1. Introduction

The philosophy of seismic design has progressed to a point where contemporary structural systems can maintain their integrity and safeguard the lives of residents even in the aftermath of severe earthquakes. This achievement is primarily attributed to the distribution of inelastic deformation across specifically designed regions of structural members, or specifically designed additional members, which mitigates seismic forces. Nevertheless, sustained deformations in a traditional structure following a significant seismic event may effectively reduce the ductility capacity to withstand future earthquakes, as noted by Maffei et al. [

1], and could potentially result in progressive collapse. A study conducted in Mingora City, Pakistan [

2], concluded that over 90% of buildings fall within damage grades 4 and 5 following the 2005 Kashmir earthquake, emphasizing how a reduction in ductility capacity affects structures. Another study emphasized that as population continues to concentrate in seismically active regions, the demand for resilient structures has become a pressing matter [

3]. Prior studies have indicated that buildings exhibiting residual drift ratios exceeding 1% are not deemed safe and should be demolished [

4]. Furthermore, it is crucial for contemporary seismic design to create resilient structures that demand minimal or no repairs following a seismic event.

One of the first efforts to mitigate seismic loads was made by Watanabe et al. [

5], who designed and built a brace encased in a buckling-restraint concrete and steel tube. This is considered the first type of Buckling Restraint Brace (BRB) that brought resilience and durability to structures in Japan and opened the door for numerous other designs for metallic-type energy dissipating devices. The other major development was the design of a self-centering brace, a structural component that forces the structure to return to its original position after an earthquake. The primary configuration is a self-centering brace coupled with an energy dissipation device, which could be a viscous fluid piston, a viscoelastic damper, a friction device, a Shape Memory Alloy (SMA) tendon, or a metallic dissipator. The literature has numerous references to self-centering mechanisms, as well as different types of energy dissipating devices, when searched separately. Haque et al. [

6] built a Piston-Based Self-Centering (PBSC) brace with super-elastic SMA bars and obtained good damping results. Christopoulos et al. [

7] and Zhu et al. [

8] simultaneously combined both components in a brace featuring a friction device as the energy dissipator. Metallic dissipators have so many solitary applications in the literature, especially for U-shaped Flexural Plates (UFP)-type dissipators, which have been studied thoroughly; specifically, Baird et al. [

9] conducted an experimental and numerical study of UFP dissipators, Konishi [

10] studied the fatigue life and behavior of UFPs after extreme earthquake loading, and Jiao et al. [

11] studied the deformation capacity and hysteretic behavior of UFPs.

The UFP was first proposed by Kelly at al. [

12] and consisted of two steel plates bent about a radius, R, in the middle to form a U shape, with both ends being parallel; applying displacement to the plate ends in the opposite directions results in, firstly, the yielding of the steel at two locations, where the radius of curvature is changed from linear to curved, and secondly, the initiation of the forming of plastic regions which dissipate energy under cyclic displacement after yield activation. The depth and size of the plastic regions increase when the UFP undergoes larger displacements, and the lifetime of the device is virtually forever, given that the maximum displacement is less than πD (diameter) and the correct material is employed [

12]. In addition, the U-shaped plates can also be designed to sustain large plastic forces, displacements and therefore provide significant energy dissipation capacity by varying their thickness, width, and curvature radius. The metal plate array is economical to obtain, fabricate, and apply; once manufactured, it does not lose its strength or integrity over time, and during seismic events, it can exhibit strength, ductility, and hysteretic behavior throughout the duration of the earthquake and subsequent aftershocks. It remains resilient and durable for the duration of its service life. UFPs have been successfully employed on several occasions. Typically, they are used in breaking cladding–building connections [

9] and coupling timber shear walls together [

13]; both applications utilize a reduction in the seismic influence on structures.

Self-centering mechanisms are designed to restore both the device and the connected structure back to their center following a seismic activity by employing a mechanism to limit displacement and store seismic energy in the tendons within. The most common configuration involves installing this device in the form of a diagonal brace that spans from a floor’s column-beam connection to the corresponding one on an adjacent column line at the floor above or below. Typically, it has a core, an outer tube that moves reciprocally relative to the core, and two base plates located at both ends, which are connected by tendons or other elastic materials that store seismic energy and limit displacement. In the literature, tendon materials vary from high-strength steel cables [

14,

15,

16,

17] or SMA [

6] to Fiberglass Reinforced Plastic (FRP), Carbon Fiber Reinforced Plastic (CFRP), Basalt Fiber Reinforced Plastic (BFRP) [

18], or Aramid [

7]. When a horizontal motion occurs, this translates into a change in the brace length. This displacement is limited by an energy storage device; at the point of load reversal, the stored energy applies a restoration force that pulls the brace and the connected structure back toward its original position, and the built-in energy dissipation devices reduce the disturbance.

The idea of combining self-centering tendons with U-shaped flexural plates is not new, as this can be seen in the literature, namely by Xhahysa et al. [

18] and Mashal et al. [

19]. The novelty of the present study is focusing on a different combining technique of these two beneficial components, trying different UFP sizes, materials, and different component configurations of the brace that is applicable to steel, reinforced concrete, and precast concrete structures.

There are ductile brace configurations in the literature [

20], which dissipate seismic energy and are replaceable following a seismic event. In addition to energy dissipation and self-centering capabilities, this current study presents a further advantage of easy installation and replacement due to its relatively low weight in comparison to conventional BRBs. The presented brace utilizes only steel, which is widely available, economical, also does not have complicated parts that require specialized mechanical expertise, like viscous fluid or viscoelastic damper braces. These types of dampers are high-tech and can only be fabricated in certain countries, and therefore, are expensive to obtain and maintain. There is a risk of viscous fluid leakage from gaskets or obstruction of piston passage holes over time, potentially compromising their performance in the event of an earthquake. On the other hand, metallic dissipators, like the one investigated in this study, do not have degrading properties and maintain functional reliability over extended service life.

This study focuses on a specific configuration and utilization of U-shaped flexural plates integrated with a self-centering mechanism. As part of this study, the objective is to conduct numerical analyses and novel full-scale tests on specific configurations to examine how the independent parameters, such as post-tension (PT) force, UFP thickness, and UFP material type, influence the brace’s inherent hysteretic energy dissipation and self-centering behavior.

