Abstract

Participation in microcredit programs has so far received widespread research and policy attention in the context of health and empowerment among Bangladeshi women. However, not much is known regarding the relationship between participation in microcredit programs and healthcare autonomy (HA) among women. In the present study, we analyzed two nationally representative surveys (Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2004 and 2014), to assess the relationships between MC membership and HA among adult women (n = 29163), while adjusting for various sociodemographic correlates. Self-reported healthcare decision-making autonomy was assessed by asking whether or not the participant had final say on her healthcare. The findings revealed that between 2004 (20.9%, 95%CI = 19.8, 22.0) and 2014 (14.1%, 95%CI = 13.3, 15.0), the proportion of women reporting HA decreased significantly, despite considerable improvements across several socioeconomic indices, including higher education enrollment and labor market participation. Between 2004 and 2014, the percentage of microcredit borrowers decreased for Grameen (18.9% vs. 10.7%) and BRAC (7.9% vs. 7.4%), while it increased for BRDB (0.9% vs. 7.0%). A multivariate regression analysis revealed that Grameen Bank membership was positively associated with reporting HA in both male- (OR = 1.16, 95%CI = 1.09, 1.23) and female-headed households (OR = 1.44, 95%CI = 1.13, 1.85). A positive association between microcredit membership and HA was also observed for BRAC (OR = 1.33, 95%CI = 1.20, 1.47) and BRDB (OR = 1.18, 95%CI = 1.09, 1.29), but in the male-headed households only. Further analysis indicated that membership with Grameen bank was the most important predictor of HA, followed by BRAC, BRDB, and ASA, with the degree of importance varying substantially between male- and female-headed households. In conclusion, these findings suggest the potential of microcredit programs to promote healthcare autonomy among Bangladeshi women and provide insights for further research, as to why certain programs are more effective than others.

1. Introduction

Women’s healthcare and human rights issues are growing concerns for achieving the overall sustainable development goals (SDGs) in Bangladesh. During the last two decades, with strong government commitments, combined with the increasing involvement of the microfinance institutions, Bangladesh has been able to make exemplary progress in many areas, such as increasing female school enrollment; labor market participation; and reducing child marriage, domestic violence, and maternal and child mortality rates [1,2,3]. Although the microcredit-based empowerment approaches are not without limitations [4], great hopes are being placed in these programs, to help women enhance their economic freedom and promote autonomy, health, and overall well-being at large. The involvement of several microfinance institutions, especially Grameen [5,6,7,8,9] and BRAC bank [10,11,12,13,14,15], has been well-documented in the development studies and public health literature. To date, not much is known about the contribution of microcredit (MC) programs to women’s HA. This is presumably due, in part, to the underappreciation of the importance of autonomy in the women’s health agenda, and the inherent difficulty in investigating the determinants of HA. In the present study, we addressed this research gap by analyzing cross-sectional data from Bangladesh Demographic and Health Surveys conducted in 2004 and 2014, with the objective of assessing the relationship between MC membership and HA. The surveys collected information regarding women’s membership of the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC), Bangladesh Rural Development Board (BRDB), Association for Social Advancement (ASA), and Grameen Bank, which are the largest microcredit programs operating in the country. While previous studies regarding women’s empowerment in Bangladesh have highlighted the role of microcredit, there has been no systematic study that explored their association, while adjusting for background sociodemographic variables [16,17,18]. Despite criticisms in certain areas [19,20], microcredit programs in Bangladesh have been gaining increasing popularity, owing to their involvement in poverty reduction and rural development initiatives, with a special focus on empowering women through school enrollment and income generation. However, not much is known about their impact on HA among women, which plays a vital role in the overall health and well-being among women and their children. The findings of this study will provide important insights regarding the relative performance of these programs regarding HA, and can help reshape their policies, with the goal of enhancing HA among women.

