1. Introduction

Minimally invasive spine surgery (MISS) has become a standard approach in modern neurosurgery. Common MISS modalities for spine tumor resection include tubular retractors and mini-open retractors [

1,

2]. These systems are well-established in the context of degenerative spine diseases [

3,

4], spine infection, and tumor resection. However, in the context of endoscopic spine surgery, specifically Unilateral Biportal Endoscopy (UBE), there are few articles that describe how to perform different procedures with this technique [

5].

In this article, we describe the UBE surgical technique in the context of spine tumors, specifically extramedullary lesions such as meningiomas and schwannomas. We detail these procedures through our case series, providing a step-by-step description to demonstrate the advantages of UBE regarding safety, operative time, length of hospital stay, operative blood loss, complications, and functional outcomes.

2. Patient and Methods

A retrospective review was conducted on 11 consecutive cases of spinal lower thoracic and lumbar spinal extramedullary tumors operated by a senior surgeon experienced in the UBE technique. All surgeries were performed at San Jose Celaya Hospital between January 2023 and May 2025. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Hospital San Jose Celaya (Protocol code: 000123-2024).

Inclusion criteria comprised patients with a diagnosis of a spinal extramedullary tumor (intradural or extradural extension) involving three vertebral levels or less within the thoracic and lumbar regions; lesion size was not considered an exclusion criterion.

Procedures were performed using a high-definition monitor, standard hook probes, micro-forceps, small curettes, narrow osteotomes, and modified bipolar electrocautery probes. The setup also utilized standard arthroscopy equipment, including an arthroscopic shaver (functioning as both bone drill and burr) and radiofrequency (RF) coagulator wands for hemostasis and soft-tissue debridement. A 30° endoscope with a diameter of 4 mm and length of 175 mm, inserted into a 6-mm saline infusion sleeve, was employed, as this configuration is typically sufficient for basic UBE procedures [

6,

7,

8].

Data was collected from hospital medical records and intraoperative video recordings. Preoperative analysis relied principally on clinical evaluation and spinal Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). Parameters analyzed included surgical technique, operative time, operative blood loss, tumor histopathology, hospital stay, and complications.

The extent of resection was assessed perioperatively and confirmed with postoperative MRI. Patient outcomes were evaluated in the immediate postoperative period and at 6 months follow-up using the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) and the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for back and leg pain.

2.1. Surgical Technique

Surgical planning involved the UBE technique via two small incisions. A right-sided approach was utilized in 8 cases and a left-sided approach in 3 cases. Localization was achieved using fluoroscopic landmarks: the mid-pedicular lines for the right-sided approach and infra-pedicular lines in the horizontal plane for the left-sided approach, along with the medial pedicular line in the vertical plane. We recommend obtaining Anteroposterior and lateral images to confirm location; this ensures optimal tissue mobility and flexibility at the time of durotomy and tumor dissection. While a midline durotomy is generally recommended, this can be modified depending on the location of the lesion. The patient was positioned prone on a radiolucent operating table. The operating room was set up in the standard fashion for biportal endoscopic surgery (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

Step 1—The incision was marked as previously described. In all cases, the incision was performed with a #20 scalpel blade oriented at 90° to the fluoroscopic landmarks. We performed this same incision in the fascia and angled the scalpel in a cephalocaudal direction to open the muscular tissue and facilitated the creation of the working space for continuous water flow without increasing pressure in the surgical chamber [

9].

Step 2—The 30° biportal endoscope (or standard 30° arthroscope) and working instruments were introduced directly, without the use of serial dilators. This saved time and preserved tissue integrity by minimizing disruption during the creation of the working space.

Step 3—Continuous saline irrigation was maintained using gravity (70–100 cm height) or a pump system (20–30 mmHg) at room temperature. Minimal tissue dissection was performed with disc forceps. Subsequently, the working space was enlarged using plasma RF as necessary. A flavectomy was performed using an over-the-top technique, extending the laminotomy bilaterally to the cephalic and caudal lamina while preserving anatomical structures. We aimed to achieve a wider “O-cut” decompression as necessary and proceeded when all neural structures could be visualized free of ligamentum flavum [

10].

