Decentralized Hydrogen Production from Magnesium Hydrolysis for Off-Grid Residential Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Hydrogen Generation by Hydrolysis with Magnesium

- -

- Raising the water temperature to improve the hydrolysis rate of Mg;

- -

- Incorporating additives during hydrolysis, such as ion exchangers or buffering agents, to postpone the development of the passive layer (Mg(OH)2);

- -

- Employing both doping additives and mechanical grinding to exfoliate the hydroxide layer, thereby generating multiple surface defects.

- -

- an increase in reaction rate (two to three times);

- -

- reduction of full hydrolysis time from >20 min to 6–7 min;

- -

- an increase in conversion ratio from ≈60–70% (raw Mg) to >95%;

- -

- improved resistance to passivation due to exfoliation of Mg(OH)2.

- -

- Large Mg particles (>200 μm) suffer from incomplete conversion because diffusion is limited once a passivating Mg(OH)2 shell forms [20].

- -

- Small particles (<50 μm) indeed yield faster kinetics but introduce safety concerns related to dust explosivity when handled in air.

- -

- inert N2 storage;

- -

- automated feeding;

- -

- reduced oxygen exposure;

- -

- a wet reaction environment that eliminates dust-ignition risk.

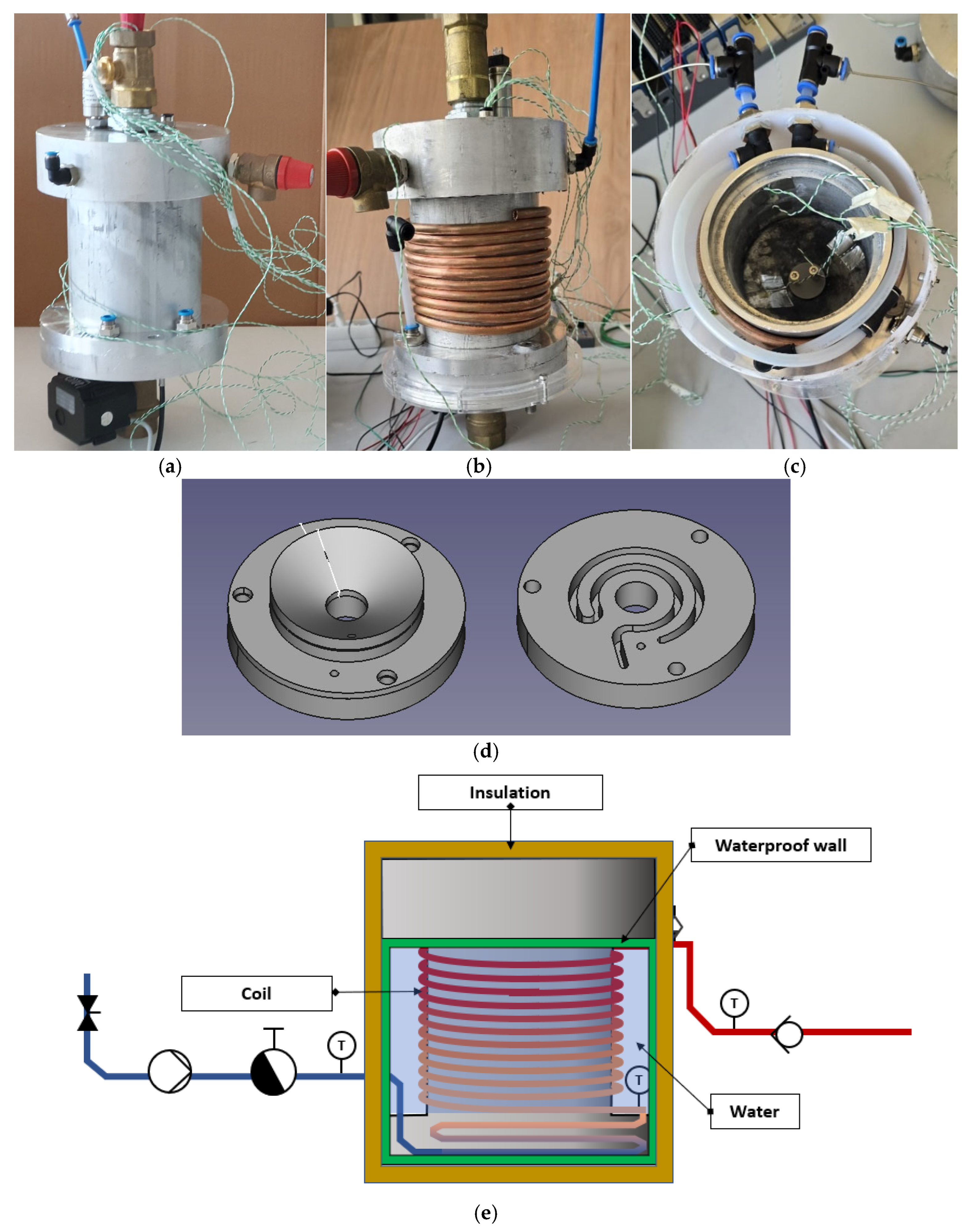

- 1-

- Insertion of the magnesium powder (approximately 20 g) through the top motorized valve;

- 2-

- Gradual injection of water to maintain the pressure inside the reactor at 2 bar and, thus, produce hydrogen on demand;

- 3-

- At the end of the reaction (evaluated using a hydrogen flow meter), ejection of the reaction products through the bottom motorized valve and rinsing of the reactor;

- 4-

- Return to step 1.

