Abstract

There are significant hurdles to placing pregnant and parenting women (PPW) with a substance use disorder into treatment programs. This study uses qualitative analysis of case notes collected by a linkage to care expert (patient navigator) from over 50 Mississippi PPW client cases. The analysis identified facilitators and barriers in the referral to treatment process. We group the observed patterns into three general categories: (1) individual factors such as motivation to change and management of emotions; (2) interpersonal relationships such as romantic partner support or obstruction; and (3) institutional contexts that include child welfare, judicial, and mental health systems. These factors intersect with one another in complex ways. This study adds to prior research on gender-based health disparities that are often magnified for pregnant and parenting women.

1. Introduction

Substance use has posed a significant public health concern across the United States for decades. In the U.S., approximately 40% of citizens with a lifetime substance use disorder (SUD) or with reoccurring substance use are women [1]. The etiology of an SUD is multifactorial, with a potent mix of genetic, environmental, psychological, biological, and socioeconomic factors contributing to individual susceptibility [2]. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) surveyed individuals ages 12 and older in 2021, with results showing that millions of adult women struggle with drug use disorder (9.7 million) or alcohol use disorder (12.3 million), and millions more have a co-occurring SUD and mental illness (10.5 million) [3]. Female parents are less likely to be diagnosed with an SUD or receive medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) than male parents. Among parents with opioid use disorder (OUD), the average predicted prevalence of receiving MOUD was 27.4% among male and 19.7% among female parents of children younger than five years of age [4]. Between 1999 and 2014, national opioid use disorder prevalence increased 333% among pregnant women, up from 1.5 cases per 1000 delivery hospitalizations to 6.5 cases across 28 U.S. states [5]. Research points to a common decrease in substance use by many women during pregnancy. Some women can quit using substances without any treatment or assistance, which is the primary distinguishing factor between general substance use and substance use disorders (SUD) [1]. However, substance use among women during pregnancy is often addressed to encourage temporary abstinence rather than full cessation, which can increase the probability of post-pregnancy resumption in substance use across racial groups [6].

Several factors are associated with maternal and infant consequences of substance use. Regular use of certain substances can cause neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), in which the baby goes through withdrawal upon birth, at which point the child is often placed in Child Protective Services (CPS) custody. Research in this area has primarily centered around the effects of opioids (prescription pain relievers or heroin). However, recent data have shown that the use of alcohol, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, and caffeine during pregnancy may also cause NAS [7]. Most common co-occurring factors are psychiatric comorbidity, polysubstance use, limited prenatal care, environmental stressors, and disrupted parental care. Such factors have proven to influence pregnancy and infant outcomes adversely and are rarely considered when developing interventions for prenatal substance use treatments [8]. Many of the health problems associated with substance use in the prenatal period could be avoided given effective and well-timed medical care or intervention.

Motivators among pregnant and parenting women to seek substance use treatment include readiness to stop using, concern for their infant’s health and well-being, potential loss of custody over their infant or other children, the desire to leave a violent environment, or homelessness [8,9,10,11]. Despite having monumental motivating factors, many mothers with substance use disorder experience notable barriers to treatment access. Barriers include mental illness, fearing loss of custody if child welfare services or court orders are not already involved, not wanting to be separated from children or a romantic partner because of inpatient treatment, stigma or lack of privacy, and lack of childcare and transportation [9,11]. Language, beliefs about gender roles, and attitudes around parental fitness are determinative social factors that perpetuate stigma while facilitating disciplinary rather than therapeutic approaches to treatment access. Stigmatizing attitudes include the belief that a person who uses substances is unfit to parent. Therefore, pregnant women who use substances are at an elevated risk of being screened for substance use, referred to child welfare services, and being stripped of their parental rights. Such outcomes are even more likely to take place among people of color [12,13,14,15]. There have been developmental studies related to the implementation of screening programs for depression and other mental health issues co-occurring with substance use and intimate partner violence or other forms of abuse [16,17]. However, the implementation of outpatient treatment for co-occurring health issues highlights distinct client vulnerabilities towards treatment incompletion or avoidance (i.e., care provider role perception and stigma, education on treatment, transportation reliability, healthcare insurance, childcare services).

Integrated treatment programs have been developed to address the diverse needs of women. Treatment programs such as these offer a holistic and comprehensive mix of services that are trauma- and violence-informed with a focus on maternal and child health promotion and the development of healthy relationships [18]. Coordination across agencies and sectors at the levels of service delivery and policy implementation formed integral aspects of what constitutes effective integrated care for the maternal SUD population and contributes to how these programs can maintain engagement among the women who access them. A research study of women’s perspectives on integrated care program participation revealed the central role played by counselor (i.e., patient navigator, social worker) support for the emotional regulation and executive functioning features of therapeutic treatment [19]. The use of a patient navigator, while not widely studied in maternal SUD treatment facilitation, is a notable asset in linkage to care for treatment initiation and completion among various populations. Multi-sectoral service coordination and therapeutic support for emotion regulation and executive functioning are particularly important for pregnant and parenting women who are accessing substance use services, given social and structural barriers to health (e.g., poverty, substance-related stigma, gender discrimination). Findings suggest that these integrated treatment programs have achieved a level of success in developing cross-sectoral partnerships with child welfare services, parenting and child support, and social services featured prominently in the networks. By contrast, there was a lack of close connections with physician-based services. Another community-based, multi-service program study focused on the social determinants of health and their provision of primary, prenatal, perinatal, and mental health care services as essential. Similarly, on-site substance use and trauma- or violence-related services were crucial topics to be addressed with clients. The results reveal that programs’ support of women’s child welfare issues promotes collaboration, contributes to understanding of expectations, and aids in the prevention of child or infant parental removals [20]. Overall, women in integrated or multi-sector programs perceive these programs more positively than standard care interventions. Substance use and mental health are the most common areas of treatment. Childcare and transportation are identified as the most helpful aspects but are far less common. Holistic services, such as the use of a patient navigator in linkage to care efforts, that address the well-being of both mothers and their children are needed [21].

Treatment initiation shortfalls for referred clients are prevalent across the United States but are especially so in Mississippi. Drug treatment program referrals are often unresolved, resulting in an indeterminate outcome of referral regarding program utilization, quality, and impact for each client. The lack of follow-up with clients (also commonly referred to as patients) typically yields low substance use treatment initiation and completion rates. Cross-sector referrals, such as district courts and primary care to behavioral health centers, present often unyielding challenges to the public health field concerning substance use disorder treatment. The current study expands on previous research on multi-sector programs for pregnant and parenting women with SUDs through the analysis of an SUD treatment referral pilot program using a linkage to care expert or patient navigator. The use of a patient navigator in treatment referrals, placement, and follow-up addresses the gap made by the aforementioned treatment barriers. Using qualitative analyses of client case notes provided by the patient navigator, this study aims to render an in-depth examination of client motivations related to treatment initiation. Factors include individual, interpersonal, and institutional contexts as shared with and noted by the patient navigator. Furthermore, the study’s findings propose that the patient navigator acts as a significant facilitator to treatment with women experiencing an SUD. Case notes written by the patient navigator for Mississippi’s OD2A Pregnant and Parenting Women pilot program could yield promising results for future programs through tracking successful client substance use treatment initiation and completion pathways.

