Abstract

Frontline workers are instrumental in bridging the gap in the utilization of maternal health services. We performed a qualitative cross-sectional study with medical officers, accredited social health activists (ASHA), and auxiliary nurse midwifes (ANM), across 13 districts of India, in order to understand the barriers and enablers, at the system and population levels, for improving access of adolescents and mothers to services. The data were collected by means of in-depth interviews (IDI) with medical officers and focus group discussions (FGD) with ASHA and ANM in 2016. The interview guide was based on the conceptual framework of WHO health interventions to decrease maternal morbidity. Content analysis was performed. In total, 532 frontline workers participated in 52 FGD and 52 medical officers in IDI. Adolescent clinics seemed nonexistent in most places; however, services were provided, such as counselling, iron tablets, or sanitary pads. Frontline workers perceived limited awareness and access to facilities among women for antenatal care. There were challenges in receiving the cash under maternity benefit schemes. Mothers-in-law and husbands were major influencers in women’s access to health services. Adolescent clinics and antenatal or postnatal care visits should be seen as windows of opportunities for approaching adolescents and women with good quality services.

1. Introduction

Women and adolescents have long faced health challenges in the low- and middle-income countries of the world. Improvement in women’s health increases the productivity of the nation and free resources that can be used for childcare, feeding, and education, contributing to an increase in future productivity [1]. Pregnancy and childbirth are important phases in a woman’s life that have health implications over the rest of their lives. Maternal health, during and after pregnancy, has largely been focused on preventing maternal mortality and morbidity. The use of maternal health services reduces maternal mortality and improves the reproductive health of women [2]. There are wide disparities in access to maternal health services across regions. Limited availability and underutilization of available maternal services have been found in the populations that need them the most, i.e., marginalized people [3].

India, despite reducing maternal mortality significantly, from 385 per 100,000 live births in 1990 to 216 per 100,000 live births in 2015, faces challenges in ensuring universal access to maternal health services for all [4]. According to the national family health survey in 2015–2016, only one in two women had four antenatal care check-ups, one in three women consumed 100 iron-folic acid tablets and received financial assistance under the maternal conditional cash transfer scheme [5]. Multiple factors culminate to result in the low utilization of maternal health services, including low awareness, education status, the decision-making power of women, beliefs and customs in society, poor socioeconomic status, and lack of quality service delivery [6,7,8].

The life-course approach advocates for the provision of services and care from adolescence to adulthood and helps women prepare for pregnancy and equally good postnatal care [9]. The national adolescent health program of India aims to ensure that all adolescents in India are able to realize their full potential by making informed and responsible decisions related to their health and well-being and accessing the services and support they need to do so. To accomplish this objective, adolescent-friendly health clinics have been integrated into hospitals or health centers in selected districts, so that adolescents can access counselling and curative services or be referred to a specialist for further care [10]. Health workers, especially the frontline workers and medical officers, have been trained in delivering adolescent-friendly health services [11]. However, studies suggest a huge gap between the awareness and utilization of adolescent health services in the communities [12,13].

Frontline workers are instrumental in bridging the gap in the utilization of maternal health and nutrition services and preventing maternal mortality in the community [14,15]. Effective counselling and outreach services, by frontline workers, will help to strengthen health systems and improve coverage. Auxiliary nurse midwives (ANM) and accredited social health activists (ASHA) are an integral part of the Indian health system and key human resources in delivering maternal and adolescent health services [14]. Frontline workers disseminate health-related information, educate, and interact with women and their families to improve the utilization of maternal and adolescent health care services and supervise or monitor national health programs in the community [16].

Since frontline workers are in direct contact with communities and women, they are an important source to gather information about the needs of women and adolescents, services they offer, and gaps in those services. Furthermore, frontline workers, such as ASHA, come from the same village; they are well aware of the challenges and barriers that women and socially marginalized communities are facing [17,18]. It is indeed crucial to understand their perspectives and thoughts and invite suggestions from them, while aiming to improve the utilization of maternal or adolescent health services. Multiple studies in the past reported the challenges and barriers in accessing health services and the reasons for the same, from users’ perspectives. However, very few have illustrated frontline workers’ perspectives [19,20,21,22]. Furthermore, the available data on frontline workers’ perceptions are limited to particular geographies, without much focus on the socially marginalized sections (scheduled caste, tribes, or other marginalized classes) of the society that had the least probability of accessing health services in the community [23,24]. Considering the lack of adequate evidence on frontline workers’ perceptions, regarding barriers in the utilization of maternal and adolescent health services and services they provide, we aimed to perform a qualitative study with medical officers, ASHA, and ANM across 13 districts of India. The qualitative study was conducted with the objective to understand the barriers and enablers, at the system and population level, in improving access of adolescents and mothers to health and nutrition services.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

This study was conducted as a part of the baseline assessment of key maternal and adolescent health indicators in a project that aims to improve the uptake of antenatal, postnatal, and adolescent health services across 13 districts of India. The 13 districts included five from Uttar Pradesh (Banda, Kaushambi, Lucknow, Prayagraj, and Varanasi), two each from Rajasthan (Churu and Ganganagar) and Bihar (Patna and Jamui), and one each from Delhi (West Delhi), Maharashtra (Nagpur), Karnataka (Bangalore), and Chandigarh. We chose two blocks per district, except in Rajasthan, where four blocks per district were chosen.

