3.1. Investigation of Titanium Discs After Friction

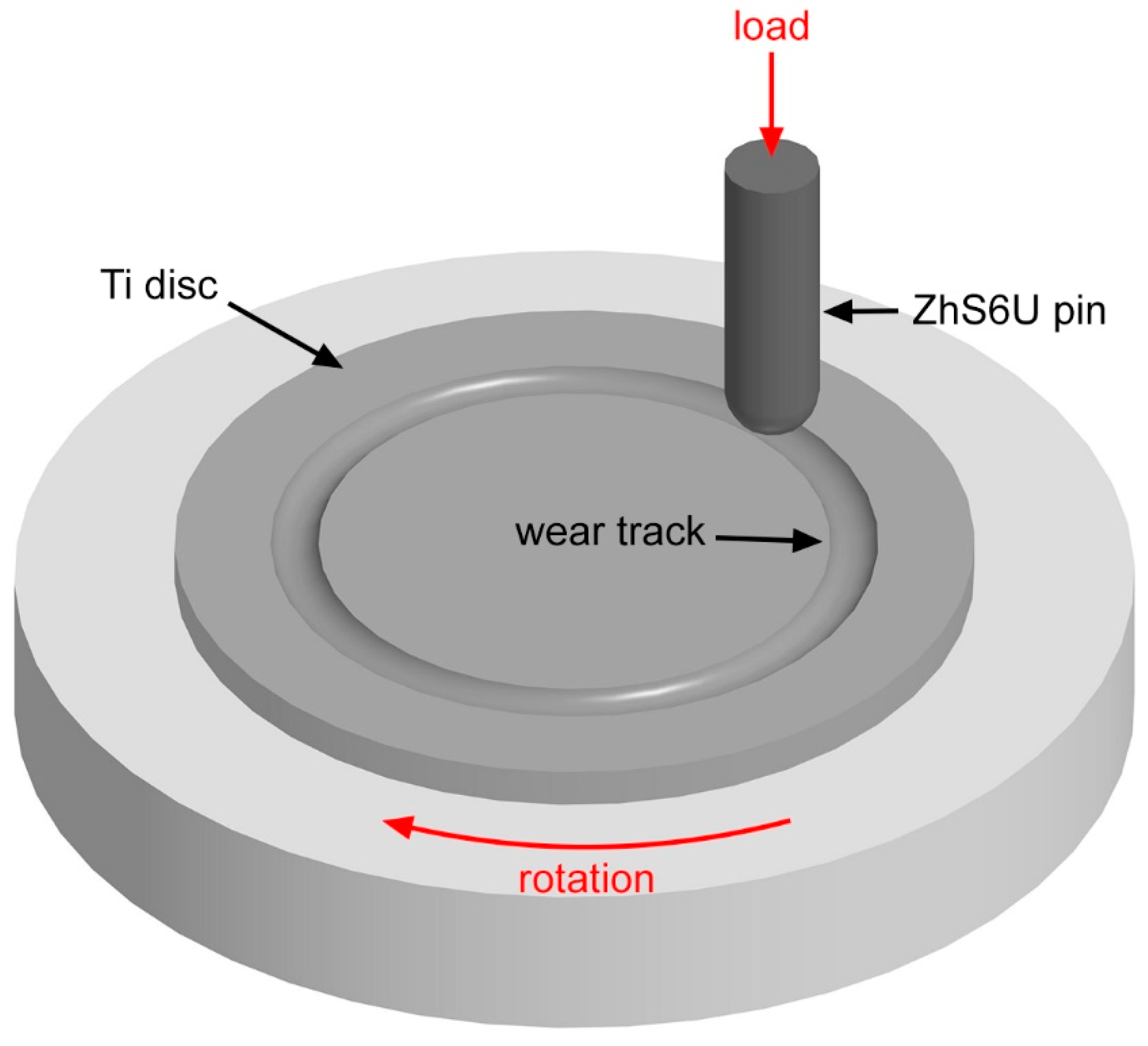

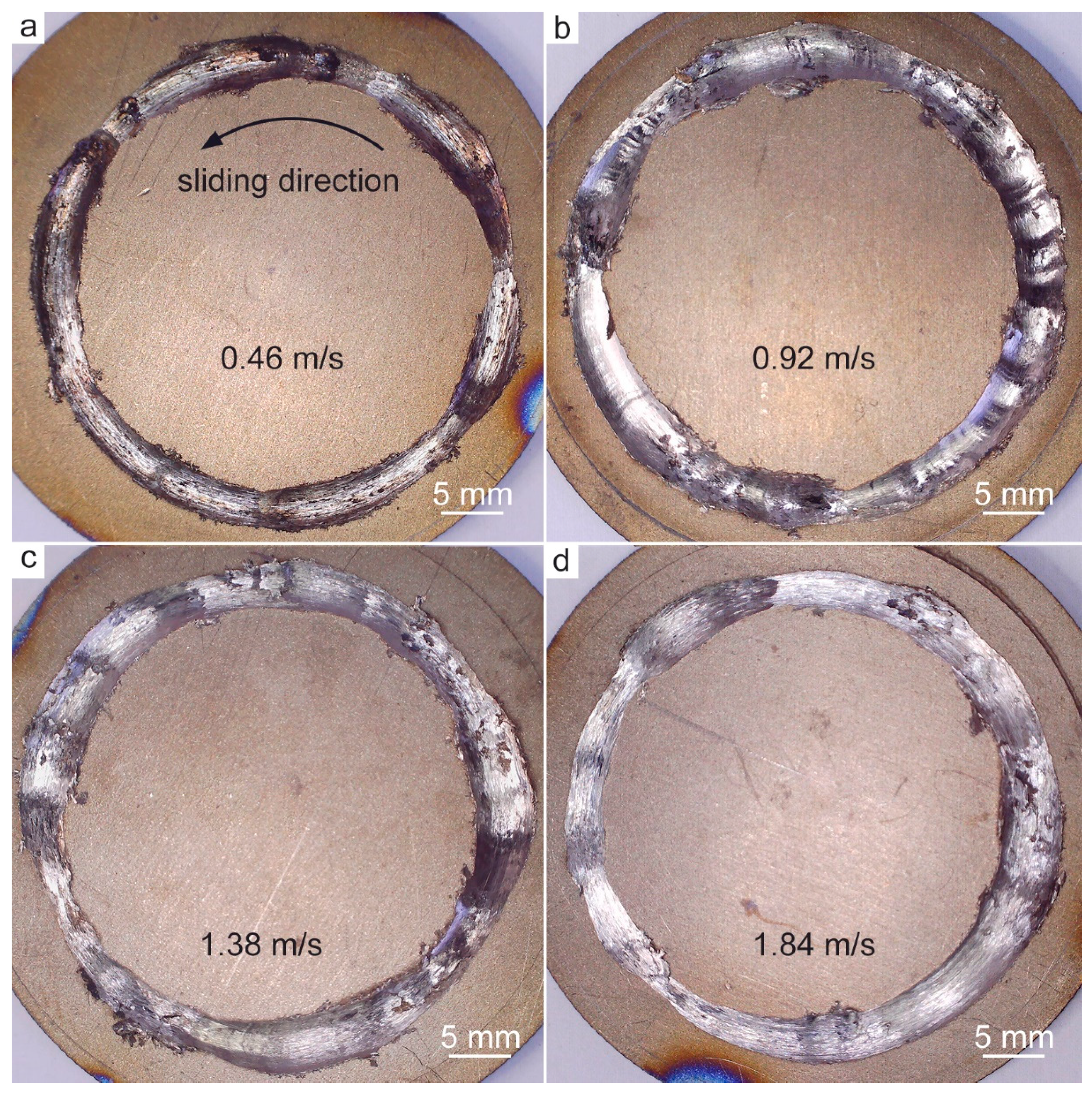

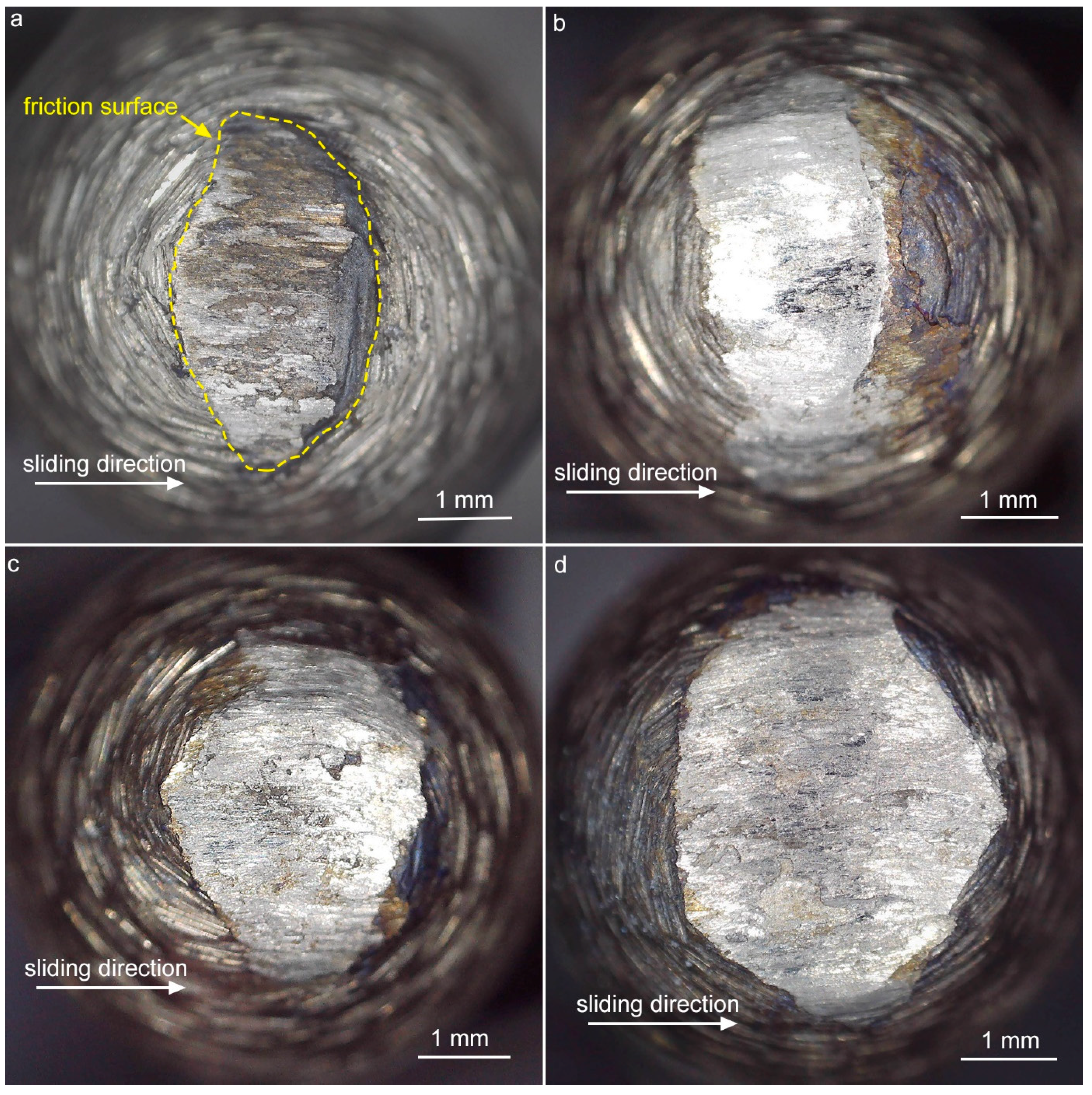

Figure 2 presents photographic images of titanium discs after friction testing. The samples exhibit visually distinguishable friction tracks