Is Food Outlet Accessibility a Significant Factor of Fruit and Vegetable Intake? Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Province-Wide Study in Quebec, Canada

Abstract

1. Introduction

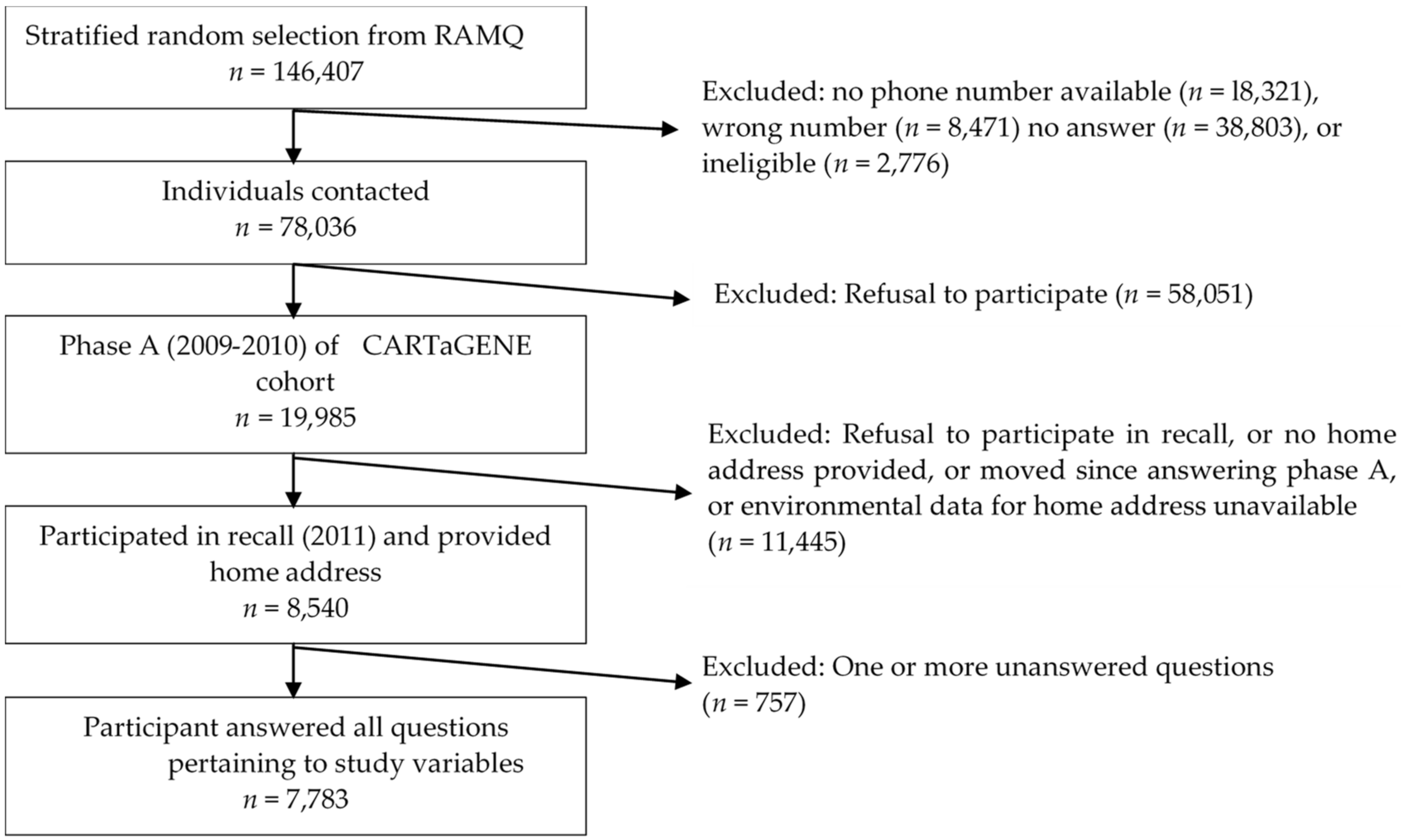

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Dependant Variable: Food Consumption Measure

2.3. Independent Variables: Retail Food Access Measure

2.4. Confounding Variables: Individual and Environmental Measures

2.5. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analyses

3.2. Univariate Analyses

3.3. Multivariate Analysis

4. Discussion

Limits and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic: Report of a WHO Consultation; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Health Fact Sheets; Overweight and Obese Adults, 2018. 2019. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/82-625-x/2019001/article/00005-eng.pdf?st=jwpIv0wd (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Government of Canada. Obesity in Canada—Health and Economic Implications 2011. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/healthy-living/obesity-canada/health-economic-implications.html (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Public Health Agency of Canada. The Chief Public Health Officer’s Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2017—Designing Healthy Living; Public Health Agency of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017.

