Vis–NIR Spectroscopy Characteristics of Wetland Soils with Different Water Contents and Machine Learning Models for Carbon and Nitrogen Content

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Soil Sample Collection

2.3. Chemical Determination of Soil Carbon and Nitrogen Content

2.4. Spectral Data Measurement of Soil Samples with Different Moisture Contents

2.5. Soil Spectral Data Preprocessing

2.6. Selection of Characteristic Bands

2.7. Construction and Accuracy Verification of Machine Learning Models

2.8. Model Interpretation Using SHAP Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Soil Spectral Curves Under Different Moisture Contents

3.2. Continuous Projection Algorithm for Feature Bands

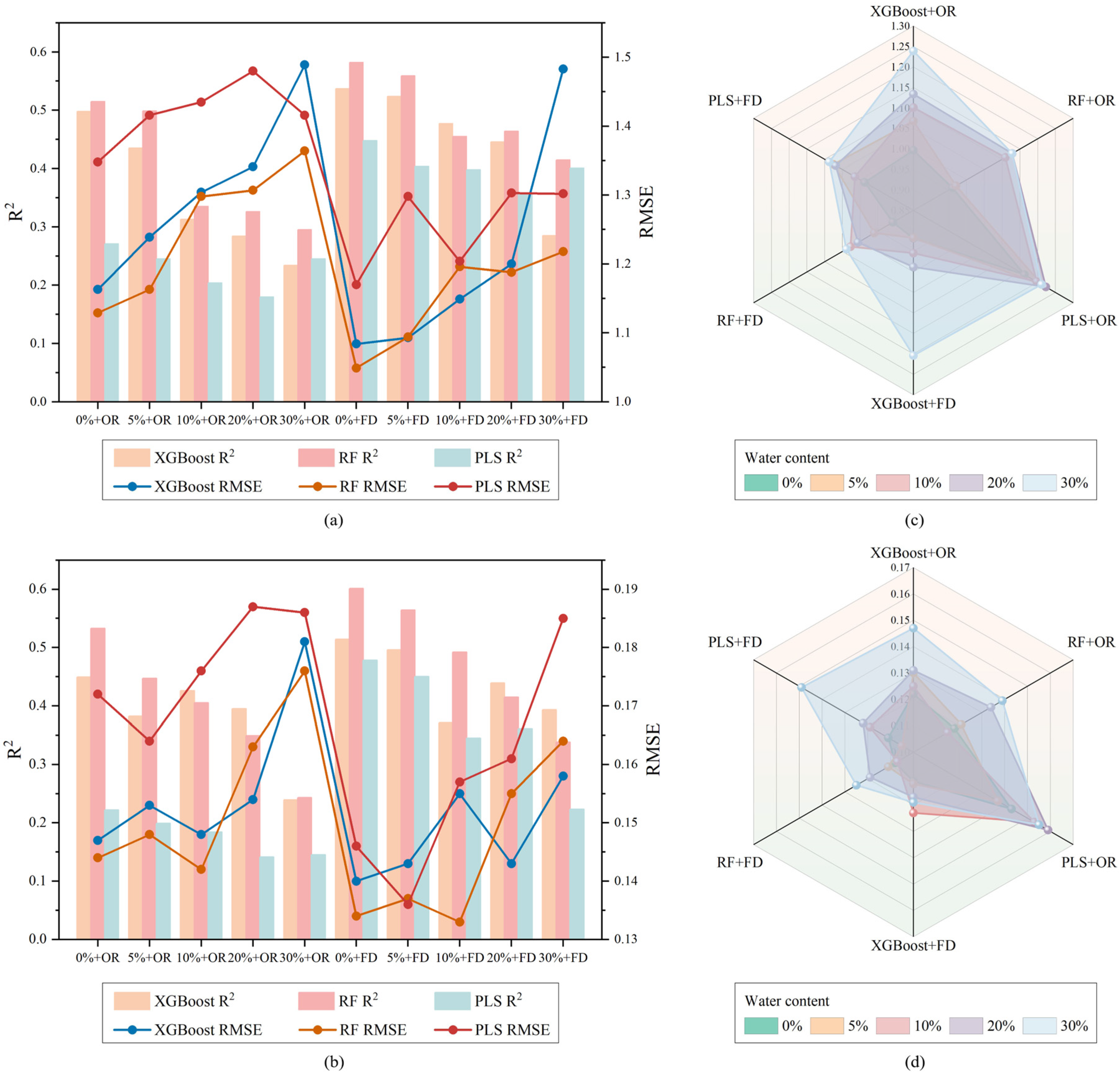

3.3. Accuracy Evaluation of Soil Element Content Model Validation Based on Full-Band Analysis of Different Moisture Contents