characterized by circular grooves of varying width and depth. Based on these groove dimensions, three distinct section types can be identified along the friction track.

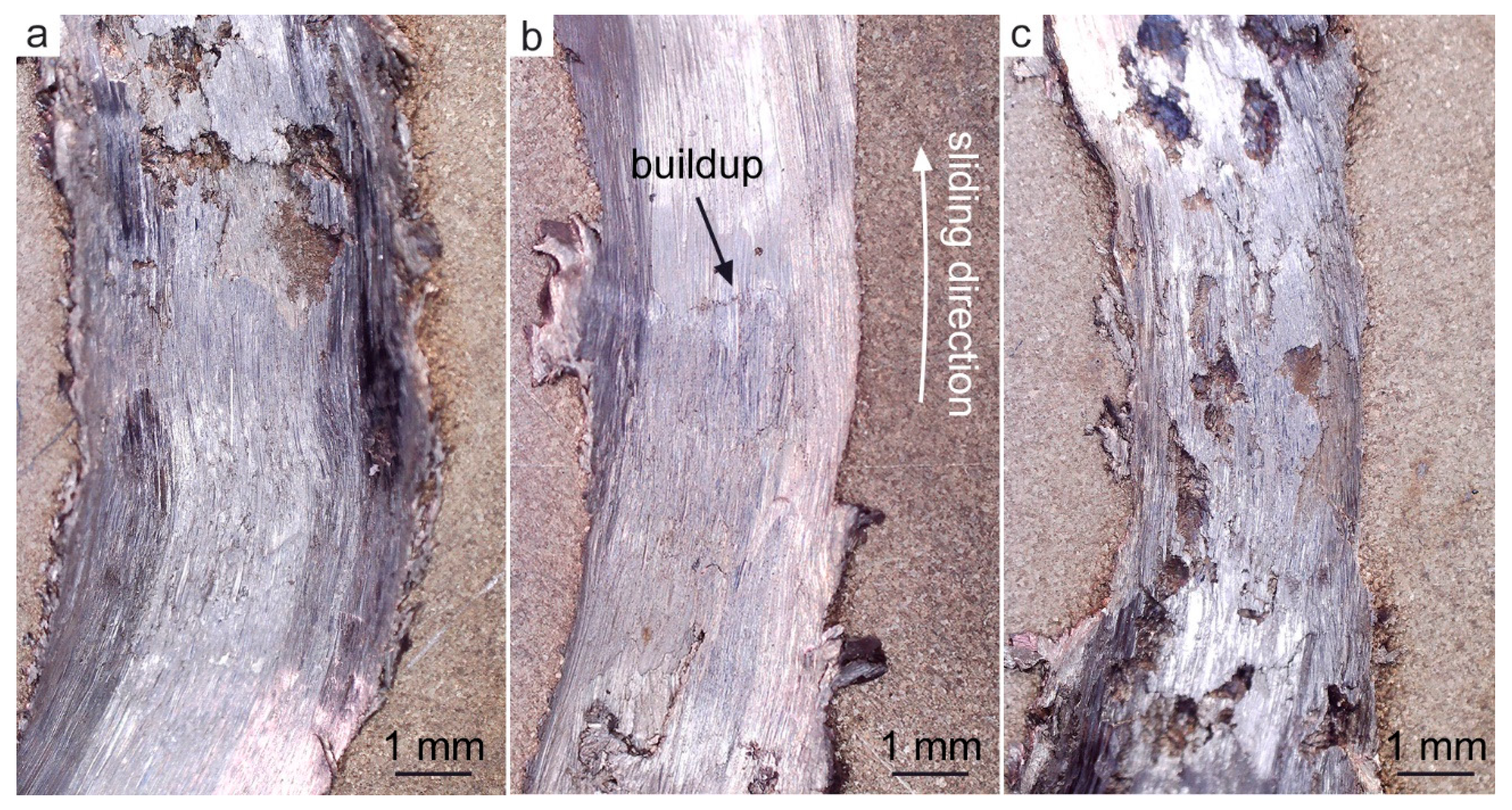

Type A corresponds to standard grooves formed by gradual wear (

Figure 3a). These sections are relatively long, spanning a disc sector angle of up to 40° or a length up to 12 mm along the friction track circumference, and exhibit the greatest and most stable width and depth. Type B regions also display large groove widths, but are characterized by material buildups, resulting in groove depths that may reach zero in these areas (

