Women’s Perspectives on Black Infant Mortality in the United States

Abstract

1. Introduction

Aim

2. Results

2.1. Qualitative Analysis of Results

2.1.1. Access to Care

“Access to equitable healthcare; OB deserts.”White, 30 y/o, Indiana.

“Lack of access to prenatal care, systemic racism, bias in the healthcare system.”White, 47 y/o, Indiana.

“More support for mothers post-birth.”Black, 19 y/o, Florida.

“Create more free, healthcare clinics for prenatal care and pregnancy for women.”White, 50 y/o, Indiana.

“Legislation to address IM and accessibility to equitable healthcare.”White, 30 y/o, Indiana.

2.1.2. Sleeping Issues

“Unintentional suffocation in unsafe sleep environments.”Biracial or Multiracial, 46 y/o, Indiana.

“SIDS, congenital defects, preterm birth.”White, 23 y/o, Indiana.

“Follow the ABCs of safe sleep: Alone, Back, Crib.”White, 24 y/o, Indiana.

“Educating Black women more and providing more resources for postpartum professional and childcare support. Especially for low-income and working-class Black women and families.”Black, 31 y/o, New Jersey.

“Education on safe sleep and explaining that even if it generational to sleep with your infant, it is a risk every time that the baby goes to sleep.”White, 33 y/o, Indiana.

2.1.3. Supporting Breastfeeding

“Breastfeed and find breastfeeding support to try to reduce risk for premature death.”White, 47 y/o, Indiana.

“Try to breastfeed for as long as possible and read up on the information that’s currently available.”Black, 29 y/o, Mississippi.

2.1.4. Awareness

“Lack of awareness and emphasis on protecting and educating mothers.”White, 28 y/o, Indiana.

“Education of mothers about pregnancy and expectations.”Black, 43 y/o, Indiana.

2.1.5. Affordability Challenges and Healthcare Provider Factors

“Lack of urgency in assisting mothers due to implicit bias.”Black, 24 y/o, New York.

“Negligence of [sick ‘by’] medical staff.”Black, 3 y/o, Texas.

“Access to quality healthcare, awareness and education of resources, change socioeconomic status, change affordability.”Black, 35 y/o, California.

2.1.6. Creating Sustainable Programs and Policies to Address Infant Mortality

“Programs or services to address the environments these infants live in as well as increased education for not only parents but the support system/family members of the infant.”Black, 28 y/o, Indiana.

“Policies, training, advocacy.”White, 47 y/o, Indiana.

“Advocate, advocate. Speak up. Listen to your intuition and ask about resources. Demand the best for your baby starting at conception until adulthood.”Black, 45 y/o, Tennessee.

3. Discussion

3.1. Limitations

3.2. Policy Solutions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Participants

4.2. Research Questions

- Precontemplation: At the pre-contemplation stage (the initial stage), people do not anticipate taking serious action regarding changing their behavior.

- Contemplation: It is at the contemplation stage that people consider a change.

- Preparation: People see their behavior as problematic at the preparation stage and commit to a change.

- Action: At this stage, action is made, and people plan to keep their actions.

- Maintenance: Finally, people try to avoid returning to their previous behavior/situation at the maintenance stage.

4.3. Study Design

4.4. Instrument

4.5. Eligibility and Participants

4.6. Recruitment

4.7. Data Coding and Analysis

4.7.1. Closed-Ended Items (Quantitative Data Analysis)

4.7.2. Open-Ended Items (Qualitative Data Analysis)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ely, D.M.; Driscoll, A.K. Infant mortality in the United States, 2017: Data from the period linked birth/infant death file. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 2019, 68, 80304. [Google Scholar]

- Ely, D.M.; Driscoll, A.K. Infant mortality in the United States, 2022: Data from the period linked birth/infant death file. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 2024, 73, 157006. [Google Scholar]

- Papanicolas, I.; Woskie, L.R.; Orlander, D.; Orav, E.J.; Jha, A.K. The relationship between health spending and social spending in high-income countries: How does the US compare? Health Affairs 2019, 38, 1567–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.L.; Burton, R. US Health Care Spending: Comparison with Other OECD Countries; Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- CIA-World-Factbook. Infant Mortality Rate. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/infant-mortality-rate/country-comparison/ (accessed on 19 October 2024).