2. Methods

2.1. Survey and Data Collection

Data for this survey were collected from the Bangladesh DHS surveys conducted in 2004 and 2014, respectively. The surveys were conducted by a private research organization called Mitra and Associates, under the authority of the National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT). Financial support for these surveys was provided by the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and technical assistance by ICF International (Fairfax, VA, USA). The main objectives of the DHS surveys were to provide nationally comparative data on a range of demographic, socioeconomic, and health knowledge-related indicators for generating quality evidence and to assist in evidence-based health policymaking. Sample populations were selected from non-institutional dwellings in both urban and rural areas and included adult men (15–54 years), women (15–49 years), and under-five children (0–59 months). The data used in the present study are based on the women’s questionnaire. The DHS employed multistage sampling techniques that involved the selection of primary sampling units (PSU), also called enumeration areas (EAs), encompassing a certain number of households for further selection. The second step involved a systematic selection of households (on average 30) from each EA, which could vary from survey to survey. In 2004, a total of 11,601 eligible women were selected for interview, of whom 11,440 were finally interviewed (response rate of 98.6%). The number of women interviewed in the 2014 survey was 17,863 finally interviewed (a response rate of 98%). The fieldwork for the two surveys lasted from January to May of 2004 and from June to November 2014, respectively. More details, including questionnaire testing and data collection, were published elsewhere [21,22].

2.2. Measures

The outcome variable was self-reported healthcare decision-making autonomy, which was assessed by the following question: “Do you have final say on your healthcare?” The answering options were: (1) Respondent alone, (2) Jointly by respondent and husband/partner, (3) Husband/partner alone, (4) Someone else, (5) Other. BDHS 2014 used a rephrased version of the question: “Who usually decides on respondent’s health care”, with the same options for answering. In the current literature there exists no universally accepted definition of HA; however, a systematic literature review suggested that most studies define HA in terms of women’s independence in making their own decisions [23]. In light of this, we assumed that both of the single-item questions used in BDHS 2004 and BDHS 2014 fall under the scope of HA.

For the purpose of this study, the answers were collapsed into two categories to indicate HA: “Has autonomy” (respondent alone), and “No autonomy” (jointly by respondent and husband/partner; husband/partner alone; someone else; other). Although joint decision-making is conceptually different from a lack of autonomy in decision-making, we chose to categorize in this manner, based on the understanding that in traditional patriarchal marriages, women are the less dominant partner, which implies that in the event of conflicting spousal decisions, the woman’s choice is unlikely to prevail [24].

The explanatory variable of primary interest was MC membership with the major microfinance institutions, including the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC), Bangladesh Rural Development Board (BRDB), Association for Social Advancement (ASA), and Grameen Bank. In order to measure the independent association between MC membership and HA, we selected several sociodemographic, economic, and media use related variables as potential confounders, given their theoretically relevant association with the outcome and explanatory variables. Both original and review articles were reviewed, to identify the covariates. Based on the review and availability in the BDHS datasets, the following were included in the analysis: Age groups (15–19/20–24/25–29/30–34/35–39/40–44/45–49); Type of locality (Urban/Rural); Education (No/Education/Primary/Secondary/Higher); Occupation (Unemployed/Blue/Collar/White/Collar); Household head’s sex (Male/Female); Wealth quintile (Lowest/Lower/Middle/Higher/Highest) [25].

2.3. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata version 16. Due to missing values, a small proportion (<1%) of the observations were removed, under the assumption that they share similar characteristics with the non-missing observations. Given the clustered structure of the surveys, we used Stata’s svy command for all calculations, to account for sampling weight, strata, and weight. We stratified the analyses by survey year and the sex of the household head, to gain a better understanding of whether household headship plays any role in women’s HA. Analytical methods included descriptive statistics to present the sample profile (reported as percentage with 95%CIs), and multivariate regression techniques to measure the association between MC membership and HA (reported as odds ratios with 95% CIs). In the first step, three sets of binary logistic regression models were run, by adjusting for sociodemographic variables: first for the pooled sample, second for the samples from male-headed households, and third for the samples from female-headed households. The relative importance of the variables were calculated using a machine learning package in R Studio. In order to reconfirm the significance of the findings, we conducted a further analysis, by the stratifying the models by survey year. Additional sensitivity tests were not run, as the series of stratified analyses were deemed sufficient to gauge the robustness of the findings. Level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for all analyses.

Ethical clearance: All participants gave informed consent prior to taking part in the interviews. The study was based on open-access data and therefore is not subject to additional ethical approval.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analyses

In 2004, 21.7% of the women mentioned that they have final say in their healthcare compared to 15.0% in 2014 (Table 1). The percentage of microcredit borrowers decreased for Grameen (18.9% vs. 10.7%) and BRAC (7.9% vs. 7.4%), BRDB (7.0% vs. 0.9%) between 2004 and 2014. In both of the surveys, a greater percentage of the participants were in the age groups between 20 and 29 years, rural residents, and had primary or below primary level education.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (n, %). BDHS 2004 and 2014 [21].