Figure 3b). These buildups are attributable to either plastic deformation and displacement of metal or back transfer of the tribolayer from the pin to the disc. Type C sections are characterized by the smallest groove width and depth; in some cases, the depth is negative, meaning the groove level is above the front surface of the disc (

Figure 3c). Due to the formation of buildups and the occurrence of tear-outs on the track during wear, the friction process is unstable and accompanied by pronounced vibrations. After a tear-out forms in one area, the pin encounters this depression during the next pass and cannot move in a straight line due to resistance from the metal, causing it to jump. Subsequently, the pin continues its motion, but its interaction with the disc material in this area is weakened due to vertical inertia, resulting in reduced wear. This repetitive behaviour leads to the formation of a Type C region. Over time, back transfer of material or plastic displacement occurs in this zone.

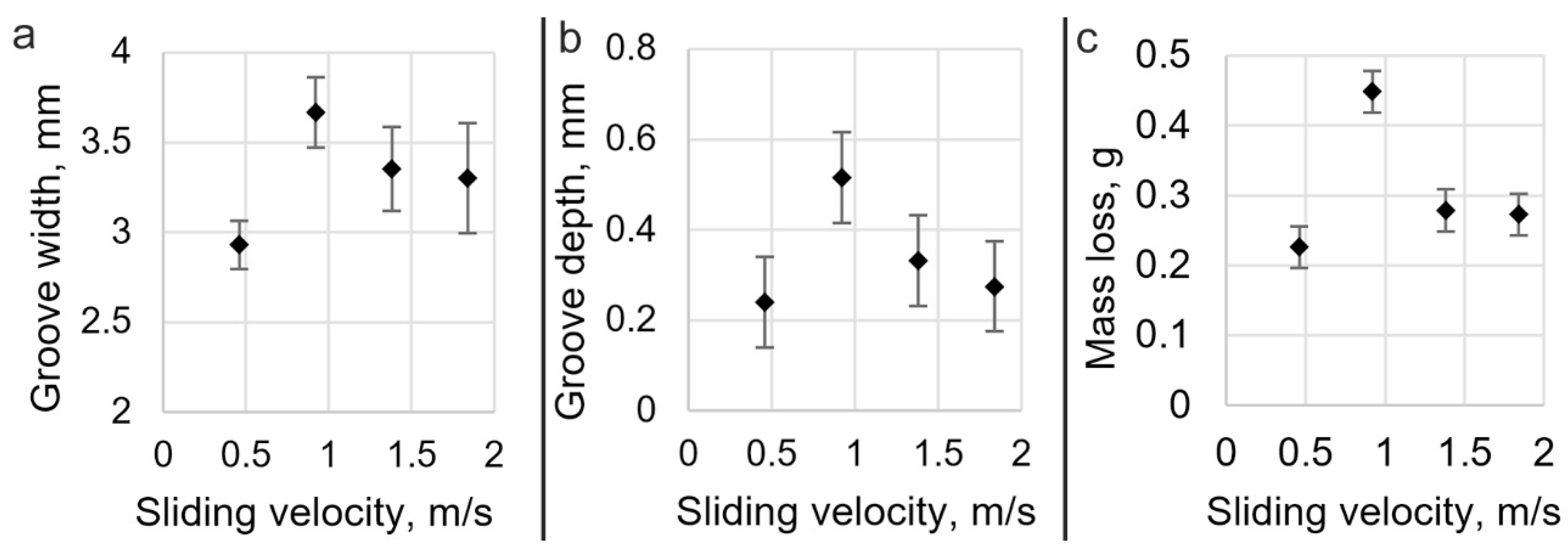

Figure 4 presents the results of measurements of the friction track width and depth, as well as the disc mass loss after friction testing. It was observed that increasing the sliding speed up to 0.92 m/s led to increased wear, while further increases in sliding speed resulted in decreased disc wear. Therefore, the maximum disc wear occurred at a sliding speed of 0.92 m/s.

Notably, the variations in all three parameters are correlated. This correlation is explained by the test geometry: since the pin has a hemispherical tip, its penetration into the disc surface leads to an increase in the friction track width, provided there is no significant wear on the pin. As shown in the following section, pin wear was relatively low; hence, disc wear caused increases in both the width and depth of the friction track. However, these parameters do not vary strictly proportionally.

Figure 5 shows graphs of changes in the friction coefficient during the experiment, as well as the dependence of the average friction coefficient on the sliding speed. It was found that at a sliding speed of 0.92 m/s, the friction coefficient was maximum, which corresponds to maximum disc wear. Increasing the friction speed to 1.38 m/s and 1.84 m/s led to a gradual decrease in the friction coefficient. Thus, the friction coefficient correlates with disc wear. It can also be observed that the friction coefficient behaves differently with increasing speed during the experiment. At a speed of 0.46 m/s, the friction coefficient decreases from 0.6 to 0.5, and after 200 m, it remains almost unchanged within the limits of fluctuations. A similar pattern is observed at a speed of 1.84 m/s: the friction coefficient decreases from 0.6 to 0.45 during the first 250 m of travel and remains relatively stable. At a speed of 1.38 m/s, the friction coefficient decreases from a maximum value of 1 to 0.6 over 500 m and stabilizes. At a speed of 0.92 m/s, the friction coefficient monotonically increases from 0.7 to 0.9 throughout the experiment, with no stabilization observed. Thus, the running-in stage is different for each speed. In general, this running-in stage is quite long. For example, in works [

7,

9] running-in took place over 50 m–150 m under similar conditions. At the same time, the coefficient of friction for Inconel 625 against Si3N4 under similar conditions was lower (0.55–0.15) [

7]. When friction occurred against GCr15 steel, the friction coefficient was comparable (0.5 at a speed of 0.5 m/s). And for friction of Nimonic 90, Rene 77, and Udimet 520 alloys against EN-31 hardened steel, the friction coefficient was much higher—about 0.9–0.7 [

12].

