1. Introduction

One of the most pressing socio-environmental issues of the twenty-first century is energy sustainability. In the Western Balkans—Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia—where major energy challenges impact economic growth, environmental sustainability, and energy security, this is particularly pertinent [

1]. Albania’s annual energy demand is projected to rise by 77% by 2030 [

2] with 98% of electricity generated from hydropower [

3]. This dependence exposes the country to significant risks from climate-induced fluctuations in water availability, particularly during dry seasons [

4]. These risks are further amplified by rising electricity prices, aging infrastructure, and increasing demand driven by economic growth and expanding tourism. Together, they highlight the pressing need to diversify Albania’s national energy mix [

1,

2,

4]. Additionally, the urgency of the situation is intensified by broader regional challenges, such as fragile or recovering economies, insufficient funding for environmental protection, weak legislation and enforcement, low levels of public engagement, and ongoing political instability [

5].

In response to energy challenges, Albania has made notable strides in expanding solar and wind energy capacities, with technical potential estimated at 2378 MW for photovoltaic (PV) and 7483 MW for wind [

6]. However, the intermittent nature of renewable energy sources presents challenges for grid stability, storage, and demand balancing [

7]. Within this context, hydrogen production via electrolysis offers significant advantages, including high energy density, long-term storage potential, and cross-sectoral applications [

8]. Hydrogen has emerged globally as a promising energy vector due to its versatility in storage and transport and its potential to decarbonize power, transport, and industrial sectors [

9,

10].

For Albania, the development of hydrogen technologies is not only essential to overcome the limitations of intermittent renewable energy but also presents a strategic opportunity to utilize natural gas from the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) as a transitional input for blue hydrogen production. This dual approach—linking renewable-based green hydrogen and low-carbon hydrogen from TAP—could enhance Albania’s energy resilience, reduce its dependence on hydropower, and support its alignment with EU decarbonization targets. Yet the successful deployment of hydrogen technologies does not depend on technical or economic feasibility alone. Public acceptance is increasingly recognized as a central determinant of whether hydrogen technologies can be deployed at scale [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Early foundational work by Schulte et al. [

15] emphasized that the public acceptance of hydrogen is influenced not only by technical performance but also by psychological factors such as perceived risk, familiarity, and trust in institutions, laying the groundwork for more recent multidimensional models. Theoretical frameworks such as Gordon et al.’s [

16] five-dimensional model offer a structured approach to analyze this issue. The frameworks emphasize that social acceptance is shaped by an interplay of sociopolitical acceptance, community acceptance, and market adoption—each is influenced by awareness, perceived benefits and risks, fairness, trust, and socio-demographic characteristics [

13,

17,

18,

19]. A substantial body of international research supports this conceptual framing. While public awareness of hydrogen is necessary for social acceptance, it does not guarantee it. In Japan, the UK, and the Netherlands, increased familiarity with hydrogen has not always translated into support for local projects [

13]. More than 60% of countries report low public awareness, often associated with misconceptions or safety concerns [

13,

20,

21]. Even in the EU, where a Gallup survey found 82% of citizens had recently encountered hydrogen-related information [

14], local opposition remains a barrier, as also evidenced in Australia, where only one-third of respondents supported hydrogen plants in their communities [

19].

Trust plays a pivotal role in shaping perceptions and acceptance. Confidence in regulatory bodies, scientific institutions, and private developers often determines public willingness to support new technologies, alongside perceptions of transparency, fairness, and safety [

16,

22,

23]. Socio-demographic factors such as age, education, and gender further mediate acceptance, with several studies confirming their predictive value in contexts like Malaysia and South Korea [

16,

17,

18,

24,

25]. As Gordon et al. [

16] argue, social acceptance must be understood across attitudinal, sociopolitical, community, market, and behavioral dimensions. These include not just cognitive assessments but also emotional and normative factors such as environmental concern, risk perception, and procedural justice [

26,

27,

28]. In Germany and Australia, even generally favorable national attitudes toward hydrogen weaken when specific local siting is proposed, illustrating the “Not in My Backyard” (NIMBY) effect and the need for inclusive, participatory engagement [

11,

19,

28,

29].