3.2. Multivariate Analyses

As shown in Table 2, Grameen Bank membership was positively associated with reporting HA in both male (OR = 1.16, 95%CI = 1.09, 1.23) and female-headed household (OR = 1.44, 95%CI = 1.13, 1.85). A positive association between microcredit membership and HA was also observed for BRAC (OR = 1.33, 95%CI = 1.20, 1.47) and BRDB (OR = 1.18, 95%CI = 1.09, 1.29), but in the male-headed households only.

Table 2.

Odds ratios of association between microcredit membership and HA among Bangladeshi women.

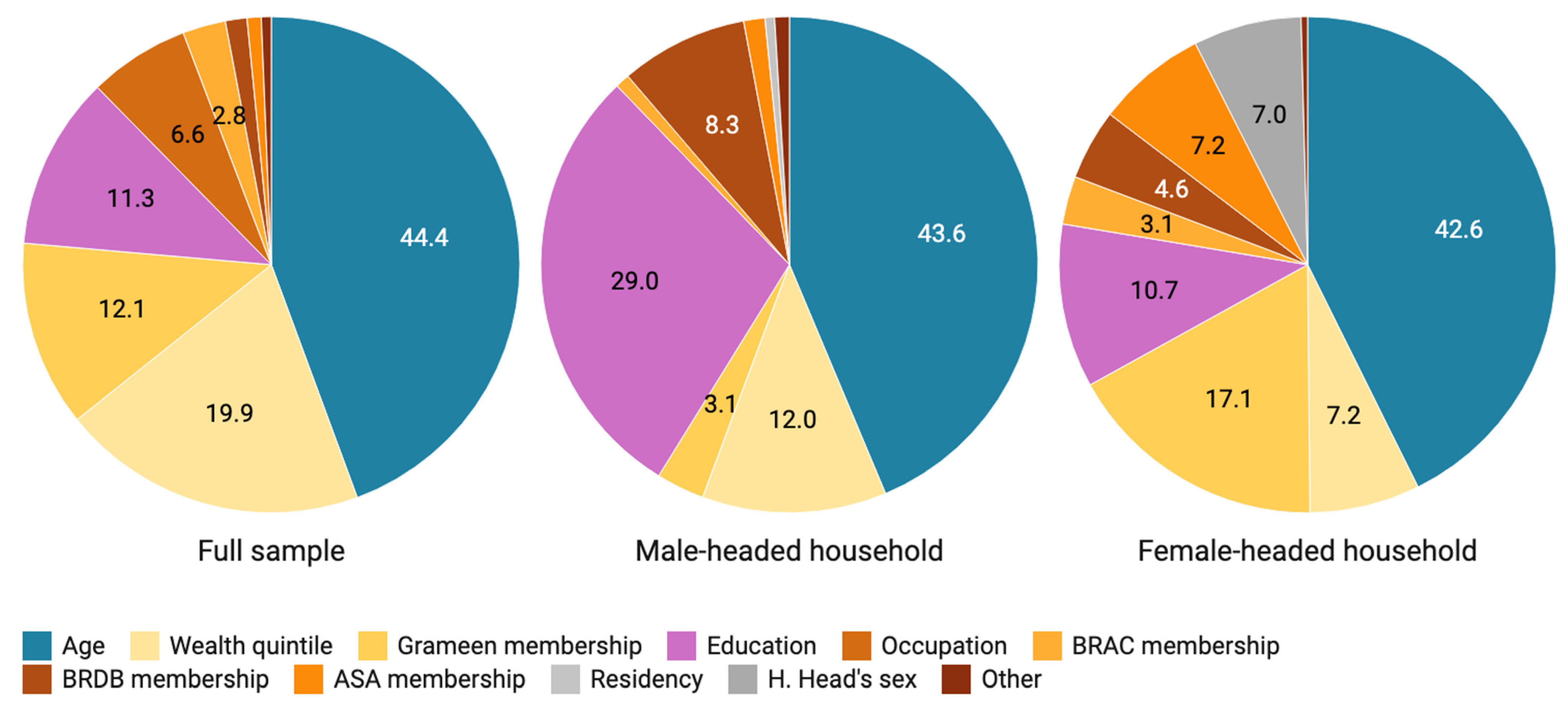

Figure 1 shows the relative importance of the predictor variables, in terms of their percentage contribution to the variance in the outcome variables (HA). Among the microcredit related variables, membership with Grameen bank was the most important predictor of HA, followed by BRAC, BRDB, and ASA. The relative importance of the predictor variables varied substantially between male- and female-headed households.

