Abstract

Intrauterine devices (IUDs) are highly effective long-acting contraceptives. However, pain associated with insertion deters some women and impacts satisfaction. This systematic review critically evaluates the effectiveness of local anesthetics, misoprostol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and conscious sedation for managing pain associated with IUD insertion. A comprehensive database search including PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, ClinicalTrials.gov, and ProQuest was conducted from inception to July 2023 for randomized controlled trials (RCTs). RCTs assessing interventions for IUD insertion pain were included. Case reports, non-randomized studies, and non-English papers were excluded. Two independent reviewers extracted data on pain outcomes and adverse effects. The risk of bias was assessed using Cochrane tools. Thirty-nine RCTs (n = 12,345 women) met the inclusion criteria. Topical lidocaine effectively reduced pain on consistent findings across multiple high-quality RCTs. Misoprostol pretreatment facilitated easier insertions through cervical ripening. However, evidence for NSAIDs was inconclusive, with some RCTs finding no additional benefits versus placebo. Results also remained unclear for nitrous oxide conscious sedation due to variability in protocols. Nulliparity predicted higher reported pain consistently. Lidocaine and misoprostol show promise for minimizing IUD insertion pain and difficulty. Further optimization is required to standardize conscious sedation and fully evaluate NSAIDs. Improving pain management may increase favorable experiences and uptake of this reliable method.

1. Introduction

Intrauterine devices (IUDs) have become one of the most popular and highly efficient long-acting reversible contraceptive methods for women [1]. The exceptional effectiveness of IUDs has been demonstrated to be extremely high, making them cost-effective and suitable for a wide variety of women, leading to an overall high user satisfaction rate [2]. IUDs are available either as a copper-based or as a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (NG-IUS) [3]. The reliability of IUDs is considered high across all types, with copper-based and NG-IUS having an efficacy rate of more than 99% [4]. Beyond their role in preventing unwanted pregnancies, IUDs have other non-contraceptive benefits that include decreased menstrual blood loss, improved dysmenorrhea, improved pelvic pain associated with endometriosis, and protection of the endometrium from hyperplasia [5,6]. However, despite the numerous advantages of IUDs, increased pain and anxiety are still considered significant barriers. Studies have shown that increased anticipated pain is associated with increased perceived pain with IUD insertion [7,8]. Moreover, pain during insertion has been linked to failed insertions, syncope, and vasovagal reactions [9]. A participants-blinded randomized trial conducted in Brazil from 2021 to 2022 to compare different IUD types with varying pain outcomes revealed that a higher Visual Analog Scale (VAS) was associated with levonorgestrel 52 mg IUD [10]. Similarly, a Swedish study on LNG-IUS insertions in nulliparous women revealed that nearly 90% of participants experienced moderate to severe pain during the procedure [11]. A review paper that provided practical advice for avoidance of pain associated with the insertion of intrauterine contraceptives mentioned that for women who experience severe anxiety before obtaining an IUD inserted, after cervical priming, it may be helpful to consider undergoing conscious sedation accompanied by proper monitoring to reduce the anticipated pain [12]. On the contrary, a clinical trial was performed on nulliparous women who received an IUD insertion. The results showed that using 50% nitrous oxide and 50% oxygen (N2O/O2) did not reduce the pain, in contrast to using only oxygen as a placebo [13]. Further research and interventions focusing on pain management during IUD insertions may enhance the overall acceptance and utilization of this highly effective contraceptive method. To date, no definitive evidence supports an effective strategy for minimizing pain during IUD placement. A Cochrane review conducted in 2015 concluded that while some lidocaine formulations, tramadol, and naproxen had some effect on reducing insertion-related pain in specific groups, NSAIDs, lidocaine 2% gel, and misoprostol were ineffective in decreasing pain during IUD insertion [14]. Moreover, a more recent meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials conducted in 2018 concluded that lidocaine was associated with reduced pain levels during and after IUD replacement [15]. Furthermore, a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs in 2018, which evaluated different pain-lowering medications during IUD placement, concluded that lidocaine-pilocarpine cream statistically significantly reduced pain at tenaculum placement compared with the placebo [16]. This systematic review compares the evidence available on local anesthetic agents and conscious sedation in intrauterine device insertion.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [17]. The literature search and screening plan were pre-established. The protocol for this systematic review has been registered on PROSPERO (CRD42023445050). Because this study was a systematic review, formal ethical approval was not required.

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The present review included randomized control trials that fulfilled the following criteria: (1) trials that examined conscious sedation for the management of IUD-insertion-related pain and discomfort, (2) trials that examined local anesthetic agents for IUD-insertion related to pain and discomfort, (3) trials that compared conscious sedation with standard pain management (local anesthetic agents). Case reports, series, and studies published in languages other than English were excluded.

To guide our research question and subsequent literature review, we employed a PICOS strategy. Our PICOS components were as follows: the population of interest is women undergoing intrauterine device (IUD) insertion; the intervention is conscious sedation administered during the procedure; the comparison group consists of those receiving local anesthetic agents for pain management during IUD insertion; and the primary outcome of interest is the reduction in pain and discomfort experienced by women during the procedure.

