Abstract

Background: Overweight and obesity in adults are on the rise around the world, contributing significantly to noncommunicable disease deaths and disability. Women bear a disproportionate burden of obesity when compared with men, which has a negative impact on their health and the health of their children. The objective of this study was to examine the country-level prevalence of overweight and obesity among women of reproductive age in sub-Saharan countries. Methods: A total of 504,264 women from 2006 to 2021 were examined using cross-sectional Demographic and Health Surveys data. The outcome variables for this study include: (a) women who are overweight according to body mass index (BMI) (25.0–29.9kg/m2); (b) women who are obese according to BMI (≥30.0 kg/m2). Results: Eswatini (28%), Mauritania (27%), South Africa (26%), Gabon, Lesotho and Ghana (25% each) had the highest prevalences of overweight. In addition, obesity prevalence was highest in South Africa (36%), Mauritania (27%), Eswatini (23%), Lesotho (20%), Gabon (19%) and Ghana (15%), respectively. Overweight and obesity were more prevalent among older women, those living in urban areas, women with secondary/higher education and those in the richest household wealth quintiles. Conclusion: The risk factors for overweight and obesity, as well as the role that lifestyle changes play in preventing obesity and the associated health risks, must be made more widely known. In order to identify those who are at risk of obesity, we also recommend that African countries regularly measure their citizens’ biometric characteristics.

1. Background

Overweight and obesity are a major public health concern due to their links with numerous chronic diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, diabetes, stroke and cancer [1,2]. Adult overweight and obesity have increased globally, with obesity rates almost three times higher than in 1975 [2]. Over 1.9 billion adults worldwide aged 18 and older were estimated to be overweight or obese in 2016, with the prevalences of these conditions being 26% and 13%, respectively, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) [2]. Over 70% of adults in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are overweight or obese [3]. Furthermore, overweight and obesity are responsible for 2.4 million deaths and 70.7 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in women [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines an individual as overweight if their body mass index (BMI) is above 25 and obese if their BMI is ≥ 30 (2).

Adult overweight and obesity have become much more common in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [1,3,4], from 28.4% in 2000 to 41.7% in 2016, or an estimated 429 million people [1]. All SSA countries are considered LMICs [5]. Women are disproportionately affected by the rise in obesity, which is a result of demographic shifts, economic expansion and technological advancement in resource-constrained environments [6]. This is because women are more susceptible than men due to biologically different rates of growth and behavioral factors such as a lack of physical activity [6]. Due in part to dietary change and an increase in sedentary behavior, especially in urban areas, obesity and overweight among women of reproductive age (WRA) are on the rise in LMICs [6]. WRA include women aged 15–49 years [7].

An increasing trend in overweight and obesity among WRA in SSA has been shown by data from existing studies [3,4]. Studies conducted in SSA have shown an obesity prevalence ranging between 10 and 39% among WRA [3,4,8,9], with rates higher than 30% in Egypt [4], Zimbabwe [9] and South Africa [3,10]. The prevalence of overweight and obesity among WRA varies by demographic data such as socioeconomic status age, marital status, race/ethnicity, parity, education levels and wealth status [3,4,8,11,12,13]. Different studies conducted in SSA countries reported that factors such as increased age [9,10,12,13,14], urban residence [8,9,10,13,15], being married [9,13,14], being employed [9], increased parity [12], higher wealth status [8,9,10,11,12,14,15], higher educational levels [8,11,12,13,14,15], race/ethnicity, frequent television watching [3,12,16], sedentary lifestyle and alcohol use [9] correlated with higher odds of overweight and obesity in WRA. In SSA, obesity is linked with affluence; excess weight and obesity are generally concentrated among women with higher socioeconomic status (higher education levels and the wealthy) [8,9,13,14,15]. Notable, the observation of socioeconomic status association with overweight and obesity among women is different from those in high-income countries, where overweight and obesity are generally concentrated among women with lower socioeconomic status (low education levels and the poor) [17].

