Endoscopic Management of an Inflammatory Lesion Suspected of Being a Brown Tumor of the Frontal Process of the Maxilla—Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

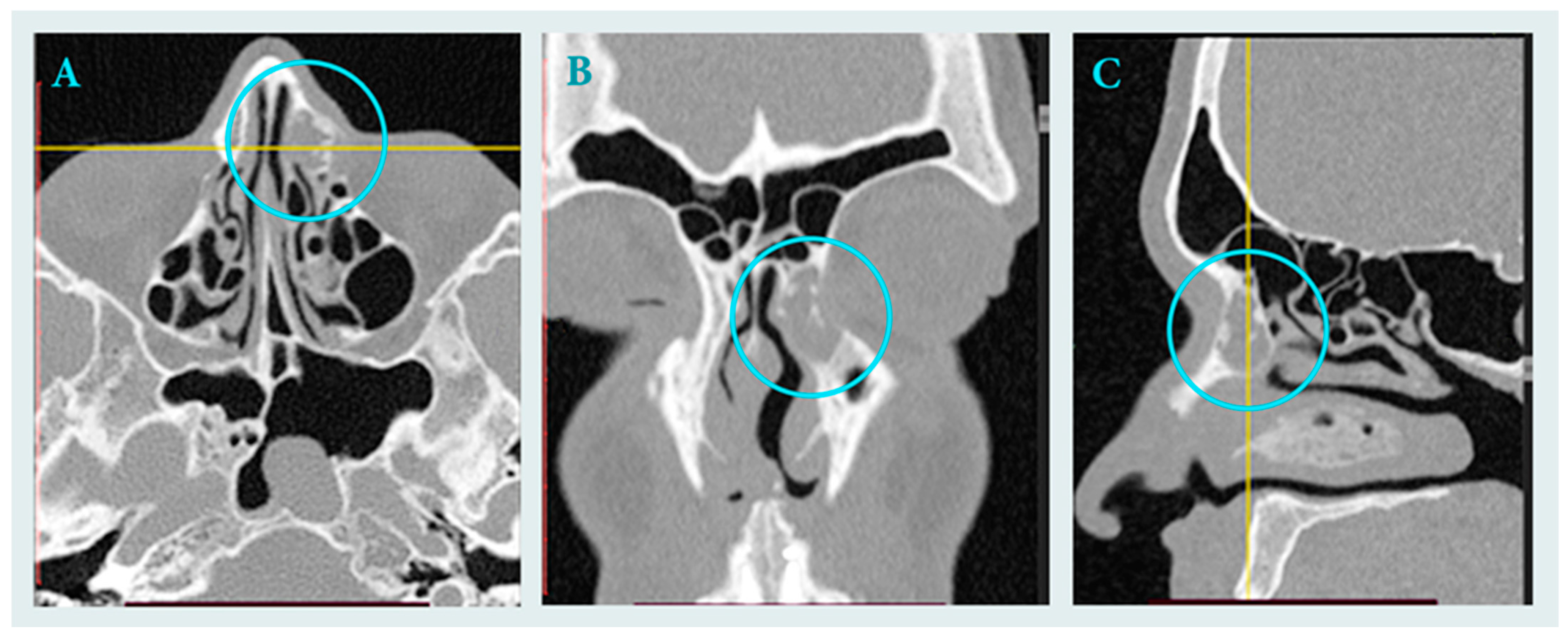

2. Case Report

2.1. Clinical Data

2.2. Surgical Treatment

2.3. Histopathology

2.4. Follow up

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| CBCT | Cone Beam Computed Tomography |