2.2. Data Collection

Qualitative data were collected by two investigators per district. All the investigators undertaking qualitative data collection were trained in different qualitative methods and had experience in the design, conduct, and analysis of face-to-face survey work. The researchers preferred to note down responses to record spoken interactions in the interviews and group discussions. The data were collected by means of in-depth interviews (IDI) with medical officers at primary health centers and focus group discussions (FGD) with frontline health workers, such as ASHA and ANM. We opted for medical officers and frontline workers who were working in the areas for the past one year. Two IDI and two FGD per block were performed; hence, 52 IDI and 52 FGD were conducted across 13 districts. Purposive sampling was adopted to recruit participants for the study. MAMTA has been working in the area for ten years; hence, we did not face difficulty in approaching the frontline workers or officers. The number of FGD or IDI to be conducted were decided beforehand. Data were collected using semi-structured interview guides, with closed and open-ended questions. The respondents were recruited with the help of the field teams that sought approval for the interview beforehand. The interviews and discussions took place in the local language (Hindi/Kannad) in 2016.

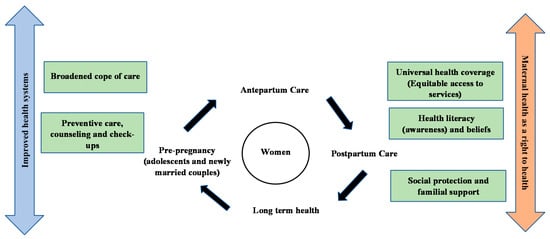

The interview guide was based on the conceptual framework of the study (Figure 1) [25]. Within the study framework, we sought to explore the perceptions of officers and frontline workers on five domains. These included equitable (universal) access to services, health awareness, beliefs of women, familial support, social protection of women, preventive check-ups, counselling, and broadened scope of care. Equitable access to services, health awareness, beliefs, and familial support aimed to illicit the barriers in the utilization of services. Preventive check-ups and broadened scope of care were included to highlight services provided by frontline workers.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for the qualitative study. The figure illustrates the five domains of healthcare interventions to improve maternal health, including universal health coverage, health awareness and catering beliefs among women, seeking familial support, preventive care and check-ups, and broadened scope of care. The framework also highlights the approaches to deliver these interventions, including antenatal care, post-partum care, and pre-pregnancy care for improved longterm health. The improved health system and ensuring maternal health as a right to health will be the paradigms for decreased maternal mortality or increased access to maternal health services.

All the interviews were hand-written (after obtaining consent from all the participants), transcribed, and translated into English. The mean duration of a focus group discussion was 75 min (range: 60–90 min). The mean number of participants in the focus groups was 10–15. All the focus groups were physically conducted at a suitable place in villages/slums. Out of two, one investigator was in charge of moderating, with the other transcribing, the IDI or FGD. All the investigators used the same protocol, a document with the main topics to cover. Verbal informed consent was obtained from the participants before the interviews/discussions. The quality and reliability of the translation for all the recorded data into English was ensured.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

A content analysis was carried out to identify themes, based on the framework. The corpus of this qualitative study was shaped by the content of the FGD and IDI. A coding table was created to list the different categories of answers. Two tables were used, one for the focus group content and another for the interview content. This codification was simultaneously done manually by two people from the team to guarantee content validity. Moreover, once this codification was done, it was debated with other members of the team, in order to obtain a second validation on the content categorization. It was decided that no modification of the corpus should be done. This means that unclear quotes were not “re-transcribed” or written in more comprehensible English. This might introduce a potential bias and would result in an analysis founded on modified information.

After that, the responses recorded in the excel sheets were read and re-read, to get a sense of the interviews, before sorting them into parts, as per the thematic framework. The data were extracted from the responses generated across various sections of the interview schedules, thereby creating a comprehensive data pool for each theme. Once the responses were reduced to the themes, we interpreted them to provide an insight into the issues that were emerging from the data.

The interview data were anonymized in such a way as to make sure neither the respondents themselves nor the people they were referring to in the interview (such as trainers, institutions, etc.) could be identified. The interview transcripts contained no information allowing for linking back the interview data to the survey responses of the interviewee. The ethical clearance of the interview guides was granted by the MAMTA Ethical Review Board.

3. Results

In total, 532 frontline workers participated in the FGD and 52 medical officers in the IDI. Nearly two-thirds of the participants belonged to socially marginalized populations (those belonging to scheduled castes, tribes, and other marginalized classes). The results have been categorized into six parts, including adolescent-friendly health services, antenatal care, postnatal care services, nutrition, hygiene, and miscellaneous.