2. Brace Configuration and Test Setup

2.1. UFP Materials

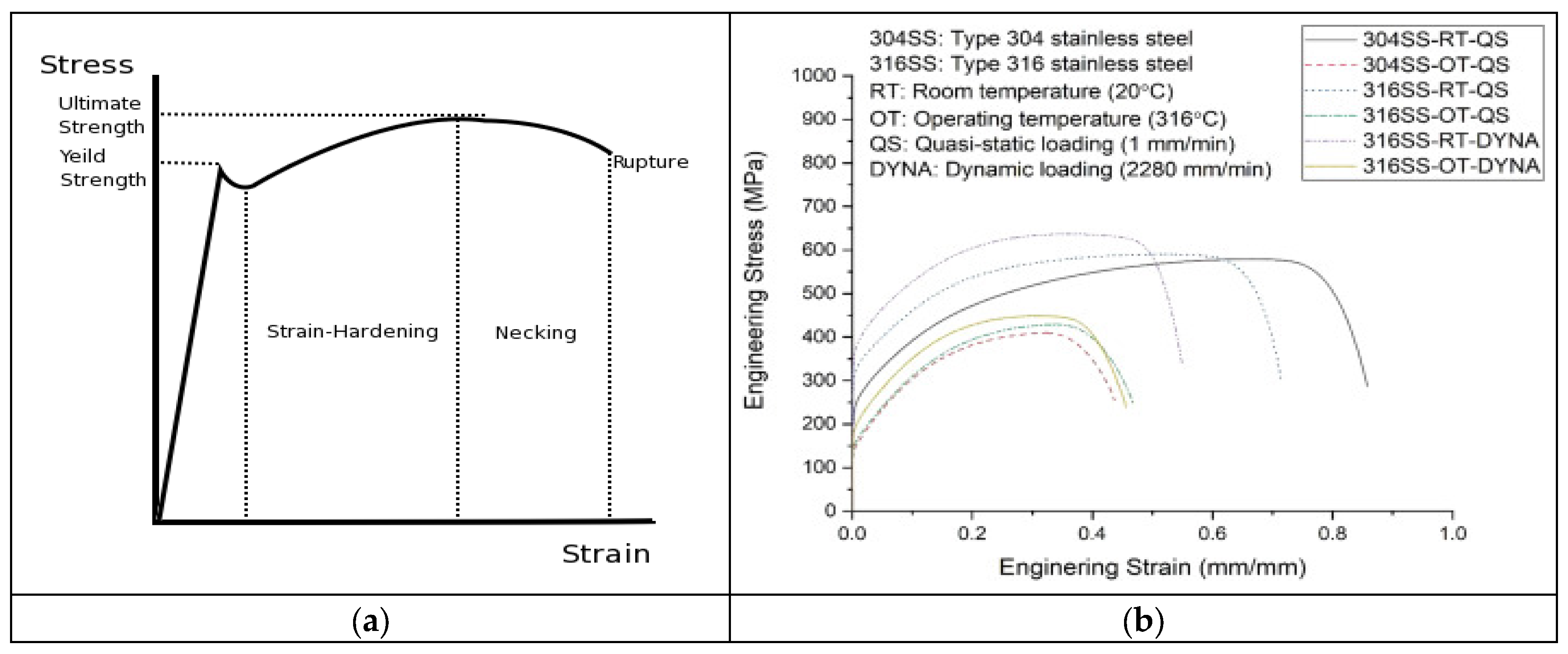

Material for UFP constitutes an important subject, as the UFPs only function in the plastic region. A material that is ductile and has an extended plastic region is preferable. Medium carbon steel alloys are suitable for this purpose; they have higher ductility and failure strain in comparison to high carbon steel. The mechanical properties of suitable materials are given in

Table 1, and the stress-strain plots for A36 and stainless steel are given in

Figure 1.

A36 (regular) steel is a medium-carbon, mild steel that allows good weldability, has a definite yield point (250 MPa), and can strain at most 10% before rupture. It is suitable to be used as a UFP plate as it provides good ductility, but poor durability performance (See

Figure 1a, below); after 10–20 cycles, it develops a localized kinking, followed by a transverse rupture and fails [

12].

Austenitic Stainless Steel, SS304, is a low to medium carbon, high alloy, soft steel that has strong corrosion resistance, excellent welding performance, high rupture strength, and displays high ductility. It has a different crystalline structure, due to additional chrome and nickel, which results in “flowing” of the steel without losing its internal coherence and consequently demonstrating very high ductility, stress redistribution, and strain hardening as the incurred stress values increase [

21]. This crystalline structure doesn’t allow the steel to have a definite yield point, as the stress redistribution starts at the early stages of loading and goes on until the rupture (See

Figure 1b, below). At the rupture, the strain rate is almost 85.8% (at 20 °C, [

20]), and the stress value increases significantly. This high ductility, high strain value at rupture is particularly useful for our purposes to employ this material in UFPs; as UFPs work to dissipate energy in the plastic region, between the material’s initial yielding and the tensile fracture point. This prolonged resistance to failure allows UFPs to bear high seismic displacement demands and increases the probability of surviving multiple seismic events without replacement and renders SS304 a good candidate to be used as UFPs.

On the other hand, A36 steel is less ductile than stainless steel and is more appropriate for use in the structural components of the brace. High carbon steel alloys are not suitable for UFPs as increasing carbon percentage elevates the yield strength and reduces the ductility, and UFPs require extra high ductile capability. A36 steel is more economical to use in comparison to stainless steel. Stainless steel is more expensive, but it is more suitable to use as UFP material, because of its superior long-term performance that will help the brace to withstand multiple earthquakes.

Welding length should be optimized to provide adequate strength, while also permitting UFPs to deform excessively and maintaining high energy absorption capacity, as these parts do most of the work.

2.2. Brace Components

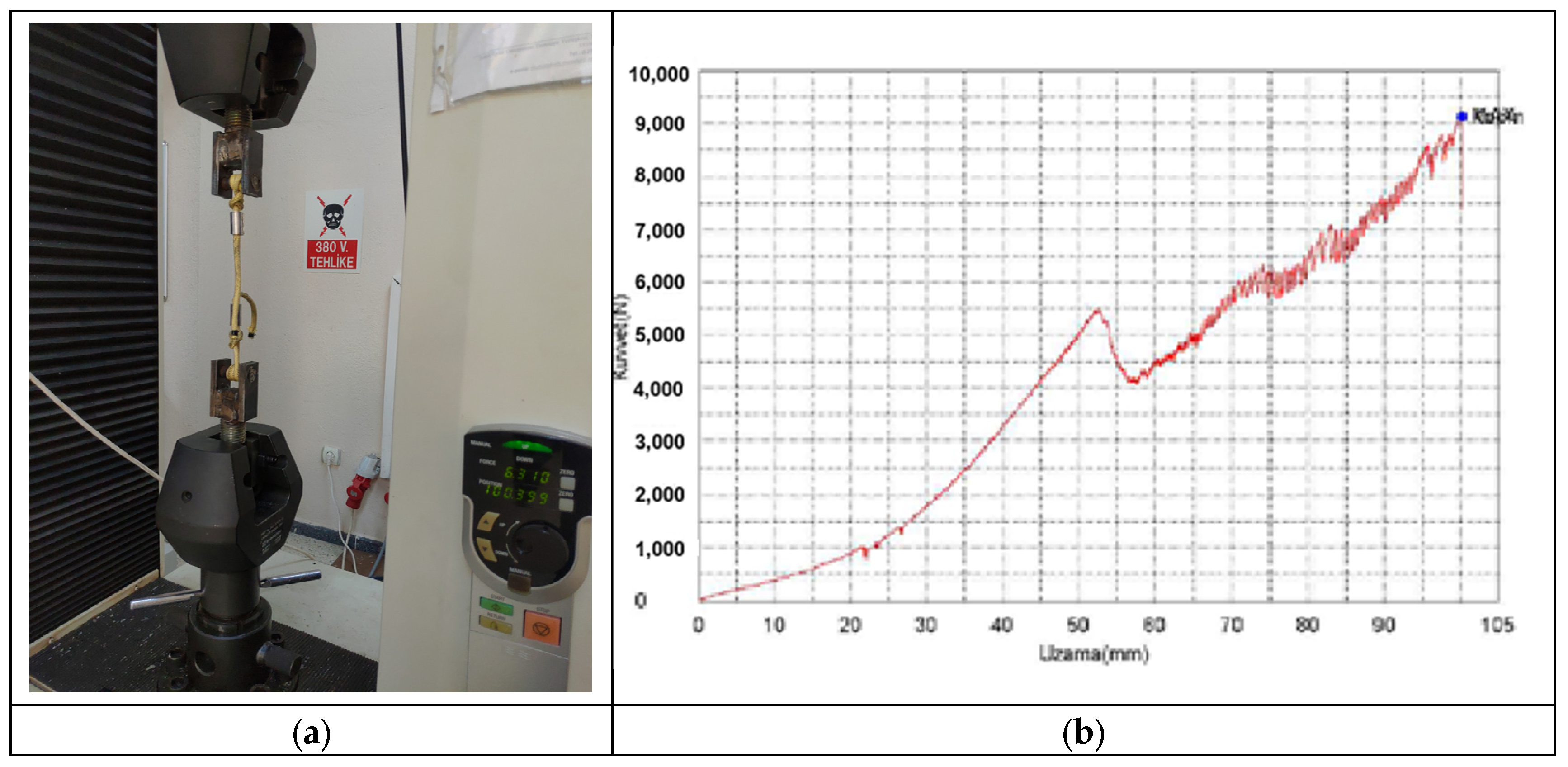

Geometrically, the brace body is 3800 mm long, which constitutes an I-beam and a Hollow Structural Steel (HSS) member. With the addition of brace support structures overall length increases to 4350 mm. The HSS member has a wall thickness of 6 mm, with some plate weldments added to strengthen for compression buckling where necessary. The I-beam used is an HEA 160 section (160 mm flange width, 152 mm height with 6 mm thick web and 9 mm thick flanges). Base plates are 30 mm thick; their size is tailored to allow correct telescopic motion of the brace. There are two configurations for post-tensioning the brace: (a) with Aramid

® tendons, (b) with steel disc-type springs and connection steel cables. Preliminary experiments were conducted to test Aramid

® tendons and their connection terminals,

Figure 2a. However, in all tests, tendons developed a shear rupture and failed at the location where Aramid

® tendons were coiled over connection terminals. The force-displacement plot of this configuration is provided in

Figure 2b, which shows a drop at 5.5 kN, which denotes premature shearing of some strands in the tendon; this drop renders the usage of the tendon unsafe for tests, due to losses in the tendon’s overall cross section. Moreover, the 5.5 kN force level is low in comparison to the PT forces (12, 25, 35 kN/tendon) that are required during the tests. The plot clearly shows that this configuration is unreliable and cannot be used as a PT tensioning material in our experiments.