- World Health Organization. Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases; Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United NATIONS. What is a Serving? 2003. Available online: http://www.fao.org/english/newsroom/focus/2003/fruitveg2.htm (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health; Promoting Fruit and Vegetable Consumption around the World (Information Sheet). Available online: https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/fruit/en/index2.html (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Statistics Canada. Table 13-10-0451-01, Health Indicators, Annual Estimates, 2003–2014. 2014. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310045101&pickMembers%5B0%5D=1.37&pickMembers%5B1%5D=2.1&pickMembers%5B2%5D=3.1&cubeTimeFrame.startYear=2010&cubeTimeFrame.endYear=2014&referencePeriods=20100101%2C20140101&request_locale=en (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Glanz, K.; Sallis, J.F.; Saelens, B.E.; Frank, L.D. Healthy nutrition environments: Concepts and measures. Am. J. Health Promot. 2005, 19, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanz, K. Measuring food environments: A historical perspective. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, S93–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamba, R.J.; Schuchter, J.; Rutt, C.; Seto, E.Y.W. Measuring the food environment and its effects on obesity in the United States: A Systematic review of methods and results. J. Community Health 2015, 40, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, A.M.; Horowitz, C.R. Best practices in policy approaches to obesity prevention. J. Health Care Poor Underserv. 2013, 24, 168–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robitaille, É.; Bergeron, P. Accessibilité Géographique aux Commerces Alimentaires au Québec: Analyse de Situation et Perspectives D’interventions; Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec: Québec, QC, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmanian Elham, E.; Gasevic, D.; Vukmirovich, I.; Lear, S.A. The association between the built environment and dietary intake—A systematic review. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 23, 183–196. [Google Scholar]