Figure 1.

Variable importance plot.

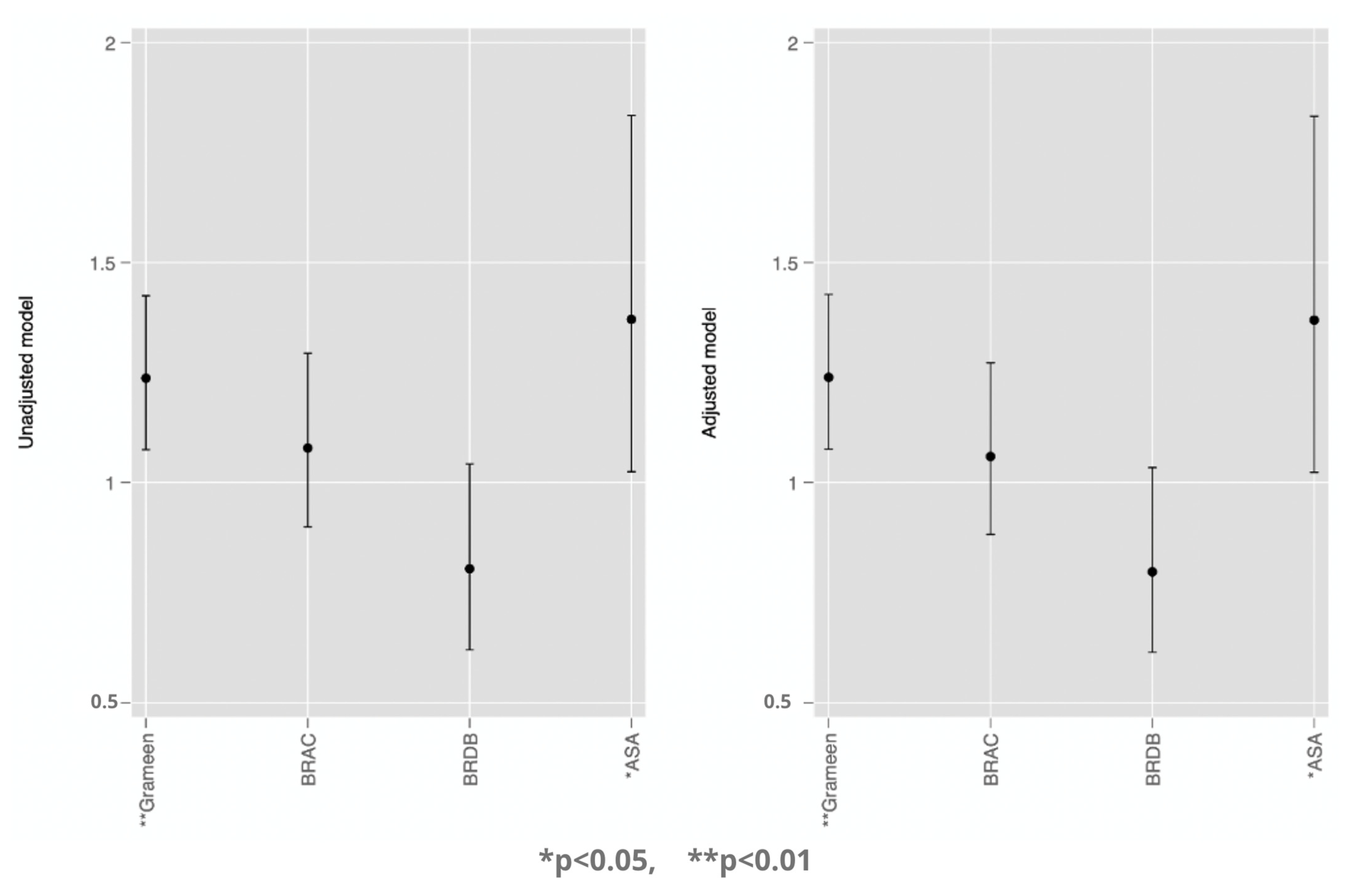

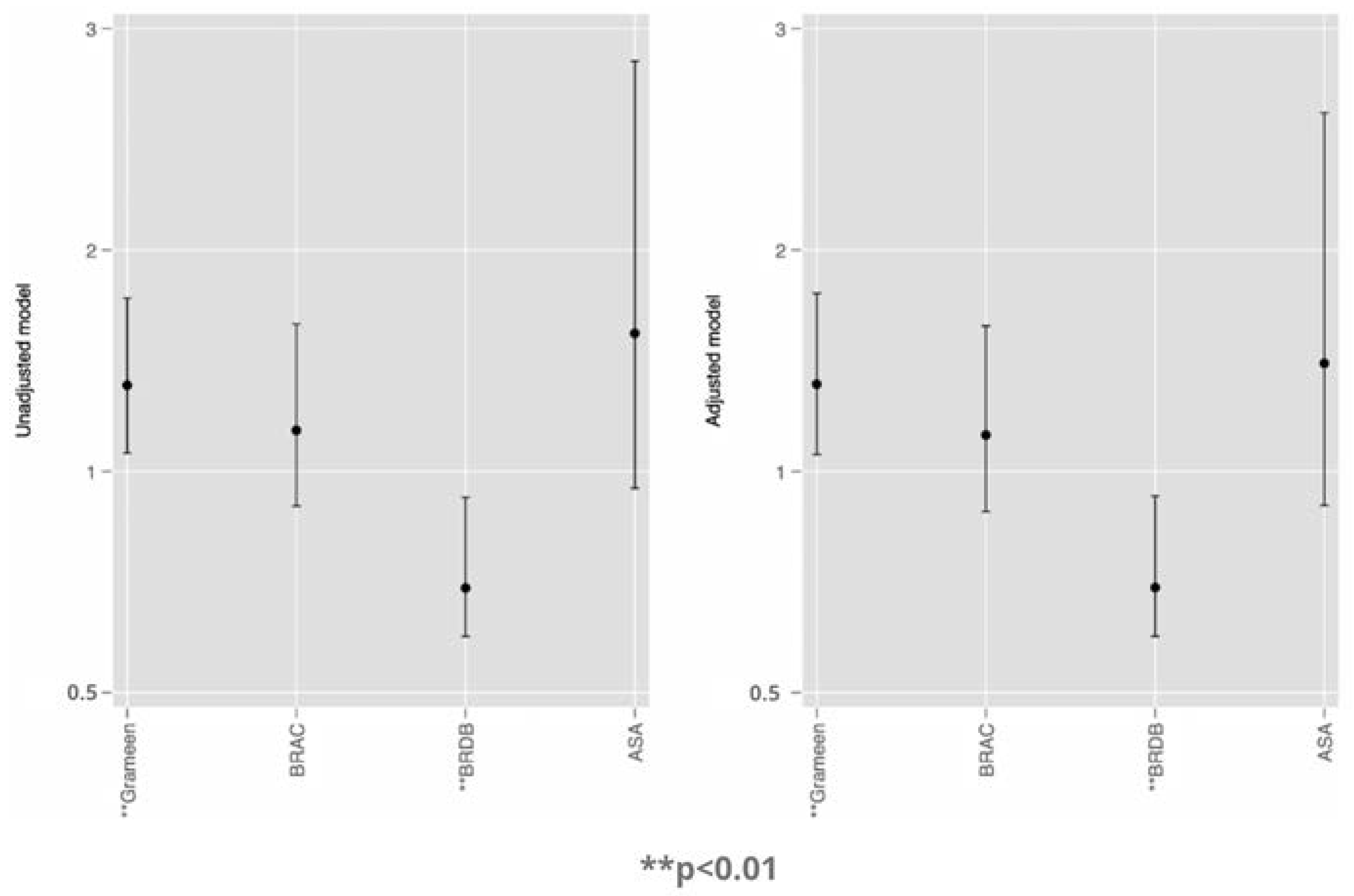

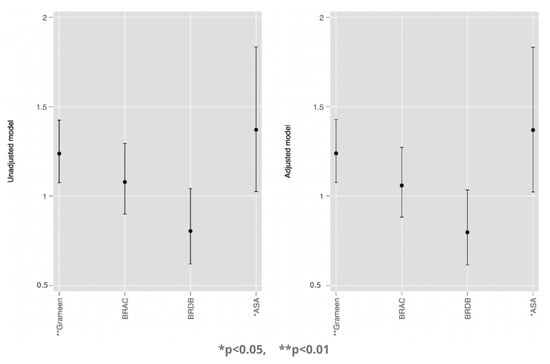

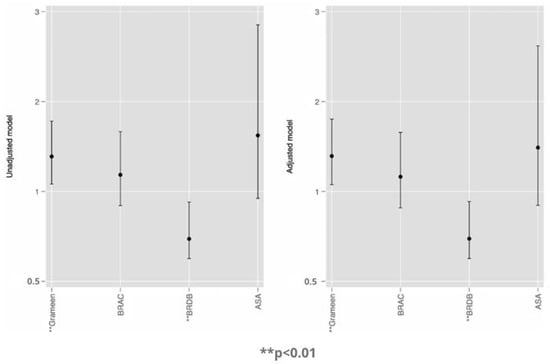

We ran four additional regression models, by stratifying the analysis by survey year (Figure 2 and Figure 3). We found that microcredit membership with Grameen and ASA was associated the increased odds of HA in 2004, whereas in the 2014 surveys the association was positive for Grameen and BRDB, but not for ASA.

Figure 2.

Association between MC membership and health autonomy (BDHS 2004) [21].

Figure 3.

Association between MC membership and health autonomy (BDHS 2014) [21].

4. Discussion

Several noteworthy findings emerged from both the descriptive and multivariate analyses. Notwithstanding the general improvement in the empowerment/sociodemographic indices (e.g., enrolment in secondary and tertiary education, labor market participation) between 2004 and 2014, the proportion of women reporting HA also dropped significantly during the period. More than one-fifth of the participants reported having HA in 2004 compared with 15% in 2014, far lower than the scenario that Meskele et al. reported based on a sub-national analysis among Ethiopian women [26]. Our finding is counterintuitive, in the sense that rising SES in general correlates positively with better economic dependence, which in