3.1. Adolescent Friendly Health Services

- Preventive care, counselling, check-ups, and familial support: Adolescent health clinics did not exist in most of the places; however, adolescent health services were provided, particularly counselling. In urban areas, such as Chandigarh, Delhi, and Nagpur, Anganwadi (maternal and childcare centers) were the counselling place for adolescents. In Bangalore, such clinics were running under the name of ‘SNEHA’ clinics; however, they did not seem to be functioning properly. In Banda, girls were provided sanitary pads and iron tablets. There were counsellors at community health centers who provided health-related services to adolescent boys and girls. There were challenges for adolescents to access clinics because of a lack of conducive environment (lack of electricity and cleanliness) and support from families. There were adolescent reproductive and sexual health (ARSH) clinics at few places in Varanasi. Medical officers informed that the most common issues adolescents came to the clinics with included pimples, infections, menstruation-related problems, genital discharge, nightfall, skin-related problems, anemia, and malnutrition. In Churu, boys were informed about the harms of tobacco, substance, and alcohol abuse. ASHA and ANM seemed to be the source of discussion for problems with girls. However, in Ganganagar, even counselling for girls was absent.

“Though only a few adolescents come to us, most are malnourished; many are anxious about the physical changes happening in their bodies and are unaware of these changes, some suffer from sexual problems and are hesitant or feel embarrassed to discuss the same with us”.(Medical Officers during IDI in Nagpur)

“Due to absence of electricity and good environment at health facilities, adolescent girls don’t come there”.(Frontline worker during FGD in Prayagraj)

- b.

- Broadened scope of care: Outreach activities were not done often; however, adolescent issues were discussed or raised during the village health and nutrition days. Medical camps were organized by frontline workers in Bangalore. Adolescent health issues were common, but there were no special clinics. Medical officers made regular school visits in Kaushambi for screening and counseling adolescents. Community meetings were held with adolescents to explain hygiene.

- c.

- Health literacy and beliefs: In Lucknow, superstition beliefs (tantrik, baba, jhaadphook) and access to medicasters (jholachaap doctors) for routine adolescent ailments was common. Medical officers informed that girls felt threatened while talking to outsiders, such as doctors or nurses, at the health centers. Adolescents did not access health facilities because of society’s norms and a lack of separate facilities to address their issues and provide confidential counselling and care. It also appeared, from the interviews, that issues of adolescent boys were not discussed that often.

3.2. Antenatal Care Services

- Preventive check-ups and counselling: Medical officers and frontline workers informed about the need to create awareness about antenatal care among women. In the move to generate this awareness, they educated women about the danger signs of pregnancy, such as swelling in the hands and feet, high blood pressure, fits, and heavy bleeding, at centers and during home visits. They provided information about institutional delivery and its importance and benefits, as well as antenatal care, including the measurement of haemoglobin levels, consumption of iron tablets, measurement of protein levels in urine, thyroid tests, blood pressure, weight monitoring, and tests for Hepatitis B and HIV. The doctors and frontline workers did discuss the consequences and treatment of anaemia, a good diet, the importance of iron-folic acid tablets, and tetanus toxoid injections. Frontline workers appeared to run antenatal clinics twice a week and vaccinate mothers and children. Frontline workers counseled women about family planning methods, breastfeeding, and early newborn care.

The lack of emergency ambulance services was highlighted during the interviews in Banda. There was a lack of good infrastructure at government facilities. Women appeared to have difficulty in accessing the government schemes, such as Janani Suraksha Yojna (conditional cash transfer scheme), as they did not get money for institutional delivery because of a lack of proper identity proofs and bank accounts. Lack of instruments and services at government facilities, such as ultrasound scanning and laboratory facilities, discouraged women from accessing them during pregnancy. Also, primary health centers were located far away from villages (25–30 km).

- b.

- Health awareness and beliefs: Besides the lack of awareness, superstitious beliefs and myths were prevalent among women. Some communities were hesitant to vaccination in Varanasi and Jamui.

“If a pregnant woman eats more than two times a day, the child may be pushed under the food and may die of suffocation, and woman should not sleep in the afternoon; otherwise, the child born will be lazy”.(Frontline worker during FGD in Varanasi)

Frontline workers perceived that women do not visit government centers because of the rude behaviour of doctors and long queues. Frontline workers perceived that woman did not trust government services; hence, they did not access these services, despite awareness campaigns and counselling. Women were hesitant to turn up for check-ups in a facility with a male doctor. Frontline workers made micro-plans for their activities in Kaushambi. High home delivery rates in Kaushambi appeared to be because of illiteracy, delay in seeking care, lack of knowledge, ignorance, overdependence on families, beliefs, customs, and non-compliance to the advice of the health workers.

- c.

- Broadened scope of areas (Services): Frontline workers perceived that marginalized populations did not pay attention to their diet and health. However, frontline workers tried their best to implement the national health programs/state health programs at the village level and make people aware of the government policies. They counselled young couples to delay the birth of the first child and maintain a gap of two years between two successive pregnancies and received INR 500 to motivate couples to adopt contraceptives. Information was spread to women through non-governmental organizations, women’s groups, and village health and nutrition days. Women delivered in hospitals in cities such as Delhi. The outreach activities of doctors and workers were good in Lucknow. Subcenters were visited by doctors (twice a month) and frontline workers (thrice a month). Young couples were counselled by frontline workers on contraceptives and nutrition. It appeared that ASHA/AWW made home visits to pregnant women to generate awareness.

