Abstract

Food insecurity and intimate partner violence are important determinants of health and wellbeing in southern Africa. However, very little research has attempted to investigate the association between them even though food insecurity is anticipated to increase in the region, mostly owing to climate change. The objective of this paper was to descriptively review peer reviewed studies that investigated the relationship between food insecurity and intimate partner violence in southern Africa. Literature searches were carried out in Scopus, Web of Science and PubMed databases without any time restriction. A total of five studies that investigated the association between food insecurity and intimate partner violence were identified in South Africa and Swaziland. Of these four studies used a cross-sectional design, and one employed a longitudinal design. Samples varied from 406 to 2479 individuals. No empirical studies were found for the remaining southern African countries of Angola, Botswana, Malawi, Namibia, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Lesotho, and Mozambique. Moreover, the reported findings indicated that there was an association between food insecurity and interpersonal violence (i.e., physical, psychological, and emotional) in the sub-region regardless the fact that the five studies used diverse measurements of both food insecurity and intimate partner violence.

1. Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is defined as violence that can occur between two people in a present/former intimate relationship. It exists worldwide regardless of culture or level of country development [1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) [2], IPV is defined as “behavior within a present/former intimate relationship that causes physical, sexual or psychological harm, including acts of physical aggression, sexual coercion, psychological abuse and controlling behaviors” [2]. Thus, the term helps to distinguish IPV from other types of domestic abuse such as child and elderly abuse, which are also frequent globally [2]. Additionally, although women may be violent in relationships with men, as well in same-sex partnerships, the most common perpetrators of violence in IPV are male intimate partners or ex-partners committing violence against women [3]. By contrast, men are far more likely to experience violent acts by strangers or acquaintances than by someone close to them [4].

It is now well acknowledged that IPV is a major human rights concern and that it is associated with an array of adverse physical (e.g., poor self-reported physical health, injuries), reproductive and sexual (e.g., increased risk for unintended pregnancies and abortions, miscarriage, sexually transmitted infections, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)) and psychological health outcomes (e.g., suicidal thoughts and attempts, depression, and anxiety) [5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Many household and community-level factors (e.g., education level, food insecurity (FI)) are associated with IPV, including poverty and other factors that contribute to the disempowerment of women. Food insecurity is an important risk factor for IPV, which is the central issue in this review.

The relationship between FI and IPV has been found to exist across the world [12,13,14]. For instance, a study in Nepal carried out among married women found that being food-insecure was “associated with higher odds of some types of IPV, specifically emotional and physical IPV”. In the study, accounting for women’s level of empowerment explained some of the relationship between FI and IPV [15]. Likewise, in California, Ricks and colleagues found that women with very low food security had fivefold increased odds of reporting IPV in the past year [16]. Moreover, in Ecuador, a mixed methodology study found that there was a potential link between FI and women’s experience of IPV including greater conflict and stress within couples and reduced household wellbeing [17]. Although few, some studies have investigated how FI in men is associated with men’s perpetration of IPV. For instance, conducting a multi-country study in five Asian countries, Fulu and colleagues found a bivariate relationship between FI and higher rates of men’s use of partner violence [18]. Another study, from Ivory Coast, found that stress originated from FI and that urban poverty was related to “IPV perpetration among men as they felt unable to meet their gendered role of providing for the family” [19]. There is now agreement that, in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) including those in southern Africa, women are likely to experience more FI than men [20], a situation that was further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic [21,22]. It is suggested that the relationship FI and IPV can be understood through three different pathways. Firstly, that economic abuse from a partner (through the denial of an adequate access to financial resources) might produce food insecurity [23]; secondly, those who detach themselves from abusive relations might end up relying on financial assistance and low-paid jobs for survival [23]. Therefore, these individuals might have problems in acquiring food as they will likely to be unable to afford it due to economic strain [24]; a situation that increases the risk of being food insecure. On the other hand, IPV is likely to expose individuals (e.g., women) to a greater risk for food insecurity that is also moderated by the abused individual’s current financial status [16,25,26]. It is suggested that compared with people with higher income, those with low-income, often are at greater risk of food insecurity after IPV [27,28]; thirdly, that a context that facilitates increased food insecurity is likely to also contribute to an increase in violence (e.g., poverty). Moreover, research has shown that poverty is strictly associated with both FI and IPV [29]. Furthermore, there are those who suggest that food insecurity can also be seen as an indicator of financial stress which has been found to precipitate IPV [30].