2.2. Literature Search Strategy

Articles were systematically searched within journals indexed in PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar (PERSONALIZATION), Clinical trials, and ProQuest, from inception to July 2023, using the following terms: (“IUD”) OR (“intrauterine device”) AND (“conscious sedation”) OR (“sedation”) OR (“nitrous oxide”) OR (“Entonox”) OR (“Local anesthetics”) OR (“opioid analgesics”) OR (“lidocaine”) OR (“misoprostol”). Retrieved citations were imported into an Excel Document.

2.3. Screening and Study Selection

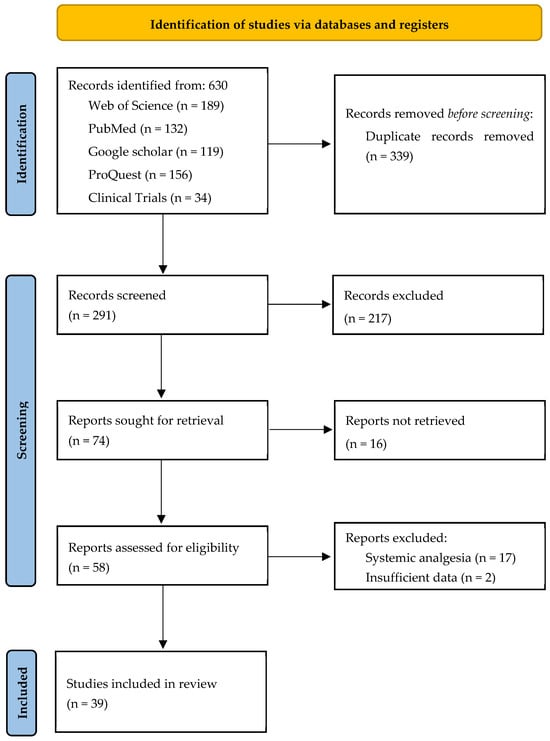

All records were imported into Rayyan Software 2025 to screen titles, abstracts, and select studies [18]. After removing duplicates using Rayyan software, two independent reviewers (E.M. and A.Z.) screened the title and abstract for relevance to the review. Disagreements concerning eligibility were discussed, and, when necessary, a third researcher was consulted and were resolved by consensus. In full-text, articles that met the eligibility criteria were retrieved and independently assessed for inclusion and exclusion criteria by two pairs of reviewers (R.T., A.Z., R.S., and E.M.). Both independent reviewers had to approve an article’s eligibility for inclusion. A flowchart has been developed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

2.4. Critical Appraisal

Bias Assessment

The Cochrane risk tool for bias was used to evaluate the quality of RCTs. The tool encompasses various domains, with each domain’s judgments contributing to an overall RoB2 judgment that spans five main domains. These domains are fixed, focusing on aspects of trial design, conduct, and reporting using a series of ‘signaling questions’ to elicit information relevant to the risk of bias. It is then judged using an algorithm, and the judgments can be ‘low’ (for all domains, the risk of bias is low), ‘some concerns’ (for at least one of the domains, there is some concern), or ‘high’ (for at least one domain, there is a high risk or some concerns for multiple domains). Two authors (E.M. and A.Z.) independently conducted the risk of bias assessment, and after consulting with senior authors (R.T. and R.S.), they resolved disagreements through consensus.

