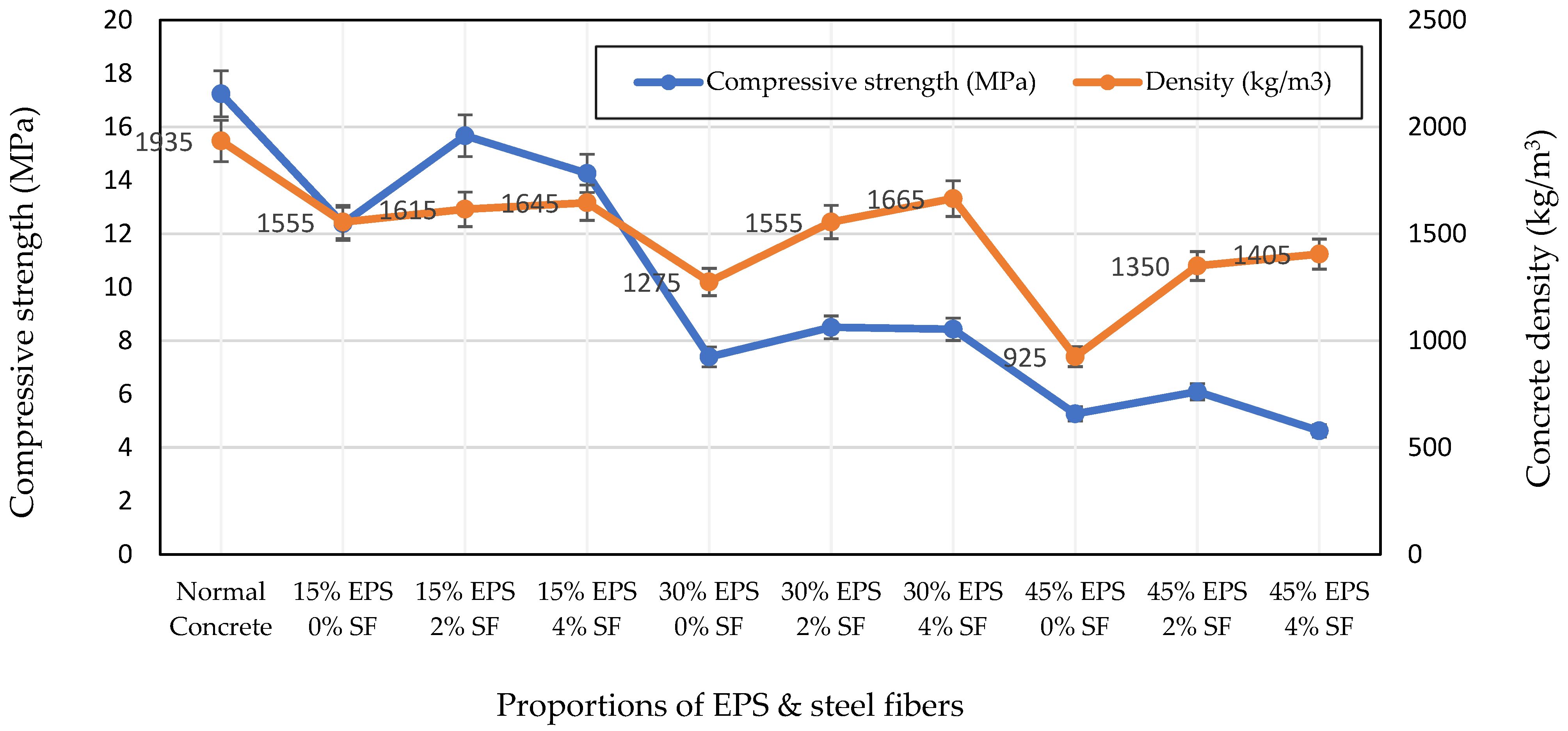

Lightweight concrete (LWC) has gained more interest and is increasingly being explored by researchers due to its low density in contrast to conventional concrete. Interest in LWC has increased as an alternative solution to normal concrete due to its low dead load and self-weight of structural elements. As a result, smaller sections can be achieved. According to a study, the compressive strength and bulk density of low-strength but lightweight concrete ranges from 7 to 18 MPa and 800 to 1400 kg/m

