Beyond Drive for Thinness: Drive for Leanness in Anorexia Nervosa Prevention and Recovery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Refeeding Programs and AN Recovery

“Respondents reiterated again and again the importance of the mental components of AN in recovery, which they believe are underappreciated through hyper-focus on the body.”

4. Female Body Ideals and Drive for Leanness

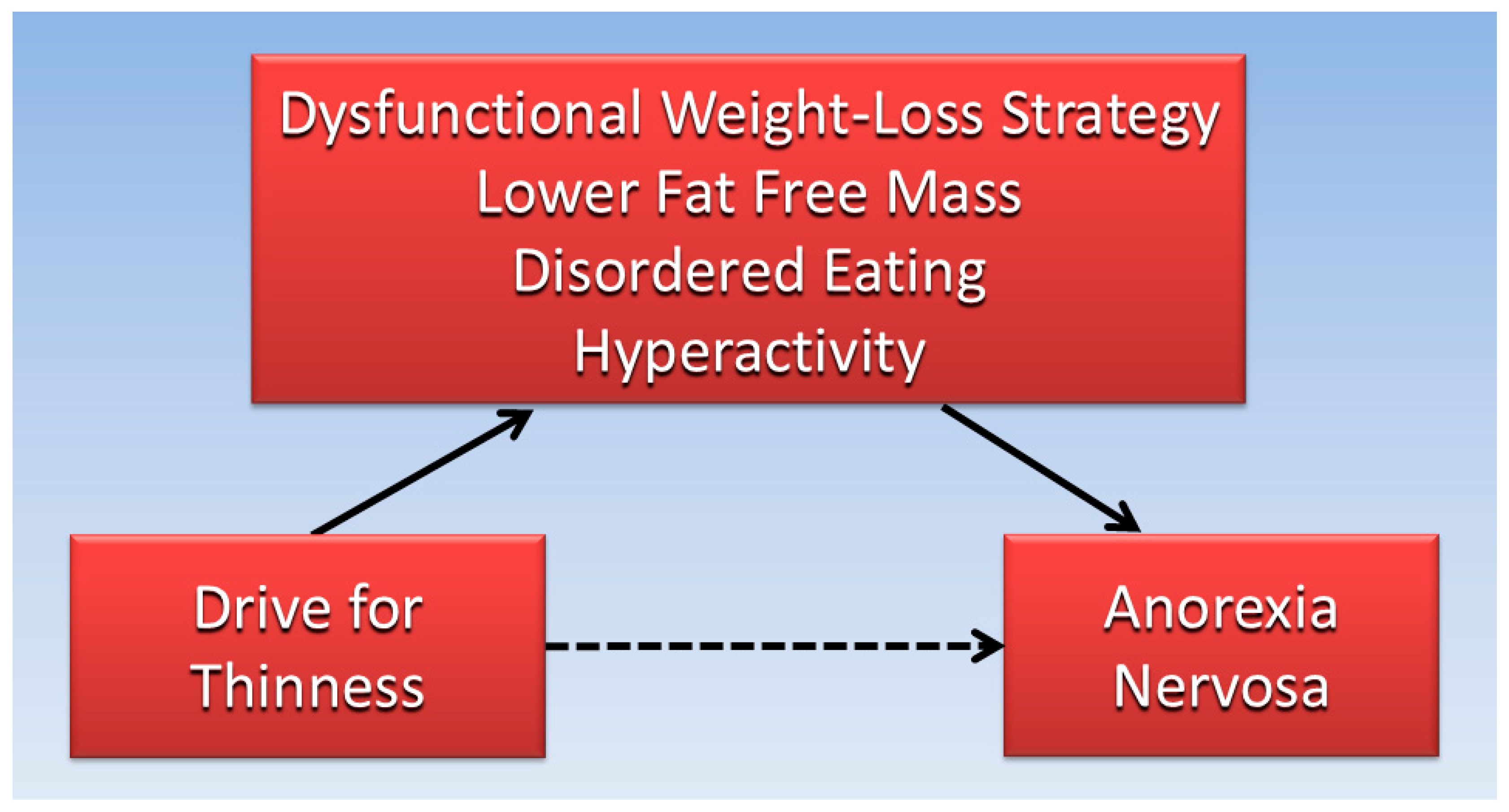

“‘Drive for Leanness’ refers to a motivating interest in having relatively low body fat and toned, physically fit muscles. The desire for limited body fat is not the equivalent of wanting to be thin [17].”