turn is expected to enhance autonomy. We further observed that in 2004, a marginally higher proportion of women were living in the households of higher wealth quintiles (middle, richer, and richest), which is consistent with the finding that the overall percentage of MC memberships has also decreased during this period. In a general sense, more women are joining the labor force and experiencing higher wealth status, equated to a gradually lower reliance on taking microloans. Given the strong economic growth during the last two decades [27], with appreciable achievements in women’s health and SES [28,29], the downward trend in HA among Bangladeshi women is counterfactual and remains open for further investigation.

The results of the multivariate analysis revealed a mild, but positive, association between HA and having a MC membership with Grameen Bank, BRDB, and ASA. This association could be explained by their pro-women policy and placing women-empowerment at the core of their poverty and hunger alleviation strategy [30,31]. Interestingly, this association was true for women in male-headed households only. Among the female-headed household, only Grameen bank membership showed a positive association with HA. The current analysis does not have sufficient data to explain why microcredit memberships tend to have better impact on women’s HA in male-headed households. However, this might imply that women are not necessarily better-off in female-headed households, in terms of HA. Irrespective of these gendered nuances, this finding reaffirms the fact that prioritizing women’s socioeconomic empowerment through MC programs may contribute to their healthcare, and perhaps other aspects of decision-making autonomy as well [32,33]. It is also important to ensure that taking loans should not leave women worse off, especially in the instances where women have to hand over the money to their husbands and consequently have little to no control over the investment or the returns [32]. Husbands’ inability to repay the loan may deepen women’s indebtedness and affect their overall financial well-being and autonomy [15,34].

Based on the insights generated from the present analysis, it is suggested that leveraging the benefits of MC interventions can contribute to better HA among Bangladeshi women. However, addressing this situation may be trickier among the most marginalized, as the benefits of empowerment interventions may be overshadowed by entrenched poverty and the accompanying vulnerabilities. At the same time, it is important to not lose sight of the sociocultural dimensions of HA, such as the established social norms and values that can undermine women’s capacity to assume roles as vital as deciding their own healthcare, especially ones that are traditionally characterized as masculine roles.