Although the United Nations (UN) General Assembly recently estimated that approximately 27.4 million people would experience further FI in the next 6 months in southern Africa [22] still very little research has focused on the potential relationship between FI and IPV in the sub-region. Therefore, this study aimed to review empirical studies that investigated the relationship between FI and IPV in southern Africa.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

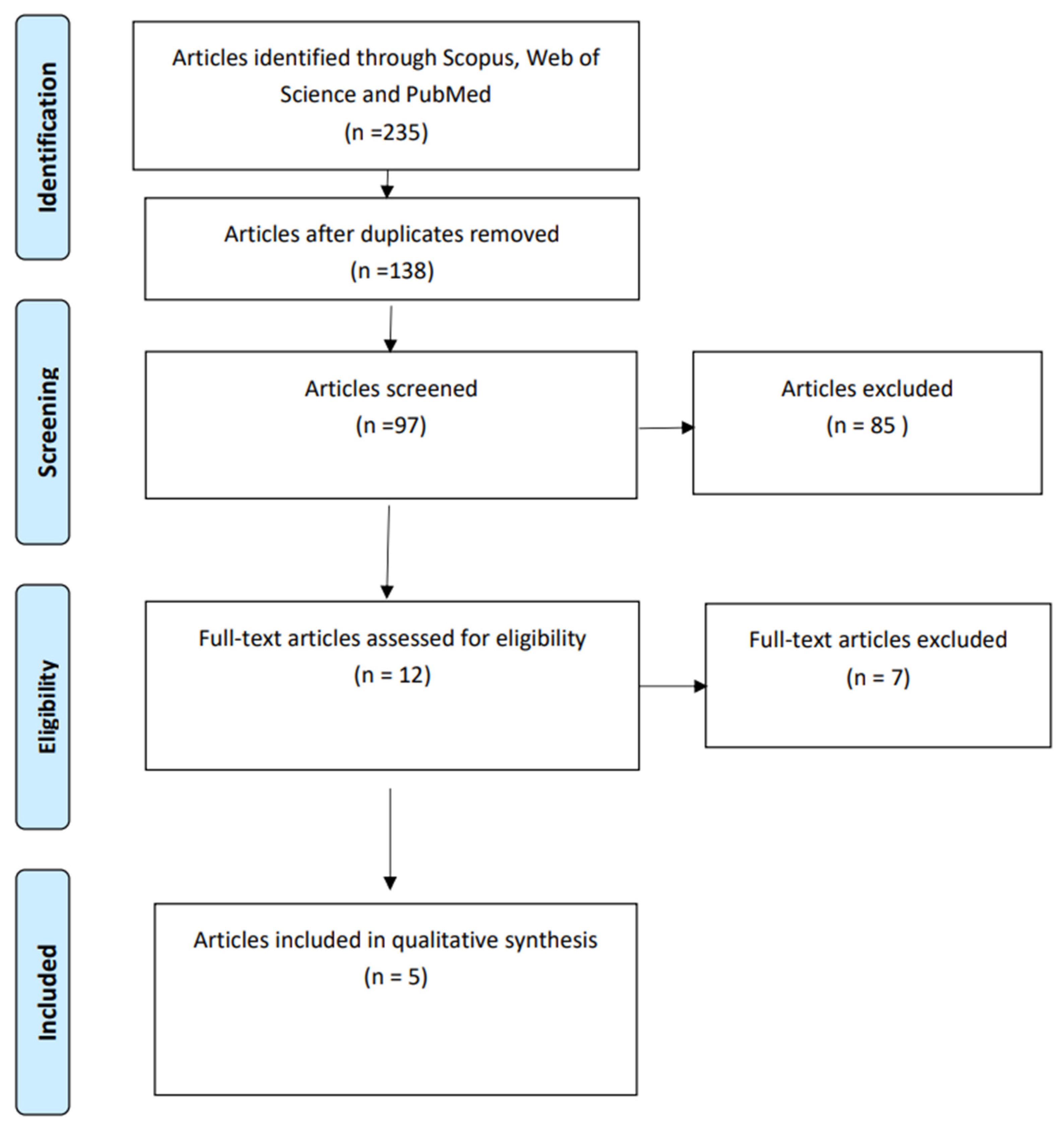

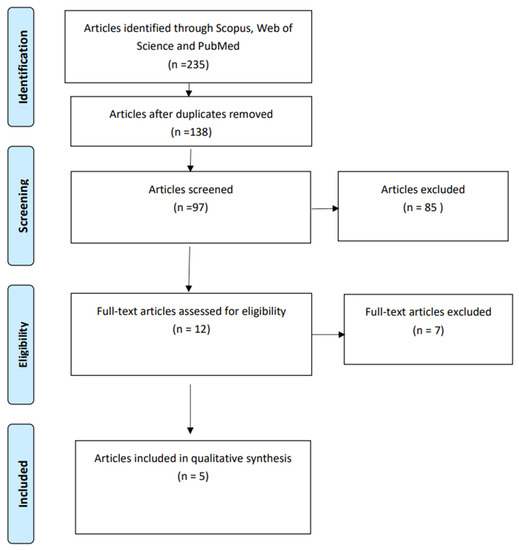

A systematic literature search in Scopus, Web of Science and PubMed was facilitated by three trained librarians at the University of Gävle. The systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [31] (Figure 1). The literature search searched for studies with no date limit to cover any published research that ever studied the relationship between FI and IPV in any gender group in southern Africa. The inclusion criteria were peer-reviewed studies written in the English language that had been conducted in southern African countries and focused on the relationship between FI and IPV. Exclusion criteria included publications in languages other than English as well those with exposures other than FI. Search terms included “food insecurity and IPV in southern Africa”, “food insecurity and domestic violence in southern Africa”, “food insecurity and gender-based violence in southern Africa”, “food insecurity and violence against women in southern Africa”, “food insecurity and violence against men in southern Africa”, “food insecurity and intimate partner violence against men in southern Africa”, “food insecurity and violence against girls in southern Africa” or “food insecurity and violence against pregnant women in southern Africa”. Furthermore, all the above terms were used to obtain searches in all the combinations mentioned above for each of the countries of the southern African region (Angola, Botswana, Malawi, Namibia, Lesotho, South Africa, Swaziland, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique).

Figure 1.

From: Moher, D.; Lberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6(6), e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097. [31]. For more information, visit www.prisma-statement.org (accessed 12 September 2022).

2.2. Article Selection and Assessment

A total of 235 articles were identified. Once duplicates had been removed, 138 articles remained to be thoroughly screened. These were exported to Mendeley Reference Management Software [32] for manual screening. First G.M. and J.S. read the full text of the twelve articles that were selected as eligible for the review. At this stage, seven articles were further excluded as they did not measure FI but used other measures (e.g., food poverty, food inadequacy). Food insecurity is measured at two levels of severity. In