Abstract

Background: Irreversible pulpitis is a severe inflammation of the dental pulp. The purpose of this clinical trial was to evaluate the effectiveness of an inferior alveolar nerve block (IANB) injection followed by oral dexamethasone administration in reducing the pain associated with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis (SIP) in mandibular molars, without performing conventional pulpotomy. Methods: A sample of 80 subjects suffering from acute pain due to SIP on a mandibular molar were assigned to the dexamethasone group, who received an IANB injection followed by one oral dose of 4 mg of dexamethasone during the emergency visit followed by one dose of 4 mg after 8 h, or the control group, who received a conventional pulpotomy. Both groups received complete endodontic treatment after five to six days. The intensity of the preoperative pain and pain levels were measured in both groups at different times after each intervention. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the pain scores between the groups at the same time point, while Friedman’s test was used to compare the pain scores between the four time points within the same intervention group, followed by the Bonferroni correction for multiple pairwise comparisons. Success was determined when the pain score on the visual analogue scale (VAS) was 20 or lower. Results: A survival analysis was conducted, where the event was considered as the disappearance of symptoms (or success: pain score ≤ 20). For both groups, the pain significantly decreased 8 h postoperatively (p < 0.05). The success rates at 8 and 12 h were significantly higher in the dexamethasone group compared to the control group (p = 0.05). However, the pain scores at 24 h remained comparable. Conclusions: An IANB injection followed by 8 mg of oral dexamethasone could reduce pain significantly in patients with SIP without performing conventional pulpotomy. The oral administration of dexamethasone could therefore be a valuable strategy to temporarily alleviate SIP symptoms until definitive treatment becomes feasible. Dexamethasone is a temporary pain management strategy rather than a replacement for pulpotomy.

1. Introduction

Irreversible pulpitis is a severe inflammation of the dental pulp [1], with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis (SIP)-related pain accounting for more than 45% of the reasons for urgent dental consultation [2]. Hence, partial pulpotomy [3] or full pulpotomy [4] has been recommended for the emergency treatment of irreversible pulpitis in multirooted teeth. SIP may constitute an unforeseen and significant workload that disturbs the ordinary workflow in a dental clinic. The literature reports challenges in achieving appropriate and deep anesthesia, especially when performing pulpotomy on mandibular molars [5,6], as the success rate of an inferior alveolar nerve block (IANB) decreases drastically in patients with SIP. Pulpal inflammation has often been cited as the primary cause of IANB failure in SIP: the patient experiences pain, and the dentist interrupts the treatment to perform additional injections, whether buccal, intraligamentary, or intrapulpal [7,8]. A specialized critical setup, adequate time, and the competence of the dental practitioner are all required when a patient presents with this condition. One of the main problems in handling such emergencies is that the patient shows up at the clinic without a previous appointment, thus affecting the schedule and putting pressure on the clinician and the staff [9,10]. Conventional IANB is the most commonly used technique for achieving pulpal anesthesia in posterior mandibular teeth with SIP [5]. Nevertheless, the failure rates recorded with this technique span from 43% to 83% [11,12]. Multiple techniques have been implemented, such as supplemental anesthesia and adjunctive pharmacological strategies that include premedication with acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and opioids, to improve this rate [9]. These approaches have helped to increase the success rate of pulpal anesthesia after an IANB but have never reached 100% success [6,7]. An IANB injection alone had a significantly lower success rate (40%) compared with the other techniques [13]. Several studies have also examined the effectiveness of corticosteroids such as dexamethasone or methylprednisolone on IANB anesthesia success rates [13,14,15]. Dexamethasone and methylprednisolone are the most used corticosteroids in dentistry, but dexamethasone has a longer duration of action and is considered more potent [7,8]. The reports showed that dexamethasone ranked first in increasing the efficacy of anesthesia with an IANB of mandibular posterior teeth with SIP [14], although this approach has not yielded totally successful results [8,9,10]. Previous studies [16,17] have emphasized the possibility of reaching pain relief through a pharmacological approach only, enabling better pain management. A double-blind randomized trial demonstrated the anti-inflammatory effect of a glucocorticoid IO injection and concluded that clinically satisfactory pain relief could be achieved with a pharmacological approach [16]. Another randomized clinical trial compared local methylprednisolone IO injections and emergency pulpotomy in the management of acute pulpitis and showed that a methylprednisolone IO injection, a minimally invasive pharmacological approach, was more effective than the reference treatment, i.e., pulpotomy [12]. Research has suggested the possibility of obtaining similar relief of pulpitis pain by administering oral pharmaceutical agents, including corticoids, combined with long-duration local anesthetics [17]. Yared was the first researcher to introduce the management of SIP with local anesthesia and oral dexamethasone only and without endodontic intervention, at the American Association of Endodontists (AAE) Annual Meeting 2017, New Orleans. One year later, at the AAE Annual Meeting 2018, Denver showed that the emergency treatment of acute irreversible pulpitis in mandibular molars with one IANB of a long-acting anesthetic and a one-day large-dose corticosteroid without a pulpotomy or pulpectomy is a successful technique, and almost 100% of patients will be relieved almost immediately and will remain pain-free for at least one week.