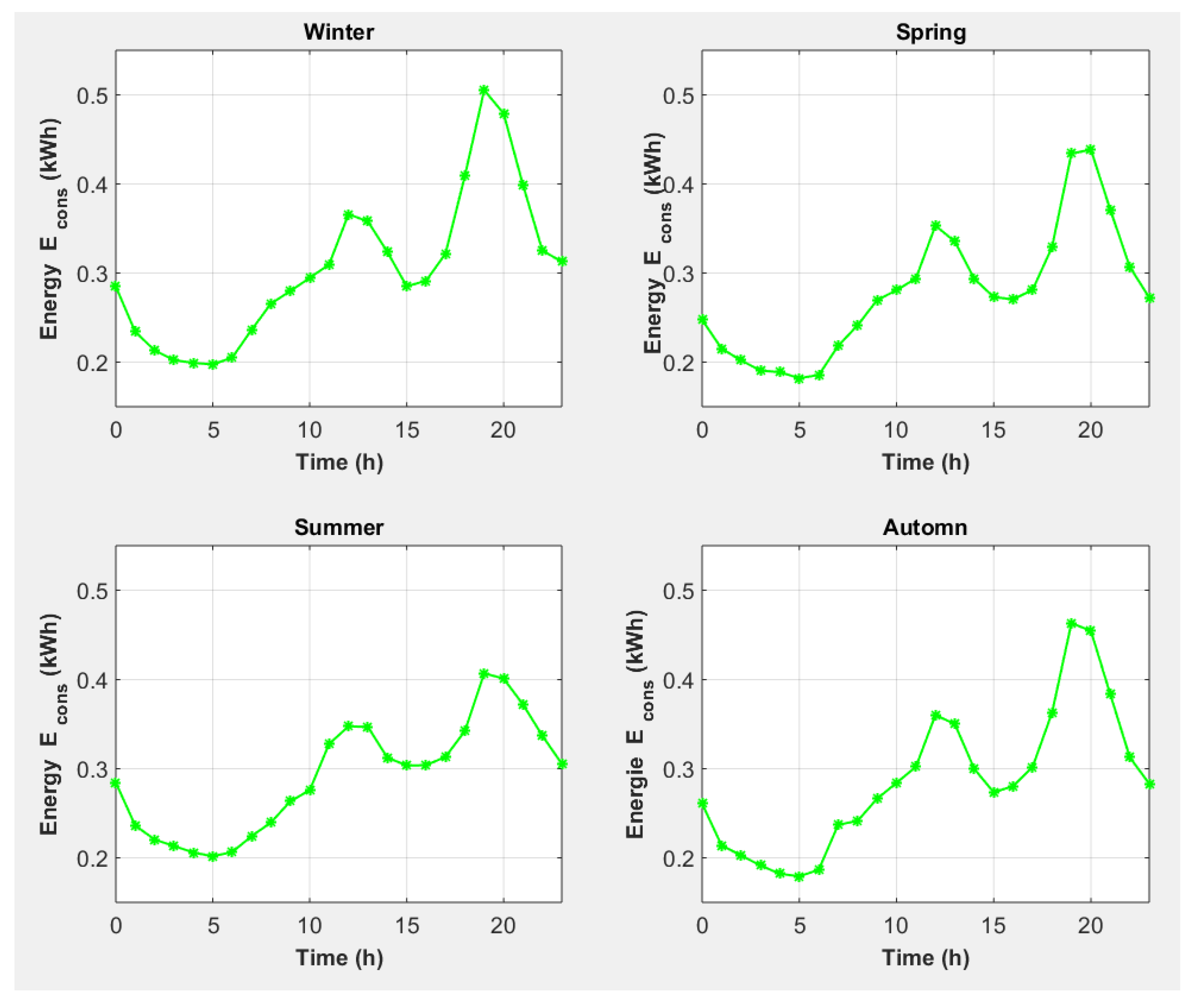

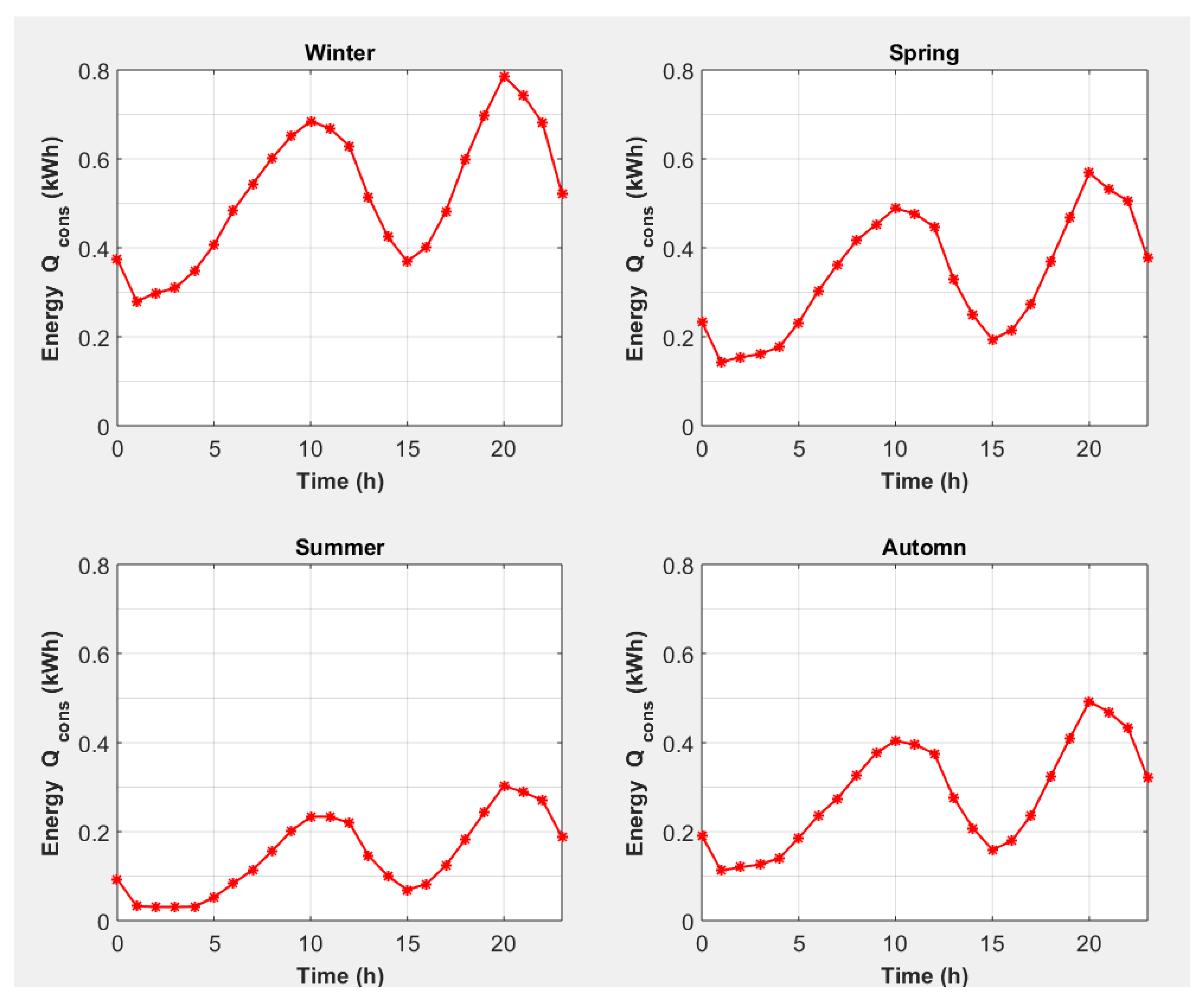

3. Study Case

- -

- -

- -

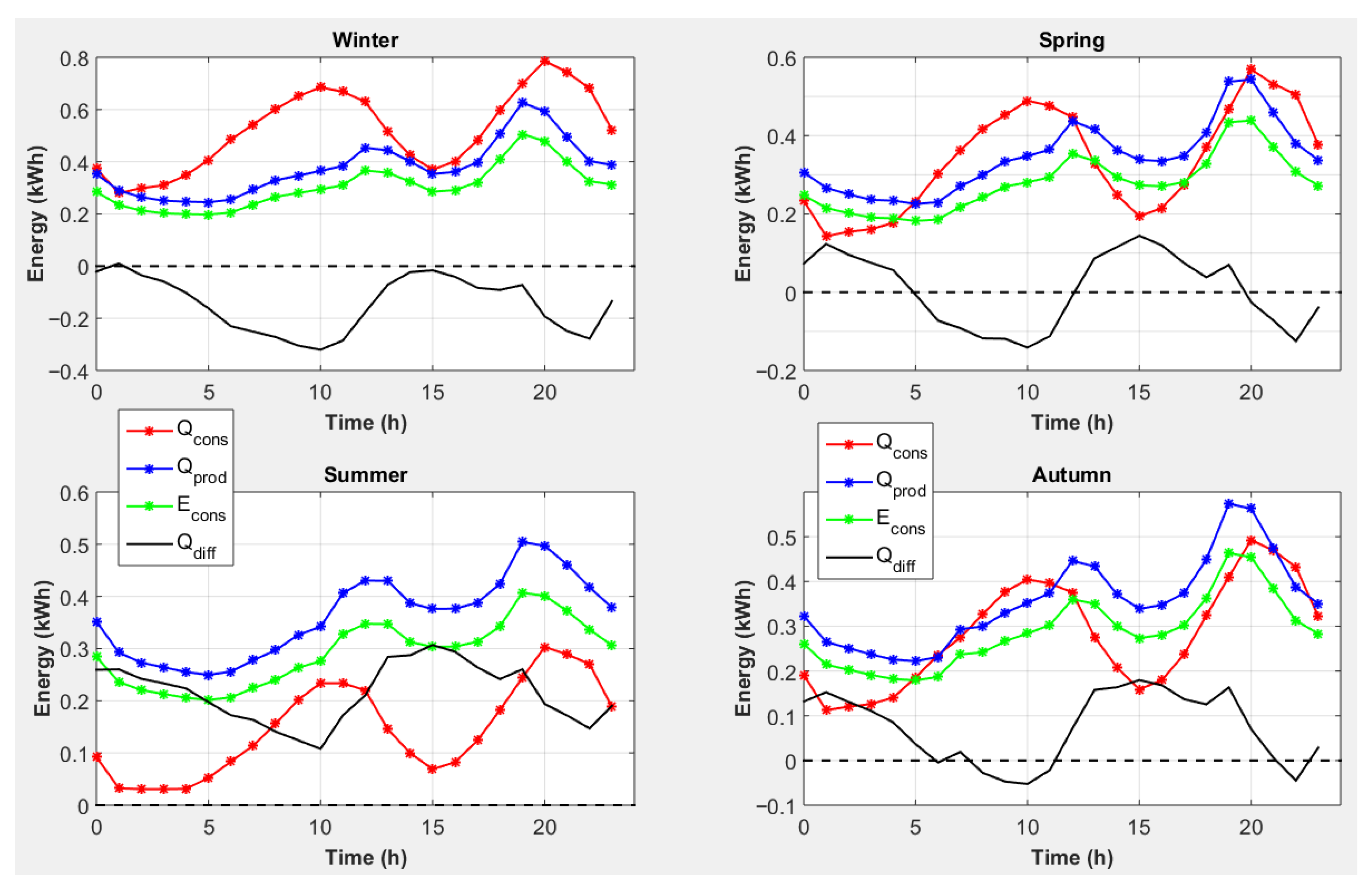

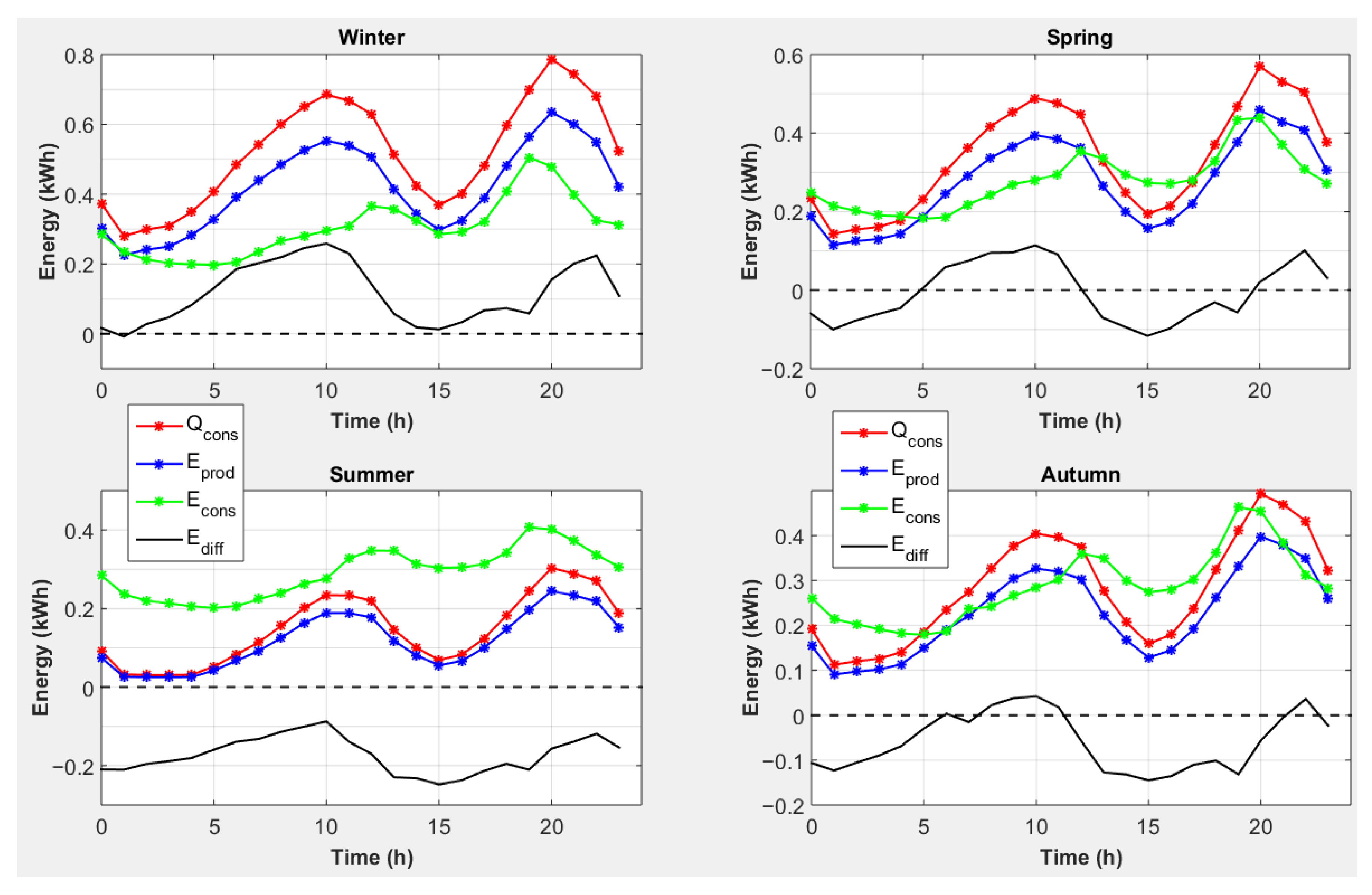

4. Evaluation of Magnesium Consumption According to Several Strategies

- -

- Density of hydrogen: ;

- -

- Density of magnesium: ;

- -

- Mass of hydrogen produced by the hydrolysis of magnesium with 100% conversion efficiency: ;

- -

- Chemical energy of hydrogen: ;

- -

- Heat produced by the reaction at 298 K: ;

- -

- Hydrolysis reaction efficiency: ;

- -

- PEMFC and DC/AC converter efficiency [16]: ;

- -

- DC/AC converter efficiency [33]: ;

- -

- Heat exchanger efficiency [34]: .

- -

- Mass of hydrogen produced: ;

- -

- Chemical energy produced: /kg;

- -

- Electrical energy produced: ;

- -

- Heat energy produced: .