Step 4—With the exposure of the thecal sac, a vertical midline durotomy of 2.0 to 2.5 cm was performed, adjusted to the size of the lesion. We recommended a maximum 3 cm incision to facilitate manipulation of the dura for larger lesions (this step was critical for the chosen closure technique).

Step 5—Following dural opening, water flow was strictly controlled between 15 and 20 mmHg (pump) or by lowering saline bags to 50–60 cm (gravity). This achieved a constant minimal flow sufficient for dissection without displacing nerves from the dural sac margin. Tumor resection was performed using conventional microsurgical techniques, such as fragmentation or en-bloc Gross Total Resection (GTR). This was feasible in UBE because standard instruments such as Rhoton or Penfield dissectors, curettes, and pituitary forceps were utilized.

A distinct advantage of UBE was “intermittent hydrostatic dissection”. This involved temporarily increasing the pump flow from 15 mmHg to 30 mmHg to dissect adhesions. However, we recommend using this technique for a maximum of 1 min to avoid complications associated with high pressure, such as elevation of intra-cranial pressure. For hemostasis within the canal, only specific UBE plasma electrodes were used. The resection involved a combination of dissection and traction with Rhoton dissectors, nucleus pulposus forceps, and pituitary forceps to ensure safety. Once resection was complete, the hemostasis was strictly verified. With a 30° UBE endoscope, it was possible to obtain a panoramic “scanning effect” that improved all visual fields [

11,

12,

13].

Step 6—After resection, dural closure was a challenge. We performed a continuous simple suture with extracorporeal double knots. Hemoclips were another safe option for dural closure in short durotomies (<1 cm), with or without a synthetic dural patch. We reserved the synthetic patch primarily for cases of asymmetrical dural opening [

14].

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were utilized to summarize patient demographics, tumor characteristics, surgical parameters, and clinical outcomes, stratified by histopathological diagnosis. Continuous variables (e.g., age, operative time, estimated operative blood loss, and hospital length of stay) were reported as means and standard deviations (SD). Categorical variables (e.g., gender, tumor location, extent of resection, and symptom presentation) were summarized as frequencies and percentages.

2.3. Inferential Statistics

Due to the limited sample size within each tumor subgroup, exact non-parametric statistical methods were prioritized for comparative analyses. The primary outcome measure was the change in leg VAS scores from preoperative baseline to 6-month postoperative follow-up.

For within-group comparisons of preoperative versus postoperative leg VAS scores, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (exact p-values) was performed with a one-tailed greater alternative hypothesis to assess improvement. For subgroups with extremely small samples (n = 2), exact probabilities were derived directly. The Sign Test was employed as a complementary non-parametric approach to assess the proportion of patients showing improvement.

A clinically meaningful improvement was defined as a reduction of ≥2 points on the 10-point VAS scale, consistent with established Minimal Clinically Important Difference (MCID) thresholds for spine pain assessment. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using Python (version 3.9) with the SciPy library (version 1.7.3).

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics and Tumor Characteristics

Between January 2023 and May 2025, eleven patients underwent UBE resection of lower thoracic and lumbar spinal extramedullary tumors at our institution. The cohort comprised 7 women (63.6%) and 4 men (36.4%) with a mean age of 59.3 ± 18.2 years (range: 12–76 years); one pediatric patient (12 years old) was included in the series.

Histopathological distribution revealed 5 meningiomas (45.5%), 4 schwannomas (36.4%), and 2 dermoid cysts (18.2%). All lesions were located within the lower thoracic and lumbar spine between levels T10 and L4. Regarding clinical presentation, radicular leg pain was the predominant symptom in 7 patients (63.6%), while 5 patients (45.5%) presented primarily with axial back pain. All patients demonstrated neurological deficits, including motor weakness, sensory alterations, or both. The mean duration of symptoms prior to surgical intervention was 4 months (

Table 1).