3.4. Accuracy Evaluation of Soil Element Content Model Validation Based on Different Moisture Content Characteristic Bands

3.5. Interpretation of Prediction Mechanisms via SHAP Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of Soil Moisture on the Accuracy of Soil Nutrient Retrieval

4.2. Differences in Element Content Inverted from Vis–NIR Spectroscopy Data

4.3. Differences in Inversion of Different Vis–NIR Spectroscopy Data of Wetland Soil

4.4. Interpretation of Prediction Mechanisms Through SHAP Analysis

4.5. Impact of Machine Models on the Accuracy of Wetland Soil Carbon and Nitrogen Inversion

- Soil Moisture Content: This is the most significant factor. Studies achieving near-perfect prediction were almost exclusively conducted on oven-dried or air-dried soils. By eliminating moisture’s masking effect, these models capture the purest spectral signal of SOC and TN. In contrast, our study intentionally introduced moisture gradients (0–30%) to simulate a more realistic field scenario, where water absorption features overwhelm the weaker spectral features of carbon and nitrogen, inevitably leading to a reduction in predictive accuracy.

- Sample Size and Diversity: The representativeness of the calibration dataset greatly influences model performance. Studies with a large number of samples (n) covering a wide range of soil types, textures, and land uses tend to build more robust but potentially less precise models (with lower maximum R2), as they must account for greater inherent variability. Studies on smaller, more homogeneous datasets can achieve very high accuracy for that specific context but may lack generalizability.

- Model and Preprocessing Choices: The choice of algorithm and spectral preprocessing significantly impacts results. Nonlinear models like RF and XGBoost, as demonstrated in our work, are better suited to handle the complex, non-linear interactions introduced by moisture compared to linear models like PLSR.

5. Conclusions

- The soil spectral reflectance values gradually increased as the soil moisture content decreased, with the 0% moisture content prediction model consistently exhibiting better accuracy than other moisture levels.

- By comparing the validation accuracy of models based on raw and FD spectra, it was found that the estimation models for SOC and TN content built on FD spectra had higher accuracy.

- The RF model based on SPA-selected characteristic bands had a validation range of 0.30–0.69, demonstrating higher inversion accuracy and greater stability.