Introducing a medicinal analgesic protocol would allow for the better allocation of limited resources in the clinical settings that offer dental emergency management while enabling doctors with little dental training to handle these emergencies [17]. Dexamethasone is a long-acting corticosteroid commonly used in endodontics in many forms. This molecule presents several advantages, including a pure glucocorticoid effect and virtually no mineralocorticoid effect [18], a bioavailability of 61–86%, and a peak plasma concentration level of 8.4 μg per liter per 1 mg dose after 1.5–2 h [19]. However, the efficacy of short-course orally administered dexamethasone in reducing pain without performing conventional pulpotomy has never been described. Therefore, this clinical study aimed to assess the effectiveness of an IANB injection followed by the administration of oral dexamethasone in reducing the pain associated with SIP in mandibular molars without performing conventional pulpotomy. It also sought to compare these outcomes with the pain experienced following pulpotomy. The null hypothesis was that the combination of an IANB injection with a short-course orally administered corticosteroid has a low or no effect on reducing pain in patients with SIP.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol Approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Saint Joseph University of Beirut (USJ-2022-212, 19 September 2022) and the Ethics Committee of the Beirut Arab University (2022-H-0112-D-R-0490, 24 October 2022). This trial was registered at http://clinicaltrials.gov/ under the registration number: NCT05761730. The registration date is 15 February 2023.

This study adheres to the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) guidelines for non-randomized clinical trials. The study design, methodology, and analysis have been transparently reported, including detailed descriptions of the participant selection, the intervention procedures, the outcome measures, and the statistical analyses. The TREND checklist has been completed to ensure comprehensive and standardized reporting.

2.2. Sample Size

A power analysis was conducted for a repeated-measures analysis of variance(ANOVA), between-subjects factor, using G*Power to determine the sample size. It considered a power of 80%, an alpha of 5%, two study groups, and four measurements while assuming a medium eta-squared of 0.06. The minimum sample size required for this controlled clinical study was 80 patients (40 per group).

2.3. Participants and Settings

Patients presenting with acute SIP-induced pain on a lower mandibular molar and seeking emergency consultation at the dental departments of the Saint-Joseph University of Beirut (USJ) and the Beirut Arab University (BAU) were recruited if they met the eligibility criteria. Only healthy patients were recruited to reduce the selection and measurement bias due to systemic diseases.

2.4. Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria encompassed systemically healthy patients (Category: American Society of Anesthesiologists class 1) (ASA House of Delegates 2014) aged between 18 and 60 years, presenting with mandibular molars diagnosed with SIP and a radiographically normal periapical region without symptomatic apical periodontitis. The diagnosis relied on a clinical and radiographic examination and pulp sensibility testing. The clinical examination included a visual assessment of the tooth and surrounding tissues, periodontal probing, palpation, and percussion tests. Vital pulp status was confirmed before the intervention. The cold test was performed to identify the tooth suffering from SIP. Patients exhibiting an exaggerated and “lingering” response to cold stimulus were included. Teeth with deep occlusal decay, old restoration with underlying decay, recent restoration, or a crown were also included [5]. The inclusion criteria considered patients agreeing to be contacted by phone post-emergency visit until pain relief, those available for a subsequent complete endodontic treatment, and those capable of understanding the study’s informed consent form and pain recording scales.