3.2. Surgical Outcomes and Complications

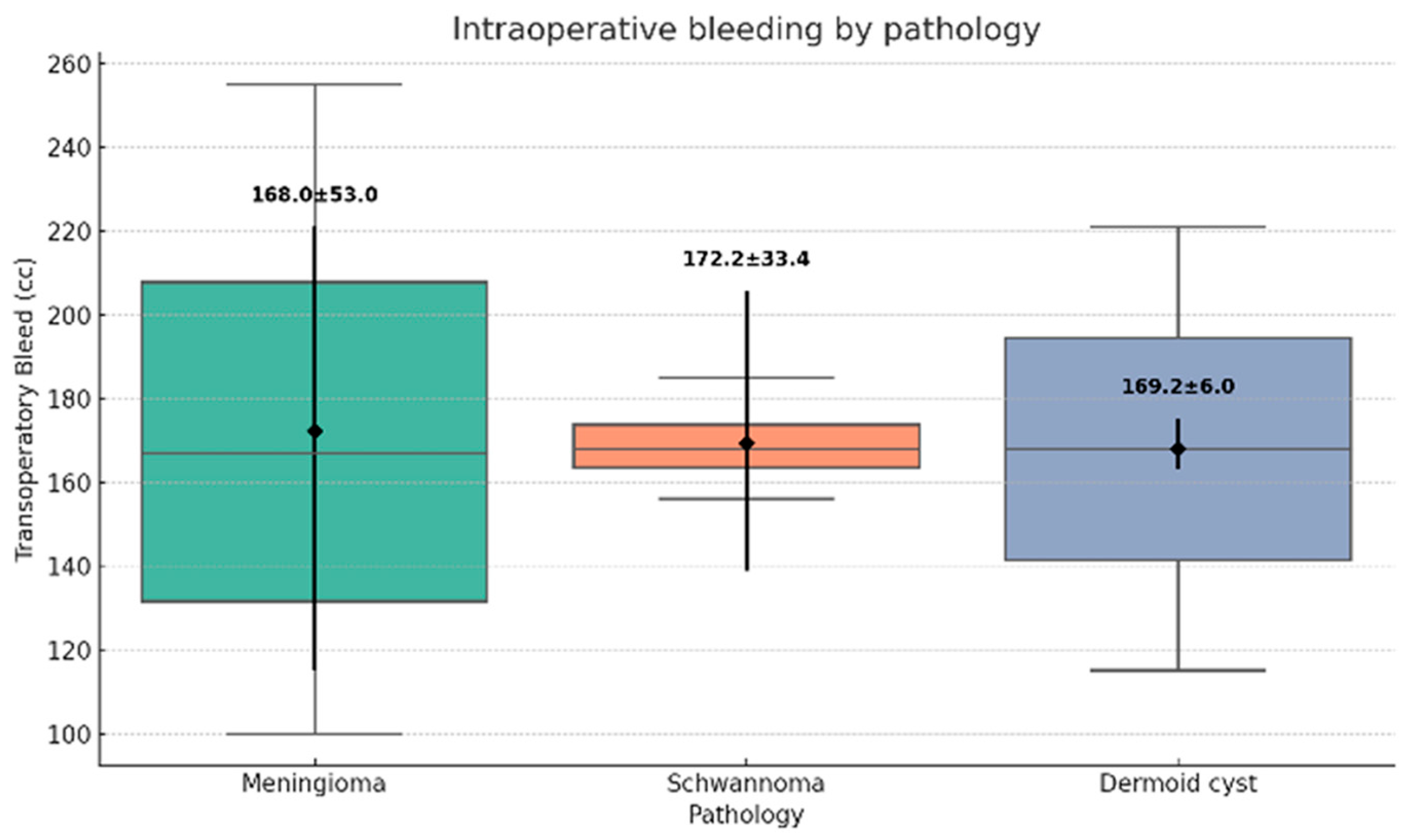

All surgical procedures were successfully completed via the UBE technique, with no conversions to open surgery. The mean operative time was 168.5 ± 24.3 min (range: 100–200 min) (

Figure 4). Estimated operative blood loss averaged 48.1 ± 12.7 mL (range: 30–70 mL) (

Figure 5).