2. Results

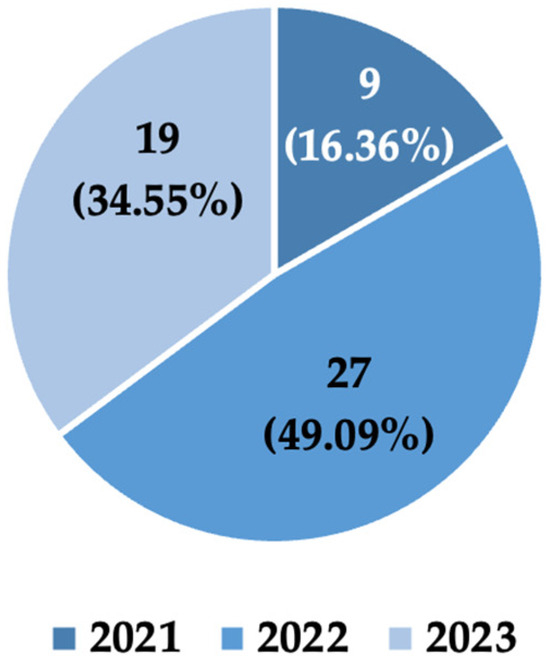

Analyses from the case notes prepared by the patient navigator representing the Pregnant and Parenting Women (PPW) program, designated the Mississippi OD2A Referral Enhancement Pilot Study (REPS), are presented in this section. The PPW program was created as part of Mississippi’s Overdose Data to Action (OD2A) grant project, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2019. The program, while drafted and prepared for launch in 2020, was significantly delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic conditions offered a unique opportunity for the patient navigator and the OD2A team to implement program adaptations that were, prior to 2020, underutilized (i.e., telecommunication with clients and partners). In 2021, the patient navigator officially began to work with referrals of pregnant and parenting women with substance use disorders. Public outreach during that time was often limited by pandemic health and safety restrictions. However, the count increases from 2021 to 2022 and 2023 (see annual referral counts in Figure 1) demonstrate the results of consistent practices put forth by the patient navigator. Through innovative pathways (e.g., court attendance to speak with district judges, a flexible “on-call” schedule for in-person and virtual meetings at any time), the patient navigator cultivated longstanding relationships with a variety of agencies and institutions directly connected to the clients served by the PPW program (see Table 1).

Figure 1.

PPW (female) client referrals by year with corresponding counts and percentages. Indicates the number of clients referred to the patient navigator from various sources (e.g., physician offices, judicial courts, and other clients who completed treatment programs). Counts include one return referral case per year (three return referral cases total).

Table 1.

Agencies partnered with the OD2A Pregnant and Parenting Women program, formed and maintained by the patient navigator.

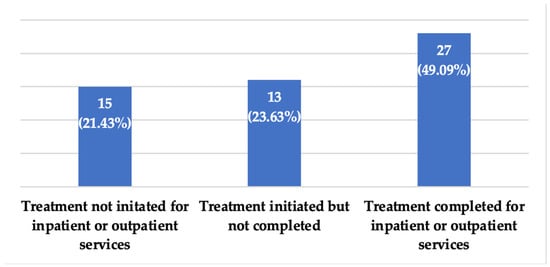

The PPW program was originally implemented to aid women with a substance use disorder who were either pregnant, parenting children under the age of 5, or both. However, the clientele was expanded in the third and final year to include men with a substance use disorder while parenting young children. In this study, the case notes provided by the PPW patient navigator and analyzed by the project evaluators related only to female clients served. The patient navigator was an essential element and driving force of the program’s success. Case notes reflect the navigator’s standpoint as a patient advocate and are analyzed as situated reflections. Case notes included client referral and treatment status counts (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). Client referrals increased approximately 111% from baseline (9 referrals, 2021) to the final program year (19 referrals, 2023). Likewise, client treatment statuses varied between treatment never initiated (15 cases), treatment initiated but incomplete (13 cases), and treatment fully completed (27 cases). The study authors acknowledge that others involved in these often challenging circumstances may have a different set of primary considerations or obligations depending on their role and position. This point is not conveyed to express doubt about the navigator’s reflections but recognizes the complexity of the knowledge-building process.

Figure 2.

PPW (female) client treatment statuses in the program between 2021 and 2023. Counts include a total of three return referral cases.

The presentation of results is structured around three primary categories from analyses of case note observations (individual factors, interpersonal relationships, and institutional contexts). Results are described according to various client experiences prior to and during their time in contact with the patient navigator as understood by the patient navigator in client case notes. Some clients chose to maintain contact with the patient navigator even if treatment was not pursued, after treatment was completed, or if a relapse occurred. The continued client contact speaks to the dedication and rapport-building put forth by the patient navigator. The complex and intersecting aspects of clients’ social experiences (intrinsic motivators, relationships, and institutional interactions) are displayed through key elements conveyed to the patient navigator.

2.1. Individual Factors

2.1.1. Motivation to Change

There are intersecting social inhibitors for SUD treatment initiation and completion. Throughout the implementation timeline of the PPW program, the patient navigator worked one-on-one with clients, learning their personal histories of abuse and neglect and motivations for treatment pursuit. Among key findings, the patient navigator noted four primary reasons clients requested meetings for treatment referrals: (1) treat SUD as a mandate of the court, (2) treat SUD for the sake of the child’s health, (3) treat SUD to maintain or regain custody of the child, and (4) treat SUD to move out of an unstable, unsafe environment and way of life. One caveat to having positive extrinsic motivators is the presence or lack of intrinsic motivation. Put differently, if the client does not have a strong internal desire to overcome substance use dependency or if treatment fears have not been thoroughly addressed, the client will typically employ avoidant actions to circumvent treatment, as seen in Natalie’s case. The patient navigator offered a unique opportunity for women with SUD to form a close bond with a professional in the linkage to care network, as with Esther’s case. In contrast, before the PPW program, clients were numerous and indistinguishable, and many treatment-related efforts went undocumented.

Initially, she [Natalie] was highly motivated to go to treatment. After she was admitted to a treatment center, she found out that she was pregnant. When staff told her that she would have to stay for the entire pregnancy, the client wanted to leave. She left the treatment center without completing treatment. (The patient navigator’s notes on Natalie’s case)

Establishing a good rapport and building trust from the first encounter with the client [Esther]. Even though she declined to enroll in the grant program initially, she changed her mind later and wanted to go to Jacob’s Well for treatment. Navigator contacted Jacob’s Well and they were able to get the client a sponsored bed. The client successfully completed treatment at Jacob’s Well and will stay on as staff for the pregnancy program at Jacob’s Well. (The patient navigator’s notes on Esther’s case)

In some cases, intrinsic motivation emanates from extrinsic circumstances, such as gaining child custody or seeking safety. The patient navigator establishing an inter-organizational network of primary care offices, homeless shelters, county courts, and others often paved the way for women to gain access to the benefits of the PPW program. In some circumstances, a compassionate and knowledgeable linkage to a care expert was needed to navigate treatment options, as well as relationships with family members, judicial officials, and treatment administrators alongside the client. This co-navigation often took place as key updates were shared with the patient navigator related to court requests, caseworker stipulations, and family disputes or supports. The information gathered by the patient navigator enabled the client to build trust and empowerment through the process and partake in treatment services.

