Understanding the Intersections of IPV and HIV and Their Impact on Infant Feeding Practices among Black Women: A Narrative Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

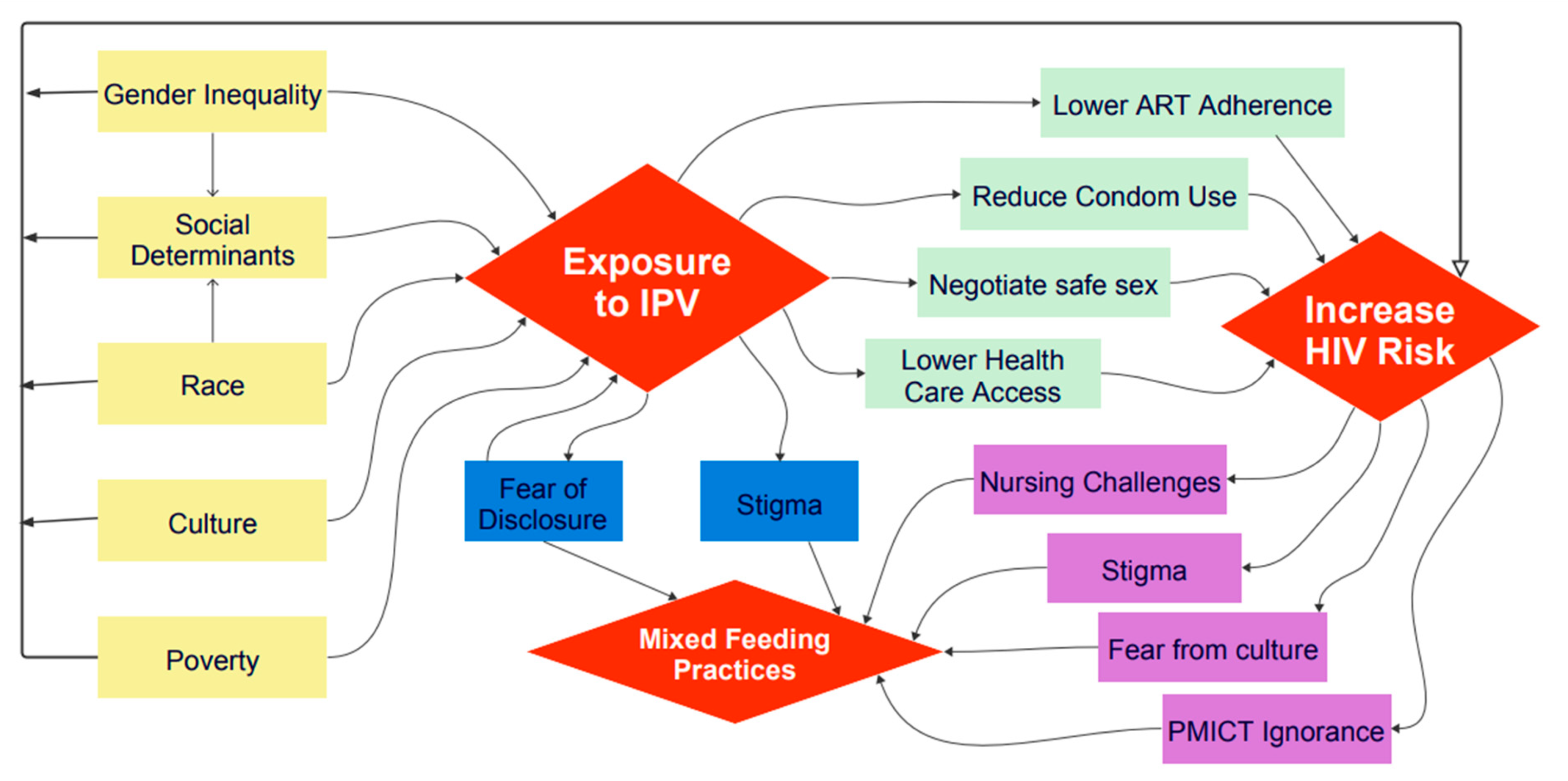

- Review the associated factors of IPV among Black women living with HIV;

- Assess the impact of IPV on infant feeding practices among Black women living with HIV;

- Examine how Black women living with HIV experience IPV in relation to infant feeding practices.