“Women committees are platforms where we discuss antenatal and postnatal care with pregnant and lactating women”.(Frontline workers during FGD in Nagpur)

- d.

- Equitable access to services: It was perceived from the interviews that women in urban areas were better informed and utilizing maternal health services better than the rural areas. Also, women from the marginalized communities, such as those who were scheduled castes, tribes, or from economically weaker sections, seemed to be unaware of most of the information and had limited access to services.

“Marginalized community women are accessing government facilities; apart from above the poverty line cardholders, below the poverty line cardholders are eligible for Madilu Kit in Bangalore”.(Frontline workers from FGD in Bangalore)

The ‘Madilu’ program was initiated by the government of Karnataka to promote institutional delivery and reduce maternal deaths. In the program, mothers were provided ‘Madilu’ kits, which contained items, such as soap, hair oil, socks (for the child), cotton diapers, flannel, bedspreads, abdominal belts, rubber sheets, and sweaters, etc., for the mother and child.

3.3. Postnatal Care Services

- Preventive check-ups and counselling: Frontline workers provided postnatal check-ups twice a week. Medical officers and frontline workers informed women about postnatal danger signs, such as bleeding, fever, etc. Additionally, they were informed of symptoms such as the irregular heartbeat of the child, the child turning blue, etc. Frontline workers counseled women on how to take care of the newborn, i.e., immediate breastfeeding, continued breastfeeding for six months, sponge bath, feeding schedule, precautions, and care against illnesses, such as diarrhea; they also provided zinc tablets (1/2 for below 6 months of age and one tablet for above six months), oral rehydration solution (ORS), immunization, and vaccination. Additionally, frontline workers counseled women on maternal nutrition and family planning methods, such as oral pills, copper T, depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA), etc. Frontline workers had informed women about post-natal check-ups until 14 days of delivery and provided iron-folic acid tablets. Lack of facilities, such as the shortage of medicines, electricity supply, etc., and long queues seemed to prevent women from accessing government health centers. Some women delivered at home and not in hospitals.

“Some women are not interested in delivering in hospitals because copper-T is inserted and sometimes sterilization is done without consent or forcefully by nurses or doctors”.(Frontline workers during FGD)

- b.

- Health awareness and beliefs: Frontline workers perceived that women were unaware of postnatal care services across most of the places. Women seemed to be reluctant to access postnatal care services for their children until (and unless) the child fell sick. Women seemed to believe that once a child is taken to the doctor, then the child will always remain ill. It appeared from the interviews that women believed vaccination might stop the growth of their children or make them impotent.

“Women don’t take children to vaccination so as not to let evil eye spoil them!”.(FGD with Frontline workers in Varanasi)

“Women think that due to immunization, their children will become impotent”.(FGD with Frontline workers in Banda)

- c.

- Broadened scope of services: Frontline workers made door-to-door visits for the post-natal check-up of mothers and children and fed them protein-rich food at Anganwadi centers. ASHA workers maintained the records of delivered mothers, ensured their presence in village health and nutrition day meetings, and followed up with the dropouts under the Indradhanush program of immunization. Frontline workers made micro-plans to reach women in the communities. Frontline workers made women aware of the government’s policies and programs for mothers. Doctors visited subcenters, especially during mother and child vaccination days. The lady health visitor visited the subcenter thrice in a month, with outreach through ANM and ASHA.

“Immunization and family planning camps and disability camps are planned and organized in the communities”.(Medical officer during IDI in Bihar)

- d.

- Equitable access to services: Women from economically weaker communities seemed to lack information about postnatal care information. It appeared that some women were not able to receive the benefit of government cash transfer schemes (Janani Suraksha Yojna) because of a lack of proper (proof of) identity and a bank account. Women with no savings found it difficult to open an account to receive cash benefits from the government. Migration of women post-delivery and a huge documentation process for cash benefits’ registration seemed to decrease women’s access to postnatal care services. Additionally, women were hesitant to visit government facilities for care or obtain benefits because many were daily wagers, and a visit to a hospital spent their entire day with a loss of their wages. There was limited access to postnatal care services for women in the urban areas, as well. Frontline workers said that they did not discriminate among women from different socio-economic backgrounds when providing services. On the contrary, some frontline workers appeared to follow up with women not coming for regular check-ups through personal visits or phone calls.

- e.

- Familial support: Most of the time, frontline workers ensured that women received care within 48 h of delivery; however, sometimes, mothers-in-law and husbands took women home right after delivery. Thus, frontline workers perceived a need to create awareness about the significance of postnatal care amongst husbands and mothers-in-law. Mothers-in-laws influenced the decision-making process of a woman and prevented them from undergoing sterilization in Churu.

3.4. Nutrition

- a.

