Trends in Hospitalization and Mortality from Cervical Cancer in Brazil Are Linked to Socioeconomic and Care Indicators

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

- (a)

- We selected separately the code (C53), within the item called category in the ICD-10;

- (b)

- Deaths related to the code were stratified according to the variables: age group (ranging from 25 to 64 years old, divided into 5-year age groups); location (administrative regions); and year (2010 to 2015).

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CC | Cervical cancer |

| SIM | Information System Mortality |

| DATASUS | Data from the Department of Informatics of the Unified Health System |

| ICD | International Classification of Diseases |

| IBGE | Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics |

| SIH | Hospital Information System (SIH), Hospital Inpatient Authorization |

References

- Prowse, M. Towards a Clearer Understanding of ’Vulnerability’ in Relation to Chronic Poverty. 2003. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1754445 (accessed on 6 April 2022).

- Costa, M.A.; dos Santos, M.P.G.; Marguti, B.; Pirani, N.; Pinto, C.V.d.S.; Curi, R.L.C.; Ribeiro, C.C.; de Albuquerque, C.G. Vulnerabilidade Social no Brasil: Conceitos, Métodos e Primeiros Resultados para Municípios e Regiões Metropolitanas Brasileiras; Texto para Discussão; Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (IPEA): Brasília, Brazil, 2018.

- Ayres, J.R.C.M.; França Júnior, I.; Calazans, G.J.; Saletti Filho, H.C. O conceito de vulnerabilidade e as práticas de saúde: Novas perspectivas e desafios. In Promoção da Saúde: Conceitos, Reflexões, Tendências; Czeresnia, D., Freitas, C.M., Eds.; Fiocruz: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Palma, A.; Mattos, U.A.D.O. Contribuições da ciência pós-normal à saúde pública e a questão da vulnerabilidade social Contribution of post-normal science to public health and the issue of social vulnerability. História 2001, 8, 567–590. [Google Scholar]

- De Souza Kock, K.; Righetto, A.; de Oliveira Machado, M. Vulnerabilidade social feminina e mortalidade por neoplasias da mama e colo do útero no Brasil. Rev. Saúde Ciência 2020, 9, 64–77. [Google Scholar]