The client [Sabrina] had confided in her child’s provider that she needed help with substance use disorder. The provider contacted the navigator immediately. The navigator immediately contacted the client and plans were made to meet the next day to discuss treatment options. The client was highly motivated to go to treatment. Utilizing the most effective strategies of quick response to the provider’s referral and quickly building rapport and trust with the client resulted in this client successfully completing rehab. (The patient navigator’s notes on Sabrina’s case)

The client’s counselor reported that she is doing very well in treatment. She is working on setting healthy boundaries with family and working through trauma. She has started going on home visits and they are going well for her. The client was highly motivated to go to treatment. Utilizing the most effective strategies of quick response to the provider’s referral and quickly building rapport and trust with the client resulted in this client successfully completing rehab. (The patient navigator’s notes on Sabrina’s case)

This client was a self-referral. She walked into the clinic where the navigator’s office is and told the front desk she was looking for a Suboxone Clinic. They informed the navigator of the client’s request and then sent the client to the navigator’s office. When the navigator started inquiring what she was searching for and why, it became apparent that she would be an OD2A client. The navigator informed the client that she had come to the right place and that she would never be judged or treated poorly. The client immediately felt relaxed and at ease at this point and stated, “God knew where to send me”. She informed the navigator that her children had been taken into custody and she needed to go to treatment. A trusting relationship was built quickly with this client. She was receptive to all suggestions and advice of the navigator. (The patient navigator’s notes on Sally’s case)

The patient navigator’s efforts to provide open conversations without judgment while also presenting positive action steps for the client to take was a key element in the success of many clients. In a traditional linkage to care effort, the dialogue for SUD client care between organizations (primary care, court systems, treatment facilities, etc.) is stilted and, in some locations and client cases, non-existent. Introducing the new role of a navigator designed to put the “link” into linkage to care for SUD clients ultimately expanded the conversation around client treatment and encouraged a higher treatment completion success rate.

The navigator sat with her [Clara] and listened to her, talked with her, comforted her, and promised to be her support and help her navigate through the journey of becoming sober again and changing her life. The client felt relieved that someone was “on her side”. As the navigator was leaving, the client stated, “If I have you, then I can do this”. (The patient navigator’s notes on Clara’s case)

2.1.2. Emotional Management

Mental illness is a significant factor in SUDs and is often difficult to address in the population of pregnant women. The patient navigator noted several cases wherein mental health issues were the primary barrier to the client receiving or completing inpatient treatment. Paranoia and cognitive deficiencies or delays inhibited several clients from understanding the PPW program practices and benefits of treatment. However, in one case, outpatient medication-assisted treatment (MAT) was successfully paired with outpatient psychotherapy sessions. Once more, the efforts of the patient navigator to establish open communication between health and treatment entities were crucial to the client’s treatment success.

Client [Calista] has not rescheduled the appointment for outpatient treatment or counseling. She feels that she doesn’t have enough time to do this as she has a lot going on with an intensive, home and community-based family preservation, reunification, and support services program visiting her at her home 3–4 times a week, seeing a psychiatrist, seeing a therapist, and GI appointments. She feels she is getting all the help she needs now. (The patient navigator’s notes on Calista’s case)

Behavioral issues have been known to co-occur with an SUD. As with Terra’s case, the lack of applied behavioral management outside of SUD inpatient treatment inhibited the client from upwardly mobile job, housing, and relationship opportunities.

The client’s mother contacted the navigator and to vent about her daughter [Terra] “getting in trouble” at the inpatient facility. The navigator contacted facility intake manager to discuss the issue. The intake manager informed the navigator that they might have to call the police because the client had attempted to “hit” another resident at the Thrift Store where they work. The client contacted the navigator and stated that one of the other clients had been “picking” on her. The client agreed to stay at rehab and work on herself. The client was caught stealing from the Thrift Store. Due to this and her other behavioral issues, she was discharged from the inpatient treatment facility. (The patient navigator’s notes on Terra’s case)

2.2. Interpersonal Relationships

2.2.1. Romantic Partner Support or Obstruction

Social contexts influencing substance use and other health-averse behaviors are often interconnected. For example, romantic partners can either encourage the client to stop or continue substance use through control over physical environment, social isolation, or emotional vulnerability or manipulation. Building rapport between the patient navigator and client encourages the client to develop self-confidence in their ability to recover and not lean unhealthily on romantic relationships. In Bella’s case, the client reached out to the navigator months after she was lost to follow-up, defined in this study as having no further contact with the patient navigator, due to her then-current situation of homelessness and substance use. The rapport built by the patient navigator laid the foundation for the client to separate from unhealthy relationship constraints and develop the independence to receive inpatient treatment. A significant aspect of emotional dependence on individuals not invested in the health and well-being of clients is the clients’ own lack of self-worth, treated trauma, and personal motivation. Despite the patient navigator’s best efforts, a client may refuse to initiate or complete treatment without intrinsic/extrinsic motivators.

The client [Bella] was homeless and living with her boyfriend when she contacted the navigator to be referred to inpatient rehab. Due to the lack of housing resources, this client lived with her boyfriend in a cheap motel for several weeks before being admitted to [treatment facility]. More than likely, this client would have been admitted sooner had she not been living with the BF under his influence during this time. (The patient navigator’s notes on Bella’s case)

Despite the best practices and effective strategies, this client [Ava] was not invested in going to rehab. She did not want to be away from her boyfriend or be in rehab for 90 days. Again, if a client is not invested, motivated, and ready to go, it is an uphill battle to get a client into rehab. (The patient navigator’s notes on Ava’s case)

2.2.2. Familial Support or Obstruction

The role of family support is similar in certain aspects to that of romantic partners, wherein the client often finds their family as a source of motivation or hesitancy to transition from substance use to a substance-free life. The patient navigator noted that parents, siblings, and distant cousins have been instrumental in providing clients with transportation to inpatient treatment facilities, housing between referral and treatment intake, and temporary guardians over their children while they receive treatment.

The client’s father was very concerned. On the day the client [Star] was scheduled to be admitted to [treatment facility], she continued to try to avoid admission. Her father tried to take her, but she would not come out of the apartment. She later showed up at the inpatient facility, but she was under the influence of drugs at the time. The persistence and support from the client’s father, navigator, and the staff at [treatment facility], this client was admitted and completed treatment. (The patient navigator’s notes on Star’s case)

Alternatively, a client’s family can also be influential in the client’s refusal to seek or attend treatment services. The fear of losing family support and care can be detrimental to a client’s substance use treatment journey, as the family unit or particular family members may be the client’s sole primary support system.

The client [April] was thankful and appreciative to the navigator and was motivated to seek treatment, however, she did not feel that she could go to inpatient rehab for the reason that she did not want any of their family to know she had substance use disorder. The navigator encouraged the client to reconsider, however, she opted to seek outpatient treatment. Navigator met with the client again the following day after the initial referral and the client continued to be tearful and apologetic for using any substances at all while pregnant. (The patient navigator’s notes on April’s case)

An aspect of SUD stigma, especially among pregnant and parenting women, is a child-fulfilling prophecy, whereby an individual exposed to a substance use lifestyle in early childhood is likely to repeat it as an adult, as displayed in Isabelle’s case. The caveat to this is that the interference of alternative, substance-free lifestyles, therapy, and—if needed—SUD treatments will often break the cycle, as portrayed through Clara’s case.