- Preventive check-ups and counselling: Medical officers perceived that anemia and malnutrition were common among women, and they lacked awareness about health and nutrition. Women were perceived to have calcium deficiency and its related problems. They made women, including adolescent girls and newly married women, aware of the negative consequences of anemia and how to cure it. They counseled women about the consumption of green vegetables, pulses, salads, milk, and curd and made them aware of the significance of nutritious food during antenatal and postnatal check-ups. Frontline workers made women aware of the nutritious diet through scheduled home visits. They provided iron-folic acid tablets and organized camps for the screening of malnourished children. Many women could not afford a balanced diet because of poverty. They highlighted the need to ensure food security to women from economically weaker sections of society. Some frontline workers perceived that, instead of money, women should be given food items directly.

- b.

- Equitable health services: Medical officers perceived a lack of nutrition among women from economically weaker backgrounds. It appeared that there was a lack of awareness, illiteracy, migration for employment, superstition, and purdah system among marginalized societies.

- c.

- Broadened scope of care: It was highlighted, during the interviews in Nagpur, that pregnant women were given nutritious food packets, as well as packets of Chikki (a sweet snack prepared from peanuts and enriched with protein, minerals, and vitamins), in Anganwadi centers. Other nutritious foods (local Indian foods rich in protein) that were given in the Anganwadi, such as Chiwda, papdi, chane, poha, khichdi, etc., have to be given with force, as they do not take it. Camps were organized for women on nutrition counselling.

3.5. Hygiene

- a.

- Health awareness and beliefs: Frontline workers said that women need to know about hygiene and its relation to health, they need to focus on hygiene post-delivery, and adolescents need to be made aware of hygiene. It seemed that women lacked personal hygiene, and infections were common in the communities.

- b.

- Broadened scope of services: ASHA and ANM spread awareness about cleanliness amongst women, as well as adolescents, and organized health camps and provided information and services to address various problems. Frontline workers called adolescents to the Anganwadi centers, where they were given iron tablets and sanitary pads and were told about hygiene. Women and adolescent hygiene issues were raised during village and health nutrition days.

3.6. Miscellaneous

ASHA could not meet newly married women, and these women could not reach medical officers, as they were not allowed to step out of their houses. Because of lack of awareness about contraceptives, women became pregnant soon after pregnancy, and their health deteriorated. Frontline workers found it difficult to change people’s mindsets in villages due to strong cultural beliefs. The newlyweds were embarrassed to talk about family planning issues because of superstitious beliefs and cultural norms in society. The elders in the family seemed to advise young couples to conceive soon after marriage. In general, women had problems like high blood pressure, vaginal discharge, lower back pain, and irregular periods, etc. Some women did not want to use family planning methods, as they believed that it would harm their capability to conceive later on. Some women seemed hesitant to get their children vaccinated because of the fear of side effects, such as fever.

“Newly married women who are not pregnant could not be provided education on health and nutrition by ASHA because of pardha system and superstitious beliefs; their husbands and mothers-in-law don’t allow them to meet ASHA workers, such women despite having sexual or reproductive tract infections are not allowed to go to primary or community health centers by their mothers-in-law”.(Medical Officer during IDI in Banda)

“There is a high prevalence of domestic violence here; we receive a lot of domestic violence victims with injuries”.(Medical Officer during IDI in Bihar)

The key gaps identified during the interviews in adolescent health, antenatal and postnatal care, nutrition, and hygiene services are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summarization of the gaps in adolescent health, antenatal and postnatal care, nutrition, and hygiene services, as revealed during FGDs and interviews.

4. Discussion

The present qualitative study highlighted the barriers and enablers for access to maternal or adolescent health services in the communities, from the perspectives of health workers. The findings underlined the frontline workers’ efforts and role towards ensuring universal access to services for all women, irrespective of caste or economic background. We accrued evidence of gaps in the utilization of services along the life-course, i.e., from adolescence to post-pregnancy.

We found, from the interviews, that adolescent health clinics were non-existent in most study areas. Some existed, in certain places, with different names, such as SNEHA or ARSH clinics. However, services were being provided to adolescents, such as counselling, iron tablets, or sanitary pads. Frontline workers conducted meetings in the communities or via visits to schools. There is mixed evidence on the utilization of adolescent-friendly health services. While a study from Maharashtra reported that there had been an increase in the number of adolescents seeking clinics for preventive or curative services, [11] the others reported that only a few adolescent girls/young women, and none of the boys/men, utilized the clinics [11,12,26,27]. Clinics attached to medical colleges or hospitals are accessible, clean, and the timings are appropriate [28].

Services pertaining to resolving queries about physiological changes during adolescence, menstruation- and nutrition-related issues, reproductive tract infections, and skin disorders were sought by adolescents [11,12,13,26]. Quite often, privacy and confidentiality are maintained in clinics, [13,28] but it is still breached in many places [26]. However, providers lacked comprehensive knowledge about the management of adolescent health problems, and their adherence to protocols or guidelines was lacking [13]. We need to strengthen community activities to develop an enabling environment for adolescents. This can be ensured by strengthening the existing health facilities, in order to ensure comprehensive services, contextualized to adolescents’ needs, as well as enhancing the knowledge and skills of ASHAs for mobilizing adolescent clients to the clinics and establishing linkages with school health services.

Adolescents were hesitant or felt embarrassed in approaching doctors or clinics for obtaining services, especially boys. Likewise, Santhya et al., in their report, highlighted that seeking care for sexual and reproductive health remains limited among adolescents because of perceptions that the health issue was not serious enough to do so, an embarrassment in seeking treatment, lack of money and family support, and concerns about the poor quality of care [26].