3, respectively [

1]. In past decades, researchers have tried to use different alternative materials as substitutes for aggregates to prepare LWC that can achieve acceptable strength with lower self-weight [

2,

3]. Initially, aggregates made from expanded fly ash, clays, preprocessed shales, and those that come from natural porous volcanic sources were used to lower the density of LWC [

4]. In the beginning, lightweight concrete was mainly used as an insulating material with air-entrained mixes of volcanic ash and hydrated lime to lessen the overall weight of the material [

5]. These low-density artificial lightweight aggregates have been used in concrete with varying degrees of success in density reduction. In recent years, expanded polystyrene (EPS) has been used as an alternative material to aggregates. The concrete industry has paid more attention to EPS due to its adequate low density, relative strength, and good thermal resistance. Expanded polystyrene is a lightweight cellular plastic with small spherical particles of 98% air and a wide range of densities (10 to 20 kg/m

3). The properties it possesses include having a closed-cell nature, being lighter weight and nonporous, and hydrophobicity [

6]. The utilization of EPS aggregate in concrete is mainly to reduce its overall weight in comparison to conventional concrete, which has a large self-weight with a low strength-to-weight ratio and substandard performance of thermal insulation [

7]. The keen innovation in the advancement of EPS-based concrete was the preparation under air-entrained conditions using lightweight aggregates (LWAs) of polymeric particles having bulk densities of about 16 to 160 kg/m

3. From the experimental work, it was observed that EPS beads of smaller sizes yielded concrete having a reasonable strength in the absence of additives [

2]. In addition, 30% EPS incorporation by volume of self-compacted concrete could reduce the density and compressive strength up to 30% and 40%, respectively [

8]. Similarly, in another study, the utilization of EPS in concrete mix was examined. It was reported that with the addition of EPS in concrete without a superplasticizer, the density decreased by about 11.3% and 16.2% vice versa [

9]. It was also reported that 5% EPS substitution as fine aggregate in concrete resulted in 16% lower compressive strength in comparison to control specimen strength. However, by increasing the EPS content up to 10%, the tensile strength was enhanced by 43% [

10]. Other research also demonstrated EPS’s effectiveness in enhancing concrete’s durability and mechanical properties [

11]. So, EPS is a discarded waste product like other various types of waste, and it has superior physical and mechanical capabilities that can be incorporated in concrete mix at optimal levels without compromising the strength of concrete in order to meet the demands for modern buildings and construction [

12,

13,

14].