- Minaker, L.M.; Shuh, A.; Olstad, D.L.; Engler-Stringer, R.; Black, J.L.; Mah, C.L. Retail food environments research in Canada: A scoping review. Can. J. Public Health 2016, 107, ES4–ES13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeykoon Am Hasanthi, A.H.; Engler-Stringer, R.; Muhajarine, N. Health-related outcomes of new grocery store interventions: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 2236–2248. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, E.; Radley, D.; Morris, M.; Hobbs, M.; Christensen, A.; Marwa, W.L.; Morrin, A.; Griffiths, C. A systematic review employing the GeoFERN framework to examine methods, reporting quality and associations between the retail food environment and obesity. Health Place 2019, 57, 186–199. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb, L.K.; Appel, L.J.; Franco, M.; Jones-Smith, J.C.; Nur, A.; Anderson, C.A. The relationship of the local food environment with obesity: A systematic review of methods, study quality, and results. Obesity 2015, 23, 1331–1344, Erratum in Obesity 2015, 23, 2517–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler-Stringer, R.; Le, H.; Gerrard, A.; Muhajarine, N. The community and consumer food environment and children’s diet: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, C.L.; Luongo, G.; Hasdell, R.; Taylor, N.G.A.; Lo, B.K. A systematic review of the effect of retail food environment interventions on diet and health with a focus on the enabling role of public policies. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2019, 8, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, R.C.; Raskind, I.G.; Harris, D.M.; Gazmararian, J.A.; Kramer, M.; Haardörfer, R.; Kegler, M.C. The dietary impact of introducing new retailers of fruits and vegetables into a community: Results from a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 21, 981–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, A.C.; Brazeau, A.S.; Dasgupta, K.; Ross, N.A. Neighbourhood retail food outlet access, diet and body mass index in Canada: A systematic review. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. Res Policy Pract. 2019, 39, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clary, C.M.; Ramos, Y.; Shareck, M.; Kestens, Y. Should we use absolute or relative measures when assessing foodscape exposure in relation to fruit and vegetable intake? Evidence from a wide-scale Canadian study. Prev. Med. 2015, 71, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, H.; Law, J.; Quick, M. Identifying food deserts and swamps based on relative healthy food access: A spatio-temporal Bayesian approach. International journal of health geographics. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2015, 14, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, K.E.; Bentley, R.J.; Kavanagh, A.M. Fruit and vegetable purchasing and the relative density of healthy and unhealthy food stores: Evidence from an Australian multilevel study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2013, 67, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercille, G.; Richard, L.; Gauvin, L.; Kestens, Y.; Payette, H.; Daniel, M. Comparison of two indices of availability of fruits/vegetable and fast food outlets. J. Urban Health 2013, 90, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polsky, J.Y.; Moineddin, R.; Dunn, J.R.; Glazier, R.H.; Booth, G.L. Absolute and relative densities of fast-food versus other restaurants in relation to weight status: Does restaurant mix matter? Prev. Med. 2016, 82, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giskes, K.; van Lenthe, F.; Avendano-Pabon, M.; Brug, J. A systematic review of environmental factors and obesogenic dietary intakes among adults: Are we getting closer to understanding obesogenic environments? Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, e95–e106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Canada. Measuring the Food Environment in Canada. 2013. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/healthy-eating/nutrition-policy-reports/measuring-food-environment-canada.html (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Cummins, S.; Macintyre, S. Food environments and obesity—Neighbourhood or nation? Int. J. Epidemiol. 2006, 35, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadalla, P.; Boileau, C.; Payette, Y.; Idaghdour, Y.; Goulet, J.-P.; Knoppers, B.; Hamet, P.; Laberge, C. Cohort profile of the CARTaGENE study: Quebec’s population-based biobank for public health and personalized genomics. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 42, 1285–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. 2016 Census Profile of Montreal, Quebec, Sherbrooke and Saguenay [Census Metropolitan Area], Quebec and Canada [Country]. Ottawa. 2017. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Lalonde, B.; Robitaille, É. L’environnement Bâti Autour des Écoles et les Habitudes de vie les Jeunes; État des Connaissances et Portrait du Québec.: Government of Quebec. 2014. Available online: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/pdf/publications/1894_Environnement_Bati_Ecoles.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Robitaille, É.; Paquette, M.C. Development of a method to locate deserts and food swamps following the experience of a region in Quebec, Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahendra, A.; Polsky, J.Y.; Robitaille, E.; Lefebvre, M.; McBrien, T.; Minaker, L.M. Geographic retail food environment measures for use in public health. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. Res. Policy Pract. 2017, 37, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. Dissemination Area (DA); Plain Language Definition 2018. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/92-195-x/2011001/geo/da-ad/da-ad-eng.htm (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Census Tract Level State Maps of the Modified Retail Food Environment Index (mRFEI). 2011. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/downloads/census-tract-level-state-maps-mrfei_TAG508.