4.1. Strategy 1: Magnesium Consumption to Cover Electrical Needs

4.2. Strategy 2: Magnesium Consumption to Cover Heat Needs

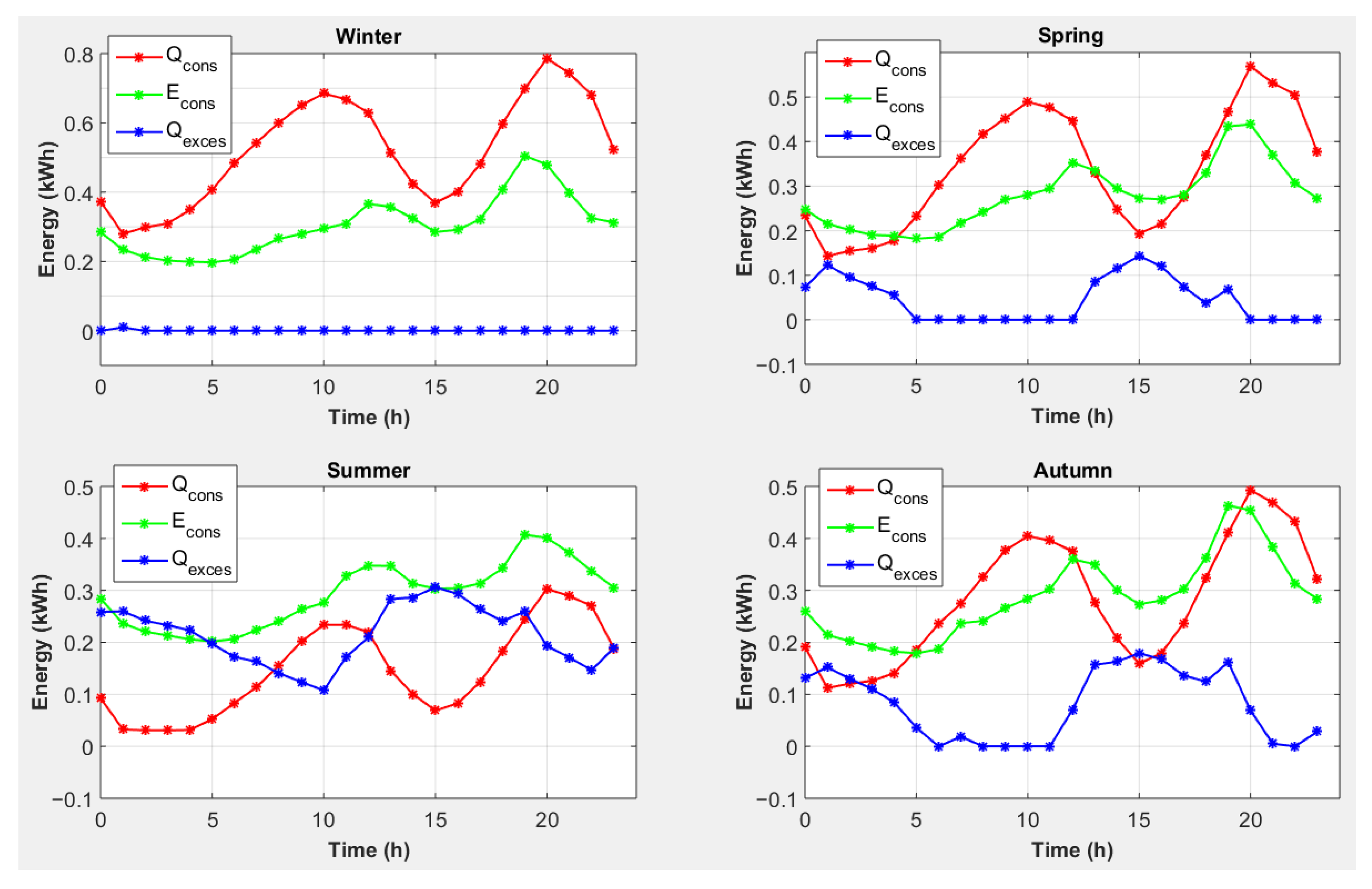

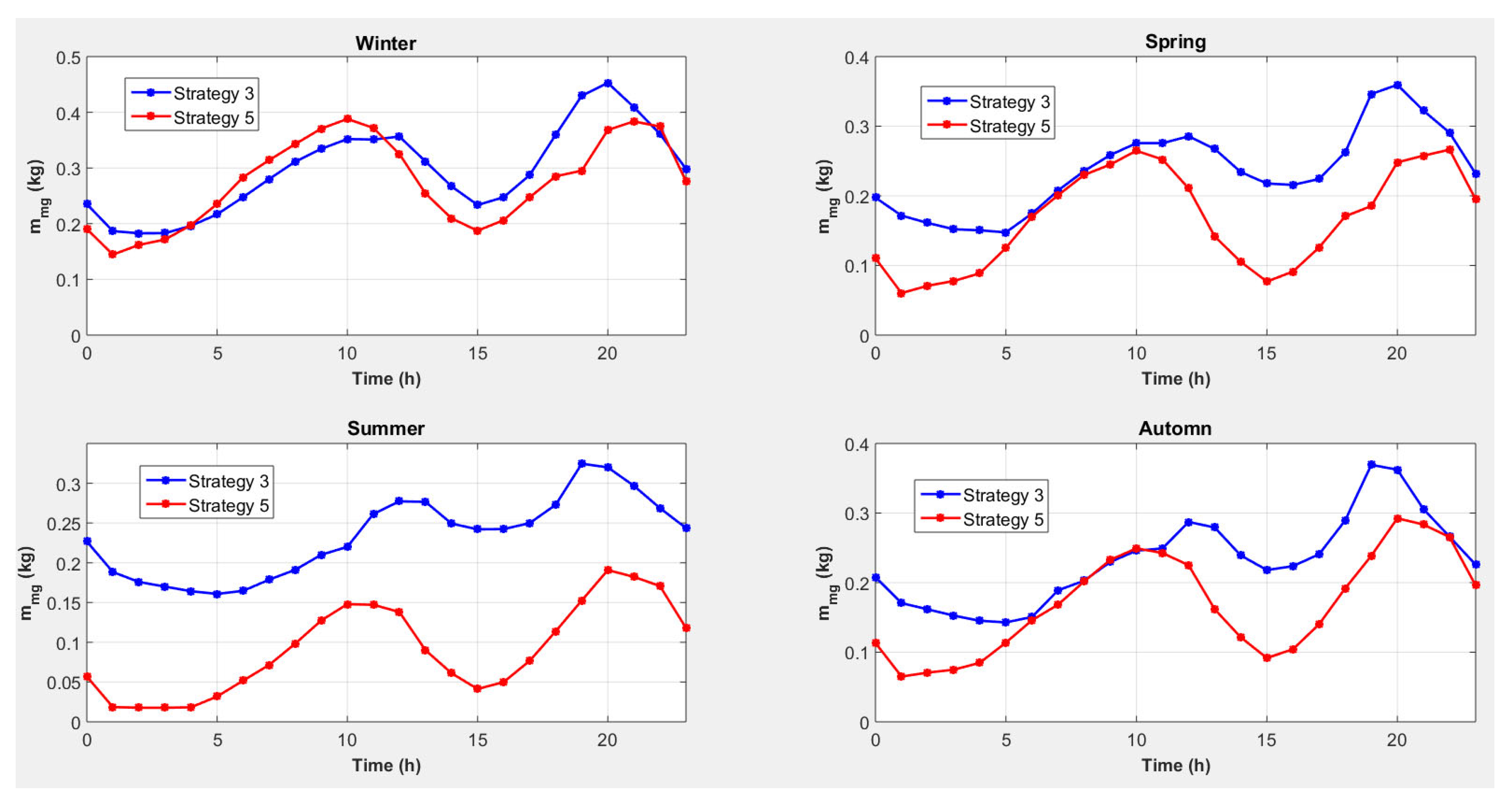

4.3. Strategy 3: Magnesium Consumption to Cover Heat Needs with Conversion of Excess Electricity into Heat

4.4. Strategy 4: Magnesium Consumption to Cover Heat Needs with Conversion of Excess Heat and Electricity

- -

- part of the electricity, denoted , is converted into heat with an efficiency in case of excess electricity;

- -

- part of the heat, denoted , is converted into electricity with an efficiency in case of excess heat.

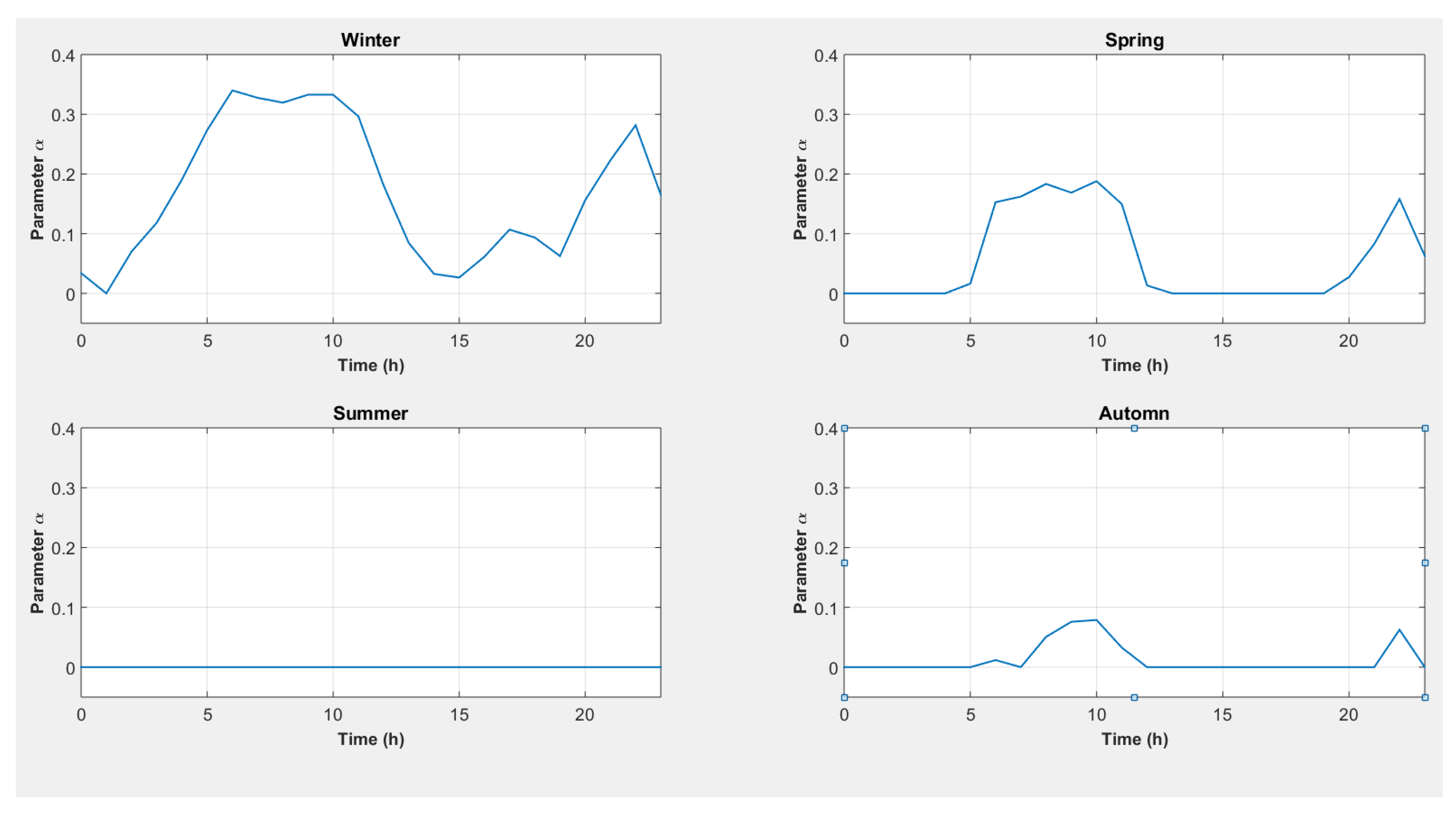

- 1-

- A vector of 1000 values of is created with .

- 2-

- For each season, each hour, and each value of system (20) is solved, and the values of are computed using the relation:

- 3-

- If , then the corresponding values of are computed using

- 4-

- If (the case does not occur) then is set to 1 in Equation (20), and the values of and are computed using

- 5-

- For a season and a time slot, this resolution can produce several possible values of and which cover heat and electricity needs (due to parameter gridding). Those that lead to the minimum value of are then retained.

