, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, A.; Fleiszer, A.; Duhamel, F.; Sword, W.; Gilbert, K.R.; Corsini-Munt, S. Perinatal loss and perinatal grief: The challenge of ambiguity and disenfranchised grief. Omega 2011, 63, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mota, G.C.; Calleja, N.; Bravo, C.S.; Meléndez, J.C.; Buendía, J.B. Resiliencia y apoyo social como predictores del duelo perinatal en mujeres mexicanas: Modelo explicativo. Rev. Iberoam. Diagn. Eval.-E Aval. Psicol. 2021, 1, 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, M.; Yuan, M.; Zeng, T.; Wu, M. Complicated grief following the perinatal loss: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassidy, P.R. La privación de derechos en el duelo perinatal: Cómo el silencio, el silenciamiento y la autocensura complican el duelo (un estudio de métodos mixtos). OMEGA—J. Death Dying 2021, 88, 709–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, S.N. The Trauma of Perinatal Loss: A Scoping Review. Trauma Care 2022, 2, 392–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obst, K.L.; Due, C.; Oxlad, M.; Middleton, P. Men’s grief following pregnancy loss and neonatal loss: a systematic review and emerging theoretical model. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Demontigny, F.; Verdon, C.; Meunier, S.; Gervais, C.; Coté, I. Protective and risk factors for women’s mental health after a spontaneous abortion. Rev. Lat.-Am. Enferm. 2020, 28, e3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, K.J.; Leon, I.; Boggs, M.E.; Sen, A. Depression and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms After Perinatal Loss in a Population-Based Sample. J. Women’s Health 2016, 25, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obi, S.N.; Onah, H.E.; Okafor, I.I. Depression among Nigerian women following pregnancy loss. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2009, 105, 60–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Qin, L.; Bai, P. Self-Reported Depression among Chinese Women with Recurrent Pregnancy Loss: Focusing on Associated Risk Factors. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 7474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSpedden, M.; Mullan, B.; Sharpe, L.; Breen, L.J.; Lobb, E.A. The presence and predictors of complicated grief symptoms in perinatally bereaved mothers from a bereavement support organization. Death Stud. 2016, 41, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafarge, C.; Mitchell, K.; Fox, P. Perinatal grief following a termination of pregnancy for foetal abnormality: The impact of coping strategies. Prenat. Diagn 2013, 33, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokou-Kpolou, K.; Megalakaki, O.; Nieuviarts, N. Persistent depressive and grief symptoms for up to 10 years following perinatal loss: Involvement of negative cognitions. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 241, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozuyesil, E.; Manav, A.I.; Yesilot, S.B.; Sucu, M. Grief and ruminative thought after perinatal loss among Turkish women: One-year cohort study. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2022, 140, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horsch, A.; Jacobs, I.; McKenzie-McHarg, K. Cognitive predictors and risk factors of PTSD following stillbirth: A short-term longitudinal study. J. Trauma. Stress 2015, 28, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güçlü, O.; Şenormanci, G.; Tüten, A.; Gök, K.; Şenormanci, Ö. Perinatal Grief and Related Factors After Termination of Pregnancy for Fetal Anomaly: One-Year Follow-up Study. Noro Psikiyatr. Ars 2021, 58, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, D.C.G.; Fonseca, A.; Cameirão, M.S. The psychological impact of Early Pregnancy Loss in Portugal: Incidence and the effect on psychological morbidity. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1188060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kersting, A.; Dorsch, M.; Kreulich, C.; Reutemann, M.; Ohrmann, P.; Baez, E.; Arolt, V. Trauma and grief 2–7 years after termination of pregnancy because of fetal anomalies—A pilot study. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2005, 26, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radestad, I.; Steineck, G.; Nordin, C.; Sjogren, B. Psychological complications after stillbirth—Influence of memories and immediate management: Population based study. BMJ 1996, 312, 1505–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirtzinger, R.M.; Robinson, G.E.; Stewart, D.E.; Ralevski, E. Parameters of grieving in spontaneous abortion. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 1999, 29, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, G.F.; Montigny, F.D.; Pelloso, S.M. Factors associated with the grief after stillbirth: A comparative study between Brazilian and Canadian women. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2016, 50, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesselmann, E.D.; Parris, L. Miscarriage, Perceived Ostracism, and Trauma: A Preliminary Investigation. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 747860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.R.; Lee, J.W. Autonomy and social norms in a three factor grief model predicting perinatal grief in India. Health Care Women Int. 2014, 35, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poursalehi, P.; Dolatian, M.; Shams, J.; Nasiri, M.; Mahmoodi, Z. The path analysis between spiritual well-being and religiosity mediated by mental health and grief severity fetal or neonatal deaths. Int. J. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 12591–12601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowchock, F.S.; Lasker, J.N.; Toedter, L.J.; Skumanich, S.A.; Koenig, H.G. Religious beliefs affect grieving after pregnancy loss. J. Relig. Health 2010, 49, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridaura, I.; Penelo, E.; Raich, R.M. Depressive symptomatology and grief in Spanish women who have suffered a perinatal loss. Psicothema 2017, 29, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhard, I.M.; van den Hout, M.A.; Kindt, M.; Arntz, A.; Schouten, E. Peritraumatic dissociation and posttraumatic stress after pregnancy loss: A prospective study. Behav. Res. Ther. 2003, 41, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.X.; Lasker, J.N. Patterns of grief reaction after pregnancy loss. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1996, 66, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunfeld, J.A.; Wladimiroff, J.W.; Passchier, J. The grief of late pregnancy loss. Patient Educ. Couns. 1997, 31, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beutel, M.; Deckardt, R.; von Rad, M.; Weiner, H. Grief and depression after miscarriage: Their separation, antecedents, and course. Psychosom. Med. 1995, 57, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özgür, M.; Yıldız, H. The level of grief in women with pregnancy loss: A prospective evaluation of the first three months of perinatal loss. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 42, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, H.J.; Cuisinier, M.C.; de Graauw, K.P.; Hoogduin, K.A. A prospective study of risk factors predicting grief intensity following pregnancy loss. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1997, 54, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozgen, L.; Ozgen, G.; Simsek, D.; Dıncgez, B.; Bayram, F.; Mıdıkhan, A.N. Are women diagnosed with early pregnancy loss at risk for anxiety, depression, and perinatal grief? Saudi Med. J. 2022, 43, 1046–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farren, J.; Jalmbrant, M.; Falconieri, N.; Mitchell-Jones, N.; Bobdiwala, S.; Al-Memar, M.; Parker, N.; Van Calster, B.; Timmerman, D.; Bourne, T. Prognostic factors for post-traumatic stress, anxiety and depression in women after early pregnancy loss: A multi-centre prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e054490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slot, A.; Krog, M.C.; Bliddal, S.; Olsen, L.R.; Nielsen, H.S.; Kolte, A.M. Feelings of guilt and loss of control dominate in stress and depression inventories from women with recurrent pregnancy loss. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2022, 27, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.R.; McKeown, R.E.; Bacon, J.; Vesselinov, R.; Bush, F. Predicting depressive symptoms and grief after pregnancy loss. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2008, 29, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issakhanova, A.; Issanov, A.; Ukybassova, T.; Kaldygulova, L.; Marat, A.; Imankulova, B.; Kamzayeva, N.; Almawi, W.Y.; Aimagambetova, G. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in Kazakhstani Women with Recurrent Pregnancy Loss: A Case-Control Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farren, J.; Jalmbrant, M.; Falconieri, N.; Mitchell-Jones, N.; Bobdiwala, S.; Al-Memar, M.; Tapp, S.; Van Calster, B.; Wynants, L.; Timmerman, D.; et al. Posttraumatic stress, anxiety and depression following miscarriage and ectopic pregnancy: A multicenter, prospective, cohort study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 222, 367.e1–367.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druguet, M.; Nuño, L.; Rodó, C.; Arévalo, S.; Carreras, E.; Gómez-Benito, J. Emotional Effect of the Loss of One or Both Fetuses in a Monochorionic Twin Pregnancy. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. JOGNN 2018, 47, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulathilaka, S.; Hanwella, R.; de Silva, V.A. Depressive disorder and grief following spontaneous abortion. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidt, C.E.; Hasenburg, A.; Kunze, M.; Waller, E.; Pfeifer, R.; Zimmermann, P.; Hartmann, A.; Waller, N. Are individual differences of attachment predicting bereavement outcome after perinatal loss? A prospective cohort study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2012, 73, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersting, A.; Wagner, B. Complicated grief after perinatal loss. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 14, 187–194. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3384447/ (accessed on 28 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Kersting, A.; Brähler, E.; Glaesmer, H.; Wagner, B. Prevalence of complicated grief in a representative population-based sample. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 131, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brier, N. Grief following miscarriage: A comprehensive review of the literature. J. Women’s Health 2008, 17, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacciatore, J.; Frøen, J.F.; Killian, M. Condemning self, condemning other: Blame and mental health in women suffering stillbirth. J. Ment. Health Couns. 2023, 35, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlandsson, K.; Warland, J.; Cacciatore, J.; Rådestad, I. Seeing and holding a stillborn baby: Mothers’ feelings in relation to how their babies were presented to them after birth—Findings from an online questionnaire. Midwifery 2013, 29, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koopmans, L.; Wilson, T.; Cacciatore, J.; Flenady, V. Support for mothers, fathers and families after perinatal death. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, 6, CD000452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciatore, J. The Unique Experiences of Women and Their Families After the Death of a Baby. Soc. Work Health Care 2010, 49, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, F.; Merrell, J. Negotiating the transition: Caring for women through the experience of early miscarriage. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009, 18, 1583–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frøen, J.F.; Cacciatore, J.; McClure, E.M.; Kuti, O.; Jokhio, A.H.; Islam, M.; Shiffman, J. Stillbirths: Why they matter. Lancet 2011, 377, 1353–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| RECORD | SAMPLE | AGE | STATISTICAL TECHNIQUE | RESULTS (Risk Factors) | CONCLUSIONS |