- United-Health-Foundation. America’s Health Rankings. Available online: https://www.americashealthrankings.org/learn/reports/2023-annual-report (accessed on 19 October 2024).

- Ely, D.M.; Driscoll, A.K. Infant Mortality by Selected Maternal Characteristics and Race and Hispanic Origin in the United States, 2019–2021. Natl. Vital. Stat. Rep. 2024, 73, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, G.K.; Stella, M.Y. Infant mortality in the United States, 1915-2017: Large social inequalities have persisted for over a century. Int. J. Matern. Child Health AIDS 2019, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, S.H.; Hummer, R.A.; Sierra, G.; Hargrove, T.; Powers, D.A.; Rogers, R.G. Race/ethnicity, maternal educational attainment, and infant mortality in the United States. Biodemography Soc. Biol. 2021, 66, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, E.J.; Becker, A.; Baluran, D.A. Gendered racism on the body: An intersectional approach to maternal mortality in the United States. Pop. Res. Policy Rev. 2022, 41, 1261–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliam, S.M.; Hylick, K.; Taylor, E.N.; La Barrie, D.L.; Hatchett, E.E.; Finch, M.Y.; Kavalakuntla, Y. Intersectionality in Black maternal health experiences: Implications for intersectional maternal mental health research, policy, and practice. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2024, 69, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ely, D.M.; Driscoll, A.K. Infant mortality in the United States, 2019: Data from the period linked birth/infant death file. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 2021, 70, 111053. [Google Scholar]

- Bower, K.M.; Geller, R.J.; Perrin, N.A.; Alhusen, J. Experiences of racism and preterm birth: Findings from a pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system, 2004 through 2012. Women’s Health Issues 2018, 28, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvonen, K.L.; McKenzie-Sampson, S.; Baer, R.J.; Jelliffe-Pawlowski, L.; Rogers, E.E.; Pantell, M.S.; Chambers, B.D. Structural racism is associated with adverse postnatal outcomes among Black preterm infants. Pediatr. Res. 2023, 94, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens-Young, J.; Bell, C.N. Structural racial inequities in socioeconomic status, urban-rural classification, and infant mortality in US counties. Ethn. Dis. 2020, 30, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, A.T.; Crookes, D.M.; Suglia, S.F.; Demmer, R.T. The weathering hypothesis as an explanation for racial disparities in health: A systematic review. Ann. Epidemiol. 2019, 33, 1–18.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sayed, A.M.; Paczkowski, M.; Rutherford, C.G.; Keyes, K.M.; Galea, S. Social environments, genetics, and Black–White disparities in infant mortality. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol 2015, 29, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P.N. Maternal age and infant mortality for white, black, and Mexican mothers in the United States. Sociol. Sci. 2016, 3, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagher, R.K.; Linares, D.E. A critical review on the complex interplay between social determinants of health and maternal and infant mortality. Children 2022, 9, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoku, A.; Evans, M.; Nimo-Sefah, L.; Bailey, J. Listen to the whispers before they become screams: Addressing Black maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States. Healthcare 2023, 11, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, T.J.; Darrow, L.A.; Parker, J.D. Air pollution and postneonatal infant mortality in the United States, 1999–2002. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008, 116, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Womack, L.S.; Rossen, L.M.; Hirai, A.H. Urban–rural infant mortality disparities by race and ethnicity and cause of death. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 58, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenthal, D.B.; Kuo, H.-H.D.; Kirby, R.S. Infant mortality in rural and nonrural counties in the United States. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20200464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamoud, Y.A.; Kirby, R.S.; Ehrenthal, D.B. Poverty, urban-rural classification and term infant mortality: A population-based multilevel analysis. BMC Preg. Childbirth 2019, 19, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.; Redmond, M.; Stites, S.; Sims, J.; Ramaswamy, M.; Kelly, P.J. Creating an Agenda for Black Birth Equity: Black Voices Matter. Health Equity 2023, 7, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Foundation for Black Women’s Wellness. Saving Our Babies: Low Birthweight Engagement Final Report. Report. 2018. Available online: https://www.ffbww.org/saving-our-babies (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Peyton-Caire, L.; Stevenson, A. Listening to Black Women: The Critical Step to Eliminating Wisconsin’s Black Birth Disparities. WMJ 2021, 39, S39–S41. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska, J.O.; DiClemente, C.C. Transtheoretical therapy: Toward a more integrative model of change. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 1982, 19, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yearby, R. Racial disparities in health status and access to healthcare: The continuation of inequality in the United States due to structural racism. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 2018, 77, 1113–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, V.C. African Americans: Disparities in health care access and utilization. Health Soc. Work 2005, 30, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajao, T.I.; Oden, R.P.; Joyner, B.L.; Moon, R.Y. Decisions of black parents about infant bedding and sleep surfaces: A qualitative study. Pediatrics 2011, 128, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willinger, M.; Hoffman, H.J.; Wu, K.-T.; Hou, J.-R.; Kessler, R.C.; Ward, S.L.; Keens, T.G.; Corwin, M.J. Factors associated with the transition to nonprone sleep positions of infants in the United States: The National Infant Sleep Position Study. JAMA 1998, 280, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Mohammed, S.A. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. J. Behav. Med. 2009, 32, 20–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahm, P.; Valdes, V. Benefits of breastfeeding and risks associated with not breastfeeding. Rev. Chil. Pediatr. 2017, 88, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kornides, M.; Kitsantas, P. Evaluation of breastfeeding promotion, support, and knowledge of benefits on breastfeeding outcomes. J. Child Health Care 2013, 17, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obeng, C.; Jackson, F.; Nsiah-Asamoah, C.; Amissah-Essel, S.; Obeng-Gyasi, B.; Perry, C.A.; Gonzalez Casanova, I. Human milk for vulnerable infants: Breastfeeding and milk sharing practice among Ghanaian women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gribble, K.D.; McGrath, M.; MacLaine, A.; Lhotska, L. Supporting breastfeeding in emergencies: Protecting women’s reproductive rights and maternal and infant health. Disasters 2011, 35, 720–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupton, D.A. ‘The best thing for the baby’: Mothers’ concepts and experiences related to promoting their infants’ health and development. Health Risk Soc. 2011, 13, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauritzen, S.O. Notions of child health: Mothers’ accounts of health in their young babies. Soc. Health Illn. 1997, 19, 436–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, K. Can you hear me?: How implicit bias creates a disparate impact in maternal healthcare for Black women. Campbell L. Rev. 2021, 43, 243. [Google Scholar]

