1. Introduction

Montgomery´s medialization thyroplasty is a laryngeal frame surgery whose objective is to treat patients with dysphonia and dysphagia due to unilateral vocal cord paralysis [

1]. This procedure was designed to be a simplified implant technique to medialize the paralyzed vocal cord; it provides a step-by-step surgical approach along with silicone implants in six sizes (Boston Medical Products

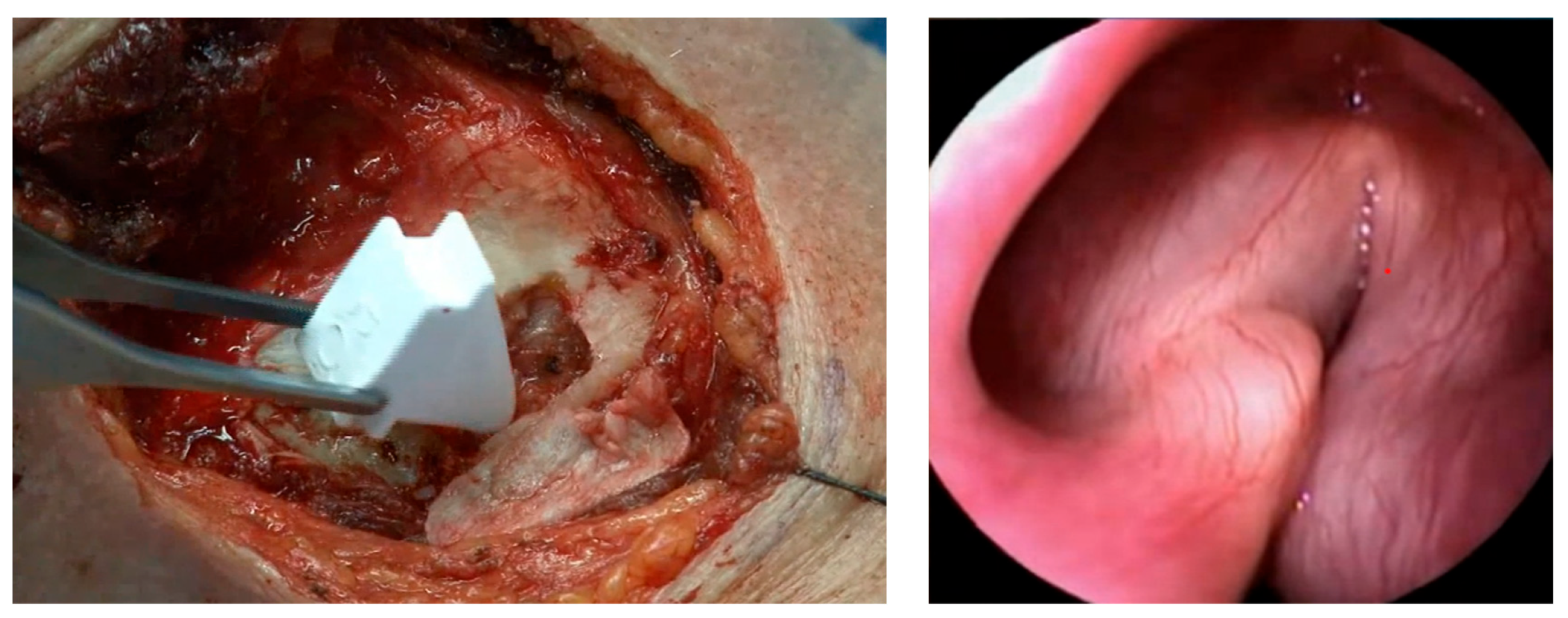

®). The range of sizes differs for male and female patients. The surgeon determines the prosthesis size by monitoring the patient’s vocal changes during the surgical procedure under local anesthesia and sedation. Different sizes of phantom prostheses are inserted through the thyroid cartilage window and then the surgeon asks the patient to speak and checks their voice quality. We developed a modified procedure using a specific caliper designed by the final author (JMO, Barcelona, Spain) and performed the surgery under general anesthesia in order to minimize patient discomfort and to personalize the location and size of the prosthesis via fibroscopic monitoring of the larynx (

Figure 1). These modifications improved our results, with optimal medialization of the paralyzed cord being achieved [

2,

3].