| de Montigny et al. * [13] | Sample: 231 women over 18 years old. A minority of participants were immigrants. Socioeconomic level: A minority had a low socioeconomic level. Characteristics of the loss: In half of the women, the miscarriage had occurred less than 1 year earlier. The time elapsed since miscarriage ranged between 1 month and 4 years. The gestational age of the fetus at the time of miscarriage ranged from 3 to 20 weeks. A.O. 4: Most women had experienced 1 or 2 miscarriages (MTP 3) Living children: About 40% of participants had no children at the time of the study. | The age of the women at the time of the last miscarriage ranged from 19 to 43 years, with the majority between 25 and 35 years old (n = 170, 74%). | Descriptive statistics, one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc tests, correlations, and hierarchical regression to control for personal and contextual factors. | 55% of the women presented clinically significant depressive symptoms, 27.1% reported high levels of perinatal grief, and 18.3% showed low quality in their couple relationship. Satisfaction with the healthcare system was moderately high (M = 3.11/4.00). The risk factors associated with poorer mental health were: income ≤ 50 CAD 1 (greater depression, anxiety, and grief; p < 0.01), low educational level (greater grief; p < 0.01), being an immigrant (greater depression and grief; p < 0.05), having no children (greater overall symptomatology; p < 0.001), and having a recent loss (< 6 months), which was associated with more depression (p = 0.046). Symptoms of grief, depression, anxiety, and PTSD 2 were more intense during the first month after the loss, with reductions in the following months, but grief and depression peaked again after 7 and 37 months. | Being an immigrant, having a low socioeconomic level, and having no children significantly increase the risk of developing persistent symptoms of depression, anxiety, and perinatal grief. These factors represent conditions of vulnerability that can exacerbate the psychological impact of miscarriage. Recommendations: Greater psychosocial support and culturally sensitive care are needed for immigrant women and those with limited resources, focusing on emotional support provided by the healthcare system. |

| Gold et al. * [14] | Sample: 609 women: 232 in the control group (surviving children) and 377 in the bereavement group (191 stillbirths, 181 neonatal deaths, and 5 miscarriages). Eleven percent of the pregnancies in the bereavement group and 1% in the control group were multiple. Pregnancy losses (A.O. 4): Sixteen women in the bereavement group had at least one live birth in addition to the loss. Educational level: Two-thirds of the sample had secondary education. Time since loss: The median time between the loss/birth and the survey was 9.1 months, with no significant differences between groups. Race: Women in the bereavement group more frequently reported being African American, delivering at lower gestational age, and having a history of depression, PTSD 2, and intimate partner violence. | The mean maternal age was 29 years (±6) | Descriptive statistics, Chi-square tests and t-tests, multivariable logistic analysis, Hosmer–Lemeshow test, and analysis of the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) for each model. | Bereaved women were nearly 4 times more likely to screen positive for depression and 7 times more likely for PTSD 2, after adjusting for demographic and personal variables (AUROC = 0.83 for depression; 0.81 for PTSD 2). Independent predictors of depression were: history of depressive disorder [OR = 3.19; 95% CI: 1.85–5.50; p < 0.0005], prior PTSD 2 [OR = 3.43; 95% CI: 1.69–6.96; p < 0.001], and intimate partner violence [OR = 2.01; 95% CI: 1.03–3.92; p < 0.040]. For PTSD 2, the independent predictors were: history of depressive disorder [OR = 3.72; 95% CI: 2.34–4.93; p < 0.0005], prior PTSD [OR = 2.96; 95% CI: 1.42–6.17; p < 0.004], intimate partner violence [OR = 2.12; 95% CI: 1.09–4.13; p < 0.027], and public insurance [OR = 2.01; 95% CI: 1.19–3.39; p < 0.009]. Among bereaved Caucasian and African American women who screened positive for depression or PTSD 2 (n = 137), Caucasian women reported greater access to treatment (43% vs. 20%; p = 0.022). | Nine months after a loss, bereaved women showed notably high and persistent levels of depressive and PTSD 2 symptoms compared to those who did not experience a loss. There were no significant differences in symptom levels of these disorders according to the type of death or race. It is suggested that future research should distinguish the natural trajectories of mental health following perinatal loss. |

| Obi et al. * [15] | Sample: 202 Nigerian women. Education: 58.4% higher education, 31.7% secondary, and 9.9% primary. Religion: 97% Christian. Marital status: 90.1% married and 9.9% single. A.O. 4: For 76.2% it was their first pregnancy; 23.8% had experienced previous losses. 50.5% had no living children and the rest had one or more. The interval between the loss and the survey was 1 month (12%), 2 months (64%), and 3 months (24%). 65.8% of the losses occurred before 20 weeks of gestation. | The mean age of the participants was 26.8 ± 5.37 years. | Descriptive statistics, Chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, and logistic regression. | Minimal depression: 74.3%; moderate: 3%; severe: 13.9%; no depression: 8.9%. Factors associated with higher depression scores: previous losses (p < 0.001), loss of a male fetus (χ2, p < 0.001), having no living children (p < 0.001), late-gestation losses (p < 0.001), and being married (p < 0.001). Logistic regression: no living child (OR = 2.4; 95% CI: 1.9–2.5) and loss >20 weeks of gestation (OR = 1.9; 95% CI: 1.8–2.5) | Most Nigerian women experienced some level of depression after pregnancy loss. Main risk factors for depression: absence of living children and losses after 20 weeks of gestation. |

| Gao et al. * [16] | Sample: 247 women with a history of recurrent pregnancy loss and 193 healthy controls. Pregnancy losses A.O. 4: In the recurrent loss group, 29.2% were not pregnant, 42.9% were in the first trimester, and 27.9% were in the second or third trimester. 62.8% had experienced two miscarriages and 37.2% more than two; 14.2% had a history of loss and 67.2% a history of at least one induced abortion. | In the recurrent loss group, 83.4% were 35 years old or younger and 16.6% were 36 years or older. | Descriptive statistics, Chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, and univariate and multivariate logistic regression. | Higher prevalence of depression in the recurrent loss group (45.3% vs. 30.1%; χ2, p < 0.01). Depression prevalence was higher in the loss group when: -Women were in the first trimester of pregnancy [RR = 3.05 (1.56–5.96, p < 0.01)] -Age < 35 [RR = 1.55 (1.01–2.37, p < 0.05)] -Age > 36 [RR = 6.00 (1.70–21.21, p < 0.01)] -BMI 18.5–24 kg/m2 [RR = 3.05 (1.56–5.96, p < 0.01)] -BMI > 24 kg/m2 [RR = 3.05 (1.56–5.96, p < 0.01)] -Working < 8 h [RR = 1.90 (1.23–2.95, p < 0.01)] -University-level education or higher [RR = 1.91 (1.16–3.16, p = 0.01)] -Living in an urban area [RR = 1.83 (1.21–2.76, p < 0.01)] Logistic regression: -Age > 36 years [RR = 5.47 (2.42–12.38, p < 0.01)] -2 miscarriages [RR = 2.94 (1.66–5.22, p < 0.01)] -No live births [RR = 3.77 (1.81–7.82, p < 0.01)] | Risk factors for depression in the recurrent loss group: being 36 years or older, having had two or more miscarriages, and having no live-born children. |