- Tavares, T.R.P.; de Andrade, F.B.; Dantas, D.K.F.; Ludovico, M.R.d.; de Araújo, D.V. Avaliação de indicadores para câncer de mama no período de 2009 a 2013. Rev. Ciênc Plural. 2016, 2, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchetti, J.C.; Traldi, M.C.; Da Fonseca, M.R.C.C. Vulnerabilidade social e autocuidado relacionado à prevenção do câncer de mama e de colo uterino. Rev. Família Ciclos de Vida e Saúde no Contexto Soc. 2016, 4, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccarella, S.; Lortet-Tieulent, J.; Plummer, M.; Franceschi, S.; Bray, F. Worldwide trends in cervical cancer incidence: Impact of screening against changes in disease risk factors. Eur. J. Cancer 2013, 49, 3262–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instituto Nacional do Câncer (INCA). Estimativa 2014: Incidência de Câncer no Brasil; INCA: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pfaendler, K.S.; Wenzel, L.; Mechanic, M.B.; Penner, K.R. Cervical cancer survivorship: Long-term quality of life and social support. Clin. Ther. 2015, 37, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SEADE—Fundação Sistema Estadual de Análise de Dados. Índice Paulista de Vulnerabilidade Social; SEADE: São Paulo, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Waskul, D.D.; Van Der Riet, P. The abject embodiment of cancer patients: Dignity, selfhood and the grotesque body. Symbolic Interaction. Symb. Interact. 2002, 25, 487–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrossi, S.; Matos, E.; Zengarini, N.; Roth, B.; Sankaranayananan, R.; Parkin, M. The socio economic impact of cervical cancer on patients and their families in Argentina and its influence on radiotherapy compliance Results from a cross sectional study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2007, 105, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, A.J.; Ndom, P.; Atenguena, E.; Nouemssi, J.P.M.; Ryder, R.W. Cancer care challenge in developing countries. Cancer 2011, 118, 3627–3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittet, S.; Goltz, S.; Cody, A. Progress in Cervical Cancer Prevention: The CCA Report Card 2015; Cervical Cancer Action: Seattle, WA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Marguti, B.O.; Costa, M.A.; Pinto, C.V.d.S. Territórios em Números: Insumos para Políticas Públicas a Partir da Análise do IDHM e do IVS de Municípios e Unidades da Federação Brasileira, Livro 1; IPEA: Brasília, Brasil, 2017; 340p. [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa-Muñoz, R.L.; Formiga, M.Y.Q.; Silva, A.E.V.F.; de Lima Silva, M.B.; Vieira, R.C.; Galdino, M.M.; de Morais, M.T.M. Hospitalizações por neoplasias em idosos no âmbito do Sistema Único de Saúde na Paraíba, Brasil. Saúde e Pesqui 2015, 8, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, O.B.; Boschi-Pinto, C.; Lopez, A.D.; Murray, C.J.; Lozano, R.; Inoue, M. Age Standardization of Rates: A New WHO Standard; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001; Volume 9, p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, M.A.; Marguti, B.O.E. (Eds.) Atlas da Vulnerabilidade Social Nos Municípios Brasileiros. 2015. Available online: http://ivs.ipea.gov.br/images/publicacoes/Ivs/publicacao_atlas_ivs.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Rosa, W. Sexo e cor/raça como categorias de controle social: Uma abordagem sobre desigualdades socioeconômicas a partir de dados do Retrato das Desigualdades de Gênero e Raça—Terceira edição. In Faces da Desigualdade de Gênero e Raça no Brasil; Bonetti, A., ABREU, M.A., Eds.; Ipea: Brasília, Brazil, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Girianelli, V.R.; Gamarra, C.J.; Azevedo, E.; Silva, G. Os grandes contrastes na mortalidade por câncer do colo uterino e de mama no Brasil. Rev. Saude Publica 2014, 48, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Fonseca, A.J.; Ferreira, L.P.; Dalla-Benetta, A.C.; Roldan, C.N.; Ferreira, M.L.S. Epidemiologia e impacto econômico do câncer de colo de útero no Estado de Roraima&58; a perspectiva do SUS Epidemiology and economic impact of cervical cancer in Roraima, a Northern state of Brazil&58; the public health system perspective. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obs. 2010, 32, 386–392. [Google Scholar]

- Correa, P. The war against cervical cancer in Latin America and the Caribbean. Triumph of the scientists. Challenge for the community. Vaccine 2008, 26 (Suppl. 11), iii–iv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, L.V.D.A.; Maciel, E.D.S.; Paiva, L.D.S.; Alcantara, S.D.S.A.; Nascimento, V.B.D.; Fonseca, F.L.A.; Adami, F. Inequalities in Mortality and Access to Hospital Care for Cervical Cancer—An Ecological Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, G.M.S.; Barbosa, D.P.; Megale, E.Z.; da Silva, E.K.F.; Santos, E.A.; do Nascimento Florêncio, C. Conhecimento sobre a vacinação contra o HPV em estudantes de medicina no Rio de Janeiro. Rev. Sustinere 2018, 6, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allin, S.; Masseria, C.; Mossialos, E. Measuring socioeconomic differences in use of health care services by wealth versus by income. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 1849–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buron, A.; Auge, J.M.; Sala, M.; Roman, M.; Castells, A.; Macià, F.; Comas, M.; Guiriguet, C.; Bessa, X.; Castells, X.; et al. Association between socioeconomic deprivation and colorectal cancer screening outcomes: Low uptake rates among the most and least deprived people. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179864. [Google Scholar]

- Morère, J.-F.; Eisinger, F.; Touboul, C.; Lhomel, C.; Couraud, S.; Viguier, J. Decline in cancer screening in vulnerable populations? Results of the EDIFICE surveys. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 20, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.K.; Miller, B.A.; Hankey, B.F.; Edwards, B.K. Persistent area socioeconomic disparities in US incidence of cervical cancer, mortality, stage, and survival, 1975–2000. Cancer 2004, 101, 1051–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPEA—Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada. In Atlas da Vulnerabilidade Social nas Regiões Metropolitanas Brasileiras; Ipea: Brasília, Brazil, 2015.

| Brazil/Regions | Age-Standardized Incidence * (95% CI) of Hospital Admissions for Cervical Cancer † (×10,000 Inhabitants) | Linear Regression Admissions | |||||||