The findings from this study would be helpful to regional, national, and sub-national stakeholders in health care systems, decision and policy makers and governments in designing effective programmes to address the incidence of overweight and obesity among women aged 15–49 years. The findings may also set in motion a new area of future research including but not limited to looking at the implications of overweight and obesity for sleep quality and disease or injury recovery and investigating health issues exacerbated by overweight and obesity among women. The objective of this study was to investigate the variations in overweight and obesity among WRA (15–49 years) in SSA countries.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

In this study, we conducted a secondary data analysis using a large public dataset. A total of 504,264 women from 2006 to 2021 were examined using cross-sectional Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) data in SSA countries. In order to collect data, the DHS uses multistage cluster stratified sampling. Using the stratification method, respondents are divided into groups according to their geographic location, which is frequently spanned by their place of residence: urban versus rural. The population is divided into first-level strata, which are further subdivided into second-level strata, and so on, using a multilevel approach. The DHS has two levels of stratification: geographical region and urban/rural. The countries examined in this study include: Benin (n = 15,928), Burkina Faso (n = 17,087), Burundi (n = 17,269), Cameroon (n = 14,677), Chad (n = 17,719), Comoros (n = 5329), Congo (n = 10,819), Congo Democratic Republic (n = 18,827), Cote d’Ivoire (10,060), Eswatini (n = 4987), Ethiopia (n = 15,683), Gabon (n = 8422), Gambia (11,865), Ghana (n = 9396), Guinea (n = 10,874), Kenya (n = 31,079), Lesotho (6621), Liberia (n = 8065), Madagascar (n = 17,375), Malawi (24,562), Mali (n = 10,519), Mozambique (n = 13,745), Namibia (n = 10,018), Niger (n = 11,160), Nigeria (n = 41,821), Rwanda (14,634), Sao Tome and Principe (n = 2615), Senegal (n = 15,688), Sierra Leone (n = 15,574), South Africa (n = 8514), Tanzania (n = 13,266), Togo (n = 9480), Uganda (n = 18,506), Zambia (16,411) and Zimbabwe (n = 9955). DHS data is publicly available and can be found at http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm (accessed on 10 July 2022).

These surveys have been carried out since 1984 and are repeated every 5 years in over 85 different countries. The results from different countries can be compared because different countries use the same sampling design and data collection strategy. The DHS was originally intended to supplement the demographic, family planning and fertility data gathered by the World Fertility Surveys and Contraceptive Prevalence Surveys, but it has quickly emerged as the most crucial source of population surveillance data for tracking population health indices, especially in settings with limited resources. The DHS gathers data on immunizations, maternal and infant mortality, fertility, intimate partner violence, female genital mutilation, nutrition, lifestyle, infectious and noninfectious diseases, family planning, water and sanitation, and other health-related topics. DHS is excellent at gathering data because it offers proper interviewer training, nationwide coverage, a uniform data collection tool and operational definitions of topics that are easy for policy makers and decision makers to understand. Epidemiological studies that calculate prevalence, trends and inequities can be produced using DHS data. Information about DHS was previously made public [18]. Figure 1 shows the location of SSA countries as presented by a previous study [19]. Geographically speaking, the area of the African continent south of the Sahara Desert is known as sub-Saharan Africa. These are all resource-constrained settings and commonly classified as LMICs [5]. Please see Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Location of sub-Saharan countries.

2.2. Selection and Measurement of Variables

2.2.1. Outcome

The outcome variables for this study include: (a) women who are overweight according to BMI (25.0–29.9 kg/m2); (b) women who are obese according to BMI (≥30.0 kg/m2).

2.2.2. Independent Variables

Age: 15-24/25-34/35-49 years; residential status: urban/rural; education: no education/primary versus secondary/higher; household wealth quintile: lowest, second, middle, fourth and highest. The wealth index was retained from the DHS as it is directly available in the dataset [20]. The asset ownership indicators were used to create a linear index that was then weighted using principal components analysis to create the DHS household wealth index. In the initial survey, the wealth index was created by allocating household scores and then ranking each member of the household population according to their score. The distribution was then split into five equal groups, each with 20% of the population, using economic indicators like the standard of the housing, the amenities provided in the home, the size of the consumer goods market, and the size of the land holding. Following that, this study kept the wealth index from the original survey’s five groups (lowest, second, middle, fourth, highest).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