This client [Isabelle] has had a lot of traumas in her life. Her father died of a Heroin overdose when she was 9 years old. Her mother is also a user. (The patient navigator’s notes on Isabelle’s case)

The client [Clara] was very emotional and felt hopeless when the navigator met with her. She knew she had to do something to change her life permanently if she wanted to live and have a chance at being reunited with her son and be allowed to keep the baby when he/she was born. She had gone to Teen Challenge and had stayed sober for 1 1/2 years, however, her father passed away and she relapsed. She stated, “It’s so easy to get pulled back into using, it’s a vicious cycle”. She was born into the world of drugs with a father and grandfather who trafficked drugs and would take her with them on their drug dealings. She has suffered a lot of emotional and physical trauma and abuse throughout her life. (The patient navigator’s notes on Clara’s case)

The patient navigator acted as a pillar of emotional and tangible support for the PPW clients through flexible communicative hours and vocal advocacy for client circumstances. Many clients were referred to the patient navigator at times when they had little to no social support. Meeting an individual who offered non-judgmental, consistent encouragement throughout any stage of the treatment journey was a unique experience for each client, given the stigma and rejection they may encounter within the SUD treatment field and other contexts. The cycle of addiction feeds on hopelessness found through untreated trauma and abusive or impoverished situations. Offering clients a way to achieve safety and renewal through destigmatized empowering words, actions, and environments is vital to treatment and recovery success.

2.3. Institutional Contexts

2.3.1. Child Welfare and Judicial Court Systems

Stigma is a powerful barrier to treatment, especially among individuals who interact in a professional capacity with pregnant and parenting women with SUDs. Having a stilted or absent communicative pathway between organizations contributes to the lack of cohesive knowledge and understanding of how to properly treat women with SUD. Child Protective Services (CPS), drug court officials, and healthcare workers often play complex roles in the journeys of substance-using women. The empathy of caseworkers and judges varies based on personal perceptions (sometimes manifested as bias), knowledge of clients’ backgrounds, and client caseload. The patient navigator developed relationships and good rapport with county youth and drug court judges, attorneys, Child Protective Services caseworkers, homeless shelter administrators, treatment facility management, physicians, and more. Following these developments, the patient navigator introduced client advocacy in circumstances related and unrelated to court sessions. In all cases, the patient navigator acted as an essential liaison previously missing from interorganizational communication related to SUD treatment.

Client [Savannah] did not initiate inpatient treatment due to resistance from her CPS caseworker. Navigator spoke with the caseworker to inform her of the option for the client to go to rehab with the option for the baby to go with her at the facility or join her at a later time. The CPS caseworker discouraged the client from going to rehab. The client was willing and ready to go if that would help her regain custody of her baby. The caseworker did not encourage inpatient rehab, and actually made things very difficult for this client who was very compliant and cooperative with any requirements placed upon her to work toward reunification with her baby. (The patient navigator’s notes on Savannah’s case)

The introduction of a patient navigator is, in some locales, quite novel. The patient navigator instituted several networking methods months prior to and during the years of PPW program implementation. The time invested by the patient navigator in communicating the role of the PPW program (to facilitate linkage to SUD treatment) eventually allowed key individuals within SUD treatment and judicial agencies to learn the benefits of prioritizing this marginalized group. However, the initial struggle for attention, trust, and clear communication from partner organizations with the patient navigator was significant.

This case was challenging as a result of stigma and lack of communication from the caseworker to the client [Blaire], as well as the client feeling the caseworker was disrespectful to her. The client was frustrated because she did not realize that the mandate was for inpatient rehab and not outpatient rehab. By the time the caseworker made it clear to the client that she was mandated to be admitted to inpatient rehab, there was a one-week timeframe to get the patient admitted. The client reached out to the navigator at this point. The navigator reached out to other resources within [partner organization] to assist with the issues between the client and her caseworker, which was very helpful in changing the caseworker’s attitude. Moving quickly with this case was crucial, so navigator availability and flexibility to meet with the patient at a location convenient for her was key. Fortunately, [an inpatient facility] was able to admit this client into their facility the next week, preventing the client from losing custody of her children. (The patient navigator’s notes on Blaire’s case)

The role of CPS seems, at first glance, fairly straightforward: ensure the health and safety of all children. To do so, hospitals, courts, or concerned citizens may involve a CPS caseworker (or social worker) to remove a child from an unsafe environment and potentially to work towards parent–child reunification. As stigma and personal bias have been noted as impediments to parental SUD treatment, they can also act as barriers to family reunification, even as court and treatment requirements to regain child custody are met by clients.

This client [Savannah] was a self-referral. She met the navigator at a meeting and requested help to go to rehab because her baby was taken into CPS custody at birth. She is currently in the county youth court treatment program; however, she is frustrated because CPS has not been working with her well and there is a huge lack of communication between the client and her caseworker. The client reported to the navigator, “Last court date I said to the judge, I know what you want to see. Job, house, car ... and I’m going to go get that. And they looked at me ... and I sat there and smiled. Because I said I would, and I will”. (The patient navigator’s notes on Savannah’s case)

In several client cases, the patient navigator was the deciding factor for treatment pursuits and commitment. Having the patient navigator lend a compassionate, listening ear to the frustrations and worries of clients helped to waylay treatment concerns.

The client [Phoebe] was very appreciative and thankful for the help the navigator provided. She felt she was being forced to go by the court but was really not interested in going to rehab. She then decided to try to get a bed at a sober living facility and they did indeed accept her. (The patient navigator’s notes on Phoebe’s case)

2.3.2. Mental Health and Substance Use Treatment Centers

Facilities that offer support for women experiencing SUD are limited in number and capacity. Most inpatient clients served by the PPW patient navigator were required to wait several days or weeks for an available bed at their preferred facility. However, the diligent communication and inter-organizational networking of the patient navigator paved the way for several clients to receive immediate assistance from other facilities. A stable and safe environment for women with SUD is a persistent and pressing need. While inpatient facilities are the ultimate goal, the waiting period between referral and treatment intake leaves clients vulnerable to abuse or other health risks. Women’s and homeless shelters are part of the network created by the patient navigator. However, shelter employees’ and volunteers’ ill-treatment of clients, often stemming from personal issues, bias, or stigma, can obstruct the motivation and actions of clients to receive treatment.

Unfortunately, the inability to find the patient [Sierra] housing here on the coast while she was waiting for a bed at [inpatient treatment facility], was a huge barrier to getting this patient into rehab. The client was staying with her sister, which was an unstable/hostile environment for the client. The client and her six-month-old baby tested positive for COVID-19, making finding housing even more difficult. The client was given contact info for a women’s shelter in the county, however, when she called them she was treated rudely. The navigator contacted that facility and let the supervisor know what had happened. The client was encouraged to call them again, however, she did not want to call them after her initial experience with them. The client gave up and moved away. (The patient navigator’s notes on Sierra’s case)

There is a notable gap in care for women with SUD who are pregnant and mentally ill. Psychiatric facilities refuse to treat this population due to longstanding research that has proven, in some cases, how psychotropic medication can adversely affect both mother and child postpartum. Rather than offer a stable, albeit temporary, housing environment with integrated forms of therapy, most facilities are more likely to refuse any treatment altogether.