Strengths and Limitations

To our best knowledge, this is the first study to assess the relationship between MC membership and healthcare autonomy among women. The findings are expected to provide crucial insights for the ongoing MC programs targeting the improvement of women’s autonomy and welfare in Bangladesh, and perhaps in other south Asian countries as well. We also provided a brief narrative review regarding the origin of low HA among women, which can inform important perspectives for future research in the region. Among the main strengths of this work were the large sample size, representativeness, quality of the data, and methodological rigor. The robustness of the findings were affirmed by the good predictive power of the models. Using two rounds of surveying enabled us to see how the strength of the predictors of HA varied during these ten years. Another important point of our study was the gendered analysis; i.e., stratifying the analyses by the sex of household head. This allowed us to explore how the associations compared between male- and female-headed households. It is important to note that the findings are generalizable for women aged 15–49 years only. An important limitation was that we were unable to assess the sociocultural influence on HA, which could have altered the strength of the associations. In addition, the variables were self-reported and are subject to recall bias. It is also possible that some women prefer to give answers that they believe to be more desirable and/or socially appropriate. Another important limitation is that the survey might have included only the current microloan borrowers, and from a limited number of institutions. Adding participants from a wider list of institutions and separately for current and former borrowers with the exact length of membership would have allowed us to better understand the relationships between MC and HA. Furthermore, healthcare autonomy is a complex and multifaceted construct, and may not have been captured adequately by the questions used in the DHS program. The percentage of membership with ASA was very low during the 2014 survey, and hence the association for the variable remains subject to type II errors. Finally, the surveys were cross-sectional, and hence the associations cannot guarantee any causal relationship. Future studies should focus on the sociocultural aspects of HA and whether its relationship with MC membership is sensitive to nuances specific to Bangladeshi culture. Our next research goal is to better explain the mechanisms through which MC membership contributes to women’s empowerment, through conducting further qualitative studies on women’s lived experiences.

5. Conclusions

Our findings suggest that microcredit membership with Grameen bank is significantly associated with higher subjective healthcare autonomy among Bangladeshi women. Increasing the coverage of these programs by making them more gender-oriented may, therefore, translate to better healthcare autonomy in this population. While interpreting these findings, it should also be kept in mind that microcredit lending is not a cure-all, but one of many strategies for addressing low health autonomy challenges. Culture-based interventions targeting the family values that diminish women’s decision-making power should be given equal priority.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.G.; methodology, J.E; software, S.G.; validation, J.E., formal analysis, B.G.; data curation, B.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.G; writing—review and editing, J.E.; visualization, B.G.; supervision, J.E.; project administration, B.G.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable, data were secondary and available in the public domain.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants gave informed consent prior to taking part in the survey.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.

Conflicts of Interest

None to declare.

Abbreviations

| BRAC | Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee |

| BRDB | Bangladesh Rural Development Board |

| ASA | Association for Social Advancement |

| BDHS | Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey |

| EAs | enumeration areas |

| HA | Healthcare autonomy |

| MC | Microcredit |

| SES | Socioeconomic status |

| NIPORT | National Institute of Population Research and Training |

| USAID | US Agency for International Development |

References

- Government Committed to Women’s Empowerment in Bangladesh. Available online: https://borgenproject.org/womens-empowerment-in-bangladesh/ (accessed on 17 November 2018).

- Women Empowerment: Bangladesh Sets Example for the World. Available online: https://www.dhakatribune.com/opinion/special/2018/07/12/women-empowerment-bangladesh-sets-example-for-the-world (accessed on 17 November 2018).

- Rahman, M.M.; Khanam, R.; Nghiem, S. The Effects of Microfinance on Women’s Empowerment: New Evidence from Bangladesh. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2017, 44, 1745–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Junankar, P.N.; Mallik, G. Factors Influencing Women’s Empowerment on Microcredit Borrowers: A Case Study in Bangladesh. J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2009, 14, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdousi, F. Impact of Microfinance on Sustainable Entrepreneurship Development. Dev. Stud. Res. 2015, 2, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzetti, L.M.J.; Leatherman, S.; Flax, V.L. Evaluating the Effect of Integrated Microfinance and Health Interventions: An Updated Review of the Evidence. Health Policy Plan 2017, 32, 732–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molla, A.A.; Chi, C. Who Pays for Healthcare in Bangladesh? An Analysis of Progressivity in Health Systems Financing. Int. J. Equity Health 2017, 16, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S. ‘More Health for the Money’: An Analytical Framework for Access to Health Care through Microfinance and Savings Groups. Community Dev. J. 2014, 49, 618–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Annear, P.L. Overcoming Access Barriers to Health Services through Membership-Based Microfinance Organizations: A Review of Evidence from South Asia. WHO South East Asia J. Public Health 2014, 3, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, A.M.; Nababan, H.Y.; Hanifi, S.M.M.A. Building Social Networks for Maternal and Newborn Health in Poor Urban Settlements: A Cross-Sectional Study in Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.M. Capability Development among the Ultra-Poor in Bangladesh: A Case Study. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2009, 27, 528–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hadi, A. Management of Acute Respiratory Infections by Community Health Volunteers: Experience of Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC). Bull. World Health Organ. 2003, 81, 183–189. [Google Scholar]