Despite this expanding body of evidence, a clear research gap remains: little is known about public perceptions of hydrogen technologies in Southeast Europe. Existing studies tend to focus on broader energy attitudes or policy scenarios without integrating public opinion data, leaving the social acceptance dimension underexplored. This lack of context-specific knowledge risks undermining investment, infrastructure planning, and citizen buy-in for hydrogen initiatives, particularly as the EU prioritizes the creation of hydrogen corridors across the Western Balkans, where public support will be a decisive success factor.

This study fills that gap by providing the first empirical assessment of hydrogen acceptance in Albania. Based on a structured online survey, it investigates public awareness, perceived risks and benefits, trust in institutions, and willingness to adopt hydrogen-based solutions. The results provide context-specific evidence to inform both policy and practice, offering conceptual insights and actionable guidance for advancing a socially inclusive, fair, and resilient hydrogen transition in Albania, contributing directly to the EU’s regional hydrogen integration goals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study employed a quantitative, cross-sectional research design using a structured online survey to assess public perceptions and acceptance of hydrogen technologies in Albania. The research instrument was developed in accordance with international guidelines and theoretical frameworks from the Clean Hydrogen Partnership [

14], as well as peer-reviewed literature on the social acceptance of energy technologies [

13,

16,

23]. Given the absence of prior empirical data on hydrogen perception in Albania, a descriptive and exploratory approach was deemed appropriate to capture baseline attitudes and inform future research. To ensure broader representativeness beyond the digitally literate population, the survey was disseminated through a combination of multiple distribution channels, including academic mailing lists, institutional websites, social media platforms, and community organizations. A mixed sampling strategy was employed, integrating purposive sampling (targeting individuals likely to have relevant views or knowledge), snowball sampling (encouraging participants to forward the survey within their networks), and random sampling elements where possible to mitigate bias and increase diversity within the respondent pool. Participation in the study was entirely voluntary, and informed consent was obtained from all respondents prior to participation. The survey guaranteed full anonymity and did not collect any personally identifiable information. All procedures adhered to internationally recognized ethical research standards and were designed to ensure data confidentiality, transparency, and the protection of participants’ rights.

2.2. Survey Instrument

The online questionnaire, administered via Google Forms, was developed to comprehensively assess public perceptions and acceptance of hydrogen technologies in Albania. It consisted of closed-ended multiple-choice questions and five-point Likert-scale items ranging from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree”. The instrument was organized around five thematic domains: (1) awareness and knowledge of hydrogen technologies; (2) perceived risks and benefits, including environmental, safety, and economic considerations; (3) trust in institutions and technology developers, such as government agencies, scientists, and private companies; (4) willingness to adopt hydrogen-based applications and support local deployment; and (5) pro-environmental motivation, capturing underlying environmental values and attitudes.

To allow for further analysis, the questionnaire also included a set of socio-demographic items, collecting data on age, gender, education level, and employment status. These variables enabled the exploration of associations between individual characteristics and attitudes toward hydrogen technologies.

The survey instrument was adapted from internationally validated questionnaires used in previous studies, including those developed under the Clean Hydrogen Partnership and peer-reviewed research on social acceptance of energy innovations. Items were refined to ensure cultural and contextual relevance to the Albanian setting, while maintaining alignment with existing theoretical frameworks. To ensure clarity and validity, the questionnaire underwent cognitive pre-testing with 15 individuals of varying backgrounds. Feedback from this process led to minor adjustments in item wording to enhance comprehension and eliminate ambiguity.

Reliability analysis showed strong internal consistency across the attitudinal scales, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84, indicating a high degree of reliability in measuring public attitudes toward hydrogen technologies.

2.3. Sampling and Data Collection

Data for this study were collected over a three-month period, from May to July 2025, using a combination of online and offline distribution channels. These included social media platforms, university mailing lists, professional and academic forums, as well as community outreach initiatives. A multi-pronged sampling strategy was employed to ensure diversity and inclusion. Specifically, the approach integrated purposive, snowball, and random sampling techniques. The initial phase involved purposive sampling, targeting individuals presumed to have some prior exposure to hydrogen-related topics, such as university students, engineers, researchers, and energy professionals. This was followed by snowball sampling, whereby initial participants were encouraged to share the survey link within their personal and professional networks to expand reach organically. To further enhance demographic representation—particularly among older or less digitally connected populations—random sampling was also conducted through community centers, senior networks, and local associations.

