Abstract

Depression and anxiety are the most prevalent mental health concerns among college students. In addition to the typical college stressors, Hispanic students may experience minority status stress associated with their membership in a socially stigmatized ethnic and cultural group. Ethnic minority status stress has been positively associated with psychological distress. Therefore, this study examined, among Hispanic college students, (a) gender differences in the associations of ethnic minority status stress and social support to depression and anxiety symptoms, (b) if social support buffered the association of minority stress with depression and anxiety symptoms, and (c) if the social support moderation effect differed by gender. The results indicated that the negative association of social support to depression symptoms was stronger for women than men and that social support buffered the association of ethnic minority status stress to depression symptoms only for women. The negative association of minority status stress to depression symptoms was statistically significant only for women who reported lower levels of social support. No gender or social support moderation effects were observed in relation to anxiety symptoms for women or men. The results highlight the importance of social support in ameliorating the potential impact of ethnic minority status stress on psychological distress among Hispanic college women.

1. Introduction

Hispanics are one of the fastest growing ethnic groups in the United States (U.S.) [1]. Consistent with their growth in the population, from 2000 to 2020, the number of Hispanic students attending four-year colleges increased by 287% (from 620,000 to 2.4 million) compared to an overall college enrollment growth of 50% [2]. Despite their increased participation in higher education, Hispanics continue to experience disparities in college degree attainment. In 2021, 23% of Hispanic 25- to 29-year-olds were bachelor’s degree recipients, while the same was true for 45% of White American and 72% of Asian American young adults [2]. Because the number of Hispanic college students will likely continue to grow [1], research is needed regarding factors that contribute to their academic success.

Depression and anxiety are the most prevalent concerns among students who seek help from mental health services on university campuses [3]. The results of the 2024 American College Health Association national survey revealed that a relatively large number of undergraduate students reported that they had been treated for or diagnosed with depression (27%) or anxiety (31%) symptoms in their lifetime and that a larger proportion of women than men reported both anxiety (40% vs. 18%) and depression (29% vs. 14%) symptoms, respectively [4]. In addition, the results from the survey revealed that students’ depression (56%) and anxiety (48%) symptoms negatively impacted their academic performance [4]. While there are mixed findings regarding differences in psychological distress among students from different racial and ethnic backgrounds [5], the results from multi-campus national studies in the U.S. revealed higher levels of depression [6] and anxiety [7] symptoms among Hispanic students compared to their White peers. Furthermore, in a national sample of adolescents and young adults, Black, Hispanic, and Asian American women reported higher levels of depression symptoms than their male counterparts and women from other ethnic groups [8]. Consistent with findings in the general college population [9], higher levels of psychological distress have been associated with lower grades and lower intentions to persist to graduation among Hispanic college students [10]. These findings suggest that it is important to further examine factors that contribute to the psychological health of Hispanic college women and men, which in turn may impact their academic success.

1.1. Ethnic Minority Status Stress

In addition to the typical academic, social, and financial stressors associated with college life, Hispanic students in the U.S. may experience minority status stress, which refers to the psychological strain associated with negative events individuals attribute to their membership in a stigmatized social group. Ethnic minority status stress captures several dimensions, including campus social climate (feeling unwanted or devalued due to their ethnicity), discrimination (personal experiences of ethnic prejudice and discrimination), within-group pressures (expectations to conform with the traditional customs and behavior of their own ethnic group), and academic achievement stress (concerns about lack of ability and/or preparation to meet academic demands relative to non-ethnic minority peers) [11,12].

Research findings with mixed groups of ethnically diverse college students indicated that when accounting for general college stress, ethnic minority status stress was positively associated with psychological distress [13] and negatively related to college persistence attitudes [14]. Similarly, a few studies on Hispanic college women and men indicated that ethnic minority status stress global scores were uniquely and positively associated with depression symptoms [10,15]. In turn, depression symptoms mediated the negative association of ethnic minority status stress with college persistence intentions among Hispanic college women [10]. Taken together, these findings suggest that the psychological distress associated with ethnic minority status stress may be particularly detrimental to the college success of Hispanic women. Therefore, further research regarding factors that may buffer the relation of ethnic minority status stress with negative psychological outcomes among college women and men is needed to inform psychological interventions with Hispanic college students.

No studies were found that examined gender differences in the association of ethnic minority status stress with psychological distress. However, a few studies that examined gender differences in the association of discrimination, a component of minority status stress, with psychological distress revealed mixed findings. One study reported that the negative association of discrimination with depression symptoms was stronger for Hispanic adolescent boys compared to girls [16]. However, other studies found that among high school [17] and young adults [18] of Hispanic descent, gender did not moderate the association of ethnic discrimination with depression symptoms. Therefore, this study examined to what extent gender moderates the association of minority status stress with depression and anxiety symptoms among Hispanic college students. Because of the increased incidence of depression and anxiety symptoms among Hispanic college women compared to their male peers [4], we also examined to what extent social support differentially buffered the association of ethnic minority status stress with depression and anxiety symptoms among Hispanic college women and men.