Our study found that frontline workers had been providing good care and counselling to pregnant or lactating women, through regular clinics or outreach services. However, frontline workers perceived limited awareness and access to facilities among women for antenatal or postnatal care. ASHA workers had been the cornerstone in improving the maternal and child health, as well as the nutrition situation, in the country, including providing counselling, care, and connecting women and adolescents with services. Good communication and liaison between ASHA and ANM workers helped to improve maternal health services in the rural areas, especially improving access to services among marginalized populations [29,30]. Congruent to other studies, we found that women had certain beliefs or customs, related to antenatal check-ups or maternal care, and vaccine hesitancy in certain places [31,32]. These customs or beliefs are passed down from one generation to the other. Also, pregnant women preferred private facilities, due to the lack of facilities in the public hospitals, in our study. Government health facilities are ill-equipped with a lack of resources, staff, doctors, and good infrastructure, resulting in preference of the private hospitals for services and a high out-of-pocket expenditure for poor families [33]. Our findings concur with other studies highlighting the challenges in receiving the conditional cash transfer scheme’s benefits without proper identity or bank accounts [34]. As highlighted in our study, copper-T, inserted without women’s consent, is against her rights and should be dealt aggressively. The government is working actively to ensure respectful maternity care in India to all pregnant women.

Compared with antenatal care, the uptake of postnatal care is poorer among women in India. This is evident from the national family health survey 2015–2016, stating that 84% of women (15–49 years) received antenatal care, compared to 69% of women who received postnatal care. Besides, there are inequalities in the coverage of services, with economically disadvantaged and marginalized women having far less access than their counterparts [35]. Launched in 2014, Mission Indradhanush has targeted underserved, vulnerable, resistant, and inaccessible populations, resulting in a 6.7% increase in the full immunization coverage across India. Frontline workers had been an integral part of the success of the mission. The key factors for the success of the mission included identification of gaps in human or financial resources, microplanning, head counting of beneficiaries, creating fixed outreach sites and mobile teams for vaccination, and regular monitoring [36,37]. However, continued mobilization and awareness of populations is required, with an uninterrupted supply of vaccines and microplanning at the health system’s level, for sustained improvement in immunization for children under five years old [37].

Frontline workers had been counseling women about good food and a nutritious or balanced diet; however, the availability of food is an issue among poor and marginalized populations in India. India is suffering from an alarming hunger, ranking at 100 out of 119 in the global hunger index [38]. The hunger status in India can be equated to chronic food insecurity, where people are consistently consuming a diet inadequate in calories and essential nutrients [38]. Despite food security policies and programs in place, including the food security act, targeted public distribution system, mid-day meals in schools, and supplementary foods in Anganwadi centers, 40% of households are food insecure in Maharashtra [39]. Mid-day meals and supplementary foods at Anganwadi centers are provided, free of cost. Multiple factors enumerated for the limited success of food security policies and programs include inefficiency, miss-targeting, corruption, leakage, and diversion, etc. [40].

Women’s family members, particularly husbands and mothers-in-laws, are key influencers in their decision for access to services. Furthermore, the husbands’ education has been suggested as a key determinant for improving antenatal care coverage among women [8]. So, it is important to target husbands and mothers-in-law in programs for generating awareness about maternal health services [7,8]. Autonomy in decision-making among women comes with education, economic independence, and societal support. Hence, awareness generation programs need to educate women about health and empower them socially for improved confidence and self-decision-making capacity.

Cultural beliefs and social norms are very strong in Indian communities, particularly among marginalized populations. These beliefs many times act as barriers in accessing health and nutrition services, resulting in poor health outcomes [41]. Many such examples include beliefs and norms related to menstrual hygiene, antenatal care, breastfeeding, immunization, and postnatal care of mothers [42,43]. The government of India attempts to address these myths, misconceptions, beliefs, and norms through awareness programs, counselling by frontline workers, or other means of social and behavioral change communication techniques [44,45].

Limitations

The study results should be viewed in consideration of the following limitations. Firstly, the study was limited to understanding perceptions of frontline workers and did not involve the perceptions of women or users of services. This limits the 360-degree representation of the gaps. Secondly, the data were collected through qualitative interviews or group discussions; hence, all the inferences are perception-based and cannot be measured quantitatively. Lastly, selected themes or topics were chosen based on the project’s priority; hence, the data left some other issues/topics related to maternal and adolescent health.