- Saluja, B.; Bryant, Z. How implicit bias contributes to racial disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States. J. Women’s Health 2021, 30, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, R. Implicit Bias in Healthcare: Maternal and Infant Morbidity and Mortality in Minority Patients. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburg, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, A.H.; Altman, M.R.; Canty, L.; Edmonds, J.K. Communication between pregnant people of color and prenatal care providers in the United States: An integrative review. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2024, 69, 202–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, W.J.; Chapman, M.V.; Lee, K.M.; Merino, Y.M.; Thomas, T.W.; Payne, B.K.; Eng, E.; Day, S.H.; Coyne-Beasley, T. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: A systematic review. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, e60–e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.R.; Carney, D.R.; Pallin, D.J.; Ngo, L.H.; Raymond, K.L.; Iezzoni, L.I.; Banaji, M.R. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for black and white patients. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2007, 22, 1231–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zestcott, C.A.; Blair, I.V.; Stone, J. Examining the presence, consequences, and reduction of implicit bias in health care: A narrative review. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2016, 19, 528–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, K.S.; Banks, A.R.; Morton, T.; Sander, C.; Stapleton, M.; Chisolm, D.J. “I just want us to be heard”: A qualitative study of perinatal experiences among women of color. Women’s Health 2022, 18, 17455057221123439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClellan, C.; Madler, B. Lived experiences of Mongolian immigrant women seeking perinatal care in the United States. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2022, 33, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coley, S.L.; Zapata, J.Y.; Schwei, R.J.; Mihalovic, G.E.; Matabele, M.N.; Jacobs, E.A.; Anderson, C.K. More than a “number”: Perspectives of prenatal care quality from mothers of color and providers. Women’s Health Issues 2018, 28, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmonds, B.T.; Mogul, M.; Shea, J.A. Understanding low-income African American women’s expectations, preferences, and priorities in prenatal care. Fam. Comm. Health 2015, 38, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.Y.; Kim, W.; Dickerson, S.S. Korean immigrant women’s lived experience of childbirth in the United States. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2014, 43, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, J.D. Understanding prenatal health care for American Indian women in a Northern Plains tribe. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2012, 23, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramling, L.; Hickman, K.; Bennett, S. What makes a good family-centered partnership between women and their practitioners? A qualitative study. Birth 2004, 31, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, M.R.; Oseguera, T.; McLemore, M.R.; Kantrowitz-Gordon, I.; Franck, L.S.; Lyndon, A. Information and power: Women of color’s experiences interacting with health care providers in pregnancy and birth. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 238, 112491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, L.A.; Raffo, J.E.; Dertz, K.; Agee, B.; Evans, D.; Penninga, K.; Pierce, T.; Cunningham, B.; VanderMeulen, P. Understanding perspectives of African American Medicaid-insured women on the process of perinatal care: An opportunity for systems improvement. Matern. Child Health J. 2017, 21, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazul, M.C.; Salm Ward, T.C.; Ngui, E.M. Anatomy of good prenatal care: Perspectives of low income African-American women on barriers and facilitators to prenatal care. J. Rac. Ethn. Health Disparities 2017, 4, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheatley, R.R.; Kelley, M.A.; Peacock, N.; Delgado, J. Women’s narratives on quality in prenatal care: A multicultural perspective. Qual. Health Res. 2008, 18, 1586–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheppard, V.B.; Zambrana, R.E.; O’Malley, A.S. Providing health care to low-income women: A matter of trust. Fam. Pract. 2004, 21, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.L.; Lurie, N. The role of culturally competent communication in reducing ethnic and racial healthcare disparities. Am. J. Manag. Care 2004, 10, SP1–SP4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.; Brennan, M.J. Great Expectations: Baby Sleep Guide; Union Square & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, N.L.; McKenzie, L.B.; Anderson, S.E.; Katz, M.L. Exploring lactation consultant views on infant safe sleep. Matern. Child Health J. 2018, 22, 1111–1117. [Google Scholar]