1.2. Social Support

Social support refers to individuals’ perceptions of the quantity and quality of emotional validation and instrumental assistance they receive from people in their lives, including family and friends. The stress-buffering model suggests that social support may mitigate the relationship between stress and psychological distress by reducing feelings of loneliness and promoting self-esteem, which in turn enables people to cope more effectively with the stressors they encounter [19]. To test the stress-buffering model, researchers have examined the direct relation of social support with psychological distress and well-being and to what extent social support buffers the relation of stress with psychological outcomes.

The link between social support with psychological functioning has been well established. The results of a recent quantitative synthesis of 60 independent meta-analyses yielded a robust average effect size for the negative association of social support with depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms. Furthermore, moderation analyses indicated that these effects were consistent in studies with participants from different ages and cultural backgrounds and studies that assessed social support globally or from specific sources (e.g., family, friends, and significant others) [20]. In the meta-analysis, researchers did not examine gender as a potential moderator [20]. However, in several studies, the strength of the association of social support with psychological distress differed for men and women [21,22,23,24,25]

Researchers have proposed that, consistent with societal and cultural gender role expectations, when coping with stressful situations, women may be more likely to turn to others for help and support while men may be more inclined to address difficulties independently [26]. Consistent with this view, in an analog study with college students in Canada, more women than men indicated that they would seek help from family and friends to cope with several potentially stressful scenarios they were presented with [27]. Similarly, in studies with European and European American college students [28,29] and adults [21,22,23], women reported greater quality and quantity of social support than men. However, studies that examined gender differences in the association of social support with depression symptoms have yielded mixed findings. Several studies with emerging adults [23,24] and adults across the life span [21,22] revealed a stronger negative association of social support with depression symptoms among women than men. In contrast, the results of a meta-analytic review of studies with children and adolescents reported no gender differences in the association of social support with depression symptoms [25]. Therefore, further research is needed to examine to what extent gender moderates the association of social support to psychological distress among college students.

Studies that have examined the role of social support in the relation of various types of stressors with depression and anxiety symptoms have also yielded mixed findings. Two studies with Hispanic college students revealed that social support buffered the association of acculturative stress [30] and general stress [31] with anxiety symptoms. Perceived quality or availability of global social support also buffered the association of general stress with depression symptoms among Hispanic American college students [31] and college students in Mexico [32]. However, two studies with Hispanic college students and community adults in the U.S. revealed that social support did not attenuate the positive correlation between depression symptoms and college stress [33] or discrimination stress [34], and a third study indicated no social support moderation in the association of discrimination stress with anxiety symptoms among Asian American adults [35].

The only study that examined the three-way interaction of stress, social support, and gender found that, among high school students in China, social support from friends buffered the positive association of general life stress with depression symptoms for girls only. Among boys, general life stress was positively associated with depression symptoms regardless of differences in social support [36]. Given the mixed findings in previous research regarding gender differences in the association of social support with psychological distress among adolescents [25] and emerging adults [23,24], and the relatively higher levels of depression and anxiety symptoms among Hispanic college women than men [4], this study examined if the moderating effect of social support in the association of ethnic minority status stress with psychological distress differed for Hispanic college women and men.

1.3. The Present Study

Research findings indicated that depression symptoms are positively associated with ethnic minority status stress and negatively associated with social support, and that social support may attenuate the association of stress from various sources with both depression and anxiety symptoms. Previous findings also suggest that women may be more likely than men to seek and utilize social support in difficult times and that the association of social support with depression symptoms may be stronger among adult women than men. However, less is known about the role that social support may play in the relationship between ethnic minority status stress and depression and anxiety symptoms. Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to examine the following research questions among Hispanic college students in the U.S.: (1) Is ethnic minority status stress positively associated with depression and anxiety symptoms when controlling for general college stress and social support? (2) Does gender buffer the associations of ethnic minority status stress and social support with depression and anxiety symptoms (two-way interactions)? (3) Does social support buffer the association of ethnic minority status stress to depression and anxiety symptoms (two-way interaction), and does this moderation effect differ by gender (three-way interaction)?

