PCOS Symptoms and Quality of Life: Links to Anxiety and Self-Esteem Among Women with PCOS in Slovakia

Abstract

1. Introduction

Research Problem, Objectives and Research Questions

- To identify the PCOS symptoms that women with the condition perceive as the most limiting in their daily lives.

- To clarify the relationships between general quality of life, Anxiety, and self-esteem in women diagnosed with PCOS.

- To examine the relationships between the quality of life related to PCOS symptoms experienced and the general quality of life in women affected by the syndrome.

2. Results

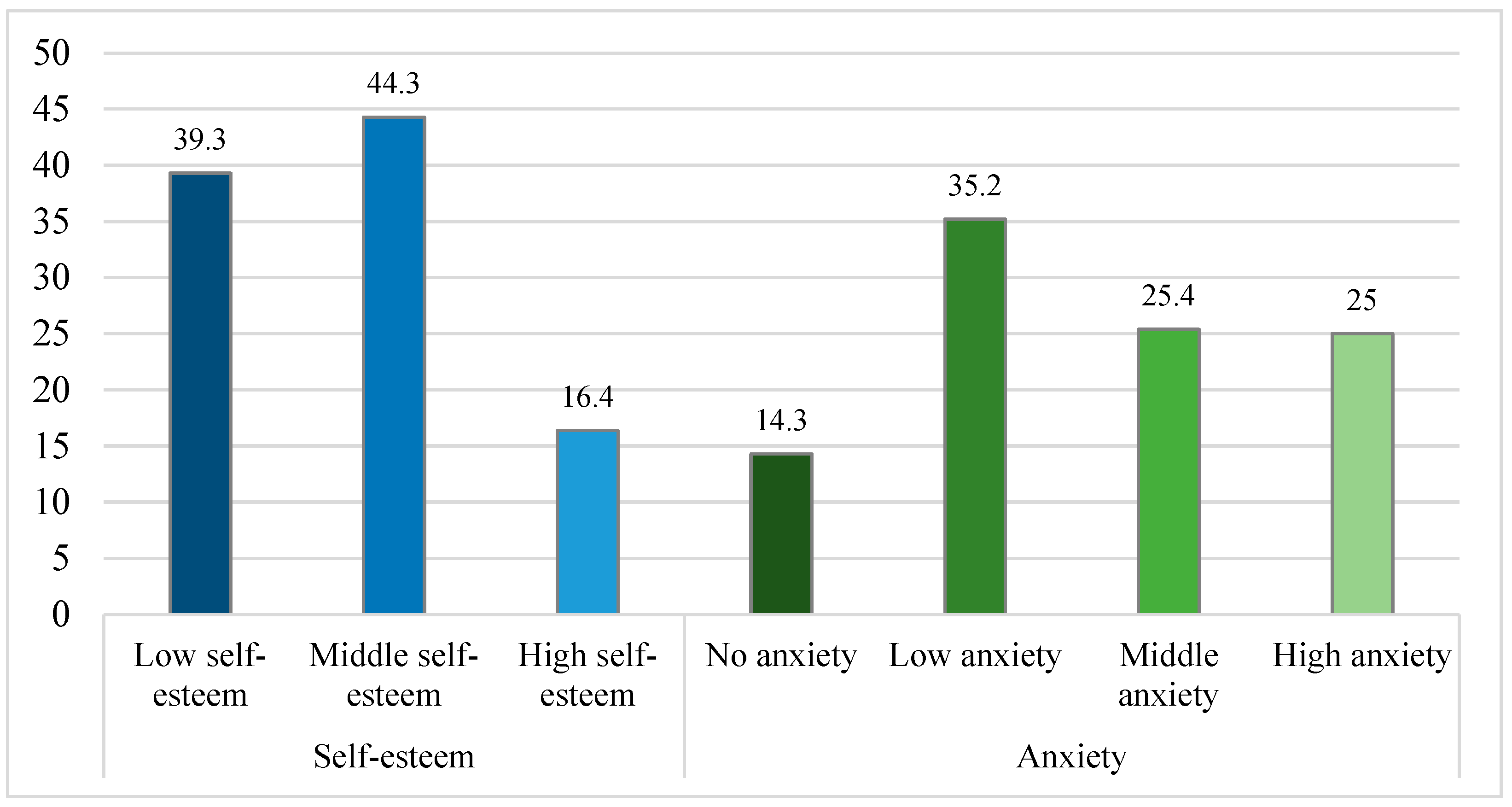

2.1. Variables Description

2.2. Statistical Testing

3. Discussion

Limitations

4. Methods

4.1. Participants and the Study Design

4.2. Instruments and Variables

4.3. Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| PCOS | Polycystic Ovary Syndrome |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- La Rosa, V.L.; Giannella, L.; Sapia, F.; Laganà, A.S.; Calagna, G.; Ghezzi, F.; Ferrero, S. Psychological Impact of Gynecological Diseases: The Importance of a Multidisciplinary Approach. Ital. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2018, 30, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jafari, K.; Tajik, N.; Moini, A.; SeyedAlinaghi, S.; Abiri, A. Metabolic mediators of the overweight’s effect on infertility in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeks, A.A.; Gibson-Helm, M.; Moran, L.J. Anxiety and Depression in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Comprehensive Investigation. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 93, 2421–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teede, H.J.; Deeks, A.; Moran, L. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Complex Condition with Psychological, Reproductive and Metabolic Manifestations That Impacts on Health across the Lifespan. BMC Med. 2010, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teede, H.J.; Misso, M.L.; Costello, M.F.; Dokras, A.; Laven, J.; Moran, L.; Stener-Victorin, E.; Bhattacharya, S.; Norman, R.J.; Franks, S. Recommendations from the 2023 International Evidence-based Guideline for the Assessment and Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 2023, 120, 767–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karjula, S.; Arffman, R.K.; Morin-Papunen, L.; Franks, S.; Järvelin, M.R.; Tapanainen, J.S.; Miettunen, J.; Piltonen, T.T. A population-based follow-up study shows high psychosis risk in women with PCOS. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2022, 25, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barth, C.; Villringer, A.; Sacher, J. Sex Hormones Affect Neurotransmitters and Shape the Adult Female Brain during Hormonal Transition Periods. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, Z.B.; Faramarzi, M.; Khodakarami, B. Measures of Health-Related Quality of Life in PCOS Women: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Womens Health 2018, 10, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligocka, D.; Czyzyk, A.; Skowronska, D. Quality of Life of Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Medicina 2024, 60, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Açmaz, G.; Yılmaz, N.; Kutlu, M. Level of Anxiety, Depression, Self-Esteem, Social Anxiety, and Quality of Life among the Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 851815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dokras, A.; Stener-Victorin, E.; Yildiz, B.O.; Li, R.; Ottey, S.; Shah, D.; Epperson, N.; Teede, H. Androgen Excess-Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society: Position Statement on Depression, Anxiety, Quality of Life, and Eating Disorders in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 105, 888–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkheyr, A.; Alkhayyat, W.; Alajmi, N. Self Esteem and Body Image Satisfaction in Women with PCOS in the Middle East: Cross Sectional Social Media Study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0301707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Niet, J.E.; de Koning, C.M.; Pastoor, H.; Duivenvoorden, H.J.; Valkenburg, O.; Ramakers, M.J.; Passchier, J.; de Klerk, C.; Laven, J.S. Psychological Well-Being and Sexarche in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Hum. Reprod. 2010, 25, 1497–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazarganipour, F.; Ziaei, S.; Montazeri, A.; Foroozanfard, F.; Kazemnejad, A.; Faghihzadeh, S. Body Image Satisfaction and Self-Esteem Status among the Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Iranian J. Reprod. Med. 2013, 11, 829–836. [Google Scholar]

