Female Genital Mutilation in Sierra Leone: A Systematic Review of Cultural Practices, Health Impacts, and Pathways to Eradication

Abstract

1. Introduction

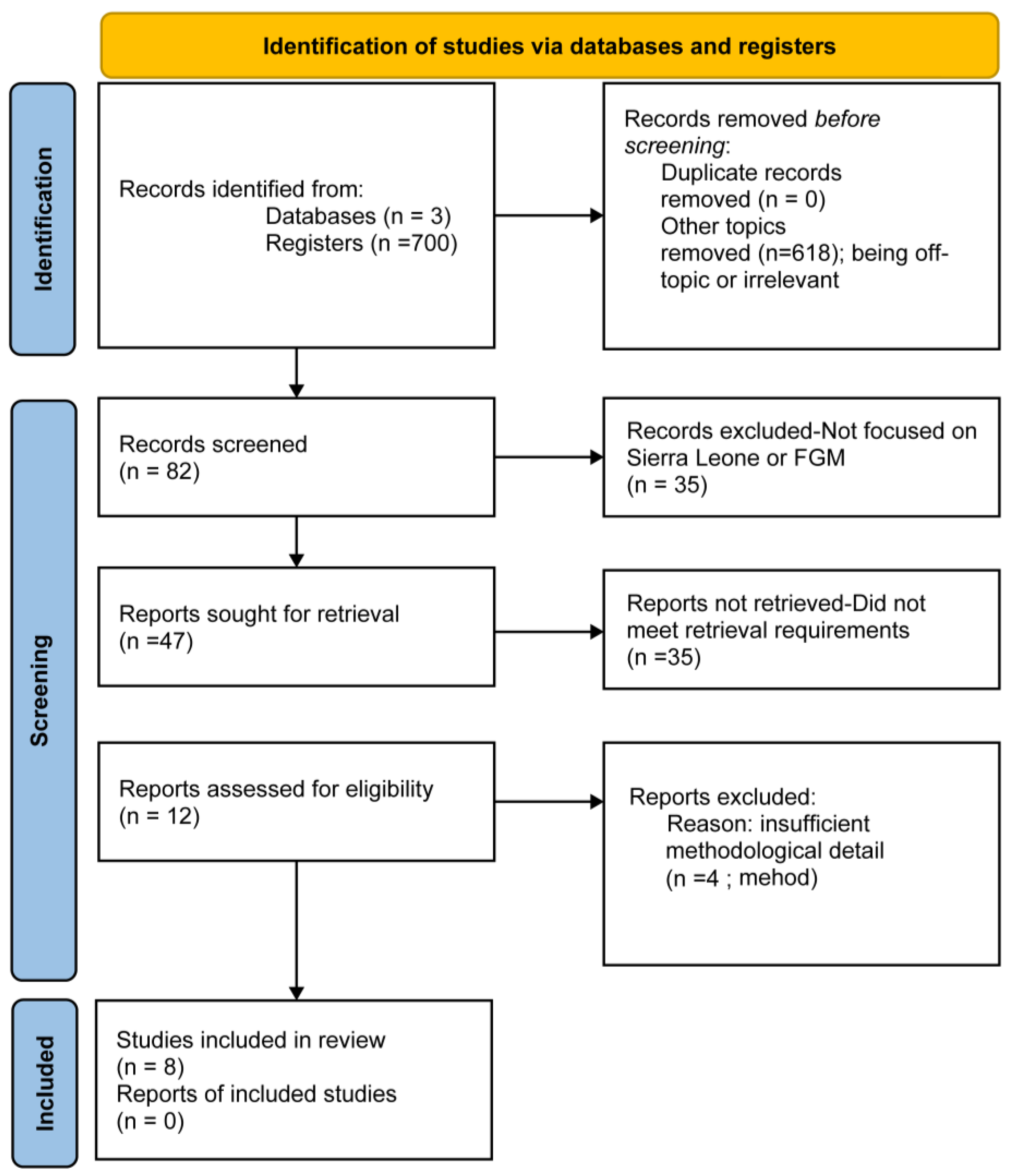

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis Procedure

2.5. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence and Demographic Patterns

3.2. Sociocultural Norms and Intersectionality

3.3. Health Consequences and Healthcare-Seeking Behaviors

3.4. Decision-Making, Medicalization, and Gender Dynamics

3.5. Association Between FGM and Intimate Partner Violence

3.6. Additional Insights

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- UNICEF Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) Statistics [Internet]. 2022. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-protection/female-genital-mutilation/ (accessed on 21 July 2022).

- Obiora, O.L.; Maree, J.E.; Nkosi-Mafutha, N.G. Experiences of young women who underwent female genital mutilation/cutting. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 4104–4115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjälkander, O.; Grant, D.S.; Berggren, V.; Bathija, H.; Almroth, L. Female genital mutilation in sierra leone: Forms, reliability of reported status, and accuracy of related demographic and health survey questions. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2013, 2013, 680926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjälkander, O.; Leigh, B.; Harman, G.; Bergström, S.; Almroth, L. Female genital mutilation in Sierra Leone: Who are the decision makers? Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2012, 16, 119–131. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23444549 (accessed on 1 December 2012).