3. Results

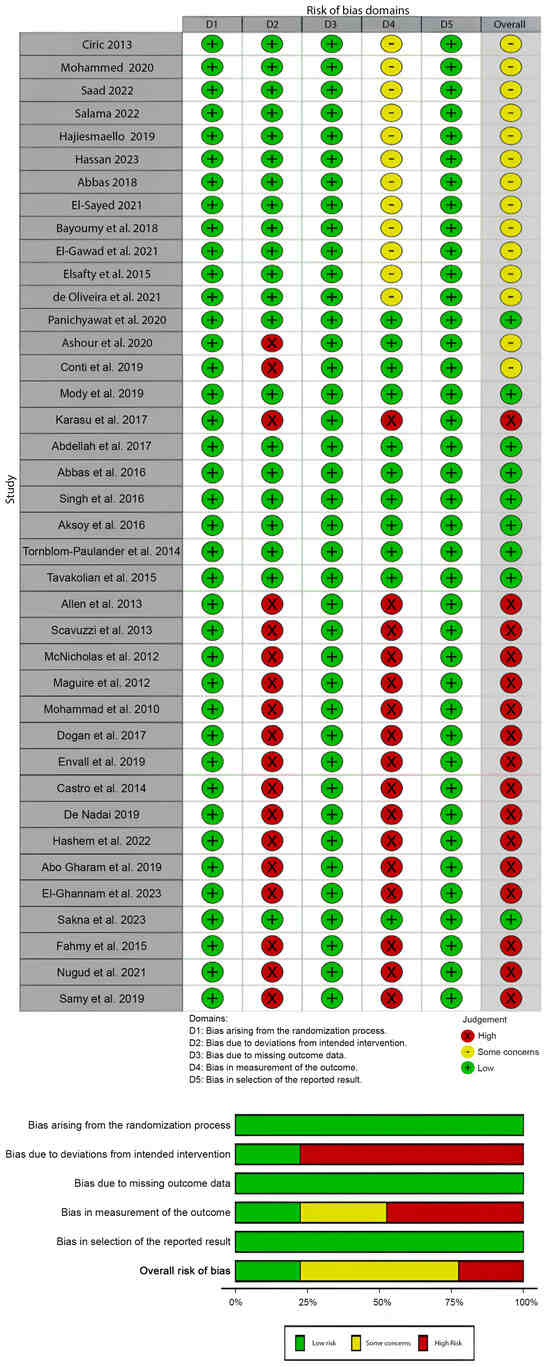

The risk of bias was assessed for all 39 articles included in this review, as shown in Figure 2. The studies conducted by Cirik et al. (2013), Mohammed et al. (2020), Saad et al. (2022), Salama et al. (2022), Hajiesmaello et al. (2019), Hassan et al. (2023), Abbas et al. (2018), El-Sayed et al. (2021), Bayoumy et al. (2018), Sakna et al. (2021), Elsafty et al. (2015), de Oliveira et al. (2021), Panichyawat et al. (2020), Mody et al. (2018), Karasu et al. (2017), Abdellah et al. (2017), Abbas et al. (2017), Singh et al. (2016), Aksoy et al. (2016), Tornblom-Paulander et al. (2014), Tavakolian et al. (2015), and Sakna et al. (2023) exhibited commendably low risks of bias across key domains [13,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

Figure 2.

Risk of bias assessment (ROB2) of included studies.

These studies have meticulously managed their randomization processes, ensuring a fair allocation of participants to intervention groups. They have adhered closely to the intended interventions, minimizing deviations that could affect the outcomes. Additionally, these studies have robust strategies for handling missing outcome data, reducing potential bias in result interpretation. The measurement of outcomes in these studies is well-defined and appropriately executed, minimizing the risk of biased assessments. Moreover, their reporting of results appears transparent and comprehensive, maintaining integrity in the reporting process. These studies stand out for their methodological rigor, contributing reliable evidence to the field.

Several studies, such as those from Ashour et al. (2020), Conti et al. (2019), Allen et al. (2013), Scavuzzi et al. (2013), McNicholas et al. (2012), Maguire et al. (2012), Charandabi et al. (2010), Dogan et al. (2017), Envall et al. (2019), Castro et al. (2014), De Nadai (2019), Hashem et al. (2022), EL-Gharib et al. (2019), El-Ghannam et al. (2023), Fahmy et al. (2015), Nugud et al. (2021), and Samy et al. (2019) display generally low risks of bias but raise some concerns in specific domains [16,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53]. While these studies maintain sound randomization processes, deviations from the intended interventions or variations in execution might affect outcome assessments. However, they have managed missing outcome data well, ensuring a minimal impact on the overall results. Despite these concerns, these studies maintain robust methodologies in outcome measurements, fostering reasonable confidence in their reported findings. It is crucial to note these concerns, but they do not significantly compromise the overall credibility of their results.

A subset of studies, including Karasu et al. (2017), Allen et al. (2013), Scavuzzi et al. (2013), McNicholas et al. (2012), Maguire et al. (2012), Charandabi et al. (2010), Dogan et al. (2017), Envall et al. (2019), Castro et al. (2014), De Nadai et al. (2019), Hashem et al. (2022), EL-Gharib et al. (2019), El-Ghannam et al. (2023), Fahmy et al. (2015), Nugud et al. (2021), and Samy et al. (2019), exhibit high risks of bias, primarily due to deviations from intended interventions and potential issues in outcome measurements [16,32,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53]. These studies encountered challenges in adhering strictly to the planned interventions or in precisely measuring outcomes, influencing their reported findings. Additionally, there are indications of potential biases in the selection of reported results, which could impact the interpretation of their conclusions. Consequently, these studies require careful consideration due to the higher likelihood of biased outcomes or interpretations.

Overall, while most of the studies uphold robust methodologies with low risks of bias, there is a subset with varying levels of concern or higher risks in specific domains. These nuances highlight the importance of critically appraising each study’s methodological approach, emphasizing the need to weigh evidence from studies with lower versus higher risks of bias when drawing conclusions or making recommendations regarding local anesthetic agents and conscious sedation in intrauterine device insertion.

The included studies, totaling 39, investigated various interventions to reduce pain during intrauterine device (IUD) insertion. The studies reflected a diverse geographic distribution, with research conducted in Turkey, Egypt, Iran, Brazil, Thailand, Japan, Sweden, and the United States. The research spanned from 2010 to 2023, and the study designs primarily comprised randomized controlled trials (RCTs), with a few employing double-blind, placebo-controlled trial designs. Sample sizes varied across studies, ranging from 60 to 302 participants, encompassing women within different age groups.