households with low food security, the hardships experienced are primarily reductions in dietary quality and variety. In households with very low food security, the hardships experienced are reduced food intake and skipped meals. Food poverty is defined as the “inability to access nutritionally adequate diet and the related impact on health, culture, and social participation” [33], while food inadequacy occurs when there is an inadequate dietary energy intake according to certain recommended levels [34].

Disagreement regarding inclusion and exclusion criteria was resolved between all the authors (G.M., J.d.C.F., E.M., J.S.) by considering the review’s main objective. A total of five articles met the inclusion criteria (see Figure 1).

3. Results

3.1. Countries Where the Studies Were Carried out and Study Design

The search identified a total of five studies that quantitatively investigated the association between FI and IPV in South Africa (four studies), and Swaziland (one study) [35,36,37,38,39]. Four studies used a cross-sectional design, and one employed a longitudinal design. The study samples varied from 406 to 2479 individuals. The studies are summarized in Table 1. There were no empirical studies investigating the relationship between FI and IPV found for Angola, Botswana, Malawi, Namibia, Lesotho, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique.

Table 1.

Summary of 5 studies included in the systematic review (Authors own processing of the results of the identified studies).

3.2. Reported Findings

Hatcher et al.’s study [35] investigated the pathway from FI to IPV perpetration among peri-urban men (n = 2006) in South Africa and employed a cross-sectional quantitative design. The study measured FI using the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS), with items including having no food in the house, going to sleep hungry, and going without food. The study’s results indicated that, among the studied partnered men, those who were food-insecure had double the odds of IPV perpetration [35]. Another study conducted in South Africa by Hatcher and colleagues [36] applied a longitudinal design (n = 2479) to assess the direction and strength of the association between FI and men’s perpetration of IPV and used the HFIAS to measure FI as in the study above [36]. To measure IPV, the study investigated occurrence of physical and sexual violence, in the past year, towards a current partner or ex-partner using the WHO Multi-Country Scale on violence against women. The authors created an outcome variable that simultaneously included hitting, choking, and forced sex. The response for the IPV outcome was “any IPV” versus “no IPV”. The study’s findings showed that food-insecure men had significantly increased odds of IPV perpetration at T0 and follow-up times T1 and T2, even after controlling for important co-variates [36].