2. Methods

3. Findings

- (1)

- IPV against women;

- (2)

- HIV among Black women;

- (3)

- IPV and HIV-positive Black women;

- (4)

- Intersections of IPV, HIV, and infant feeding practices among Black women.

3.1. Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) against Women

3.2. HIV among Black Women

3.3. IPV and HIV-Positive Black Women

3.4. Intersection of IPV, HIV, and Breastfeeding Practices among Black Women

4. Discussion and Implications

5. Recommendations

6. Strengths and Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eggers del Campo, I.; Steinert, J.I. The Effect of Female Economic Empowerment Interventions on the Risk of Intimate Partner Violence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trauma Violence Abus. 2022, 23, 810–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Updates on HIV and Infant Feeding: The Duration of Breastfeeding, and Support from Health Services to Improve Feeding Practices among Mothers Living with HIV; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Gilbert, L.; Stoiscescu, C.; Goddard-Eckrich, D.; Dasgupta, A.; Richer, A.N.; Benjamin, S.; El-Bassel, N. Intervening on the Intersecting Issues of Intimate Partner Violence, Substance Use, and HIV: A Review of Social Intervention Group’s (SIG) Syndemic-Focused Interventions for Women. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2022, 33, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapiga, S.; Harvey, S.; Mshana, G.; Hansen, C.H.; Mtolela, G.J.; Madaha, F.; Watts, C. A Social Empowerment Intervention to Prevent Intimate Partner Violence against Women in a Microfinance Scheme in Tanzania: Findings from the MAISHA Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e1423–e1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, A.; Dunkle, K.; Willan, S.; Jama-Shai, N.; Washington, L.; Jewkes, R. Are Women’s Experiences of Emotional and Economic Intimate Partner Violence Associated with HIV-Risk Behaviour? A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Young Women in Informal Settlements in South Africa. AIDS Care 2019, 31, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, A.K.; Reyes, H.; Moodley, D.; Maman, S. HIV Positive Diagnosis during Pregnancy Increases Risk of IPV Postpartum among Women with No History of IPV in Their Relationship. AIDS Behav. 2018, 22, 1750–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV and African American People; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Slide Set: HIV Surveillance in Women; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018.