- Bitong, L. Fighting genital mutilation in Sierra Leone. Bull. World Health Organ. 2005, 83, 806–807. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/269514 (accessed on 1 November 2005).

- Akinsulure-Smith, A.M. Exploring female genital cutting among west African immigrants. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2014, 16, 559–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallon, I.; Dundes, L. The cultural context of the Sierra Leonean Mende woman as patient. J. Transcult. Nurs. Off. J. Transcult. Nurs. Soc. 2010, 21, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.F. The Bondo Society as a Political Tool: Examining Cultural Expertise in Sierra Leone from 1961 to 2018. Laws 2019, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obara Bosire, T. Politics of Female Genital Cutting (FGC), Human Rights, and the Sierra Leone State; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Doumbia, S. Sierra Leone: The Law and FGM; Thomson-Reuters Foundation: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mchenga, M. Female Genital Mutilation and Sexual Risk Behaviors of Adolescent Girls and Young Women Aged 15–24 Years: Evidence From Sierra Leone. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2024, 74, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameyaw, E.K.; Yaya, S.; Seidu, A.A.; Ahinkorah, B.O.; Baatiema, L.; Njue, C. Do educated women in Sierra Leone support discontinuation of female genital mutilation/cutting? Evidence from the 2013 Demographic and Health Survey. Reprod. Health 2020, 17, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameyaw, E.K.; Anjorin, S.; Ahinkorah, B.O.; Seidu, A.A.; Uthman, O.A.; Keetile, M.; Yaya, S. Women’s empowerment and female genital mutilation intention for daughters in Sierra Leone: A multilevel analysis. BMC Women’s Health 2021, 21, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Small, E.; Sharma, B.B.; Nikolova, S.P.; Tonui, B.C. Hegemonic Masculinity Attitudes Toward Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting Among a Sample of College Students in Northern and Southern Sierra Leone. J. Transcult. Nurs. Off. J. Transcult. Nurs. Soc. 2020, 31, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, H.; Swan, L.E.T.; Heaton, L. Polyvictimization and mental health consequences of female genital mutilation/circumcision (FGM/C) among Somali refugees in Kenya. Women Health 2020, 60, 636–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality If Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analyses. 2000. Available online: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Carlijn, V.B.; Brittany, H. Female Genital Mutilation and Age at Marriage: Risk Factors of Physical Abuse for Women in Sierra Leone. J. Fam. Violence 2023, 40, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussaoui, L.S.; Law, E.; Claxton, N.; Itämäki, S.; Siogope, A.; Virtanen, H.; Desrichard, O. Consortium Sierra Leone Red Cross Society Sexual and Reproductive Health: How Can Situational Judgment Tests Help Assess the Norm and Identify Target Groups? A Field Study in Sierra Leone. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 866551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjälkander, O.; Bangura, L.; Leigh, B.; Berggren, V.; Bergström, S.; Almroth, L. Health complications of female genital mutilation in Sierra Leone. Int. J. Women’s Health 2012, 4, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alradie-Mohamed, A.; Kabir, R.; Arafat, S.M.Y. Decision-Making Process in Female Genital Mutilation: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayenew, A.A.; Mol, B.W.; Bradford, B.; Abeje, G. Prevalence of female genital mutilation and associated factors among daughters aged 0–14 years in sub-Saharan Africa: A multilevel analysis of recent demographic health surveys. Front. Reprod. Health 2023, 5, 1105666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, S. Feminist Theory, Agency, and the Liberatory Subject: Some Reflections on the Islamic Revival in Egypt. Temenos-Nord. J. Study Relig. 2006, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanf. Law Rev. 1991, 43, 1241–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, S. Calculating age-specific prevalence rates of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) for use as an input variable in extrapolation calculations and as predictors of future prevalence in countries of origin. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0317845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köbach, A.; Ruf-Leuschner, M.; Elbert, T. Psychopathological sequelae of female genital mutilation and their neuroendocrinological associations. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knipscheer, J.; Vloeberghs, E.; van der Kwaak, A.; van den Muijsenbergh, M. Mental health problems associated with female genital mutilation. BJPsych Bull. 2015, 39, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omigbodun, O.; Bella-Awusah, T.; Groleau, D.; Abdulmalik, J.; Emma-Echiegu, N.; Adedokun, B.; Omigbodun, A. Perceptions of the psychological experiences surrounding female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) among the Izzi in Southeast Nigeria. Transcult. Psychiatry 2020, 57, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diop, N.J.; Askew, I. The effectiveness of a community-based education program on abandoning female genital mutilation/cutting in Senegal. Stud. Fam. Plan. 2009, 40, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esu, E.; Okoye, I.; Arikpo, I.; Ejemot-Nwadiaro, R.; Meremikwu, M.M. Providing information to improve body image and care-seeking behavior of women and girls living with female genital mutilation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. Off. Organ Int. Fed. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2017, 136 (Suppl. S1), 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisel, D.; Creighton, S.M. Long term health consequences of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM). Maturitas 2015, 80, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zsabokorszky, Z.; Van de Velde, S.; Michielsen, K.; Van Eekert, N. Corrigendum: Exploring the association between perceived male attitudes and female attitudes toward the discontinuation of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting in Egypt. Front. Sociol. 2024, 8, 1353912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipsma, H.L.; Chen, P.G.; Ofori-Atta, A.; Ilozumba, U.O.; Karfo, K.; Bradley, E.H. Female genital cutting: Current practices and beliefs in western Africa. Bull. World Health Organ. 2012, 90, 120–127F. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammary, E.; Manasi, K. Mental and sexual health outcomes associated with FGM/C in Africa: A systematic narrative synthesis. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 56, 101813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matanda, D.J.; Eekert, N.V.; Croce-Galis, M.; Gay, J.; Middelburg, M.J.; Hardee, K. Correction: What interventions are effective to prevent or respond to female genital mutilation? A review of existing evidence from 2008–2020. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0004141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekundayo, R.; Robinson, S. An Evaluation of Community-Based Interventions Used on the Prevention of Female Genital Mutilation inWest African Countries. Eur. Sci. J. ESJ 2019, 15, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hombrados, M.I. La Potenciación Comunitaria (Empowerment). Estrategias de la Intervención Psicosocial: Casos Prácticos; Editorial Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2007; ISBN 978-84-368-2144-4. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, S. Transforming Vulnerability into Power: Exploring Empowerment among Women with Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C) in the Context of Migration in Belgium. J. Hum. Dev. Capab. 2011, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doucet, M.H.; Delamou, A.; Manet, H.; Groleau, D. Beyond will: The empowerment conditions needed to abandon female genital mutilation in Conakry (Guinea), a focused ethnography. Reprod. Health 2020, 17, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, J.J.; Brady, S.S.; Chaisson, N.; Mohamed, F.S.; Robinson, B.B.E. Understanding Women’s Responses to Sexual Pain After Female Genital Cutting: An Integrative Psychological Pain Response Model. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2021, 50, 1859–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inman, A.G.; DeBoer Kreider, E. Multicultural competence: Psychotherapy practice and supervision. Psychotherapy 2013, 50, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Aims | Methods | Results | Total Score (1–6) | Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [19] | Explore how FGM and early marriage influence IPV risk. | Logistic regression on DHS 2019 data (n = 3324) | FGM at ages 10–14 is associated with higher IPV risk, the strongest risk among women circumcised under age 10 and married early. | 6 | High |