2.5. Exclusion Criteria

The exclusion criteria comprised teeth with an acute or chronic apical abscess, pulp necrosis, a lack of an adequate contact point, and open apices. Patients with temporomandibular disorders, mental disabilities, or a current or recent history of viral diseases (e.g., hepatitis, herpes zoster, and ocular herpes), tuberculosis, hypertension, renal insufficiency, adrenocortical dysfunction, epilepsy, systemic fungal infections, Guillain–Barré syndrome, peptic ulcers, and gastrointestinal disorders were excluded. Additionally, the exclusion criteria encompassed medically compromised patients, pregnant and lactating women, those with a history of allergy to local anesthetic solutions or any of the experimental drugs, those on long-term medications affecting pain threshold, and those who had taken analgesics, steroids, and/or antibiotics in the past 12 h.

2.6. Treatment Protocol

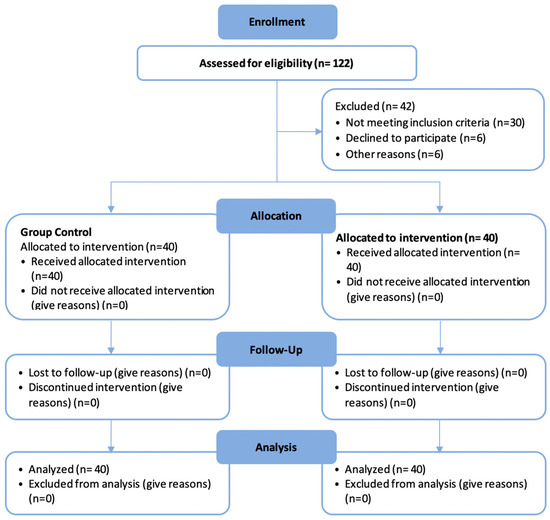

The participants were orally briefed on the study by the same communication operator. All of the details, including the demographic information, medical and dental history, relevant clinical examination, periapical radiographs, age, sex, pulpal status, pain intensity, duration of pain, weight in kg, and height in cm, were recorded in the patients’ charts. Participant allocation to one of the two groups was non-randomized, and practical considerations guided the choice of allocation. In situations allowing for immediate treatment, a pulpotomy was conducted after an IANB. Conversely, patients received an IANB with oral dexamethasone in cases of time or material constraints. The detailed patient flow and allocation procedures are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

CONSORT 2010 diagram showing the patient flow in the study.

Before the injection, the preoperative pain intensity was measured using the 100 mm visual analogue scale (VAS), ranging from 0 (no pain) to 100 (worst pain imaginable) [14]. The ratings were categorized as follows: 1 to 39 mm for mild pain, 40 to 59 mm for moderate pain, 60 to 79 mm for intense pain, and 80 to 100 mm for severe pain.

2.7. Control Group

All patients received standard IANB injections using 1.8 mL 4% articaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine. The examination for the success of the anesthetic blockade initiated by the IANB was based only on the feeling of numbness of the lip expressed by the patient. The access preparation was then initiated under rubber dam isolation. In case of pain during the access preparation, additional anesthesia, such as buccal and intraligamentary injections, was administered. If pulpal anesthesia was not achieved even after all supplemental techniques, intrapulpal anesthesia was considered. The pulpotomy was performed with a large sterile round-end bur in a high-speed handpiece with copious irrigation, and the pulp tissue was removed to the orifice level. The pain was measured at four intervals: (1) at baseline, at the clinic before the pulpotomy; (2) 8 h post-procedure; (3) 12 h post-procedure; and (4) 24 h post-procedure.