- Haddad, N.; Weeks, A.; Robert, A.; Totten, S. HIV in Canada—Surveillance report, 2019. Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 2021, 47, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tjepkema, M.; Christidis, T.; Olaniyan, T.; Hwee, J. Mortality Inequalities of Black Adults in Canada. Health Rep. 2023, 34, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Jasko, K.; Webber, D.; Kruglanski, A.W.; Gelfand, M.; Taufiqurrohman, M.; Hettiarachchi, M.; Gunaratna, R. Social Context Moderates the Effects of Quest for Significance on Violent Extremism. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 118, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia, E.; Lila, M.; Santirso, F.A. Attitudes Toward Intimate Partner Violence Against Women in the European Union: A Systematic Review. Eur. Psychol. 2020, 25, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuyuki, K.; Cimino, A.N.; Holliday, C.N.; Campbell, J.C.; Al-Alusi, N.A.; Stockman, J.K. Physiological Changes from Violence-Induced Stress and Trauma Enhance HIV Susceptibility Among Women. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2019, 16, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pemberton, J.V.; Loeb, T.B. Impact of Sexual and Interpersonal Violence and Trauma on Women: Trauma-Informed Practice and Feminist Theory. J. Fem. Fam. Ther. 2020, 32, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overstreet, N.M.; Willie, T.C.; Hellmuth, J.C.; Sullivan, T.P. Psychological Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Risk Behavior: Examining the Role of Distinct Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms in the Partner Violence–Sexual Risk Link. Women’s Health Issues 2015, 25, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J.; Wight, M.; Van Heerden, A.; Rochat, T.J. Intimate partner violence, HIV, and mental health: A triple epidemic of global proportions. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2016, 28, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabri, B.; Wirtz, A.L.; Ssekasanvu, J.; Nonyane, B.A.; Nalugoda, F.; Kagaayi, J.; Ssekubugu, R.; Wagman, J.A. Intimate partner violence, HIV and sexually transmitted infections in fishing, trading and agrarian communities in Rakai, Uganda. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, A.; Deschamps, M.M.; Dorvil, N.; Christophe, I.; Rosenberg, R.; Jean-Gilles, M.; Koenig, S.; Pape, J.W.; Dévieux, J.G. Association between intimate partner violence and HIV status among Haitian Women. Glob. Public Health 2019, 14, 1557–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leddy, A.M.; Zakaras, J.M.; Shieh, J.; Conroy, A.A.; Ofotokun, I.; Tien, P.C.; Weiser, S.D. Intersections of food insecurity, violence, poor mental health and substance use among US women living with and at risk for HIV: Evidence of a syndemic in need of attention. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenkorang, E.Y.; Asamoah-Boaheng, M.; Owusu, A.Y. Intimate partner violence (IPV) against HIV-positive women in Sub-Saharan Africa: A mixed-method systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse 2021, 22, 1104–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wudineh, F.; Damtew, B. Mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection and its determinants among exposed infants on care and follow-up in Dire Dawa City, Eastern Ethiopia. AIDS Res. Treat. 2016, 2016, 3262746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caleyachetty, R.; Uthman, O.A.; Bekele, H.N.; Martín-Cañavate, R.; Marais, D.; Coles, J.; Steele, B.; Uauy, R.; Koniz-Booher, P. Maternal exposure to intimate partner violence and breastfeeding practices in 51 low-income and middle-income countries: A population-based cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e1002921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, C.; Rakotomanana, H.; Komakech, J.; Stoecker, B. Maternal experience of intimate partner violence is associated with suboptimal breastfeeding in Malawi, Tanzania, and Zambia: Insights from DHS analyses. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, 3, nzz034-P10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, J.; Weaver, T.L.; Arnold, L.D.; Clark, E.M. The impact of intimate partner violence on women’s physical health: Findings from the Missouri behavioral risk factor surveillance system. J. Interpers. Violence 2017, 32, 3402–3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillum, T.L. The intersection of intimate partner violence and poverty in Black communities. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2019, 46, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, T.N. Recognizing complex trauma in child welfare-affected mothers of colour. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2019, 24, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontomanolis, E.N.; Michalopoulos, S.; Gkasdaris, G.; Fasoulakis, Z. The social stigma of HIV–AIDS: Society’s role. HIV/AIDS-Res. Palliat. Care 2017, 9, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joe, J.R.; Norman, A.R.; Brown, S.; Diaz, J. The intersection of HIV and intimate partner violence: An application of relational-cultural theory with Black and Latina women. J. Ment. Health Couns. 2020, 42, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, S.C.; Mittal, M. Safer Sex Self-Efficacy Among Women with Experiences of Intimate Partner Violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP1253–NP1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiff, D.M.; Nielsen, T.; Terplan, M.; Hood, M.; Bernson, D.; Diop, H.; Bharel, M.; Wilens, T.E.; LaRochelle, M.; Walley, A.Y.; et al. Fatal and nonfatal overdose among pregnant and postpartum women in Massachusetts. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 132, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampanda, K. Intimate partner violence against HIV-positive women is associated with sub-optimal infant feeding practices in Lusaka, Zambia. Matern. Child Health J. 2016, 20, 2599–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etowa, J.; Demeke, J.; Abrha, G.; Worku, F.; Ajiboye, W.; Beauchamp, S.; Taiwo, I.; Pascal, D.; Ghose, B. Social determinants of the disproportionately higher rates of COVID-19 infection among African Caribbean and Black (ACB) population: A systematic review protocol. J. Public Health Res. 2021, 11, jphr-2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadabadi, Z.; Najman, J.M.; Williams, G.M.; Clavarino, A.M.; d’Abbs, P. Gender differences in intimate partner violence in current and prior relationships. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 915–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, D.; Sharma, S.K.; Kukreti, S.; Singh, S.K. Attitude towards negotiating safer sexual relations: Exploring power dynamics among married couples in India. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2022, 55, 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Moreno, C.; Jansen, H.A.; Ellsberg, M.; Heise, L.; Watts, C.H. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women′s health and domestic violence. Lancet 2006, 368, 1260–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halim, N.; Beard, J.; Mesic, A.; Patel, A.; Henderson, D.; Hibberd, P. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and perinatal mental disorders in low and lower middle income countries: A systematic review of literature, 1990–2017. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 66, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coll, C.V.; Ewerling, F.; García-Moreno, C.; Hellwig, F.; Barros, A.J. Intimate partner violence in 46 low-income and middle-income countries: An appraisal of the most vulnerable groups of women using national health surveys. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardinha, L.; Maheu-Giroux, M.; Stöckl, H.; Meyer, S.R.; García-Moreno, C. Global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence against women in 2018. Lancet 2022, 399, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatcher, A.M.; Smout, E.M.; Turan, J.M.; Christofides, N.; Stöckl, H. Intimate partner violence and engagement in HIV care and treatment among women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS 2015, 29, 2183–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Gálvez, R.M.; Martín-Peláez, S.; Martínez-Galiano, J.M.; Khan, K.S.; Bueno-Cavanillas, A. Prevalence of intimate partner violence in pregnancy: An umbrella review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamu, S.; Abrahams, N.; Temmerman, M.; Musekiwa, A.; Zarowsky, C. A systematic review of African studies on intimate partner violence against pregnant women: Prevalence and risk factors. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Understanding and Addressing Violence against Women: Intimate Partner Violence; (No. WHO/RHR/12.36); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- Adimula, R.A.; Ijere, I.N. Psycho-social traumatic events among women in Nigeria. Madridge J. AIDS 2018, 2, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fiorentino, M.; Sow, A.; Sagaon-Teyssier, L.; Mora, M.; Mengue, M.T.; Vidal, L.; Kuaban, C.; March, L.; Laurent, C.; Spire, B.; et al. Intimate partner violence by men living with HIV in Cameroon: Prevalence, associated factors and implications for HIV transmission risk (ANRS-12288 EVOLCAM). PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adejuyigbe, E.; Orji, E.; Onayade, A.; Makinde, N.; Anyabolu, H. Infant feeding intentions and practices of HIV-positive mothers in southwestern Nigeria. J. Hum. Lact. 2008, 24, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeniyi, O.V.; Ajayi, A.I.; Issah, M.; Owolabi, E.O.; Goon, D.T.; Avramovic, G.; Lambert, J. Beyond health care providers’ recommendations: Understanding influences on infant feeding choices of women with HIV in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2019, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leshabari, S.C.; Blystad, A.; de Paoli, M.; Moland, K.M. HIV and infant feeding counselling: Challenges faced by nurse-counsellors in northern Tanzania. Hum. Resour. Health 2007, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Operto, E. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding exclusive breastfeeding among HIV-positive mothers in Uganda: A qualitative study. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2020, 35, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumbantoruan, C.; Kermode, M.; Giyai, A.; Ang, A.; Kelaher, M. Understanding women′s uptake and adherence in option B+ for prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission in Papua, Indonesia: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph Davey, D.; Farley, E.; Towriss, C.; Gomba, Y.; Bekker, L.G.; Gorbach, P.; Shoptaw, S.; Coates, T.; Myer, L. Risk perception and sex behaviour in pregnancy and breastfeeding in high HIV prevalence settings: Programmatic implications for PrEP delivery. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linguissi, L.S.G.; Sagna, T.; Soubeiga, S.T.; Gwom, L.C.; Nkenfou, C.N.; Obiri-Yeboah, D.; Ouattara, A.K.; Pietra, V.; Simpore, J. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV: A review of the achievements and challenges in Burkina-Faso. HIV/AIDS-Res. Palliat. Care 2019, 11, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Brest Feeding and HIV; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- Biomndo, B.C.; Bergmann, A.; Lahmann, N.; Atwoli, L. Intimate partner violence is a barrier to antiretroviral therapy adherence among HIV-positive women: Evidence from government facilities in Kenya. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zureick-Brown, S.; Lavilla, K.; Yount, K.M. Intimate partner violence and infant feeding practices in India: A cross-sectional study. Matern. Child Nutr. 2015, 11, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, I.; Tronick, E. The long shadow of violence: The impact of exposure to intimate partner violence in infancy and early childhood. Int. J. Appl. Psychoanal. Stud. 2020, 17, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsedal, D.M.; Yitayal, M.; Abebe, Z.; Tsegaye, A.T. Effect of intimate partner violence of women on minimum acceptable diet of children aged 6–23 months in Ethiopia: Evidence from 2016 Ethiopian demographic and health survey. BMC Nutr. 2020, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, L.M.; Nguyen, P.H.; Naved, R.T.; Menon, P. Intimate partner violence is associated with poorer maternal mental health and breastfeeding practices in Bangladesh. Health Policy Plan. 2020, 35 (Suppl. S1), i19–i29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etowa, J.; Nare, H.; Kakuru, D.M.; Etowa, E.B. Psychosocial Experiences of HIV-Positive Women of African Descent in the Cultural Context of Infant Feeding: A Three-Country Comparative Analyses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, E.L.; Geter, A.; Lima, A.C.; Sutton, M.Y.; Hubbard McCree, D. Effectively addressing human immunodeficiency virus disparities affecting US Black women. Health Equity 2018, 2, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkandawire, A.K.; Jumbe, V.; Nyondo-Mipando, A.L. To disclose or not: Experiences of HIV infected pregnant women in disclosing their HIV status to their male sexual partners in Blantyre, Malawi. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziersch, A.; Walsh, M.; Baak, M.; Rowley, G.; Oudih, E.; Mwanri, L. “It is not an acceptable disease”: A qualitative study of HIV-related stigma and discrimination and impacts on health and wellbeing for people from ethnically diverse backgrounds in Australia. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nydegger, L.A.; Dickson-Gomez, J.; Ko, T.K. Structural and syndemic barriers to PrEP adoption among Black women at high risk for HIV: A qualitative exploration. Cult. Health Sex. 2021, 23, 659–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, S.; Ion, A.; Elston, D.; Kwaramba, G.; Smith, S.; Carvalhal, A.; Loutfy, M. “Why aren′t you breastfeeding?”: How mothers living with HIV talk about infant feeding in a “breast is best” world. Health Care Women Int. 2015, 36, 883–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, M.; Hall, O.J.; Masters, G.A.; Nephew, B.C.; Carr, C.; Leung, K.; Griffen, A.; McIntyre, L.; Byatt, N.; Moore Simas, T.A. The effects of breastfeeding on maternal mental health: A systematic review. J. Women’s Health 2022, 31, 787–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapiriri, L.; Tharao, W.E.; Muchenje, M.; Masinde, K.I.; Siegel, S.; Ongoiba, F. The experiences of making infant feeding choices by African, Caribbean and Black HIV-positive mothers in Ontario, Canada. World Health Popul. 2014, 15, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekker, L.G.; Alleyne, G.; Baral, S.; Cepeda, J.; Daskalakis, D.; Dowdy, D.; Dybul, M.; Eholie, S.; Esom, K.; Garnett, G.; et al. Advancing global health and strengthening the HIV response in the era of the Sustainable Development Goals: The International AIDS Society—Lancet Commission. Lancet 2018, 392, 312–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, M.; Newman, L.; Ishikawa, N.; Laverty, M.; Hayashi, C.; Ghidinelli, M.; Pendse, R.; Khotenashvili, L.; Essajee, S. Elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and Syphilis (EMTCT): Process, progress, and program integration. PLoS Med. 2017, 14, e1002329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Global Plan towards the Elimination of New HIV Infections among Children by 2015 and Keeping Their Mothers Alive. 2011. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/20110609_JC2137_Global-Plan-Elimination-HIV-Children_en_1.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- World Health Organization & UNICEF. Guidance on Global Scale-Up of the Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission of HIV: Towards Universal Access for Women, Infants and Young Children and Eliminating HIV and AIDS among Children; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Kassa, G.M. Mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection and its associated factors in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, K.J.; Fowler, D.N.; Walters, M.L.; Doreson, A.B. Interventions that address intimate partner violence and HIV among women: A systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2018, 22, 3244–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, T. The intersection of intimate partner violence and HIV: Detection, disclosure, discussion, and implications for treatment adherence. Top. Antivir. Med. 2019, 27, 84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sileo, K.M.; Kintu, M.; Kiene, S.M. The intersection of intimate partner violence and HIV risk among women engaging in transactional sex in Ugandan fishing villages. AIDS Care 2018, 30, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCree, D.H.; Koenig, L.J.; Basile, K.C.; Fowler, D.; Green, Y. Addressing the intersection of HIV and intimate partner violence among women with or at risk for HIV in the United States. J. Women′s Health 2015, 24, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltz, A.R.; Lampe, F.C.; Bacchus, L.J.; McCormack, S.; Dunn, D.; White, E.; Rodger, A.; Phillips, A.N.; Sherr, L.; Clarke, A.; et al. Intimate partner violence, depression, and sexual behaviour among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men in the PROUD trial. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulerwitz, J.; Hughes, L.; Mehta, M.; Kidanu, A.; Verani, F.; Tewolde, S. Changing gender norms and reducing intimate partner violence: Results from a quasi-experimental intervention study with young men in Ethiopia. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wechsberg, W.M.; van der Horst, C.; Ndirangu, J.; Doherty, I.A.; Kline, T.; Browne, F.A.; Belus, J.M.; Nance, R.; Zule, W.A. Seek, test, treat: Substance-using women in the HIV treatment cascade in South Africa. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pract. 2017, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockman, J.K.; Jacquelyn, C. Intimate partner violence and its health impact on disproportionately affected populations. Incl. Minor. Impoverished Groups J. Women’s Health 2015, 24, 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavanaugh, C.; Ward, K. HIV/STI prevention interventions for women who have experienced intimate partner violence: A systematic review and look at whether the interventions were designed for disseminations. AIDS Behav. 2021, 25, 3605–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, A.; Jacobson, J.; Kerr Wilson, A. A global comprehensive review of economic interventions to prevent intimate partner violence and HIV risk behaviours. Glob. Health Action 2017, 10 (Suppl. S2), 1290427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parcesepe, A.M.; Cordoba, E.; Gallis, J.A.; Headley, J.; Tchatchou, B.; Hembling, J.; Soffo, C.; Baumgartner, J.N. Common mental disorders and intimate partner violence against pregnant women living with HIV in Cameroon: A cross-sectional analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorentino, M.; Sagaon-Teyssier, L.; Ndiaye, K.; Suzan-Monti, M.; Mengue, M.T.; Vidal, L.; Kuaban, C.; March, L.; Laurent, C.; Spire, B. Intimate partner violence against HIV-positive Cameroonian women: Prevalence, associated factors and relationship with antiretroviral therapy discontinuity—Results from the ANRS-12288 EVOLCam survey. Women’s Health 2019, 15, 1745506519848546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemons-Lyn, A.B.; Baugher, A.R.; Dasgupta, S.; Fagan, J.L.; Smith, S.G.; Shouse, R.L. Intimate partner violence experienced by adults with diagnosed HIV in the US. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 60, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orza, L.; Bass, E.; Bell, E.; Crone, E.T.; Damji, N.; Dilmitis, S.; Tremlett, L.; Aidarus, N.; Stevenson, J.; Bensaid, S. In women’s eyes: Key barriers to women’s access to HIV treatment and a rights-based approach to their sustained well-being. Health Hum. Rights 2017, 19, 155. [Google Scholar]