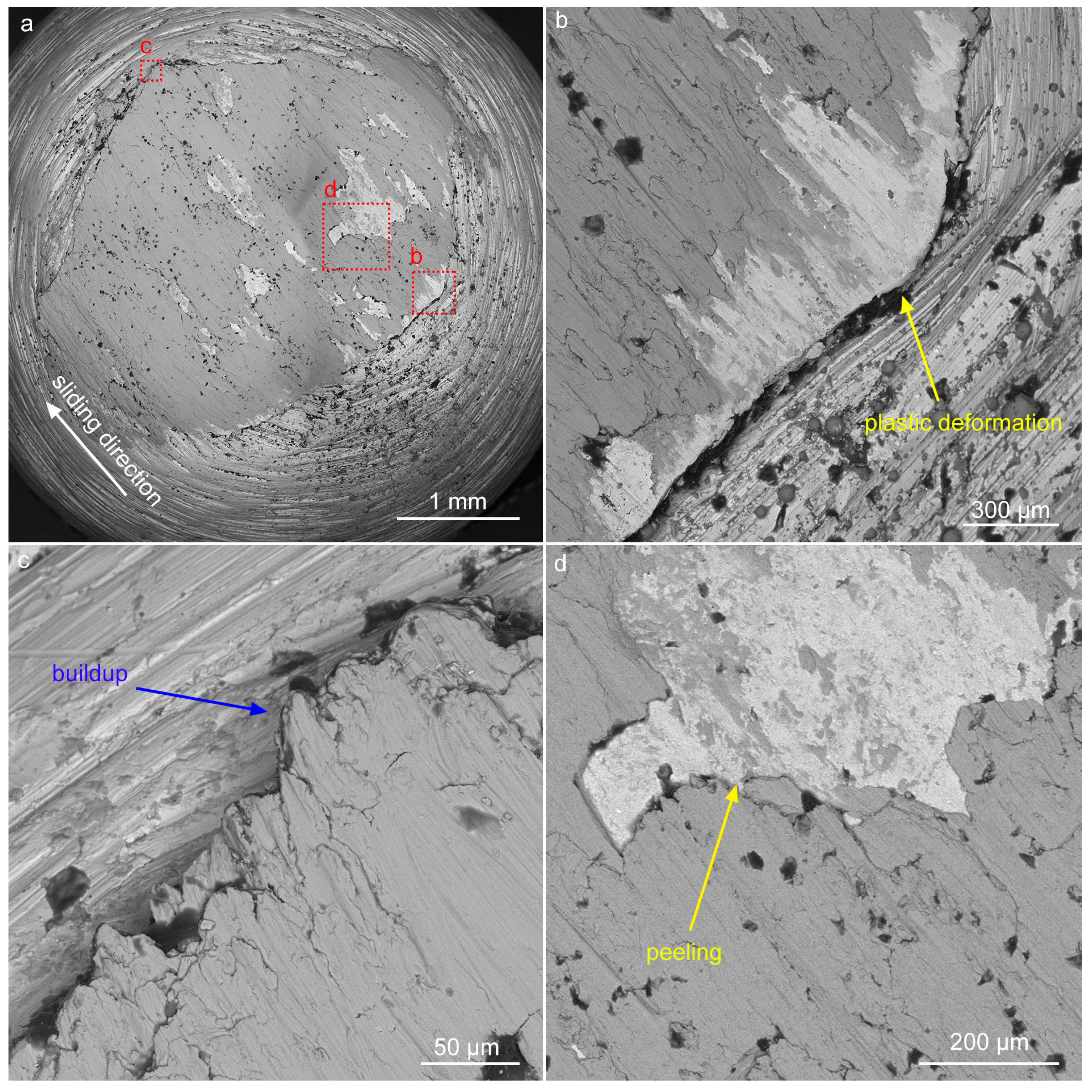

Figure 6 presents SEM images of the friction track surface of disc #3 captured in backscattered electron mode. The images reveal regions with relatively smooth surfaces exhibiting traces of plastic deformation oriented along the sliding direction. EDS analysis demonstrated that the composition of these regions closely matches that of the disc material (

Table 2, spectrum 1), suggesting that these areas experienced predominantly plastic deformation during sliding friction. In contrast, other areas on the friction surface display a highly fragmented transfer layer characterized by numerous cracks. EDS analysis of this transfer layer revealed a high oxygen content, reaching up to 11% (

Table 2, spectrum 2).