| McSpedden et al. * [17] | Sample: 121 mothers in perinatal bereavement up to 5 years after the loss. | Between 23 and 53 years. | Descriptive statistics, independent samples t-tests, Cohen’s d. | 12.4% experienced complicated grief. There was a moderately significant difference in complicated grief scores between women with no living children (M = 66.33, SD = 21.88) and those with living children (M = 53.86, SD = 17.39), t = 2.85; p = 0.01, η2 = 0.06. | The absence of living children was identified as a predictor of complicated grief; previous perinatal loss and type of loss were not significant. Recommendations: The symptomatology of mothers in perinatal bereavement should be routinely monitored for referral to treatment when indicated. |

| Lafarge et al. * [18] | Sample: 166 women who terminated their pregnancy due to fetal abnormality. C.SD 5: The majority (70.5%, n = 117) had a university education; all but one were married or in a relationship, and 97.0% (n = 130) were White. Loss: Pregnancies were terminated between 12 and 35 weeks of gestation (M = 18.5, SD = 4.9). In approximately half of the participants (53%), the termination had occurred less than 6 months before participating in the study. Most were medical professionals (77.7%). A.O. 4: For 70 participants (42.2%), this was their first pregnancy. | Between 22 and 46 years (M = 34.5; SD = 4.9). | One-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post hoc test, and hierarchical regression analysis. | 12.4% experienced complicated grief. Women with no living children showed higher scores (M = 66.33, SD = 21.88) than those with living children (M = 53.86, SD = 17.39), t = 2.85; p = 0.01; η2 = 0.06. Higher levels of grief were found in women without children at the time of termination, in their first pregnancy, without subsequent pregnancies, who would not repeat (or were unsure about) the decision, and in those who had experienced grief within the previous 6 months. Women under 35 reported greater active grief. There were no differences by method of termination, gestational age, prognosis of the anomaly, or educational level. In the hierarchical regression, active grief was positively associated with guilt, religion, planning, and behavioral disengagement, and negatively with acceptance and time since termination. Coping difficulty was predicted by guilt, behavioral disengagement, venting, and negative feelings about the decision, and decreased with acceptance, positive reframing, elapsed time, and having living or subsequent children. Despair increased with guilt, behavioral disengagement, and negative feelings about the decision, and decreased with acceptance and having living or subsequent children. Overall grief increased with guilt, behavioral disengagement, venting, planning, religion, and feelings about the decision, and decreased with acceptance, positive reframing, elapsed time, and having living or subsequent children. | This study indicates that there is a relationship between the coping strategies women use when facing a termination and their levels of grief. After controlling for obstetric and termination variables, women who reported using strategies such as acceptance and positive reframing showed better psychological outcomes than those who used maladaptive strategies, such as guilt or behavioral disengagement. Grief levels in this study varied according to obstetric and termination variables, with higher levels of grief among women with more recent loss, those without children at the time of termination, those who were not pregnant nor had children since the termination, and those who would not make the same decision again or were unsure about it. Recommendations: It may be beneficial to promote protective strategies through information or therapies such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)–based interventions or Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). |

| Kokou-Kpolou et al. * [19] | Sample: 98 French women. Education and employment: 43.9% had university education and 55.1% had a high school diploma. Almost all were employed (full-time or part-time). Loss: On average, the loss had occurred 40.48 months earlier (SD = 28.92, range 3–120). For most of the sample (71.4%), the loss had been unexpected. 67.9% of the women had lost the child before birth and 32.1% after. Pregnancy history A.O. 4: For 42.9% it was their first child, while 56.1% already had at least one other child. | Mean age was 33.89 years (SD = 5.34). | Descriptive statistics, partial correlation analysis, MANCOVA, and hierarchical regression analysis. | Acute grief reactions were significantly correlated with depressive symptoms [r(94) = 0.78, p < 0.001], controlling for age and time since loss, but mothers who had at least one other child reported fewer depressive symptoms [F(2,95) = 3.65, p = 0.06, η2 = 0.032]. With the exception of guilt, all forms of negative cognition were correlated with acute grief reactions (p < 0.001) and depressive symptoms (p < 0.001). Hierarchical regression: The model including all negative cognitions was significant [F(5,86) = 11.78, p < 0.001] and explained 37.2% of the variance in acute perinatal grief. Three negative cognitions were associated with grief: cognitions about life (ß = 0.381, p = 0.003), the world (ß = 0.198, p = 0.032), and the future (ß = 0.248, p = 0.036). Among the variables related to the loss, type of death was associated with depressive symptoms (ß = 1.05, p < 0.05). Negative cognitions about the world (ß = 0.794, p < 0.003) and negative cognitions about oneself (ß = 6.22, p = 0.051) were associated with depressive symptoms (the latter marginally). Higher depression scores were associated with increased negative cognitions about the world when the child’s death occurred before birth [type of death × cognitions about the world (ß = –1.22, p = 0.012)], and also with negative self-beliefs when neonatal death occurred [type of death × cognitions about oneself (ß = 1.06, p = 0.015)]. | Risk factors for complicated perinatal grief: negative cognitions about life, the world, and the future; negative self-beliefs; and neonatal death. Recommendations: The findings may help improve the effectiveness of secondary prevention interventions. |

| Gozuyesil et al. * [20] | Sample: 57 women. Gestational characteristics: Pregnancy loss occurred on average at 15.42 weeks (±6.61), within a range of 4 to 32 weeks. 45.7% experienced miscarriage and 54.3% stillbirth. Sociodemographic characteristics C.SD 5 Educational level: 51.4% university or higher, 30% primary, and 18.6% secondary. Occupation: 78.6% unemployed. Partners’ education: 50% university or higher, 28.6% secondary, and 21.4% primary. Income: 60% perceived their income as moderate. Residence: 60% urban area. Family type: 80% nuclear. Pregnancy history A.O. 4: 74.3% had had more than one pregnancy. 60% had never had children. Losses: 55.7% one, 28.6% two, and 15.7% three or more. Number of pregnancies: 28.6% first, 30% second, 20% third, and 21.4% fourth or more. | The mean age of the participants was 30.34 ± 6.55 years. | Descriptive statistics, Chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, Mann–Whitney U test, Kruskal–Wallis test, one-way ANOVA, Spearman correlation, and multiple linear regression with backward elimination. | A statistically significant difference was found in the mean total score of the Perinatal Grief Scale at three months as a function of age and absence of children. The difference by age was due to the 20–29-year-old group (p < 0.05). The median total scores on the Perinatal Grief Scale among women without children were higher three months after the loss compared to other times (p < 0.05). Positive correlations were found between the total score of the Ruminative Thought Style Questionnaire, the Perinatal Grief Scale, and its subscales (p < 0.05). Multiple linear regression: Active grief (β = 1.325; p = 0.003) and having an extended family (β = 15.781; p = 0.047) were statistically significant in the regression model, which explained 15.6% of the variance in the Ruminative Thought Style Questionnaire score. | Risk factors for perinatal grief: three months after the loss, women aged 20 to 29 had higher grief scores than other age groups, and not having children increased the median score on the Perinatal Grief Scale. As rumination increased in women during the initial period after the loss, grief also increased. |