As a result, the Aramid

® material is deemed unsuitable for use as a tensioning element for the brace, and instead the steel spring configuration is adopted in full-scale laboratory tests. For the Aramid

® tendon configuration, the tendon diameter is derived; they are bound by the two base plates at both ends. Each tendon requires a terminal assembly that connects the tendons to the base plate. The terminals are fabricated from steel plates that have a rod in the middle for tendon connection. The terminal body is welded to 35 mm diameter threaded rods that go through the base plates that are present at both ends of the brace, and tension adjustment is made through the rod and a nut resting on the base plate. The steel disc-spring configuration is the same, except the spring canister is placed in the middle of the brace and is connected with four steel cables to their respective terminals to make tension adjustments. There are guides that force the brace to move in a symmetrical fashion inside the HSS member. The force transfer connections are designed to have larger moments of inertia under compressive loading, and their rated capacity is 800 kN. The components of the brace are shown in

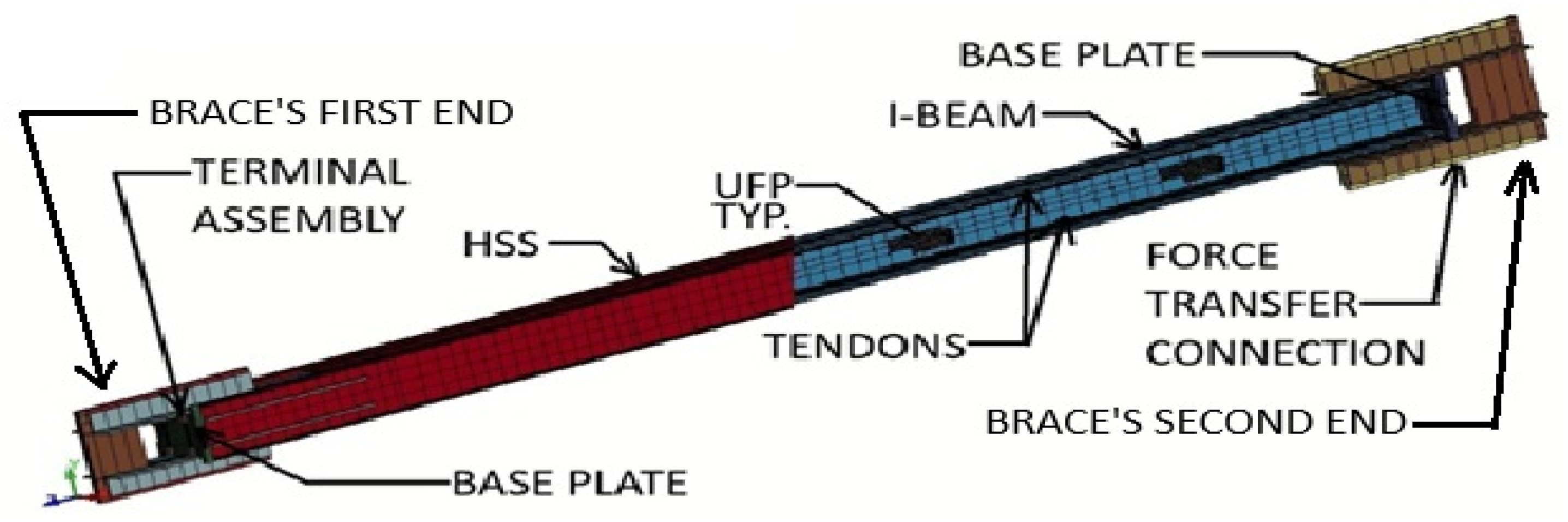

Figure 3.

The steel disc springs are pretensioned with a hollow cylinder jack by hand pumping it until a desired force level is indicated on the gauge. Once the target force is reached, the tensioning nut is tightened to transfer the PT force to the base plate. The pump valve is opened to relieve the pressure and retract its extender to dismount the hollow cylinder jack and pretension the other spring.

The configuration of a UFP self-centering brace is comprised of a W-section inserted into the tube steel (Hollow Structural Steel—HSS) of equal length, 8 UFP plates welded on both sides of the I-beam web and the inner face of the tube using 8 mm thick and 90 mm long welds along both UFP legs, top and bottom. Two base plates are located at each end of the brace. These base plates are connected with steel cables and terminal assemblies. Force transfer connections are required to connect to the structure, with one transferring forces to the HSS member and the other to the W-section. The permissible length difference between the W-section and the HSS can be 5 mm maximum. During fabrication, one end can be aligned, while the gap can be accumulated at the other end, and the force application holes must be 1 mm larger than the 80 mm diameter pin, in order to prevent motion lag during the tests. By means of cross-sectional alignment, the W-section should ideally be right in the middle of HSS’s cross section, but misalignment up to 5 mm along the transversal axes within the plane of the cross section is acceptable.

The working mechanism of the brace is illustrated in

Figure 4 below. When the compression force is applied to the first end of the brace, that is transferred to the first end of the W-section (green), which moves the W-section and the steel plate (purple) at the second end of the brace to the right. Similarly, the compression force applied to the second end of the brace acts on the second end of the tube steel (red), moves the tube steel and the steel plate (purple) that is at the first end of the brace to the left. Both purple plates at the ends of the brace are pushed in opposite directions, applying tensile force to the tendons. The tensile force applied to the first end of the brace acts on the first end of the W-section (green), moving the brace and the steel plate (purple) at the first end of the W-section to the left. Similarly, the tensile force applied to the second end of the brace acts on the second end of the tube steel (red), moving the tube steel and the steel plate at the second end of the brace to the right. Both purple plates at the ends of the brace are pushed in opposite directions, applying tensile force to the tendons.

The mechanism outlined above always results in applying tension to the tendons in any case, regardless of the loading scenario, see

Figure 4. In this way, the energy accumulated in the tendons through displacement is utilized to return the brace to its initial position. Meanwhile, the UFP plates attached to the tube and W-section act as dampers and dissipate energy as the two structural components move in opposite directions; the system forms a hysteretic damper.

During the design phase once the basic geometrical requirements and constraints are defined, the numeric model of the brace was designed, built, and solved in LS Dyna (2023R2), a numerical analysis software. Through the results of the preliminary analysis, the section properties are adjusted to check and optimize the brace’s global and element-wise strengths, where resultant cross sections and final configuration are finalized through this iterative process. Another restraint was the actuator’s capacity, which was 400 kN, and all braces section properties and total reaction force are optimized for 800 kN. It was understood from the analysis that only the UFP plastic force is not a defining factor, as UFPs continuously deform and reduce its share in the total force amount, meanwhile the spring’s force share is increased. After the numerical model is optimized, supplementary analyses were run to see the effects of PT force, plate thickness, and material changes. These additional simulations were used to prepare the mindset for full-scale laboratory experiments.

2.3. Specimens and Adaptation Members Fabrication

The length of each specimen is selected to be 3800 mm, excluding connection sections, where the HSS member (200 × 200 × 8 mm) and the I-beam (HEA160) have equal lengths and cut from 6-m stock length profiles. Following cutting, the HSS receives a welding opening that aligns with UFP’s free leg, 10 mm holes for running sensor cables out of the profile and 140 mm × 600 mm cut at both sides to place the spring that applies the Post-Tension (PT).