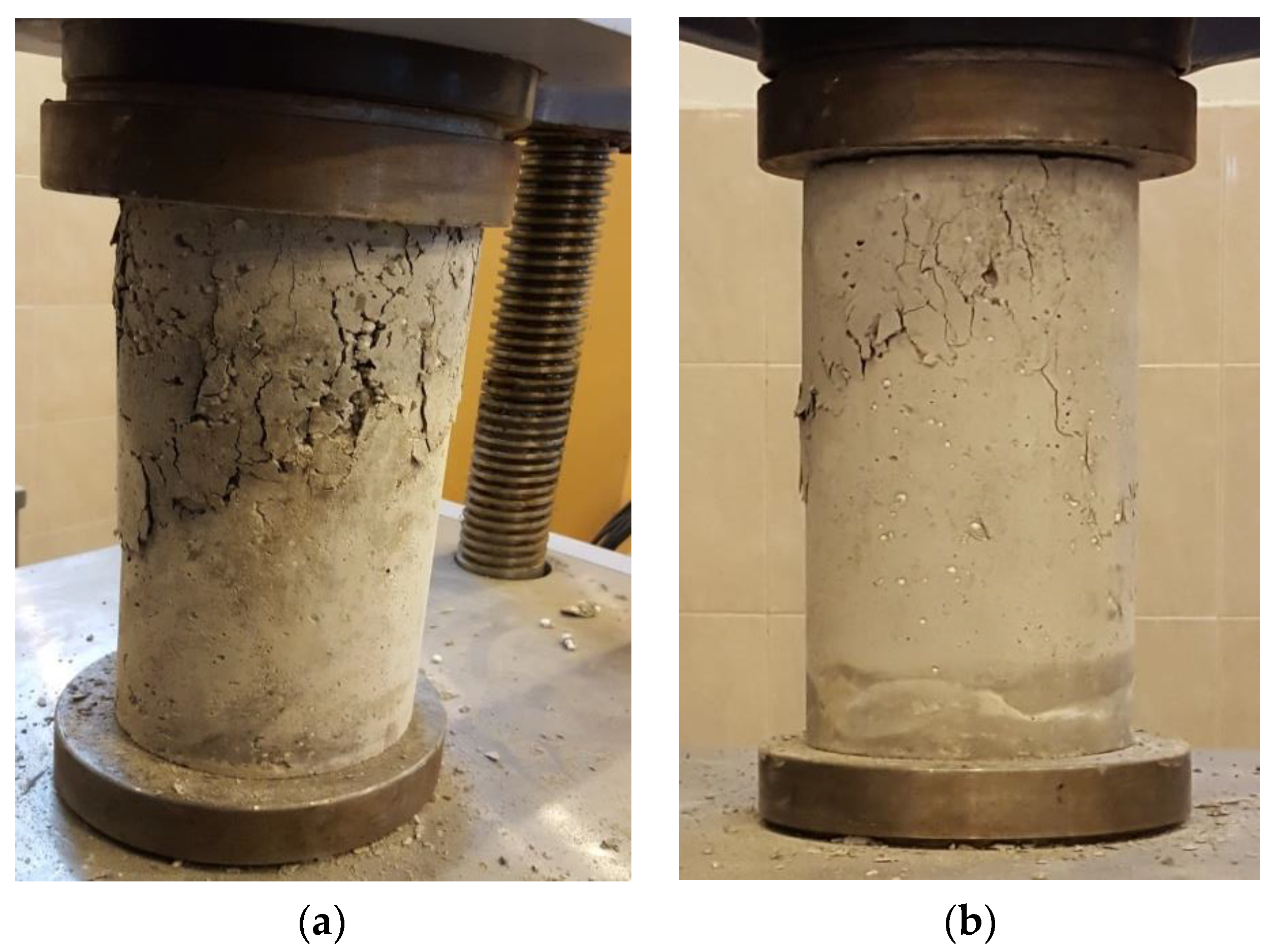

In addition, like other cementing agent materials, LWC has also brittle characteristics [

15]. This became clear when diagonal tension or shear failure was prominent in LWC. The brittleness of such lightweight concrete mix must be reduced with acceptable physical and mechanical properties [

16]. To achieve a ductile nature in materials, numerous studies have demonstrated the use of discrete fibers as reinforcement materials in concrete with reasonable performance [