The participants’ characteristics in the included studies varied across interventions and comparisons, encompassing a diverse range of pain management strategies during IUD insertion. Sample sizes and age groups differed, reflecting the heterogeneous nature of the study populations. The interventions explored in these studies included the use of various medications such as lidocaine, misoprostol, naproxen, nitrous oxide, and diclofenac, administered through different routes, including vaginal, sublingual, spray, cream, and injection. The studies also evaluated the effectiveness of interventions in specific populations, including nulliparous women, women with a history of cesarean section, and those with anticipated complex loop application during copper IUD insertion. Additionally, the investigations compared different pain management strategies, such as lidocaine spray versus oral ibuprofen tablets and diclofenac versus misoprostol (Table 1).

Table 1.

General characteristics of the included studies (N = 39).

For instance, Cirik et al. (2013) evaluated the impact of 10 mL of 1% lidocaine for paracervical block compared to a placebo (0.9% NaCl solution) and a no-treatment group, focusing on pain perception during the paracervical block [19]. Mohammed et al. (2020) assessed different outcomes of IUD insertion with varying misoprostol doses administered vaginally or sublingually [20]. Saad et al. (2022) examined the effects of vaginal misoprostol on cervical ripening and successful IUD insertion compared to a placebo group [21]. Salama et al. (2022) explored the difficulty of Mirena IUD insertion and pain scores with different misoprostol doses, comparing them to a placebo group for Mirena IUD insertion [54].

Other studies investigated the effectiveness of lidocaine preparations, such as Bayoumy et al. (2018), who compared different local lidocaine formulations, i.e., lidocaine injection, lidocaine cream, and lidocaine spray for reducing pain sensation during IUCD insertion [26]. The study by Tornblom-Paulander et al. (2015) evaluated a novel lidocaine formulation against a placebo, measuring significantly lower pain scores with lidocaine [36]. Furthermore, studies like Aksoy et al. (2016) focused on the efficacy of 10% lidocaine spray compared to a placebo in reducing pain during IUD insertion [35]. (Table 2).

Table 2.

The participants’ characteristics in the included studies.

The included studies on pain management during intrauterine device (IUD) insertion demonstrated varied outcomes across success rate, ease of insertion, pain scores, and side effects. Several studies reported a significant reduction in pain perception during IUD insertion with different interventions. For instance, misoprostol, when administered vaginally, was associated with lower pain scores and increased success rates in studies conducted by Mohammed et al. (2020), Saad et al. (2022), and Salama et al. (2022) [20,21,54]. As a paracervical block, spray, or gel, lidocaine consistently demonstrated efficacy in reducing pain during IUD insertion, as reported by Cirik et al. (2013) and Hajiesmaello (2019) [19,22]. Moreover, a lidocaine intracervical block also reduced pain, according to De Nadai et al. (2019) [48].

In contrast, Singh et al. (2016) did not find significant pain reduction with nitrous oxide [13,33]. The study by Tornblom-Paulander et al. (2015) on a novel lidocaine formulation reported lower pain scores but noted similar adverse events in both the lidocaine and placebo groups [36]. Regarding the ease of insertion, interventions like misoprostol were associated with easier Mirena insertion in studies by Salama et al. (2022) and Hassan et al. (2023) [23,54].

However, El-Sayed (2021) noted a significant effect of timing on IUD insertion success with misoprostol [25]. Success rate was reported in six studies [20,21,25,26,27,51], in which success rate was significantly higher among those with interventional tools compared to control groups. Regarding side effects, studies consistently reported adverse events associated with certain interventions. For example, misoprostol was linked to increased nausea and vomiting in studies by Salama (2022), Sakna et al. (2021), and Hashem et al. (2022) [27,49,54]. Lidocaine, in its various forms, was associated with mild complications, including vasovagal reactions, nausea, vomiting, and dizziness, as reported by Aksoy et al. (2016), Panichyawat et al. (2020), and Tornblom-Paulander et al. (2015) [30,35,36] (Table 3).

Table 3.

The summary of the outcomes of the included studies.

4. Discussion

The present systematic review aimed to evaluate local anesthetic agents and conscious sedation use in intrauterine device (IUD) insertion. IUDs are highly effective long-acting reversible contraceptive methods that offer various advantages beyond contraception. However, pain and anxiety associated with IUD insertion remain significant barriers to their widespread acceptance and utilization. Therefore, this review sought to assess the available evidence on pain management strategies during IUD placement. In this comprehensive discussion, we explore various approaches to alleviate pain during IUD insertion, including conscious sedation, local anesthetics, misoprostol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and the association between reproductive factors and elevated pain.

4.1. Pain Reduction with Conscious Sedation

Conscious sedation is the administration of nitrous oxide or a combination of lidocaine and naproxen [56]. The use of conscious sedation during IUD insertion has been explored as a potential strategy to alleviate procedural discomfort. Studies, such as Singh et al. (2016) [13], investigated the efficacy of nitrous oxide and a combination of lidocaine and naproxen, respectively. However, the results were inconclusive, with no significant reduction in pain reported in these studies. Similar results were reported in studies not included in this systematic review [56,57,58]. This lack of consistent evidence raises questions about the effectiveness of conscious sedation in achieving optimal pain reduction during IUD insertion. It suggests that alternative approaches may need to be considered or that further research is required to refine the use of conscious sedation in this context.