We took into account sampling weights, stratification, and clustering using the Stata survey module (‘svy’). Calculations were made to determine the prevalence rate. In order to ascertain the heterogeneity of the prevalence of overweight and obesity among women of reproductive age in SSA, forest plot analysis was used. A forest plot is required in an observational study to synthesize data. When dealing with descriptive data or graphically displaying summary statistics such as prevalence, Stata has no limitations. In addition, in the forest plot, we calculated each weighted effect size (w*es). This is calculated by multiplying the size of each effect by the study weight. The Q test, which works similarly to the t test, measures country heterogeneity. It was calculated as the weighted sum of squared differences between individual study effects and the overall study effect. We rejected the null hypothesis at p < 0.05 (and hence the countries’ estimates are not similar). Statistical significance was determined at 5%. Stata 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) was used.

2.4. Ethical Consideration

The population-based datasets used in this study were in the public domain and were freely accessible online without any identifying information. DHS/ICF International approved the authors’ request to use the information. For the protection of respondents’ privacy, the DHS program adheres to industry standards. The survey will adhere to the Human Subjects Protection Act as set forth by the US Department of Health and Human Services according to ICF International. Prior to conducting the surveys, the DHS team sought and received ethical approval from each country’s National Health Research Ethics Committee. This study did not require any additional approvals. Further information on data and ethical standard can be found here: http://goo.gl/ny8T6X (accessed on 10 July 2022).

3. Results

Table S1 shows the descriptive statistics for respondents based on demographic characteristics such as age (years), place of residence, education, household wealth quintile and marital status. According to the findings, there were more women in the lower age (15–19, 20–24, and 25–29 years) in the survey across countries. Furthermore, except for Angola, Cameroon, Congo, Cote d’Ivoire, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Liberia, Mauritania, Namibia, Sao Tome and Principe and South Africa, countries had higher proportions of respondents from rural settlements. In many countries, the majority of respondents had no formal education or only a primary education, and they belonged to the lowest and second wealth quintiles. Table S1 is available as a Supplementary File.

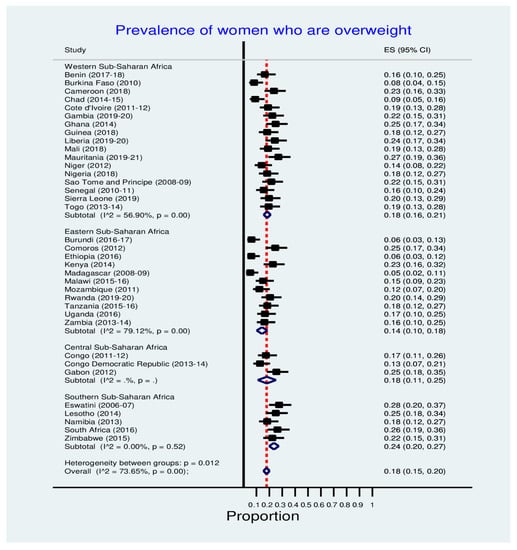

Figure 2 shows inequalities in overweight prevalence among women of reproductive age in sub-Saharan countries. Clearly, Eswatini (28%), Mauritania (27%), South Africa (26%), Gabon, Lesotho and Ghana (25% each) had the highest overweight prevalences.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of overweight among women in SSA countries.

Table 1 shows the prevalence of overweight among women of reproductive age in SSA countries across the women’s characteristics. Prominently, the prevalence of overweight was higher among older women, those from an urban place of residence, women who had secondary/higher education and the richest household wealth quintiles.

Table 1.

Distribution of overweight among women in SSA countries.