| Horsch et al. ** [21] | Sample: 65 women who had a stillbirth at 24 weeks of gestation. A.O. 4: The mean number of living children was 0.51 (SD = 0.81), the mean gestational age was 34.09 weeks (SD = 5.95), the mean number of previous pregnancies was 2.15 (SD = 1.41), and the mean number of previous perinatal losses was 0.38 (SD = 0.80). 6.2% were currently taking psychotropic medication. C.SD 5: 86.2% were from the United Kingdom, 61.5% were married, 58.5% had full-time employment, 24.6% had experienced a perinatal loss prior to the stillbirth, and 70.8% reported that the pregnancy was planned. | Mean age was 31.92 years (SD = 4.98). | Multiple imputation of normal models, t-test, multiple regression analysis, using Barnard and Rubin’s adjusted degrees of freedom rounded down. | Dysfunctional strategies explained only 5.1% of the variance in PTSD 2 symptoms; rumination and numbing were positively correlated with their frequency. In regression, dysfunctional strategies explained 25.9% of the total variance (PDS), with rumination being the only positive predictor. Negative appraisals explained 42.2% of the variance in the number and 53.4% in the frequency of symptoms. Negative cognitions about oneself and the world increased symptoms, while higher guilt was related to fewer symptoms. At follow-up, suppression and distraction predicted a decrease in symptoms at 6 months, while lower numbing was also protective. Perceived social support showed consistent negative associations with symptom frequency at 3 and 6 months. Sociodemographic factors also played a role: higher maternal age predicted fewer avoidance symptoms (β = −0.25; p = 0.048); having more children (β = −0.32; p = 0.021) and previous pregnancies (β = −0.31; p = 0.012) reduced avoidance at 6 months. Likewise, greater social support (β = −0.26; p = 0.030) predicted fewer re-experiencing symptoms, and higher income (β = −0.29; p = 0.010) predicted fewer arousal symptoms. | Our findings showed that intrauterine fetal death can be experienced as a traumatic event and can generate clinical levels of maternal distress. At 3 months, greater rumination was specifically related to more frequent self-reported PTSD 2 symptoms. Negative appraisals, particularly about oneself and the world, predicted PTSD 2 symptoms at 3 months. Higher scores on suppression and distraction, and lower scores on numbing, were associated with fewer PTSD 2 (SCID) symptoms at 6 months. Regarding risk factors, perceived social support was negatively associated with self-reported PTSD 2 symptoms at both time points. Our results indicate that cognitive-behavioral techniques should be an important component for mothers seeking help for clinical levels of PTSD 2 after intrauterine fetal death, and these should be primarily aimed at addressing negative cognitive appraisals related to self-identity and the world, as well as dysfunctional strategies, particularly rumination. Women’s social networks should increase their support following intrauterine fetal death. |

| GüÇlü et al. ** [22] | Sample: 46 women who decided to terminate their pregnancy due to a fetal abnormality. A.O. 4: Only three participants had children; four women mentioned that they had also terminated previous pregnancies. C.SD 5: 8.7% had a university education, 39.1% had completed high school, 19.6% secondary school, and 32.6% primary school. The majority had a nuclear family, were unemployed (73.9%), had an income below 1500 (80.4%), had been married for less than 6 years Pregnancy: (65.2%), had a natural pregnancy (95.7%). 13% had a consanguineous pregnancy, 13% terminated their pregnancy due to a previously diagnosed abnormality, 58.7% were clear about the abnormality, and 54.3% reported understanding the abnormality. In 65.2% of cases, the expected outcome of the abnormality was both physical and mental. The baby’s life expectancy was considered short-to-medium in 50% and long in the other 50%. The partner’s role in the decision was effective in 65.2% of cases, and 50% considered that the economic situation had an influence. | The mean age of the women was 29.6 ± 6.4 years. | Descriptive statistics, t-test, ANOVA, repeated measures ANOVA, Bonferroni post hoc, Pearson correlation, and linear regression. | No correlation was found between the severity of grief symptoms and patients’ sociodemographic or clinical characteristics. In the linear regression, Hyperarousal (β = 1.172, p = 0.016), relational satisfaction (β = −1.761, p = 0.006), and secure attachment (β = −1.19, p < 0.077) were predictors of the total grief score in the first year. | Grief symptoms were not associated with intrusion or avoidance but rather with signs of hyperarousal, both in the short- and long-term grief. Hyperarousal scores and relational satisfaction proved to be predictors of total perinatal grief scores during the first year. In our study, a weak-to-moderate significant negative relationship was observed between secure attachment and grief, both short- and long-term. A weak-to-moderate significant positive relationship was found between ambivalent attachment and difficulty coping with perinatal grief. A negative correlation was also observed between relational satisfaction and active grief. Recommendations: To identify parents who need follow-up after perinatal loss, a clinical tool should be developed. In addition, it could be useful to focus on counseling and even more specific trauma techniques and couples therapy to assist in the grieving process. |

| Mendes et al. * [23] | Sample: 873 women over 18 years old, mostly Portuguese (99%) and non-immigrants (98.6%), from all regions of Portugal. Marital status: 88.9% married or cohabiting; 8.8% single. Living children: 61.7%. Educational and employment level: 80.2% had higher education, 93.2% were employed, 96.6% had income above the minimum wage. Pregnancy losses (A.O. 4): 69.2% reported a single gestational loss. Fertility: 84.4% had no infertility diagnosis; 86.4% had not undergone assisted reproductive techniques (ART). Mental health: 71.4% had no diagnosis of mental disorders; 62.4% had not received past or current psychological treatment. Characteristics of the loss: 91.1% spontaneous pregnancies; 81.4% planned pregnancies; 95.6% single pregnancies; clinical cause of the loss mostly unknown. | Participants’ ages ranged from 21 to 57 years (M = 36.04, SD = 4.9). | Descriptive statistics, one-way independent samples ANOVA, effect sizes calculated using eta squared, multiple post hoc comparisons with Bonferroni correction, and Chi-square tests. | Women assessed between 0 and 1 month after the loss showed higher levels of perinatal grief [F(6,866) = 7.67, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.051] and a greater proportion of clinical symptoms (χ2 = 34.5, p < 0.001, φ = 0.20). Scores decreased significantly at 4–6 months, but there was an increase of about 10% in the ≥37-month group compared to the 25–36-month group. Clinical anxiety was more prevalent in the 0–1 month group (mostly moderate), although the highest mean scores were recorded between 7–12 months. After a decrease between 2–3 months, levels remained stable. Depressive symptoms were highest in the 0–1 month group [F(6,866) = 2.80, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.019], with a higher frequency of mild cases. A reduction was observed at 2–3 months, although variations persisted in groups with losses greater than 3 months, with a second peak at 7–12 months. The highest PTSD scores also appeared in the first month [F(6,866) = 4.41, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.030], with more clinical cases in that period (χ2 = 14.5, p < 0.02, φ > 0.13), decreasing progressively from 13–24 months onward. | The study provides evidence that symptoms of anxiety and depression may persist between one and three years after the event. It is suggested that future studies focus on the factors that may predict complex mental health responses. |

| Kersting et al. * [24] | Sample: 83 women, compared with 60 women 14 days after pregnancy termination and 65 women after a spontaneous delivery of a healthy full-term child. Loss: Termination was performed between 15 and 33 weeks of gestation (M = 21.01, SD = 3.77). At the time of the survey, the mean period since termination was 4 years (M = 4.1, SD = 1.9). The fetal diagnosis included chromosomal abnormalities or multiple fetal malformations. | The mean age at the time of pregnancy termination was 31.9 years (SD = 4.6). | Descriptive statistics, one-way ANOVA with Scheffé post hoc comparisons, and unpaired t-test. | Women who underwent pregnancy termination, both at 4 years and at 14 days, reported a significantly higher degree of traumatic experience than mothers after spontaneous delivery. Significant differences (p = 0.000) were reflected in all subscales and in the total scores of the Impact of Event Scale. Women 2 to 7 years after pregnancy termination had a mean score of 2.64 (SD = 0.62) and those 2 weeks after termination had a mean score of 2.86 (SD = 0.55) (p = 0.064) on the Perinatal Grief Scale, only in the subscale fear of loss. | The study results show a degree of persistence of post-traumatic stress response that is detectable even years after the event. |

| Radestad et al. * [25] | Sample: 636 women (314 in the study group and 322 in the control group). C.SD 5: Marital status was similar, while the level of education was lower in the study group. | The mean age was the same in both groups (32 years). | Descriptive statistics, proportion ratio, Fisher’s exact test, and logistic regression models. | Women with stillbirth had higher anxiety scores (mean = 1.82; median = 1.65; P10 = 1.25; P90 = 2.55) than controls (mean = 1.74; median = 1.65; P10 = 1.30; P90 = 2.25). Ten percent of women with stillbirth exceeded 2.55, compared to 5% of controls (proportion ratio = 2.1; 95% CI: 1.2–3.9; p = 0.01). Among those who waited ≥25 h between diagnosis and the start of labor, 23% had anxiety above P90, compared to 5% of those who did not wait (p = 0.004). Women who reported not having seen their baby for the desired amount of time also showed anxiety close to P90 (p = 0.004). No significant differences were found among those who did not touch their baby. Elevated anxiety was observed in 7% of those who had memories of their baby, versus 22% of those without memories (p = 0.002). In logistic regression, seeing the baby for the desired amount of time, not having memories, and the diagnosis–delivery interval contributed significant information (p = 0.01), while the absence of a subsequent pregnancy did not (p = 0.3). | Risk factors for anxiety: A strong association was observed between waiting more than 24 h before the onset of labor after the diagnosis of intrauterine death and anxiety-related symptoms. Not seeing the baby for as long as the woman desired and the lack of concrete memories increased the risk of anxiety- or depression-related symptoms. |