- Deeks, A.A.; Gibson-Helm, M.E.; Paul, E.; Teede, H.J. Is Having Polycystic Ovary Syndrome a Predictor of Poor Psychological Function Including Anxiety and Depression? Hum. Reprod. 2011, 26, 1399–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolhe, J.V.; Chhipa, A.S.; Butani, S.; Chavda, V.; Patel, S.S. PCOS and Depression: Common Links and Potential Targets. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 29, 3106–3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, C.T.; Griggs, J.; O’Brien, S.; Moran, L. Increased Prevalence of Eating Disorders, Low Self-Esteem, and Psychological Distress in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Community-Based Cohort Study. Fertil. Steril. 2019, 112, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooney, L.G.; Lee, I.; Sammel, M.D.; Dokras, A. High Prevalence of Moderate and Severe Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 1075–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, N.; Ismail, M.S. Psychological Impact on Mental Health and Well-Being in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): A Narrative Review. Int. J. Sci. Adv. 2024, 5, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowinska, B.; Suchta, J.; Kedzia, W. Disparate Relationship of Sexual Satisfaction, Self-Esteem, Anxiety, and Depression with Endocrine Profiles of Women with or without PCOS. Reprod. Sci. 2020, 27, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, M.; Khan, R.; Iqbal, S. Frequency of Generalized Anxiety Disorders in Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Pak. Armed Forces Med. J. 2021, 71, 1455–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liu, X.; Zhu, S.; Lei, J. Experience of Mental Health in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Descriptive Phenomenological Study. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2023, 44, 2218987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeratibharat, S.; Somjit, M.; Vacharaksa, A. Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) and Associated Factors in a Quaternary Hospital in Thailand: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, G.; Cera, N.; Pignatelli, S. Psychological Symptoms and Brain Activity Alterations in Women with PCOS and Their Relation to the Reduced Quality of Life: A Narrative Review. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2024, 47, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomami, M.B.; Ramezani Tehrani, F.; Hashemi, S.; Farahmand, M.; Azizi, F. Of PCOS Symptoms, Hirsutism Has the Most Significant Impact on the Quality of Life of Iranian Women. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnard, L.; Ferriday, D.; Guenther, N.; Strauss, B.; Balen, A.H.; Dye, L. Quality of Life and Psychological Well-Being in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Hum. Reprod. 2007, 22, 2279–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, S.; Rizwani, G.H.; Fatima, S.; Shareef, H.; Anser, H.; Jamil, S. Relative Risks Associated with Women’s Quality of Life Suffering from Metabolic, Reproductive, and Psychological Complications of PCOS: A Comparative Cross-Sectional Study. Res. Sq. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCook, J.G.; Reame, N.E.; Thatcher, S.S. Health-Related Quality of Life Issues in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2005, 34, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.L.; Benes, K.; Clark, T.L.; Denham, R.; Holder, M.G.; Haynes, T.J.; Mulgrew, N.C.; Shepherd, K.E.; Wilkinson, V.H.; Singh, M. Health-Related Quality of Life Among Adolescents with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2011, 40, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumarapeli, V.; Sullivan, E.A.; Bowtell, P.; Culbert, J.; Lonie, S.; Higgins, R.; Knight, A.; Carson, A.; Zhang, A.; Norman, R. Health-Related Quality of Life and Psychological Distress in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Hidden Facet in South Asian Women. BJOG 2010, 118, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wu, Y.; Mprah, R.; Wang, S. COVID-19 and Persistent Symptoms: Implications for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Its Management. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1434331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torge, D.; Bernardi, S.; Arcangeli, M.; Bianchi, S. Histopathological Features of SARS-CoV-2 in Extrapulmonary Organ Infection: A Systematic Review of Literature. Pathogens 2022, 11, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Mohanty, S.; Kaduluri, C.S.; Bhatt, G.; Ninama, P.; Bapat, N. A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study to Analyse the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Lifestyle and Manifestations of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome among Clinically Diagnosed Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome Cases Aged 15–49 Years. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2022, 10, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson-Helm, M.; Teede, H.J.; Lohfeld, L.; Aziz, R.; Boyle, J.; Moran, L.J.; Joham, A.E. Delayed Diagnosis and a Lack of Information Associated with Dissatisfaction in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 102, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-Y.; Park, E.-Y. The Rasch Analysis of Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale in Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferenčáková, Ľ.; Kubašovská, K. Generalizovaná Úzkostná Porucha—Štandardné Diagnostické a Terapeutické Postupy; Ministerstvo Zdravotníctva Slovenskej Republiky: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vatehová, M.; Vateha, J. Manažment Ošetrovateľskej Starostlivosti o Pacientov s Vybranými Chronickými Chorobami; Osveta: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Group. Slovak_WHOQOL-BREF. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/whoqol/whoqol-bref/docs/default-source/publishing-policies/whoqol-bref/slovak-whoqol-bref (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Cronin, L.; Guyatt, G.; Griffith, L.; Wong, E.; Azziz, R.; Futterweit, W.; Cook, D.; Dunaif, A. Development of a Health-Related Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (PCOSQ) for Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1998, 83, 1976–1987. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, G.; Benes, K.; Clark, T.; Denham, R.; Holder, M.; Haynes, T.; Mulgrew, N.; Shepherd, K.; Wilkinson, V.; Singh, M.; et al. The Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Health-Related Quality of Life Questionnaire (PCOSQ): A Validation. Hum. Reprod. 2004, 19, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health of the Slovak Republic. Comprehensive Management of Adolescent and Adult Patients with Generalized Anxiety Disorder (Standard Diagnostic and Therapeutic Guideline No. 098/1-6/2020). Collect. Laws Slovak Repub. 2020. Available online: https://www.health.gov.sk/Zdroje?/Sources/dokumenty/SDTP/standardy/1-6-2020/098_KP_Komplexny_manazment_adolescentneho_a_dospeleho_pacienta_s_generalizovanou_uzkostnou_poruchou.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Tomšík, R.; Rajčániová, E.; Ferenčíková, P. Prežívanie úzkosti, stresu, osamelosti a well-being rodičov počas prvej a druhej vlny pandémie koronavírusu na Slovensku. Disk. Psychol. 2021, 3, 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Halama, P.; Bieščad, M. Psychometrická Analýza Rosenbergovej Škály Sebahodnotenia s Použitím Metód Klasickej Teórie Testov (CTT) a Teórie Odpovede na Položku (IRT). Ceskoslov. Psychol. 2006, 50, 569–583. [Google Scholar]