2.8. Dexamethasone Group

All patients received standard IANB injections using 1.8 mL 4% articaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine. The examination for the success of the anesthetic blockade initiated by the IANB injection was based only on the feeling of numbness of the lip expressed by the patient. An additional IANB injection was considered if lip numbness was not reported. After successful anesthesia, 4 mg of oral dexamethasone was administered, and the patient was asked to take the provided corticosteroid immediately. Each patient received one oral dose of dexamethasone (4 mg) during the emergency visit and was instructed to take another dose of 4 mg after 8 h. The patient was then dismissed, and a follow-up telephone call assessed whether the patient took the second dose of dexamethasone, inquired about pain incidence during the same day until pain relief, and recorded any adverse events or symptoms. The pain was measured at four points: (1) at baseline, at the clinic, when the patient presented with pain; (2) 8 h post-first dose; (3) 12 h post-first dose; and (4) 24 h post-first dose. The postoperative pain intensity was measured using the VAS. All patients were instructed to record their pain levels on the VAS in a pain diary at 8, 12, and 24 h following the procedure. Once the intervention was completed, patients were instructed not to take any medication and to call the operator if they experienced an increase in pain intensity that warranted emergency treatment. All patients were contacted by telephone to evaluate the pain incidence after 8, 12, and 24 h. A second visit, scheduled five to six days after the date of the initial visit, was planned for each patient to undergo a complete endodontic treatment.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The level of significance was set at 5% and all tests were two-tailed. Descriptive statistics of the quantitative variables were calculated and presented as means ± standard deviations and medians (interquartile ranges) since they did not follow a normal distribution as determined by the Shapiro–Wilk test, and categorical variables were presented as frequencies (percentages). To compare the distribution of the qualitative variables between groups, Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used; and to compare the distribution of the quantitative variables, the Mann–Whitney U test was used. To compare the pain scores between groups at the same time point, the Mann–Whitney U test was used, and to compare the pain scores between the four time points within the same intervention group, the Friedman’s test was used followed by the Bonferroni correction for multiple pairwise comparisons. Success was determined when the pain score on the VAS was 20 or lower. A survival analysis was conducted where the event was considered as the disappearance of symptoms (or success: pain score ≤ 20); the survival data were compared between the intervention groups using the log rank test and were plotted using Kaplan–Meier curves. The median survival times and their 95% confidence intervals were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. The effects of the study variables on the occurrence of the event were assessed through univariate survival analysis using the Cox regression, and the variables (initial pain score and BMI) with a p-value of 0.1 or less were entered into the multivariate Cox regression model along with the intervention groups and possible confounder (tooth type). The hazard ratios (HR) and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated and reported.

3. Results

Eighty patients participated in this clinical study, divided equally between the intervention groups, with a mean age of 32.95 ± 8.82 years ranging from 18 to 60 years. There were 41 (51.2%) males and 39 (48.8%) females.

Table 1 presents the distribution of the baseline characteristics for the study groups and the overall sample. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups regarding sex, age, initial pain score, and BMI (p > 0.05). The distribution of second and third molars was significantly different between groups (p < 0.05): 45% and 2.5% of the teeth were second and third molars in the dexamethasone group compared to 15% and 17.5% in the control group, respectively.

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics between groups.

The comparisons of pain scores between time points within the same intervention group, and between groups at the same time point, are shown in Table 2. For both groups, the pain had significantly decreased 8 h postoperatively (p < 0.05), and no significant differences were observed between 8, 12, and 24 h after the interventions (p > 0.05). Although the pain scores were greater in the control group compared to the dexamethasone group at 8, 12, and 24 h postoperatively, these differences were not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

Table 2.

Pain scores among groups preoperatively and at 8, 12, and 24 h postoperatively.

Table 3 displays the comparison of the success rates between both intervention groups at 8, 12, and 24 h postoperatively. At 8 and 12 h, the success rates were significantly greater in the dexamethasone group (97.5% and 100%) compared to the control group (82.5% and 87.5%) (p = 0.05). At 24 h, although the success rate was slightly greater in the dexamethasone group compared to the control group, the difference was not statistically significant (95% vs. 87.5%; p = 0.432).

Table 3.

Success rates among groups at 8, 12, and 24 h postoperatively.