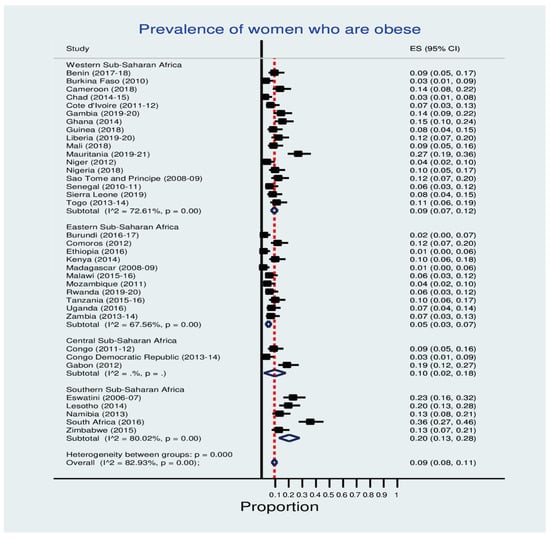

Figure 3 depicts the obesity prevalence disparities among women of reproductive age in sub-Saharan African countries. Obesity prevalence was highest in South Africa (36%), Mauritania (27%), Eswatini (23%), Lesotho (20%), Gabon (19%) and Ghana (15%).

Figure 3.

Prevalence of obesity among women in SSA countries.

Table 2 shows the prevalence of obesity among women of reproductive age in sub-Saharan African countries, broken down by the women’s characteristics. Obesity was more prevalent among older women, those living in urban areas, women with secondary/higher education and those in the richest household wealth quintiles.

Table 2.

Distribution of obesity among SSA countries women.

4. Discussion

The current study examined the prevalence and sociodemographic factors that are associated with overweight and obesity in women of reproductive age in SSA countries. The prevalence of obesity was found to be much higher in some countries than others. Many studies have evaluated the progress of several intervention programs put in place by home countries and their international partners to minimize the impacts of obesity among the African population, especially the youths and women. It is assumed that the major cause of obesity is physical inactivity as well as over-nutrition. Most African countries have witnessed high prevalence of overweight and obesity among their female populations. Overweight and obesity were once only associated with developed countries; however, as a result of urbanization, changes in lifestyle and environmental factors [21], the prevalence is increasing in low- and middle-income countries, including those in Africa [22]. Obesity and overweight, which are both major risk factors for many chronic noncommunicable diseases, were shown to be highly prevalent among our sub-Saharan African studied population.

These facts have contributed immensely to enormous challenges in African public health sectors. The emergence of obesity and overweight in developing countries has been reported by many authors [23,24,25]. Their studies have provided an overall picture of obesity epidemic in developing countries such as Africa. Yet deep analysis to decipher the principles of its occurrence in some specific sociodemographic regions and socioeconomic classes has not yet take place. Moreover, some of these studies could not compare the phenomenon of obesity across sociodemographic regions, and this could have been the result of the sources of data and methodologies employed in those studies. These studies therefore gave us the motivations to not only to build on their findings but fill gaps needed to understand the impacts of obesity pm the population. This study, therefore, analyzed a large dataset retrieved from the most recent National Demographic and Health Surveys from women of reproductive age from the studied sub-Saharan African nations to investigate the prevalence of overweight and obesity in the region and the socioeconomics well as the sociodemographic disparities in obesity and overweight among the women populations in the region.

This study also discovered that a woman’s socioeconomic status (wealth and education) influences obesity prevalence. Women from lower-income families and those with no formal education or only a primary education were less likely to be obese than women from higher-income families and those with secondary and higher education levels. Obesity was more prevalent in the highest income group than in the lowest income group. Obesity and overweight were also found to be more prevalent among the most educated women when compared with those with the least education. This difference in the relationship between obesity and income and obesity and education contradicts the findings of other studies conducted in the United States [26,27] and Germany [28]. Whereas these studies reported a decrease in the prevalence of obesity in the studied populations with increase in the educational attainment and income, we observed the contrary in our study. In our study, poor household wealth status may limit families’ access to luxury lifestyles, which may include eating habits as well as having time to relax and many other aspects of life. in Africa, low-income earners toil every day of the week to earn a basic living [24,29].