We expected that ethnic minority status stress would be positively associated with depression and anxiety symptoms and that social support would be negatively associated with depression and anxiety symptoms when controlling for all other variables in the model. Because of the mixed findings in previous research, no hypotheses were formulated regarding gender differences in the association of social support with psychological distress, to what extent social support would buffer the association of ethnic minority status stress with depression or anxiety symptoms, and if the social support moderation effect would differ by gender.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were 797 Hispanic students in a major research university in the Southwest U.S. that has been recognized as a Hispanic-serving institution (i.e., at least 25% of the student body is of Hispanic descent). Most participants (80%) were born in the U.S. and reported that their family of origin was from Mexico (69%), El Salvador (9%), or other Latin American countries (21%, e.g., Puerto Rico, Colombia, Nicaragua, and Venezuela). Students ranged in age from 18 to 29 years old with a mean age of 21 years old (SD = 2.47), 514 (64.5%) students identified as women and 283 (35.5%) as men, and 20% were freshmen, 27% sophomores, 33% juniors, and 20% seniors. Approximately half of the students (391, 49%) described their family of origin as middle class or above, and the other half (406, 51%) as working class or below. Students whose professors offered extra class credit for research participation accessed the study materials on their own through an online system used to recruit and manage research participation. Undergraduate students from all majors in the university had access to the research participation online system. Participation was voluntary and anonymous; it took about 30 min for students to complete the study’s online questionnaires, which students completed on their own time. None of the authors of the study taught courses that provided extra credit for study participation. The university’s institutional review committee approved the study’s research protocols.

2.2. Instruments

Demographic Questionnaire. This survey included questions about participants’ gender, age, place of birth of parents and self, social class of family of origin, and student’s year in college.

College Stress Scale (CSS). The CSS includes 18 items regarding potentially stressful college-related experiences in the academic, social, emotional, and financial domains [37]. Students rated the stressfulness of each item on a 6-point Likert scale that ranged from 0 “does not apply to me” to 5 “extremely stressful”. A college stress score was obtained by averaging the scale’s 18 items. Cronbach’s alpha internal reliability coefficient for study participants’ responses to the total CSS scores was 0.91.

Minority Status Stress Scale (MSSS). A 22-item version of the MSSS [11] used previously in ethnically diverse college campuses [10,37] was used to measure four domains of ethnic minority status stress: social climate stress, academic achievement stress, discrimination stress, and within-group stress. Participants rated the MSSS items on a 6-point Likert scale from 0 “does not apply” to 5 “extremely stressful.” A total minority status stress score was calculated by averaging scores in the scale’s 22 items. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the total MSSS scores was 0.93.

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS). The MSPSS includes 12 items that measure perceptions of adequacy of social support received from three sources: family, friends, and significant others [38]. Participants rated the MSPSS items on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 “very strongly disagree” to 7 “very strongly agree”. A total social support score was calculated by averaging participants’ responses to the 12 items, with higher scores indicating higher levels of social support adequacy. Cronbach’s alpha for study participants’ total MSPSS scale scores was 0.93.

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). The PHQ-9 includes nine questions about participants’ feelings and symptoms of depression during the previous two weeks [39]. Participants rated the PHQ-9 items on a 4-point Likert scale that ranged from 0 “Not at all” to 3 “Nearly every day”. Total summary scores could range from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating more severe depression symptoms. Cronbach’s alpha internal reliability coefficient for participants’ responses to the PHQ-9 items was 0.90.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 scale (GAD-7). The seven GAD-7 [40] items assess generalized anxiety disorder symptoms’ frequency on a 4-point Likert scale that ranges from 0 “not at all” to 3 “nearly every day”. Total sum scores could range from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating higher levels of anxiety symptoms. Cronbach’s alpha internal reliability coefficient for participants’ responses to the GAD-7 items was 0.87.

3. Analysis and Results

Bivariate correlations, multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA), and hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to examine the study’s research questions. Statistical analyses were conducted using the IBM SPSS program Version 30.

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

Values for skewness (−0.10 to 1.03) and kurtosis (−0.52 to 0.69) for the study’s two criterion variables (depression and anxiety symptoms) and three predictor variables (college stress, ethnic minority status stress, and social support) were within acceptable ranges (−2 to +2) for the data to be considered normally distributed [41]. However, the results of the Shapiro–Wilk test for each of the five variables were statistically significant, which indicated that the distributions deviated from normality. Because the analysis of regression models is considered robust with respect to violations of the normality assumption [42], we continued with the planned analysis despite the mixed findings regarding normality. The results of bivariate correlational analysis, displayed in Table 1, indicated that the three predictors, college stress, minority status stress, and social support, were correlated with both depression and anxiety symptoms in the expected direction.

Table 1.

Correlations, means, and standard deviations for predictor and criterion variables.

The results of bivariate correlation analyses indicated that age and year in college were not associated with either depression (r = 0.01, p > 0.05 and r = −0.04, p > 0.05) or anxiety (r = −0.04, p > 0.05 and r = 0.03, p > 0.05) symptoms. A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) conducted to examine the association of gender (1 = male, 2 = female) and social class (1 = working class or poor, 2 = middle class or higher) with depression and anxiety symptoms showed that there was a significant multivariate effect for both gender (Pillai’s Trace = 0.29, F (2, 792) = 160.05, p < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.29) and social class (Pillai’s Trace = 0.009, F (2, 792) = 3.56, p < 0.03; partial η2 = 0.009). Follow-up univariate tests showed statistically significant gender differences in both depression F (1, 793) = 15.09; p < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.02) and anxiety F (1, 793) = 101.44; p < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.11) symptoms. Women reported higher levels of depression symptoms (M = 9.94 SD = 7.19) than men (M = 7.91, SD = 6.73), and men reported higher levels of anxiety symptoms (M = 6.68, SD = 5.29) than women (M = 3.31, SD = 4.04).