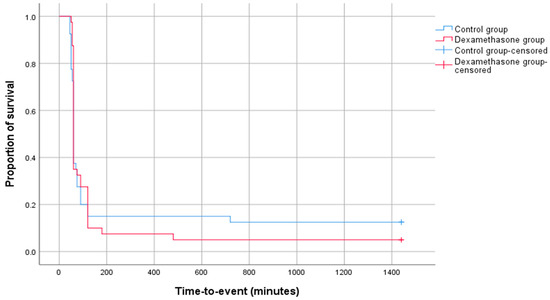

The log rank test was used to compare the survival curves of the dexamethasone and control groups. There were 38 events out of 40 in the dexamethasone group and 35 events out of 40 in the control group. The log rank test statistic was 0.086 with 1 degree of freedom (df). The p-value was 0.769, indicating a non-significant difference in survival between the two groups. The survival curves for both groups are shown in Figure 2. The median survival time for the dexamethasone group was 60 min (95% CI: 58.59–61.41 min), and the median survival time for the control group was 60 min (95% CI: 57.86–62.14 min).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier graph showing survival curves for both intervention groups.

Table 4 displays the results of the Cox regression analysis with unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HR) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) and p-values. The aim of the analysis was to identify the association between several variables and the outcome of interest, which is the disappearance of symptoms. Only the initial pain score was a significant predictor of the outcome variable in both the unadjusted (p = 0.020) and adjusted models (p = 0.037). The results indicate that for each unit increase in the initial pain score, the chance of symptom disappearance decreased by 2.3% in the unadjusted model and by 2.1% in the adjusted model.

Table 4.

Results of univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses on pain disappearance events.

4. Discussion

This study primarily aimed to assess the effect of oral dexamethasone after an IANB on reducing pain in mandibular molars with SIP without performing conventional pulpotomy, compared with the pain following pulpotomy. A significant decrease in pain was observed when the participants were premedicated with dexamethasone after anesthesia in the dental office. Thus, the null hypothesis was rejected. Often, patients with SIP requiring emergency dental care exhibit a high prevalence of dental anxiety [20], which could be linked to pain before treatment. A survey among dental patients has highlighted pain, needles, difficulty in achieving anesthesia, and anxiety as the primary causes of fear [21]. Patients seeking pain relief are often apprehensive about the potential discomfort during the evaluation and treatment process [20]. In the present study, for the patients who received dexamethasone, the procedure was explained as an effective pain and anxiety management strategy: “No drilling of the tooth nor extirpation of the pulp will be performed”.

Only standard IANB injections were used to convey a sense of care, relief, and reassurance to the patient that they could achieve successful anesthesia. Anesthesia brings significant pain alleviation in anxious patients experiencing SIP while also contributing to psychological relief [20]. In this study, the pain was evaluated using the 100 mm VAS, with the mean initial pain across groups recorded at 89.13, indicating severe pain. Most importantly, the success rates with oral dexamethasone at 8 and 12 h were significantly higher in the dexamethasone group (97.5% and 100%) compared with the control group (82.5% and 87.5%) (p = 0.05). At 24 h, although the success rate was slightly higher in the dexamethasone group, the difference was not statistically significant (95% vs. 87.5%; p = 0.432). Control groups are usually used to evaluate the efficacy of medications. This study found no statistically significant differences between the control and intervention groups regarding sex, age, initial pain score, and BMI. Therefore, these variables are unlikely to have influenced the results, allowing for a robust comparison between the groups. The current trial included patients aged between 18 and 60 years old, which might affect the generalizability of the results to patients beyond 60 years of age. Several studies have evaluated the effect of pre-administration of dexamethasone on the success rate of IANB, showing the superiority of dexamethasone over other drugs [13,14,22,23]. However, the present study is the first to evaluate pain control in patients with SIP in a mandibular molar after an IANB and the administration of oral dexamethasone. Dexamethasone, widely used in various forms in endodontics, was administered orally in the present study due to its convenience, clinical effectiveness, and consideration for patients who may struggle with intramuscular and intravenous injections, which are often associated with discomfort, anxiety, and needle phobia. The time until the disappearance of symptoms was recorded in both groups and the pain was assessed on the VAS at extended intervals to reflect the sustained efficacy of dexamethasone beyond the dental office. The pain intensity decreased significantly after 24 h in the dexamethasone group, a result possibly attributed to the long biological half-life of dexamethasone, ranging from 36–72 h [19]. No adverse effects were observed following the treatment with dexamethasone, consistent with prior findings [23,24]. This study reaffirms that a single, even large, dose of dexamethasone is generally without harmful effects, and a short course of therapy of up to one week in the absence of specific contraindications is unlikely to pose harm [18].