Bloom et al.’s research in Swaziland (n = 406) was carried out through a cross-sectional quantitative study to investigate how agency and FI impacted violence-related outcomes among pregnant women [37]. Food insecurity was measured using “experiential food insecurity”, which meant that participants were asked if they had had experiences of being without adequate amounts of food in the past year. Violence was measured using the nine items of the WHO Violence Against Women Scale (WHO-VAWS). The IPV outcomes consisted of physical, emotional, and sexual violence. The study’s findings showed that there was a statistically significant association between FI and IPV, and also that high levels of FI were associated with an elevated risk of IPV [37]. Abrahams et al.’s South African study used a cross-sectional design to determine the relationship between common mental disorders and FI and experiences of violence among pregnant women (n = 885) during the COVID-19 lockdowns [38]. Food insecurity in the past 12 months was measured using the HIFAS scale. Intimate partner violence was measured using the Composite Abuse Scale, short form (CASR-SF), to assess violence experienced in the past 12 months. The IPV outcomes pertained to physical, psychological, and sexual abuse. Results of the study showed that almost half of the sample were food-insecure and that participants were subjected to physical, psychological, and sexual abuse. Interestingly, the study also found that sexual abuse occurred to a lesser extent than did physical and psychological abuse [38]. Barnett et al.’s study assessed the association between maternal trauma, IPV and IF in pregnant women (n = 902) using a cross-sectional quantitative design [39]. In the study, FI was measured using the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Household Food Security Scale, short form (HFSS-SF), to capture food hardships due to financial constraints. In the study, the measurement of FI included FI experienced by children in the household; and IPV was measured using the WHO Multi-Country Study Instrument which allowed the assessment of violence in the past 12 months and measured physical, psychological, and sexual abuse. Findings of the study indicated that there were higher rates of IPV (7–27%) in the study sample. Moreover, emotional IPV and childhood FI and depression partly mediated the relation between emotional IPV and FI as well as physical IPV and FI [29,39] (see Table 1). No studies investigating the relationship between FI and IPV were found for Angola, Botswana, Malawi, Namibia, Lesotho, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique.

3.3. Summary of the Reported Measurement of FI and IPV across the Five Studies

Three of the five studies used the “Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS)” to measure food insecurity, however two asked questions related to the past twelve months food insecurity, while the third asked for the past three months [35,36,38]. Bloom’s study used a different measure of FI called experiential food insecurity over a period of twelve months [37]. On the other hand, Barnet study measured FI in the past twelve months using the household food security scale (HFSS-SF) [39]. Furthermore, violence related outcomes were also measured using different instruments. For instance, two of the five studies used a IPV index of items related to physical and sexual violence in the past twelve months [35,36]. Bloom et al., study used the 9 item WHO Violence Against Women Scale to measure physical, emotional, and sexual violence [37]. Abrahams et al., and Barnet et al., study used The Composite Abuse Scale-Short Format (CAS-SF) to violence in the past twelve months, and the WHO Multicountry Study Instrument to measure physical, psychological and sexual abuse [38,39].

4. Discussion

Of the five empirical studies identified through the review, four were carried out in South Africa. One was conducted in Swaziland. Furthermore, all but one of the studies used a cross-sectional quantitative design. Only one of the two studies by Hatcher and colleagues [36] used a longitudinal design. Elsewhere, other studies among diverse population groups have used a cross-sectional qualitative design to investigate experience of household FI and IPV [40]. For instance, a study that investigated Colombian women’s experiences of household FI and IPV found that respondents related FI to IPV; and that women experienced more severe forms of FI during times of abuse [40].

The present review also found that the measurement of FI was made using different instruments. Three studies used the Household Food Insecure Access Scale (HFIAS), a very reliable and valid measure of food insecurity. According to some sources, the measurement of food security/insecurity has been a matter of continuous debate [41,42,43]. The reviewed studies used experience-based food insecurity measurement scales which are known to have some advantages such as (i) measuring directly the food insecurity experience as perceived by the affected respondents; (ii) to capture both the physical and psychologic dimensions of food insecurity; (iii) to map and understand the causes and consequences of food insecurity and hunger using the household as the unit of analysis; (vi) straightforward data collection, processing and analysis that is inexpensive which allows decentralization of data collection efforts; (v) the use of same scale, easy adaptation to local languages that facilitate its application in diverse cultural settings [44]. However, others argue that the experience-based food insecurity scales fail to capture issues related to food and water safety hazards caused by microbial and other contaminants [44]. Furthermore, others argue that it is difficult to establish cut-off points for classifying households into different levels of food insecurity since it is unknown if the cut-off points will end up being similar or not in different countries which in turn makes difficult to compare results globally [45,46,47,48,49]. Nevertheless, despite the different instruments used, all studies found moderate to high prevalence of FI across the studied samples [35,36,37,38,39].