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Gamache, P.; Hamel, D.; Blasser, C. Material and Social Deprivation Index: A Summary. Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec. 2019. Available online: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/sites/default/files/santescope/indice-defavorisation/en/GuideMethodologiqueEN.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Kullberg, K.; Aberg, A.C.; Bjorklund, A.; Ekblad, J.; Sidenvall, B. Daily eating events among co-living and single-living, diseased older men. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2008, 12, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremmer, D.; Anderson, A.S.; Marshall, D.W. Living together and eating together: Changes in food choice and eating habits during the transition from single to married/cohabiting. Sociol. Rev. 1998, 46, 48–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, 25th ed.; IBM: Armonk, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenbach, J.D.; Beenackers, M.A.; Noordzij, J.M.; Groeniger, J.O.; Lakerveld, J.; van Lenthe, F.J. The moderating role of self-control and financial strain in the relation between exposure to the food environment and obesity: The GLOBE Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenbach, J.D.; Rutter, H.; Compernolle, S.; Glonti, K.; Oppert, J.-M.; Charreire, H.; de Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Brug, J.; Nijpels, G.; Lakerveld, J. Obesogenic environments: A systematic review of the association between the physical environment and adult weight status, the SPOTLIGHT project. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assari, S.; Lankarani, M.M. Educational attainment promotes fruit and vegetable intake for Whites but not Blacks. J 2018, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plante, C.; Blanchet, C.; Rochette, L. La Consommation des Aliments Chez les Québécois Selon les Recommandations du Guide Alimentaire Canadien. Québec: Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec. 2019. Available online: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/sites/default/files/publications/2616_consommation_aliments_quebecois_guide_alimentaire.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Burgoine, T.; Mackenbach, J.D.; Lakerveld, J.; Forouhi, N.G.; Griffin, S.J.; Brage, S.; Wareham, N.J.; Monsivais, P. Interplay of socioeconomic status and supermarket distance is associated with excess obesity risk: A UK cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenk, S.N.; Lachance, L.L.; Schulz, A.J.; Mentz, G.; Kannan, S.; Ridella, W. Neighborhood retail food environment and fruit and vegetable intake in a multiethnic urban population. Am. J. Health Promot. 2009, 23, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.Y.; Paquet, C.; Dubé, L.; Nielsen, D.E. Diet quality and food prices modify associations between genetic susceptibility to obesity and adiposity outcomes. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, D.E.; Han, Y.; Paquet, C.; Portella, A.K.; Ma, Y.; Dube, L. Interaction of DRD2/ANKK1 Taq1A genotype with in-store retail food environment exposures on diet quality in a cohort of Quebec adults. Lifestyle Genom. 2020, 13, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodor, J.N.; Ulmer, V.M.; Dunaway, L.F.; Farley, T.A.; Rose, D. The rationale behind small food store interventions in low-income urban neighborhoods: Insights from New Orleans. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 1185–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enzenbach, C.; Wicklein, B.; Wirkner, K.; Loeffler, M. Evaluating selection bias in a population-based cohort study with low baseline participation: The LIFE-Adult-Study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandhagen, E.; Berg, C.; Lissner, L.; Nunez, L.; Rosengren, A.; Torén, K.; Thelle, D. Selection bias in a population survey with registry linkage: Potential effect on socioeconomic gradient in cardiovascular risk. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 25, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Reedy, J.; Butler, E.N.; Dodd, K.W.; Subar, A.F.; Thompson, F.E.; McKinnon, R.A. Dietary assessment in food environment research: A systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 46, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perchoux, C.; Chaix, B.; Cummins, S.; Kestens, Y. Conceptualization and measurement of environmental exposure in epidemiology: Accounting for activity space related to daily mobility. Health Place 2013, 21, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kestens, Y.; Thierry, B.; Shareck, M.; Steinmetz-Wood, M.; Chaix, B. Integrating activity spaces in health research: Comparing the VERITAS activity space questionnaire with 7-day GPS tracking and prompted recall. Spat. Spatio-Temporal Epidemiol. 2018, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chum, A.; Farrell, E.; Vaivada, T.; Labetski, A.; Bohnert, A.; Selvaratnam, I.; Larsen, K.; Pinter, T.; O’Campo, P. The effect of food environments on fruit and vegetable intake as modified by time spent at home: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e006200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Bianchi, F.; Piernas, C.; Payne Riches, S.; Frie, K.; Nourse, R.; Jebb, S.A. Grocery store interventions to change food purchasing behaviors: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 107, 1004–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalbert-Arsenault, E.; Robitaille, E.; Paquette, M.C. Development, reliability and use of a food environment assessment tool in supermarkets of four neighbourhoods in Montreal, Canada. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. Res Policy Pract. 2017, 37, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| Characteristics | Participants with Complete Data (n = 7783) % or Mean (SD) | Participants Who Were Excluded after Completing Phase A Survey % or Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 54.7 (7.7) | 54.0 (8.0) |