The long hours of hard labor they subject themselves on daily basis burn any extra calories they may store in their bodies. This is unlike the high-income earners and highest educated who may spend long hours in air-conditioned offices in skyscrapers, eat more junk foods (due to the fact that they often had to work on their computers), go for long meetings and have little or no time for exercise. Such lifestyles have been established to be risk factors for overweight and obesity. Workplaces have also been shown to contribute to the obesity epidemic. Shift work, job stress and long work hours are examples of “obesogenic” work environment factors [30]. Doctors, nurses and pharmacists are among the most important groups of workers confronted with such obesogenic work environments. Teachers’ work environments also encourage sedentary behavior, and a high prevalence of obesity has been reported among them [31]. Furthermore, lower-educated women are less likely to obtain jobs that will make them sit for long hours in a particular place. Because they engage themselves in hard labor to make their living, there is high tendency to burn up extra calories and fats. We therefore can say that women’s socioeconomic status is a risk factor for overweight and obesity.

Our study found that age was significantly associated with obesity as women who were 35–49 years had the highest prevalence of obesity, in contrast with those who were less than 25 years and 25–34 years. A study conducted among women in Nigeria and South Africa [21] also reported age as a risk factor for obesity. Previous research has linked aging to increased adiposity in white adipose tissue as well as thermogenic impairment in brown adipose tissue, which may increase the prevalence of obesity [32]. Furthermore, estrogen receptor (ER) has been shown in females to play a protective role in maintaining metabolic homeostasis [33]. Previous research has found an inverse relationship between age and gene expression of ER and the ratio of ER to ER in female abdominal subcutaneous fatty tissue [34]. According to some studies, the prevalence of obesity varies not only by age but also by income and education level [26,35]. In our study, participants who were unemployed had a higher likelihood of being obese than participants who were employed. We also discovered that women with a high school or higher education had a lower likelihood of central obesity than women with primary school or less education. This might be a result of cognitive and health literacy differences between education levels. For the purpose of promoting the health of reproductive-aged women, more research is required to elucidate the precise mechanisms linking the pertinent variables and central obesity in this population group.

In addition, we observed that overweight and obesity among the women across the studied African countries had a higher prevalence among urban-dwelling women than rural women. All of the SSA countries under study were predicted to see a decrease in the prevalence of overweight and obesity. Our results confirm the high prevalence of over-nutrition for these countries that has been documented in the literature. The urban–rural differences reported in some SSA studies are supported by the variations in BMI status by location [21,36,37]. We discovered that participants in our urban settings were more likely to be obese or overweight than their rural counterparts. This supports previous research that found a link between urbanization and higher BMI both within and between countries. In a study conducted in Tanzania, the prevalence of obesity among urban women was 36%, compared with 6% among rural women [38,39]. In Uganda, the prevalence of overweight was 15.8% in rural adults and 23.8% in peri-urban adults, while obesity prevalence among rural and peri-urban adults was 3.9% and 17.8%, respectively. [40]. A study in Nigeria found that 40% and 30% of females in urban and rural Nigeria were overweight or obese, respectively [41]. These dietary differences between urban and rural areas have been linked to a shift away from traditional diets toward processed, energy-dense foods, fat, foods derived from animals, sugar and sweetened beverages [41]. Because of higher incomes and the greater availability of processed foods, this dietary shift may be more pronounced among urban residents than among rural residents. Despite the fact that our findings apply to all of the countries studied, there are differences in prevalence levels across the board. We believe that this regional disparity is related to the respective countries’ levels of economic development and urbanization [42,43].

When compared with previous studies and with socio-economic status, rural–urban, geographical and age differences, we discovered that the prevalence of overweight and obesity is increasing in our study countries. This has significant implications for these countries’ and the region’s health care systems, as they will face increased demand for care of chronic conditions related to obesity and overweight, such as osteoarthritis, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases and cancers. Diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular diseases are already among the topmost killers in sub-Saharan African countries [44,45]. The prevalence of obesity and overweight among urban residents and women emphasizes the need for targeted or group-specific interventions to combat the epidemic. The development of interventions for the control of over-nutrition should target the barriers to lifestyle change at the individual, environmental and socioeconomic levels, with input from stakeholders at different levels. It is important to develop and put into practice policies that control dietary practices and foster environments that promote physical activity such as sidewalks and walkways and that support health services.