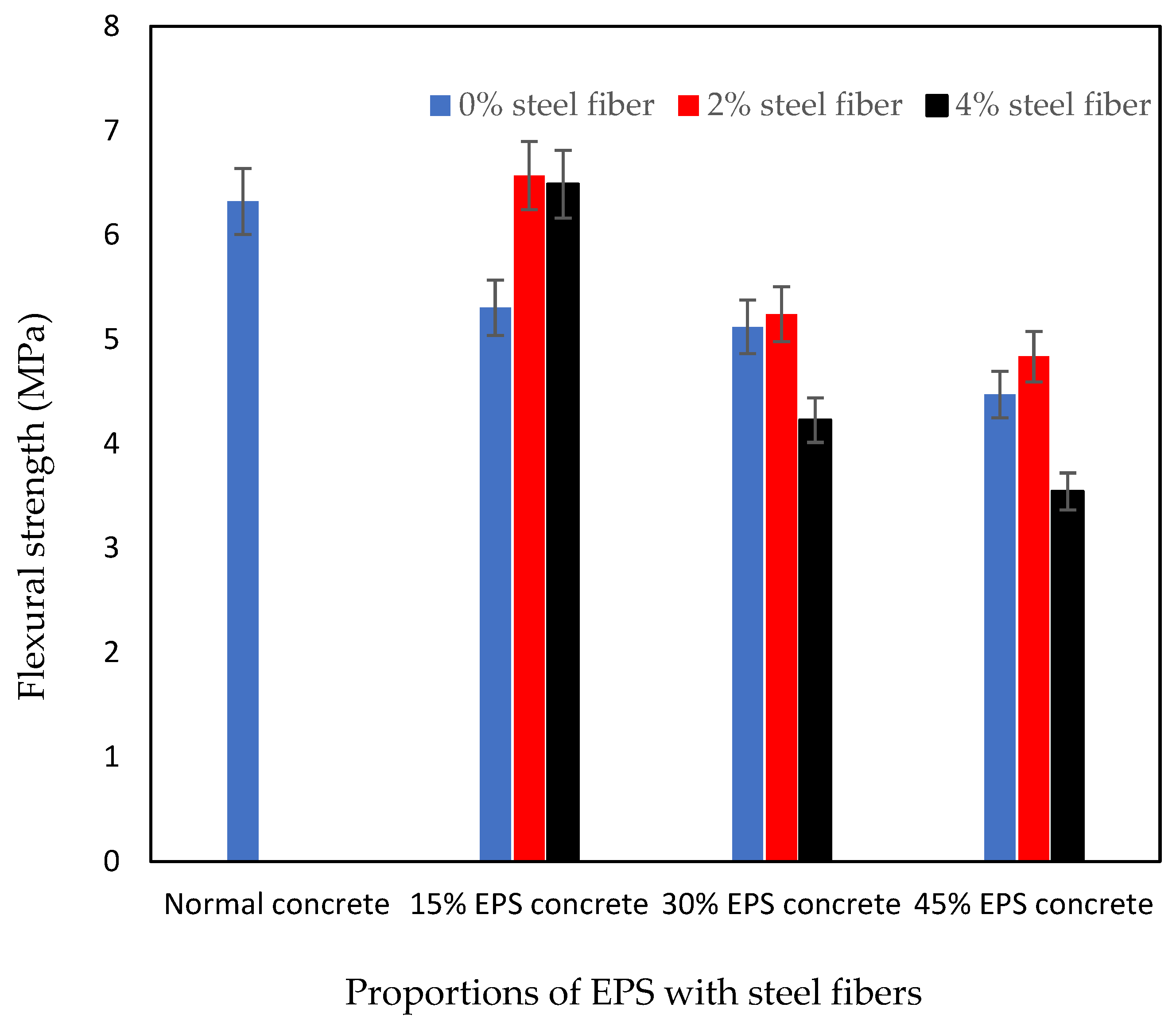

17]. Similarly, when fibers of a hooked-end nature were incorporated in concrete with varying contents of 0.0% to 1.5%, it resulted in a split tensile strength of 10% to 18% higher [

8]. At 2.0 vol% steel fiber, the compressive strength increased up to 20% [

18]. Material fatigue strength also increases with the introduction of steel fibers by reducing crack opening [

19]. Moreover, the steel fibers create a network structure in the concrete matrix, which effectively prevents segregation and cracks due to plastic shrinkage [

20].

Furthermore, adding supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) alters the inner structure of lightweight concrete, increasing the concrete mix’s brittleness and resistance against cracking [

21]. Recent research studies have proven that silica fume can effectively limit the inner concrete matrix by its bridging action. It reported increased strength development by adding about 10% condensed silica fume [

11]. It was observed that the substitution of silica fume and pozzolans up to 5% and 15% by weight of cement, respectively, showed increases in the compressive strength. The minute particles of SCMs work as microstructural modifiers, reducing the void spaces in the cement matrix. Similarly, silica fume works as an effective pozzolan, chemically reacting to produce calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) and increasing the mechanical properties of concrete mix as a result.