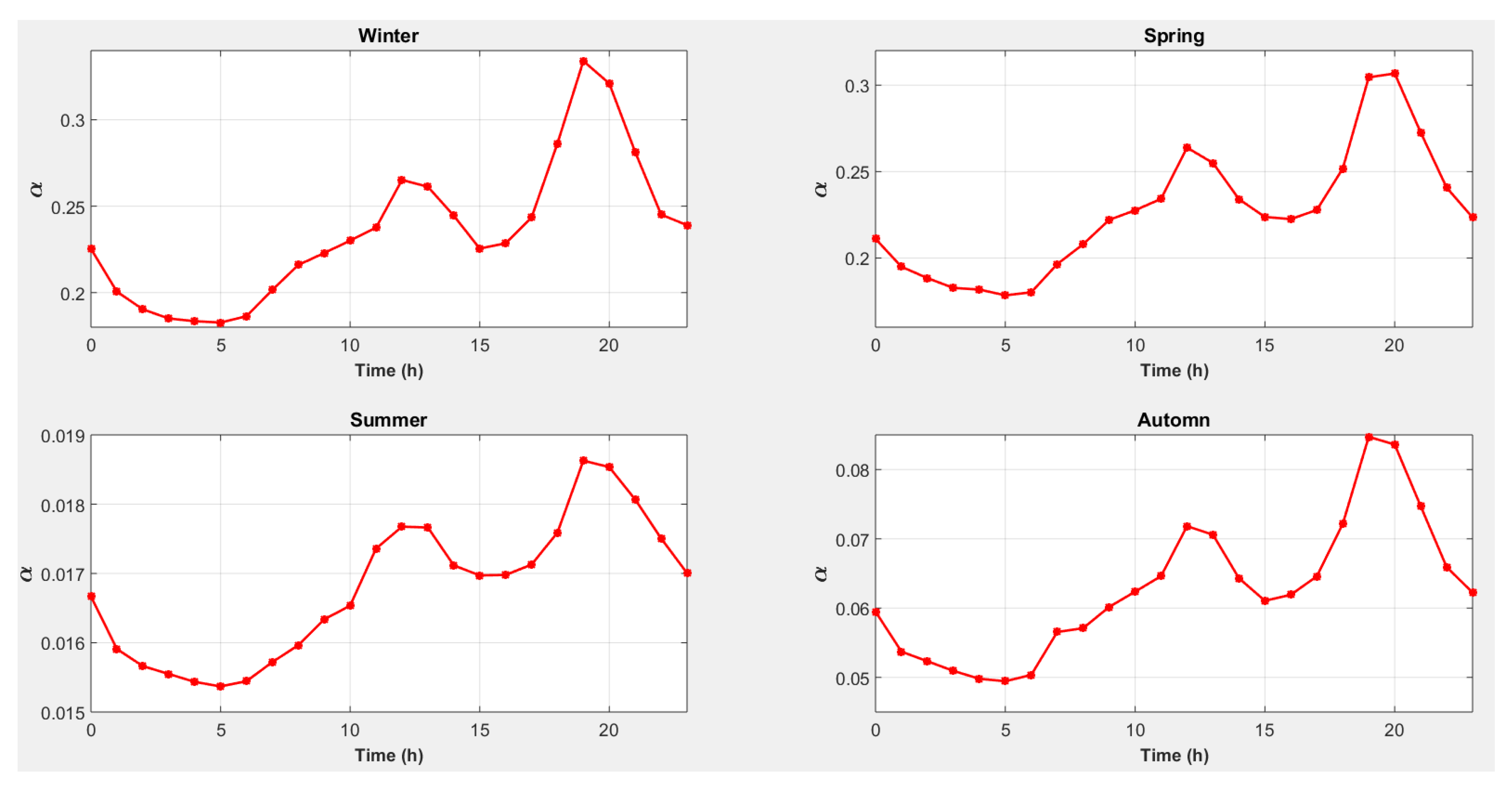

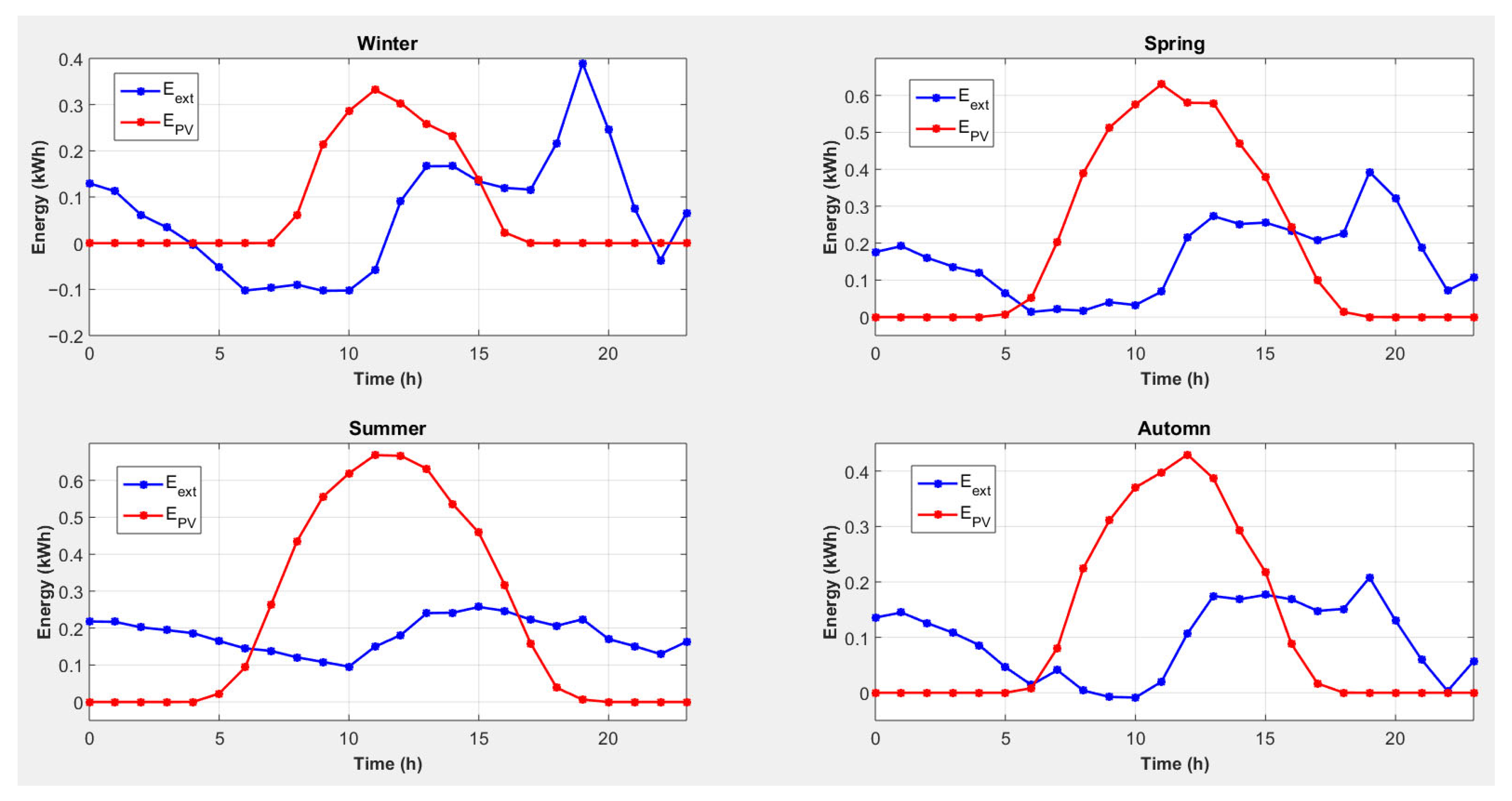

4.5. Strategy 5: Magnesium Consumption to Cover Heat Needs with Conversion of Excess Electricity into Heat and an External Electrical Energy Source