- The SHAP analysis confirmed 1865 nm and 1419 nm as the most contributory bands for SOC and TN prediction respectively, validating the RF model’s spectral interpretation capability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yuan, J.; Liang, Y.; Zhuo, M.; Sadiq, M.; Liu, L.; Wu, J.; Xu, G.; Liu, S.; Li, G.; Yan, L. Soil nitrogen and carbon storages and carbon pool management index under sustainable conservation tillage strategy. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 10, 1082624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billings, S.A.; Lajtha, K.; Malhotra, A.; Berhe, A.A.; de Graaff, M.A.; Earl, S.; Fraterrigo, J.; Georgiou, K.; Grandy, S.; Hobbie, S.E.; et al. Soil organic carbon is not just for soil scientists: Measurement recommendations for diverse practitioners. Ecol. Appl. 2021, 31, e02290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telo da Gama, J. The role of soils in sustainability, climate change, and ecosystem services: Challenges and opportunities. Ecologies 2023, 4, 552–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, P.B.; Tjoelker, M.G.; Machado, J.-L.; Oleksyn, J. Univ ersal scaling of respiratory metabolism, size and nitrogen in plants. Nature 2006, 439, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spohn, M.; Stendahl, J. Carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus stoichiometry of organic matter in Swedish forest soils and its relationship with climate, tree species, and soil texture. Biogeosciences 2022, 19, 2171–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweetman, A.J.; Valle, M.D.; Prevedouros, K.; Jones, K.C.J. The role of soil organic carbon in the global cycling of persistent organic pollutants (POPs): Interpreting and modelling field data. Chemosphere 2005, 60, 959–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Yuan, Y.; Zhou, P.; Wang, L.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Q. Spatial distribution of soil organic carbon and total nitrogen in a micro-catchment of northeast China and their influencing factors. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Meng, X.; Ustin, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H.; Tang, H. Vis-SWIR spectral prediction model for soil organic matter with different grouping strategies. Catena 2020, 195, 104703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Chen, S.; Xu, Z.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Dai, R. Exploring appropriate preprocessing techniques for Hyperspectral soil organic matter content estimation in black soil area. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katuwal, S.; Knadel, M.; Moldrup, P.; Norgaard, T.; Greve, M.H.; de Jonge, L.W. Visible–near–infrared spectroscopy can predict mass transport of dissolved chemicals through intact soil. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, G.; Eshel, G.; Ben Dor, E. Reflectance spectroscopy as a tool for monitoring contaminated soils. In Soil Contamination; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011; p. 6790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasava, H.B.; Gupta, A.; Arora, R.; Das, B.S. Assessment of soil texture from spectral reflectance data of bulk soil samples and their dry-sieved aggregate size fractions. Geoderma 2019, 337, 914–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Bu, H.; Dong, W.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Xia, Y. Construction and evaluation of prediction model of main soil nutrients based on spectral information. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odebiri, O.; Mutanga, O.; Odind, J.; Naicker, R.; Masemola, C.; Sibanda, M. Deep learning approaches in remote sensing of soil organic carbon: A review of utility, challenges, and prospects. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misbah, K.; Laamrani, A.; Khechba, K.; Dhiba, D.; Chehbouni, A. Multi-sensors remote sensing applications for assessing, monitoring, and mapping NPK content in soil and crops in African agricultural land. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, J.; Oommen, T.; Jayakumar, P.; Alger, R. Utilizing Hyperspectral remote sensing for soil gradation. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Tong, R.; Li, Q. Hyperspectral imaging analysis for the classification of soil types and the determination of soil total nitrogen. Sensors 2017, 17, 2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Li, X.; Ren, Y.; Qian, S.; Shao, Y. Research on regional soil moisture dynamics based on Hyperspectral remote sensing technology. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2023, 18, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zea, M.; Souza, A.; Yang, Y.; Lee, L.; Nemali, K.; Hoagland, L. Leveraging high-throughput Hyperspectral imaging technology to detect cadmium stress in two leafy green crops and accelerate soil remediation efforts. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 292, 118405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, M.; Vohland, M.; Greenberg, I.; Ludwig, B.; Ortner, M.; Thiele-Bruhn, S.; Hutengs, C. Soil moisture effects on predictive VNIR and MIR modeling of soil organic carbon and clay content. Geoderma 2022, 427, 116103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesaignoux, A.; Fabre, S.; Briottet, X. Influence of soil moisture content on spectral reflectance of bare soils in the 0.4–14 μm domain. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2013, 34, 2268–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eredics, A.; Németh, Z.I.; Rákosa, R.; Rasztovits, E.; Móricz, N.; Vig, V. The effect of soil moisture on the reflectance spectra correlations in beech and sessile oak foliage. Acta Silv. Lignaria Hung. 2015, 11, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocita, M.; Stevens, A.; Noon, C.; van Wesemael, B. Prediction of soil organic carbon for different levels of soil moisture using Vis-NIR spectroscopy. Geoderma 2013, 199, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijewardane, N.K.; Ge, Y.; Morgan, C.L.S. Moisture insensitive prediction of soil properties from VNIR reflectance spectra based on external parameter orthogonalization. Geoderma 2016, 267, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minasny, B.; Hartemink, A.E. Predicting soil properties in the tropics. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2011, 106, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Baret, F.; Gu, X.; Tong, Q.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, B. Relating soil surface moisture to reflectance. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 81, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, K.; Xia, S.; Shen, Q.; Yang, B.; Song, Q.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, Y. Moisture spectral characteristics and Hyperspectral inversion of fly ash-filled reconstructed soil. Spectrochim. Acta A 2021, 253, 119590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, C.L.S.; Waiser, T.H.; Brown, D.J.; Hallmark, C.T. Simulated in situ characterization of soil organic and inorganic carbon with visible near-infrared diffuse reflectance spectroscopy. Geoderma 2009, 151, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudier, P.; Hedley, C.B.; Lobsey, C.R.; Viscarra Rossel, R.A.; Leroux, C. Evaluation of two methods to eliminate the effect of water from soil vis-NIR spectra for predictions of organic carbon. Geoderma 2017, 296, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouazen, A.M.; Kuang, B.; De Baerdemaeker, J.; Ramon, H. Comparison among principal component, partial least squares and back propagation neural network analyses for accuracy of measurement of selected soil properties with visible and near infrared spectroscopy. Geoderma 2010, 158, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Hou, J.; Zhao, J.; Clarke, N.; Kempenaar, C.; Chen, X. Predicting soil organic matter, available nitrogen, available phosphorus and available potassium in a black soil using a nearby Hyperspectral sensor system. Sensors 2024, 24, 2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Shi, T.; Fei, T.; Wang, J.; Liu, G.; Chen, Y. Prediction of total nitrogen in cropland soil at different levels of soil moisture with Vis/NIR spectroscopy. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B—Soil Plant Sci. 2014, 64, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, L.; Qu, K.; Cui, L.; Zhai, X.; Zhao, X.; Lei, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, R.; Li, W. Inversion of soil carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus in the Yellow River Wetland of Shaanxi Province using field in situ hyperspectroscopy. Front. Soil Sci. 2024, 4, 1364426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Zuo, X.; Dou, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhai, X.; Lei, Y.; Li, J.; Pan, X.; Li, W. Plant identification of Beijing Hanshiqiao wetland based on Hyperspectral data. Spectrosc. Lett. 2021, 54, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.C.U.; Saldanha, T.C.B.; Galvão, R.K.H.; Yoneyama, T.; Chame, H.C.; Visani, V. The successive projections algorithm for variable selection in spectroscopic multicomponent analysis. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2001, 57, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Dou, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zuo, X.; Lei, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhai, X.; Pan, X.; Li, W. Hyperspectral inversion of phragmites communis carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus stoichiometry using three models. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaver, J.; Humphreys, E.R.; King, D. Random forest development and modeling of gross primary productivity in the hudson bay lowlands. Can. J. Remote Sens. 2024, 50, 2355937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coblinski, J.A.; Giasson, É.; Demattê, J.A.; Dotto, A.C.; Costa, J.J.F.; Vašát, R. Prediction of soil texture classes through different wavelength regions of reflectance spectroscopy at various soil depths. Catena 2020, 189, 104485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, Z.; Yang, C.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Yan, X.; Qiao, X.; Feng, M.; Xiao, L.; Shafiq, F.; et al. Estimation of generalized soil structure index based on differential spectra of different orders by multivariate assessment. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2024, 12, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divyesh, M.; Ajay, K.; Onkar, D. Development of spectral indexes in Hyperspectral imagery for land cover assessment. IETE Tech. Rev. 2019, 36, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciampalini, A.; André, F.; Garfagnoli, F.; Grandjean, G.; Lambot, S.; Chiarantini, L.; Moretti, S. Improved estimation of soil clay content by the fusion of remote Hyperspectral and proximal geophysical sensing. J. Appl. Geophys. 2015, 116, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demattê, J.A.M.; Sousa, A.A.; Alves, M.C.; Nanni, M.R.; Fiorio, P.R.; Campos, R.C. Determining soil water status and other soil characteristics by spectral proximal sensing. Geoderma 2006, 135, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, E.; Decamps, H. Modeling soil moisture–reflectance. Remote Sens. Environ. 2001, 76, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, H.; Anderson, K.; Kuhn, N. Evaluating the influence of surface soil moisture and soil surface roughness on optical directional reflectance factors. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2014, 65, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danesh, M.; Bahrami, H.A. Modeling of soil sand particles using spectroscopy technology. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2022, 53, 2216–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, M.S.; Stutzer, D.; Turpie, K.; Stevenson, J.C. The effects of tidal inundation on the reflectance characteristics of coastal marsh vegetation. J. Coast. Res. 2009, 256, 1177–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, L.; Dou, Z.; Cui, L.; Tang, X.; Zhai, X.; Zhao, X.; Lei, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Li, W. Hyperspectral inversion of soil carbon and nutrient contents in the Yellow River Delta wetland. Diversity 2022, 14, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, B.; Mahmood, H.S.; Quraishi, M.Z.; Hoogmoed, W.B.; Mouazen, A.M.; van Henten, E.J. Sensing soil properties in the laboratory, in situ, and on-line: A review. In Advances in Agronomy; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; Volume 114, pp. 155–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawale, N.M.; Adamchuk, V.I.; Prasher, S.O.; Rossel, R.A.V.; Ismail, A.A. Evaluation of two portable Hyperspectral-sensor-based instruments to predict key soil properties in Canadian soils. Sensors 2022, 22, 2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wu, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, C.; Guo, Z.; Xu, A.; Pan, K.; Pan, X. Predicting soil moisture content over partially vegetation covered surfaces from Hyperspectral data with deep learning. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2021, 85, 989–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xie, J.; Meng, T.; Dong, H. Organic matter estimation of surface soil using successive projection algorithm. Agron. J. 2022, 114, 1944–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Liu, X. Mixture-based weight learning improves the random forest method for Hyperspectral estimation of soil total nitrogen. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 192, 106634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, S.; Sertel, E.; Roscher, R.; Tanik, A.; Hamzehpour, N. Assessment of soil salinity using explainable machine learning methods and Landsat 8 images. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 130, 103879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Fu, X.; Li, H. Inversion of chlorophyll-a concentration in Wuliangsu Lake based on OGolden-DBO-XGBoost. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jia, S.; Le, Z. Quantitative analysis of soil total nitrogen using Hyperspectral imaging technology with extreme learning machine. Sensors 2019, 19, 4355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndlovu, H.S.; Odindi, J.; Sibanda, M.; Mutanga, O.; Clulow, A.; Chimonyo, V.G.; Mabhaudhi, T. A comparative estimation of maize leaf water content using machine learning techniques and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)-based proximal and remotely sensed data. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, Q.; Shang, J.; Liu, C.; Zhuang, T.; Ding, J.; Xian, Y.; Zhao, L.; Wang, W.; Zhou, G.; et al. UAV-and machine learning-based retrieval of wheat SPAD values at the overwintering stage for variety screening. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 5166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechanec, V.; Mráz, A.; Rozkošný, L.; Vyvlečka, P. Usage of airborne Hyperspectral imaging data for identifying spatial variability of soil nitrogen content. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rischbeck, P.; Elsayed, S.; Mistele, B.; Barmeier, G.; Heil, K.; Schmidhalter, U. Data fusion of spectral, thermal and canopy height parameters for improved yield prediction of drought stressed spring barley. Eur. J. Agron. 2016, 78, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Wang, Z.; Huang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xia, H.; Cao, L. Transparency estimation of narrow rivers by UAV-borne Hyperspectral remote sensing imagery. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 168137–168153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xia, C.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, X.; Feng, G.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Q. Estimating the maize biomass by crop height and narrowband vegetation indices derived from UAV-based Hyperspectral images. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 129, 107985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Guan, K.; Zhang, C.; Lee, D.; Margenot, A.J.; Ge, Y.; Peng, J.; Zhou, W.; Zhou, Q.; Huang, Y. Using soil library Hyperspectral reflectance and machine learning to predict soil organic carbon: Assessing potential of airborne and spaceborne optical soil sensing. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 271, 112914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, B.P.; Sekhon, B.S.; Sahoo, R.N.; Paul, P. VIS-NIR reflectance spectroscopy for assessment of soil organic carbon in a rice-wheat field of Ludhiana district of Punjab. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, XLII-3/W6, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, S.G.; Teixeira, A.d.S.; de Oliveira, M.R.R.; Costa, M.C.G.; Araújo, I.C.d.S.; Moreira, L.C.J.; Lopes, F.B. Soil organic carbon content prediction using soil-reflected spectra: A comparison of two regression methods. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Elements | Water Content | Model | Original | First Derivative | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Validation Set | Validation Set | |||||||

