Black Mothers’ Experiences of Having a Preterm Infant: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Objective and Research Question

2. Results

2.1. Characteristics of the Studies

2.2. Lack of Parental Engagement in NICU

2.3. Racism in the NICU

2.4. Stress of Transitioning Home

2.5. Availability of Support Systems

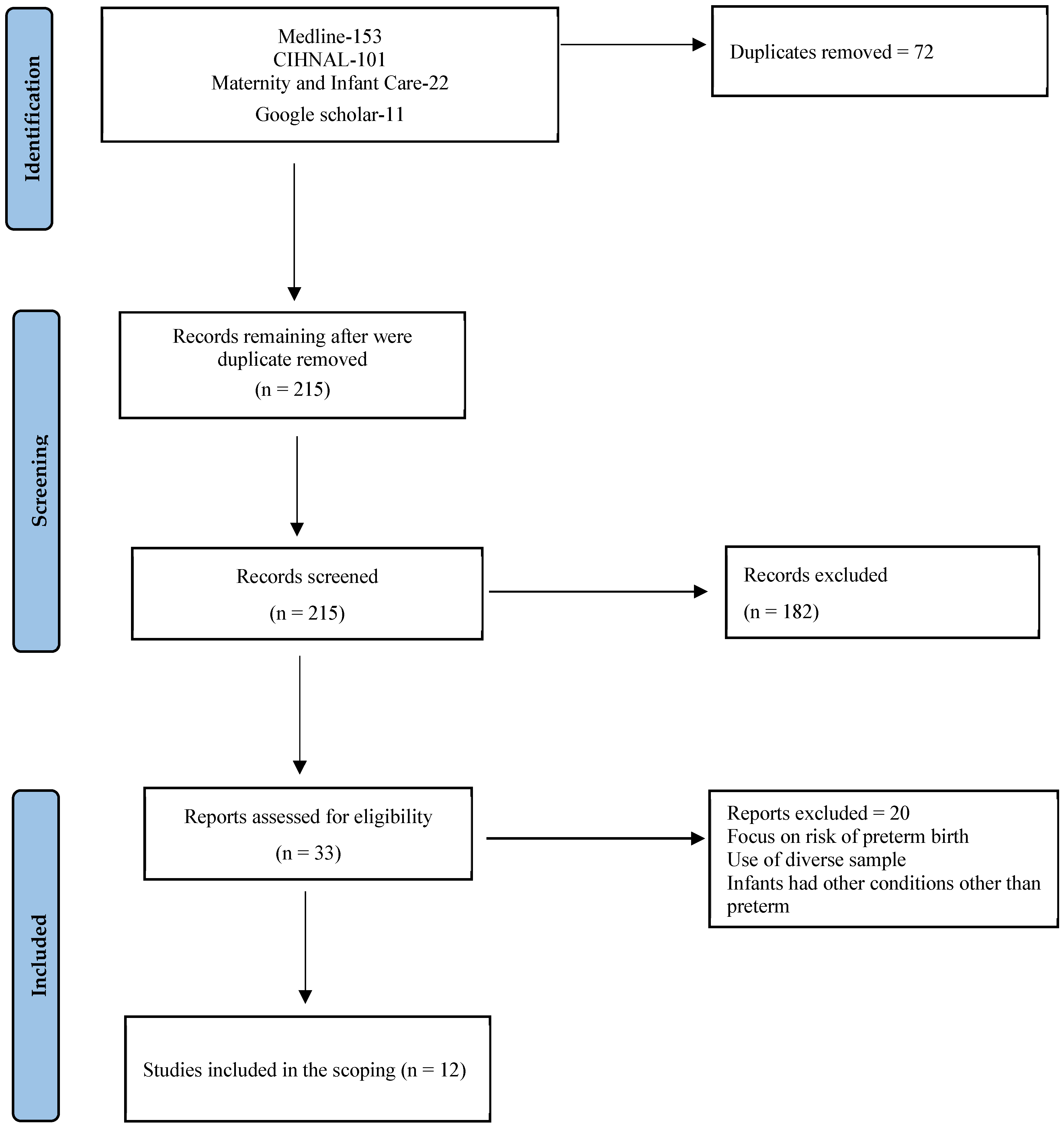

3. Methods and Materials

3.1. Research Question

3.2. Searching for Relevant Studies

3.3. Selection of Studies

3.4. Data Extraction

3.5. Collating, Summarizing and Reporting the Result

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walani, S.R. Global burden of preterm birth. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 150, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Born too Soon: Decade of Action on Preterm Birth; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/ (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Galson, S.K. Preterm Birth as a Public Health Initiative. Public Health Rep. 2008, 123, 548–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormick, M.C.; Litt, J.S.; Smith, V.C.; Zupancic, J.A. Prematurity: An Overview and Public Health Implications. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2011, 32, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braveman, P.; Dominguez, T.P.; Burke, W.; Dolan, S.M.; Stevenson, D.K.; Jackson, F.M.; Collins, J.W.; Driscoll, D.A.; Haley, T.; Acker, J.; et al. Explaining the Black-White Disparity in Preterm Birth: A Consensus Statement from a Multi-Disciplinary Scientific Work Group Convened by the March of Dimes. Front. Reprod. Health 2021, 3, 684207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSisto, C.L.; Hirai, A.H.; Collins, J.W., Jr.; Rankin, K.M. Deconstructing a Disparity: Explaining Excess Preterm Birth among U.S.-Born Black Women. Ann. Epidemiol. 2018, 28, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoma, M.E.; Drew, L.B.; Hirai, A.H.; Kim, T.Y.; Fenelon, A.; Shenassa, E.D. Black–White Disparities in Preterm Birth: Geographic, Social, and Health Determinants. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 57, 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLemore, M.R.; Berkowitz, R.L.; Oltman, S.P.; Baer, R.J.; Franck, L.; Fuchs, J.; Karasek, D.A.; Kuppermann, M.; McKenzie-Sampson, S.; Melbourne, D.; et al. Risk and Protective Factors for Preterm Birth among Black Women in Oakland, California. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2021, 8, 1273–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionio, C.; Mascheroni, E.; Colombo, C.; Castoldi, F.; Lista, G. Stress and feelings in mothers and fathers in NICU: Identifying risk factors for early interventions. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2019, 20, e81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendy, A.; El-Sayed, S.; Bakry, S.; Mohammed, S.M.; Mohamed, H.; Abdelkawy, A.; Hassani, R.; Abouelela, M.A.; Sayed, S. The Stress Levels of Premature Infants’ Parents and Related Factors in NICU. SAGE Open Nurs. 2024, 10, 23779608241231172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malliarou, M.; Karadonta, A.; Mitroulas, S.; Paralikas, T.; Kotrotsiou, S.; Athanasios, N.; Sarafis, P. Preterm Parents’ Stress and Coping Strategies in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit in a University Hospital of Central Greece. Mater. Socio-Medica 2021, 33, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittingham, K.; Boyd, R.N.; Sanders, M.R.; Colditz, P. Parenting and Prematurity: Understanding Parent Experience and Preferences for Support. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2014, 23, 1050–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, K.; Rowe, J.; Barnes, M.; Kearney, L. The Parenting Premmies Support Program: Designing and developing a mobile health intervention for mothers of preterm infants. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2021, 7, 1865617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.O.C.; Kronborg, H.; Aagaard, H.; Brinchmann, B.S. The journey towards motherhood after a very preterm birth: Mothers’ experiences in hospital and after home-coming. J. Neonatal Nurs. 2013, 19, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeidat, H.M.; Bond, E.A.; Callister, L.C. The Parental Experience of Having an Infant in the Newborn Intensive Care Unit. J. Perinat. Educ. 2009, 18, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbar, J.D.; Edwards, E.M.; Greenberg, L.T.; Profit, J.; Draper, D.; Helkey, D.; Lorch, S.A.; Lee, H.C.; Phibbs, C.S.; Rogowski, J.; et al. Racial Segregation and Inequality in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit for Very Low-Birth-Weight and Very Preterm Infants. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurdson, K.; Morton, C.; Mitchell, B.; Profit, J. Disparities in Nicu Quality of Care: A Qualitative Study of Family and Clinician Accounts. J. Perinatol. 2018, 38, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padula, A.M.; Shariff-Marco, S.; Yang, J.; Jain, J.; Liu, J.; Conroy, S.M.; Carmichael, S.L.; Gomez, S.L.; Phibbs, C.; Oehlert, J.; et al. Multilevel Social Factors and Nicu Quality of Care in California. J. Perinatol. 2020, 41, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gralton, K.S.; Doering, J.; Ngui, E.; Pan, A.; Schiffman, R. Family Resiliency and Family Functioning in Non-Hispanic Black and Non-Hispanic White Families of Preterm Infants. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2022, 64, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.E.; D’Agostino, J.A.; Passarella, M.; Lorch, S.A. Racial Differences in Parental Satisfaction with Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Nursing Care. J. Perinatol. 2016, 36, 1001–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuetz Haemmerli, N.; Stoffel, L.; Schmitt, K.-U.; Khan, J.; Humpl, T.; Nelle, M.; Cignacco, E. Enhancing Parents’ Well-Being after Preterm Birth—A Qualitative Evaluation of the “Transition to Home” Model of Care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estriplet, T.; Morgan, I.; Davis, K.; Crear Perry, J.; Matthews, K. Black Perinatal Mental Health: Prioritizing Maternal Mental Health to Optimize Infant Health and Wellness. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 807235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, K.; Morgan, I.; Davis, K.; Estriplet, T.; Perez, S.; Crear-Perry, J.A. Pathways to Equitable and Antiracist Maternal Mental Health Care: Insights from Black Women Stakeholders. Health Aff. 2021, 40, 1597–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, A. Reframing the Narrative: Black Maternal Mental Health and Culturally Meaningful Support for Wellness. Infant Ment. Health J. 2021, 42, 502–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajayi, K.V.; Garney, W.R. Understanding the Domains of Experiences of Black Mothers with Preterm Infants in the United States: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2023, 10, 2453–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witt, R.E.; Malcolm, M.; Colvin, B.N.; Gill, M.R.; Ofori, J.; Roy, S.; Lenze, S.N.; Rogers, C.E.; Colson, E.R. Racism and Quality of Neonatal Intensive Care: Voices of Black Mothers. Pediatrics 2022, 150, e2022056971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Discenza, D. Racism in the NICU: It Exists and It Needs to Stop. Neonatal Netw. 2021, 40, 340–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magruder, L. African American Mothers’ Experience in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Ph.D. Thesis, Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2021. Available online: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations/10307 (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Waldron, M.K. NICU Parents of Black Preterm Infants: Application of the Kenner Transition Model. Adv. Neonatal Care 2022, 22, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, K.V.; Garney, W.R. What Black Mothers with Preterm Infants Want for Their Mental Health Care: A Qualitative Study. Women’s Health Rep. 2023, 4, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enlow, E.; Faherty, L.J.; Wallace-Keeshen, S.; Martin, A.E.; Shea, J.A.; Lorch, S.A. Perspectives of Low Socioeconomic Status Mothers of Premature Infants. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20162310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, J.B.; Pickler, R.H. Hospital-To-Home Transition of Mothers of Preterm Infants. MCN Am. J. Matern. Child Nurs. 2011, 36, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, K.V.; Page, R.; Montour, T.; Garney, W.R.; Wachira, E.; Adeyemi, L. ‘We are suffering. Nothing is changing.’ Black mother’s experiences, communication, and support in the neonatal intensive care unit in the United States: A Qualitative Study. Ethn. Health 2024, 29, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldron, M.K. Parent Protector: Perceptions of NICU-to-Home Transition Readiness for NICU Parents of Black Preterm Infant. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2022, 36, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LoVerde, B.; Falck, A.; Donohue, P.; Hussey-Gardener, B. Supports and Barriers to the Provision of Human Milk by Mothers of African American Preterm Infants. Adv. Neonatal Care 2018, 18, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brentley, A.L. Importance of Perceived Social Support for Black Mothers of Preterm Babies. Ph.D. Thesis, Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Holditch-Davis, D.; Miles, M.S.; Weaver, M.A.; Black, B.; Beeber, L.; Thoyre, S.; Engelke, S. Patterns of distress in African-American mothers of preterm infants. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2009, 30, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, R.E.; Colvin, B.N.; Lenze, S.N.; Forbes, E.S.; Parker, M.G.; Hwang, S.S.; Rogers, C.E.; Colson, E.R. Lived Experiences of Stress of Black and Hispanic Mothers during Hospitalization of Preterm Infants in Neonatal Intensive Care Units. J. Perinatol. 2021, 42, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, M.; Mardani, A.; Harding, C.; Basirinezhad, M.H.; Vaismoradi, M. Nurses’ strategies to provide emotional and practical support to the mothers of preterm infants in the neonatal intensive care unit: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Women’s Health 2022, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, E.C.; Du, N.; Hawes, K.; Tucker, R.; O’Donnell, M.; Vohr, B. Maternal Mental Health and Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Discharge Readiness in Mothers of Preterm Infants. J Pediatr. 2017, 184, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, A.P.; Halemani, K.; Issac, A.; Thimmappa, L.; Dhiraaj, S.; Radha, K.; Mishra, P.; Upadhyaya, V.D. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and stress among parents of neonates admitted to neonatal intensive care unit: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Exp. Pediatr. 2024, 67, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, L.; Colditz, P.B.; Sanders, M.R.; Boyd, R.N.; Pritchard, M.; Gray, P.H.; Whittingham, K.; Forrest, K.; Leeks, R.; Webb, L.; et al. Depression, posttraumatic stress and relationship distress in parents of very preterm infants. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2018, 21, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Concept 1 | Concept 2 | Concept 3 | Concept 4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black mothers OR Black parents OR Black women OR Black person OR African American mothers OR African American women OR African American Parents OR Black American mothers OR Black American parent OR Women of colour OR African Caribbean Black parent OR African Caribbean Black mothers OR African Caribbean Black women OR Black Canadian women OR Black Canadian mothers OR Black British women OR Black British mothers | AND | Preterm infant OR Preterm baby OR Preterm birth OR Premature infant OR Premature baby OR Premature birth OR Low birthweight baby OR Low birthweight infant OR Very Low birthweight baby OR Very Low birthweight infant | AND | Experiences Views Perspectives Perceptions | AND | Discharge OR Transition OR Transfer OR Readiness OR Preparedness OR Discharge planning OR Neonatal intensive care OR Neonatal intensive care unit OR NICU OR Intensive Care, Neonatal OR Intensive Care Units, Neonatal. |