- Gorenflo, G.; Rich, N.; Adams-McBride, M.; Hilliard, C. The power of community in addressing infant mortality inequities. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2022, 28, S70–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broom, M.; Youseman, M.E.; Kent, A.L. Impact of introducing a lactation consultant into a neonatal unit. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2022, 58, 636–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagon, E.P.; Mitchell, C.; Bryant, A.C.; Bibbo, C. The Inequity Inbox: A model for addressing bias in the clinical environment. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2022, 4, 100666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, J.B.; Cavenagh, Y.; Bender, K.K. Planning, Implementation, and Evaluation of a Postpartum Nurse Home Visit Service to Improve Health Equity. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2024, 53, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renbarger, K.M.; Abebe, S.; Place, J.M.; Goldsby, E.; Hall, G.; Kroot, A. Perspectives of infant mortality from African American community members. Women’s Health Rep. 2023, 4, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown Speights, J.S.; Mitchell, M.M.; Nowakowski, A.C.; De Leon, J.; Simpson, I. Exploring the cultural and social context of Black infant mortality. Pract. Anthr. 2015, 37, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Danzine, V.V. African American Mothers’ Perceptions of Infant Mortality Factors. Ph.D. Thesis, Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Overall n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

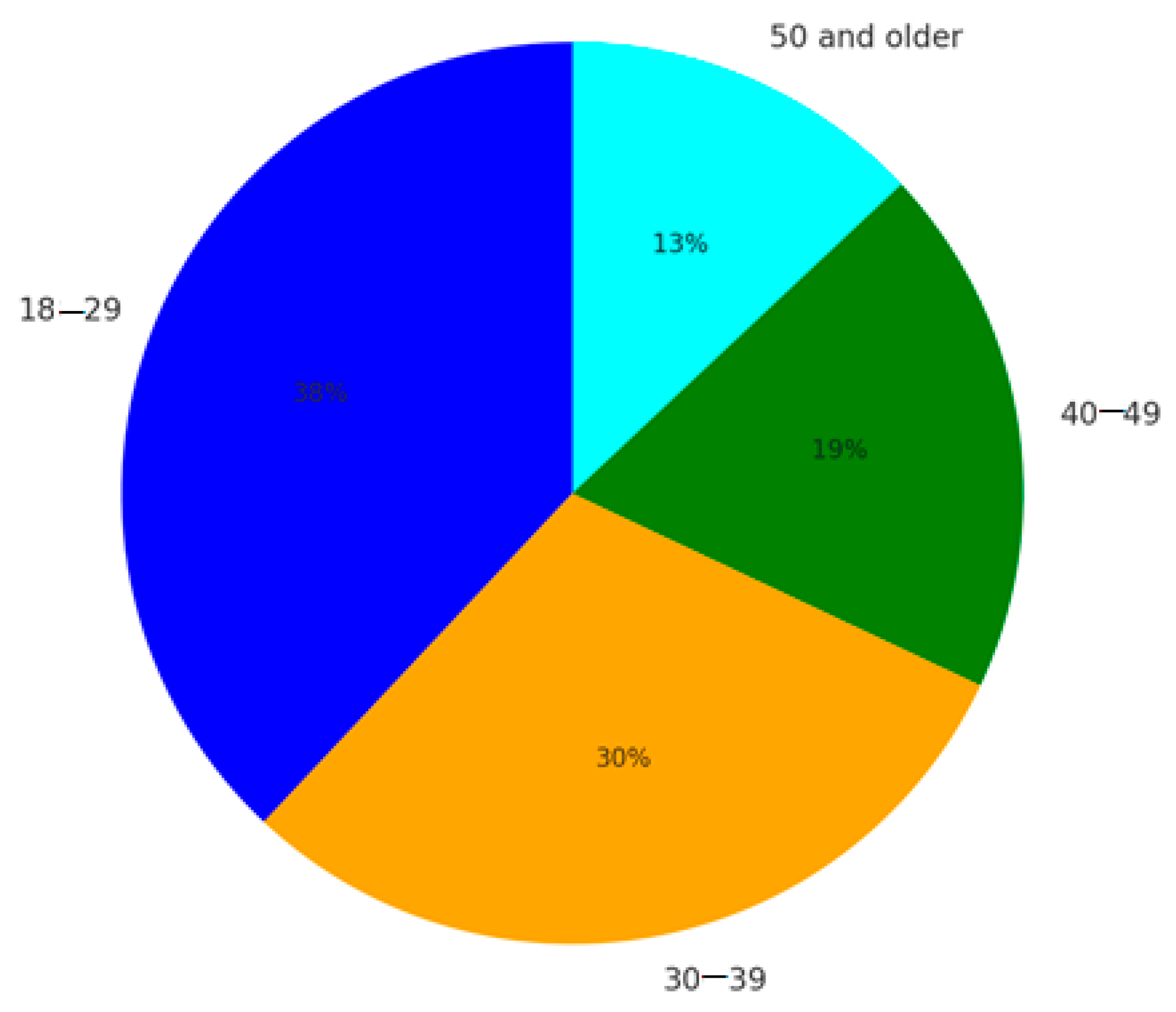

| Age | ||

| 18–29 | 35 (38.4) | |

| 30–39 | 27(29.7) | |

| 40–49 | 17 (18.7) | |

| 50 and older | 12 (13.2) | |

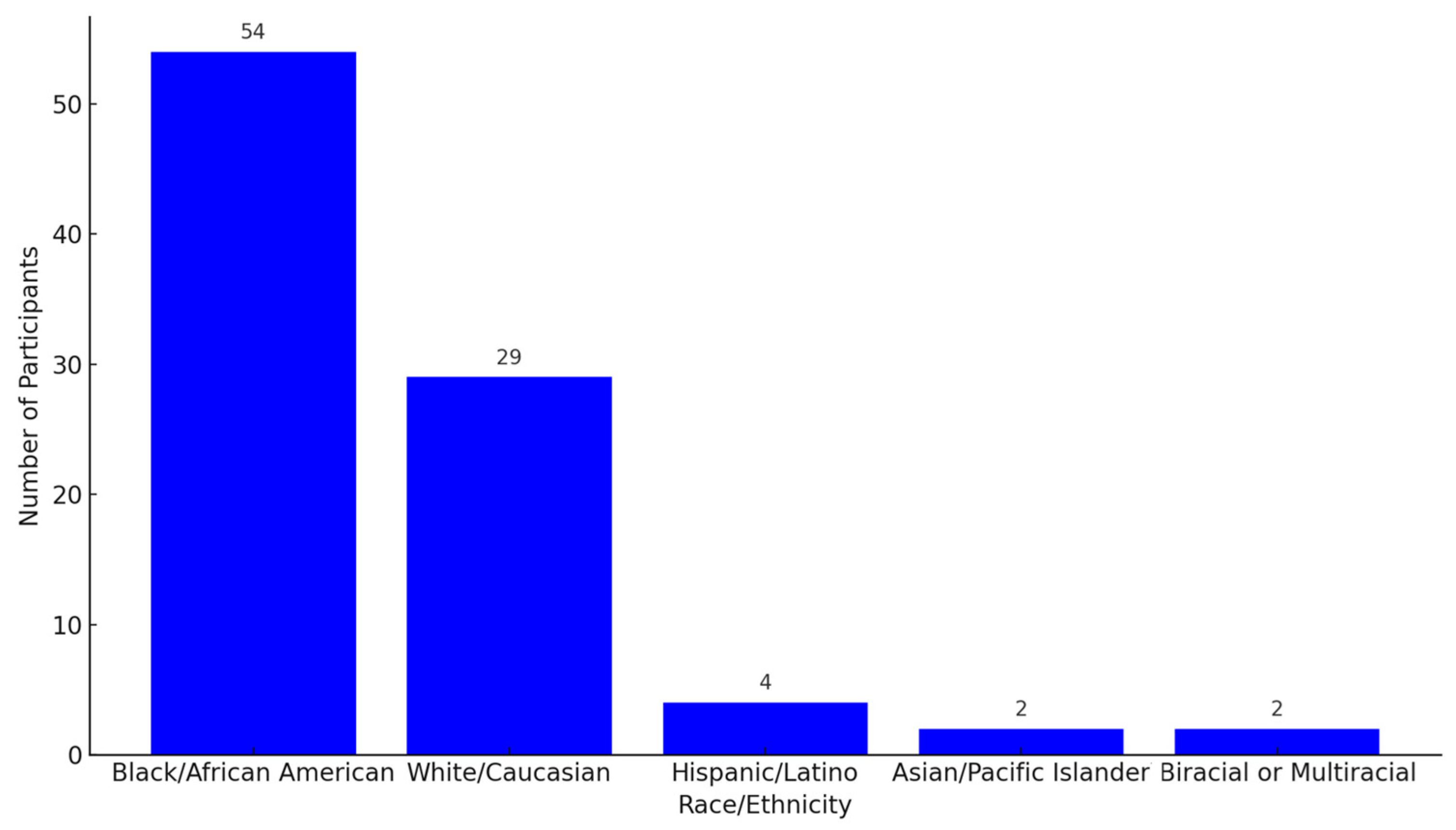

| Race | ||

| Black/African American | 54 (59.3) | |

| White/Caucasian | 29 (31.9) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 4 (4.4) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2 (2.2) | |