UFP plates are cut to 40 × 350 mm strips and bent into a U shape in a hydraulic press after heat processing is done. Each UFP is then welded to the web of the I-beam at given distances, with the weld length intentionally limited to maintain free motion of the leg. Then the I-beam is inserted into the HSS member with the help of a crane, and UFP legs are aligned with precut holes for welding them on the inner side of the HSS member. Next step is to run steel cables in the I-beam’s left and right cavities and attach them to terminals at both ends and both sides; run the terminal through two holes in base plates at both ends. Base plates that are 30 mm thick and have 2 holes per plate are at both ends. Finally, the force transfer structures are welded to both ends, one to the I-beam and the other on the HSS member. The HSS member must be notched to allow welding of the force transfer structure to the I-beam. Finished products are painted to minimize effects of corrosion and stored until testing. Braces are separated into two sets for testing different mechanisms.

For the first set, two different types of materials (Regular and stainless steel) were prepared to test the brace configuration without the PT force. For the second set, two different UFP thicknesses (6 and 8 mm) are used to test the effects of plate thickness, and 2 types of materials—regular steel and stainless steel—are employed to test the material aspects. With this combination, there are 6 fabricated specimens; each brace is installed in heavy-duty springs and tested for a single post-tension load, ranging at 60, 100, and 140 kN. All braces, adaptation pieces and miscellaneous parts are manufactured and supplied by Kaya-Tech Steel Manufacturers located in Izmir, Turkey.

The experimental investigation of braces were carried out at the Structural Engineering Laboratory at Dokuz Eylul University. The laboratory is equipped with a wide range of advanced testing equipment and instrumentation, enabling comprehensive evaluation of structural systems under both quasi-static and dynamic loading, including bridge crane, electric winches, hydraulic actuator, and hydraulic pumping unit.

The capacity of the test frame in the laboratory is 150 tm and does not have any built-in peripheral parts to accommodate brace testing, so the adaptation elements must be built. Adaptation pieces are comprised of one tower support, one toe support, and a center buckling support. Tower support has two IPE160 pieces positioned on the left and right, with cross bracings connecting them; the top of the support left-hand side is connected to the brace with an 80 mm diameter solid steel pin, and the right-hand side is connected to the 500 kN actuator with a 30 mm base plate with 6 bolts. The toe support is built from plates and houses a 1000 kN compression/tension load cell, which measures the diagonal forces on the brace. The toe support allows adjustment of the brace installation angles from 15 to 45 degrees, made with a horizontal axis. Fabricated in 3 parts, shipped to the lab, and assembled in place with the load cell embedded at the center of the toe support.

2.4. Test Setup

The complete experimental setup is shown in

Figure 5 below. The test was conducted in a planar configuration constrained to the Y–Z directions. The hydraulic actuator applied cyclic forces along the Z-axis, thereby inducing controlled deformations in the brace. To replicate realistic building conditions, both the toe and tower’s support sections were fully fixed against movement in all directions. Both the tower and toe support are arranged so that the brace and the load cell remain colinear throughout the test. This alignment ensured that bending moments were not introduced on the load cell, which might affect the force reading. The support system was designed to allow only axial lengthening and shortening of the brace in-plane while prohibiting lateral translation of the brace’s top end.

2.5. Sensor Details and Layout

During the experimental program, a comprehensive instrumentation scheme was employed in order to accurately capture the mechanical response of the brace under cyclic loading. Various types of sensors were utilized, namely Linear Variable Differential Transformers (LVDTs) for high-precision displacement measurements, Load Cells (LCs) to record axial forces, string potentiometers (SPs) for monitoring displacements over longer distances, and Strain Gauges (SGs) were installed on UFPs and steel components to measure localized strain development. The layout and locations of all sensors are presented in the instrumentation drawing provided in

Figure 6.

Strain gauges were strategically placed on U-shaped Flexural Plates (SG-1 through 8) to capture the strain development on their curved sections, the I-beam web (SG-I group), and the tubular steel brace (SG-T group) to monitor localized strain development in the respective element, while an additional gauge on the spring canister (SG-Spring) recorded deformation of the self-centering mechanism. A dummy gauge (SG-Dummy) was used to correct for temperature-induced strain variations. The servo-hydraulic actuator, equipped with an integrated load cell (LC-Actuator) and displacement sensor (LVDT-Actuator), controlled the cyclic loading, while a secondary load cell (LC-Toe) and LVDTs at the toe support monitored axial force and potentially detect and correct the toe support motion. Global brace displacement was tracked using the string potentiometers (SP-Brace, SP-A0, SP-A2). Data was collected through three 8-channel acquisition systems (24 total channels) at a 4 Hz sampling rate, with gain values calibrated per sensor type. This configuration enabled precise generation of force–displacement and strain–deformation relationships critical for evaluating the brace’s energy dissipation and self-centering performance.

Actuator Load Cell’s resolution is 0.1 N, and was calibrated to 200 kN; Toe Load Cell’s resolution is 0.01 N, and was calibrated to 50 kN; all LVDT’s resolutions were 10 − 4 mm, and all strain-gauges were used to measure strain levels, where their operating range was from 0.001 to 4400 micro strains.