Strengths and Limitations

Large national datasets were examined for plausible comparisons for this study. A significant advantage is the ability to combine many countries. However, we used a cross-sectional study to collect data from various countries at various points in time, and potential factors influencing each country’s socioeconomic and feeding condition might have been linked to the study’s outcome variables. These factors include the political situation, the development of health care facilities and the health policy of the government. This could lead to sampling, overweight and obesity estimate bias. A traditional measure of wealth is household spending, which is not collected by the DHS. The asset-based wealth index used here is merely a surrogate for household economic well-being, and its findings are not always in line with measures of revenue and expenditure in cases where such statistics are readily accessible or can be collected with reliability.

5. Conclusions

Some SSA countries had high rates of overweight and obesity. Women who are older, live in urban areas, are educated and come from wealthy backgrounds were found to be more vulnerable. Additionally, our study discovered that urbanization—a proxy for city living—is a significant predictor of overweight and obesity. The need to address the rising incidence of obesity in SSA grows more urgent as urbanization and the accompanying nutrition transition continue. This high prevalence is correlated with the reported rising non-communicable disease prevalence in the area, underscoring the urgent need for action. It is imperative to spread awareness about the importance of lifestyle changes in preventing obesity and the associated health risks among urban residents, professionals and women. We also advise these countries to implement routine biometrics.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/women2040029/s1, Table S1: Descriptive statistics results for reproductive-aged women in SSA countries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.U.O., O.C.O., C.I.N. and M.E.; Data c uration, M.E.; Formal analysis, M.E.; Investigation, O.U.O., O.C.O., C.I.N. and M.E.; Methodology, M.E.; Project administration, O.U.O., O.C.O., C.I.N. and M.E.; Resources, M.E; Software, M.E.; Supervision, M.E.; Validation, M.E.; Visualization, M.E.; Writing—original draft, O.U.O., O.C.O., C.I.N. and M.E.; Writing–review & editing, O.U.O., O.C.O., C.I.N. and M.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Inner City Fund (ICF) provided technical assistance throughout the survey program with funds from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). However, there was no funding or sponsorship for this study or the publication of this article. This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approval was not required for this study because the authors used secondary data that were freely available in the public domain. As a result, IRB approval was not required for this study. More information about DHS data and ethical standards can be found at: http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm (accessed on 15 June 2022).

Statement of Informed Consent: The Demographic and Health Survey is an open-source dataset that has been de-identified. As a result, the consent for publication requirement is null and void.

Data Availability Statement

Data for this study were obtained from the National Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) of the studied African countries, which can be found at http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm (accessed on 15 June 2022).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the MEASURE DHS project for granting permission to use and access to the original data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors state that the research was carried out in the absence of any commercial or financial partnerships or connections that could be interpreted as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Amegbor, P.M.; Yankey, O.; Davies, M.; Sabel, C.E. Individual and contextual predictors of overweight or obesity among women in Uganda: A spatio-temporal perspective. GeoJournal 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Obesity and Overweight—Key Facts. 2018. Available online: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 26 November 2018).