- Hadi, A. Fighting Arsenic at the Grassroots: Experience of BRAC’s Community Awareness Initiative in Bangladesh. Health Policy Plan 2003, 18, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.A.; Wakai, S.; Ishikawa, N.; Chowdhury, A.M.R.; Vaughan, J.P. Cost-Effectiveness of Community Health Workers in Tuberculosis Control in Bangladesh. Bull. World Health Organ. 2002, 80, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jolly, S.P.; Rahman, M.; Afsana, K.; Yunus, F.M.; Chowdhury, A.M.R. Evaluation of Maternal Health Service Indicators in Urban Slum of Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmud, S.; Shah, N.M.; Becker, S. Measurement of Women’s Empowerment in Rural Bangladesh. World Dev. 2012, 40, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, M.U.; Chowdhury, M.S. The Experience of Microfinance Recipients of Bangladesh Rural Development Board: A Case Study on Integrated Rural Women Development Programme. Bangladesh J. Public Adm. 2019, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Develtere, P.; Huybrechts, A. The Impact of Microcredit on the Poor in Bangladesh. Altern. Glob. Local Political 2005, 30, 165–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microcredit “Death Trap” for Bangladesh’s Poor. BBC News. 2010. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/business-11664632 (accessed on 17 November 2018).

- Roodman, D. Microcredit Doesn’t End Poverty, despite All the Hype. Washington Post. 2012. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/microcredit-doesnt-end-poverty-despite-all-the-hype/2012/01/20/gIQAtrfqzR_story.html (accessed on 17 November 2018).

- Ghose, B. Frequency of TV Viewing and Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity among Adult Women in Bangladesh: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e014399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIPORT/Bangladesh. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2014. 2016. Available online: http://www.niport.gov.bd/ (accessed on 17 November 2018).

- Osamor, P.E.; Grady, C. Women’s Autonomy in Health Care Decision-Making in Developing Countries: A Synthesis of the Literature. Int. J. Womens Health 2016, 8, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osamor, P.E.; Grady, C. Autonomy and Couples’ Joint Decision-Making in Healthcare. BMC Med. Ethics 2018, 19, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishwajit, G. Household Wealth Status and Overweight and Obesity among Adult Women in Bangladesh and Nepal. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2017, 3, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemayehu, M.; Meskele, M. Health Care Decision Making Autonomy of Women from Rural Districts of Southern Ethiopia: A Community Based Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Womens Health 2017, 9, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, C.B.; Haider, M.Z.; Das, D.K. Dynamics of Economic Growth, Investment and Trade Openness: Evidence from Bangladesh. S. Asian J. Macroecon. Public Financ. 2017, 6, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainuddin, A.; Ara Begum, H.; Rawal, L.B.; Islam, A.; Shariful Islam, S. Women Empowerment and Its Relation with Health Seeking Behavior in Bangladesh. J. Fam. Reprod Health 2015, 9, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Nazneen, S.; Hossain, N.; Sultan, M. National Discourses on Women’s Empowerment in Bangladesh: Continuities and Change. IDS Work. Pap. 2011, 2011, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernasek, A. Banking on Social Change: Grameen Bank Lending to Women. Int. J. Politics Cult. Soc. 2003, 16, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morshed, A. Building Empowerment: Female Grameen Entrepreneurs in Rural Bangladesh. S. Asia J. S. Asian Stud. 2014, 37, 605–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, S. Why Micro-Credit May Leave Women Worse Off: Non-Cooperative Bargaining and the Marriage Game in South Asia. J. Dev. Stud. 2013, 49, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.K.; Kundu, A. Microcredit and Women’s Agency: A Comparative Perspective across Socioreligious Communities in West Bengal, India. Gend. Technol. Dev. 2012, 16, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garikipati, S. The Impact of Lending to Women on Household Vulnerability and Women’s Empowerment: Evidence from India. World Dev. 2008, 36, 2620–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).