Regarding social class, follow-up univariate tests showed statistically significant differences only for depression symptoms (F (1, 793) = 7.14; p = 0.008; partial η2 = 0.01). Students who described their family of origin as working class or lower reported higher levels of depression symptoms (M = 8.55, SD = 6.89) than students who described their family of origin as middle-class or higher (M = 9.90, SD = 7.24). Follow-up univariate tests indicated that social class differences for anxiety symptoms were not statistically significant (F (1, 793) = 3.27; p = 0.71; partial η2 = 0.004) (working class/lower M = 4.79, SD = 4.97; middle class/higher M= 4.24, SD = 4.62). Therefore, gender, social class, and general college stress were included as control variables in the regression analyses predicting depression symptoms. However, only gender and college stress were included as control variables in the regression analyses predicting anxiety symptoms.

3.2. Minority Status Stress, Social Support, and Gender: Direct and Moderated Associations

Two four-step hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to examine the study’s three research questions. Steps 1-3 of each regression examined the collective and unique association of minority status stress and social support with depression symptoms (regression #1 controlling for gender, social class, general college stress, and social support) and anxiety symptoms (regression #2 controlling for gender, general college stress, and social support). In Step 4 of each regression, the three two-way interaction terms (minority status stress by gender, social support by gender, minority stress by social support), and the three-way interaction term (minority stress by social support by gender) were examined [43]. To interpret statistically significant moderation effects, the simple slopes of the association of predictors with their respective outcome variables were plotted for higher and lower levels (one standard deviation above/below the mean) of the moderator variable [43].

Tolerance values below 0.2 and variance inflation factors (VIFs) greater than 10 are cause for concern regarding multicollinearity [41]. In Step 3 of each regression model (last step before the interaction terms were entered), the tolerance statistics for the predictor variables for depression and anxiety were above 0.2 (range 0.72 to 0.97), and the VIF values in the models for depression (range 1.00 to 1.41) and anxiety (range 1.00 to 1.39) were all below 10. Therefore, multicollinearity among the predictor variables was not a problem. To further prevent multicollinearity, predictor variables were standardized before calculating the interaction terms and conducting the regression analyses.

Depression Symptoms. The results of the first four-step hierarchical regression analysis, displayed in Table 2, indicated that ethnic minority status stress, entered in Step 2, contributed unique variance to depression symptoms (ΔR2 = 0.31, ΔR2 = 0.03, p < 0.001). Social support, entered in Step 3, also contributed unique variance to depression symptoms (ΔR2 = 0.36, ΔR2 = 0.05, p < 0.001). Inspection of the beta coefficients in Step 3 showed that when considering all variables in the model, general college stress, ethnic minority status stress, and social support contributed unique variance to depression symptoms in the expected direction. The change in R2 from Step 3 to Step 4, where the interaction terms were entered, was statistically significant (ΔR2 = 0.37, ΔR2 = 0.01, p < 0.01). Inspection of the beta coefficients in Step 4 showed that only the two-way interaction of social support by gender and the three-way interaction of minority stress by social support and gender were statistically significant. The association of ethnic minority status stress with depression symptoms was not moderated by either gender or social support.

Table 2.

Hierarchical regression analyses: ethnic minority status stress, social support, and gender predicting depression and anxiety symptoms.

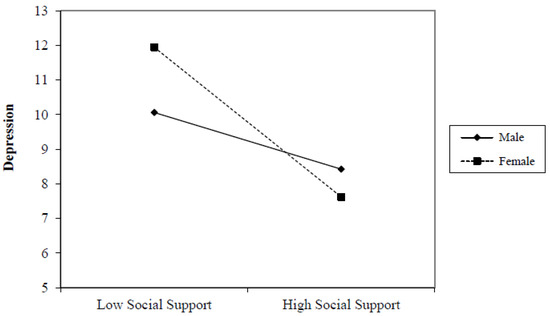

The plot depicting the two-way interaction of gender in the association of social support to depression symptoms is displayed in Figure 1. The results of slope analyses indicated that social support was negatively associated with depression symptoms for both gender groups; however, the negative association was stronger for women (slope = −2.160; t = −3.67, p < 0.001) compared to men (slope = −0.82; t = −2.48, p < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Gender moderates the association of social support with depression symptoms.