The five studies also used different instruments to measure IPV, mostly asking about experience of violence in the past 12 months, and outcomes included physical, psychological, and sexual violence. The studies used scales such as the 9-item WHO Violence Against Women Scale (VAWS) and the Composite Abuse Scale Short Format (CAS-SF) to measure physical, psychological and sexual violence [50]. For instance, the 9-item WHO Violence Against Women Scale is one of the most valid instruments used to measure violence especially due to the fact that it was developed in cooperation with several networks and expert groups based on the original conflict tactics scales [50]. The CAS-SF is a brief and self-report measure of IPV experiences by women that has been found reliable and valid as well as suitable for population based studies [51]. It is argued that all currently existing assessment tools used to measure IPV fail to reflect underlying gendered dynamics [52] as they are descriptive and use tripartite categorization based on the mere appearance of the violent act, classifying partner violence as either physical, psychological/emotional, or sexual [52]. Moreover, others put forward the need to distinguish acts of IPV according to violence severity and intensity, situational influences, perpetrator’s motivations, societal patterns of gender- related dominance/control as well as the impacts and personal meanings of the abuse for both the perpetrator and the victim, to allow valid IPV assessment that takes the context of the violence into account [53,54].

Overall, the results of the review confirmed that the identified empirical studies found a statistically significant association between FI and IPV in southern Africa [35,36,37,38,39] (Table 1). This is in line with results from a systematic review of the relationship between FI and violence against women and girls (VAWG) in low- and middle-income settings (including Sub-Saharan Africa and southern Africa), which found that FI and VAWG were statistically and quantitatively related [14]. The authors of that review argued that their results suggested pathways in which FI led to household stress or tension across gender roles; they also reported that VAWG exposure led to FI, especially in situations where women were poorer after living in violent households [14]. Given that world hunger and severe FI have grown, especially after the onset of COVID-19, there is a likelihood that many women (and girls) will be further exposed to IPV. This is crucial for Sub-Saharan Africa and southern Africa specifically, as some of the countries in the region are experiencing internal conflicts in parallel, which are known to further exacerbate both FI and IPV [55].

4.1. Research Gaps and Practical Implications

The five studies identified by this review were carried out in two countries, mostly by South African researchers [35,36,37,38,39]. This finding is concerning as it shows that two countries of the sub-region experience substantial prevalence of both FI and IPV, and it is likely that FI and IPV are an issue also in the other countries of the sub-region [22]. From a policy and practice perspective this finding is important since there is a general expectation that climate change will exacerbate the prevalence of FI in the sub-region [56]. We agree with Hatcher and colleagues [14] that there is a need for evidence for efficient strategies that can jointly target FI and IPV in women and in girls. However, the same applies regarding violence against men, on which topic no study was found in this review. The review findings also have practical implications: Firstly, because FI and IPV are strictly linked to health (as determinants of health) [57,58], future studies in the identified countries need to investigate the potential dual burden caused by joint exposure to FI and IPV on physical and psychological health outcomes. Secondly, research on the association FI and IPV is warranted in Angola, Botswana, Malawi, Namibia, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Lesotho, and Mozambique to provide a better understanding of the magnitude of this relationship; as well as how they potentially affect population health outcomes in these countries. Thirdly, because both FI and IPV are endemic in Southern Africa and the expectation that FI will increase due to climate change, the understanding of their relation relationship will be crucial for the achievement of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), specifically goal 2 (End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable development and agriculture); goal 3 (Good health and wellbeing at all ages); and goal 5 (Achieve gender equality and empower women and girls) [59].

4.2. Limitations and Strengths

This review has limitations as it only includes peer-reviewed articles written in English. It is possible that non-English articles on the topic exist; and these have not been included. However, this review also has strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first descriptive and systematic review of the relationship between FI and IPV in the southern African region. Additionally, although most of the studies were carried out using cross-sectional designs, with only one applying a longitudinal design, the overall results indicate that there is an association between FI and IPV in the sub-region.