5. Body-Composition Estimates

6. Fat-Free Mass Index

7. Physical Activity and Weight-Management Programs for AN

“On average, a woman should eat 2000 calories daily to maintain her weight and limit her caloric intake to 1500 or less to lose 1 pound per week. To maintain his body weight, the average male should eat 2500 calories per day, or 2000 a day, if he wants to lose 1 pound per week.”

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. What are Eating Disorders? Available online: https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/eating-disorders/what-are-eating-disorders (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kaye, W.H.; Bulik, C.M. Treatment of Patients With Anorexia Nervosa in the US—A Crisis in Care. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 591–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miskovic-Wheatley, J.; Bryant, E.; Ong, S.H.; Vatter, S.; Le, A.; Aouad, P.; Barakat, S.; Boakes, R.; Brennan, L.; Bryant, E.; et al. Eating disorder outcomes: Findings from a rapid review of over a decade of research. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 11, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Ramírez-Goerke, M.I.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Ramos-Campo, D.J.; Navarro-Jiménez, E.; Yáñez-Sepúlveda, R.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. The Impact of Anorexia Nervosa and the Basis for Non-Pharmacological Interventions. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krug, I.; Binh Dang, A.; Granero, R.; Agüera, Z.; Sánchez, I.; Riesco, N.; Jimenez-Murcia, S.; Menchón, J.M.; Fernandez-Aranda, F. Drive for thinness provides an alternative, more meaningful, severity indicator than the DSM-5 severity indices for eating disorders. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2021, 29, 482–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, D.M. Eating Disorder Inventory-3 (EDI-3); Professional manual; Psychological Assessment Resources: Odessa, FL, USA, 2004; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Garner, D.M. Eating Disorder Inventory-3 (EDI-3) Scale Descriptions. Available online: https://toledocenter.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/EDI-3-Scale.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Tinsley, G.M.; Heymsfield, S.B. Fundamental Body Composition Principles Provide Context for Fat-Free and Skeletal Muscle Loss With GLP-1 RA Treatments. J. Endocr. Soc. 2024, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, M.; Sammarco, R.; De Filippo, E.; Caldara, A.; Speranza, E.; Scalfi, L.; Contaldo, F.; Pasanisi, F. Prediction of body composition in anorexia nervosa: Results from a retrospective study. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 1670–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.C.; Haroun, D.; Williams, J.E.; Nicholls, D.; Darch, T.; Eaton, S.; Fewtrell, M.S. Body composition in young female eating-disorder patients with severe weight loss and controls: Evidence from the four-component model and evaluation of DXA. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 69, 1330–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Military Nutrition Research. Body Composition and Physical Performance: Applications For the Military Services. In Body Composition and Physical Performance: Applications for the Military Services; Marriott, B.M., Grumstrup-Scott, J., Eds.; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Fleck, S.J. Body composition of elite American athletes. Am. J. Sports Med. 1983, 11, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Last, J.M. Dictionary of epidemiology. CMAJ Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1993, 149, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, M.; Giovannucci, E. Chapter 6–Nutritional Epidemiology. In Nutritional Oncology, 2nd ed.; Heber, D., Ed.; Academic Press: Burlington, VT, USA, 2006; pp. 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, A.; Ali, T.; Nazir, Z.; Mahfooz, A.; Inayat, Q.-u.-A.; Haque, M.A. Unintended consequences of dieting: How restrictive eating habits can harm your health. Int. J. Surg. Open 2023, 60, 100703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolak, L.; Murnen, S.K. Drive for leanness: Assessment and relationship to gender, gender role and objectification. Body Image 2008, 5, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanItallie, T.B.; Yang, M.U.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Funk, R.C.; Boileau, R.A. Height-normalized indices of the body’s fat-free mass and fat mass: Potentially useful indicators of nutritional status. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1990, 52, 953–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neeland, I.J.; McGuire, D.K.; Eliasson, B.; Ridderstråle, M.; Zeller, C.; Woerle, H.J.; Broedl, U.C.; Johansen, O.E. Comparison of Adipose Distribution Indices with Gold Standard Body Composition Assessments in the EMPA-REG H2H SU Trial: A Body Composition Sub-Study. Diabetes Ther. 2015, 6, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfswinkel, J.F.; Furtmueller, E.; Wilderom, C.P.M. Using grounded theory as a method for rigorously reviewing literature. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2013, 22, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Martini, M.; Lepora, M.; Longo, P.; Amodeo, L.; Marzola, E.; Abbate-Daga, G. Anorexia Nervosa in the Acute Hospitalization Setting. In Eating Disorders; Patel, V., Preedy, V., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Khalsa, S.S.; Portnoff, L.C.; McCurdy-McKinnon, D.; Feusner, J.D. What happens after treatment? A systematic review of relapse, remission, and recovery in anorexia nervosa. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, C.; de la Fontaine, L.; Winter, B.; Müller, N.; Schaub, A.; Früstück, C.; Schüle, C.; Voderholzer, U.; Cuntz, U.; Falkai, P.; et al. First results of a refeeding program in a psychiatric intensive care unit for patients with extreme anorexia nervosa. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, G. Skinny blues: Karen Carpenter, anorexia nervosa and popular music. Pop. Music 2018, 37, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haithman, D. A TV Movie He Didn’t Want: Brother Richard Guides CBS’ ‘Karen Carpenter Story’; Los Angeles Times: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ramjan, L.M.; Fogarty, S. Clients’ perceptions of the therapeutic relationship in the treatment of anorexia nervosa: Qualitative findings from an online questionnaire. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2019, 25, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasofer, D.R.; Lemly, D.C.; Lloyd, C.; Jablonski, M.; Schaefer, L.M.; Wonderlich, S.A.; Attia, E. Evaluation of an online modular eating disorders training (PreparED) to prepare healthcare trainees: A survey study. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, C.; Ogden, J. Managing patients with eating disorders: A qualitative study in primary care. BJGP Open 2024, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, E.; Carrera, O. Severe and Enduring Anorexia Nervosa: Enduring Wrong Assumptions? Front. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 538997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barko, E.B.; Moorman, S.M. Weighing in: Qualitative explorations of weight restoration as recovery in anorexia nervosa. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesse-Biber, S. Am I Thin Enough Yet? The Cult of Thinness and the Commercialization of Identity; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bozsik, F.; Whisenhunt, B.L.; Hudson, D.L.; Bennett, B.; Lundgren, J.D. Thin Is In? Think Again: The Rising Importance of Muscularity in the Thin Ideal Female Body. Sex Roles 2018, 79, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, B.; Rancourt, D. Drive for leanness: Potentially less maladaptive compared to drives for thinness and muscularity. Eat. Weight Disord. 2020, 25, 1213–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlenburg, S.C.; Gleaves, D.H.; Hutchinson, A.D. Anorexia nervosa and perfectionism: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2019, 52, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faija, C.L.; Tierney, S.; Gooding, P.A.; Peters, S.; Fox, J.R.E. The role of pride in women with anorexia nervosa: A grounded theory study. Psychol. Psychother. 2017, 90, 567–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westmoreland, P.; Johnson, C.; Stafford, M.; Martinez, R.; Mehler, P.S. Involuntary Treatment of Patients With Life-Threatening Anorexia Nervosa. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law Online 2017, 45, 419–425. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, C.R. The Official YMCA Physical Fitness Handbook; Popular Library: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Wilmore, J.H.; Behnke, A.R. An anthropometric estimation of body density and lean body weight in young men. J. Appl. Physiol. 1969, 27, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilmore, J.H.; Behnke, A.R. An anthropometric estimation of body density and lean body weight in young women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1970, 23, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofstad, A.P.; Sommer, C.; Birkeland, K.I.; Bjørgaas, M.R.; Gran, J.M.; Gulseth, H.L.; Johansen, O.E. Comparison of the associations between non-traditional and traditional indices of adiposity and cardiovascular mortality: An observational study of one million person-years of follow-up. Int. J. Obes. 2019, 43, 1082–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Visvanathan, T.; Field, J.; Ward, L.C.; Chapman, I.; Adams, R.; Wittert, G.; Visvanathan, R. Lean body mass: The development and validation of prediction equations in healthy adults. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcus, J. Chapter 10–Weight Management: Finding the Healthy Balance: Practical Applications for Nutrition, Food Science and Culinary Professionals. In Culinary Nutrition; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 431–473. [Google Scholar]