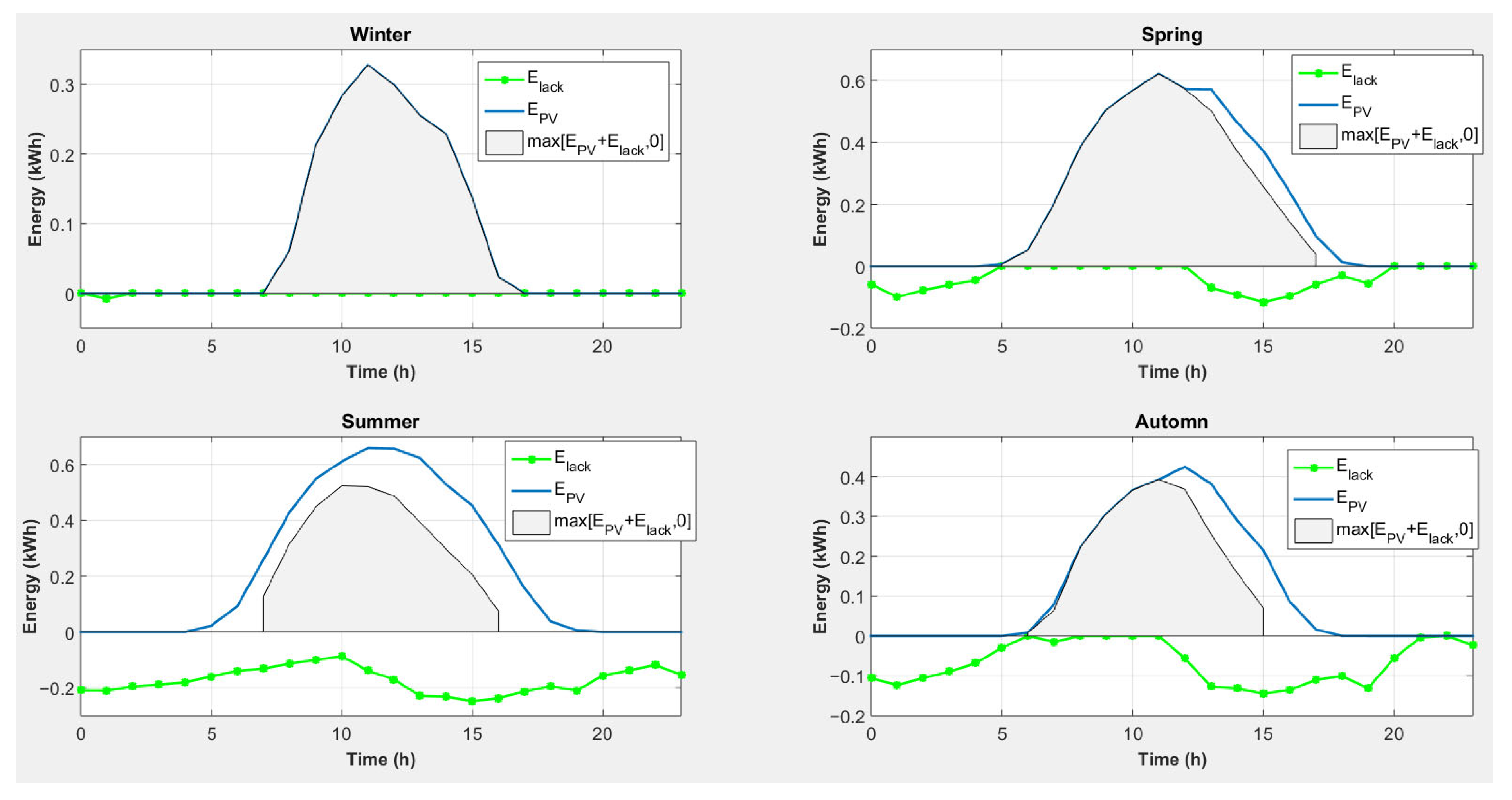

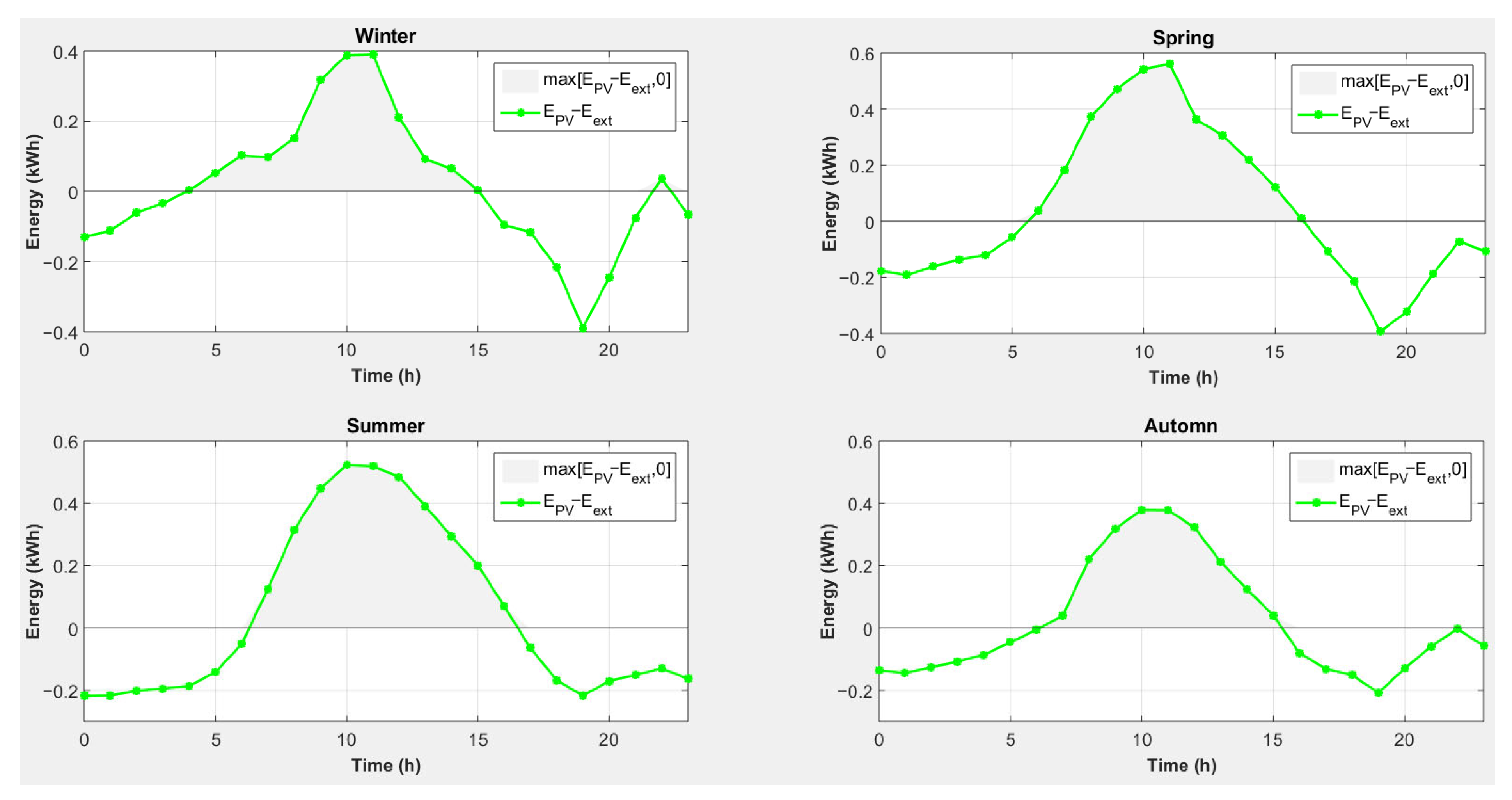

- -

- For all seasons, photovoltaic production will cover the electricity shortage caused by the use of magnesium to cover heating needs, and there is even an excess of electricity.

- -

- Photovoltaic energy production is not synchronized with the lack of electricity.

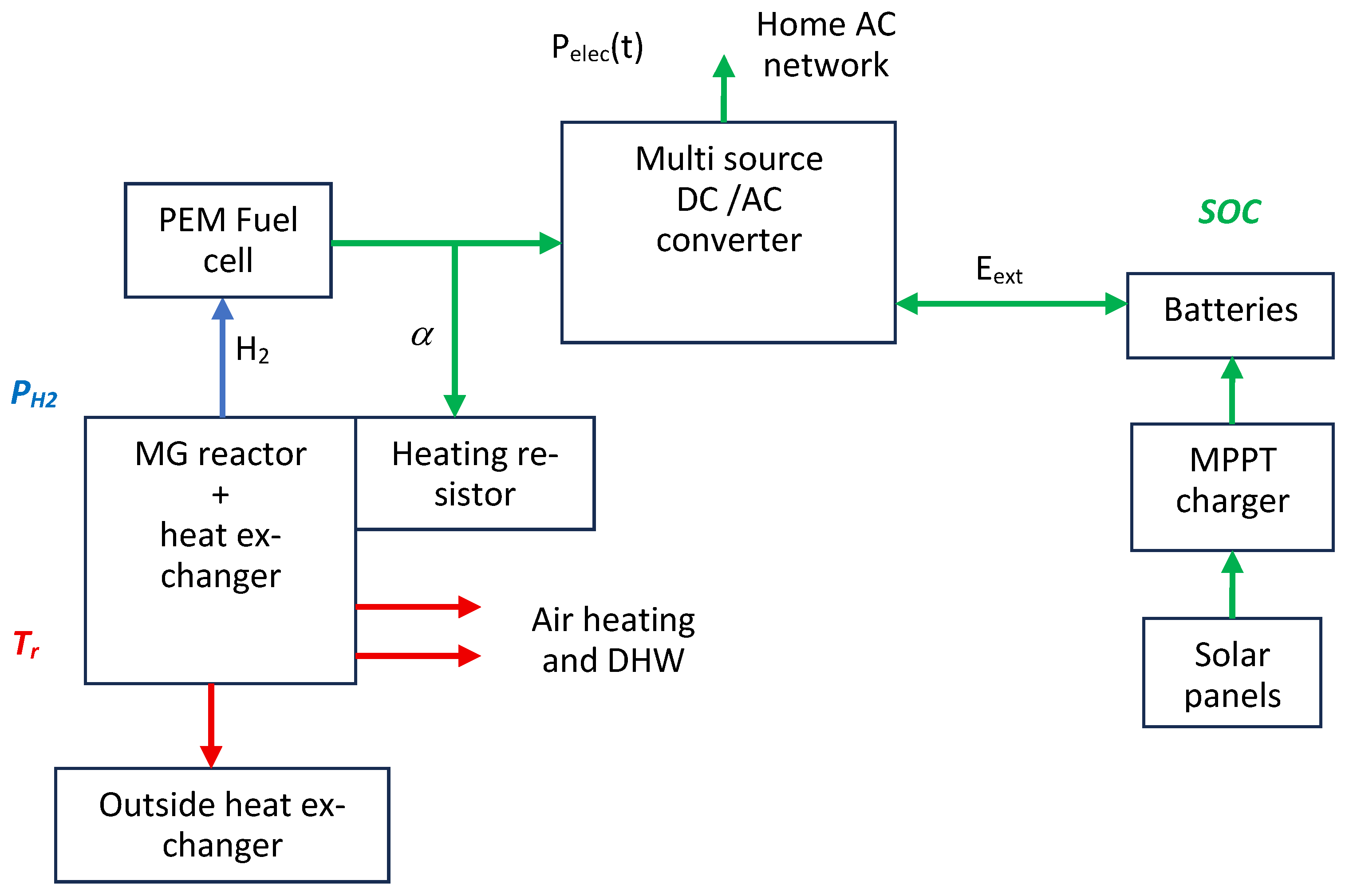

4.6. A Solution for the Implementation of Strategy 5

- -

- for SOC: SOC20% < SOC90% < SOC100%;

- -

- for PH2: Pmin < Plow < Pnom < Phigh < Pmax, for instance, Pnom = 2 bar;

- -

- for Tr: Tmin < Tnom < Tmax, for instance, Tnom = 70 °C.