2.6. Loading Protocol

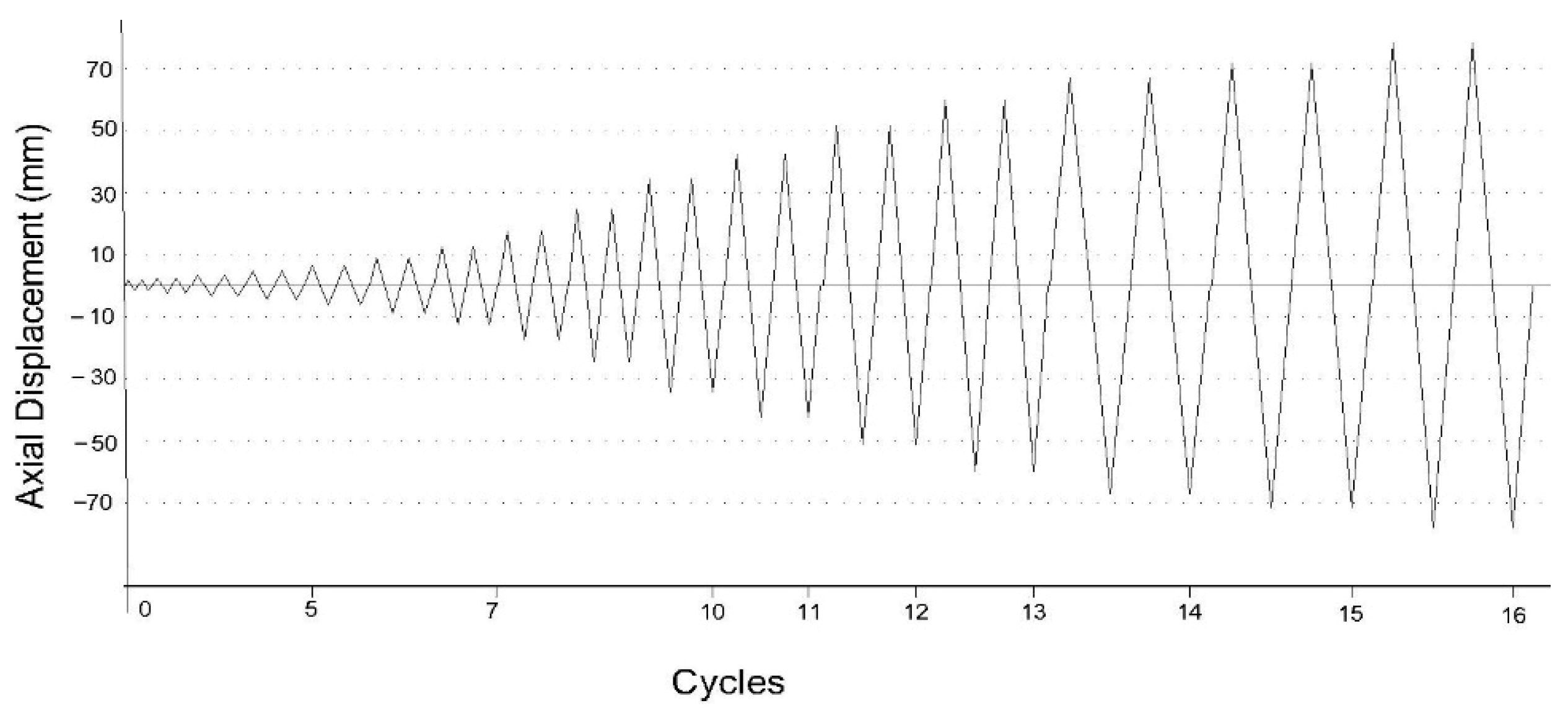

The loading protocol followed FEMA 461 [

22] guidelines for developing quasi-static, cyclic displacement-controlled testing plan. According to FEMA 461, developing a test program begins with a preliminary identification of the target damage states, and it must define the required number of specimens on which the specific loading history to be applied. A critical phase is the design of the test setup capable of appropriate load simulation and the proper replication of all important boundary conditions. This is supported by the identification of key response parameters and a detailed instrumentation plan to measure them. All aspects, including specimen details, setup, and instrumentation, must be detailed in drawings. Finally, the program must establish a clear test schedule to ensure the objectives are achieved in a timely and cost-effective manner. As per the loading protocol, the test parameters were defined as follows: (1) displacements increased by 40% per cycle, (2) each repeated twice, (3) reaching the target displacement at approximately the 10th cycle. Since the brace capacity (>800 kN) exceeded the actuator’s maximum load, the specimens were not tested to failure. Instead, quasi-static tests were carried out in the Structural Engineering Laboratory of Dokuz Eylul University using a 500 kN (400 kN nominal) hydraulic actuator with a ±200 mm displacement capacity. The target diagonal displacement was set to 45 mm (1.2% diagonal displacement), corresponding to an interstorey drift level of 1.86%. The loading protocol is shown in

Figure 7. It is important to mention that this loading protocol is for the actuator, which is facing the brace and any positive movement would translate as compression forces on the brace and vice versa.

3. Tests and Test Results

Brace tests were carried out by varying UFP plate thickness, material, and post-tension (PT) load. This study focuses on two cases: one without PT and another with 100 kN PT force (60, 140 kN were also studied). The tested brace consisted of a 3800 mm HSS and I-beam connected with eight SS304 UFP plates, each 40 mm wide with a 78 mm bending radius. For comparison, the only differences were UFP thickness and PT level: 6 mm plates without PT and 8 mm plates with 100 kN PT.

3.1. Braces Without Post-Tension Force

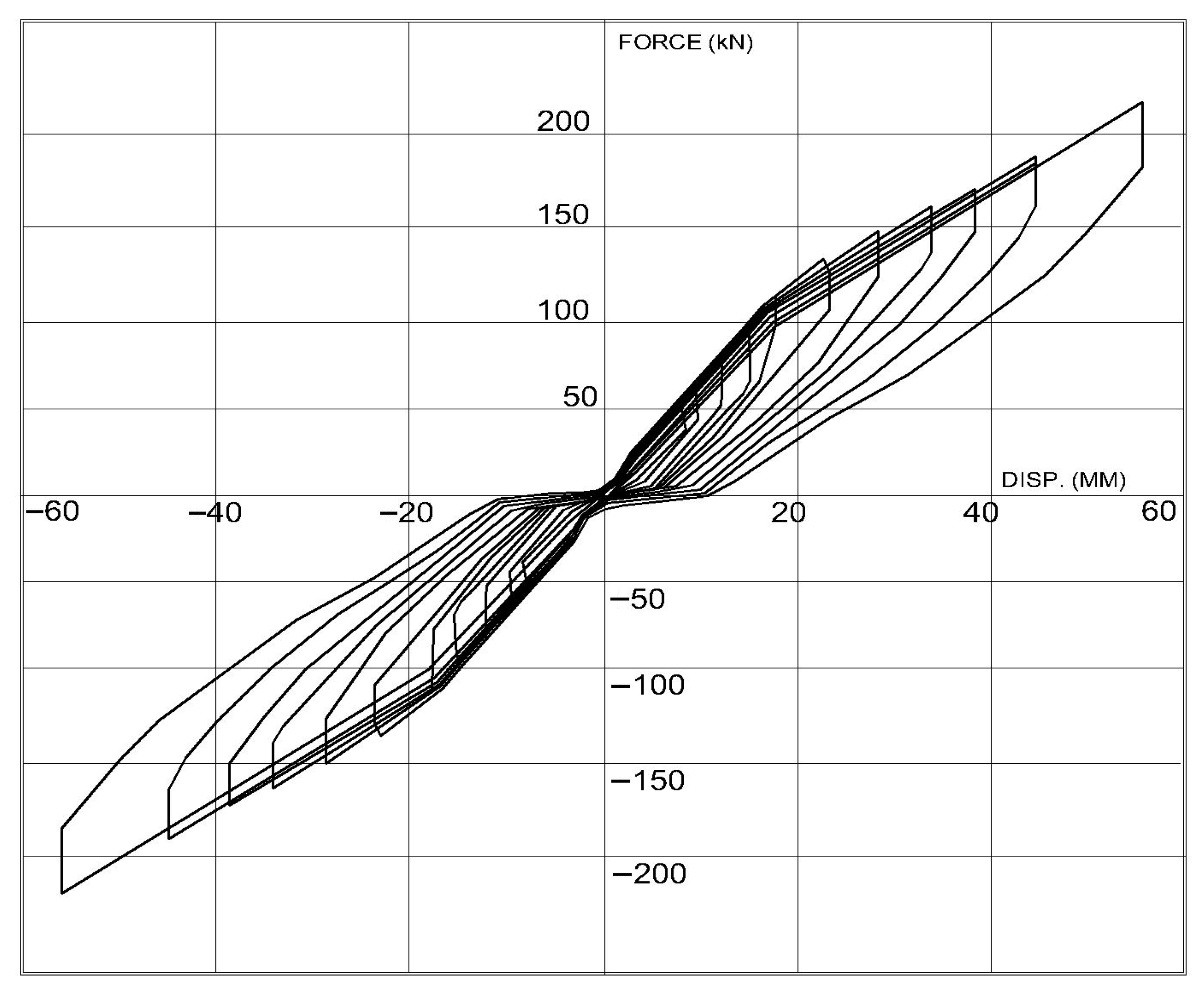

Here, a brace having 8 count, 6 mm thick stainless-steel UFP plates with zero post-tension force (

Figure 8) is discussed. As shown in

Figure 9 (positive displacement imposes compressive forces on the brace), the force–displacement plot corresponding to the brace without post-tensioning indicates that the brace behaves in a manner characteristic of a conventional metallic energy dissipator. At the initial stages of loading, when the imposed displacements are relatively small, the brace demonstrates a noticeably steep stiffness response. This behavior arises because the system is just being activated, and only localized regions of the U-shaped Flexural Plates (UFPs) are undergoing this limited yielding. Within this early range, the structural response is dominated primarily by elastic behavior, accompanied by minor localized plasticity that provides the initial onset of energy dissipation. This behavior arises because the system is just being activated, and only localized regions of the U-shaped Flexural Plates (UFPs) are undergoing limited yielding.

As the imposed displacement amplitude increases, the UFPs are driven further into the plastic response domain, and the overall stiffness of the brace begins to decrease. This reduction in stiffness is directly attributable to the accumulation of plastic deformations within the UFP plates. During load reversals, a cyclic phenomenon is observed: at the beginning of the reversal, the stiffness of the UFPs appears temporarily elevated because of the restoration of elastic deformations. However, as the reversal continues, the stiffness declines again as previously developed plastic deformations are gradually undone, and new plastic strains are introduced in the opposite direction. This alternating process highlights the dissipative mechanism of UFPs, which convert inelastic deformations into absorbed energy across successive cycles.

The yield of stainless-steel UFPs occurs at a displacement level of 9 mm, in which there is a response force of 14 kN, and after yielding, the test continues until 52 mm of displacement with an increase in force, up to 57 kN (values read from

Figure 9). The increase in force is a function of displacement; however, after a force level is reached, it is limited by the geometry of the UFPs. This large range of operation indicates a significant reserve of strength beyond the initial yield point. Stainless steel alloy has a yield stress of approximately 200 MPa and an ultimate tensile strength close to 600 MPa, providing a favorable combination of ductility and strength. Importantly, throughout the entirety of the test, none of the stainless steel UFP plates experienced fracture or local failure. This is attributed to the exceptional metallurgical characteristics of SS304 stainless steel, particularly its crystalline structure, which facilitates the redistribution of localized stress concentrations, thereby enabling the plates to sustain large plastic deformations without rupture.