In this study, three patients chose not to return for endodontic treatment after receiving the dexamethasone. Upon being called, these patients expressed that they no longer wished to pursue further treatment as the premedication had alleviated their pain. A similar trend was reported in a previous study [15], where ibuprofen and/or dexamethasone were administered to participants with SIP on mandibular molars one hour before performing standard IANB injections; four patients decided not to wait for the IANB injection and did not proceed with the planned endodontic intervention after taking the medication. The pain was significantly reduced in both groups after 8 h (p < 0.05), and no significant difference was observed between 8, 12, and 24 h, indicating that dexamethasone was as effective as conventional pulpotomy. The results showed that for each unit increase in the initial pain score, the chance of symptom disappearance decreased by 2.3%, which is clinically insignificant.

While dexamethasone has shown significant efficacy in reducing pain associated with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis [15], it should be considered as an adjunct to local anesthesia rather than a replacement for pulpotomy. Corticosteroids, including dexamethasone, are known for their potent anti-inflammatory properties [18], which can enhance the effectiveness of IANB anesthesia by reducing inflammatory mediators responsible for nerve sensitization. Pre-administration of dexamethasone before anesthesia may improve anesthetic success rates in cases of severe pulpitis, where achieving profound anesthesia is often challenging. However, it is crucial to emphasize that while dexamethasone provides temporary pain relief, it does not address the underlying pathology, and definitive endodontic treatment remains necessary to ensure long-term success.

In an attempt to standardize the data and facilitate the correlation between analgesic use and postoperative discomfort or change in pain, the patients were instructed to call the operator in cases of severe pain instead of taking any analgesic. Importantly, all patients met the enrollment criterion of not having received analgesics or other drugs in the 12 h preceding their procedure. This enrollment criterion was crucial as oral steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have been demonstrated to significantly reduce postoperative pain [25]. Out of the 80 patients, 77 returned for conventional root canal treatment after five to six days as scheduled. Notably, there were no unscheduled visits to the dental clinic for emergency reasons between the appointments, demonstrating the absence of unexpected events.

This trial has some limitations. The study sample size is a noteworthy limitation. The initially calculated sample of 80 was based on a bivariate analysis with a medium effect size, restricting the capacity for a robust multivariate analysis. Consequently, the absence of a significant difference between the two groups could be attributed to this limitation. Moreover, a potentially smaller effect size between the groups may further contribute to the lack of significant differences observed. Despite the usefulness of the VAS in evaluating pain, the perception of pain is a personal and subjective encounter. The VAS is subjective and patient-dependent, which may introduce variability in pain reporting. The absence of blinding in our study introduces potential bias, as both the participants and the researchers were aware of the treatment conditions. Incomplete or inaccurate data recording by patients at regular intervals could have influenced the results. Thus, an alternative worth exploring in future larger-size clinical studies is the use of an electronic approach for pain measurement [26]. Another possible limitation is that the inclusion was limited to participants with SIP; hence, the findings cannot be extended to patients with apical periodontitis and pulpal necrosis. The lack of randomization is a limitation, as it may introduce selection bias. Future studies should aim for randomized controlled designs to improve the validity of the findings.

In specific circumstances, such as anesthetic failure, characterized by intense pain hindering access to the pulp, the oral administration of dexamethasone emerges as a valuable strategy to temporarily alleviate SIP symptoms until definitive treatment becomes feasible. This approach proves particularly effective when emergency dental care is inaccessible due to factors like pandemics (e.g., COVID-19), wartime situations, or a temporary geographical distance between the patient and the dentist.