Thus, it can be concluded that during friction at the interface of the friction pair, a tribolayer is formed, consisting mainly of the disc material. The tribolayer is formed as a result of the micro-roughness deformation. Further friction is a process of this third body deformation with the heat energy release. Accordingly, the friction surfaces are in contact with the tribolayer (third body). This tribolayer is picked up by the pin and transferred back to the disc. During this process, mechanochemical oxidation of the transfer layer occurs, since the tests were conducted in an air atmosphere. In turn, oxidation leads to embrittlement of the transfer layer and the appearance of cracks. This hypothesis was suggested in [

16]. At the same time, oxidation of the transfer layer also leads to a decrease in the friction coefficient, since after transfer, the pin continues to move over the already oxidized material of the disc, which has different tribological properties. Therefore, during friction at speeds of 0.46 m/s, 1.38 m/s, and 1.84 m/s, the friction coefficient decreased until a stable state was established. Similar results were reported in [

8,

9]. In the case of a speed of 0.92 m/s, the adhesion between the pin and the disc was so high that the pin constantly came into contact with the lower layer of pure titanium, which was not subject to oxidation, and continuously wears it.

Contrasting light objects were also found on the transfer layer. EDS analysis showed an increased content of nickel, iron, and tungsten in these areas, i.e., elements that compose the ZhS6U alloy (

Table 2, spectrum 3). Thus, it can be concluded that the transfer layer contains particles of the pin, which also wear out during friction. Notably, tool debris was always observed only in the transfer layer and was not observed on the surface of pure titanium after friction. This is an important observation because it confirms the hypothesis put forward in [

15]. This paper presents the results of a study of an FSW tool made of ZhS6U alloy after titanium welding and proposes a scheme according to which friction between ZhS6U alloys and titanium forms an adhesive bond and mutual diffusion occurs. Taking into account the formation of the tribolayer, it can be said that the surface of the ZhS6U alloy interacts precisely with the tribolayer. As a result of the tribolayer deformation between the friction surfaces with heat release, the atoms of the ZhS6U alloy diffuse into the tribolayer. As a result, the surface layer of the tool is modified and then separated during friction. Wear particles form a mechanically mixed layer that remains in the weld. This scheme was partially proven because a modified layer was found on the tool, but there was no certainty that wear occurs only according to this scheme. This paper shows that this is exactly how wear occurs on the ZS6U pin. Under regular sliding friction, ZS6U pins do not wear. Apparently, the same feature is typical for friction against steel [

12]. However, when friction between DD6 superalloy and Si

3N

4 occurred under similar conditions, no mechanically mixed layer was observed, and other wear mechanisms acting, including abrasive and oxidative wear [

17].

Figure 7 shows SEM images of the friction track on disc #4 in cross section. Since wear occurs cyclically, different wear stages can be conditionally distinguished on a single cross section. After the initial stage of plastic deformation of microroughnesses and the formation of a tribolayer, shear stresses lead to the formation of cracks, which can spread from the friction surface or arise under the surface (

Figure 7b). Further, due to the action of stresses, cracks grow, the disc material breaks off, and a cavity forms (

Figure 7c).

The disc material is transferred to the pin, forming a transfer layer. Subsequently, the transfer layer breaks away from the pin and is transferred back to the disc, covering the cavity (

Figure 7d). Since the friction process also causes pin wear and oxidation, the transfer layer actually becomes a mechanically mixed layer (MML) consisting of disc and pin materials. It was found that the maximum crack propagation depth in these samples is about 60 μm. The maximum thickness of the transfer layer on the disc was also 60 μm, which appears to be critical under these conditions.

Figure 8 shows optical images of the initial microstructure of titanium and the friction track on disc #4 in cross section. The results of the microstructure analysis showed that the grain structure of the subsurface layer of the friction track was modified during friction. In its initial state, titanium has an equiaxed grain structure with a grain size of 53 ± 7 μm. As a result of friction, the grain in the subsurface layer is refined and deformed. In

Figure 8b, several areas can be conditionally distinguished: the fine-grain zone (FGZ), which is located directly at the friction surface. In this area, it was not possible to determine the grain size. This area resembles the stir zone that forms during friction stir welding [

18] and friction drilling [

19]. The thickness of the fine-grain zone reaches 60 μm. Based on this, it can be concluded that the fine-grain zone is actually MML, which was observed in SEM images. Next, thermomechanical affected zone (TMAZ) can be distinguished, in which plastic deformation of grains and partial recrystallization occur under the influence of temperature and deformation. In this area, the minimum grain thickness was 7 μm, and the thickness of the zone reaches 200 μm. Closer to the edges of the friction track, grain elongation is most noticeable.

3.2. Investigation of Pins Made of ZhS6U Alloy After Friction

Figure 9 shows photographic images of pin surfaces after friction. The friction surface shows visible signs of oxidation and adhered titanium. At speeds of 0.46 m/s and 0.92 m/s, the friction surfaces have an elongated shape across the friction direction. As the speed increases, the friction surface becomes wider. It is remarkable that in all cases the friction surface is shifted towards the front of the pin. This is due to the drag force experienced by the pin surface when it penetrates the disc material and plastically displaces the titanium.