- Jeukendrup, A.; Gleeson, M. Sport Nutrition, 4th ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Plank, L.D.; Hill, G.L. 58–Body Composition. In Surgical Research; Souba, W.W., Wilmore, D.W., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2001; pp. 797–812. [Google Scholar]

- Sanvictores, T.; Casale, J.; Huecker, M.R. Physiology, Fasting. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, M.; Gibbons, C.; Blundell, J. Fat-free mass and resting metabolic rate are determinants of energy intake: Implications for a theory of appetite control. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2023, 378, 20220213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmiski, L.; Schmiege, S.J.; Mascolo, M.; Gaudiani, J.; Mehler, P.S. Chronic starvation secondary to anorexia nervosa is associated with an adaptive suppression of resting energy expenditure. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 908–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, A.S.; Novitskaya, M.; Treuth, A.L. Predictive Equations Overestimate Resting Metabolic Rate in Survivors of Chronic Stroke. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 103, 1352–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frostad, S.; Rozakou-Soumalia, N.; Dârvariu, Ş.; Foruzesh, B.; Azkia, H.; Larsen, M.P.; Rowshandel, E.; Sjögren, J.M. BMI at Discharge from Treatment Predicts Relapse in Anorexia Nervosa: A Systematic Scoping Review. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinspoon, S.; Thomas, L.; Miller, K.; Pitts, S.; Herzog, D.; Klibanski, A. Changes in regional fat redistribution and the effects of estrogen during spontaneous weight gain in women with anorexia nervosa123. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 73, 865–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orphanidou, C.I.; McCargar, L.J.; Birmingham, C.L.; Belzberg, A.S. Changes in body composition and fat distribution after short-term weight gain in patients with anorexia nervosa. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 65, 1034–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalfi, L.; Polito, A.; Bianchi, L.; Marra, M.; Caldara, A.; Nicolai, E.; Contaldo, F. Body composition changes in patients with anorexia nervosa after complete weight recovery. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 56, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauty, M.; Menu, P.; Jolly, B.; Lambert, S.; Rocher, B.; Le Bras, M.; Jirka, A.; Guillot, P.; Pretagut, S.; Fouasson-Chailloux, A. Inpatient Rehabilitation during Intensive Refeeding in Severe Anorexia Nervosa. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, U.G.; Schutz, Y.; Dupertuis, Y.M.; Pichard, C. Body composition interpretation: Contributions of the fat-free mass index and the body fat mass index. Nutrition 2003, 19, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudsk, K.A.; Munoz-Del-Rio, A.; Busch, R.A.; Kight, C.E.; Schoeller, D.A. Stratification of Fat-Free Mass Index Percentiles for Body Composition Based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III Bioelectric Impedance Data. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2017, 41, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, C.P.; Green, K. Hospitalized anorexics and resistance training: Impact on body composition and psychological well-being. A preliminary study. Eat. Weight Disord. 2002, 7, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osilla, E.V.; Safadi, A.O.; Sharma, S. Calories. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Slater, G.J.; Dieter, B.P.; Marsh, D.J.; Helms, E.R.; Shaw, G.; Iraki, J. Is an Energy Surplus Required to Maximize Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy Associated With Resistance Training. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R. The Body Fat Guide; Healthstyle Publications: Kitchener, ON, CA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Toutain, M.; Gauthier, A.; Leconte, P. Exercise therapy in the treatment of anorexia nervosa: Its effects depending on the type of physical exercise-A systematic review. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 939856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achamrah, N.; Coëffier, M.; Déchelotte, P. Physical activity in patients with anorexia nervosa. Nutr. Rev. 2016, 74, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beumont, P.J.; Arthur, B.; Russell, J.D.; Touyz, S.W. Excessive physical activity in dieting disorder patients: Proposals for a supervised exercise program. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1994, 15, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteelandt, K.; Rijmen, F.; Pieters, G.; Probst, M.; Vanderlinden, J. Drive for thinness, affect regulation and physical activity in eating disorders: A daily life study. Behav. Res. Ther. 2007, 45, 1717–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansas State University. Physical Activity and Controlling Weight. Available online: https://www.k-state.edu/paccats/Contents/PA/PDF/Physical%20Activity%20and%20Controlling%20Weight.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; U.S. Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2005; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2005.