- -

- if , create a proportional increase in to reach the value 1 if ;

- -

- if (not enough electricity consumed) and if (battery recharge) and , produce heat with the heating resistor to maintain if ;

- -

- if , create a proportional decrease in to reach the value 0 if ;

- -

- if (too much electricity consumed), and will come from the battery over a short period (which will not last since the reactor is sized to be able to cover the electrical power demands);

- -

- if , evacuate the excess heat with the “outside heat exchanger”.

- Hydrogen pressure control: Operation limited to 2 bar nominal pressure (Pnom = 2 bar, Pmax < 3 bar) using automatic valves and redundant pressure sensors.

- Temperature management: The reactor is equipped with dual temperature sensors and an external water-cooling circuit maintaining T < 70 °C.

- Hydrogen leak mitigation: All joints must use PTFE seals; gas lines must be fitted with check valves and external venting in compliance with ISO 16111 [36] (hydrogen storage–metal hydride safety).

- Powder handling: Mg powder is stored in inert N2 atmosphere cartridges; feeding is automated to minimize human exposure.

- Thermal runaway prevention: An electronic cut-off is activated if reactor T > Tmax.

- In case of abnormal pressure or temperature rise, Mg feed is automatically halted, and hydrogen is vented externally. Hydrogen detection sensors ensure safe operation under residential conditions.

5. Conclusions

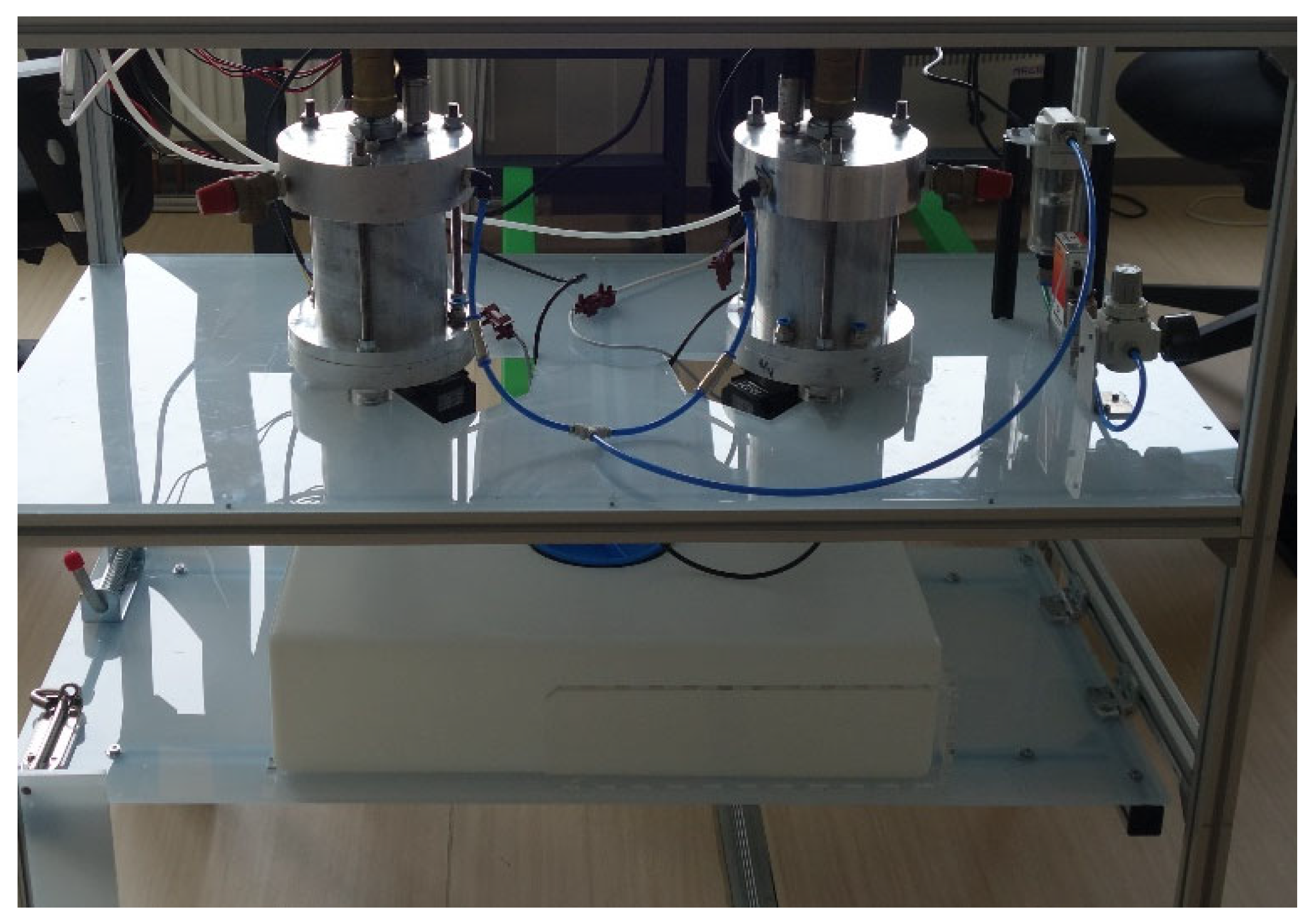

- A Mg–H2O reactor capable of on-demand H2 generation (regulated at 2 bar);

- An integrated heat recovery loop;

- A multi-strategy energy management approach combining photovoltaic generation and cogeneration optimization.

- A reduction of ≈30% in Mg consumption (from 2150 kg to 1514 kg year−1);

- A reduction of ≈50% in battery capacity compared to a PV-only system;

- A compact design, requiring <1 m3 Mg storage volume.

- -

- taking into account the dynamics of electricity and heat production by the reactor;

- -

- evaluating the benefits of using waste heat, for example, from the PEMFC stack, while also maintaining it at a temperature equal to that of the heat exchanger (the same heat exchanger could cool both the reactor and the stack);

- -

- evaluating the benefits of calculating the and profiles in strategy 5 for each month rather than for each season;

- -

- evaluating whether the implementation strategy of Section 4.5 unduly deteriorates the expected magnesium consumption levels when the consumption profiles no longer correspond entirely to the profile used with strategy 5;

- -

- evaluating the possibility of scaling up the concept;

- -

- analyzing the system lifecycle;