- Nglazi, M.D.; Ataguba, J.E.-O. Overweight and obesity in non-pregnant women of childbearing age in South Africa: Subgroup regression analyses of survey data from 1998 to 2017. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amugsi, D.A.; Dimbuene, Z.T.; Mberu, B.; Muthuri, S.; Ezeh, A.C. Prevalence and time trends in overweight and obesity among urban women: An analysis of demographic and health surveys data from 24 African countries, 1991–2014. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e017344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2019, 396, 1223–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addae, H.Y.; Tahiru, R.; Azupogo, F. Factors associated with overweight or obesity among post-partum women in the Tamale Metropolis, Northern Ghana: A cross-sectional study. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2022, 41, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bantie, G.M.; Aynie, A.A.; Assefa, M.K.; Kasa, A.S.; Kassa, T.B.; Tsegaye, G.W. Knowledge and attitude of reproductive age group (15-49) women towards Ethiopian current abortion law and associated factors in Bahir Dar city, Ethiopia. BMC Women’s Health 2020, 20, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neupane, S.; Prakash, K.C.; Doku, D.T. Overweight and obesity among women: Analysis of demographic and health survey data from 32 Sub-Saharan African Countries. BMC Public Health 2015, 16, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukora-Mutseyekwa, F.; Zeeb, H.; Nengomasha, L.; Adjei, N.K. Trends in Prevalence and Related Risk Factors of Overweight and Obesity among Women of Reproductive Age in Zimbabwe, 2005–2015. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiwani, S.S.; Gatica-Domínguez, G.; Crochemore-Silva, I.; Maïga, A.; Walton, S.; Hazel, E.; Baille, B.; Bose, S.; Bosu, W.K.; Busia, K.; et al. Trends and inequalities in the nutritional status of adolescent girls and adult women in sub-Saharan Africa since 2000: A cross-sectional series study. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amugsi, D.A.; Dimbuene, Z.T.; Kyobutungi, C. Correlates of the double burden of malnutrition among women: An analysis of cross sectional survey data from sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dake, F.A.; O Tawiah, E.; Badasu, D.M. Sociodemographic correlates of obesity among Ghanaian women. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 14, 1285–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidu, A.-A.; Ahinkorah, B.O.; Agbaglo, E.; Nyaaba, A.A. Overweight and obesity among women of reproductive age in Mali: What are the determinants? Int. Health 2020, 13, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moise, I.K.; Kangmennaang, J.; Halwiindi, H.; Grigsby-Toussaint, D.S.; Fuller, D.O. Increase in Obesity Among Women of Reproductive Age in Zambia, 2002–2014. J. Women’s Health 2019, 28, 1679–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mndala, L.; Kudale, A. Distribution and social determinants of overweight and obesity: A cross-sectional study of non-pregnant adult women from the Malawi Demographic and Health Survey (2015–2016). Epidemiol. Health 2019, 41, e2019039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashan, M.R.; Haider, S.S.; Pial, R.H.; Hossain, A.; E-Elahee, M.; Das Gupta, R. Association between television viewing frequency and overweight/obesity among reproductive age women: Cross-sectional evidence from South Africa Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Obes. Med. 2021, 25, 100362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahratian, A. Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity Among Women of Childbearing Age: Results from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Matern. Child Health J. 2008, 13, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corsi, D.J.; Neuman, M.; Finlay, J.E.; Subramanian, S.V. Demographic and health surveys: A profile. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 41, 1602–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoran, S.D.; Xue, X.Z.; Wesseh, P.K. Signatures of water resources consumption on sustainable economic growth in Sub-Saharan African countries. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2016, 5, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutstein, S.O.; Staveteig, S. Making the Demographic and Health Surveys Wealth Index Comparable; DHS Methodological Reports No. 9; ICF International: Rockville, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ajayi, I.O.; Adebamowo, C.; Adami, H.-O.; Dalal, S.; Diamond, M.B.; Bajunirwe, F.; Guwatudde, D.; Njelekela, M.; Nankya-Mutyoba, J.; Chiwanga, F.S.; et al. Urban–rural and geographic differences in overweight and obesity in four sub-Saharan African adult populations: A multi-country cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finucane, M.M.; Stevens, G.A.; Cowan, M.J.; Danaei, G.; Lin, J.K.; Paciorek, C.J.; Singh, G.M.; Gutierrez, H.R.; Lu, Y.; Bahalim, A.N.; et al. National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: Systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9.1 million participants. Lancet 2011, 377, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, T.; Yang, W.; Chen, C.-S.; Reynolds, K.; He, J. Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 1431–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, S.; Perkins, J.M.; Özaltin, E.; Smith, G.D. Weight of nations: A socioeconomic analysis of women in low- to middle-income countries. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 93, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, M.; Fleming, T.; Robinson, M.; Thomson, B.; Graetz, N.; Margono, C.; Mullany, E.C.; Biryukov, S.; Abbafati, C.; Abera, S.F.; et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014, 384, 766–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, C.L.; Fakhouri, T.H.; Carroll, M.D.; Hales, C.; Fryar, C.D.; Li, X.; Freedman, D.S. Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults, by Household Income and Education—United States, 2011–2014. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2017, 66, 1369–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, C.L.; Lamb, M.M.; Carroll, M.D.; Flegal, K.M. Obesity and socioeconomic status in adults: United States, 2005-2008. NCHS Data Brief 2010, 50, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lamerz, A.; Kuepper-Nybelen, J.; Wehle, C.; Bruning, N.; Trost-Brinkhues, G.; Brenner, H.; Hebebrand, J.; Herpertz-Dahlmann, B. Social class, parental education, and obesity prevalence in a study of six-year-old children in Germany. Int. J. Obes. 2005, 29, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adepoju, P. Key to Addressing Obesity in Africa Lies in Education, Food Systems. Devex [Internet]. 2021. Available online: https://www.devex.com/news/sponsored/key-to-addressing-obesity-in-africa-lies-in-education-food-systems-99644 (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Buss, J. Associations between Obesity and Stress and Shift Work among Nurses. Work. Health Saf. 2012, 60, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pobee, R.; Owusu, W.; Plahar, W. The prevalence of obesity among female teachers of child-bearing age in Ghana. Afr. J. FOOD, Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2013, 13, 7820–7839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Saha, P.K.; Ma, X.; Henshaw, I.O.; Shao, L.; Chang, B.H.J.; Buras, E.D.; Tong, Q.; Chan, L.; McGuinness, O.P.; et al. Ablation of ghrelin receptor reduces adiposity and improves insulin sensitivity during aging by regulating fat metabolism in white and brown adipose tissues. Aging Cell 2011, 10, 996–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevener, A.L.; Clegg, D.J.; Mauvais-Jarvis, F. Impaired estrogen receptor action in the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2015, 418, 306–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-M.; Erickson, C.; Bessesen, D.; Van Pelt, R.E.; Cox-York, K. Age- and menopause-related differences in subcutaneous adipose tissue estrogen receptor mRNA expression. Steroids 2017, 121, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.-J. The long-run effect of education on obesity in the US. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2016, 21, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwokorie, C.U. Prevalence, risk factors and awareness of hypertension in semi-urban and rural communities in Nigeria—A systematic review. J. Biotechnol. Sci. Res. 2014. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Prevalence%2C-risk-factors-and-awareness-of-in-and-in-Nwokorie/ce478a7641d2f5c4f7ceddcbac644aaec80f9428 (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- A Njelekela, M.; Mpembeni, R.; Muhihi, A.; Mligiliche, N.L.; Spiegelman, D.; Hertzmark, E.; Liu, E.; Finkelstein, J.L.; Fawzi, W.W.; Willett, W.C.; et al. Gender-related differences in the prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors and their correlates in urban Tanzania. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2009, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhihi, A.J.; Njelekela, M.A.; Mpembeni, R.; Mwiru, R.S.; Mligiliche, N.; Mtabaji, J. Obesity, Overweight, and Perceptions about Body Weight among Middle-Aged Adults in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. ISRN Obes. 2012, 2012, e368520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njelekela, M.; Kuga, S.; Nara, Y.; Ntogwisangu, J.; Masesa, Z.; Mashalla, Y.; Ikeda, K.; Mtabaji, J.; Yamori, Y.; Tsuda, K. Prevalence of Obesity and Dyslipidemia in Middle-Aged Men and Women in Tanzania, Africa: Relationship with Resting Energy Expenditure and Dietary Factors. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2002, 48, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kirunda, B.E.; Fadnes, L.T.; Wamani, H.; Broeck, J.V.D.; Tylleskär, T. Population-based survey of overweight and obesity and the associated factors in peri-urban and rural Eastern Uganda. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Kayode, J.; O Olayinka, A.; O Sola, A.; O Steven, A. Underweight, overweight and obesity in adults Nigerians living in rural and urban communities of Benue State. Ann. Afr. Med. 2011, 10, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziraba, A.K.; Fotso, J.C.; Ochako, R. Overweight and obesity in urban Africa: A problem of the rich or the poor? BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Shayo, G.; Mugusi, F.M. Prevalence of obesity and associated risk factors among adults in Kinondoni municipal district, Dar es Salaam Tanzania. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, T.; Allen, C.; Arora, M.; Barber, R.M.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Brown, A.; Liang, X.; Kawashima, T.; Coggeshall, M.; et al.; Global Burden of Disease Study Collaborators 2013 Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015, 386, 743–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1789–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).