- Kabwama, S.N.; Bukenya, J.; Matovu, J.K.; Gwokyalya, V.; Makumbi, F.; Beyeza-Kashesya, J.; Mugerwa, S.; Bwanika, J.B.; Wanyenze, R.K. Intimate partner violence among HIV positive women in care-results from a national survey, Uganda 2016. BMC Women’s Health 2019, 19, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulrenan, C.; Colombini, M.; Howard, N.; Kikuvi, J.; Mayhew, S.H. Exploring risk of experiencing intimate partner violence after HIV infection: A qualitative study among women with HIV attending postnatal services in Swaziland. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e006907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampanda, K.M.; Rael, C.T. HIV status disclosure among postpartum women in Zambia with varied intimate partner violence experiences. AIDS Behav. 2018, 22, 1652–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, W.S.; Fletcher, F.E.; Akingbade, B.; Kan, M.; Whitfield, S.; Ross, S.; Gakumo, C.A.; Ofotokun, I.; Konkle-Parker, D.J.; Cohen, M.H.; et al. Quality of care for Black and Latina women living with HIV in the US: A qualitative study. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Closson, K.; McLinden, T.; Parry, R.; Lee, M.; Gibbs, A.; Kibel, M.; Wang, L.; Trigg, J.; Braitstein, P.; Pick, N. Severe intimate partner violence is associated with all-cause mortality among women living with HIV. AIDS 2020, 34, 1549–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motsoeneng, M. The experiences of South African rural women living with the fear of Intimate Partner Violence, and vulnerability to HIV transmission. FWU J. Soc. Sci. 2021, 15, 132–142. [Google Scholar]