| Reference and Location | Purpose | Study Design | Sample | Summary of Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discenza, 2021, United States. [26] | To understand the experience of implicit bias and racism in the NICU and how it is not always shown openly with a 3-time preemie mom. | Qualitative Study | 1 Black mother | Families were not provided with valuable information and resources; racism in the NICU was pervasive and manifested in subtle and invisible ways. |

| Griffin & Pickler, 2011, United States [27] | To describe mothers’ experiences during the first month after their preterm infant’s hospital discharge. | Descriptive phenomenology | 10 African American mothers | Financial and family support are integral to a smoother transition to the home; lack of open communication with NICU staff contributed to tension and challenges during hospitalization |

| Magruder, 2021, United States [28] | To explore the lived experience of African American mothers who have had a preterm infant in the NICU. | Qualitative hermeneutic phenomenological design | 8 Black/African American mothers. | Diversity and representation in NICU increased connection and more positive experiences; lack of adequate information on procedures left mothers feeling unprepared. |

| Witt et al., 2022, United States [29] | To understand Black mothers’ perspectives of the impact of racism on quality of care for Black preterm infants in the NICU and what might be done to address it. | Qualitative design | 20 Black mothers | Racism and stereotypes affected the interaction of parents at NICU; lack of Black representation in NICU staffing contributed to racism and absence of culturally informed care. |

| Waldron, 2022a, United States [30] | To explore perceived parental readiness to care for their Black preterm infants at home after discharge from a NICU. | Descriptive qualitative design | 10 Black parents | Implicit or unconscious bias and mistrust interfered with quality and level of communication between NICU staff and parents. |

| Ajayi & Garney, 2023, United States [31] | To examine the existing mental health services and resources in the NICU for Black mothers with preterm infants. | Grounded Theory | 11 Black Mothers | Stress from juggling multiple life demands while in the NICU and after discharge and uncertainties about their infant’s health. |

| Enlow et al., 2016, United Studies [32] | To understand the experiences of at-risk families during the transition from NICU to home to inform interventions. | Grounded theory | 27 mothers of infants born at <35 weeks’ gestation, meeting low socioeconomic status criteria (85% were Black) | Parents felt stressed about the transition from the closely monitored environment of the NICU to the less supervised; inconsistent information from various providers threatened to compromise trust. |

| LoVerde et al., 2018, United States [33] | To explore supports and barriers experienced by African American mothers while providing their own (mother’s) milk to their Very Low Birth Weight infants. | Qualitative descriptive study | 9 African American mothers | Mothers reported being emotionally distressed due to infant’s condition and not expressing enough breastmilk. |

| Ajayi et al., 2023, United States [34] | To understand Black mothers’ perceived provider communication, support needs, and overall experiences in the NICU. | Grounded Theory | 12 Black mothers | Healthcare providers exhibited dismissive attitudes; balancing familial responsibilities and infant needs in NICU and during transition was challenging. |

| Waldron, 2022b, United States [35] | To examine how well the concept of parental readiness to care for Black preterm infants post-NICU discharge aligns with the updated Kenner Transition Model. | Qualitative descriptive research | 10 parents of 8 Black preterm infants | Dismissive encounters and lack of attention and integration of mother perspective in the care of preterm infants; involvement in the NICU care environment and the decision-making process for their preterm infant was vital. |

| Brentley, 2019, United States [36] | To explore Black mothers’ perceptions of social support for their preterm babies. | Phenomenological design | 12 Black mothers | Lack of support and challenges managing medical appointments for child, and limited mobility |

| Holditch-Davis et al., 2009. United States [37] | To examine the various forms of stress experienced by African American mothers of preterm infants, including infant appearance and behavior in the NICU, parental role alteration stress in the NICU, depressive symptoms, state anxiety, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and daily hassles. | Longitudinal Analysis | 177 African American biological mothers of preterm infants | Stress due to infant appearance and behavior in the NICU and parental role alteration. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boakye, P.N.; Prendergast, N.; Thomas Obewu, O.A.; Hayrabedian, V. Black Mothers’ Experiences of Having a Preterm Infant: A Scoping Review. Women 2025, 5, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5010003

Boakye PN, Prendergast N, Thomas Obewu OA, Hayrabedian V. Black Mothers’ Experiences of Having a Preterm Infant: A Scoping Review. Women. 2025; 5(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoakye, Priscilla N., Nadia Prendergast, Ola Abanta Thomas Obewu, and Victoria Hayrabedian. 2025. "Black Mothers’ Experiences of Having a Preterm Infant: A Scoping Review" Women 5, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5010003

APA StyleBoakye, P. N., Prendergast, N., Thomas Obewu, O. A., & Hayrabedian, V. (2025). Black Mothers’ Experiences of Having a Preterm Infant: A Scoping Review. Women, 5(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5010003