The Simpson scale grades I and II were achieved in 9 cases (81.8%). Subtotal resection was performed in two patients with meningiomas due to dense dural adhesions; in these instances, RF ablation was applied to residual tumor adherent to the dural surface. No intraoperative complications were recorded. All patients were mobilized within 12 h postoperatively.

The mean hospital length of stay was 1.5 ± 0.7 days (range: 1–3 days). Postoperatively, one patient (9.1%) developed a contained cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak, which resolved spontaneously within 3 months without requiring revision surgery.

3.3. Pain and Functional Outcomes

Complete data for preoperative and postoperative leg VAS scores were available for 7 patients (63.6%). The remaining 4 patients presented primarily with axial back pain or lacked complete VAS documentation. The analysis was stratified by histopathology: meningiomas (n = 2), schwannomas (n = 3), and dermoid cysts (n = 2).

In the meningioma subgroup, preoperative leg VAS decreased from a mean of 8.5 ± 0.7 to 2.5 ± 0.7 at 6-month follow-up (mean improvement: 6.0 ± 1.4 points). While statistical significance was not reached due to sample size, clinical improvement was substantial, with all patients exceeding the MCID threshold.

The schwannoma group demonstrated a mean reduction in leg VAS from 7.7 ± 1.2 to 1.7 ± 1.2 postoperatively (mean improvement: 6.0 ± 2.0 points). Although the Wilcoxon signed-rank test yielded a p-value of 0.125, the Sign Test indicated that 100% of patients (3/3) experienced clinically significant improvement.

Patients with dermoid cysts also showed consistent improvement, with mean leg VAS scores decreasing from 7.5 ± 0.7 preoperatively to 2.0 ± 0.0 at follow-up (mean improvement: 5.5 ± 0.7 points).

3.4. Overall Pain Outcomes

Overall, all 7 patients presenting with radicular symptoms demonstrated improvement in leg pain scores, achieving a mean reduction of 5.8 ± 1.6 points on the VAS scale; importantly, no patient reported worsening of symptoms at the 6-month follow-up.

Regarding axial symptoms, back VAS scores were analyzed for the 4 patients presenting with predominant back pain. The mean preoperative back VAS improved from 8.3 ± 1.0 points to 1.5 ± 0.6 points postoperatively (mean improvement: 6.8 ± 1.5 points).