A total of 502 responses were received, of which 440 were deemed valid and included in the final analysis. Mainly from the online submissions, 62 responses were excluded because key demographic or perception questions were left unanswered, or because they contained inconsistent or clearly invalid information (e.g., contradictory answers to related items). This final sample size exceeds the commonly recommended threshold of 10 participants per variable in exploratory survey research and is considered sufficient for identifying preliminary trends and associations. Although the use of non-probability sampling limits the generalizability of the findings to the broader Albanian population, the dataset nonetheless represents a diverse cross-section of respondents in terms of age, educational background, and occupational status. As such, the results provide valuable baseline insights into public perceptions of hydrogen technologies in Albania and offer a strong foundation for future, more representative investigations.

2.4. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics—including frequencies, percentages, and means—were calculated using Microsoft Excel [

30] to summarize key variables such as awareness, trust, perceived risks and benefits, and socio-demographic characteristics. In addition to descriptive summaries, chi-square tests of independence were conducted to examine associations between categorical variables, such as gender and awareness of hydrogen technologies, or age group and perceived safety.

All chi-square tests were performed in Excel using manually constructed contingency tables and the built-in CHISQ.TEST function. This approach was appropriate given the exploratory nature of the study and the categorical structure of the variables under investigation.

Although logistic regression and other inferential techniques (e.g., Odds Ratios, Confidence Intervals, Nagelkerke R2) are commonly used in similar studies to explore predictive relationships, these analyses were not conducted for two key reasons. First, the study’s design was primarily descriptive and exploratory, aiming to establish baseline insights rather than causal or predictive inferences. Second, the research team opted to avoid more complex multivariate analysis due to practical constraints, including limitations in statistical software access and the need to ensure transparency and replicability using accessible tools such as Excel.

Despite these limitations, the use of chi-square tests provided meaningful insights into significant associations between public perceptions and socio-demographic factors, laying the groundwork for more advanced, representative, and inferential analyses in future research.

2.5. Study Limitations

This study has several limitations that warrant consideration.

First, the use of non-probability sampling methods, particularly snowball and purposive sampling, introduces potential selection bias. Despite outreach through community networks and offline channels, the sample is skewed toward younger, urban, and highly educated individuals, limiting the representativeness of the findings, especially for older adults, rural populations, or those with lower educational attainment.

Second, all measures were self-reported, including perceived awareness and knowledge of hydrogen technologies, which may be subject to overconfidence or social desirability bias, particularly in explaining gender-based differences.

Third, the cross-sectional design prevents the analysis of how public perceptions evolve over time or in response to technological developments and policy changes.

Fourth, the study’s analytical scope is limited to descriptive and bivariate analyses using chi-square tests, without multivariate or predictive modeling (e.g., logistic regression or structural equation modeling), thereby reducing inferential power.

Finally, the focus on social perceptions excludes technical, economic, or policy-oriented dimensions such as cost–benefit analysis, infrastructure readiness, or energy justice considerations, which could further contextualize public attitudes. These limitations underscore the exploratory nature of the study and highlight the need for future research using representative samples, longitudinal designs, and interdisciplinary approaches to more fully understand the dynamics of hydrogen acceptance in Albania.

4. Discussion

This study offers one of the first empirical investigations into public acceptance of hydrogen technologies in Albania, a topic that remains underexplored in both national and regional contexts. The findings reveal that public perceptions are shaped by a complex interplay of awareness, perceived environmental and strategic benefits, safety concerns, and trust in institutions. These dynamics reflect patterns observed globally, where initial support for hydrogen’s climate benefits often coexists with limited technical familiarity and uncertainty about local deployment risks [

13,

14,

22,

31].