| Stirtzinger et al. * [26] | Sample: 175 women at 3 months and 119 women at 1 year after miscarriage. A subgroup of 39 women was assessed at both 3 months and 1 year. A.O. 4: 71% of the women in the 3-month group and 69.7% in the 1-year group were younger than 30 years. Among the women assessed 3 months after the loss, 81.1% had experienced miscarriage (vs. 80.7% at 1 year). 28.6% had no live child (vs. 30.3% at 1 year). The mean gestational age was 9.9 weeks (SD = 4.2) (vs. 11.5 weeks, SD = 4.1). The mean number of miscarriages was 2.4 (SD = 1.7) (vs. 1.9, SD = 0.8 at 1 year), and the mean number of live children was 0.9 in both groups. | The mean age of the women assessed three months after miscarriage was 37.7 years (SD = 4.8), and of those assessed one year after, 33.6 years (SD = 5.7). | Descriptive statistics, analysis of variance with three independent factors, and post hoc comparisons using Tukey’s test. | Among women who responded 3 months after miscarriage: Post hoc analysis showed that those <30 years old with multiple miscarriages had significantly higher depression scores than women >30 years old with multiple miscarriages (p = 0.05). Moderate problems with spouse or family were significantly associated with higher depression scores compared to those who did not report problems (p < 0.05). Women who felt partly guilty had a mean depression symptom score of 23.5 (SD = 11.7), while those who felt completely guilty had a mean score of 40.4 (SD = 6.9) (p < 0.01). Women who rated the miscarriage as highly stressful presented higher depression scores (p < 0.05). One year after miscarriage: Post hoc analyses indicated that women who had experienced multiple miscarriages but had living children presented significantly lower depression symptoms than women without children (p < 0.05). Women without living children and >30 years old showed greater depressive symptomatology at one year. | Risk factors for depression three months after the loss: Age under 30, multiple miscarriages, moderate or severe problems with spouse or family, and feelings of guilt. Risk factors at one year: Being over 30 years old and having no living children; mild or moderate problems with spouse. Recommendations: Awareness of specific risk factors that may intensify or prolong grief—such as problems with spouse or family, guilt, being blamed by others, age at the time of loss, and number of living children—may be useful in preventing complicated grief. |

| Paris et al. * [27] | Sample: 44 women with stillbirth. Residence: 26 residents in Maringá, Brazil, and 18 residents in Canada. | The mean age was not reported; the variable was categorized into 20–34 years and <20 or >35 years. | Odds ratio (OR) and multivariate multiple correspondence analysis. | The prevalence of complicated grief was 35% among Brazilian women and 12% among Canadian women. In Brazil, it was associated with age between 20–34 years, absence of a partner, ≤12 years of education, lack of employment (p > 0.05), not practicing religion, and not receiving religious visits (p < 0.05). In Canada, only absence of religion was related to complicated grief, while not receiving religious visits acted as a protective factor (p > 0.05). Regarding reproductive characteristics, in Brazil it was linked with a previous pregnancy with a living child, unwanted pregnancy, and absence of prior losses; in Canada, with losses occurring within the past year. In both countries, gestation longer than 28 weeks was also associated with complicated grief (p > 0.05). In terms of mental health, in Brazil it was related to high levels of anxiety (p > 0.05) and postpartum depression (p < 0.05). In both groups, marriages lasting less than 5 years increased grief; in Canada, almost all indicators of low marital satisfaction were also associated (p > 0.05). Finally, multiple correspondence analysis showed that Brazilian women require greater attention: they lack professional support, consider separation, do not practice religion, and have lower educational levels. | Factors for complicated grief: women living in Brazil, not seeking professional support groups, having little or no marital satisfaction, not practicing any religion, and having a low educational level. |

| Wesselmann and Parris * [28] | Sample: 97 women. Pregnancy losses (A.O. 4): On average, they had 1.54 miscarriages (mode = 1; SD = 0.85; Min 1–Max 5). Race: Most participants identified as White/Caucasian (79.8%); 3.4% as Asian American/of Asian descent; 8.4% Black/African American; 8.4% Hispanic/Latina; 2.5% Native American/Indo-American; 2.5% biracial/multiracial; and 3.4% unspecified. Marital status: Most participants (52.6%) were in stable relationships (married/in legal union), 23.7% were divorced/separated, 15.5% were single, and 8.2% were widowed. | Women between 18 and 87 years old. The mean age was 51 (SD = 18.34). | Descriptive statistics, bivariate correlations, multiple regression analysis, and relative weight analysis. | Participants who reported greater ability to cope with problematic interactions (r = −0.26; p < 0.01) and greater congruence between their miscarriage experience and the support received (r = −0.54; p < 0.01) showed fewer post-traumatic stress symptoms. In contrast, ostracism was negatively associated with congruence (r = −0.34; p = 0.001) and positively associated with post-traumatic stress symptomatology (r = 0.54; p < 0.001). Multiple regression analysis indicated that perceived ostracism explained the largest variance and was the most significant predictor of increased post-traumatic stress symptoms. | Women who perceived more ostracism reported higher levels of post-traumatic stress symptoms. Recommendations: Perceived ostracism should be considered as a factor that may contribute to and prolong post-traumatic stress processes. |

| Roberts and Lee * [29] | Sample: Cohort of 355 women from a rural area in central India, divided into 178 who had experienced stillbirth and 177 who had not. Cases with missing data in the analysis variables were excluded from the final analysis, leaving 347. | The mean age and age range of the participants were not reported. | Descriptive statistics, principal component analysis to eliminate items, simple linear regressions, and structural equation modeling. | Predictors of perinatal grief in linear regression: education, age at first childbirth, number of pregnancies, number of stillbirths, and social norms. In the regression analysis, only social norms were significant (p < 0.01), with a moderate explained variance (R2 = 0.26). Principal component analysis showed that grief was modeled in three factors: self-despair, difficulty coping, and acute grief. Acceptance of social norms was positively associated with self-despair and forced coping, while negatively associated with autonomy. Autonomy was positively associated with acute grief. Both self-despair and acute grief were positively associated with difficulty coping. | Acceptance of traditional social norms was associated with greater despair and difficulty coping. Greater autonomy was associated with more acute grief. Recommendations: Future interventions aimed at reducing the social and mental health consequences of perinatal grief should also address the underlying social norms that shape the context of Indian women’s lives. |

| Poursalehi et al. * [30] | Sample: 200 women with perinatal death. C.SD 5: The majority (60.5%) were housewives, and 42% had one child. | The mean age of the participants was 29.66 ± 5.56 years. | Descriptive statistics, Pearson correlation, and path analysis | There is a negative correlation between grief severity, spiritual health, and religiosity. In other words, as spiritual well-being decreased, grief severity increased. In addition, grief severity was negatively correlated with mental health: the better the mental health was, the lower the grief severity was. Spiritual well-being showed the strongest negative correlation with grief severity and all its subscales, except for coping (p < 0.05). Direct and indirect effects: Religiosity presented the strongest negative relationship (β = −0.838), and among the variables related to grief in only one direction, mental health showed the strongest positive relationship (β = 0.33). | The results of this study showed a significant relationship between the level of spiritual well-being and mental health with grief severity. A significant relationship was also observed between the level of religiosity and grief severity, such that as religiosity increased, grief severity decreased. |