4.2. Pain Reduction with Local Anesthetics

Local anesthetics, particularly lidocaine in various formulations, have been extensively studied for their potential in pain reduction during IUD insertion. Studies conducted by Cirik (2013), and Hajiesmaello (2019) consistently reported a significant decrease in pain perception with Lidocaine [19,22]. The findings highlight the efficacy of local anesthetics in achieving analgesia during IUD insertion [16,59]. The majority of included studies demonstrated lidocaine’s ability to reduce procedural pain when applied topically. The inclusion of multiple large, rigorous, randomized controlled trials provides compelling evidence that lidocaine effectively reduces pain from IUD insertion when applied topically [42]. Moreover, Aksoy et al. (2016) randomized 200 participants in their trial comparing lidocaine and placebo sprays. The sample sizes of these studies strengthen the validity and generalizability of their findings, demonstrating lidocaine spray’s analgesic properties [35].

Whether administered as a spray, gel, or injection, lidocaine has demonstrated its potential to enhance patient comfort during IUD insertion [32]. The choice of lidocaine formulation may depend on patient preference, procedural requirements, and the specific steps of IUD insertion that generate the most discomfort. Clinicians should consider these factors when tailoring pain management strategies to individual patient needs.

Misoprostol, a prostaglandin E1 analog, has been explored for its potential role in reducing pain during IUD insertion by promoting cervical ripening [41,60]. Studies conducted by Mohammed (2020), Saad (2022), and Salama (2022) reported a significant reduction in pain scores and increased success rates with the use of vaginal misoprostol [20,21,54].

However, achieving an optimal balance between efficacy and tolerability remains an area of active investigation since contradictory findings from studies such as Ashour et al. (2020) and Abdellah et al. (2017) raise questions about the consistent efficacy of misoprostol in pain reduction during IUD insertion since they observed potential for adverse effects like cramping [33,38]. Further research is warranted to establish standardized protocols and address the variability in outcomes.

4.3. The Effect of NSAIDs on IUD Insertion

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as naproxen, have been investigated for their potential in reducing pain during IUD insertion. Studies like de Oliveira et al. (2021) reported the effectiveness of naproxen in lowering pain scores during levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system insertion [29]. However, Fahmy et al. (2015) found no significant difference in pain intensity during IUD insertion compared to a placebo group [52]. A previous systematic review and meta-analysis showed that NSAIDs were not effective in reducing IUD-insertion-related pain, regardless of their type or dose [61]. While NSAIDs present a promising avenue for pain management, further research is needed to determine optimal dosages and their effectiveness in diverse populations.

4.4. Association Between Reproductive Factors and Elevated Pain in IUD Insertion

Various studies explored the association between reproductive factors and elevated pain during IUD insertion. El-Ghannam et al. (2023) suggested that the success of IUD insertion might be more influenced by the selected intervention, such as the use of vaginal misoprostol versus Dinoprostone, than solely reproductive factors [51]. Understanding the nuanced interplay between reproductive factors and pain perception during IUD insertion is crucial for tailoring pain management strategies to individual patient needs. Further research could provide valuable insights for personalized care during IUD insertion.

5. Limitations

Despite the valuable insights provided by the included studies, it is crucial to acknowledge several limitations that may impact the generalizability and interpretation of the findings. The heterogeneity in methodologies, including variations in interventions, routes of administration, and outcome measures, challenges direct comparisons across studies. The diverse study populations, with variations in age, parity, and gynecological history, hinder a comprehensive understanding of demographic influences on pain perception during IUD insertion. Limited long-term follow-up data on patient satisfaction and adverse events restrict the assessment of sustained intervention impact. Inconsistent reporting of adverse events and the potential for publication bias raise concerns about the safety profile and potential overestimating specific interventions’ efficacy. The lack of standardized pain assessment tools and exploration of patient preferences further highlight areas for improvement in future research. The lack of specific patient characteristics such as parity, timing of the last menstrual period, previous gynecological interventions, and insertion techniques could provide further insights. Moreover, no differences according to IUD type have been reported. Furthermore, the influence of different IUD types on pain and outcomes was not distinguished in our analysis. These factors are critical for comprehending variations in outcomes and warrant exploration in future research. Addressing these limitations is essential for refining pain management strategies during IUD insertion and ensuring patient-centered care.

6. Conclusions

In alignment with our findings, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) does not recommend the routine application of Misoprostol for intrauterine device (IUD) placement. It is recommended mainly for individuals with a history of unsuccessful insertions. Nevertheless, the CDC advocates for the use of lidocaine, whether delivered via a paracervical block or as a topical application, to alleviate patient discomfort. [62]

While conscious sedation has shown limited efficacy, local anesthetics, misoprostol, and NSAIDs present promising avenues for pain reduction during IUD insertion. Tailoring interventions based on patient characteristics and further investigation into standardized protocols are essential for optimizing pain management strategies in clinical practice. Additionally, exploring the interplay between reproductive factors and pain perception can provide valuable insights for personalized care during IUD insertion. Further studies should take patients’ education into consideration as potential factors to reduce pain.