5. Conclusions

This systematic, and descriptive review found that there was empirical evidence of an association between FI and IPV in southern Africa. A total of five studies were identified, four of which were carried out in South Africa. No studies were found in the countries of Angola, Botswana, Malawi, Namibia, Lesotho, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique. The five identified studies were all quantitative and used cross-sectional and longitudinal design and a variety of instruments to measure FI and IPV. There is a need for the remaining countries in the sub-region to conduct their own studies to reach an understanding of the magnitude of the contribution of FI to IPV outcomes, as well as the consequences of both FI and IPV for health and wellbeing. Furthermore, comparative studies across all countries of the sub-region using similar instruments for FI and IPV measurements are needed. Given the dual burden represented by FI and IPV, for women in particular, policy makers need to ensure that research is a priority to provide evidence and facilitate potential interventions that will be crucial in work towards the achievement of UN SDGs 2, 3 and 5.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.M.; methodology, G.M. and J.S.; validation, G.M., J.d.C.F., E.M. and J.S.; formal analysis, G.M. and J.S.; investigation, G.M., J.d.C.F., E.M. and J.S.; data curation, G.M. and J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, G.M., J.S.; and writing review and editing G.M., J.d.C.F.; E.M. and J.S.; visualization, G.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Oskar Ahlén, Jonas Larsson and Sara Martinsson at the University of Gävle library for helping with the database searches. Furthermore, the authors would like to thank Cormac McGrath at Stockholm University for editing the revised version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| FI | food insecurity |

| USDA | United States Department of Agriculture |

| HFIAS | The Household Food Insecurity Access Scale |

| HFSS-SF | Short form of the Household Food Security Survey Module |

| IPV | intimate partner violence |

| CAS-SF | Short Format of the Composite Abuse Scale |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| 9-item WHO-VAWS | 9-item Violence Against Women Scale |

| CI | confidence interval |

| OR | odds ratio |

| CMD | common mental disorder |

| Cross-sectional design | Is a type of observational study design. In a cross-sectional study, the investigator measures the outcome and the exposures in the study participants at the same time |

| Longitudinal design | Is the study of a variable or group of variables in the same cases or participants over, a period of time, sometimes several years |

References

- Ellsberg, M.; Arango, D.J.; Morton, M.; Gennari, F.; Kiplesund, S.; Contreras, M.; Watts, C. Prevention of violence against women and girls: What does the evidence say? Lancet 2014, 385, 1555–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Preventing Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Against Women: Taking Action and Generating Evidence; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzeland; London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ellsberg, M.; Heise, L.; Watts, C.H.; Garcia-Moreno, C. Intimate partner violence and women’s physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence: An observational study. Lancet 2008, 371, 1165–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, E.G.; Dahlberg, L.L.; Mercy, J.A.; Zwi, A.B.; Lozano, L. World Report on Violence and Health. 2002. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42495/1/9241545615_eng.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2022).

- Sarkar, N.N. The impact of intimate partner violence on women’s reproductive health and pregnancy outcome. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2008, 28, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, A.C.; Wolfe, W.R.; Kumbakumba, E.; Kawuma, A.; Hunt, P.W.; Martin, J.N.; Bangsberg, D.R.; Weiser, S.D. Prospective study of the mental health consequences of sexual violence among women living with HIV in rural Uganda. J. Interpers. Violence 2016, 31, 1531–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenkorang, E.Y. Intimate Partner Violence and the Sexual and Reproductive Health Outcomes of Women in Ghana. Health Educ. Behav. 2019, 46, 969–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, A.C.; Tomlinson, M.; Comulada, W.S.; Rotheram-Borus, M.J. Intimate Partner Violence and depression symptom severity among South African women during pregnancy and postpartum: Population-based prospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1001943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, A.L.; Davis, K.E.; Arias, I.; Desai, S.; Sanderson, M.; Brandt, H.M.; Smith, P.H. Physical and Mental Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence for Men and Women. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 61, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, A.; Szoeke, C. The Effect of Intimate Partner Violence on the Physical Health and Health-Related Behaviors of Women: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Trauma Violence Abus. 2022, 23, 1157–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Mantas, L.; de Lemus, S.; Megías, J.L. Mental Health Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence Against Women in El Salvador. Violence Women 2021, 27, 2927–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramsky, T.; Watts, C.H.; Garcia-Moreno, C.; Devries, K.; Kiss, L.; Ellsberg, M.; Jansen, H.A.; Heise, L. What factors are associated with recent intimate partner violence? findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfouz, E.M.; Mohamed, E.S.; Alkilany, S.F.; Rahman, A.A. Food insecurity and intimate partner violence among rural women, Mania, Egypt. Egypt. J. Community Med. 2021, 39, 82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher, A.M.; Page, S.; van Eck, L.A.; Pearson, I.; Fielding-Miller, R.; Mazars, C.; Stöckl, H. Systematic review of food insecurity and violence against women and girls: Mixed methods findings from low- and middle-income settings. medRxiv 2022. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond-Smith, N.; A Conroy, A.; Tsai, A.C.; Nekkanti, M.; Weiser, S.D. Food insecurity and intimate partner violence among married women in Nepal. J. Glob. Health 2019, 9, 010412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricks, J.L.; Cochran, S.D.; Arah, O.A.; Williams, J.K.; Seeman, E.T. Food insecurity and intimate partner violence against women: Results from the California Women’s Health Survey. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 914–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buller, A.M.; Hidrobo, M.; Peterman, A.; Heise, L. The way to a man’s heart is through his stomach? A mixed methods study on causal mechanisms through which cash and in-kind food transfers decreased intimate partner violence. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulu, E.; Jewkes, R.; Roselli, T.; Garcia-Moreno, C. Prevalence of and factors associated with male perpetration of intimate partner violence: Findings from the UN Multi-country Cross-sectional Study on Men and Violence in Asia and the Pacific. Lancet Glob. Health 2013, 1, e187–e207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, L.F.; Gupta, J.; Shuman, S.; Cole, H.; Kpebo, D.; Falb, K.L. What Factors Contribute to Intimate Partner Violence Against Women in Urban, Conflict-Affected Settings? Qualitative Findings from Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. J. Urban Health 2016, 93, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjornlund, V.; Bjornlund, H.; van Rooyen, A. Why food insecurity persists in Sub-Saharan Africa: A review of existing evidence. Food Secur. 2020, 14, 845–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanVolkenburg, H.; Vandeplas, I.; Touré, K.; Sanfo, S.; Baldé, F.L.; Vasseur, L. Do COVID-19 and Food Insecurity Influence Existing Inequalities between Women and Men in Africa? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN General Assembly. UN Agencies Expand Operations in Southern Africa as Poor Harvests Deepen Food Insecurity. New York. UNGA. 2022. Available online: https://www.un.org/africarenewal/news/un-agencies-expand-operations-southern-africa-poor-harvests-deepen-food-insecurity (accessed on 26 September 2022).