This client [Lori] was pregnant, homeless, and had a mental illness. The client was extremely paranoid and delusional, which made communication with the client extremely difficult. Contacting her via phone was difficult and depending on her mental state at the time, she may or may not talk with anyone. Every effort was made to engage the client and stay in contact with the client to increase the chances of her agreeing to be admitted to a rehab facility, however, this client was not mentally stable and therefore none of the residential rehabilitation facilities would accept her. The navigator diligently tried to locate a psychiatric facility that would accept her and stabilize her mentally. All of the psychiatric facilities, except for one, refused to treat her because she was pregnant. The representative for a psychiatric facility stated they would accept her, however, she was told they had no beds available when she went to the ER. The representative for the psychiatric facility did try to reach out to her to my knowledge, however, he was not assertive in trying to reach her and interview her for admission. Therefore, this client was not mentally stabilized until she was admitted to another facility at a later date. (The patient navigator’s notes on Lori’s [return referral] case)

Similarly, referring pregnant women with SUD but without mental health issues brings about another set of barriers. Inpatient treatment facilities often require that the client’s OB/GYN records monitoring the mother and child’s health be shared with facility administration for the client to receive treatment. In this study, several clients were denied or postponed SUD treatment due to the length of time it took between the primary care provider or OB/GYN office sharing medical records and the treatment facility receiving those records.

(1) Communication between facilities. There were issues with communication between each facility regarding the client’s mental status and insurance status.

(2) Lack of mental health treatment for this client because of pregnancy status.

(3) Lack of reliable transportation.

(4) Severe mental health issues with aggression; physically assaulting another patient, which led to her being committed and transferred to a state hospital. Despite efforts to encourage the client that rehab was the best option for her and her unborn child, the client was continuously adamant about leaving rehab. (The patient navigator’s notes on Terri’s case)

The patient navigator highlights that communication is often stilted or very limited between treatment or behavioral health and physical health facilities. The patient navigator often successfully acts as a liaison in communication not only among facilities but between facilities and the client (e.g., referrals to treatment centers, status updates from treatment centers or CPS/treatment caseworkers). Further communication also occurs between the patient navigator and key individuals in the client’s life (e.g., case worker, Child Protective Services worker, court judge, attorney). All communication is maintained with the understanding that the client receives the best treatment available. Additionally, communication promotes bettering clients’ life circumstances with the aid of their individual and agency-specific relationships. There is a general lack of support and understanding towards women who are pregnant and experiencing co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders.

3. Materials and Methods

Comprehensive qualitative analysis of detailed case notes on clients provided treatment referral services by the Mississippi OD2A Pregnant and Parenting Women’s patient navigator was used to conduct this study. The patient navigator’s case notes are part of a programmatic quality improvement initiative (evaluation) and were not created with the intent to hypothesize or create generalizable knowledge that qualifies as research under the U.S. Office of Human Research Protections standards. Instead, the case notes and role of the patient navigator are a baseline example for future replication, more systematic investigation, and contributions to the field of substance use disorder treatment. The case notes spanned all four years of the OD2A-sponsored Referral Enhancement Pilot Study’s (REPS) PPW program. The program, through the patient navigator, served a total of 60 parents (nearly all women) along the Mississippi Gulf Coast. The patient navigator was a registered nurse employed by a Mississippi family health center to manage referrals (making and receiving) for pregnant and parenting women with substance use disorders. Referral management included overseeing court-ordered inpatient or outpatient treatment, sober-living housing assistance, transportation assistance, as well as client contact with drug courts, child welfare services (e.g., CPS), treatment providers, and family members. The locations for treatment varied across Mississippi and, in some cases, extended to surrounding states as clients moved to where employment or family members were located, or as treatment beds became available. The majority of clients (55 of 60) were women, with three of the 55 female clients as return referrals. Each return referral was entered into the tracking document as a new client (though noted as a return) due to the closing of their initial case. Cases were closed through the client dropping out of the PPW program or completing treatment. All clients needed to be either pregnant or parenting at least one child under the age of 5 to be admitted into the PPW program. Female pregnant and parenting clients’ case notes were the only gender group analyzed for this study. The age and race/ethnicity of each client were not included in the data analysis as part of the deidentification process completed by the patient navigator prior to case note entry.

This study procured the reflections of the patient navigator based on 55 pregnant or parenting female clients’ SUD treatment journeys through the PPW program. Case notes were written from initial client contact to client treatment initiation, and, for some, treatment completion and parent-child reunification. Prior to client intake, the patient navigator was instructed to utilize a consent statement that featured core client consent elements (i.e., voluntary participation, the patient navigator sharing client case notes with program evaluators, deidentification of all case notes shared with program evaluators, client files outside of case notes never to be shared unless court-ordered). All patient navigator insights were shared via a tracking spreadsheet developed specifically for the PPW program (see Appendix A for a blank template example). The tracking spreadsheet allowed for deidentified client-specific rows to include detailed case notes, referral status, treatment status, and brief client quotes as recorded (written) by the patient navigator. All case notes were written with verbal client consent for deidentified sharing. Core elements of the verbal consent procedure are available from the corresponding author upon request. Data procured from the spreadsheet were organized into client gender (if male, the data were removed from analysis), date of referral to PPW program, number of children parented or birthed by the client, and all treatment case notes. Treatment case notes were analyzed according to type of treatment received (inpatient/outpatient) as noted by the patient navigator, treatment completion journey (i.e., started and stopped, completed, completed and returned), and client feedback on individuals or organizations with which the client interacted. Not every client case note reflected treatment specifics and thorough feedback, depending on the length of time in the PPW program. Consistent with applied research techniques, analyses were governed by two overarching sensitizing concepts, namely, facilitators and barriers to treatment initiation, retention, and completion. Attention was also given to thematic sub-patterns (e.g., family dynamics, treatment provider considerations) that emerged within each of these two overarching categories.

4. Discussion

A patient navigator’s role in linkage to substance use disorder (SUD) treatment for pregnant and parenting women (PPW) has not been significantly studied in prior research. Traditionally, patient navigators across healthcare settings (i.e., ambulatory care, diabetes, chronic disease, pediatrics) provide general navigation of the linkage to care (treatment) journey, with two primary areas of focus: a patient navigator who aims to reduce health disparities and a second who focuses on treatment and emotional support [22,23,24,25,26]. Our Mississippi-based study utilized the case notes of a patient navigator who blended health disparity reduction with treatment and emotional support goals. The primary functions of patient navigators generally consist of the following activities: (1) advocacy; (2) care coordination; (3) case monitoring and patient needs assessment; (4) community engagement; (5) education; (6) administration and research activities; (7) psychosocial support (8) navigation of treatment-related services; and (9) reduction of treatment and recovery success barriers [27]. The role of the patient navigator in the collection of client case notes and facilitation of client treatment is significant. The patient navigator prioritized obtaining verbal client consent related to sharing deidentified case notes with program evaluators for quality improvement purposes as well as the possibility of publication or presentation. Additional importance was given to client confidentiality, which was maintained by the patient navigator at all stages of the program. Our study supports previous literature that the patient navigator acts as an integral link in a disconnected health and justice system between treatment and reform entities, while our results also note critical areas for improvement across the SUD treatment sector.