5. Conclusions

The present qualitative cross-sectional study suggests barriers, such as limited health literacy, a lack of good public health infrastructure and facilities, traditional beliefs and customs, socioeconomic inequalities, and a lack of familial support, to the utilization of maternal or adolescent health services. Besides, a lack of privacy, fear, embarrassment, and unfriendly environment at facilities posed challenges for adolescents to access adolescent-friendly health clinics. The key enablers for improved access to services included non-discriminating and equitable care in the facilities and outreach services, through door-to-door visits, community meetings, or school visits by frontline workers to adolescents and women. Husbands and mothers-in-laws were key influencers in decision-making towards the uptake of maternal health services.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S., S.M. and F.A.; methodology, S.S., K.A. and A.B.; formal analysis, S.S. and K.A.; data curation, S.S. and F.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.; writing—review and editing, S.S., A.B., K.A. and S.M.; supervision, F.A. and S.M.; project administration, F.A. and S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was a part of implementation science, which was funded under corporate social responsibility to MAMTA Health Institute.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was provided ethical clearance by MAMTA Ethical Review Board.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Due to institutional policy, data cannot be provided along with the paper, but the same can be made available on a personal request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Surendra Kumar Mishra, as well as the advisors and field investigators who collected the data. We would also like to extend thanks to study participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Report of the Commission on Women’s Health in the African Region: Addressing the Challenge of Women’s Health in Africa. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2017-06/report-of-the-commission-on-womens-health-in-the-african-region-chapter-5.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Hamal, M.; Dieleman, M.; De Brouwere, V.; de Cock Buning, T. Social determinants of maternal health: A scoping review of factors influencing maternal mortality and maternal health service use in India. Public Health Rev. 2020, 41, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Creanga, A.A.; Gillespie, D.G.; Tsui, A.O. Economic Status, Education and Empowerment: Implications for Maternal Health Service Utilization in Developing Countries. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Paul, P.; Chouhan, P. Socio-demographic factors influencing utilization of maternal health care services in India. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2020, 8, 666–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015–2016; IIPS: Mumbai, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.; Neogi, S.B.; Hazra, A.; Irani, L.; Ruducha, J.; Ahmad, D.; Kumar, S.; Mann, N.; Mavalankar, D. Utilization of maternal health services and its determinants: A cross-sectional study among women in rural Uttar Pradesh, India. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2019, 38, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizkianti, A.; Afifah, T.; Saptarini, I.; Rakhmadi, M.F. Women’s decision-making autonomy in the household and the use of maternal health services: An Indonesian case study. Midwifery 2020, 90, 102816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jat, T.R.; Ng, N.; San Sebastian, M. Factors affecting the use of maternal health services in Madhya Pradesh state of India: A multilevel analysis. Int. J. Equity Health 2011, 10, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jacob, C.M.; Baird, J.; Barker, M.; Cooper, C.; Hanson, M. The Importance of a Life Course Approach to Health: Chronic Disease Risk from Preconception through Adolescence and Adulthood. Available online: https://www.who.int/life-course/publications/life-course-approach-to-health.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Barua, A.; Watson, K.; Plesons, M.; Chandra-Mouli, V.; Sharma, K. Adolescent health programming in India: A rapid review. Reproduct. Health 2020, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, B.N.; Chauhan, S.L.; Kulkarni, R.N.; Kamlapurkar, B.; Mehta, R. Operationalizing Adolescent Health Services at Primary Health Care Level in India: Processes, Challenges and Outputs. Health 2017, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mahalakshmy, T.; Premarajan, K.C.; Soundappan, K.; Rajarethinam, K.; Krishnamoorthy, Y.; Rajalatchumi, A.; Mathavaswami, V.; Chandar, D.; Chinnakali, P.; Dongre, A.R. A mixed methods evaluation of adolescent friendly health clinic under national adolescent health program, Puducherry, India. Indian J. Pediatrics 2019, 86, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixit, G.T.; Jain, S.; Mansuri, F.; Jakasania, A. Adolescent friendly health services: Where are we actually standing? Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2017, 4, 820–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lyngdoh, T.; Neogi, S.B.; Ahmad, D.; Sundararajan, S.; Mavalankar, D. Intensity of contact with frontline workers and its influence on maternal and newborn health behaviors: Cross-sectional survey in rural Uttar Pradesh, India. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2018, 37, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gilmore, B.; McAuliffe, E. Effectiveness of community health workers delivering preventive interventions for maternal and child health in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rammohan, A.; Goli, S.; Saroj, S.K.; Jaleel, C.P.A. Does engagement with frontline health workers improve maternal and child healthcare utilisation and outcomes in India? Hum. Resour. Health 2021, 19, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray Saraswati, L.; Baker, M.; Mishra, A.; Bhandari, P.; Rai, A.; Mishra, P.; Chandan, A.; Crockett, M.; Pelly, L.; Anthony, J.; et al. ‘Know-Can’gap: Gap between knowledge and skills related to childhood diarrhoea and pneumonia among frontline workers in rural Uttar Pradesh, India. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2020, 25, 454–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, S.; Radkar, A.; Gadgil, M.; McPake, B. Community health workers as influential health system actors and not “just another pair of hands”. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2021, 10, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, P.; Stephenson, R. Understanding users’ perspectives of barriers to maternal health care use in Maharashtra, India. J. Biosoc Sci. 2001, 33, 339–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawde, N.C.; Sivakami, M.; Babu, B.V. Utilization of maternal health services among internal migrants in Mumbai, India. J. Biosoc Sci. 2016, 48, 767–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bredesen, J.A. Women’s use of healthcare services and their perspective on healthcare utilization during pregnancy and childbirth in a small village in Northern India. Am. Int. J. Contemp. Res. 2013, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mahapatro, M. Equity in utilization of health care services: Perspective of pregnant women in southern Odisha, India. Indian J. Med. Res. 2015, 142, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Singh, A.; Sharma, V. Provider’s and user’s perspective about immunization coverage among migratory and non-migratory population in slums and construction sites of Chandigarh. J. Urban. Health 2015, 92, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Issac, A.; Rajbangshi, P.; Srivastava, A.; Avan, B.I. “Neither we are satisfied nor they”-users and provider’s perspective: A qualitative study of maternity care in secondary level public health facilities, Uttar Pradesh, India. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Firoz, T.; McCaw-Binns, A.; Filippi, V.; Magee, L.A.; Costa, M.L.; Cecatti, J.G.; Barreix, M.; Adanu, R.; Chou, D.; Say, L.; et al. A framework for healthcare interventions to address maternal morbidity. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 141, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santhya, K.G.; Prakash, R.; Jejeebhoy, S.J.; Singh, S.K. Accessing Adolescent Friendly Health Clinics in India: The Perspectives of Adolescents and Youth [Internet]; Population Council: New Delhi, India, 2014; Available online: https://www.popcouncil.org/uploads/pdfs/2014PGY_AFHC-IndiaReport.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2021).