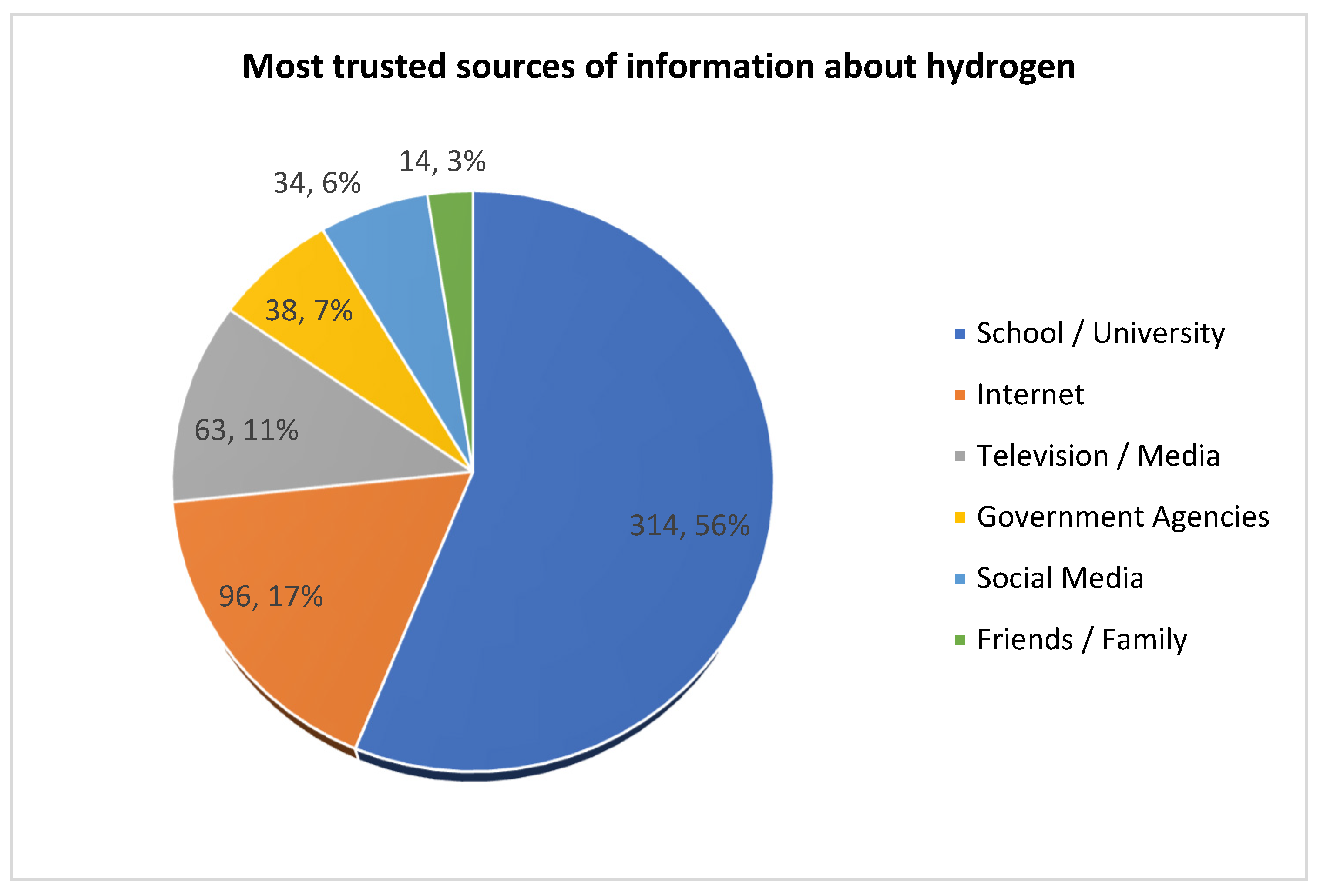

In our sample, 83.5% of respondents had heard of hydrogen as an energy source, yet only 23.8% reported being “quite familiar” with its technologies. This mirrors international patterns: despite moderate-to-high exposure to hydrogen information in the EU [

14], countries like Australia, England, Finland, Germany, and Japan still report significant knowledge gaps and public confusion, often associating hydrogen with past accidents or technical ambiguity [

13,

17]. Odoi-Yorke et al. [

31] similarly noted that even as hydrogen acceptance research expands, public familiarity remains superficial. Vallejos-Romero et al. [

32] likewise emphasized that weak public familiarity constrains meaningful social evaluation and adoption. In contrast, Germany, Norway, Malaysia, and Spain exhibit relatively higher awareness levels, often supported by national education and policy initiatives [

18,

26]. For example, Hildebrand et al. [

33] explored how risk perceptions linked to hydrogen infrastructure vary based on the type of risk and the social context, stressing that proactive communication strategies can significantly improve public acceptance.