7. Suggestions

Future research is recommended to focus on the standardization of protocols, the conduction of direct comparisons, and the investigation of combination therapies to address existing evidence gaps and improve pain management during the insertion of intrauterine devices (IUDs).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A.; methodology, R.A. and E.A.; formal analysis, R.A. and L.A (Lama Alzelfawi); Screening, R.A., R.B.S. and A.A. (Alya AlZabin); data extraction, E.A., R.A. and A.Z; writing—original draft preparation, R.A., R.B.S. and E.A.; writing—review and editing, L.A. (Lamya Almusharaf) and W.A.; visualization, R.A.; supervision, R.A. and A.A. (Amer Alkinani).; project administration, R.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Espey, E.; Ogburn, T. Long-acting reversible contraceptives: Intrauterine devices and the contraceptive implant. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 117, 705–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speidel, J.J.; Harper, C.C.; Shields, W.C. The potential of long-acting reversible contraception to decrease unintended pregnancy. Contraception 2008, 78, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laporte, M.; Metelus, S.; Ali, M.; Bahamondes, L. Major differences in the characteristics of users of the copper intrauterine device or levonorgestrel intrauterine system at a clinic in Campinas, Brazil. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 156, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trussell, J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception 2011, 83, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoost, J. Understanding benefits and addressing misperceptions and barriers to intrauterine device access among populations in the United States. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2014, 8, 947–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Adeyemi-Fowode, O.A.; Bercaw-Pratt, J.L. Intrauterine Devices: Effective Contraception with Noncontraceptive Benefits for Adolescents. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2019, 32, S2–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, T.A.; Sonalkar, S.; Schreiber, C.A.; Perriera, L.K.; Sammel, M.D.; Akers, A.Y. Anticipated Pain During Intrauterine Device Insertion. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2020, 33, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akdemir, Y.; Karadeniz, M. The relationship between pain at IUD insertion and negative perceptions, anxiety and previous mode of delivery. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2019, 24, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myo, M.G.; Nguyen, B.T. Intrauterine Device Complications and Their Management. Curr. Obstet. Gynecol. Rep. 2023, 12, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjos, F.C.Q.S.; Marcelino, A.C.; Espejo-Arce, X.; Pereira, P.d.C.; Barbosa, P.F.; Juliato, C.T.; Bahamondes, L. Pain and ease of insertion of three different intrauterine devices in Brazilian adolescents: A participant-blinded randomized trial. Contraception 2023, 122, 109997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marions, L.; Lövkvist, L.; Taube, A.; Johansson, M.; Dalvik, H.; Øverlie, I. Use of the levonorgestrel releasing-intrauterine system in nulliparous women—A non-interventional study in Sweden. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2011, 16, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamondes, L.; Mansour, D.; Fiala, C.; Kaunitz, A.M.; Gemzell-Danielsson, K. Practical advice for avoidance of pain associated with insertion of intrauterine contraceptives. J. Fam. Plan. Reprod. Health Care 2014, 40, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.H.; Thaxton, L.; Carr, S.; Leeman, L.; Schneider, E.; Espey, E. A randomized controlled trial of nitrous oxide for intrauterine device insertion in nulliparous women. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2016, 135, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, L.M.; Bernholc, A.; Zeng, Y.; Allen, R.H.; Bartz, D.; A O’Brien, P.; Hubacher, D. Interventions for pain with intrauterine device insertion. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD007373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Lopez, F.R.; Martinez-Dominguez, S.J.; Perez-Roncero, G.R.; Hernandez, A.V. Uterine or paracervical lidocaine application for pain control during intrauterine contraceptive device insertion: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2018, 23, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samy, A.; Abdelhakim, A.M.; Latif, D.; Hamza, M.; Osman, O.M.; Metwally, A.A. Benefits of vaginal dinoprostone administration prior to levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system insertion in women delivered only by elective cesarean section: A randomized double-blinded clinical trial. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 301, 1463–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirik, D.; Taskin, E.; Tuglu, A.; Ortac, A.; Dai, O. Paracervical block with 1% lidocaine for pain control during intrauterine device insertion: A prospective, single-blinded, controlled study. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 2, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mohammed, N.; Mohammed, N.H.; El-Rahman, Y.M. Vaginal or sublingual misoprostol before insertion of an intrauterine device in women who have previously had a cesarean section. Sci. J. Al-Azhar Med. Fac. Girls 2019, 3, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, A.E.S.; Soliman, E.E.A.; Negm, O.M.L. Role of vaginal misoprostol before intrauterine device insertion. Menoufia Med. J. 2022, 35, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajiesmaello, M.; Mohammadi, E.; Farrokh-Eslamlou, H. Evaluation of the effect of 10% lidocaine spray on reducing the pain of intrauterine device insertion: A randomised controlled trial. S. Afr. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Zalat, Y.; Abdou, H. Efficacy of misoprostol in reducing the time and easiness the insertion of Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device; Randomized controlled trial. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. J. 2023, 14, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.M.; Ragab, E.; Ali, S.S.; Shady, N.W.; Sallam, H.F.; Sabra, A.M. Does lidocaine gel produce an effective analgesia prior to copper IUD insertion? Randomized clinical trial. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 7, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mohamed El-Sayed, A.; Fawzy Mohamed, M.; Khamis Galal, S. Using of Misoprostol Vaginally Prior To Intrauterine Contraceptive Device Insertion Following Previous Insertion Failure: Randomized Clinical Trial. Al-Azhar Med. J. 2021, 50, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayoumy, H.A.; El-Hawwary, G.E.S.; Fouad, H.A.E.S. Lidocaine for Pain Control during Intrauterine Contraceptive Device Insertion: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Egypt. J. Hosp. Med. 2018, 73, 6010–6020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakna, N.; Gawad, M.A.E.; Elshahid, E.; Atik, A. Vaginal Misoprostol Prior to Intrauterine Contraceptive Device Insertion in Women Who Delivered Only by Elective Caeserean Section: Randomized Clinical Trial. Evid. Based Women’s Health J. 2020, 11, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsafty, M.S.E.; Ibrahim, M.E.; Hassanin, A.S.; Elyan, A.; Emeira, M.I. Does lidocaine 10% spray reduce pain during intrauterine contraceptive device insertion? A pilot randomized controlled clinical trial. Evid. Based Womenʼs Health J. 2015, 5, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, E.C.F.; Baêta, T.; Brant, A.P.C.; Silva-Filho, A.; Rocha, A.L.L. Use of naproxen versus intracervical block for pain control during the 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system insertion in young women: A multivariate analysis of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Womens Health 2021, 21, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panichyawat, N.; Mongkornthong, T.; Wongwananuruk, T.; Sirimai, K. 10% lidocaine spray for pain control during intrauterine device insertion: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. BMJ Sex. Reprod. Health 2021, 47, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mody, S.K.; Farala, J.P.; Jimenez, B.; Nishikawa, M.; Ngo, L.L. Paracervical Block for Intrauterine Device Placement Among Nulliparous Women. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 132, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasu, Y.; Cömert, D.K.; Karadağ, B.; Ergün, Y. Lidocaine for pain control during intrauterine device insertion. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2017, 43, 1061–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellah, M.S.; Abbas, A.M.; Hegazy, A.M.; El-Nashar, I.M. Vaginal misoprostol prior to intrauterine device insertion in women delivered only by elective cesarean section: A randomized double-blind clinical trial. Contraception 2017, 95, 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.M.; Abdellah, M.S.; Khalaf, M.; Abdellah, N.H.; Ali, M.K.; Abdelmagied, A.M. Effect of cervical lidocaine–prilocaine cream on pain perception during copper T380A intrauterine device insertion among parous women: A randomized double-blind controlled trial. Contraception 2017, 95, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, H.; Aksoy, Ü.; Ozyurt, S.; Açmaz, G.; Babayigit, M. Lidocaine 10% spray to the cervix reduces pain during intrauterine device insertion: A double-blind randomised controlled trial. J. Fam. Plan. Reprod. Health Care 2016, 42, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tornblom-Paulander, S.; Tingåker, B.K.; Werner, A.; Liliecreutz, C.; Conner, P.; Wessel, H.; Ekman-Ordeberg, G. Novel topical formulation of lidocaine provides significant pain relief for intrauterine device insertion: Pharmacokinetic evaluation and randomized placebo-controlled trial. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 103, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavakolian, S.; Doulabi MA hmadi Baghban AA kbarzade Mortazavi, A.; Ghorbani, M. Lidocaine-Prilocaine Cream as Analgesia for IUD Insertion: A Prospective, Randomized, Controlled, Triple Blinded Study. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2015, 7, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashour, A.S.A.; El Sharkawy, M.; Ali, A.S.; Keshta, N.H.A.; Shatat, H.B.A.E.; El Mahy, M. Comparative Efficacy of Vaginal Misoprostol vs. Vaginal Dinoprostone Administered 3 Hours Prior to Copper T380A Intrauterine Device Insertion in Nulliparous Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2020, 33, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, J.A.; Lerma, K.; Schneyer, R.J.; Hastings, C.V.; Blumenthal, P.D.; Shaw, K.A. Self-administered vaginal lidocaine gel for pain management with intrauterine device insertion: A blinded, randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 220, 177.e1–177.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.H.; Raker, C.; Goyal, V. Higher dose cervical 2% lidocaine gel for IUD insertion: A randomized controlled trial. Contraception 2013, 88, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scavuzzi, A.; Souza, A.S.R.; Costa, A.A.R.; Amorim, M.M.R. Misoprostol prior to inserting an intrauterine device in nulligravidas: A randomized clinical trial. Human. Reprod. 2013, 28, 2118–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNicholas, C.P.; Madden, T.; Zhao, Q.; Secura, G.; Allsworth, J.E.; Peipert, J.F. Cervical lidocaine for IUD insertional pain: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 207, 384.e1–384.