- Broża-Grabowska, P. Women’s experience of poverty in context of power inequality and financial abuse in intimate relationship. Soc. Work Soc. 2011, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lentz, E.C. Complicating narratives of women’s food and nutrition insecurity: Domestic violence in rural Bangladesh. World Dev. 2018, 104, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, E.M. Economic Abuse and Intra-household Inequities in Food Security. Can. J. Public Health 2006, 97, 258–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackerson, L.K.; Subramanian, S.V. Domestic violence and chronic malnutrition among women and children in India. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2008, 167, 1188–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, C.T.; Mclanahan, S.S. Why are cohabiting relationships more violent than marriages? Demography 2006, 43, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bair-Merritt, M.H.; Holmes, W.C.; Holmes, J.H.; Feinstein, J.; Feudtner, C. Does Intimate Partner Violence Epidemiology Differ Between Homes with and Without Children? A Population-Based Study of Annual Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors. J. Fam. Violence 2008, 23, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, F.; Salam, R.A.; Lassi, Z.S.; Das, J.K. The Intertwined Relationship Between Malnutrition and Poverty. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, L.S.; Parker, E.; Peek-Asa, C. 10 Financial stress and intimate partner violence perpetration among young men and women. Inj. Prev. 2015, 21, A4–A4.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendeley Reference Management Software, Version 19.8; Elsevier: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2020.

- Friel, S.; Conlon, C. Policy Response to Food Poverty in Ireland; Combat Poverty Agency: Dublin, Ireland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Slater, B.; Marchioni, D.L.; Fisberg, R.M. Estimating prevalence of inadequate nutrient intake. Rev. Saude Publica 2004, 38, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher, A.M.; Stöckl, H.; McBride, R.-S.; Khumalo, M.; Christofides, N. Pathways from Food Insecurity to Intimate Partner Violence Perpetration Among Peri-Urban Men in South Africa. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 56, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatcher, A.M.; Neilands, T.B.; Rebombo, D.; Weiser, S.D.; Christofides, N.J. Food insecurity and men’s perpetration of partner violence in a longitudinal cohort in South Africa. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health 2022, 5, e000288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, B.E.; Wagman, J.A.; Dunkle, K.; Fielding-Miller, R. Exploring intimate partner violence among pregnant Eswatini women seeking antenatal care: How agency and food security impact violence-related outcomes. Glob. Public Health 2020, 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrahams, Z.; Boisits, S.; Schneider, M.; Prince, M.; Lund, C. The relationship between common mental disorders (CMDs), food insecurity and domestic violence in pregnant women during the COVID-19 lockdown in Cape Town, South Africa. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2022, 57, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, W.; Pellowski, J.; Kuo, C.; Koen, N.; Donald, K.A.; Zar, H.J.; Stein, D.J. Food-insecure pregnant women in South Africa: A cross-sectional exploration of maternal depression as a mediator of violence and trauma risk factors. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e018277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardsmeier, B. Experiences of Household Food Insecurity and Intimate Partner Violence in Rural Colombia: Qualitative Analysis of Female Smallholder Farmers. Matser’s Thesis, Emory University, Rhodes, Greece, 2017. Available online: https://etd.library.emory.edu/concern/etds/v405sb12n?locale=fr (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Masset, E. A review of hunger indices and methods to monitor country commitment to fight hunger. Food Policy 2011, 36, S102–S108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battersby, J. Urban Food Security and the Urban Food Policy Gap. Paper Presented at “Towards Carnegie III Conference, University of Cape Town. 7 September 2012. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Urban-food-security-and-the-urban-food-policy-gap-Battersby/3f07671f6fd407992a5d3cc58897b0379aaf9266 (accessed on 14 October 2022).