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | β | p | r2 | |

| North | 1.57 (1.56; 1.57) | 1.58 (1.57; 1.58) | 1.56 (1.55; 1.56) | 1.56 (1.55; 1.56) | 1.38 (1.37; 1.38) | 1.39 (1.38; 1.39) | −0.04 | 0.032 | 0.65 |

| Northeast | 2.10 (2.09; 2.11) | 2.02 (2.01; 2.03) | 1.99 (1.98; 1.99) | 1.99 (1.98; 1.99) | 1.76 (1.75; 1.77) | 1.67 (1.66; 1.67) | −0.08 | 0.006 | 0.84 |

| Southeast | 1.70 (1.69; 1.70) | 1.49 (1.48; 1.50) | 1.53 (1.52; 1.54) | 1.43 (1.42; 1.43) | 1.32 (1.31; 1.33) | 1.33 (1.32; 1.34) | −0.07 | 0.007 | 0.83 |

| South | 2.83 (2.82; 2.83) | 2.62 (2.61; 2.62) | 2.43 (2.42; 2.43) | 2.21 (2.20; 2.21) | 2.01 (2.00; 2.01) | 1.94 (1.93; 1.94) | −0.18 | <0.001 | 0.98 |

| Central-West | 2.28 (2.27; 2.28) | 1.99 (1.98; 2.00) | 1.87 (1.87; 1.88) | 1.63 (1.62; 1.63) | 1.44 (1.44; 1.44) | 1.43 (1.42; 1.43) | −0.17 | 0.001 | 0.94 |

| Brazil | 2.00 (1.99; 2.01) | 1.84 (1.84; 1.84) | 1.81 (1.80; 1.82) | 1.71 (1.70; 1.71) | 1.55 (1.54; 1.56) | 1.51 (1.50; 1.51) | −0.09 | <0.001 | 0.95 |

| Brazil/Regions | Age-Standardized Mortality * (95% CI) from Cervical Cancer † (×10,000 inhabitants) | Linear Regression Mortality | |||||||

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Β | p | r2 | |

| North | 0.71 (0.70; 0.71) | 0.70 (0,69; 0.71) | 0.72 (0.71; 0.73) | 0.78 (0.77; 0.79) | 0.77 (0.76; 0.78) | 0.75 (0.74; 0.75) | 0.012 | 0.076 | 0.48 |

| Northeast | 0.40 (0.39; 0.41) | 0.41 (0.40; 0.42) | 0.43 (0.42; 0.43) | 0.41 (0.40; 0.41) | 0.43 (0.42; 0.43) | 0.41 (0.40; 0.42) | 0.002 | 0.455 | 0.06 |

| Southeast | 0.27 (0.26; 0.27) | 0.26 (0.25; 0.27) | 0.24 (0.23; 0.25) | 0.25 (0.24; 0.25) | 0.24 (0.23; 0.24) | 0.25 (0.24; 0.25) | −0.004 | 0.120 | 0.36 |

| South | 0.31 (0.30; 0.31) | 0.32 (0.31; 0.33) | 0.32 (0.31; 0.32) | 0.32 (0.31; 0.33) | 0.29 (0.28; 0.29) | 0.33 (0.32; 0.33) | −0.001 | 0.875 | 0.01 |

| Central-West | 0.42 (0.41; 0.42) | 0.36 (0.35; 0.38) | 0.36 (0.35; 0.36) | 0.36 (0.36; 0.37) | 0.38 (0.37; 0.38) | 0.41 (0.40; 0.41) | 0.001 | 0.958 | 0.01 |

| Brazil | 0.34 (0.33; 0.34) | 0.34 (0.33; 0.35) | 0.34 (0.33; 0.34) | 0.34 (0.34; 0.34) | 0.34 (0.33; 0.34) | 0.35 (0.35; 0.36) | −0.001 | 0.701 | 0.04 |

| Vulnerability Indexes Brazil/Regions | Age-Standardized Incidence * of Hospital Admissions for Cervical Cancer † (×10,000 Inhabitants) | |||||||||||