Our study of the Overdose Data to Action Pregnant and Parenting Women program expands on well-documented tribulations, as well as successes, of working with marginalized women through three primary themes and six sub-themes. The first, individual factors, identify motivation to change as largely influential over treatment initiation and completion. Without an intrinsic motivation to overcome addiction, long-lasting sober living is unlikely. Likewise, emotional management can be a deciding factor for the successful completion of inpatient treatment, where behavioral issues pose a significant obstruction. The second theme, interpersonal relationships, builds on prior research that romantic partners and family members can exert considerable influence on pregnant and parenting women who have an SUD. Relationships with these key persons in primary social networks can encourage treatment completion through emotional and tangible support (transportation, stable housing) or, conversely, continued substance use through volatile circumstances (unsafe housing, intimate partner violence, partner substance procurement) [28,29,30]. Additionally, the presence of a family history of substance use, participation in illegal activities and other illicit behaviors, or physical violence were strong indicators of PPW clients’ substance use struggles. Such circumstantial histories acted as strong motivators for change and treatment compliance in several client cases, as supported by previous research findings [31,32,33]. Finally, institutional contexts include the presence of child welfare services and court systems, mental health centers, and substance use treatment facilities. These findings, along with specific barriers and success across client cases (see Table 2), are well supported by prior research and are elaborated below.

Table 2.

Barriers and successes identified by the patient navigator across client cases.

Our study results emphasize several barriers and successes (some known, others heretofore unknown) in the field of substance use treatment. Several studies have highlighted the barriers to care that pregnant and parenting women commonly encounter, such as fear of stigma, criminalization, or losing child custody [34,35,36]. The variety of treatment barriers is vast. However, rarely emphasized are each client’s specific needs unique to their situation that should be prioritized when organizing individual care pathways. Meeting these needs with compassion and empathy, and through consistent and persistent communication, is a determining factor in a client’s pursuit of treatment. A significant factor in the success of client treatment completion is needs-based referrals (i.e., keeping their child with them or allowing child visitations, providing individual or group therapy, psychiatric treatment, or medication-assisted treatment [MAT]). MAT is the most common of outpatient treatments, with medications such as methadone or buprenorphine promoted as safe for treating opioid use disorder (OUD) by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [37]. Evidence on long-term developmental outcomes for children after birth is often confounded by prenatal drug exposure and environmental factors [38,39,40]. The OD2A PPW program primarily worked with women in need of inpatient SUD treatment programs. However, the patient navigator was transparent in tailoring referral to care options based on client circumstances and wishes. For example, long-term inpatient treatment provided the intensive, supportive detox environment several clients needed, as well as offering a smooth transition to a second-step program. At times, the desires of the client (outpatient treatment over inpatient treatment) are in direct contrast with their needs or court orders. A careful analysis of case notes revealed a critical point that the patient navigator emphasized across several cases: if the client has no desire or motivation to overcome their SUD, they will not complete treatment and there is very little that outside entities (i.e., patient navigator, CPS/treatment case workers, court officials) can do to alter this mindset if it is entrenched. Yet, these motivations do not exist in a vacuum. Intrinsic and extrinsic factors are often connected. The staff at the partnered inpatient programs offered consistent support to clients that included legal aid (gaining unsupervised child visitation rights, protective orders lifted), emotional and mental (therapy or counseling outside of substance use counseling), and structure (safe shelter, house/treatment facility rules) (see Table 2). It is possible that personal resistance to change may stem from a lack of awareness of these resources. And this is precisely where the patient navigator became so crucial.

The primary goal of many courts and treatment facilities is overcoming substance use and promoting parent-child reunification. Through the patient navigator, that goal was strengthened and unified agencies across health and judicial sectors. However, alongside a general communication barrier between agencies prior to PPW program implementation, education on stigma and personal bias was lacking. During the program, the patient navigator noted several instances in which CPS, treatment caseworkers, and homeless shelter personnel hindered client admittance into treatment or a non-hostile living environment (see also Table 2). The construct of good mothering or hegemonic motherhood has been identified as a pivotal cultural norm in SUD treatment. Hegemonic motherhood standards support social stigma. Further, such standards are sometimes embedded in healthcare providers’ interactions with mothers with a substance-exposed pregnancy [41]. This situation underscores the need to develop an educational presentation for caseworkers and other professionals in the SUD treatment field. Educational efforts will act to reduce stigma against pregnant and parenting women and promote better communication with clients.

Additionally, there is a notable divide in care for mentally ill pregnant women with substance use disorders. Most rehabilitation facilities will not accept women who are pregnant and mentally ill. Likewise, psychiatric facilities will not accept these clients because it is inadvisable to treat pregnant women with psychotropic medication [42,43,44,45,46]. This notable cross-facility gap in care should be addressed in the future of healthcare and treatment systems. A significant improvement in treatment options for pregnant women with SUD and mental illness is needed. Alongside greater communication across agencies and treatment options for a variety of SUD clients, there is a notable lack of housing resources available for women prior to admittance into an inpatient rehab or sober living housing facility after completing rehabilitative services. The patient navigator often acted in the capacity of a social worker in obtaining transportation and housing for clients, alongside requesting current updates from treatment personnel and the clients themselves as the clients’ circumstances evolved. Communication with clients after discharging from treatment, never initiating treatment, or relapsing after treatment was crucial as several clients later returned for treatment or were court-mandated to undergo treatment. Consistent—and in some cases persistent—follow-up communication with clients is imperative to improve their success in completing treatment or returning to treatment when needed. These findings are supported by prior research that has underscored the influence of social relationships on women in SUD recovery, in which most clients describe a caring relationship with a service provider as helpful for initiating abstinence [47].

While the successes of this study contribute substantially to current research in the substance use field, future research may consider a few areas for improvement. Qualitative interviews with women in programs like this one may lend nuanced and detailed feedback from the perspective of care reception not wholly displayed in this study. Collecting consistent sociodemographic data such as age, race/ethnicity, religious involvement, marital status, education history, and residency or homeless status for clients may increase SUD understanding. Gathering more information on the history of client substance use exposure prior to substance use would also benefit knowledge gaps related to psychosocial elements of SUD. Additional research may also aim to consider gathering insights directly from SUD treatment and related entities mentioned in this study, such as county judges and attorneys, caseworkers, social workers, homeless shelter personnel, and treatment facility personnel. A mixed-methods approach to future research could also expand on the impact a multi-sector/patient navigator-led program would have on county or state-level overdose deaths, substance-dependent births, and substance-related arrests.

5. Conclusions

Overall, the Mississippi OD2A pregnant and parenting women (PPW) program debuted innovative patient navigation techniques in interactions with pregnant and parenting women who had a substance use disorder and, at times, a co-occurring mental illness. The lack of available widespread treatment options for pregnant women with substance use disorders is compounded by the strained or absent communication network between primary health, judicial, and treatment agencies. The introduction of a patient navigator as the liaison between agencies for pregnant and parenting women with substance use disorders offered valuable insights into linkage to care networks at large. The model presented in this study, whereby the patient navigator is not only a conduit for the referral of clients but also an advocate throughout the client’s treatment journey, is a viable option across communities in which pregnant and parenting women with substance use disorders are prevalent.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P.B. and K.K.; methodology, K.K. and J.P.B.; software, K.K; validation, K.K., J.P.B., C.N., J.D. and J.H.; formal analysis, K.K. and J.P.B.; investigation, J.P.B., C.N. and K.K.; resources, K.K.; data curation, K.K. and J.P.B.; writing—original draft preparation, K.K. and J.P.B.; writing—review and editing, K.K., J.P.B., C.N., J.D. and J.H.; visualization, J.P.B. and K.K.; supervision, J.P.B. and K.K.; project administration, J.P.B.; funding acquisition (as external project evaluator for this study, J.P.B.; as state implementation lead for overall OD2A project, J.H.). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding through a conventional research grant. Mississippi was a state recipient of an Overdose Data to Action grant provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (OD2A Award Number: 6 NU17CE924972-02-02). Grant activities were funded, and evaluators were compensated for effort expended through a flat fee that reflected a competitive market rate. The APC was waived by the journal.