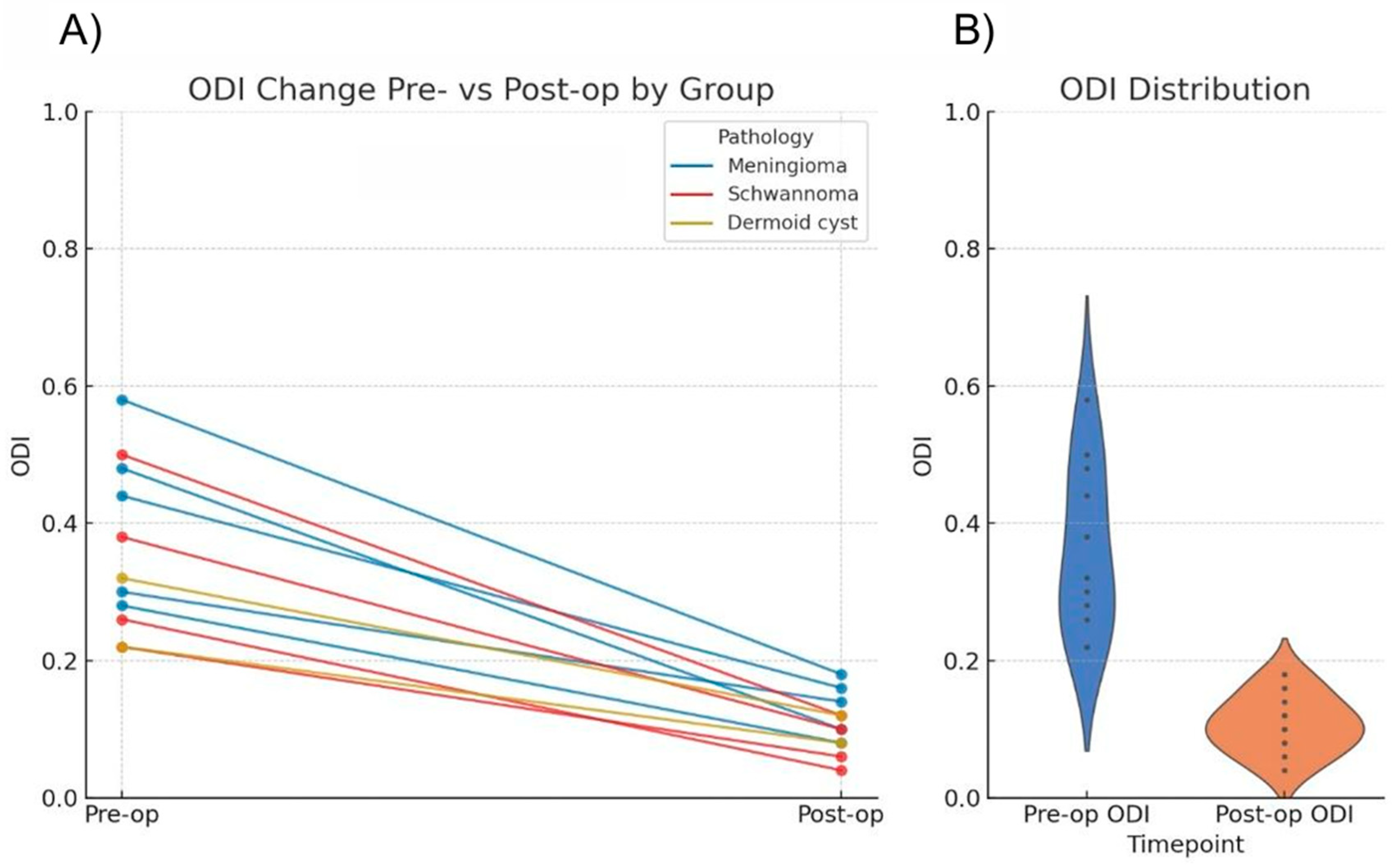

Functional outcomes were assessed using ODI scores. Preoperatively, all patients exhibited moderate to severe disability (score range: 21–60%). At the 6-month follow-up, the majority of the cohort achieved minimal disability status (0–20%) (

Table 2).

Statistical analysis using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test confirmed a significant reduction in ODI scores (

p = 0.00098) (

Table 2 and

Figure 6).

Regarding neurological status, all patients demonstrated improvement in motor and sensory deficits. No new permanent neurological deficits were recorded. One patient in the schwannoma group experienced transient postoperative paresthesia in the corresponding dermatome, which resolved spontaneously within 3 months.

3.5. Illustrative Case

Schwannoma

We present the case of a 58-year-old female presenting with a 2-month history of progressive left leg radiculopathy (Leg VAS 9/10), low back pain (Back VAS 7/10), and weakness in both lower limbs resulting in an inability to ambulate, along with neurogenic bladder. MRI revealed an L2–L3 intradural extramedullary lesion occupying 80% of the spinal canal (

Figure 1).