- Breithaupt, L.; Eickman, L.; Byrne, C.E.; Fischer, S. REbeL Peer Education: A model of a voluntary, after-school program for eating disorder prevention. Eat. Behav. 2017, 25, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| A. | “Restriction of energy intake relative to requirements, leading to a significantly low bodyweight in the context of age, sex, developmental trajectory, and physical health. Significantly low weight is defined as a weight that is less than minimally normal or, for children and adolescents, less than that minimally expected.” |

| B. | “Intense fear of gaining weight or of becoming fat, or persistent behavior that interferes with weight gain, even though at a significantly low weight.” |

| C. | “Disturbance in the way in which one’s bodyweight or shape is experienced, undue influence of bodyweight or shape on self-evaluation, or persistent lack of recognition of the seriousness of the current low bodyweight.” |

| Drive for Leanness Scale |

|---|

| 1. I think the best-looking bodies are well-toned. |

| 2. When a person’s body is hard and firm, it says they are well-disciplined. |

| 3. My goal is to have well-toned muscles. |

| 4. Athletic-looking people are the most attractive people. |

| 5. It is important to have well-defined abs. |

| 6. People with well-toned muscles look good in clothes. |

| Activity | Calories |

|---|---|

| Aerobics | 187 |

| Bicycling (<10 mph) | 113 |

| Bicycling (>10 mph) | 230 |

| Dancing | 129 |

| Hiking | 144 |

| Running/jogging (5 mph) | 230 |

| Stretching | 70 |

| Swimming (slow freestyle laps) | 199 |

| Walking (3.5 mph) | 109 |

| Walking (4.5 mph) | 175 |

| Weightlifting (general light workout) | 86 |

| Weightlifting (vigorous effort) | 171 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brown, R.B. Beyond Drive for Thinness: Drive for Leanness in Anorexia Nervosa Prevention and Recovery. Women 2024, 4, 529-540. https://doi.org/10.3390/women4040039

Brown RB. Beyond Drive for Thinness: Drive for Leanness in Anorexia Nervosa Prevention and Recovery. Women. 2024; 4(4):529-540. https://doi.org/10.3390/women4040039

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrown, Ronald B. 2024. "Beyond Drive for Thinness: Drive for Leanness in Anorexia Nervosa Prevention and Recovery" Women 4, no. 4: 529-540. https://doi.org/10.3390/women4040039

APA StyleBrown, R. B. (2024). Beyond Drive for Thinness: Drive for Leanness in Anorexia Nervosa Prevention and Recovery. Women, 4(4), 529-540. https://doi.org/10.3390/women4040039