Institutional Review Board Statement

As a program evaluation project that is not defined as research by the Office of Human Research Protections in the United States, this study did not require ethical approval. Therefore, no institutional review board (IRB) approval was necessary to complete this work. A determination letter exempting this project from IRB oversight was sought and secured. The lead author has served on various university IRBs for over 20 years and is well-versed in IRB requirements and protocols.

Informed Consent Statement

Because this study is based on program evaluation rather than formal research, standard IRB consenting procedures did not apply. Nevertheless, all participating clients were informed of the purpose of the patient navigator’s case notes and the voluntary nature of their participation in this project. Informed consent was secured at the time of PPW program client entry, which allowed for deidentified client case notes created by the patient navigator to be shared. As with any evaluation and study, clients could forego participating in an interview to share their life stories prior to and during their time with the OD2A Pregnant and Parenting Women program without loss of benefits to be accrued through program participation. The evaluators have taken all necessary steps to preserve data confidentiality and attend to related considerations.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to conduct this evaluation are proprietary and not suitable for public release. Please contact the lead author for more information about the data used to conduct this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the OD2A patient navigator, who exhibited both passion and perseverance in assisting pregnant and parenting women with substance use disorders in their treatment and for keeping detailed case notes throughout their journeys in the OD2A Pregnant and Parenting Women program. The interpretations offered in this paper are those of the study authors alone.

Conflicts of Interest

Three of the authors served as the project evaluators for this study and were compensated at a competitive market rate for the services rendered. A collaborative approach to evaluation was used to conduct this study. Data were collected by the organization that delivered the navigation services. The data were transmitted in raw form to the evaluators for coding, cleaning, and analyses. All data analyses, data interpretations, writing, and publication decisions were conducted solely by the authors.

Appendix A

Table A1.

A blank template of the follow-up tracker utilized by the patient navigator. “Dropdown” indicates a dropdown menu was used with the response options listed immediately below. All responses noted are examples and are not part of the original data set analyzed.

Table A1.

A blank template of the follow-up tracker utilized by the patient navigator. “Dropdown” indicates a dropdown menu was used with the response options listed immediately below. All responses noted are examples and are not part of the original data set analyzed.

| Reverse Referral If patient is reverse referred from treatment (back) to clinic, provide reverse referral date and notes; then begin new referral row for patient Otherwise, leave blank | |

| Navigator-CMT Techniques and Collaborations *Notes and Reflections* Specify best practices, ineffective strategies, improvement efforts, etc. | |

| Case Management Referral Notes Notes related to CMT involvement with client. (Formerly Case Management Team (CMT) Involved? dropdown: yes, no, unsure) | |

| Last Known Status of Patient *Notes* If there is any additional information on the patient, please provide it below | |

| Last Known Status of Patient [Dropdown] Treatment never initiated Treatment initiation only (<30 days) Treatment retention (30+ days) but not completion Treatment program completed Patient status unknown | |

| Last Known Status of Patient *Date Information Secured* mm/dd/yyyy | |

| Additional Follow-Up Information (e.g., patient experiences during treatment program) Please provide date and brief update | 8/4/2021—Patient reached treatment program midpoint and sees child via weekly onsite visits |

| Follow-Ups: *Date (mm/dd/yyy): Results/Notes* What follow-up information is available about the patient? | |

| Initial Referral Status Notes Provide referral status info below If client did not initiate treatment, indicate reason below | |

| Initial Referral Status [Dropdown] Resolved (select known outcome below) Resolved-Treatment initiation confirmed Resolved-Confirmed that patient did not initiate treatment Unresolved-Treatment initiation status unknown | |

| Navigator Call Attempts Date (mm/dd/yy) (Agency name and contact)–Notes | |

| Specify Other Referral Target Complete only for Column E Other | ABC Treatment Center |

| Referral Target [Dropdown] Region 12/Pine Belt Born Free/New Beginnings Fairland Harbor House Other (specify next column) | Other (specify next column) |

| Date of Referral mm/dd/yyyy | 9/1/21 |

| Age(s) of Child(ren) < 5 Specify age(s), separated by comma(s) 0 = None | 0 |

| Patient Type [Dropdown] Pregnant Parenting child < 5 Both pregnant and parenting | Pregnant |

| Spreadsheet Record Number Deidentified (not Clinic’s Medical Record #) Each record (row) = 1 treatment episode Thus, a relapse yields a new record (row) | Amy M. (Pseudonym) |

Note: All narrative between asterisks (i.e., *Date Information Secured*) denotes specific instructions for what should be reported by the patient navigator in the column rows. The “#” is shorthand for “number” for ease of review and reporting by the patient navigator.

References

- Prince, M.K.; Daley, S.F.; Ayers, D. Substance Use in Pregnancy. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542330 (accessed on 8 November 2023).

- Tandon, S.D.; Parillo, K.M.; Jenkins, C.; Duggan, A.K. Formative evaluation of home visitors’ role in addressing poor mental health, domestic violence, and substance abuse among low-income pregnant and parenting women. Matern. Child Health J. 2005, 9, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Health and Human Services; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Among Females Aged 12 and Older 2021; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt41854/NSDUH%20highlighted%20population%20slides/For%20NSDUH%20highlighted%20population%20slides/2021NSDUHPopulationSlidesFemales050323.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2023).

- Gao, Y.A.; Krans, E.E.; Chen, Q.; Rothenberger, S.D.; Zivin, K.; Jarlenski, M.P. Sex-related differences in the prevalence of substance use disorders, treatment, and overdose among parents with young children. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2023, 17, 100492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haight, S.C.; Ko, J.Y.; Tong, V.T.; Bohm, M.K.; Callaghan, W.M. Opioid use disorder documented at delivery hospitalization—United States, 1999–2014. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018, 67, 845–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhuri, P.K.; Gfroerer, J.C. Substance use among women: Associations with pregnancy, parenting, and race/ethnicity. Matern. Child Health J. 2009, 13, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIDA. Substance Use While Pregnant and Breastfeeding; US Department of Health and Human: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://nida.nih.gov/publications/research-reports/substance-use-in-women/substance-use-while-pregnant-breastfeeding (accessed on 8 November 2023).