3.2. Braces with Post-Tension Force

Tests were performed on a brace specimen having 8 count, 6 mm stainless-steel UFP plates subjected to a post-tensioning (PT) force of 100 kN, and

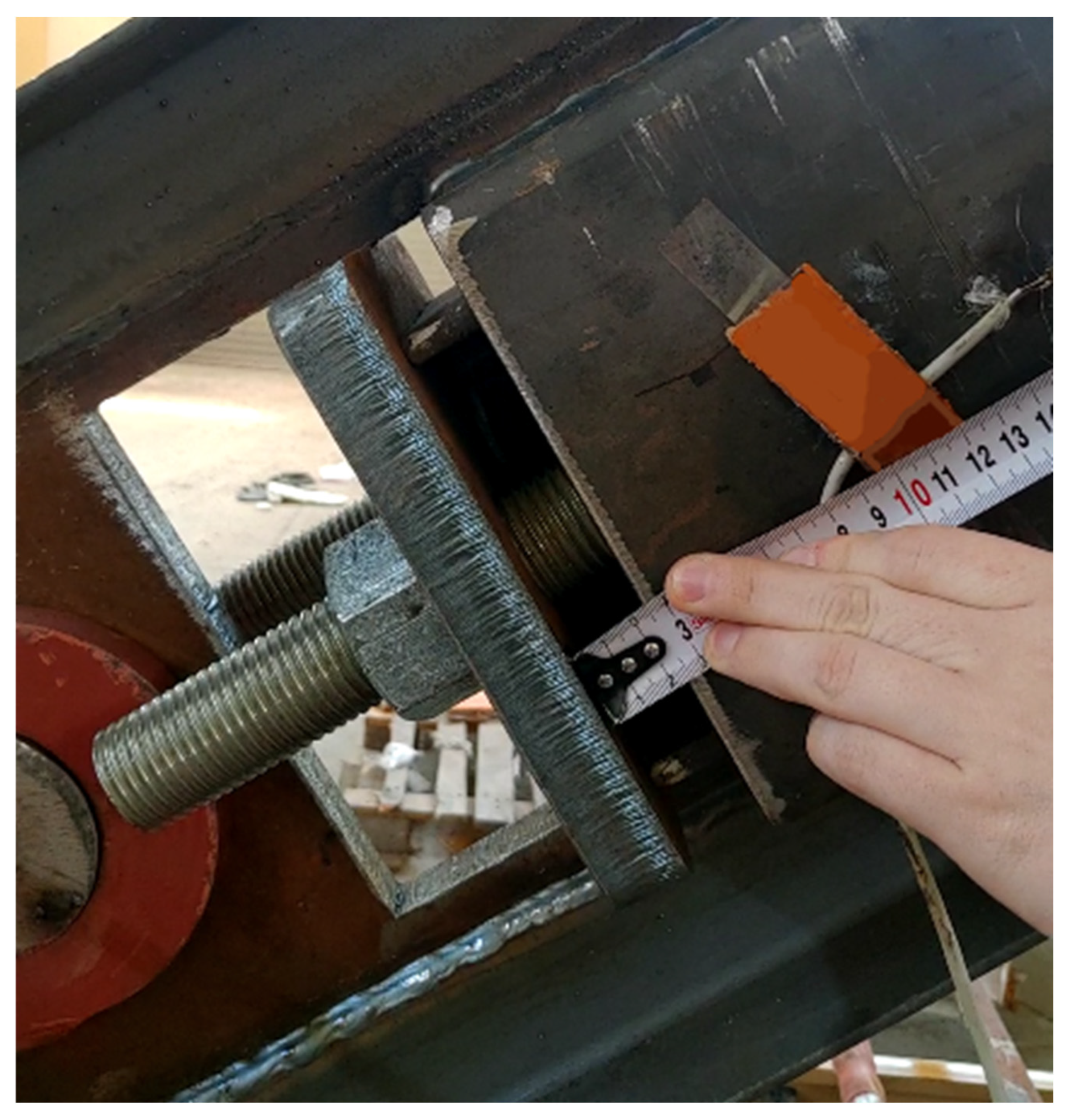

Figure 10a shows a snapshot from the test.

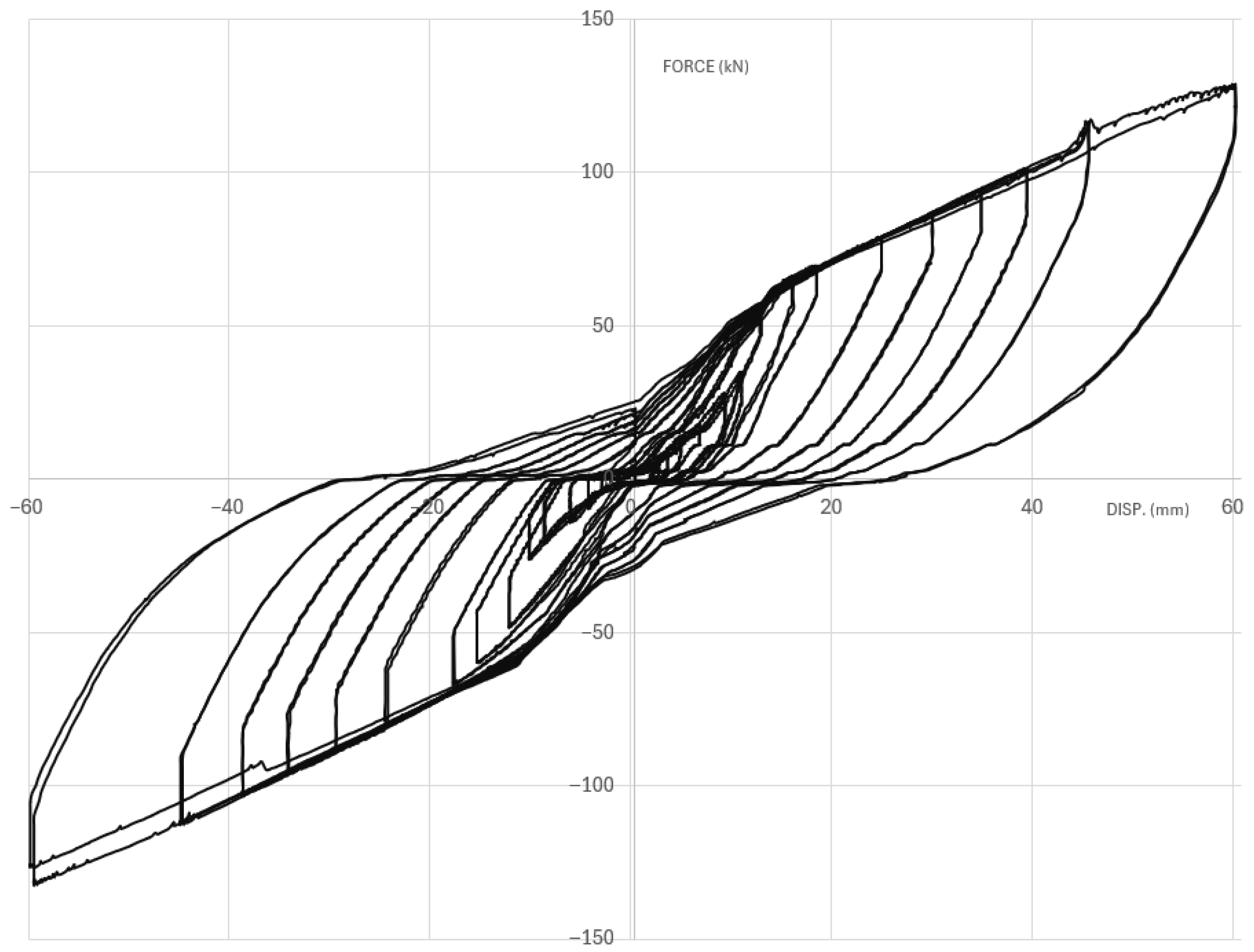

Figure 11 presents the experimentally obtained force–displacement response of the brace. The plot demonstrates the characteristic hysteretic flag-shaped behavior that is typically associated with self-centering bracing systems, which is the positive hysteretic portion (the plot that is at the positive side of the x-axis) is pushed towards the positive-y direction, and the negative is pushed towards the negative-y direction. In order to achieve a more pronounced separation between the positive and negative hysteretic branches, a higher PT force would be required. For this specimen, two high-capacity steel springs (

Figure 10b) were employed to provide the self-centering functionality. Each spring possessed a stiffness of approximately 4.3 kN/mm and was initially tensioned to a force of approximately 50 kN using a hydraulic hand pump. This preload corresponded to an initial compression of approximately 11 mm per spring, thereby establishing the baseline post-tensioning condition prior to cyclic testing. The test was conducted until the spring’s maximum displacement range, which was 55 mm, after post-tensioning was applied.