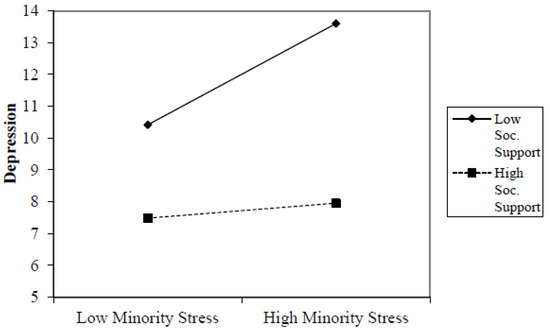

The statistically significant three-way interaction suggested that the moderation effect of social support on the association of ethnic minority status stress with depression symptoms differed for men and women. Two follow-up 2-step hierarchical regression analyses predicting depression symptoms were conducted to examine the two-way interaction between ethnic minority status stress and social support for each gender group separately. The results, displayed in Table 2, indicated that the change in R2 from Step 1 (which included the control, predictor, and moderator variables in the model) to Step 2 (in which the two-way ethnic minority status stress by social support interaction term was entered) was statistically significant in the regression for women (ΔR2 = 0.01, p < 0.01, β = −0.095, p < 0.01) but not in the regression for men (ΔR2 = 0.002, p > 0.05, β = 0.04, p > 0.05), meaning that the moderation effect was significant only for college women. The plot depicting the interaction effect for women is displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Social support moderates the association of minority status stress with depression symptoms among women.

The results of slope analyses indicated that ethnic minority status stress was positively associated with depression symptoms only for women who reported lower levels of social support (slope = 1.59; t = 4.27, p < 0.001). For women who reported higher levels of social support, the association of ethnic minority status stress with depression symptoms was not statistically significant (slope = 0.23; t = 0.60 p > 0.05). That is, higher levels of social support buffered the association of ethnic minority status stress to depression symptoms only among Hispanic college women.

Anxiety Symptoms. The results of the second four-step hierarchical regression analysis, also displayed in Table 2, indicated that when controlling for college stress and gender, ethnic minority status stress (R2 = 0.29, ΔR2 = 0.004, p < 0.01) entered in Step 2 and social support (R2 = 0.29, ΔR2 = 0.004, p < 0.01) entered in Step 3 contributed unique variance to anxiety symptoms. Inspection of the beta coefficients in Step 3 showed that when considering all the variables in the model, gender, college stress, and social support contributed unique variance to anxiety symptoms in the expected direction. However, with social support included in the model, ethnic minority status stress was no longer uniquely associated with anxiety symptoms. The change in R2 from Step 3 to Step 4, where the interaction terms were entered, was statistically significant. However, none of the beta coefficients for the four interaction terms were statistically significant, which indicated the absence of moderation effects of gender or social support in the association of ethnic minority status stress with anxiety symptoms.

4. Discussion

The first two aims of the study were to examine the unique contribution of ethnic minority status stress and social support to depression and anxiety symptoms, and whether gender moderated the association of ethnic minority status stress and social support to depression and anxiety symptoms. Consistent with expectations, the findings indicated that ethnic minority status stress contributed unique variance to depression symptoms when accounting for gender, general college stress, and social class. Similar findings were reported in a few earlier studies with groups of Hispanic [10,15] and diverse ethnic minority college students [13]. While no previous studies were located regarding anxiety symptoms, the results also indicated that ethnic minority status stress was positively associated with anxiety symptoms when controlling for gender and general college stress. However, once social support was entered into the regression model, ethnic minority status stress continued to contribute unique variance to depression symptoms but not to anxiety symptoms.

The results of this study also indicated that gender did not moderate the positive association of ethnic minority status stress with depression or anxiety symptoms. These findings support the proposition that, in addition to college stress, Hispanic college women and men are likely to experience minority status-related stress, which may exacerbate the negative effect of general college stress on students’ psychological distress. However, these effects may be stronger in relation to depression than anxiety symptoms.

The third aim of the study was to examine whether social support moderated the association of ethnic minority status stress with depression and anxiety symptoms, and whether the moderation effect differed for college women and men. The results regarding the two- and three-way interaction effects indicated that the negative association of social support with depression symptoms was stronger for women than men. Similarly, the social support moderation effect in relation to depression symptoms was present only for women. That is, ethnic minority status stress was positively associated with depression symptoms only among Hispanic college women who reported lower levels of social support, while among men, ethnic minority status stress was positively associated with depression symptoms regardless of social support level. Taken together, these findings suggest that in the presence of ethnic minority status stress, social support may play a stronger protective role for depression symptoms among Hispanic college women than men. Future studies are needed to identify and examine factors that may buffer the association of ethnic minority status stress with depression symptoms among Hispanic college men.