| [12] | Assess the association between FGM and sexual behaviors in AGYW | Cross-sectional DHS data, generalized estimation equation. | FGM was associated with early sexual debut, adolescent motherhood, and child marriage; education was protective. | 6 | High |

| [20] | Explore norms and beliefs on FGM using innovative measurement | Situational judgment tests (SJTs) with 566 respondents. | FGM norms are stronger than other harmful practices; age-related differences in acceptance are identified. | 4 | Medium |

| [14] | Investigate the link between women’s empowerment and intention to cut daughters. | Multilevel logistic regression on DHS 2013 data (n = 7706). | Low empowerment is linked to a higher intention to cut knowledge and agency associated with opposition to FGM. | 6 | High |

| [13] | Examine educational attainment and attitudes toward FGM discontinuation. | Logistic regression on DHS 2013 data (n = 15,228). | Higher education, Christianity, urban residence, and wealth correlated with support for FGM abandonment. | 6 | High |

| [4] | Investigate FGM health complications and care-seeking behaviors. | Structured interviews with 258 women attending clinics. | 84.5% reported complications; most sought traditional rather than professional healthcare. | 4 | Medium |

| [5] | Identify decision-makers for FGM and assess medicalization. | Structured interviews with 310 girls aged 10–20. | Women are primary decision-makers; fathers are involved in 28% and 13% of FGM procedures performed by health professionals. | 3 | Medium |

| [21] | Assess forms of FGM and validate self-reported status. | Cross-sectional clinical study (n = 558). | High agreement between self-reported and clinically observed FGM status; discrepancies in classification details. | 5 | High |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodríguez-Pastor, J.A.; Molina-Fernández, A.J. Female Genital Mutilation in Sierra Leone: A Systematic Review of Cultural Practices, Health Impacts, and Pathways to Eradication. Women 2025, 5, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5020018

Rodríguez-Pastor JA, Molina-Fernández AJ. Female Genital Mutilation in Sierra Leone: A Systematic Review of Cultural Practices, Health Impacts, and Pathways to Eradication. Women. 2025; 5(2):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5020018

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez-Pastor, Julia Argentina, and Antonio Jesús Molina-Fernández. 2025. "Female Genital Mutilation in Sierra Leone: A Systematic Review of Cultural Practices, Health Impacts, and Pathways to Eradication" Women 5, no. 2: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5020018

APA StyleRodríguez-Pastor, J. A., & Molina-Fernández, A. J. (2025). Female Genital Mutilation in Sierra Leone: A Systematic Review of Cultural Practices, Health Impacts, and Pathways to Eradication. Women, 5(2), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5020018