However, as several studies emphasize, awareness alone does not guarantee support. For example, Lopez Lozano et al. [

19] found that while many Australians were aware of hydrogen, only one-third supported deployment near their homes, a striking manifestation of the “Not in My Backyard” (NIMBY) phenomenon. This has led scholars to call for theoretical shifts. The transition from early NIMBY-focused narratives toward frameworks of procedural and distributive justice reflects what Batel [

34] describes as the evolution from normative and criticism waves to critical approaches in the study of renewable energy acceptance. These critical approaches emphasize systemic inequalities, participatory inclusion, and culturally embedded perceptions, highlighting that public resistance is often rooted in structural injustices rather than irrational fear. Applying such frameworks can help reframe hydrogen acceptance not merely as an issue of awareness, but as a justice-oriented energy transition challenge, especially relevant in Albania’s context of institutional mistrust and demographic disparities. Similarly, Yap and McLellan [

24] showed that even as hydrogen familiarity increased in Japan between 2008 and 2022, public support remained steady and ambiguous. Cultural predispositions can further shape these dynamics. In the Netherlands, Achterberg et al. [

20] observed generally high support for hydrogen despite low levels of knowledge, while in the UK, awareness and acceptability were closely tied to gender, age, education, and environmental values [

21]. These patterns confirm that while raising awareness is essential, it is not sufficient—people may still harbor distrust, misinformation, or contextual fears [

17,

22,

23].