| Central-West | Northeast | North | Southeast | South | Brazil | |||||||

| rho | p | rho | p | rho | p | rho | p | rho | p | rho | p | |

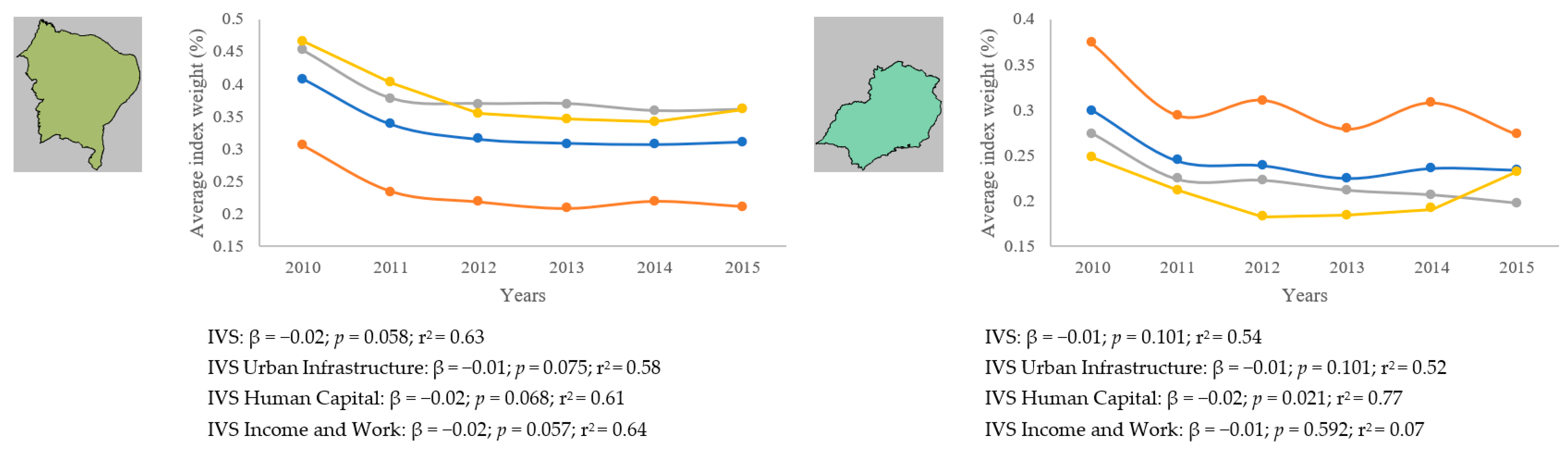

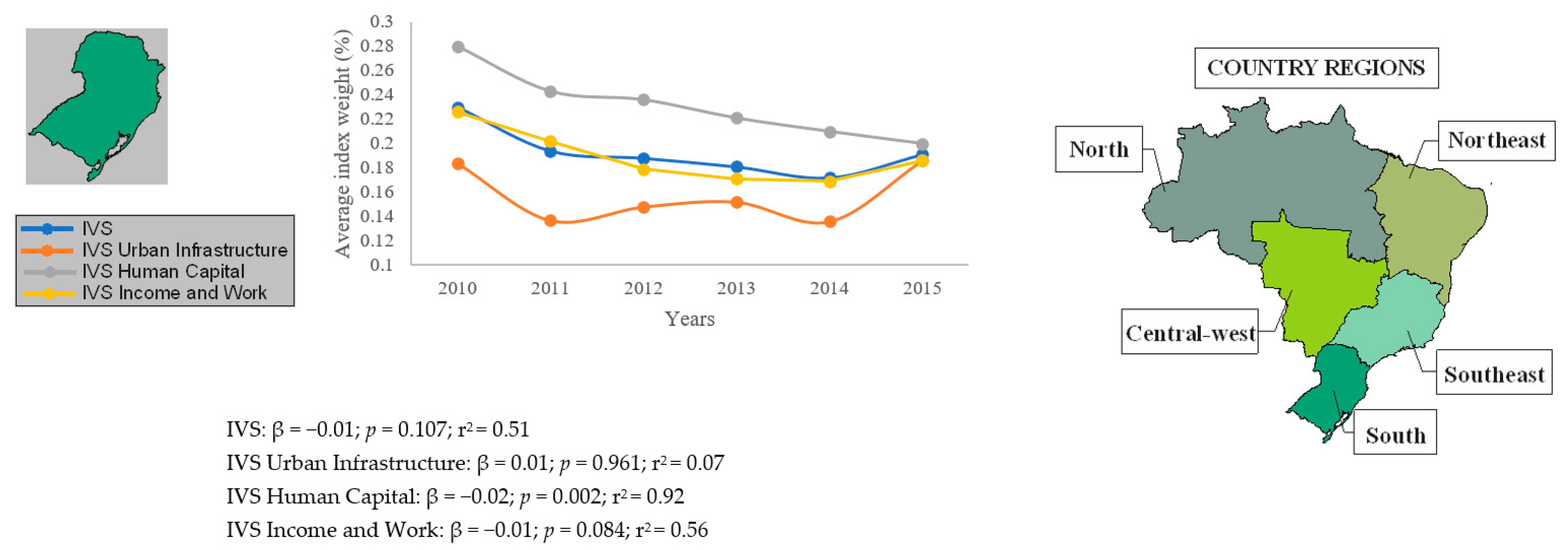

| IVS | 0.82 | 0.041 | 0.62 | 0.181 | 0.61 | 0.202 | 0.83 | 0.039 | 0.78 | 0.065 | 0.80 | 0.057 |

| IVS Urban Infrastructure | 0.75 | 0.084 | 0.58 | 0.223 | 0.64 | 0.174 | 0.81 | 0.046 | 0.07 | 0.891 | 0.79 | 0.061 |

| IVS Human Capital | 0.84 | 0.035 | 0.65 | 0.155 | 0.59 | 0.211 | 0.94 | 0.003 | 0.97 | 0.001 | 0.86 | 0.028 |

| IVS Income and Work | 0.75 | 0.079 | 0.61 | 0.199 | 0.53 | 0.280 | 0.41 | 0.422 | 0.81 | 0.048 | 0.66 | 0.153 |

| Vulnerability Indexes Brazil/Regions | Age-Standardized Mortality * from Cervical Cancer † (×10,000 Inhabitants) | |||||||||||

| Central-West | Northeast | North | Southeast | South | Brazil | |||||||

| rho | p | rho | p | rho | p | rho | p | rho | p | rho | p | |

| IVS | 0.59 | 0.216 | −0.70 | 0.115 | −0.59 | 0.211 | 0.68 | 0.136 | 0.19 | 0.710 | 0.46 | 0.354 |

| IVS Urban Infrastructure | 0.43 | 0.383 | −0.63 | 0.177 | −0.49 | 0.318 | 0.42 | 0.400 | 0.36 | 0.485 | 0.34 | 0.509 |

| IVS Human Capital | 0.46 | 0.347 | −0.69 | 0.125 | −0.62 | 0.184 | 0.68 | 0.131 | 0.04 | 0.952 | 0.37 | 0.481 |