| Biracial or multiracial | 2 (2.2) | |

| Parental Status (mother) | ||

| Yes | 41 (45.1) | |

| No | 50 (54.9) | |

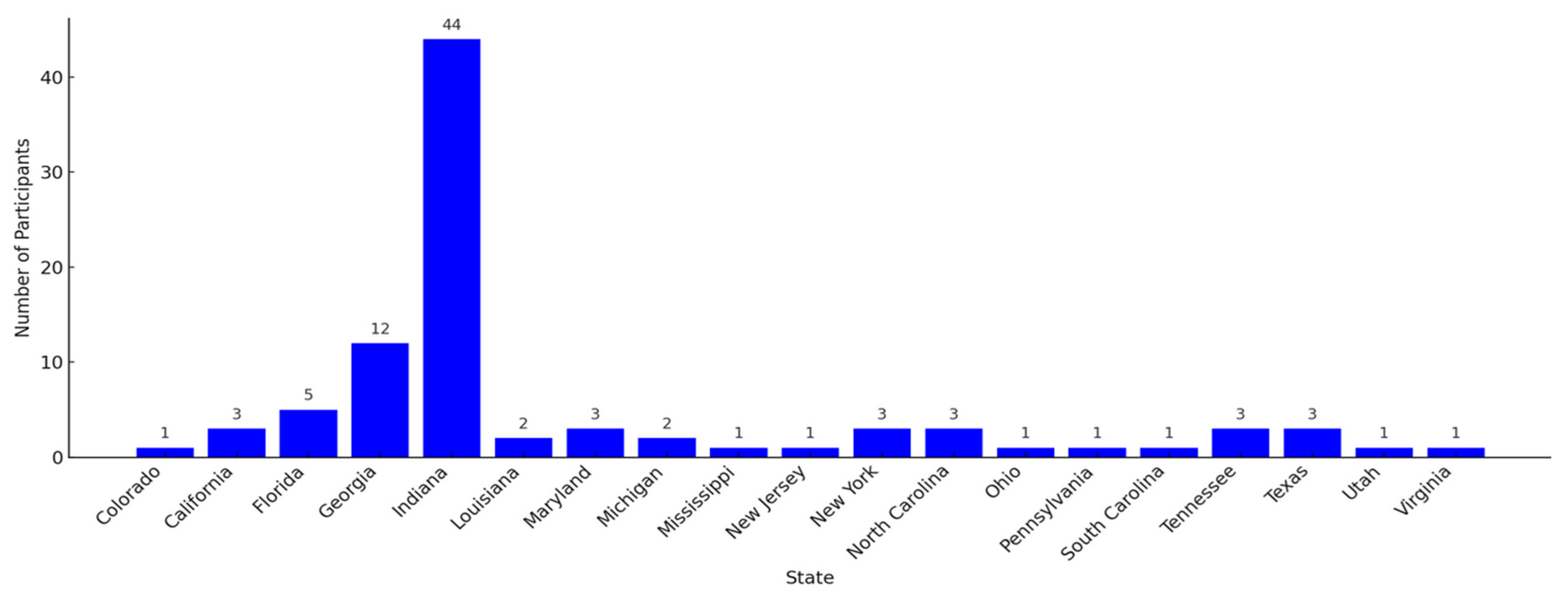

| US State | ||

| Colorado | 1 (1.1) | |

| California | 3 (3.3) | |

| Florida | 5 (5.5) | |

| Georgia | 12 (13.2) | |

| Indiana | 44 (48.4) | |

| Louisiana | 2 (2.2) | |

| Maryland | 3 (3.3) | |

| Michigan | 2 (2.2) | |

| Mississippi | 1 (1.1) | |

| New Jersey | 1 (1.1) | |

| New York | 3 (3.3) | |

| North Carolina | 3 (3.3) | |

| Ohio | 1 (1.1) | |

| Pennsylvania | 1 (1.1) | |

| South Carolina | 1 (1.1) | |

| Tennessee | 3 (3.3) | |

| Texas | 3 (3.3) | |

| Utah | 1 (1.1) | |

| Virginia | 1 (1.1) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Obeng, C.S.; Nolting, T.M.; Jackson, F.; Obeng-Gyasi, B.; Brandenburg, D.; Byrd, K.; Obeng-Gyasi, E. Women’s Perspectives on Black Infant Mortality in the United States. Women 2024, 4, 514-528. https://doi.org/10.3390/women4040038

Obeng CS, Nolting TM, Jackson F, Obeng-Gyasi B, Brandenburg D, Byrd K, Obeng-Gyasi E. Women’s Perspectives on Black Infant Mortality in the United States. Women. 2024; 4(4):514-528. https://doi.org/10.3390/women4040038

Chicago/Turabian StyleObeng, Cecilia S., Tyler M. Nolting, Frederica Jackson, Barnabas Obeng-Gyasi, Dakota Brandenburg, Kourtney Byrd, and Emmanuel Obeng-Gyasi. 2024. "Women’s Perspectives on Black Infant Mortality in the United States" Women 4, no. 4: 514-528. https://doi.org/10.3390/women4040038

APA StyleObeng, C. S., Nolting, T. M., Jackson, F., Obeng-Gyasi, B., Brandenburg, D., Byrd, K., & Obeng-Gyasi, E. (2024). Women’s Perspectives on Black Infant Mortality in the United States. Women, 4(4), 514-528. https://doi.org/10.3390/women4040038