| Cowchock et al. ** [31] | Sample: 110 women interviewed between 4 and 6 weeks after the loss who also completed at least one interview 1 or 2 years later. Religion: The majority were Christian, 3 were Jewish, 1 was Mormon, and 3 reported having no religion. 12% mentioned fundamentalist denominations ranging from Baptist to Mennonite, and nearly one-third of the sample was Catholic. Loss: Types of losses ranged from ectopic pregnancies (16%) to intrauterine fetal death (27%) or infant death (11%). Most frequently, the loss occurred in the first trimester (46%). | The mean age at the first interview was 28 years (range 16–45). | Descriptive statistics and simple correlation analysis. To compensate for multiple comparisons in this study, statistical significance was defined as a p-value < 0.01 for all analyses. A “trend” referred to p-values between 0.02 and 0.09. All p-values are two-tailed. | Negative religious coping was strongly correlated with total grief scores at 6 weeks (r = 0.54, p < 0.001) and at 1 year (r = 0.34), as well as with the three subscales at both time points. Intrinsic religiosity showed a trend toward a negative correlation with difficulty coping (r = −0.16 to −0.22; r = −0.22, p = 0.02 at 1 year). Similarly, belief in God was associated with lower grief scores on the difficulty coping subscale (r = −0.19 to −0.23; p = 0.02–0.05), although the skewed distribution of responses limits interpretation. Continued attachment to the deceased baby was consistently related to higher total grief and active grief scores. Additionally, religious struggle predicted higher levels of total grief across all periods, especially for difficulty coping and despair. | Women who experience pregnancy loss and use negative religious coping strategies or express religious struggles are at high risk of suffering from chronic or even pathological grief one or two years after the event. |

| Ridaura et al. ** [32] | Sample: 70 participants, 41 completed the second follow-up and 36 the third. A.O. 4: 71% had experienced perinatal loss due to IME; the average gestational age at the time of loss was 22.4 weeks (SD = 5.61). For those who experienced perinatal death not due to IME, the mean was 25.7 weeks (SD = 4.77), and for postnatal death, 35 weeks (SD = 3.21) with a median of 4.5 days of postnatal life. The mean number of previous miscarriages was 0.54 (SD = 1.03) and the mean number of healthy live-born children was 0.36 (SD = 0.57). Marital status: Most were married (82.9%). Socioeconomic level: Middle (41.4%) or low (44.3%). | The mean age of the sample (n = 70) was 32.12 years (SD = 4.68). | Descriptive statistics; 2 × 3 mixed-design ANOVA (group × time); effect size with Cohen’s d; and multiple linear regression models. | 1- No significant association was found between sociodemographic factors (age and socioeconomic level) or obstetric factors (gestational weeks at the time of loss, presence of children, and previous miscarriages) and active grief scores. 2- A significant positive association was found between gestational weeks and depressive symptoms (β = 0.29; p = 0.018). | Depressive symptoms are observed at the time closest to the loss. Grief-related symptoms decrease more gradually over the year following the loss. The type of loss is not related to better or worse progression of grief scores. A more advanced gestational stage at the time of loss is associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms one month afterward. |

| Engelhard et al. ** [33] | Sample: 126 women with pregnancy loss; 118 completed the questionnaire one month later and 104 four months after the loss. Marital status: Almost all were married or cohabiting. Education: Around 40% had university education. A.O. 4: About 30% had no children. Loss: The mean gestational age at the time of loss was 12 weeks (SD = 6, range 5–40), and 95% occurred before 20 weeks of gestation. | 31 years (SD ± 4). | Residual estimation adjustment, Pearson correlations, multiple regression, polychoric, polyserial, and product-moment correlations, and degree of consistency of the hypothetical pathways with the data using the weighted least squares method. | Peritraumatic dissociation (ß = 0.36, t = 4.48, p < 0.001), neuroticism (ß = 0.22, t = 2.75, p = 0.007), emotional control (ß = −0.17, t = 2.23, p = 0.028), and previous negative events (ß = 0.16, t = 2.13, p = 0.035) explained 33% of acute PTSD symptoms, F(4,113) = 13.67, p < 0.001. The relationship between peritraumatic dissociation and acute PTSD 2 symptoms was mainly mediated by memory fragmentation and thought suppression related to pregnancy loss. The relationship between peritraumatic dissociation and chronic PTSD 2 symptoms was mediated by acute symptoms. | Peritraumatic dissociation was strongly related to both acute and chronic PTSD 2 symptoms. Risk factors for PTSD: Higher peritraumatic dissociation, greater neuroticism, lower emotional control, and more previous negative events. |

| Lin and Lasker * [34] | Sample: 138 women. Sociodemographic characteristics (C.SD 5): The majority were White and married (94%); 5% were of Hispanic origin and 1% African American; most had completed an average of 13.5 years of education. Loss: 63 had experienced miscarriage, 18 ectopic pregnancy, 39 stillbirth, and 18 neonatal death. | The mean age of the women was 28.5 years, with a range of 15 to 41 | Descriptive statistics, ANOVA, MANOVA, and functional discriminant analysis. | Seven grief patterns were identified, grouped into four groups: Group 1 (categories 1–2), Group 2 (3 and 7), Group 3 (4–5), and Group 4 (6). Multivariate analysis showed significant differences between groups according to age, education, children at the third interview, subsequent loss, birth, children at the time of loss, gender, and social support (F = 2.26, df = 21, p < 0.001). Discriminant analysis indicated that age, children at the time of loss, and subsequent pregnancy explained 62.74% of the variance; gender and children two years after the loss explained 27.34%; and education together with social support explained 9.92%. | Differences between groups reflect some extended effects of age and education. Other factors that played an important role in reducing the intensity of grief over time were: subsequent birth, subsequent pregnancy, and the presence of children at the time of the third interview. |

| Hunfeld et al. ** [35] | Sample: 46 women with fetal anomaly. Pregnancy losses A.O.4 Gestational age ranged from 24 to 38 weeks (median = 31). At the first measurement, 31 of the 46 women had given birth: 21 babies died before or during delivery, 7 died afterward, and 3 women delivered live babies. At the second measurement, all women had given birth. Loss: Of the total sample of newborns, 36 died within the first 28 days and one died 28 days after birth. The final sample for both measurements was 29. | Between 19 and 44 years, with a median of 30 years (n = 46). | t-test and Pearson correlation. | At 3 months after birth, stress and grief had not decreased, while difficulty coping had increased significantly. Between 3 months and 4 years after the loss, a reduction was observed in overall grief, active grief, and intrusive images. A significant correlation was found between personal inadequacy (lability, depression, anxiety, low self-esteem) and both stress and grief at 3 months and years after the loss. Likewise, personal inadequacy was positively associated with general psychological distress, and social inadequacy with hopelessness and coping difficulties at 3 months. | Regarding the association between inadequacy and grief, this indicates that coping with loss is determined not only by specific problems but also by the way a person copes with major life events. Suggestions: Provide prenatal care in cases of threatened pregnancy loss, and offer parents the opportunity to preserve evidence of the birth and brief life of the baby. |

| Beutel et al. * [36] | Sample: 125 women after miscarriage (before 20 weeks of gestation), assessed at 6 months (n = 94) and 12 months (n = 90). Eighty women with an uncomplicated pregnancy formed the control group, and 125 women from a random community sample formed the community controls. Sociodemographic characteristics C.SD 5: Most women in both groups were married and worked part-time. The control group had a higher educational level than the study group and the community control group. Pregnancy losses A.O. 4: Less than half of the women had children; between one-fifth and one-sixth of the women in both groups had experienced previous miscarriages. SM 6 42% of the study group reported previous depression, with a significantly higher incidence (19%). In both groups, 25% of depressive episodes had occurred in the year immediately prior to the study. 22% of both groups had attended psychotherapy or psychiatry for these symptoms. | The mean age of the women in the study group was 31 years, and they were on average 1.5 years older than the control group. | Descriptive statistics, F-test, correlation, ANOVA, Chi-square, Kruskal–Wallis, and MANOVA. | Patients in the study group had significantly higher depression scores than pregnant controls (p < 0.05) and community controls (p < 0.001). Immediately after miscarriage, women with a grief reaction (n = 125) showed more anxiety than those without this reaction. In addition, the grief group had higher scores for fear of loss and anger, while sadness was lower in those who did not react with grief. Patients with combined depression and grief reactions reported more guilt, numbness, disbelief, worthlessness, and suicidal ideation than others. Grief was associated with greater commitment and attachment to the pregnancy, expressed in fantasies, dreams, and preparations, while depression was linked to ambivalence toward the pregnancy, lower educational and social support, prior stress, and depressive history. The combined reaction group also showed greater disagreement with their partner. At 6 months, physical complaints (F(3,90) = 6.16; p < 0.001) and anger (F(3,90) = 5.19; p ≤ 0.01) remained elevated in the depression and combined groups, but low in grief and others. Sadness and fear of loss decreased in all groups. Anxiety normalized in grief but remained high in depression and combined reaction (F(3,90) = 2.68; p < 0.05). One year later, women with a combined reaction reported lower perceived support, greater partner discord (F(3,90) = 3.77; p < 0.05), and greater use of sleeping pills (χ2 = 8.68; p < 0.05). | Compared with a representative community sample and pregnant controls, depression scores increased immediately after miscarriage. However, 6 and 12 months later, they decreased, although they remained elevated compared to the general population. Anxiety scores increased only in patients immediately after miscarriage. More data are needed to confirm this approach to measuring grief reactions and distinguishing them from depressive reactions. |