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, K.; Davis, A.; Rosario Tejeda, L.; Westhoff, C. Intracervical lidocaine gel for intrauterine device insertion: A randomized controlled trial. Contraception 2012, 86, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi, S.; Seidi, S.; Kazemi, F. Effect of lidocaine gel on pain from copper IUD insertion: A randomized double-blind controlled trial. Indian. J. Med. Sci. 2010, 64, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogan, S.; Simsek, B. Paracervical block and paracetamol for pain reduction during IUD insertion: A randomized controlled study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, QC09–QC11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Envall, N.; Lagercrantz, H.G.; Sunesson, J.; Kopp Kallner, H. Intrauterine mepivacaine instillation for pain relief during intrauterine device insertion in nulliparous women: A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Contraception 2019, 99, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, T.V.B.; Franceschini, S.A.; Poli-Neto, O.; Ferriani, R.A.; Silva De Sá, M.F.; Vieira, C.S. Effect of intracervical anesthesia on pain associated with the insertion of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in women without previous vaginal delivery: A RCT. Human. Reprod. 2014, 29, 2439–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nadai, M.N.; Poli-Neto, O.B.; Franceschini, S.A.; Yamaguti, E.M.; Monteiro, I.M.; Troncon, J.K.; Juliato, C.R.; Santana, L.F.; Bahamondes, L.; Vieira, C.S. Intracervical block for levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system placement among nulligravid women: A randomized double-blind controlled trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 222, 245.e1–245.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, A.T.; Mahmoud, M.; Aly Islam, B.; Eid, M.I.; Ahmed, N.; Mamdouh, A.M.; Elkomy, R.; Elgamel, A.F.; Hamada, A.A.A.; Khalil, E.M.; et al. Comparative efficacy of lidocaine–prilocaine cream and vaginal misoprostol in reducing pain during levonorgestrel intrauterine device insertion in women delivered only by cesarean delivery: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 165, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EL-Gharib, M.N. Effect of Diclofenac Versus Misoprostol on Pain Perception During Copper IUD Insertion in Cases of Stenosed Cervix. Gynecol. Obstet. Open Access Open J. 2019, I, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ghannam, E.H.; Elbasiony, H.R.; Dawood, A.E.G.S.; El-Namory, M.M. Vaginal misoprostol versus dinoprostone before copper IUD application in women with anticipated difficult loop application. Int. J. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2023, 7, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, M.; El Khouly, N.; Dawood, R.; Radwan, M. Comparison of 1% lidocaine paracervical block and NSAIDs in reducing pain during intrauterine device insertion. Menoufia Med. J. 2016, 29, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beheiry, M.M.M.; Mowafy, H.E.M.; Nugud, A.I.M.; Khalil, S.A.I. Effect of diclofenac versus misoprostol on pain perception during intrauterine contraceptive device insertion. Egypt. J. Hosp. Med. 2021, 84, 2208–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, S.; ElTemamy, E.; Abdel-Rasheed, M.; Salama, E. Role of vaginal misoprostol prior to levonorgestrel-releasing IUD insertion. Al-Azhar Int. Med. J. 2022, 3, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakna, N.A.; Elkadi, M.A.; Ghaly, M.R.A.; Khedr, A.H.M. Lidocaine Spray 10% versus Oral Ibuprofen Tablets in Pain Control during Copper Intrauterine Device Insertion (A Randomized Controlled Trial). Egypt. J. Hosp. Med. 2023, 91, 4110–4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, L.L.; Braaten, K.P.; Eichen, E.; Fortin, J.; Maurer, R.; Goldberg, A.B. Naproxen Sodium for Pain Control with Intrauterine Device Insertion. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 128, 1306–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chor, J.; Bregand-White, J.; Golobof, A.; Harwood, B.; Cowett, A. Ibuprofen prophylaxis for levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system insertion: A randomized controlled trial. Contraception 2012, 85, 558–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubacher, D.; Reyes, V.; Lillo, S.; Zepeda, A.; Chen, P.L.; Croxatto, H. Pain from copper intrauterine device insertion: Randomized trial of prophylactic ibuprofen. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 195, 1272–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercier, R.J.; Zerden, M.L. Intrauterine Anesthesia for Gynecologic Procedures. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 120, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, L.B.; Nguyen, A.; Snyder, E.; Kapp, N.; Ti, A.; Whiteman, M.K.; Curtis, K.M. Misoprostol for intrauterine device placement. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 2022, CD015584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samy, A.; Abbas, A.M.; Mahmoud, M.; Taher, A.; Awad, M.H.; El Husseiny, T.; Hussein, M.; Ramadan, M.; Shalaby, M.A.; El Sharkawy, M.; et al. Evaluating different pain lowering medications during intrauterine device insertion: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Fertil. Steril. 2019, 111, 553–561.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, K.M.; Nguyen, A.T.; Tepper, N.K.; Zapata, L.B.; Snyder, E.M.; Hatfield-Timajchy, K.; Kortsmit, K.; Cohen, M.A.; Whiteman, M.K. U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2024. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2024, 73, 1–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).