Foreign Body Presenting as Golden Hypopyon

Abstract

1. Introduction

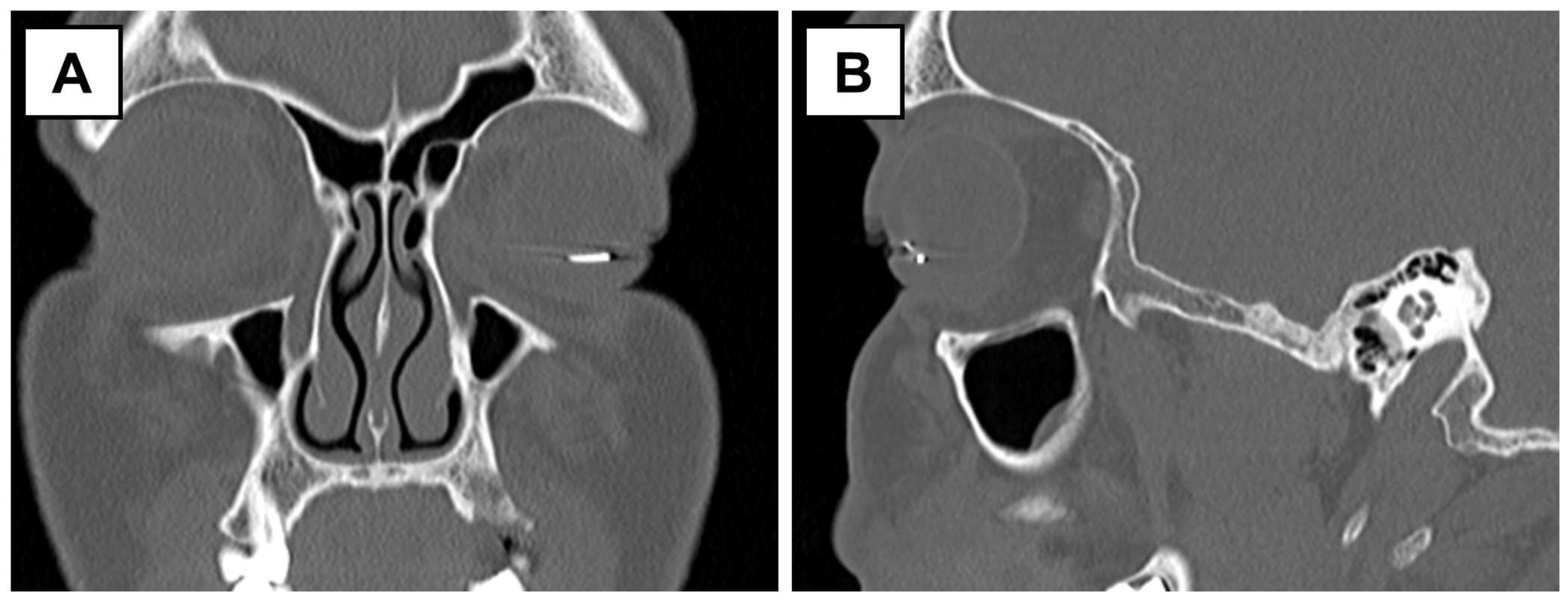

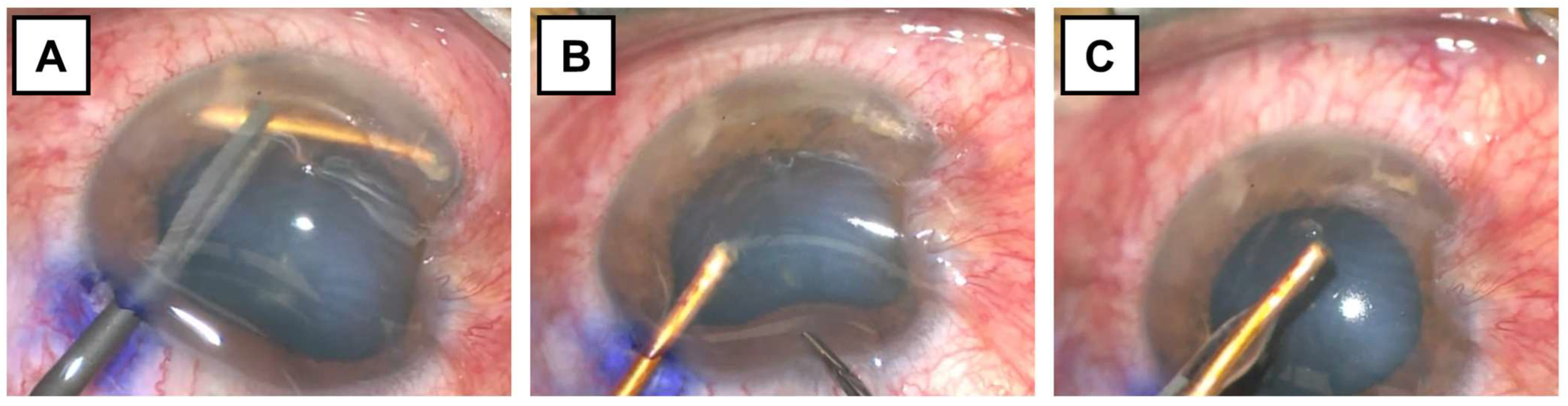

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IOFB | Intraocular foreign body |

| RAPD | Relative afferent pupillary defect |

| CF | Counting fingers |

References

- Widyanatha, M.I.; Sungkono, H.S.; Ihsan, G.; Virgana, R.; Iskandar, E.; Kartasasmita, A.S. Clinical findings and management of intraocular foreign bodies (IOFB) in third-world country eye hospital. BMC Ophthalmol. 2025, 25, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; DiSclafani, M.; Jeang, L.; Shah, A.A. Open Globe Injuries: Review of Evaluation, Management, and Surgical Pearls. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2022, 16, 2545–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ustaoglu, M.; Karapapak, M.; Tiryaki, S.; Dirim, A.B.; Olgun, A.; Duzgun, E.; Sendul, S.Y.; Ozcan, D.; Guven, D. Demographic characteristics and visual outcomes of open globe injuries in a tertiary hospital in Istanbul, Turkey. Eur. J. Trauma. Emerg. Surg. 2020, 46, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, L.; Kapadia, M.K.; Singh, R.P.; Sheridan, R.; Hatton, M.P. Gender differences in etiology and outcome of open globe injuries. J. Trauma. 2005, 59, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.C.; Lee, S.Y.; Yoon, C.K.; Park, U.C.; Heo, J.W.; Lee, E.K. Intraocular Foreign Body: Diagnostic Protocols and Treatment Strategies in Ocular Trauma Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong, A.J.; Fan, K.C.; Golshani, B.; Bobinski, M.; McGahan, J.P.; Eliott, D.; Morse, L.S.; Modjtahedi, B.S. Multimodal imaging features of intraocular foreign bodies. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2019, 34, 518–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohlhausen, M.; Menke, B.A.; Begley, J.; Kim, S.; Debiec, M.R.; Conrady, C.D.; Yeh, S.; Justin, G.A. Advances in the management of intraocular foreign bodies. Front. Ophthalmol. 2024, 4, 1422466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deramo, V.A.; Shah, G.K.; Baumal, C.R.; Fineman, M.S.; Correa, Z.M.; Benson, W.E.; Rapuano, C.J.; Cohen, E.J.; Augsburger, J.J. The role of ultrasound biomicroscopy in ocular trauma. Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 1998, 96, 355–365; discussion 365–367. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guha, S.; Bhende, M.; Baskaran, M.; Sharma, T. Role of ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) in the detection and localisation of anterior segment foreign bodies. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2006, 35, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, J.M. Modified No-Touch Technique for Removal of a Dexamethasone Implant that has Migrated to the Anterior Chamber. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2020, 28, 238–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alkhabaz, A.; Guo, L.Y.; DeBoer, C. Foreign Body Presenting as Golden Hypopyon. Surgeries 2025, 6, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/surgeries6030068

Alkhabaz A, Guo LY, DeBoer C. Foreign Body Presenting as Golden Hypopyon. Surgeries. 2025; 6(3):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/surgeries6030068

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlkhabaz, Anas, Lucie Y. Guo, and Charles DeBoer. 2025. "Foreign Body Presenting as Golden Hypopyon" Surgeries 6, no. 3: 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/surgeries6030068

APA StyleAlkhabaz, A., Guo, L. Y., & DeBoer, C. (2025). Foreign Body Presenting as Golden Hypopyon. Surgeries, 6(3), 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/surgeries6030068