Figure 12 shows the gap formed between the base plate and the end of the brace when the brace was being displaced by 35 mm.

A key observation from the experimental results is that the stiffness of the loading cycles remains nearly parallel up to load levels of approximately ±110 kN (

Figure 11). This behavior is directly related to the presence of the 100 kN PT force, which dominates the response in this range. The PT system provides significant resistance to axial brace movement, effectively stiffening the system until the applied force exceeds the PT threshold value. Once this threshold is surpassed, the UFP plates begin to undergo flexural deformation, leading to a reduction in the overall stiffness. At this stage, the brace response is governed by the combined stiffness of the compressed springs and plastic stiffness contribution of the UFP plates. This transition highlights the cooperative mechanism of the self-centering brace: the springs maintain recentering capability, whereas the UFP plates provide hysteretic energy dissipation through their inelastic deformations.

As the imposed cyclic displacements increase, corresponding to higher drift levels, a gradual reduction in stiffness is observed (

Figure 11). This softening effect results from the accumulation of large plastic deformations and material degradation in both the UFP plates and the springs. This effect is known in the literature as pinching effect under seismic loading.

During larger displacement cycles, the unloading portion of the force–displacement plot exhibits a pronounced immediate drop in restoring force. This is attributed to the elastic recovery within the spring elements, followed by a slower recovery associated with plastic deformations in the UFP plates. The distinctive shape of the unloading branches reflects the dual role of these mechanisms, where the elastic springs provide rapid initial recovery and the UFP plates contribute to delayed plastic restoration. It is also noteworthy that residual displacements remain evident at the points where large cycles return to the zero-force axis. These offsets, reaching values as high as 11 mm, indicate the accumulation of permanent plastic deformations within the UFP plates despite the presence of self-centering springs. Such findings emphasize the delicate balance between post-tensioning force, spring stiffness, and UFP plasticity in shaping the overall performance of the brace.

It is noted that the stiffness of the brace is dropping as the deformations in all members, especially the UFP plates, increase towards the end of the test, where the extremely high displacement cycles are located.

Figure 13 shows an immediate drop in the force in the last negative cycle, which cannot be recovered. This figure also shows the effects of low PT force. This brace was tested with a 60 kN PT force and consequently, is able to provide lesser separation between positive and negative cycles in comparison to the brace with 100 kN PT force (

Figure 11). Due to the PT force being low, UFP plastic recovery cannot be completed until the brace force reaches zero. As a result, remaining plastic recovery is achieved with displacement driving back the brace forcefully until it is complete, and UFPs start elastic and then plastic deformation for the negative cycle.

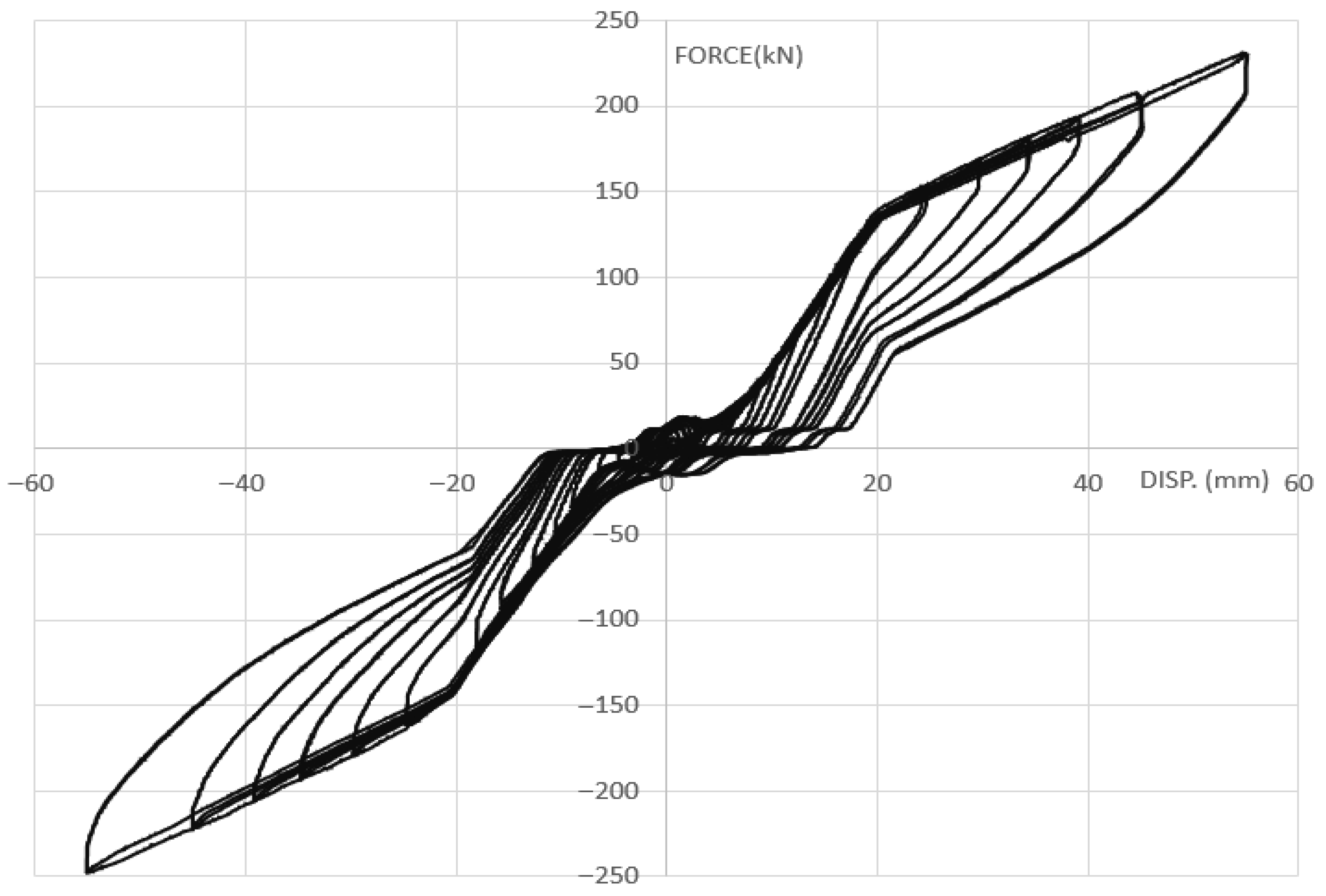

Theoretically, if the PT force is sufficiently high, it will provide sufficient separation such, that the positive and negative portions of the cycles completely recover, and there is still PT force reserved to pull the brace back to its center. The best plot to show this behavior is shown in

Figure 14. In this figure, energy dissipation portions are well separated, and the excess PT force pulls the brace back to its center after the UFPs’ plastic recovery is completed at approximately 22 mm (in the positive cycle). This elastic recovery is performed strictly by the PT force that is left in heavy-duty springs, as can be seen by the recovery stiffness being similar to the stiffness corresponding to the initial loading path. It is noted that the force-displacement curve stiffness drops when it passes approximately ±150 kN to a lower value, as the PT force is exceeded and the combined stiffness of the UFPs and springs comes into play. A summary plot, which includes an overlay of the hysteresis loops, is shown in

Figure 15. The overlay shows the benefit of PT force clearly, by means of pushing positive and negative loops apart and improving the elastic and plastic loading stiffnesses; the 60 kN plot is not included due to its plot being close to zero PT force.