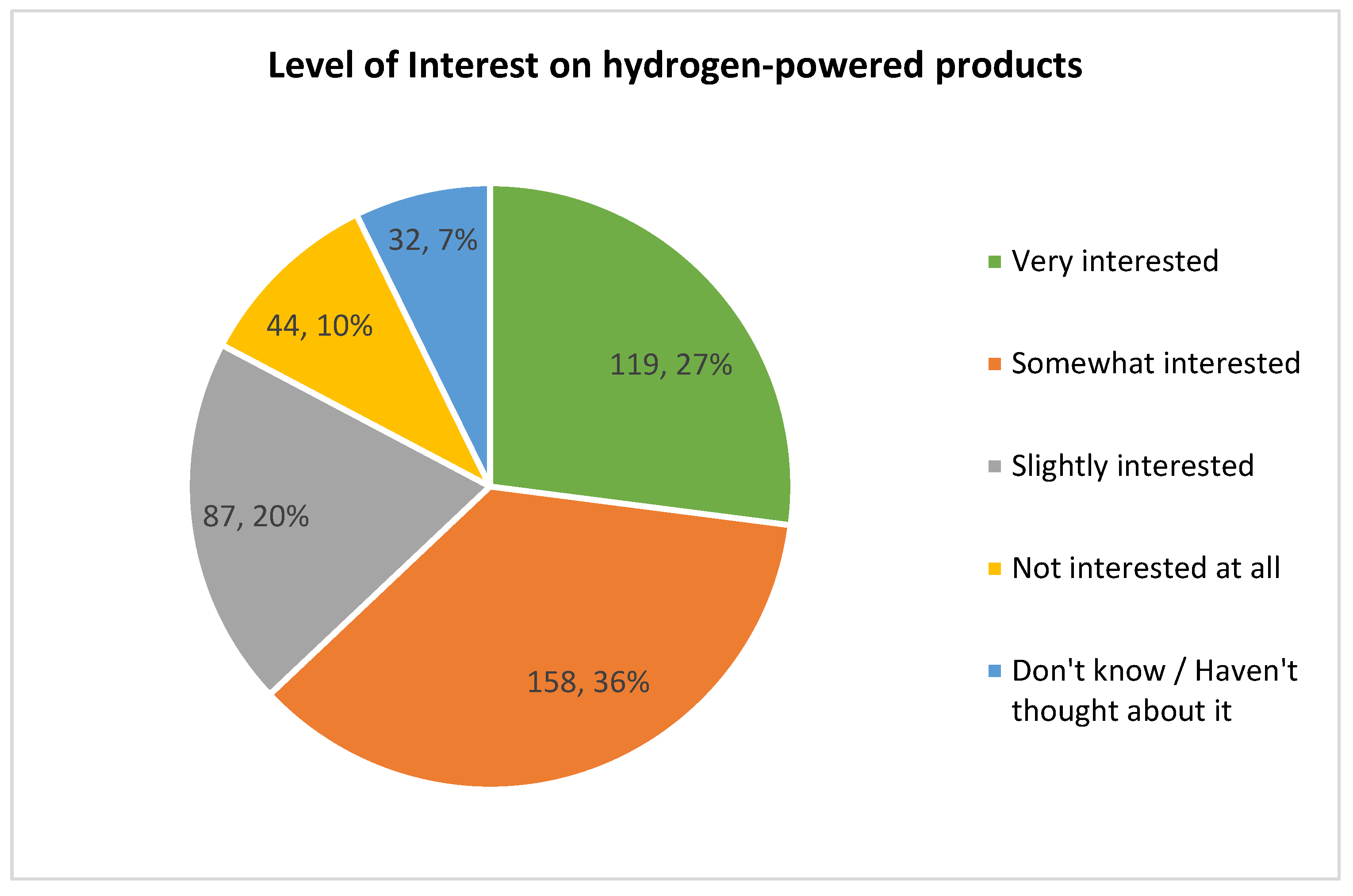

Our study reinforces these insights. While Albanian respondents expressed strong interest in hydrogen’s environmental benefits—67.4% agreeing it could reduce energy dependence, and 74.6% seeing it as a tool for GHG reduction—only 9.3% felt “very informed”. Gender-based differences were pronounced: male participants were significantly more likely to report awareness (χ

2 = 11.33,

p = 0.010), knowledge (χ

2 = 20.44,

p < 0.001), and support for local deployment (χ

2 = 9.74,

p = 0.0077) than female respondents. These differences may reflect unequal access to technical discourse, risk perception tendencies, or confidence in emerging technologies, as also noted by Gordon et al. [

16]. Other demographic variables such as age, education, and employment were not significant, suggesting a still-fluid attitudinal landscape in Albania where hydrogen remains a relatively new concept. These findings can be interpreted through the lens of energy justice, which emphasizes fair distribution of energy benefits, inclusive decision-making, and recognition of vulnerable groups [

35]. The gender gap in awareness and support may reflect deeper recognition and procedural injustices, for example, women’s caregiving roles or limited inclusion in technical debates. Concerns about safety and infrastructure also raise distributional justice issues, particularly for rural or low-income communities that may lack access to hydrogen systems. As Sovacool [

35] and colleagues argue, energy systems often reproduce social and spatial inequalities. Addressing these dimensions is essential to ensure that Albania’s hydrogen transition is both equitable and inclusive.