| Özgür and Yıldız ** [37] | Sample: 215 women with pregnancy loss. C.SD 5: 62.8% had secondary or high school education (50%) and 70.2% were unemployed. A.O. 4: There was a history of miscarriage in 98.6% of the women. The current pregnancy was single, spontaneous, and planned in most cases. Loss: The majority (99.1%) of pregnancy losses were due to intrauterine fetal death, while the most common causes of pregnancy termination were congenital anomalies incompatible with life (28.8%) and potentially life-threatening maternal illnesses (20.4%). | The majority of women were in the 25–35 age group. Mean age was 30.7 years (SD = 5.9). | Descriptive statistics, t-test, one-way ANOVA, Scheffé post hoc test, repeated measures ANOVA, and Pearson correlation analysis | Active grief scores were higher in older women (36 years) than in younger women (24 years) at 48 h (p = 0.03; p < 0.01) and at 3 months (p = 0.05; p = 0.03). Despair at 48 h was greater in women with lower education levels (p = 0.04). At 3 months, active grief and coping difficulty were higher in unemployed women (p < 0.01; p = 0.04). Regarding pregnancy loss, total and subscale PGS scores were higher in assisted pregnancies than spontaneous ones, planned versus unplanned pregnancies, with or without prenatal care, and in those not desired by the husband. Coping difficulty was greater in women with no history of loss (48 h: p = 0.05; 3rd month: p = 0.04) and in late losses (32–40 weeks) compared to early losses (<31 weeks) (p < 0.01). They were also higher in women who did not consider the baby’s sex important (active grief: p = 0.01 and p < 0.01; coping: p < 0.01; total: p < 0.01). Correlations: -Maternal age: positively associated with active grief at 48 h (r = 0.19, p < 0.001), despair at 48 h and 3 months (r = 0.13 and r = 0.14, p < 0.05), and total perinatal grief score at 48 h (r = 0.13, p < 0.05). -Duration of marriage: negatively correlated with active grief at 3 months (r = −0.15, p < 0.05) and coping at 48 h and 3 months (r = −0.12 and r = −0.14, p < 0.05). -Parity and number of children: negative correlation (r = −0.35 to −0.20; p < 0.01). -Importance of the baby: positive correlation with all subscales (r = 0.29–0.68; p < 0.01). -Miscarriages and previous losses: positive correlation with coping, despair, and total score (r = 0.18–0.35; p < 0.01). | The findings indicate that advanced maternal age, primiparity, and assisted and planned pregnancies with regular prenatal care were associated with higher total scores on the Perinatal Grief Scale, as well as higher scores for active grief, coping difficulty, and despair in women, regardless of the timing of the evaluation within the 3 months following pregnancy loss. In addition, unemployment and recent marriages were associated with the prolongation of active grief and the continuation of coping difficulty up to the third month. |

| Janssen et al. ** [38] | Sample: 227 women who experienced an involuntary pregnancy loss. | Repeated measures analysis and hierarchical multiple regression. | Grief intensity was significantly associated with gestational age, neuroticism, prior psychiatric symptoms, and family composition. Women with longer pregnancies, older age, a neurotic personality, more prior psychiatric symptoms, or no living children showed more intense grief reactions, although these decreased over time. The effect of gestational age was significant for active grief (F = 55.17, df = 1210, p < 0.001), coping difficulty (F = 27.03, df = 1210, p < 0.001), and despair (F = 19.12, df = 1210, p < 0.001). Neuroticism also influenced active grief (F = 39.02, df = 1210, p < 0.001), coping (F = 58.61, df = 1210, p < 0.001), and despair (F = 49.52, df = 1210, p < 0.001). Prior psychiatric symptoms were associated with greater active grief (F = 14.71, df = 1608, p < 0.001), coping difficulty (F = 8.39, df = 1608, p = 0.004), and despair (F = 7.80, df = 1608, p = 0.006), especially shortly after the loss. Gestational age interacted with time, showing greater despair in later losses (F = 4.07, df = 1608, p = 0.04). Likewise, women with physical symptoms presented more despair shortly after the loss, although this difference decreased over time. Finally, poor partner relationships were associated with greater despair (F = 3.32, df = 1210, p = 0.07). | Advanced maternal age, primiparity, and assisted or planned pregnancies with prenatal care were associated with higher scores on the Perinatal Grief Scale and its subscales within 3 months of the loss. Unemployment and recent marriages prolonged active grief and coping difficulty. Women with longer pregnancies, prior psychiatric symptoms, a neurotic personality, or no children showed greater grief intensity. The same was true for those with more physical symptoms, poor partner relationship quality, or little social support, although these factors were less decisive. In contrast, prior loss was not related to grief intensity. Older women experienced greater difficulty coping. The only significant interaction was between prior psychiatric symptoms and time since loss, both in total score and in subscales. Recommendation: In cases of gestational loss, especially early ones, health professionals should provide individualized care and additional support to prevent grief disorders. | |

| Ozgen et al. * [39] | Sample: 116 women who had experienced early pregnancy loss. Loss: 39.6% of the patients had a missed miscarriage, 39.6% had a spontaneous miscarriage, and 20.7% had an anembryonic pregnancy. | The mean age of women with missed miscarriage was 31.5 years (range 20–44) (n = 46); with spontaneous miscarriage, 30 years (range 20–40) (n = 46); and with anembryonic pregnancy, 29.5 years (range 19–42) (n = 24). | Descriptive statistics ANOVA Chi2 | The analysis revealed that the medians calculated for women in all groups indicated moderate anxiety. The EPDS also showed positive median values for depression among women in the three groups (EPDS > 13). However, no statistically significant differences were observed in the comparisons of the three groups with respect to the STAI-1, EPDS, and PGS. There were no significant differences in the proportion of women with missed abortion, spontaneous abortion, or anembryonic pregnancy who presented symptoms above the cutoff point for depression and anxiety. | This study revealed that early pregnancy loss was associated with moderate anxiety and depression, regardless of the type of miscarriage. |

| Farren et al. * [40] | Sample: 737 women with early pregnancy loss. Loss: 366 cases were spontaneous miscarriage, 75 ectopic pregnancies, and 51 other diagnoses; 59% required surgical management; 8% were IVF 7 pregnancies. C.SD 5: 55% had a university degree, 61% had been trying to conceive for one year or less, 79% had no prior psychiatric disorders, 37% had not had a previous pregnancy loss, 41% had no children, and the majority were White. | The mean age was 35 ± 5 years. | Descriptive statistics, univariable logistic regression, area under the curve (AUC), and Nagelkerke R2. | The strongest predictor was a previous or current diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder: 75% (15/20) of those reporting a current diagnosis met criteria for anxiety, depression, or PTSD 2 (AUC = 0.61, R2 = 8.4%, p < 0.0001). Women with previous losses were also at higher risk: 48% (86/180) met criteria for a disorder (AUC = 0.59, R2 = 4.3%, p < 0.0001). Time to conception showed moderate prognostic value (AUC = 0.56, R2 = 2.2%, p = 0.02): 49% (40/81) of those who took more than one year to conceive met morbidity criteria. Ethnicity also had an effect (AUC = 0.57, R2 = 2.4%, p = 0.07): 40% of White women. | Conclusions: Women with a history of mental health problems or previous losses may be at higher risk of psychological disorders one month after pregnancy loss. However, overall prognostic capacity was poor. All women should be considered at risk. Recommendations: Health professionals should be particularly attentive to the risk of morbidity in women with psychiatric history and previous losses. |

| Slot et al. * [41] | Sample: 298 women. Loss: 86% had experienced a pregnancy loss within the past 6 months. | The median age was 35 years (range 20–45). | Descriptive statistics, Mann–Whitney U test, and Chi-square test. | Women with primary recurrent pregnancy loss, compared to those with secondary recurrent loss, more often felt less self-confident, lacking a sense of purpose, having difficulty concentrating, and feeling restless. On the Perceived Stress Scale, women with primary recurrent loss more frequently reported being unable to control important matters. | Feelings of guilt and loss of control predominated in women with recurrent pregnancy loss. Recommendations: Addressing these specific feelings could help in treating the psychological aspects of recurrent pregnancy loss. |