| IVS Income and Work | 0.73 | 0.103 | −0.75 | 0.083 | −0.70 | 0.126 | 0.75 | 0.084 | 0.14 | 0.800 | 0.66 | 0.156 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sousa, L.V.d.A.; Paiva, L.d.S.; Alcantara, S.d.S.A.; Fonseca, F.L.A.; Carvalho, L.E.W.d.; Adami, F. Trends in Hospitalization and Mortality from Cervical Cancer in Brazil Are Linked to Socioeconomic and Care Indicators. Women 2022, 2, 274-284. https://doi.org/10.3390/women2030026

Sousa LVdA, Paiva LdS, Alcantara SdSA, Fonseca FLA, Carvalho LEWd, Adami F. Trends in Hospitalization and Mortality from Cervical Cancer in Brazil Are Linked to Socioeconomic and Care Indicators. Women. 2022; 2(3):274-284. https://doi.org/10.3390/women2030026

Chicago/Turabian StyleSousa, Luiz Vinicius de Alcantara, Laércio da Silva Paiva, Stefanie de Sousa Antunes Alcantara, Fernando Luiz Affonso Fonseca, Luis Eduardo Werneck de Carvalho, and Fernando Adami. 2022. "Trends in Hospitalization and Mortality from Cervical Cancer in Brazil Are Linked to Socioeconomic and Care Indicators" Women 2, no. 3: 274-284. https://doi.org/10.3390/women2030026

APA StyleSousa, L. V. d. A., Paiva, L. d. S., Alcantara, S. d. S. A., Fonseca, F. L. A., Carvalho, L. E. W. d., & Adami, F. (2022). Trends in Hospitalization and Mortality from Cervical Cancer in Brazil Are Linked to Socioeconomic and Care Indicators. Women, 2(3), 274-284. https://doi.org/10.3390/women2030026