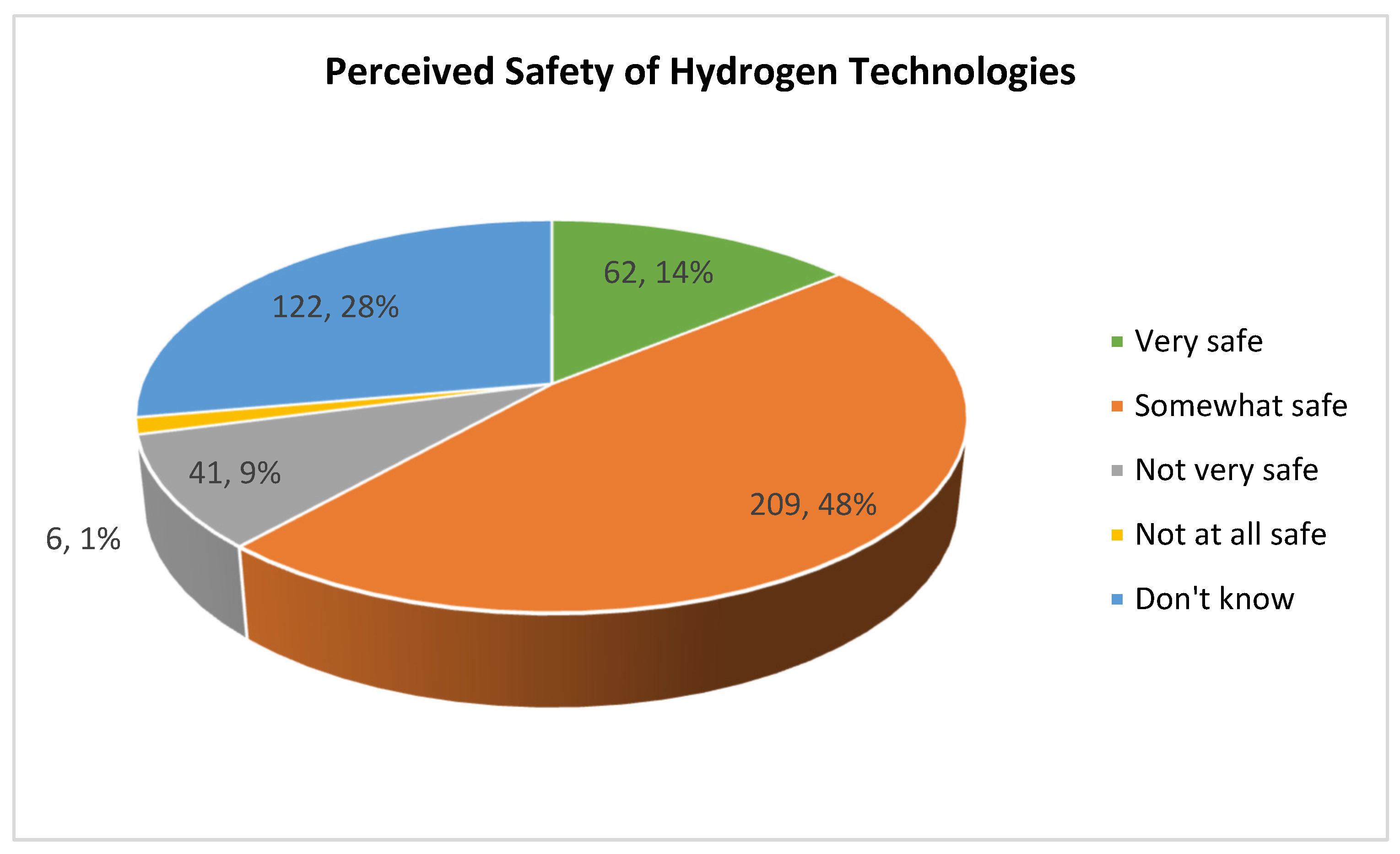

Safety emerged as a consistent concern. While the majority of respondents agreed that hydrogen is clean and potentially safe, 34.5% believed it might be dangerous near homes or schools, and 50% were unsure. Globally, similar uncertainty persists. Dumbrell et al. [

36] demonstrated that safety concerns can even outweigh climate motivations in shaping public attitudes, while Lee et al. [

37] linked poor policy transparency to diminished trust in hydrogen risk management in South Korea. Ingaldi and Klimecka-Tatar [

38] and Gordon et al. [

16] also highlight that unless local communities are confident in the safety and social value of hydrogen applications, resistance is likely, regardless of national environmental goals.

Trust in institutions is pivotal. In this study, only 43% of respondents expressed trust in the Albanian government to regulate hydrogen technologies, mirroring concerns seen in the Netherlands [

20], Germany [

28], and Australia [

29]. Vallejos-Romero et al. [

32] and Parente et al. [

39] critique many national hydrogen strategies as overly top–down, risking alienation of local actors. Transparent communication, participatory governance, and visible community co-benefits are therefore essential. A recent study in South Korea by Cho and Lee [

40] also found that public acceptance of green hydrogen is significantly influenced by perceptions of climate urgency and trust in government policies, emphasizing the importance of aligning communication with climate values and building institutional credibility. Gordon et al. [

41] argues that coupling hydrogen infrastructure with procedural justice and economic inclusion—such as through “hydrogen homes” or community-led pilot projects—can foster deeper legitimacy. To help alleviate public fears, technical reliability must be clearly communicated through demonstrable safety mechanisms. Notably, recent advances in real-time fuel cell health monitoring—such as those presented in Meng et al. [

42]—offer promising tools to detect malfunctions and reduce operational risks. Highlighting such innovations can reinforce public confidence in hydrogen safety, especially when integrated into community-facing education and policy messaging.