- Goudet, S.; Griffiths, P.L.; Wainaina, C.W.; Macharia, T.N.; Wekesah, F.M.; Wanjohi, M.; Muriuki, P.; Kimani-Murage, E. Social value of a nutritional counselling and support program for breastfeeding in urban poor settings, Nairobi. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ejara, D.; Mulualem, D.; Gebremedhin, S. Inappropriate infant feeding practices of HIV-positive mothers attending PMTCT services in Oromia regional state, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2018, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariyo, T.; Jiang, Q. Intimate partner violence and exclusive breastfeeding of infants: Analysis of the 2013 Nigeria demographic and health survey. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2021, 16, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristizábal, L.Y.G.; Theme Filha, M.M. Physical violence against women by their intimate partner during pregnancy and its relationship with breastfeeding. Rev. Bras. De Saúde Matern. Infant. 2022, 22, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, H.; Francis, K.; Sconza, R.; Horn, A.S.; Peckham, C.; Tookey, P.A.; Thorne, C. UK mother-to-child HIV transmission rates continue to decline: 2012–2014. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 64, 527–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, H.; Rosenberg, E.S.; Holtgrave, D.R. Data-driven goals for curbing the US HIV epidemic by 2030. AIDS Behav. 2019, 23, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Guo, W.; Gui, X.; Liu, Y.; Yan, Y.; Feng, L.; Liang, K. Preventing mother to child transmission of HIV: Lessons learned from China. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Wang, H.; He, X.; Liu, J.; Wu, Q.; Wang, J. Investigation of prevention of mother to child HIV transmission program from 2011 to 2017 in Suzhou, China. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 18071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| #1. Intimate partner violence “Intimate partner violence” OR “IPV” OR “intimate partner abuse” OR “intimate violence” OR “partner violence” OR “partner abuse” OR “domestic abuse” OR “domestic violence” OR “wife abuse” OR “abuse of wife” OR “couple violence” OR “ martial violence” OR “intimate aggression” OR “dating violence” OR “ family violence” OR ”physical violence” OR “ physical abuse” OR “ gender violence” OR “ gender based violence” OR” gender and sexual violence” OR “sexual assault” OR “ sexual abuse” OR “emotional violence” “ emotional abuse” OR “ abused women” OR “women abuse” OR “ battered women” OR “physiological abuse” OR “physiological violence” OR “ sexual and gender based violence” OR “wife beating” OR “ spouse abuse” OR “dating violence” OR “GBV” OR “VAW” OR “sexual violence” OR “ relationship violence” |