| Sex | n = 12,203 | |

| Men | 48.3 | 48.5 |

| Women | 51.7 | 51.5 |

| Annual household income | n = 10,883 | |

| Less than 25,000$ | 8.7 | 16.4 |

| 25,000$–49,999$ | 22.0 | 24.3 |

| 50,000$–74,999$ | 23.3 | 20.6 |

| 75,000$–99,999$ | 16.3 | 13.7 |

| 100,000$–149,999$ | 18.5 | 15.1 |

| More than 150,000$ | 11.3 | 9.9 |

| Education | n = 12,075 | |

| High school or less | 22.2 | 28.6 |

| Trade or technical school | 21.5 | 21.9 |

| Pre-university CEGEP 1 or non-university certificate | 10.1 | 10.0 |

| University certificate | 8.5 | 8.0 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 23.9 | 19.9 |

| Graduate studies | 13.7 | 11.5 |

| Marital status | n = 12,073 | |

| Married and/or living with a partner | 67.5 | 61.3 |

| Divorced, separated, widowed, or single | 32.5 | 38.7 |

| Employment situation | n = 12,046 | |

| Worker | 67.1 | 64.5 |

| Unemployed, unable to work, retired, or caregiver | 32.9 | 35.5 |

| Density of neighborhood of primary residence 2 | n = 1853 | |

| 1st and 2nd quintile—low density | 8.9 | 11.3 |

| 3rd quintile | 11.4 | 13.1 |

| 4th quintile | 29.6 | 26.3 |

| 5th quintile—high density | 50.2 | 49.3 |

| Material deprivation index of primary residence neighborhood | n = 1485 | |

| 1st quintile—most privileged | 31.7 | 37.6 |

| 2nd quintile | 23.7 | 21.5 |

| 3rd quintile | 19.7 | 18.2 |

| 4th quintile | 15.8 | 12.7 |

| 5th quintile—most deprived | 9.2 | 10.1 |

| Recommended F&V consumption | n = 11,779 | |

| No (0 to 4 portions per day) | 46.1 | 50.4 |

| Yes (5 or more portions per day) | 53.9 | 49.6 |

| Fruit and vegetable intake per day (number of portions) | n = 11,779 | |

| 5.0 (2.6) | 4.8 (2.6) |

| Characteristics | Individual Models OR (95% CI) | Model A 1 OR (95% CI) | Model B 2 OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Men | REF 3 | REF | REF |

| Women | 2.88 (2.63–3.16) ** | 3.13 (2.85–3.44) ** | 3.13 (2.85–3.44) ** |

| Age | |||

| 1st quintile: Age 40.1–46.5 | REF | ||

| 2nd quintile: Age 46.6–51.1 | 1.04 (0.89–1.20) | ||

| 3rd quintile: Age 51.2–55.7 | 1.05 (0.91–1.22) | ||

| 4th quintile: Age 55.8–62.3 | 1.03 (0.89–1.19) | ||

| 5th quintile: Age 62.4–70.3 | 1.08 (0.93–1.25) | ||

| Annual household income | |||

| Less than 25,000$ | REF | REF | REF |

| 25,000$–49,999$ | 1.12 (0.94–1.34) | 1.14 (0.95–1.37) | 1.14 (0.94–1.37) |

| 50,000$–74,999$ | 1.30 (1.09–1.55) ** | 1.32 (1.09–1.59) ** | 1.32 (1.09–1.59) ** |

| 75,000$–99,999$ | 1.28 (1.06–1.54) * | 1.31 (1.07–1.60) ** | 1.31 (1.07–1.60) ** |

| 100,000$–149,999$ | 1.42 (1.18–1.71) ** | 1.41 (1.16–1.72) ** | 1.40 (1.15–1.71) ** |

| More than 150,000$ | 1.75 (1.42–2.14) ** | 1.59 (1.28–1.99) ** | 1.57 (1.25–1.96) ** |

| Education | |||

| High school or less | REF | REF | REF |

| Trade or technical school | 1.27 (1.11–1.45) ** | 1.27 (1.11–1.47) ** | 1.27 (1.10–1.46) ** |

| Pre-university CEGEP 2 or non-university certificate | 1.53 (1.29–1.81) ** | 1.51 (1.26–1.80) ** | 1.50 (1.25–1.79) ** |

| University certificate | 1.66 (1.38–1.99) ** | 1.63 (1.35–1.97) ** | 1.62 (1.34–1.96) ** |

| Bachelor’s degree | 1.79 (1.56–2.04) ** | 1.80 (1.56–2.07) ** | 1.77 (1.53–2.04) ** |

| Graduate studies | 2.08 (1.78–2.43) ** | 2.20 (1.85–2.61) ** | 2.16 (1.82–2.57) ** |