- Hayson, G.; Tawodzera, G. Measurement drives diagnosis and response: Gaps in transferring food security assessment to urban scale. Food Policy 2018, 74, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Escamilla, R.; Segall-Corrêa, A.M. Food insecurity measurement and indicators. Rev. Nutr. Campinas 2008, 21, 15s–26s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Agriculture-USDA; Economic Research Service. Food Security/Hunger Core Module. Available online: http://www.ers.usda.gov/Briefing/FoodSecurity/surveytools/core0699.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Coates, J.; Frongillo, E.A.; Rogers, B.L.; Webb, P.; Wilde, P.E.; Houser, R. Commonalities in the experience of household food insecurity across cultures: What are measures missing? J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 1438S–1448S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Segall-Corrêa, A.M.; Kurdian- Maranha, L.; Sampaio, M.d.F.; Marin-Leon, L.; Panigassi, G. An adapted version of the U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Insecurity module is a valid tool for assessing household food insecurity in Campinas, Brazil. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 1923–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Parás, P.; Dolkar, T.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H. The USDA food security module is a valid tool for assessing household food insecurity in Mexico City. EB 2005 meetings, San Diego, California. Faseb. J. 2005, 19, 748.3. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Randolph, S.; Hathie, I.; Gaye, I. Adaptation and validation of the USDA food security scale in rural Senegal [Abstract # 104.1]. Faseb. J. 2004, 18, A106. [Google Scholar]

- Nybergh, L.; Taft, C.; Krantz, G. Psychometric properties of the WHO Violence Against Women instrument in a female population- based sample in Sweden: A cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2013, 3, 2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford-Gilboe, M.; Wathen, C.N.; Varcoe, C.; MacMillan, H.L.; Scott-Storey, K.; Mantler, T.; Hegarty, K.; Perrin, N. Development of a brief measure of intimate partner violence experiences: The Composite Abuse Scale (Revised)-Short Form (CASR-SF). BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Fernández, M.A.; Goberna-Tricas, J.; Payá-Sánchez, M. Characteristics and clinical applicability of the validated scales and tools for screening, evaluating and measuring the risk of intimate partner violence. Systematic literature review (2003–2017). Aggress. Violent Behav. 2019, 44, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.P.; Ferraro, K.J. Research on domestic violence in the 1990s: Making distinctions. J. Marriage Fam. 2000, 62, 948–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogat, G.A.; Levendosky, A.A.; Von Eye, A. The Future of Research on Intimate Partner Violence: Person-Oriented and Variable-Oriented Perspectives. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2005, 36, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FEW SNET. Southern Africa Food Security Outlook October 2021 to May 2022. Famine Early Warning Systems Network. 2022, pp. 1–5. Available online: https://fews.net/sites/default/files/documents/reports/SOUTHERN%20AFRICA_Food_Security_Outlook_%20October%202021_Final.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Baptista, D.; Farid, M.; Fayad, D.; Kemore, L.; Lanci; Mitra, P.; Muehlschlegel, T.; Okou, C.; Spray, J.; Tuitoek, K.; et al. Climate Change and Food Insecurity in Sub-Saharan Africa; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Winnersjö, R.; Ponce de Leon, A.; Soares, J.F.; Macassa, G. Violence and self-reported health: Does individual socioeconomic position matter? J. Inj. Violence Res. 2012, 4, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, M.; Panzera, A. Food insecurity: A key determinant of health. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2021, 35, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stansfield, J. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A Framework for Intersectoral Collaboration, Whanake: The Pacific. J. Community Dev. 2017, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).