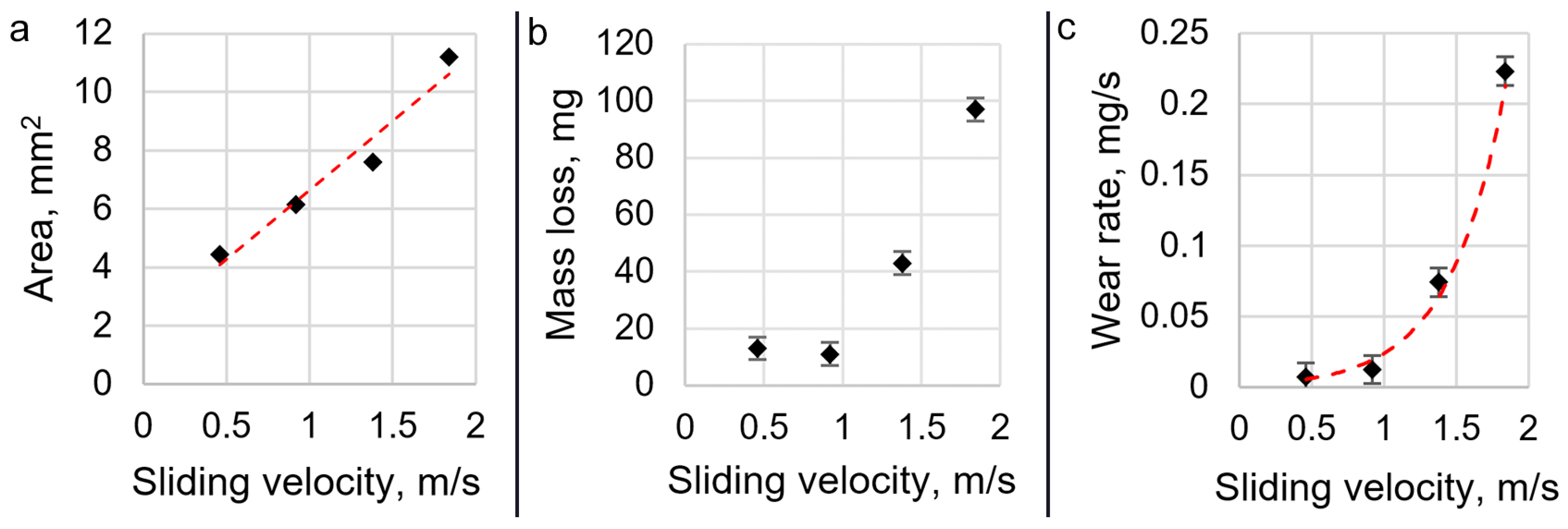

Figure 10a shows a graph of the friction surface area as a function of sliding speed. Judging by the graph, the dependence of the surface area on the friction speed is close to linear. In particular, if the graph is approximated by a straight line, the coefficient of determination

R2 is 0.9539. Based on the measurements of the friction surface area, the pressure of the pin on the disc at the end of the tests ranged from 2.6 MPa to 3.3 MPa. At the beginning of the tests, the pressure was 1245 MPa. When the friction speed increased from 0.46 m/s to 1.84 m/s, the friction surface area on the pin increased by 2.5 times. Previously, it was found that the depth of the friction track on the disc varies non-linearly depending on the sliding speed, which does not fully explain this dependence.

Figure 10b shows a graph of the pin wear depending on the sliding speed. It was found that at speeds of 0.46 m/s and 0.92 m/s, pin wear is 13 mg and 11 mg, respectively, which differs within the accuracy limits. The value of wear was determined as the difference in mass before and after the test. A further increase in the sliding speed to 1.38 m/s and 1.84 m/s increased the pin wear to 43 mg and 97 mg. Although the pins travelled the same distance during sliding, the duration of the test varied due to the different sliding speeds. Therefore, the wear rate was also calculated as the ratio of the wear value to the test time.

Figure 10 shows the dependence of the finger wear rate on the friction speed. The function takes on an exponential form and can be expressed by the following formula:

where

V is the friction velocity. The coefficient of determination

R2 for this function is 0.9966. A similar pattern was observed in [

13] at similar temperatures and speeds. However, the authors described wear under these conditions as thermal softening wear. The pattern of wear rate in friction tests of Nimonic 90, Rene 77, and Udimet 520 nickel superalloys against EN-31 hardened steel was close to linear [

12]. However, the overall wear mechanism in this study appears to be similar.

By analyzing the wear of the pin and the disc together, the linear dependence of the increase in the wear area on the pin can be explained as follows. When the sliding speed increases to 0.92 m/s, the wear of the disc increases significantly and the depth of the friction track increases. Accordingly, the pin plunges deeper into the disc and the friction area increases. A further increase in speed leads to a decrease in the depth of the friction track, but at the same time, pin wear increases significantly, as shown by mass measurements. Since the pin tip is initially hemispherical-shaped, its wear leads to an increase in the friction area. In addition to wear, plastic deformation of the pin surface occurs during friction. This also led to an increase in the friction surface area. This was most clearly observed on pin #4 (

Figure 11).