This aligns with broader theoretical work. Schulte et al. [

15] and Gordon et al. [

16] emphasize that social acceptance is shaped by attitudinal, sociopolitical, market, community, and behavioral dimensions, not just technical ones. Sala et al. [

26] and Son et al. [

25] confirm that trust, safety, affective responses, and participation are decisive for local acceptance. Hienuki et al. [

27] and Häußermann et al. [

28] highlight the value of direct, experiential exposure—beyond facts and figures—in building acceptance. Beasy et al. [

29] show how industry–community mismatches in values (e.g., safety vs. climate responsibility) can block consensus. Schönauer & Glanz [

11] and Lopez Lozano et al. [

19] further underscore the contrast between general support and local resistance, reinforcing the need for targeted, location-sensitive outreach.

In light of these insights, our findings underscore the importance of adopting a multidimensional strategy for Albania, aligned with the framework proposed by Gordon et al. [

16]. Specifically, there is a pressing need to launch inclusive, science-based education campaigns that address the gender gap in awareness; prioritize transparent and proactive risk communication, drawing from models such as those implemented in South Korea [

37]; emphasize renewable-based hydrogen production to reflect environmental values and reduce reliance on fossil-based transitional fuels; and embed hydrogen initiatives within local community benefit frameworks that promote procedural justice and co-ownership. Future research should aim to track changes in public perception longitudinally as pilot projects evolve [

22], explore cross-national patterns within the Western Balkans to identify sociopolitical or cultural differences [

13], and investigate behavioral dynamics linking expressed attitudes to actual adoption [

23]. Additionally, in-depth gender-sensitive studies are needed to uncover structural barriers to informed support, while participatory planning experiments can help determine how community-level gains influence acceptance [

16,

27].

Overall, this study highlights the complex and layered nature of hydrogen acceptance in Albania, where public optimism regarding environmental benefits coexists with limited knowledge, safety concerns, and cautious trust in institutions. The observed gender-based differences further emphasize the importance of equitable communication and inclusive engagement. By addressing knowledge gaps, fostering transparent governance, and embedding tangible local benefits, Albania can lay a socially robust and nationally grounded foundation for a successful hydrogen transition.

5. Conclusions

This study represents the first systematic investigation of public perceptions and acceptance of hydrogen technologies in Albania, filling a significant knowledge gap in the Western Balkans. The results indicate that while general awareness of hydrogen as an energy source is relatively high, technical familiarity remains limited. Respondents expressed broadly positive attitudes, recognizing hydrogen’s potential to reduce energy dependence and greenhouse gas emissions. However, concerns about safety—particularly regarding deployment near homes and schools—along with limited access to information, insufficient infrastructure, and moderate institutional trust, emerged as key barriers to acceptance.

To address these challenges, policymakers and energy stakeholders should implement inclusive and science-based public awareness campaigns that target both urban and rural populations, with a particular focus on reducing gender disparities in knowledge. Transparent risk communication strategies are essential to clarify safety protocols and build confidence in hydrogen technologies. Educational interventions, including curriculum integration and community outreach, can help improve understanding and reduce uncertainty. Additionally, participatory planning frameworks—such as co-designed pilot projects or local benefit-sharing schemes—can foster procedural justice and enhance legitimacy. As a first step, it is crucial that the Albanian government formally integrate hydrogen into the national energy framework and strategic planning documents, providing a clear institutional mandate and investment roadmap for future development.

Future research should adopt more representative sampling methods and explore longitudinal changes in perception as Albania progresses with pilot projects or national hydrogen roadmaps. Comparative studies across the Western Balkans could illuminate regional variations, while behavioral studies are needed to understand how stated preferences align with actual adoption. Deeper gender-sensitive and energy justice analyses would also clarify structural barriers to equitable engagement.

Overall, the findings underscore the importance of socially inclusive, context-sensitive, and forward-looking strategies to support Albania’s transition toward a diversified, low-carbon energy system, aligned with European hydrogen ambitions but grounded in local realities.