- Forray, A. Substance use during pregnancy. F1000Research 2016, 5, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, L.; Arthur-Jordan, B.; Rice, J.; Tan, T. The risk of child removal by child protective services among pregnant women in medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder. J. Soc. Work Prac. Addict. 2022, 22, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, Z.; McConnell, K.; Jansson, L.M. Treatment for substance use disorders in pregnant women: Motivators and barriers. Drug Alcoh. Depend. 2019, 205, 107652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubberstey, C.; Rutman, D.; Schmidt, R.A.; Bibber, M.V.; Poole, N. Multi-service programs for pregnant and parenting women with substance use concerns: Women’s perspectives on why they seek help and their significant changes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bright, V.; Riddle, J.; Kerver, J. Stigma experienced by rural pregnant women with substance use disorder: A scoping review and qualitative synthesis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiff, D.M.; Jonathan, J.K.; Nielsen, T.C.; Myers, S.; Nolan, M.; Terplan, M.; Patrick, S.W.; Wilens, T.E.; Kelly, J. Assessing stigma towards substance use in pregnancy: A randomized study testing the impact of stigmatizing language and type of opioid use on attitudes toward mothers with opioid use disorder. J. Addict. Med. 2022, 16, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, A.; Miskle, B.; Lynch, A.; Arndt, S.; Acion, L. Substance use in pregnancy: Identifying stigma and improving care. Subst. Abus. Rehabil. 2021, 12, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stengel, C. The risk of being ‘too honest’: Drug use, stigma and pregnancy. Health Risk Soc. 2014, 16, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauber, S.; Ferayorni, F.; Henderson, C.; Hogue, A.; Nugent, J.; Alcantara, J. Substance use and depression in home visiting clients: Home visitor perspectives on addressing clients’ needs. J. Com. Psych. 2017, 45, 396–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dauber, S.; John, T.; Hogue, A.; Nugent, J.; Hernandez, G. Development and implementation of a screen-and-refer approach to addressing maternal depression, substance use, and intimate partner violence in home visiting clients. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 81, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.L.; Kenaszchuk, C.; Milligan, K.; Urbanoski, K. Levels and predictors of participation in integrated treatment programs for pregnant and parenting women with problematic substance use. BMC Pub. Health 2019, 19, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbanoski, K.; Joordens, C.; Kolla, G.; Milligan, K. Community networks of services for pregnant and parenting women with problematic substance use. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutman, D.; Hubberstey, C.; Poole, N.; Schmidt, R.A.; Van Bibber, M. Multi-service prevention programs for pregnant and parenting women with substance use and multiple vulnerabilities: Program structure and clients’ perspectives on wraparound programming. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarasoff, L.A.; Milligan, K.; Le, T.L.; Usher, A.M.; Urbanoski, K. Integrated treatment programs for pregnant and parenting women with problematic substance use: Service descriptions and client perceptions of care. J. Subs. Abus. Treat. 2018, 90, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budde, H.; Williams, G.A.; Winkelmann, J.; Pfirter, L.; Maier, C.B. The role of patient navigators in ambulatory care: Overview of systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBrien, K.A.; Ivers, N.; Barnieh, L.; Bailey, J.J.; Lorenzetti, D.L.; Nicholas, D.; Tonelli, M.; Hemmelgarn, B.; Lewanczuk, R.; Edwards, A.; et al. Patient navigators for people with chronic disease: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, K.J.; Valverde, P.; Ustjanauskas, A.E.; Calhoun, E.A.; Risendal, B.C. What are patient navigators doing, for whom, and where? A national survey evaluating the types of services provided by patient navigators. PEC 2018, 101, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loskutova, N.Y.; Tsai, A.G.; Fisher, E.B.; LaCruz, D.M.; Cherrington, A.L.; Harrington, T.M.; Turner, T.J.; Pace, W.D. Patient navigators connecting patients to community resources to improve diabetes outcomes. JABFM 2016, 29, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natale-Pereira, A.; Enard, K.R.; Nevarez, L.; Jones, L.A. The role of patient navigators in eliminating health disparities. Cancer 2011, 117, 3541–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, K.J.; Doucet, S.; Luke, A. Exploring the roles, functions, and background of patient navigators and case managers: A scoping review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 98, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asta, D.; Davis, A.; Krishnamurti, T.; Klocke, L.; Abdullah Krans, E.E. The influence of social relationships on substance use behaviors among pregnant women with opioid use disorder. Drug Alcoh. Dep. 2021, 222, 108665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, J.L.; Pierce, K.J.; Pennington, L.B.; Seiler, R.; Michael, J.; McNamara, D.; Zand, D. Social support, family empowerment, substance use, and perceived parenting competency during pregnancy for women with substance use disorders. Sub. Use Misuse 2018, 53, 2250–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, V.G.; O’Farrell, T.J.; Murphy, C.M.; Murphy, M.M.; Muchowski, P. Alcohol consumption and partner violence among women entering substance use disorder treatment. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2014, 28, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veseth, M.; Moltu, C.; Svendsen, T.S.; Nesvag, S.; Slyngstad, T.E.; Skaalevik, A.W.; Bjornestad, J. A stabilizing and destabilizing social world: Close relationships and recovery processes in SUD. J. Psychosoc. Rehab. Ment. Health 2019, 6, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiig, E.M.; Haugland, B.S.M.; Halsa, A.; Myhra, S.M. Substance-dependent women becoming mothers: Breaking the cycle of adverse childhood experiences. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2014, 22, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lander, L.; Howsare, J.; Byrne, M. The impact of substance use disorders on families and children: From theory to practice. Soc. Work Public Health 2013, 28, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessup, M.A.; Oerther, S.E.; Gance-Cleveland, B.; Cleveland, L.M.; Czubaruk, K.M.; Byrne, M.W.; D’Apolito, K.; Adams, S.M.; Braxter, B.J.; Martinez-Rogers, N. Pregnant and parenting women with a substance use disorder: Actions and policy for enduring therapeutic practice. Pr. Guide 2019, 67, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, R. Pregnant women and substance use: Fear, stigma, and barriers to care. Health Justice 2015, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, N. Treatment issues for alcohol- and drug-dependent pregnant and parenting women. Health Soc. Work 1994, 19, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SAMHSA. Evidence-Based, Whole-Person Care for Pregnant People Who Have Opioid Use Disorder; SAMHSA Advisory: Rockville, MD, USA, 2023. Available online: https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/pep23-02-01-002.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2023).

- Krans, E.E.; Kim, J.Y.; James, A.E., III; Kelley, D.; Jarlenski, M.P. Medication-assisted treatment utilization among pregnant women with opioid use disorder. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 133, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaman, S.L.; Isaacs, K.; Leopold, A.; Perpich, J.; Hayashi, S.; Vender, J.; Campopiano, M.; Jones, H.E. Treating women who are pregnant and parenting for opioid use disorder and the concurrent care of their infants and children: Literature review to support national guidance. J. Addict. Med. 2017, 11, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, A.M.; Nguyen, V.H. Medication-assisted treatment for pregnant women: A systematic review of the evidence and implications for social work practice. JSSWR 2015, 6, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, T.R.; Welborn, A.; Gringle, M.R.; Lee, A. Social stigma and perinatal substance use services: Recognizing the power of the good mother ideal. Contemp. Drug Probl. 2021, 48, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohen, D. Psychotropic medication in pregnancy. Adv. Psych. Treat. 2018, 10, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisolm, M.S.; Payne, J.L. Management of psychotropic drugs during pregnancy. BMJ 2016, 352, h5918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearlstein, T. Use of psychotropic medication during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Women Health 2013, 9, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieviet, N.; Dolman, K.M.; Honig, A. The use of psychotropic medication during pregnancy: How about the newborn? Neuropsych Dis. Treat 2022, 9, 1257–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, P.B.; Austin, M.P.V. Psychotropic medications in pregnant women: Treatment dilemmas. MJA 1998, 169, 428–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petterson, H.; Landheim, A.; Skeie, I.; Biong, S.; Brodahl, M.; Oute, J.; Davidson, L. How social relationships influence substance use disorder recovery: A collaborative narrative study. Subs. Abus. Res. Treat. 2019, 13, 1178221819833379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).