| Mann et al. * [42] | Sample: 374 women. Women with and without pregnancy loss were generally quite similar in sociodemographic data. | In women with pregnancy loss, the mean age was 28.9 years (SD = 5.6), and in those with live births it was 28.6 years (SD = 5.6). | Bivariate linear regression and multiple regression. | The timing of follow-up did not predict either grief or depression, although women who responded by mail reported greater grief. Age was inversely related to grief and depression, while being White was associated with higher levels of both. Higher initial depression scores and a personal or family history of mental illness predicted greater depression at follow-up, whereas having more children was associated with fewer depressive symptoms. Religious attendance and perceived spirituality were linked to less grief: those who attended a few times per month scored 7.4 points lower on the grief scale, once per week 9.4 points lower, and two or more times 9.7 points lower compared to those who rarely or never attended. In multivariate analysis, initial depressive symptoms and history of mental illness predicted higher EPDS scores at follow-up, while age showed an inverse relationship. These three variables explained 64% of the variation in depressive symptoms. Similarly, grief, being White, age, and attending religious services at least a few times per month were significantly and inversely associated. Responding by mail was linked to greater grief. The model explained 57% of the variation in grief scores. Being White and self-reported spirituality were not significant and were excluded. | In multivariate linear regression models, depressive symptoms were significantly positively associated with initial depression scores and history of mental illness. Depression scores were significantly inversely associated with age. Increasing age also protected against grief after pregnancy loss, as did participation in organized religious activities. Future research should include larger samples and be conducted longitudinally. |

| Issakhanova et al. * [43] | Sample: 70 women with recurrent pregnancy loss and 78 control women. C.SD 5: A higher frequency of low educational level was observed in the control group, while university education was more prevalent in cases of recurrent pregnancy loss (p = 0.009). Loss: There was a significantly higher number of pregnancies (p < 0.001) and a lower number of live births (p < 0.001) in cases of recurrent loss. | Overall mean age was 34.8 ± 7.1 years; in women with recurrent pregnancy loss, 33.6 ± 7 years; and in controls, 35.7 ± 7 years (p = 0.07). | Descriptive statistics, Fisher’s exact test, Student’s t-test, Mann–Whitney U test, and multiple linear regression. | Recurrent pregnancy loss was associated with higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depression (p < 0.001), even after adjusting for age, ethnicity, BMI, and education. None of these variables (age, BMI, educational level, ethnicity) predicted the symptoms (p > 0.05). There were also no significant differences in BMI (p = 0.91), family income (p = 0.51), age at menarche (p = 0.22), or frequency of gynecological diseases (p = 0.54) between women with recurrent losses and the control group. | Psychological morbidity is common among women who have experienced pregnancy loss. The results show that Kazakh women with a history of recurrent miscarriages have higher levels of stress, depression, and anxiety compared to women who had a successful pregnancy. |

| Farren et al. ** [44] | Sample: 737 women with an early pregnancy loss (537 spontaneous miscarriages and 116 ectopic pregnancies) and 171 controls | Age not reported | Generalized linear mixed models. | At 1 month, women with losses had a higher risk of moderate/severe anxiety (unadjusted OR = 2.20, 95% CI: 1.18–4.51; adjusted OR = 2.14, 95% CI: 1.14–4.36) and of moderate/severe depression (unadjusted OR = 5.13, 95% CI: 1.56–31.72; adjusted OR = 3.88, 95% CI: 1.27–19.2) compared to healthy pregnancies. Each month, the odds decreased: PTSD 20% (OR = 0.80, 95% CI: 0.72–0.89), anxiety 31% (OR = 0.69, 95% CI: 0.50–0.94), and depression 13% (OR = 0.87, 95% CI: 0.53–1.44). A history of early loss or a new loss during the study increased the risk. In women with spontaneous miscarriage, the monthly risk decreased: PTSD 23% (OR = 0.77, 95% CI: 0.68–0.87), anxiety 35% (OR = 0.65, 95% CI: 0.44–0.94), and depression 34% (OR = 0.66, 95% CI: 0.32–1.35). In ectopic pregnancy, the monthly reduction was smaller: PTSD 16% (OR = 0.84, 95% CI: 0.69–1.03), anxiety 20% (OR = 0.80, 95% CI: 0.59–1.10), and depression 4% (OR = 0.96, 95% CI: 0.57–1.61). The wide confidence intervals limit strong comparisons, although the data suggest that the decrease after ectopic pregnancy is slower than after spontaneous miscarriage. | Although the prevalence of each disorder decreased over time, the observed proportions remained high nine months after early pregnancy loss (18% for post-traumatic stress, 17% for moderate-to-severe anxiety, 6% for moderate-to-severe depression). In viable pregnancies after one month, 13% of women reported moderate-to-severe anxiety and 2% reported moderate-to-severe depression. Prevalence was high both after spontaneous miscarriage and ectopic pregnancy; however, there is tentative evidence of a slower decrease following ectopic pregnancy. |

| Druget et al. * [45] | Sample: 28 Spanish women with the loss of one or both twins. C.SD 5: All had a partner. Half of the participants (n = 14) had higher education. Three-quarters (n = 20) had not had children, and 64.3% (n = 18) considered themselves to have access to social and family support. Loss: 34 of the initial 56 fetuses died. In the remaining five cases, death occurred after birth. For the 22 surviving fetuses, the mean gestational age at birth was 34.5 weeks. All were still alive at the time of the study assessments, which were carried out between 1 and 3 years after birth in monochorionic twin pregnancies (mean = 822 days, range: 376–1273 days). Clinical history: Half of the participants (n = 12) had previously suffered one or more miscarriages. A similar proportion (n = 12) reported a history of psychological or psychiatric problems, and six were receiving psychological treatment at the time of the study. | The mean age of the participants was 35.7 years (range: 25–43 years). | Descriptive statistics, Pearson and Spearman correlation, Student’s t-test, Mann–Whitney U test, and analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction. | Higher levels of grief were significantly and positively correlated with higher levels of state and trait anxiety, depressive symptoms, and post-traumatic stress. Similarly, scores on each subscale (Active Grief, Difficulty Coping, and Despair) were significantly and positively correlated with scores on the Hyperarousal subscale of the IES-R, scores on both STAI scales (state and trait anxiety), and total BDI scores (depression). A significant association was also observed between the Active Grief subscale and the Intrusion subscale of the IES-R, and between the Despair subscale and the total IES-R score. No association was found between the intensity of grief and the number of weeks of gestation at the time of loss, maternal age, or history of miscarriage. | The loss of a fetus during a multiple pregnancy is a relatively uncommon event whose unique characteristics make it a singular experience for the mother. The survival of a newborn and the difficulty of acknowledging the loss at both individual and social levels may complicate the grieving process and lead to the emergence of psychological symptoms. Therefore, it is crucial to recognize that these women have increased vulnerability to psychopathology and to identify the associated risk factors. |

| Kulathilaka et al. * [46] | Sample: 137 women who had experienced a spontaneous miscarriage and 137 with a viable pregnancy. C.SD 5: The majority were Sinhalese and Buddhist. Fifty-four (39.4%) women in the miscarriage group had ≥10 years of education, compared with 37 (27%) in the comparison group. Clinical: The period of amenorrhea was less than 12 weeks in most women with miscarriage (n = 89; 71.8%), compared with women in the comparison group (n = 33; 24.6%). | In the miscarriage group, the mean age was 30.39 years (SD = 6.38). The comparison group had a mean age of 28.79 years (SD = 6.26). | Student’s t-test, Chi-square test, and generalized linear models. | The prevalence of depression was 18.6% (95% CI: 11.51–25.77) after miscarriage and 9.5% (95% CI: 4.52–14.46) in the comparison group. The relative risk (RR) of depression was 1.96 (95% CI: 1.04–3.73), but after adjusting for age and postpartum status it was no longer significant (adjusted RR = 1.42, 95% CI: 0.65–3.07; p = 0.38). Moderate-to-severe depression was detected in 16.9% (20 women) with miscarriage and 11.8% (16 women) in the comparison group. Complicated grief had a prevalence of 54.7% (95% CI: 46.3–63.18). 41.5% (49 women) did not present depression or grief. Among the 64 with grief, 26.6% (17 women) also had depression, while only 9.3% (5 women) showed depression without grief. | The relative risk of developing a depressive episode after miscarriage was not significantly higher compared to pregnant women after accounting for age and the period of amenorrhea. Nearly half of the women developed complicated grief following miscarriage. Among these, a significant proportion also presented features of depressive disorder. |