- Hoopes, A.J.; Agarwal, P.; Bull, S.; Chandra-Mouli, V. Measuring adolescent friendly health services in India: A scoping review of evaluations. Reprod. Health 2016, 13, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yadav, R.J.; Mehta, R.; Pandey, A.; Adhikari, T. Evaluation of Adolescent-Friendly Health Services in India. Health Popul. Perspect. Issues 2009, 32, 66–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kohli, C.; Kishore, J.; Sharma, S.; Nayak, H. Knowledge and practice of Accredited Social Health Activists for maternal healthcare delivery in Delhi. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2015, 4, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, S. Role of ASHA, ANM & AWW health workers for development of pregnant women and children in India. Int. J. Adv. Res. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 81–117. [Google Scholar]

- Begum, S.; Sebastian, A.; Kulkarni, R.; Singh, S.; Donta, B. Traditional practices during pregnancy and childbirth among tribal women from Maharashtra: A review. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2017, 4, 882–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Withers, M.; Kharazmi, N.; Lim, E. Traditional beliefs and practices in pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum: A review of the evidence from Asian countries. Midwifery 2018, 56, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahariya, C. ‘Ayushman Bharat’program and universal health coverage in India. Indian Pediatrics 2018, 55, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Mehra, D.; Nayak, H.; Singh, M.M. Qualitative lens to assessing the ground level implementation of conditional cash transfer scheme in India. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 7, 2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Padmadas, S.S.; Mishra, U.S.; Pallikadavath, S.; Johnson, F.A.; Matthews, Z. Socio-Economic Inequalities in the Use of Postnatal Care in India. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gurnani, V.; Haldar, P.; Aggarwal, M.K.; Das, M.K.; Chauhan, A.; Murray, J.; Arora, N.K.; Jhalani, M.; Sudan, P. Improving vaccination coverage in India: Lessons from Intensified Mission Indradhanush, a cross-sectoral systems strengthening strategy. BMJ 2018, 7, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clarke-Deelder, E.; Suharlim, C.; Chatterjee, S.; Brenzel, L.; Ray, A.; Cohen, J.; McConnell, M.; Resch, S.; Menzies, N. Impact of campaign-style delivery of routine vaccines during Intensified Mission Indradhanush in India: A controlled interrupted time-series analysis. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, N.C. Hunger, under-nutrition and food security in India. In Poverty, Chronic Poverty and Poverty Dynamics; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 55–92. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar, S.; Aguayo, V.M.; Krishna, V.; Nair, R. Household food insecurity and children’s dietary diversity and nutrition in India. Evidence from the comprehensive nutrition survey in Maharashtra. Mater. Child Nutr. 2017, 13, e12447. [Google Scholar]

- George, N.A.; McKay, F.H. The public distribution system and food security in India. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gauri, V.; Rahman, T.; SEN, I.K. Shifting social norms to reduce open defecation in rural India. Behav. Public Policy 2018, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, S.; Kostizak, K.; Ramaiya, A.; Cronin, C. Measuring the effectiveness of communication programming on menstrual health and hygiene management (MHM) social norms among adolescent girls in India. Glob. Public Health 2021, 16, 578–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.R.; Montgomery, S.; Lee, J.W.; Anderson, B.A. Social and cultural factors associated with perinatal grief in Chhattisgarh, India. J. Community Health 2012, 37, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kennedy, E.; Stickland, J.; Kershaw, M.; Biadgilign, S. Impact of social and behavior change communication in nutrition specific interventions on selected indicators of nutritional status. J. Hum. Nutr. 2018, 2, 34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Mahanta, T.G.; Boruah, M.; Singh, V.K.; Gogoi, P.; Rane, T.; Mahanta, B.N. Effect of social and behavior change communication by using infotainment in community perception of adolescent girls for reproductive and sexual health care in high priority districts of Assam. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2016, 4, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).