5. Conclusions

Dexamethasone has demonstrated significant pain relief in cases of symptomatic irreversible pulpitis; however, it should not be considered a substitute for conventional pulpotomy. Instead, it may serve as an effective temporary pain management strategy when immediate endodontic treatment is not feasible. Future research should aim to refine dexamethasone’s clinical use by optimizing its dosage, assessing its long-term impact, and exploring combination treatments to enhance its efficacy while minimizing the potential systemic risks. Additionally, the development of patient-specific guidelines for corticosteroid use in emergency dental care may further support its integration into clinical practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.E.H. and R.A.; methodology, S.C., R.Z. and R.C.; software, S.C., R.Z. and R.C.; validation, P.S., H.S., R.B. and N.K.; formal analysis, L.N.; investigation, P.S., H.S., R.B. and N.K.; resources, R.A.; data curation, R.E.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C., P.S. and H.S.; writing—review and editing, R.A., R.E.H., N.K., L.H. and R.B.; visualization, N.K., L.H. and R.B.; supervision, R.E.H.; project administration, R.E.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Saint Joseph University of Beirut (USJ-2022-212, 19 September 2022) and the Ethics Committee of the Beirut Arab University (2022-H-0112-D-R-0490, 24 October 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abbott, P.; Yu, C. A Clinical Classification of the Status of the Pulp and the Root Canal System. Aust. Dent. J. 2007, 52, S17–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulip, D.E.; Palmer, N.O.A. A Retrospective Investigation of the Clinical Management of Patients Attending an Out-of-Hours Dental Clinic in Merseyside under the New NHS Dental Contract. Br. Dent. J. 2008, 205, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eghbal, M.J.; Asgary, S.; Baglue, R.A.; Parirokh, M.; Ghoddusi, J. MTA Pulpotomy of Human Permanent Molars with Irreversible Pulpitis. Aust. Endod. J. 2009, 35, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselgren, G.; Reit, C. Emergency Pulpotomy: Pain Relieving Effect with and without the Use of Sedative Dressings. J. Endod. 1989, 15, 254–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claffey, E.; Reader, A.; Nusstein, J.; Beck, M.; Weaver, J. Anesthetic Efficacy of Articaine for Inferior Alveolar Nerve Blocks in Patients with Irreversible Pulpitis. J. Endod. 2004, 30, 568–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, V.; Singla, M.; Kabi, D. Comparative Evaluation of Effect of Preoperative Oral Medication of Ibuprofen and Ketorolac on Anesthetic Efficacy of Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block with Lidocaine in Patients with Irreversible Pulpitis: A Prospective, Double-Blind, Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Endod. 2010, 36, 375–378. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, R.E.; Torabinejad, M. Managing Local Anesthesia Problems in the Endodontic Patient. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1992, 123, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias-Junior, L.C.d.L.; Bezerra, A.P.; Schuldt, D.P.V.; Kuntze, M.M.; de Luca Canto, G.; da Fonseca Roberti Garcia, L.; da Silveira Teixeira, C.; Bortoluzzi, E.A. Effectiveness of Different Anesthetic Methods for Mandibular Posterior Teeth with Symptomatic Irreversible Pulpitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 6477–6500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, P.V. Present Status and Future Directions: Managing Endodontic Emergencies. Int. Endod. J. 2022, 55 (Suppl. S3), 778–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrotte, P. Endodontics: Part 3. Treatment of Endodontic Emergencies. Br. Dent. J. 2004, 197, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaviani, N.; Khademi, A.; Ebtehaj, I.; Mohammadi, Z. The Effect of Orally Administered Ketamine on Requirement for Anesthetics and Postoperative Pain in Mandibular Molar Teeth with Irreversible Pulpitis. J. Oral Sci. 2011, 53, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lammers, E.; Nusstein, J.; Reader, A.; Drum, M.; Beck, M.; Fowler, S. Does the Combination of 3% Mepivacaine Plain Plus 2% Lidocaine with Epinephrine Improve Anesthesia and Reduce the Pain of Anesthetic Injection for the Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block? A Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind Study. J. Endod. 