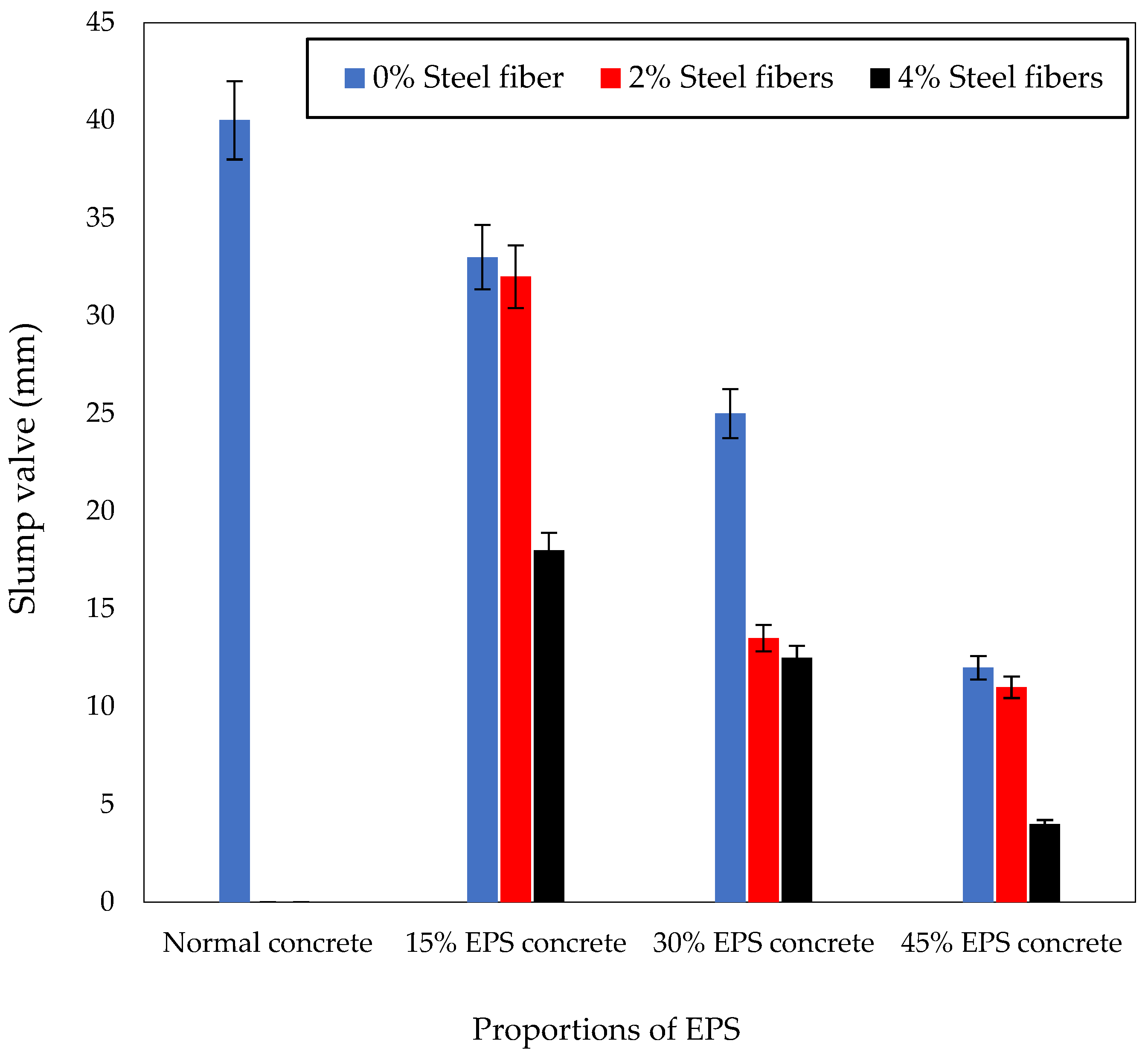

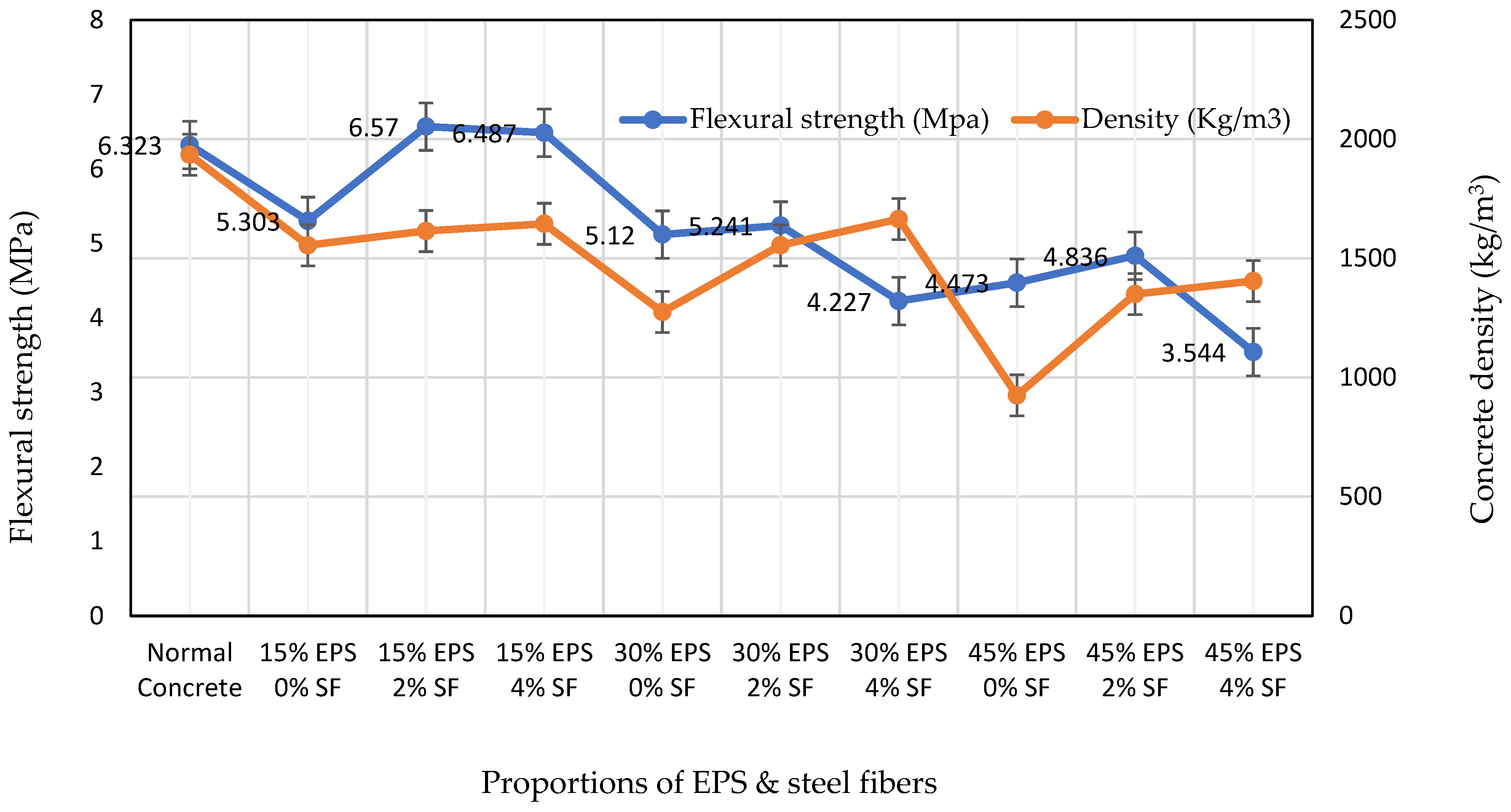

This study explores lightweight EPS as a substitute for coarse aggregate in low-density, low-strength, but lightweight concrete. However, freshly mixed EPS-based concrete faces challenges like segregation due to its lightweight and hydrophobic nature, impacting its workability. Optimal aggregate replacement levels affect concrete strength, and excessive substitution weakens it. Investigating EPS as a substitute is promising, but ongoing research mainly focuses on reducing density and imposing strength reduction challenges. Our study assesses the structural performance of lightweight concrete properties with varying EPS levels (0%, 15%, 30%, and 45%), steel fibers, and silica fume, aiming to address segregation and enhance bonding. The findings highlight that EPS-based concrete with steel fibers and silica fume shows potential with low density and higher flexural strength, and an optimal lightweight concrete design mix is proposed.