- -

- developing efficient solutions, Mg(OH)2, which is a limitation to the diffusion of such a cogeneration system.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khakimov, R.; Anton Moskvin, A.; Zhdaneev, O. Hydrogen as a key technology for long-term & seasonal energy storage applications. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 68, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdin, Z.; Al Khafaf, N.; McGrath, B.; Catchpole, K.; Gray, E. A review of renewable hydrogen hybrid energy systems towards a sustainable energy value chain. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2023, 7, 2042–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfi, H.; Hitchmough, D.; Armin, M.; Blanco-Davis, E. A Study on the Viability of Fuel Cells as an Alternative to Diesel Fuel Generators on Ships. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, R.; Niroula, S.; Pandey, B.; Subedi, A.; Singh Thapa, B. Techno-economic assessment of fuel cell-based power backup system as an alternative to diesel generators in Nepal: A case study for hospital applications. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 56, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, A.; Hafeznia, H.; Marc, A.; Rosen, M.A.; Pourfayaz, F. Optimization of a grid-connected hybrid solar-wind-hydrogen CHP system for residential applications by efficient metaheuristic approaches. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 123, 1263–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.L.; Lewis, A.C. Decarbonisation of heavy-duty diesel engines using hydrogen fuel: A review of the potential impact on NOx emissions. Environ. Sci. Atmos. 2022, 2, 852–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daraei, M.; Campana, P.E.; Anders, A.; Jurasz, J.; Thorin, E. Impacts of integrating pyrolysis with existing CHP plants and onsite renewable-based hydrogen supply on the system flexibility. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 243, 114407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boait, P.J.; Greenough, R. Can fuel cell micro-CHP justify the hydrogen gas grid? Operating experience from a UK domestic retrofit. Energy Build. 2019, 194, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, S.; Michaux, G.; Salagnac, P.; Bouvier, J.L. Micro-combined heat and power systems (micro-CHP) based on renewable energy sources. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 154, 262–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radenahmad, N.; Azad, A.T.; Saghir, M.; Taweekun, J.; Abu Bakar, M.S.; Reza Md, S.; Azad, A.K. A review on biomass derived syngas for SOFC based combined heat and power application. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 119, 109560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Maharjan, K.; Cho, H. A review of hydrogen utilization in power generation and transportation sectors: Achievements and future challenges. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 28629–28648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, R.; Casisi, M.; Micheli, D.; Reini, M. A Review of Small–Medium Combined Heat and Power (CHP) Technologies and Their Role within the 100% Renewable Energy Systems Scenario. Energies 2021, 14, 5338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasul, M.G.; Hazrat, M.A.; Sattar, M.A.; Jahirul, M.I.; Shearer, M.J. The future of hydrogen: Challenges on production, storage and applications. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 272, 116326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, T.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Huang, H.; Liu, B.; Li, Y.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, B.; Wu, Y. Utlra-Fast Hydrolysis Performance of MgH2 Catalyzed by Ti-Zr-Fe-Mn-Cr-V High-Entropy Alloys. J. Energy Chem. 2024, 98, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.; Urretavizcaya, G.; Bobet, J.-L.; Castro, F.J. Effective Hydrogen Production by Hydrolysis of Mg Wastes Reprocessed by Mechanical Milling with Iron and Graphite. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 946, 169352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhatib, R.; Petrone, R.; Louahlia, H. Dynamic Study of Hydrogen Optimization in the Hybrid Boiler-Fuel Cells MCHP Unit for Eco-Friendly House. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 56, 973–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarlet, L.; Kabongo, L.; Marques, D.; Bobet, J.L. Advances in Hydrolysis of Magnesium and Alloys: A Conceptual Review on Parameters Optimization for Sustainable Hydrogen Production. Metals 2025, 15, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Wu, T.; Yang, Y. Research Progress in Hydrogen Production by Hydrolysis of Magnesium-Based Materials. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 696–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayeh, T.; Awad, A.S.; Nakhl, M.; Zakhour, M.; Silvain, J.F.; Bobet, J.L. Production of hydrogen from magnesium hydrides hydrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 3109–3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, A.S.; El-Asmar, E.; Tayeh, T.; Mauvy, F.; Nakhl, M.; Zakhour, M.; Bobet, J.-L. Effect of carbons (G and CFs), TM (Ni, Fe and Al) and oxides (Nb2O5 and V2O5) on hydrogen generation from ball milled Mg-based hydrolysis reaction for fuel cell. Energy 2016, 95, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Ouyang, L.; Zeng, M.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Shao, H.; Zhu, M. Realizing facile regeneration of spent NaBH4 with Mg–Al alloy. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 10723–10728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, S.X.; Vincent, J.; Razak, N.F.; Daud, N.; Chowdhury, S.; Wongchoosuk, C.; Chia, C.H. Advancements and challenges in sodium borohydride hydrogen storage: A comprehensive review of hydrolysis, regeneration, and recycling technologies. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2025, 17, 12702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Pan, Z.H.; Zhao, C.Y. Experimental study of MgO/Mg(OH)2 thermochemical heat storage with direct heat transfer mode. Appl. Energy 2020, 275, 115356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasmar, E.; Awad, A.S.; Hachem, D.; Tayeh, T.; Nakhl, M.; Zakhour, M.; Gaudin, E.; Bobet, J.-L. Hydrogen generation from Nd-Ni-Mg system by hydrolysis reaction. J. Alloy Compd. 2018, 740, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Ouyang, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Shao, H.; Zhu, M. Enhanced hydrogen generation by hydrolysis of Mg doped with flower-like MoS2 for fuel cell applications. J. Power Sources 2017, 365, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legree, M.; Sabatier, J.; Mauvy, F.; Awad, A.S.; Faessel, M.; Bos, F.; Bobet, J.L. Autonomous Hydrogen Production for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells PEMFC. J. Energy Power Technol. 2020, 2, 004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://librairie.ademe.fr/societe-et-politiques-publiques/7130-panel-usages-electrodomestiques-annee-4.html#product-presentation (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Consommation Électrique Heure par Heure des Postes de Dépense Domestiques. Available online: https://www.data.gouv.fr/datasets/consommation-electrique-heure-par-heure-des-postes-de-depense-domestiques/ (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Thomas, T. Étude Technico-Économique de la Mise en Place d’un Système de Récupération de Chaleur sur les Eaux Grises Pour un Lotissement Résidentiel au Grand-Duché de Luxembourg. Master’s Thesis, University of Liège, Liège, Belgium, 2020. Available online: https://matheo.uliege.be/bitstream/2268.2/9640/5/THIRY_THOMAS-%C3%89tude%20technico-%C3%A9conomique%20de%20la%20mise%20en%20place%20d%E2%80%99un%20syst%C3%A8me%20de%20r%C3%A9cup%C3%A9ration%20de%20chaleur%20sur%20les%20eaux%20grises%20pour%20un%20lotissement%20r%C3%A9sidentiel%20au%20Grand-Duch%C3%A9%20de%20Luxembourg.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- De Oreo, W.B.; Mayer, P.; Dziegielewski, B.; Kiefer, J. Residential End Uses of Water, 2nd ed.; Water Research Foundation: Denver, CO, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/WRF_REU2016.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Ni, L.; Lau, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, T.; Stansbury, J.; Shi, J.; Neal, J. Feasibility study of a localized residential grey water energy-recovery system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2012, 39, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costic. Guide sur les Besoins D’eau Chaude Sanitaire en Habitat Individuel et Collectif. Available online: https://www.costic.com/ressources/documentation-et-outils/guide-sur-les-besoins-deau-chaude-sanitaire-en-habitat-individuel-et-collectif (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Kabalo, M.; Machado, R.; Pombo, J. Performance analysis of inverters used in standalone photovoltaic systems. Renew. Energy 2021, 174, 1025–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M.; Khandekar, S. Thermal performance of serpentine heat exchangers under various flow and inclination configurations. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 178, 115557. [Google Scholar]

- Tocci, L.; Pal, T.; Pesmazoglou, I.; Franchetti, B. Small Scale Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC): A Techno-Economic Review. Energies 2017, 10, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO16111:2018; Transportable Gas Storage Devices—Hydrogen Absorbed in Reversible Metal Hydride. Edition 2. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/67952.html (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Jeoung, H.J.; Lee, T.H.; Yi, K.W.; Kang, J. Review on Electrolytic Processes for Magnesium Metal Production: Industrial and Innovative Processes. Mater. Trans. 2025, 66, 823–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| End-Use | Volume (L/Day) [30] | Temperature T (°C) [31] |

|---|---|---|

| Shower | 67.4 | 40.6 |

| Sink | 58.3 | 40.6 |

| Bath | 9.8 | 40.6 |

| Season | Winter | Spring | Summer | Autumn | Total for 1 Year [kg] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily magnesium consumption [kg] with strategy 3 | 7.09 | 5.67 | 5.58 | 5.56 | 2150 |

| Daily magnesium consumption [kg] with strategy 4 | 7.07 | 4.34 | 2.46 | 3.51 | 1565 |

| Daily magnesium consumption [kg] with strategy 5 | 6.59 | 3.97 | 2.19 | 4.08 | 1514 |

| Season | Winter | Spring | Summer | Autumn |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum (25) | 1.82 | 3.81 | 1.25 | 1.23 |

| Season | Winter | Spring | Summer | Autumn |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (kWh) | 1.91 | 3.19 | 3.37 | 2.04 |

| Strategy | Mg Consump. | H2 Yield | Electricity Efficiency | Heat Efficiency | Additional Source | Battery Need | System Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lack of heat in winter: unusable strategy | ||||||

| 2 | Lack of electricity in summer: an unusable strategy | ||||||

| 3 | 2150 kg/year | 95% | 40% | 32% | No | No | + |

| 4 | 1565 kg/year | 95% | 38% | 38% | No | No | +++ |

| 5 | 1516 kg/year | 95% | 40% | 38% | PV | Yes | ++ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sabatier, J.; Chouder, R.; Bedecarrats, J.-P.; Bobet, J.-L.; Mauvy, F.; Faessel, M. Decentralized Hydrogen Production from Magnesium Hydrolysis for Off-Grid Residential Applications. Hydrogen 2025, 6, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040117

Sabatier J, Chouder R, Bedecarrats J-P, Bobet J-L, Mauvy F, Faessel M. Decentralized Hydrogen Production from Magnesium Hydrolysis for Off-Grid Residential Applications. Hydrogen. 2025; 6(4):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040117

Chicago/Turabian StyleSabatier, Jocelyn, Ryma Chouder, Jean-Pierre Bedecarrats, Jean-Louis Bobet, Fabrice Mauvy, and Matthieu Faessel. 2025. "Decentralized Hydrogen Production from Magnesium Hydrolysis for Off-Grid Residential Applications" Hydrogen 6, no. 4: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040117

APA StyleSabatier, J., Chouder, R., Bedecarrats, J.-P., Bobet, J.-L., Mauvy, F., & Faessel, M. (2025). Decentralized Hydrogen Production from Magnesium Hydrolysis for Off-Grid Residential Applications. Hydrogen, 6(4), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040117