2014, 40, 1287–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-de la Torre, L.; Gómez-Sánchez, E.; Serafín-Higuera, N.A.; Alonso-Castro, Á.J.; López-Verdín, S.; Molina-Frechero, N.; Granados-Soto, V.; Isiordia-Espinoza, M.A. Dexamethasone Increases the Anesthetic Success in Patients with Symptomatic Irreversible Pulpitis: A Meta-Analysis. Pharmaceutics 2022, 15, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegde, V.; Shanmugasundaram, S.; Shaikh, S.; Kulkarni, V.; Suresh, N.; Setzer, F.C.; Nagendrababu, V. Effect of Preoperative Oral Steroids in Comparison to Anti-Inflammatory on Anesthetic Success of Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block in Mandibular Molars with Symptomatic Irreversible Pulpitis—A Double-Blinded Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Endod. 2023, 49, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Singla, R.; Gill, G.S.; Kalra, T.; Jain, N. Evaluating Combined Effect of Oral Premedication with Ibuprofen and Dexamethasone on Success of Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block in Mandibular Molars with Symptomatic Irreversible Pulpitis: A Prospective, Double-Blind, Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Endod. 2021, 47, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallatin, E.; Reader, A.; Nist, R.; Beck, M. Pain Reduction in Untreated Irreversible Pulpitis Using an Intraosseous Injection of Depo-Medrol. J. Endod. 2000, 26, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bane, K.; Charpentier, E.; Bronnec, F.; Descroix, V.; Gaye-N’Diaye, F.; Kane, A.W.; Toledo, R.; Machtou, P.; Azérad, J. Randomized Clinical Trial of Intraosseous Methylprednisolone Injection for Acute Pulpitis Pain. J. Endod. 2016, 42, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, R.E.; Throndson, R.R. A Review of Perioperative Corticosteroid Use in Dentoalveolar Surgery. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2000, 90, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.M. Clinical Pharmacology of Corticosteroids. Respir. Care 2018, 63, 655–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, L.; Vanschaayk, M.M.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, X.; Ji, P.; Yang, D. The Prevalence of Dental Anxiety and Its Association with Pain and Other Variables among Adult Patients with Irreversible Pulpitis. BMC Oral Health 2018, 18, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, Y.K.; Montagnese, T.A.; Harding, J.; Aminoshariae, A.; Mickel, A. Assessment of Patients’ Awareness and Factors Influencing Patients’ Demands for Sedation in Endodontics. J. Endod. 2015, 41, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahi, S.; Mokhtari, H.; Rahimi, S.; Yavari, H.R.; Narimani, S.; Abdolrahimi, M.; Nezafati, S. Effect of Premedication with Ibuprofen and Dexamethasone on Success Rate of Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block for Teeth with Asymptomatic Irreversible Pulpitis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Endod. 2013, 39, 160–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bidar, M.; Mortazavi, S.; Forghani, M.; Akhlaghi, S. Comparison of Effect of Oral Premedication with Ibuprofen or Dexamethasone on Anesthetic Efficacy of Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block in Patients with Irreversible Pulpitis: A Prospective, Randomized, Controlled, Double-Blind Study. Bull. Tokyo Dent. Coll. 2017, 58, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suresh, N.; Nagendrababu, V.; Koteeswaran, V.; Haritha, J.S.; Swetha, S.D.; Varghese, A.; Natanasabapathy, V. Effect of Preoperative Oral Administration of Steroids in Comparison to an Anti-Inflammatory Drug on Postoperative Pain Following Single-Visit Root Canal Treatment—A Double-Blind, Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. Endod. J. 2021, 54, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalalzadeh, S.M.; Mamavi, A.; Shahriari, S.; Santos, F.A.; Pochapski, M.T. Effect of Pretreatment Prednisolone on Postendodontic Pain: A Double-Blind Parallel-Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Endod. 2010, 36, 978–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassman, G.; Krasner, P.; Morse, D.R.; Rankow, H.; Lang, J.; Furst, M.L. A Prospective Randomized Double-Blind Trial on Efficacy of Dexamethasone for Endodontic Interappointment Pain in Teeth with Asymptomatic Inflamed Pulps. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1989, 67, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).