| Marital status | |||

| Married and/or living with a partner | REF | ||

| Divorced, separated, widowed, or single | 0.98 (0.89–1.08) | ||

| Employment situation | |||

| Worker | REF | ||

| Unemployed, unable to work, retired, or care giver | 1.00 (0.91–1.10) | ||

| Density of neighborhood of primary residence | |||

| 1st and 2nd quintile—low density | REF | ||

| 3rd quintile | 0.98 (0.80–1.19) | ||

| 4th quintile | 1.03 (0.87–1.22) | ||

| 5th quintile—high density | 1.14 (0.97–1.34) | ||

| Material deprivation index of primary residence neighborhood | |||

| 1st quintile—most privileged | REF | REF | |

| 2nd quintile | 0.91 (0.81–1.03) | 1.00 (0.88–1.14) | |

| 3rd quintile | 0.75 (0.66–0.86) ** | 0.85 (0.74–0.98) * | |

| 4th quintile | 0.79 (0.69–0.91) ** | 0.93 (0.80–1.08) | |

| 5th quintile—most deprived | 0.79 (0.67–0.93) ** | 0.99 (0.82–1.18) | |

| Proximity to nearest retail food outlet 4 | |||

| 1st quintile: 0–391 (Near) | REF | ||

| 2nd quintile: 392–694 | 0.91 (0.79–1.05) | ||

| 3rd quintile: 695–1102 | 0.84 (0.73–0.97) * | ||

| 4th quintile: 1103–1705 | 0.85 (0.74–0.98) * | ||

| 5th quintile: 1706–13865 (Far) | 0.90 (0.78–1.04) | ||

| Proximity to the nearest convenience store | |||

| 1st quintile: 0–248 (Near) | REF | ||

| 2nd quintile: 248–441 | 0.76 (0.66–0.88) ** | ||

| 3rd quintile: 441–674 | 0.84 (0.72–0.96) * | ||

| 4th quintile: 674–1064 | 0.87 (0.75–1.00) * | ||

| 5th quintile: 1065–6786 (Far) | 0.78 (0.68–0.90) ** | ||

| Proximity to nearest fast food outlet | |||

| 1st quintile: 0–377 (Near) | REF | ||

| 2nd quintile: 377–613 | 0.89 (0.77–1.03) | ||

| 3rd quintile: 613–915 | 0.91 (0.79–1.05) | ||

| 4th quintile: 916–1394 | 0.81 (0.70–0.93) ** | ||

| 5th quintile: 1395–14461 (Far) | 0.85 (0.74–0.98) * | ||

| Density of retail food outlets 4 | |||

| 1st quintile: 0.00–0.06 | REF | ||

| 2nd quintile: 0.07–1.00 | 0.90 (0.79–1.03) | ||

| 3rd quintile: 1.002–2.32 | 0.915 (0.79–1.06) | ||

| 4th quintile: 2.33–6.00 | 0.98 (0.85–1.13) | ||

| 5th quintile: 6.01–37.97 | 1.22 (1.05–1.40) ** | ||

| Density of convenience stores | |||

| 1st quintile: 0.00 -1.31 | REF | ||

| 2nd quintile: 1.31–3.00 | 1.00 (0.87–1.15) | ||

| 3rd quintile: 3.00–6.00 | 1.14 (0.99–1.31) | ||

| 4th quintile: 6.04–13.52 | 1.08 (0.94–1.25) | ||

| 5th quintile: 13.53–60.60 | 1.27 (1.11–1.47) ** | ||

| Density of fast food outlet | |||

| 1st quintile: 0.00–0.76 | REF | ||

| 2nd quintile: 0.76–2.73 | 0.93 (0.81–1.07) | ||

| 3rd quintile: 2.73–5.71 | 1.00 (0.87–1.15) | ||

| 4th quintile: 5.72–11.58 | 1.00 (0.87–1.15) | ||

| 5th quintile: 11.60–213.15 | 1.24 (1.07–1.43) ** | ||

| Relative density of less healthy outlets (mRFEI 5) | |||

| 1st quintile: 0–75% | REF | ||

| 2nd quintile: 75–81% | 1.00 (0.86–1.15) | ||

| 3rd quintile: 81–87% | 0.95 (0.82–1.09) | ||

| 4th quintile: 87–95% | 0.86 (0.75–0.99) * | ||

| 5th quintile: 95–100% | 0.95 (0.83–1.10) | ||

| X2 (p-value) | 712.1 (0.00) | 719.1 (0.00) | |

| Cox & Snell R Square | 0.087 | 0.088 | |

| Nagelkerke R Square | 0.117 | 0.118 | |

| Percentage accuracy in classification (PAC) | 63.7% | 63.8% |

| Characteristics | Models 1 OR (95% CI) | X2 (p-Value) | Cox & Snell R Square | Nagelkerke R Square |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proximity to nearest retail food outlet 1 | 747.26 | 0.09 | 0.122 | |