| Other Chronic Conditions | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Thyroid disorders (e.g., hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism) | 48 | 20 |

| Mental health disorders (e.g., depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder) | 36 | 15 |

| Dermatological conditions (e.g., psoriasis, seborrhoea, atopic dermatitis) | 34 | 14.17 |

| Chronic respiratory conditions (e.g., asthma, chronic rhinitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) | 21 | 8.75 |

| Chronic digestive disorders and intolerances (e.g., Crohn’s disease, IBS, celiac disease, lactose intolerance) | 21 | 8.75 |

| Metabolic disorders (e.g., type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance, Gilbert’s syndrome) | 20 | 8.33 |

| Cardiovascular diseases (e.g., hypertension, angina pectoris, chronic ischemic heart disease) | 20 | 8.33 |

| AM | SD | Min–Max | |

|---|---|---|---|

| QoL-PCOS—total | 3.5 | 1.1 | 1.2–6.5 |

| Emotions | 3.5 | 1.2 | 1–7 |

| Body hair | 3.7 | 2 | 1–7 |

| Weight | 3.4 | 1.9 | 1–7 |

| Infertility | 2.8 | 1.5 | 1–7 |

| Menstrual problems | 3.3 | 1.3 | 1–7 |

| Acne | 4.4 | 1.8 | 1–7 |

| Self-esteem | 16.3 | 5.6 | 0–30 |

| Anxiety | 10.3 | 5.3 | 0–21 |

| QoL-WHO—total | 16.8 | 6.3–98.5 | |

| Physical health | 71.4 | 3.6–100 | |

| Psychological health | 45.8 | 0–95.8 | |

| Social relations | 61.9 | 66.7 | 0–100 |

| Environment | 59.9 | 56.3 | 0–100 |

| QoL-WHO | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QoL-PCOS | Physical Health | Psychological Health | Social Relationships | Environment | QoL-WHO Total |

| QoL-PCOS—Total | 0.648 ** | 0.523 ** | 0.377 ** | 0.457 ** | 0.605 ** |

| Emotions | 0.573 ** | 0.524 ** | 0.318 ** | 0.409 ** | 0.558 ** |

| Body hair | 0.590 ** | 0.327 ** | 0.235 ** | 0.256 ** | 0.421 ** |

| Weight | 0.461 ** | 0.534 ** | 0.360 ** | 0.397 ** | 0.535 ** |

| Infertility | 0.258 ** | 0.246 ** | 0.105 | 0.156 b | 0.228 ** |

| Menstrual problems | 0.492 ** | 0.337 ** | 0.227 ** | 0.377 ** | 0.418 ** |

| Acne | 0.341 ** | 0.307 ** | 0.279 ** | 0.355 ** | 0.386 ** |

| QoL Variables | Anxiety | Self-Esteem |

|---|---|---|

| QoL-PCOS—Total | −0.453 ** | 0.418 ** |

| Emotions | −0.516 ** | 0.432 ** |

| Body hair | −0.314 ** | 0.290 ** |

| Weight | −0.290 ** | 0.379 ** |

| Infertility | −0.208 ** | 0.189 ** |

| Menstrual problems | −0.369 ** | 0.262 ** |

| Acne | −0.297 ** | 0.259 ** |

| QoL-WHO—Total | −0.527 ** | 0.655 ** |

| Physical health | −0.516 ** | 0.542 ** |

| Psychological health | −0.524 ** | 0.737 ** |

| Social relationships | −0.269 ** | 0.408 ** |

| Environment | −0.409 ** | 0.460 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Górna, M.; Čamarová, N.; Rojková, Z.; Slebodová, P. PCOS Symptoms and Quality of Life: Links to Anxiety and Self-Esteem Among Women with PCOS in Slovakia. Women 2025, 5, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5030035

Górna M, Čamarová N, Rojková Z, Slebodová P. PCOS Symptoms and Quality of Life: Links to Anxiety and Self-Esteem Among Women with PCOS in Slovakia. Women. 2025; 5(3):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5030035

Chicago/Turabian StyleGórna, Marta, Natália Čamarová, Zuzana Rojková, and Patrícia Slebodová. 2025. "PCOS Symptoms and Quality of Life: Links to Anxiety and Self-Esteem Among Women with PCOS in Slovakia" Women 5, no. 3: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5030035

APA StyleGórna, M., Čamarová, N., Rojková, Z., & Slebodová, P. (2025). PCOS Symptoms and Quality of Life: Links to Anxiety and Self-Esteem Among Women with PCOS in Slovakia. Women, 5(3), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5030035