| #2. Population “Black women” OR “African American women” OR “women of African descent” |

| #3. “HIV” OR “human immunodeficiency virus” |

| #4. Specific period “perinatal period” OR “ pregnancy” OR “ after pregnancy” OR “ postpartum” OR “ before pregnancy” OR “postnatal” OR “prenatal” OR “antenatal” OR “ maternal” or “pregnant” “ “ Breast feeding” OR “ infant feeding practices” |

| #5. “Intersection” OR “impact” OR “effects” OR “relationship” |

| #6. #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 AND #5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fseifes, M.; Etowa, J. Understanding the Intersections of IPV and HIV and Their Impact on Infant Feeding Practices among Black Women: A Narrative Literature Review. Women 2023, 3, 508-523. https://doi.org/10.3390/women3040039

Fseifes M, Etowa J. Understanding the Intersections of IPV and HIV and Their Impact on Infant Feeding Practices among Black Women: A Narrative Literature Review. Women. 2023; 3(4):508-523. https://doi.org/10.3390/women3040039

Chicago/Turabian StyleFseifes, Manal, and Josephine Etowa. 2023. "Understanding the Intersections of IPV and HIV and Their Impact on Infant Feeding Practices among Black Women: A Narrative Literature Review" Women 3, no. 4: 508-523. https://doi.org/10.3390/women3040039

APA StyleFseifes, M., & Etowa, J. (2023). Understanding the Intersections of IPV and HIV and Their Impact on Infant Feeding Practices among Black Women: A Narrative Literature Review. Women, 3(4), 508-523. https://doi.org/10.3390/women3040039