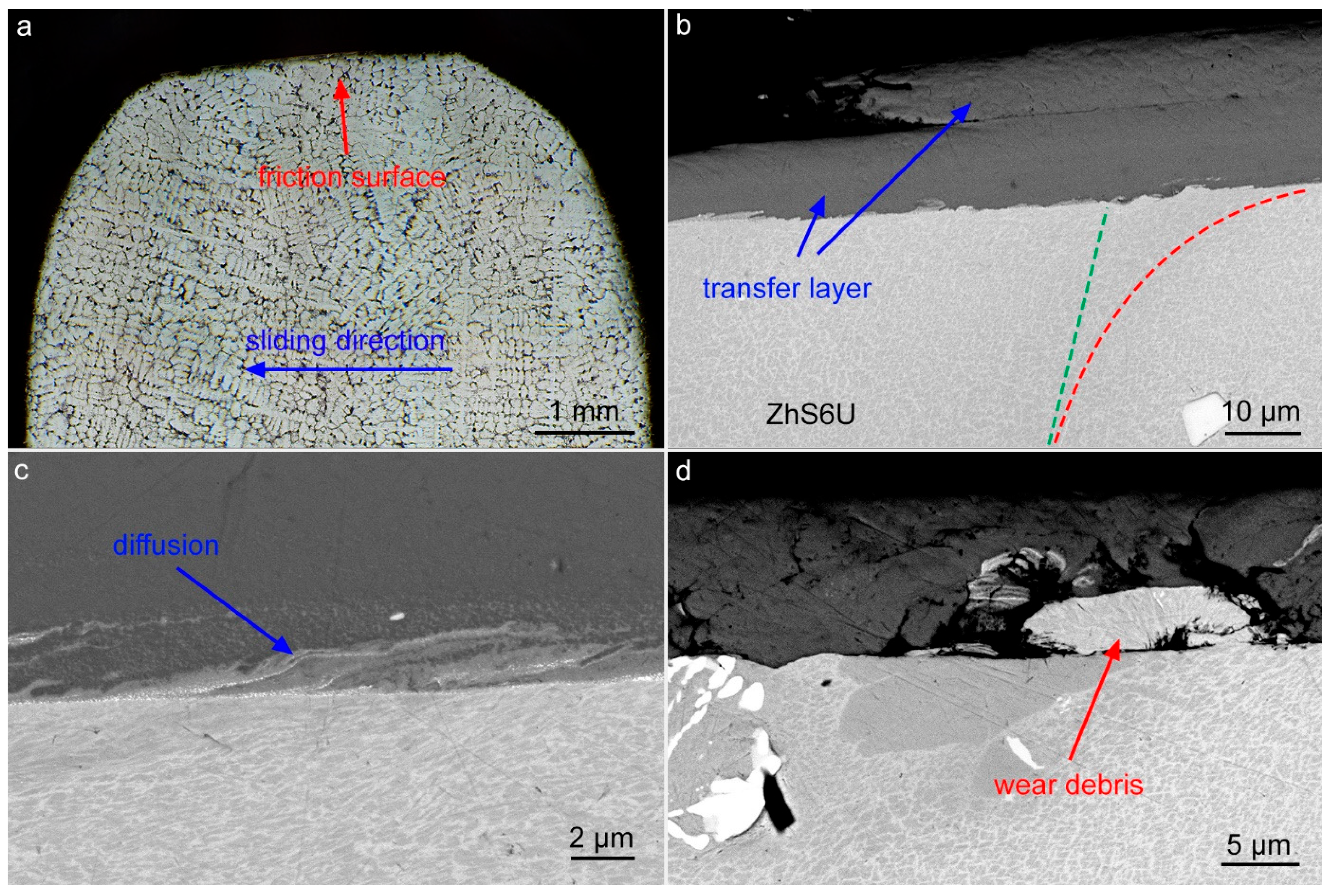

At the back edge of the friction surface, there is a ridge of ZhS6U material, which has been plastically deformed during friction. At the front edge of the friction surface, there is a transfer layer consisting of disc material. Almost the entire friction surface is covered with an adhered transfer layer with a scaly surface morphology, but there are also local areas where the transfer layer has delaminated (

Figure 11d). In addition to the areas where the tribological layer has delaminated from the pin surface, the thickness of the layer also varies, as can be seen in the cross section (

Figure 12).

Figure 12a shows a metallographic image of the structure of pin #4 in cross section. The pin material has a dendritic macrostructure, which is characteristic of the cast alloy ZhS6U. No changes in the macrostructure of the surface layer were found after friction. At the micro level, the alloy structure is represented by γ’-phase cuboids [

20]. During friction, these cuboids were plastically deformed in the surface layer in the direction of friction (

Figure 12b). The depth of plastic deformation was about 30 μm.

Several stages of pin wear can also be observed in the cross section.

Figure 12b shows the adhered transfer layer. In this area, it can be seen that the transfer layer has a complex structure and is divided into two sublayers. It can be concluded that titanium first adheres to the surface of the pin as a result of adhesion, and then the transfer layer grows as a result of cohesion.

Figure 12c shows how the pin material diffuses into the transfer layer. As a result of diffusion, the surface layer of the ZhS6U alloy weakens and breaks down.

Figure 12d shows how a particle of the ZhS6U alloy, having separated from the pin, became mixed into the transfer layer. As a result of these processes, the thickness of the transfer layer constantly changes and reaches a maximum value of 20 μm. The average thickness of the transfer layer adhering to the pin is 14 ± 4 μm.

The results obtained at this stage do not allow for the prediction of the most effective parameters for friction stir welding, as each tribosystem possesses unique properties. However, several general observations can be made. To minimize wear on the ZhS6U alloy tool, it is advisable to select a lower tool rotation speed. Increased friction speed appears to enhance the diffusion of ZhS6U atoms into the tribolayer, thereby accelerating tool wear. From the perspective of achieving high-quality welds, the friction speed should be chosen to optimize the efficient transfer of titanium to the tool and back. In this study, titanium exhibited the highest wear at a sliding speed of 0.92 m/s. Given that the wear mechanism was predominantly adhesive, this speed represents the most effective operational mode.