The protective role of social support in relation to depressive symptoms among women is consistent with familism, a salient value in Hispanic culture that emphasizes closeness, interdependence, and mutual help within the nuclear and extended family [44]. Hispanic women typically report higher levels of familism and adherence to traditional family values than Hispanic men [45], which suggests that in times of stress, they may be more likely than their male counterparts to reach out to family and friends and benefit from the support they receive.

Inconsistent with the findings from a few earlier studies [28,29], social support did not buffer the association of ethnic minority status stress with anxiety symptoms. The cognitive–behavioral perspective regarding the differences between depression and anxiety mental schemas may help explain this finding. Depressive cognition usually reflects a negative view of the self, a sense of failure, and reduced motivation to engage in activities, which further contribute to a negative view of self [46,47]. Similarly, ethnic minority status stress and related discrimination and exclusionary experiences are likely to lead to lower self-esteem and feelings of isolation [48]. Social support, which has been associated with lower feelings of loneliness among college students [49], may be particularly protective against depression symptoms compared to anxiety symptoms that are characterized by a sense of threat and fear [50]. Further research is needed to examine moderators of the association of ethnic minority status stress to anxiety symptoms among Hispanic college women and men.

Consistent with previous studies [21,22,23,24], the findings suggested that the positive impact of social support in ameliorating depressive symptoms was present only for women. These findings imply that difficulties in interpersonal relations and lack of social support may be salient in the development of depression symptoms among women, particularly when facing stressors that challenge their sense of self-esteem or engender feelings of isolation [46,47,48]. Earlier studies have also reported that women are more likely than men to form close emotional relationships with others in which they seek and provide social support [22,26,27,28,46]. It is possible that responding to the support needs of close others may be an additional source of strain for women [23,51]. Therefore, it seems important to consider in clinical interventions with women issues of balance and reciprocity within their social networks so that women can benefit from the social support available to them without experiencing undue levels of additional strain [23].

5. Limitations and Future Research

There were some limitations in this study that must be noted when interpreting its results. The findings may not generalize to Hispanic students attending universities in other geographical regions of the U.S. or that are not considered Hispanic-serving institutions. Only self-report measures were used to assess the constructs of interest, which may be subject to respondents’ bias. Survey items were presented to all participants in the same order. Therefore, it is possible that students experienced fatigue towards the end of survey completion, which may have impacted their responses. The study’s correlational design does not allow for inferences of cause and effect regarding the relation of general college stress, ethnic minority status stress, and social support with depression or anxiety symptoms. Other limitations included the lack of information regarding the family history of anxiety and depression symptoms and how this family history affects Hispanic college students’ strategies to deal with depression and anxiety. Finally, participants included students with different national and cultural backgrounds (e.g., Mexico, El Salvador, Puerto Rico, and countries in Central and South America) and migration status (e.g., undocumented, permanent residents, and American citizens), which may hide important sociocultural differences in minority status stress experience, coping strategies, and perceptions of availability of social support.

Researchers may want to replicate this study with more ethnically diverse samples to examine to what extent the findings generalize to women and men from other ethnic minority groups in the U.S. and those not attending college. Similarly, further research could examine to what extent social support moderates the association of stressors to other outcomes, including well-being, resilience, and markers of academic success (e.g., college retention and grades). The results of future qualitative studies may be helpful to further understand what aspects of social support Hispanic women perceive as most important in helping them cope with different types of stressors. Similarly, future studies could examine quantitative mediation models to identify the mechanisms through which social support buffers the association of stress with mental health, including stress appraisal, increased self-efficacy, and the promotion of adaptive coping behaviors.

6. Conclusions

In sum, the findings indicated that in addition to general college stress, Hispanic college women and men may be exposed to unique stressors associated with their ethnic group membership, which may increase their risk of experiencing psychological distress. Therefore, counseling services and outreach efforts in college campuses should consider potential ethnic minority status stressors that may impact the psychological well-being and academic success of Hispanic students. The results also indicated that while social support was negatively related to depression and anxiety symptoms for both men and women, social support buffered the association of ethnic minority stress with depression symptoms only for women. That is, ethnic minority status stress was not associated with depression symptoms among women with higher levels of social support. These findings suggest that social support is particularly important in helping college women cope with ethnic related stressors and reducing the impact of such stressors on their distress symptoms. Therefore, colleges and universities may want to assess levels of social support quality among the general student population and those seeking mental health services to assess the risk of mental health issues [52], particularly among women. Furthermore, the study’s findings highlight the importance of considering gender differences when examining the role of social support in mental health, particularly in addressing depression symptoms related to ethnic minority status stress.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M., R.H.M., N.O. and C.A.; methodology, L.M., W.F. and C.A.; analysis, L.M., W.F. and C.A.; writing—original draft preparation L.M., C.A. and R.H.M.; writing—review and editing, L.M., R.H.M., N.O., W.F. and C.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no funding to conduct this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the university’s institutional review board (IRB) under Protocol Number 16580.