| 1st quintile: 0–391 (Near) | REF 2 | |||

| 2nd quintile: 392–694 | 0.91 (0.78–1.06) | |||

| 3rd quintile: 695–1102 | 0.87 (0.74–1.02) | |||

| 4th quintile: 1103–1705 | 0.89 (0.76–1.05) | |||

| 5th quintile: 1706–13,865 (Far) | 0.97 (0.81–1.16) | |||

| Proximity to the nearest convenience store | 747.15 | 0.09 | 0.123 | |

| 1st quintile: 0–248 (Near) | REF | |||

| 2nd quintile: 248–441 | 0.82 (0.70–0.95) * | |||

| 3rd quintile: 441–674 | 0.84 (0.71–0.98) * | |||

| 4th quintile: 674–1064 | 0.85 (0.71–1.01) | |||

| 5th quintile: 1065–6786 (Far) | 0.76 (0.63–0.91) * | |||

| Proximity to nearest fast food outlet | 753.83 | 0.09 | 0.123 | |

| 1st quintile: 0–377 (Near) | REF | |||

| 2nd quintile: 377–613 | 0.89 (0.76–1.04) | |||

| 3rd quintile: 613–915 | 0.92 (0.79–1.08 | |||

| 4th quintile: 916–1394 | 0.80 (0.68–0.93) * | |||

| 5th quintile: 1395–14,461 (Far) | 0.86 (0.72–1.02) | |||

| Density of retail food outlets | 751.96 | 0.09 | 0.123 | |

| 1st quintile: 0.00–0.06 | REF | |||

| 2nd quintile: 0.07–1.00 | 0.91 (0.79–1.05) | |||

| 3rd quintile: 1.002–2.32 | 0.90 (0.77–1.06) | |||

| 4th quintile: 2.33–6.00 | 0.95 (0.81–1.12) | |||

| 5th quintile: 6.01–37.97 | 1.12 (0.94–1.33) | |||

| Density of convenience stores | 754.90 | 0.09 | 0.124 | |

| 1st quintile: 0.00–1.31 | REF | |||

| 2nd quintile: 1.31–3.00 | 1.07 (0.92–1.25) | |||

| 3rd quintile: 3.00–6.00 | 1.22 (1.03–1.43) * | |||

| 4th quintile: 6.04–13.52 | 1.15 (0.97–1.38) | |||

| 5th quintile: 13.53–60.60 | 1.35 (1.12–1.62) ** | |||

| Density of fast food outlet | 749.76 | 0.09 | 0.123 | |

| 1st quintile: 0.00–0.76 | REF | |||

| 2nd quintile: 0.76–2.73 | 0.92 (0.79–1.07) | |||

| 3rd quintile: 2.73–5.71 | 0.99 (0.85–1.16) | |||

| 4th quintile: 5.72–11.58 | 0.99 (0.85–1.17) | |||

| 5th quintile: 11.60–213.15 | 1.13 (0.95–1.34) | |||

| Relative density of less healthy outlets (mRFEI 3) | 747.15 | 0.09 | 0.122 | |

| 1st quintile: 0–75% | REF | |||

| 2nd quintile: 75–81% | 1.02 (0.88–1.19) | |||

| 3rd quintile: 81–87% | 0.98 (0.84–1.14) | |||

| 4th quintile: 87–95% | 0.91 (0.78–1.05) | |||

| 5th quintile: 95–100% | 1.05 (0.90–1.22) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mathieu, A.-A.; Robitaille, É.; Paquette, M.-C. Is Food Outlet Accessibility a Significant Factor of Fruit and Vegetable Intake? Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Province-Wide Study in Quebec, Canada. Obesities 2022, 2, 35-50. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities2010004

Mathieu A-A, Robitaille É, Paquette M-C. Is Food Outlet Accessibility a Significant Factor of Fruit and Vegetable Intake? Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Province-Wide Study in Quebec, Canada. Obesities. 2022; 2(1):35-50. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities2010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleMathieu, Alex-Ane, Éric Robitaille, and Marie-Claude Paquette. 2022. "Is Food Outlet Accessibility a Significant Factor of Fruit and Vegetable Intake? Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Province-Wide Study in Quebec, Canada" Obesities 2, no. 1: 35-50. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities2010004

APA StyleMathieu, A.-A., Robitaille, É., & Paquette, M.-C. (2022). Is Food Outlet Accessibility a Significant Factor of Fruit and Vegetable Intake? Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Province-Wide Study in Quebec, Canada. Obesities, 2(1), 35-50. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities2010004