| PTH | Parathyroid hormone |

| ALP | Alkaline phosphatase |

References

- Fokkens, W.J.; Lund, V.J.; Hopkins, C.; Hellings, P.W.; Kern, R.; Reitsma, S.; Toppila-Salmi, S.; Bernal-Sprekelsen, M.; Mullol, J.; Alobid, I.; et al. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2020. Rhinology 2020, 58 (Suppl. S29), 1–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Psillas, G.; Papaioannou, D.; Petsali, S.; Dimas, G.G.; Constantinidis, J. Odontogenic maxillary sinusitis: A comprehensive review. J. Dent. Sci. 2021, 16, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gontarz, M.; Wyszyńska-Pawelec, G.; Zapała, J.; Gałązka, K.; Tomaszewska, R.; Lazar, A. IgG4-related disease in the head and neck region: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Pol. J. Pathol. 2016, 67, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Chen, F.; Zhang, W.; Sun, H.; Yan, F.; Pan, Y.; Zhu, D.; Yang, Q.; et al. Expert consensus on odontogenic maxillary sinusitis multi-disciplinary treatment. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2024, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lis, E.; Gontarz, M.; Marecik, T.; Wyszyńska-Pawelec, G.; Bargiel, J. Residual cyst mimicking an aggressive neoplasm—A life-threatening condition. Oral 2024, 4, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedhila, M.; Belkacem Chebil, R.; Marmouch, H.; Terchalla, S.; Ayachi, S.; Oueslati, Y.; Oualha, L.; Douki, N.; Khochtali, H. Brown tumors of the jaws: A retrospective study. Clin. Med. Insights Endocrinol. Diabetes 2023, 16, 11795514231210143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelke, K.; Łuczak, K.; Janeczek, M.; Plichta, M.; Małyszek, A.; Tarnowska, M.; Kuropka, P.; Dobrzyński, M. The occurrence of mandible brown tumor mimicking central giant cell granuloma in a case suspicious of primary hyperparathyroidism—Troublesome diagnostic dilemmas. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimarães, L.M.; Valeriano, A.T.; Rebelo Pontes, H.A.; Gomez, R.S.; Gomes, C.C. Manifestations of hyperparathyroidism in the jaws: Concepts, mechanisms, and clinical aspects. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2022, 133, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bignami, M.; Volpi, L.; Karligkiotis, A.; De Bernardi, F.; Pistochini, A.; AlQahtani, A.; Meloni, F.; Verillaud, B.; Herman, P.; Castelnuovo, P. Endoscopic endonasal resection of respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartomas of the sinonasal tract. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014, 4, 961–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantino, G.d.T.; Sasaki, F.; Tavares, R.A.; Voegels, R.L.; Butugan, O. Inflammatory pseudotumors of the paranasal sinuses. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2008, 74, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Niu, X.; Zhang, K.; He, T.; Sun, Y. Potential Otogenic Complications Caused by Cholesteatoma of the Contralateral Ear in Patients with Otogenic Abscess Secondary to Middle Ear Cholesteatoma of One Ear: A Case Report. World J. Clin. Cases 2022, 10, 10220–10227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Wu, X.; Xia, Q.; Xie, Z.; Xiao, H.; Sun, Y.; Jia, Y.; Yao, D.; Guang, X.; Cheng, H. Diffuse-Type Tenosynovial Giant Cell Tumor Invading the Temporal Bone: Three Cases. Ear Nose Throat J. 2025, 104, NP450–NP455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasindran, V.; Ravikumar, A.; Senthil, K.; Somu, L. Inflammatory pseudotumours of the paranasal sinuses. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2007, 59, 267–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiliti, B.A.; Martin, R.M.; Santos-Silva, A.R.; Matuck, B.F.; Machado, G.G.; Rocha, A.C. Brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism in the maxillofacial region: A retrospective study with 19 patients. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2025; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Head and Neck Tumours, 5th ed.; WHO Classification of Tumours Series; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2022; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Morawska-Kochman, M.; Jermakow, K.; Nelke, K.; Zub, K.; Pawlak, W.; Dudek, K.; Bochnia, M. The pH value as a factor modifying bacterial colonization of sinonasal mucosa in healthy persons. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2019, 128, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morawska-Kochman, M.; Marycz, K.; Jermakow, K.; Nelke, K.; Pawlak, W.; Bochnia, M. The presence of bacterial microcolonies on the maxillary sinus ciliary epithelium in healthy young individuals. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brook, I. Microbiology of sinusitis. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2011, 8, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelke, K.; Diakowska, D.; Morawska-Kochman, M.; Janeczek, M.; Pasicka, E.; Łukaszewski, M.; Żak, K.; Nienartowicz, J.; Dobrzyński, M. The CBCT retrospective study on Underwood septa and their related factors in maxillary sinuses—A proposal of classification. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasemsiri, P.; Prevedello, D.M.; Otto, B.A.; Old, M.; Ditzel Filho, L.; Kassam, A.B.; Carrau, R.L. Endoscopic endonasal technique: Treatment of paranasal and anterior skull base malignancies. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2013, 79, 760–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marecik, T.; Gontarz, M.; Gąsiorowski, K.; Bargiel, J.; Wyszyńska-Pawelec, G. Endoscopic Management of an Inflammatory Lesion Suspected of Being a Brown Tumor of the Frontal Process of the Maxilla—Case Report. Surgeries 2025, 6, 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/surgeries6040107

Marecik T, Gontarz M, Gąsiorowski K, Bargiel J, Wyszyńska-Pawelec G. Endoscopic Management of an Inflammatory Lesion Suspected of Being a Brown Tumor of the Frontal Process of the Maxilla—Case Report. Surgeries. 2025; 6(4):107. https://doi.org/10.3390/surgeries6040107

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarecik, Tomasz, Michał Gontarz, Krzysztof Gąsiorowski, Jakub Bargiel, and Grażyna Wyszyńska-Pawelec. 2025. "Endoscopic Management of an Inflammatory Lesion Suspected of Being a Brown Tumor of the Frontal Process of the Maxilla—Case Report" Surgeries 6, no. 4: 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/surgeries6040107

APA StyleMarecik, T., Gontarz, M., Gąsiorowski, K., Bargiel, J., & Wyszyńska-Pawelec, G. (2025). Endoscopic Management of an Inflammatory Lesion Suspected of Being a Brown Tumor of the Frontal Process of the Maxilla—Case Report. Surgeries, 6(4), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/surgeries6040107