| R2 | RMSE | MAE | R2 | RMSE | MAE | |||

| SOC/(g/kg) | 0% | XGBoost | 0.473 | 1.149 | 0.989 | 0.527 | 1.065 | 0.922 |

| RF | 0.582 | 1.074 | 0.906 | 0.598 | 1.010 | 0.867 | ||

| PLSR | 0.340 | 1.322 | 1.152 | 0.467 | 1.151 | 0.972 | ||

| 5% | XGBoost | 0.415 | 1.316 | 1.139 | 0.475 | 1.239 | 1.032 | |

| RF | 0.482 | 1.255 | 1.063 | 0.532 | 1.167 | 0.956 | ||

| PLSR | 0.295 | 1.425 | 1.219 | 0.452 | 1.244 | 1.053 | ||

| 10% | XGBoost | 0.368 | 1.346 | 1.147 | 0.457 | 1.266 | 1.065 | |

| RF | 0.403 | 1.310 | 1.124 | 0.479 | 1.251 | 1.036 | ||

| PLSR | 0.244 | 1.483 | 1.209 | 0.384 | 1.318 | 1.098 | ||

| 20% | XGBoost | 0.341 | 1.389 | 1.135 | 0.397 | 1.339 | 1.129 | |

| RF | 0.354 | 1.364 | 1.172 | 0.418 | 1.296 | 1.089 | ||

| PLSR | 0.246 | 1.481 | 1.240 | 0.373 | 1.331 | 1.078 | ||

| 30% | XGBoost | 0.227 | 1.484 | 1.249 | 0.249 | 1.455 | 1.187 | |

| RF | 0.255 | 1.449 | 1.190 | 0.311 | 1.394 | 1.145 | ||

| PLSR | 0.185 | 1.527 | 1.269 | 0.334 | 1.378 | 1.120 | ||

| TN/(g/kg) | 0% | XGBoost | 0.577 | 0.119 | 0.090 | 0.648 | 0.116 | 0.092 |

| RF | 0.606 | 0.129 | 0.106 | 0.693 | 0.114 | 0.090 | ||

| PLSR | 0.322 | 0.162 | 0.138 | 0.590 | 0.128 | 0.104 | ||

| 5% | XGBoost | 0.389 | 0.148 | 0.118 | 0.569 | 0.122 | 0.098 | |

| RF | 0.479 | 0.131 | 0.105 | 0.585 | 0.135 | 0.103 | ||

| PLSR | 0.269 | 0.171 | 0.139 | 0.539 | 0.138 | 0.110 | ||

| 10% | XGBoost | 0.311 | 0.167 | 0.134 | 0.492 | 0.134 | 0.109 | |

| RF | 0.394 | 0.158 | 0.130 | 0.516 | 0.133 | 0.112 | ||

| PLSR | 0.205 | 0.182 | 0.151 | 0.464 | 0.141 | 0.119 | ||

| 20% | XGBoost | 0.296 | 0.170 | 0.136 | 0.435 | 0.152 | 0.121 | |

| RF | 0.327 | 0.165 | 0.136 | 0.427 | 0.150 | 0.125 | ||

| PLSR | 0.196 | 0.183 | 0.154 | 0.369 | 0.156 | 0.128 | ||

| 30% | XGBoost | 0.256 | 0.174 | 0.137 | 0.397 | 0.160 | 0.125 | |

| RF | 0.308 | 0.169 | 0.136 | 0.457 | 0.150 | 0.113 | ||

| PLSR | 0.142 | 0.187 | 0.156 | 0.294 | 0.170 | 0.135 | ||

| Element | Accuracy | Data Type | Model | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TN | = 0.921 RMSE = 0.086 RPD = 2.59 | Full Spectra-OR | PLSR | Li et al., 2019 [53] |

| = 0.915 RMSE = 0.089 RPD = 2.51 | SPA-OR | |||

| TN | = 0.757 RMSE = 0.235 | OR | RF | Lin et al., 2022 [49] |

| TN | = 0.355 RMSE = 0.019 RPD = 1.245 | OR | PLSR | Pechanec et al., 2021 [56] |

| SOC | = 0.950 | FD | RF | Wang et al., 2022 [62] |

| SOC | = 0.440 RMSE = 0.070 RPD = 1.570 | OR | PLSR | Mondal et al., 2019 [63] |

| SOC | = 0.740 RMSE = 0.159 RPD = 1.780 | FD | PLSR | Ribeiro et al., 2021 [64] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qu, K.; Nie, L.; Cui, L.; Li, H.; Xiong, M.; Zhai, X.; Zhao, X.; Wang, J.; Lei, Y.; Li, W. Vis–NIR Spectroscopy Characteristics of Wetland Soils with Different Water Contents and Machine Learning Models for Carbon and Nitrogen Content. Ecologies 2025, 6, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecologies6040075

Qu K, Nie L, Cui L, Li H, Xiong M, Zhai X, Zhao X, Wang J, Lei Y, Li W. Vis–NIR Spectroscopy Characteristics of Wetland Soils with Different Water Contents and Machine Learning Models for Carbon and Nitrogen Content. Ecologies. 2025; 6(4):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecologies6040075

Chicago/Turabian StyleQu, Keying, Leichao Nie, Lijuan Cui, Huazhe Li, Mingshuo Xiong, Xiajie Zhai, Xinsheng Zhao, Jinzhi Wang, Yinru Lei, and Wei Li. 2025. "Vis–NIR Spectroscopy Characteristics of Wetland Soils with Different Water Contents and Machine Learning Models for Carbon and Nitrogen Content" Ecologies 6, no. 4: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecologies6040075

APA StyleQu, K., Nie, L., Cui, L., Li, H., Xiong, M., Zhai, X., Zhao, X., Wang, J., Lei, Y., & Li, W. (2025). Vis–NIR Spectroscopy Characteristics of Wetland Soils with Different Water Contents and Machine Learning Models for Carbon and Nitrogen Content. Ecologies, 6(4), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecologies6040075