Informed Consent Statement

Students consented to participating in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data may be available upon request due to privacy considerations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United States Census Bureau. New Estimates Highlight Differences in Growth Between the U.S. Hispanic and Non-Hispanic Populations (Press Release Number: CB24-109). 2024. Available online: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2024/population-estimates-characteristics.html (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Mora, L. Hispanic Enrollment Reaches New High at Four-Year Colleges in the U.S., But Affordability Remains an Obstacle. 2022. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/10/07/hispanic-enrollment-reaches-new-high-at-four-year-colleges-in-the-u-s-but-affordability-remains-an-obstacle/ (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Center for Collegiate Mental Health. Annual Report 2020. 2019. Available online: https://ccmh.psu.edu/assets/docs/2020%20CCMH%20Annual%20Report.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- American College Health Association. American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment III: Reference Group Executive Summary. 2024. Available online: https://www.acha.org/wp-content/uploads/NCHA-IIIb_SPRING_2024_REFERENCE_GROUP_EXECUTIVE_SUMMARY.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- BlackDeer, A.A.; Wolf, D.A.P.; Maguin, E.; Beeler-Stinn, S. Depression and anxiety among college students: Understanding the impact on grade average and differences in gender and ethnicity. J. Am. Coll. Health 2023, 71, 1091–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, J.B.; Eisenberg, D.; Lu, L.; Gathright, M. Racial/ethnic disparities in mental health care utilization among U.S. college students: Applying the Institution of Medicine Definition of health care disparities. Acad. Psychiatry 2015, 39, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, D.; Golberstein, E.; Hunt, J.B. Mental health and academic success in college. BE J. Econ. Anal. Policy 2009, 9, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargrove, T.W.; Halpern, C.T.; Gaydosh, L.; Hussey, J.M.; Whitsel, E.A.; Dole, N.; Hummer, R.A.; Harris, K.M. Race/ethnicity, gender, and trajectories of depressive symptoms across early- and mid-life among the Add Health Cohort. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2020, 7, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hysenbegasi, A.; Hass, S.L.; Rowland, C.R. The impact of depression on the academic productivity of university students. J. Ment. Health Policy Econ. 2005, 8, 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Arbona, C.; Fan, W.; Olvera, N. College stress, minority status stress, depression, grades, and persistence intentions among Hispanic female students: A mediation model. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2018, 40, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbona, C.; Jimenez, C. Minority stress, ethnic identity, and depression among Latino/a college students. J. Couns. Psychol. 2014, 61, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedley, B.D.; Myers, H.F.; Harrell, S.P. Minority-status stresses and the college adjustment of ethnic minority freshmen. J. High. Educ. 1993, 64, 434–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Liao, K.Y.H.; Chao, R.C.L.; Mallinckrodt, B.; Tsai, P.C.; Botello-Zamarron, R. Minority stress perceived bicultural competence, and depressive symptoms among ethnic minority college students. J. Couns. Psychol. 2010, 57, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Ku, T.Y.; Liao, K.Y. Minority stress and college persistence attitudes among African American, Asian American, and Latino students: Perception of university environment as a mediator. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2011, 17, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaiña, D.H. Acculturative stress: Minority status and distress. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 1994, 16, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piña-Watson, B.; Dornhecker, M.; Salinas, S.R. The impact of bicultural stress on Mexican American adolescents’ depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation: Gender matters. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2015, 37, 342–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiders, K.H.; Umaña-Taylor, A.J.; Derlan, C.L. Trajectories of depressive symptoms and self-esteem in Latino youths: Examining the role of gender and perceived discrimination. Dev. Psychol. 2013, 49, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarevic, V.; Crovetto, F.; Shapiro, A.F. Challenges of Latino young men and women: Examining the role of gender in discrimination and mental health. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 94, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S. Social relationships and health. Am. Psychol. 2004, 59, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zell, E.; Stockus, C.A. Social support and psychological adjustment: A quantitative synthesis of 60 meta-analyses. Am. Psychol. 2025, 80, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalgard, O.S.; Dowrick, C.; Lehtinen, V.; Vazquez-Barquero, J.L.; Casey, P.; Wilkinson, G.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Page, H.; Dunn, G.; ODIN Group. Negative life events, social support and gender difference in depression. Soc. Psychiatry Epidemiol. 2006, 41, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendler, K.S.; Myers, J.; Prescott, C.A. Sex differences in the relationship between social support and risk for major depression: A longitudinal study of opposite-sex twin pairs. Am. J. Psychiatry 2005, 162, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneavel, M. Relationship between gender, stress, and quality of social support. Psychol. Rep. 2021, 124, 1481–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, R.; Espetvedt, M.N.; Lyshol, H.; Clench-Aas, J.; Myklestad, I. Mental distress among young adults-gender differences in the role of social support. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueger, S.Y.; Malecki, C.K.; Pyun, Y.; Aycock, C.; Coyle, S. A meta-analytic review of the association between perceived social support and depression in childhood and adolescence. Psychol. Bull. 2016, 142, 1017–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedrov, A.; Gable, S.L. Thriving together: The benefits of women’s social ties for physical, psychological and relationship health. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2023, 378, 20210441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, A.L.; Livingstone, H.A. Gender differences in perceptions of stressors and utilization of social support among university students. Can. J. Behav. Sci./Rev. Can. Sci. Comport. 2003, 35, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asberg, K.K.; Bowers, C.; Renk, K.; McKinney, C. A structural equation modeling approach to the study of stress and psychological adjustment in emerging adults. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2008, 39, 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinajero, C.; Martínez-López, Z.; Rodríguez, M.S.; Guisande, M.A.; Páramo, M.F. Gender and socioeconomic status differences in university students’ perception of social support. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2015, 30, 227–244. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/43551181 (accessed on 30 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Corona, R.; Rodríguez, V.M.; McDonald, S.E.; Velazquez, E.; Rodríguez, A.; Fuentes, V.E. Associations between cultural stressors, cultural values, and Latina/o college students’ mental health. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 46, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Esparza, Y.; Espinosa, P.R.; Verney, S.P.; Boursaw, B.; Smith, B.W. Social Support protects against symptoms of anxiety and depression: Key variations in Latinx and Non-Latinx White college students. J. Latinx Psychol. 2021, 9, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffaelli, M.; Andrade, F.C.D.; Wiley, A.R.; Sanchez-Armass, O.; Edwards, L.L.; Aradillas-Garcia, C. Stress, social support, and depression: A test of the stress-buffering hypothesis in a Mexican sample. J. Res. Adolesc. 2013, 23, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, A.; Piña-Watson, B.; Manzo, G. Resilience through family: Family support as an academic and psychological protective resource for Mexican descent first-generation college students. J. Hisp. High. Educ. 2022, 21, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cariello, A.N.; Perrin, P.B.; Williams, C.D.; Espinoza, G.A.; Paredes, A.M.; Moreno, O.A. Moderating influence of social support on the relation between discrimination and health via depression in Latinx Immigrants. J. Latinx Psychol. 2022, 10, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Waters, S.F. Asians and Asian Americans’ experiences of racial discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic: Impacts on health outcomes and the buffering role of social support. Stigma Health 2021, 6, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Yan, X.; Zhao, F.; Yuan, F. The relationship between perceived stress and adolescent depression: The roles of social support and gender. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 123, 501–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, N.; Myers, H.F.; Morris, J.K.; Cardoza, D. Latino college student adjustment: Does an increased presence offset minority-status and acculturative stresses? J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 30, 1523–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, G.D.; Walker, R.R. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Spport: A confirmatory study. J. Clin. Psychol. 1991, 47, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, S.D.; Fox, R.S.; Malcarne, V.L.; Roesch, S.C.; Champagne, B.R.; Sadler, G.R. The psychometric properties of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 Scale in Hispanic Americans with English or Spanish language preference. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2014, 20, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Educational: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, A.F.; Albers, C.J. Regression assumptions in clinical psychology research practice-a systematic review of common misconceptions. Peer J. 2017, 5, e3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J.F.; Richter, A.W. Probing three-way interactions in moderated multiple regression: Development and application of a slope difference test. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M.M.; Bámaca-Colbert, M.Y. A behavioral process model of familism. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2016, 8, 463–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, B.; Ullman, J.B.; Aguilera, A.; Dunkel Schetter, C. Familism and psychological health: The intervening role of closeness and social support. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2014, 20, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenck, M.W.; Fajkowska, M. Anxiety and depression: Toward overlapping and distinctive features. Cogn. Emot. 2018, 32, 1391–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGinn, L.K. Cognitive behavioral therapy of depression: Theory, treatment, and empirical status. Am. J. Psychother. 2000, 54, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cokley, K.; McClain, S.; Enciso, A.; Martinez, M. An examination of the impact of minority status stress and impostor feelings on the mental health of diverse ethnic minority college students. J. Multicult. Couns. Dev. 2013, 41, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicpon, M.F.; Huser, L.; Blanks, E.H.; Sollenberger, S.; Befort, C.; Kurpius, S.E.R. The relationship of loneliness and social support with college freshmen’s academic performance and persistence. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. Res. Theory Pract. 2006, 8, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, S.G. Cognitive processes during fear acquisition and extinction in animals and humans: Implications for exposure therapy of anxiety disorders. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 28, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crockett, L.J.; Iturbide, M.I.; Torres Stone, R.A.; McGinley, M.; Raffaelli, M.; Carlo, G. Acculturative stress, social support, and coping: Relations to psychological adjustment among Mexican American college students. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2007, 13, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefner, J.; Eisenberg, D. Social support and mental health among college students. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2009, 79, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).