The braces have fabrication and assembly imperfections; there are inevitable length differences and alignment issues between the HSS and I-beam, and gaps between the base plates and profiles. These fabrication issues cause an imperfect self-centering mechanism, resulting in force or displacement slips in the force-displacement plots. As the reaction force reaches near-zero force levels, there are large displacements covered until reaching the zero-displacement point; these total plastic deformations are due to imperfect brace construction not being able to provide adequate stiffness. Travel is required until structural members arrange themselves in a stronger position and are able to provide higher stiffness, which allows the UFP plates to start dissipating energy. The force-displacement plot shown in

Figure 14 highlights these issues, especially in all loading cycles at the vicinity of zero displacement. The fluctuations of the curves until a steady high stiffness is reached are due to these imperfections. This particular brace had a 7 mm length difference between the W-section and HSS, and because both the tension and compression plots show imperfections, we can conclude that the W-section and HSS members were aligned in the middle.

Another important contribution of the PT force is its ability to reduce residual deformations and enhance self-centering performance. This effect is illustrated in

Figure 16, which compares the residual displacement levels of the braces with and without the PT force. The brace without PT exhibits a residual displacement of ~33 mm at zero force, indicating significant permanent deformation. In contrast, the brace with a 100 kN PT force demonstrates a markedly improved recentering capability, with the residual displacement reduced to only ~9 mm. This comparison clearly demonstrates the effectiveness of the PT mechanism in restoring the brace toward its original position, thereby minimizing residual deformations and improving the overall self-centering capability of the system.

3.3. Effects of UFP Material Change

Experiments were conducted to investigate the behavioral changes of braces built with UFPs made of stainless steel and regular steel. In both configurations, the braces are equipped with 8 mm thick UFPs with 140 kN of post-tension loads, and the actual force-displacement diagrams obtained from both tests are superimposed in the same graph for comparison purposes (

Figure 17). The force-displacement plot stiffness drops when it passes approximately ±150 kN to a lower value, as the PT force is exceeded, and the combined stiffness of the UFPs and springs are now the governing stiffness. The experimental test results clearly highlight the distinct behavioral differences between the two materials when subjected to cyclic loading. The data obtained show that regular steel UFPs consistently reach higher maximum force levels compared to UFPs made of stainless steel. However, regular steel UFPs demonstrate a slightly greater energy absorption capacity, as evidenced by the larger hysteretic loop areas obtained during the tests, indicating their ability to dissipate seismic energy through plastic deformation. In terms of stiffness, UFPs with regular steel exhibit a slightly higher initial stiffness, whereas stainless-steel UFPs have a slightly higher post-yield stiffness, which contributes to improved resistance against moderate-to-high displacement demands. Most importantly, especially for high displacement levels, stainless-steel UFPs displayed a significantly better recovery from plastic deformation, with low residual displacements, which improved the self-centering capability compared to UFPs made of regular steel. In addition, it is a known fact that stainless steel has a significantly longer lifetime in comparison to regular steel. This is also shown with this test program, as the braces with regular steel samples, UFPs started to break towards the end cycles (cycles 14 through 16); in half of the tests, UFPs made of regular steel failed by rupturing. These experimentally validated findings emphasize the complementary strengths of both materials, underscoring the importance of material selection in the design of seismic energy dissipation and self-centering systems. Both materials exhibit similar force levels given that there is a considerable difference between their yield strengths.

3.4. Effect of Plate Thickness

Another parameter that was investigated was the UFP plate thickness and its effect on the response force and energy absorption characteristics. The UFP plate’s plastic force was derived by Kelly et al. [

12] as follows:

where b is the plate width,

t is the plate thickness, D is the curvature diameter, and σ is the effective cyclic stress. As shown in Equation (1), the plastic force developed in the UFPs is directly proportional to the square of the plate thickness. Kelly further refines this relationship by defining cyclic stress as a function of the yield stress

, scaled by an overstrength factor typically ranging between 1.45 and 2.15, which reflects the material and geometric nonlinearities in the plate section. Consequently, according to the formula above, increasing the thickness of the UFP plates produces a pronounced increase in both the force and energy dissipation capacity. This behavior arises from the fact that the flexural strength of UFPs is governed by their section modulus, which scales with the square of the thickness. As the thickness increases, the UFPs are able to sustain significantly higher loads and undergo larger plastic deformations before failure, which directly enhances both the structural strength and the amount of seismic energy dissipated.

Based on the test results investigating the effect of UFP thickness (

Figure 18), even though the thickness increases, the plastic force does not increase as expected.

Figure 18 shows 6 and 8 mm thick UFP plates’ force-displacement plots superimposed. As can be seen in the tension cycle, there is a 22% increase in force, whereas the increase, calculated using Equation (1), should be approximately 77%. Moreover, the force increase in the compression cycle is only 9%. This is suspected to be due to brace fabrication and assembly imperfections, which affect structural members, that is, HSS and I-beam, causing them to develop local buckling where they touch the base plates, and UFP plates buckling at their welding locations, and at some locations where there are stress concentrations.

While thicker UFP plates improve the lateral resistance and enhance energy absorption efficiency, they also increase the brace stiffness, which may influence the system-level behavior, such as drift demand, force distribution, and potential for damage concentration. Thus, although thickness is a powerful design parameter for tuning the performance of UFP braces, it must be selected by considering the balance between increased energy dissipation, desired stiffness, and system-level seismic response. These findings underscore the central role of plate thickness not only in controlling the strength and ductility of individual braces, but also in shaping the overall seismic response of structures employing UFP-based energy dissipation systems.

3.5. Energy Dissipation Characteristics

Following the completion of the test program, a detailed energy absorption analysis was performed for the brace specimens with a 100 kN PT force and the one without PT force. This analysis was performed by systematically calculating the energy dissipated during each loading cycle. Specifically, the positive and negative areas of one complete cycle enclosed within the hysteretic force–displacement curves were numerically integrated cycle-by-cycle, thereby quantifying the cumulative energy absorbed by each brace within the entire testing sequence. The calculated absorbed energy values are then plotted against their corresponding displacement levels on the same figure for both specimens (

Figure 19).

The results of this analysis reveal that at lower displacement levels, the presence of post-tensioning provides a clear advantage in terms of energy dissipation. The pre-compressed springs contribute to additional restoring forces that interact with UFP plates deforming, thereby enhancing the overall energy absorption capacity of the brace at low displacement levels. This effect demonstrates that PT mechanisms can be particularly beneficial in scenarios where the structure is subjected to small-to-moderate relative floor drifts, as they enable the brace to engage more efficiently and dissipate energy earlier in the response cycle.

However, as the imposed displacement levels increase, the difference in the energy absorption capacity between the braces with and without PT forces becomes less pronounced. At higher drift levels, the dominant mechanism of energy dissipation is governed by the large plastic deformations of the UFP plates themselves, which tend to dominate the contribution of the system providing the PT force. Consequently, the energy absorption characteristics of the two brace configurations converge, indicating that while post-tensioning improves energy dissipation characteristics at smaller displacements, both systems exhibit comparable absorption performance under larger displacement levels (or demands). These findings highlight the dual role of PT systems: enhancing early-stage seismic energy dissipation and improving self-centering behavior, while simultaneously at the same time illustrating that the inherent plastic response of UFP plates remains the primary driver of energy absorption under large displacement cycles.

To sum up the force–displacement and energy dissipation characteristics of the brace with and without PT force are summarized in

Table 2. The table compares the same parameters at two different displacement levels to emphasize the PT force and displacement’s effect at the system level. At a displacement level of 45 mm, the brace without PT exhibits little force (47.22 kN), whereas the brace with PT force reacts with 3.8 times higher force. In contrast, the dissipated energy values are within a closer range; the brace with 100 kN force consumed 7% more energy than the brace without PT force. When a smaller displacement level (8.8 mm) is selected, the trend reverses; the plastic force values of the braces with and without PT force are similar, whereas the energy dissipation of the brace with PT force is five times greater than that of the non-PT specimen. Residual drifts were reduced by approximately 72% and 69% at the 45 and 8.8 mm displacement levels, respectively, improving the self-centering performance.