Surgical intervention was performed using the UBE technique via a right-sided approach based on spinometric landmarks (

Figure 2), with minimal muscular tissue disruption. Bilateral laminotomy of the cephalic and caudal laminae was completed with a wider “O-cut” using the over-the-top technique, followed by flavectomy using Kerrison rongeurs and curettes. A midline durotomy was performed with a #11 scalpel blade, and the incision was extended with a Rhoton dissector. Following visualization of the tumor, dissection was performed with Rhoton and Penfield dissectors. Hydrostatic dissection was facilitated by temporarily increasing the pump flow, after which the lesion was extracted with pituitary forceps without complications. Dural closure was achieved with a 6-0 prolene suture using the previously described technique (

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrates that UBE is a safe and effective technique for the resection of thoracolumbar intradural extramedullary (IDEM) tumors, achieving a Simpson scale grades I and II rate of 81.8% with minimal perioperative morbidity. Our findings suggest that UBE combines the visualization advantages of endoscopic surgery with the manipulative freedom of open microsurgery, overcoming some of the limitations inherent to fixed tubular retractor systems [

1].

Historically, the gold standard for IDEM tumor resection has been open laminectomy. While effective, this approach involves extensive subperiosteal muscle stripping, which is associated with postoperative spinal instability, muscle atrophy, and chronic back pain [

3]. Minimally invasive tubular approaches attempted to address these issues but are often limited by a restricted tunnel vision and a fixed trajectory that complicates the removal of large or ventrally located lesions [

2]. Unlike tubular systems, UBE creates a ‘scanning effect’ via independent optical and working portals, allowing multi-angled visualization of the tumor–dural interface without expanding the bony corridor [

15].

From a technical standpoint, fluid management is the cornerstone of safe intradural endoscopy. A key technical nuance observed in our series is the utility of intermittent water dissection. By temporarily increasing irrigation pressure (from 15 to 30 mmHg), we utilized the hydrostatic force to gently separate the arachnoid plane from the tumor capsule, minimizing traction on neural elements. However, we strictly emphasize returning to low pressure immediately after dissection to prevent intracranial hypertension or dural detachments, a protocol that likely contributed to our safety profile [

16].

Regarding clinical outcomes, our cohort showed a statistically significant improvement in disability scores (ODI,

p = 0.00098). Although the reduction in leg pain (VAS) did not reach statistical significance in all subgroups due to the small sample size, a common limitation in pilot case series, the clinical magnitude of relief was substantial. All patients exceeded the MCID threshold of 2 points, which arguably holds greater relevance for patient quality of life than statistical probability in small cohorts [

17].

However, the technique is not devoid of challenges. We observed one case (9.1%) of a contained CSF leak. Although this aligns with reported rates in IDEM tumor surgery, which range from 6.6% to 16% in large series [

18,

19], it highlights the difficulty of water-tight dural closure in a fluid environment. Therefore, we advocate for a hybrid closure technique using continuous sutures reinforced with clips or patches when necessary. Furthermore, given the steep learning curve associated with endoscopic depth perception, we strongly recommend that surgeons surpass a learning curve of at least 50 to 100 degenerative UBE cases before attempting intradural oncological resection [

20].

5. Conclusions

This study presents a case series of 11 lower thoracic and lumbar spinal extramedullary tumors managed via the UBE technique, providing a detailed step-by-step surgical description. Traditionally, these lesions were treated using approaches associated with extensive muscle disruption and alteration of spinal biomechanics, often resulting in instability or chronic low back pain. Our results demonstrate that the UBE technique significantly improves patient outcomes while utilizing minimal 1-cm incisions.

Statistically significant improvements were observed in functional outcomes, as evidenced by the reduction in ODI scores (p = 0.00098). Regarding oncological efficacy, we achieved Simpson scale grades I and II rates comparable to those reported for open and tubular surgeries.

However, to ensure patient safety, we strongly recommend a minimum surgical experience of 50 to 100 degenerative cases before performing UBE tumor resection. The UBE technique is a rapidly evolving field. We anticipate that it will become a standard of care for spinal tumor resection soon, further expanding the frontier of unilateral biportal endoscopy in spine surgery.