The morbidity of this technique is low and, as we showed in a multicentric study, its long-term results are generally good [

4]. However, some patients have persistent dysphonia and/or aspirations. In these cases, the therapeutic strategy is complex and includes various surgical techniques such as the replacement of the prosthesis and arytenoid adduction [

5]. All of these treatments aim to close the glottic gap.

The results can be suboptimal in some female patients because of differences in female and male laryngeal anatomy. The angle formed by the thyroid cartilage is greater in women than in men, meaning that the posterior portion of this cartilage is further away from the midline in women [

6]. The prostheses available for women in the Montgomery set range between size numbers 6 and 11 while those for men are numbered 8 to 13. Nevertheless, as described in the present study, we used male prostheses to improve suboptimal results in some of our female patients.

2. Materials and Methods

Study design: This was a retrospective case series study. We included all of the female individuals undergoing medialization thyroplasty reintervention using male Montgomery thyroplasty prostheses performed in the Otolaryngology Department at the General University Hospital of Valencia from 2014 to 2024.

Ethical considerations: All of the patients included in this study were given information about the characteristics of this surgical technique and the off-label use of male prosthesis, and we obtained their written informed consent for participation. The study design was approved by the ethics committee of our institution (project reference: 110/2021).

All of the surgical procedures were carried out by the final author and the same anesthesiologist. Post-operative rehabilitation treatment was completed in every case.

We developed a method to intraoperatively adjust and personalize the location of the implant by using a device to improve the precision of the method. This system is based on two principles: (1) the use of general anesthesia with a laryngeal mask and monitoring of the glottis with a fibrolaryngoscope through the mask [

7]; we have previously demonstrated the influence of sedation on voice quality [

8,

9]; (2) customization of the cartilage window, depending on the individual anatomy. Compared to the Montgomery recommendations, our results improved when following this modified method [

3,

10].

The symptoms of dysphonia affecting daily life and dysphagia causing aspiration persisted after primary thyroplasty in all of the cases included in this case series. As shown in

Table 1, two of the patients had swallowing problems as a result of previous esophageal surgery (patient 1) or vagal glomus surgery (patient 3). A laryngoscopy confirmed incomplete glottal closure in all of these cases. Furthermore, a computed tomography scan was also performed on all of the patients to confirm adequate placement of the female prostheses.

In this case series, we used male prostheses number 11 or 12 during secondary thyroplasty to achieve glottal closure. We collected data on the patients’ age and the prosthesis size used. Functional results were studied using voice aerodynamic parameters: maximum phonation time (MPT), voice evaluation using the GRBAS scales [

11] (grade, roughness, breathiness, asthenia, and strain), and two questionnaires: Voice-Handicap Index 30 (VHI-30) [

12] and Eating Assessment Tool 10 (EAT-10) [

13]. These tests were performed by the same ENT in all of the cases.

3. Results

We performed medialization thyroplasty in four patients who were reoperated to replace the female prosthesis with a male one between 2014 and 2024. The mean patient age was 34 years. The phonatory and swallowing results for these women before and after the secondary thyroplasty are summarized in

Table 1. Two patients (cases 1 and 3) had deglutition problems, and case 3 presented hypoglossal nerve paralysis after glomus surgery. All of the patients improved after the secondary thyroplasty. Of note, in patient case 3, the MPT parameter did not change but their VHI-30 and GRABAS scores significantly improved.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of the use of a male Montgomery prosthesis in female patients. In 75% of these patients who required reintervention, the paralysis had been caused by a vagus nerve injury, which is a factor of worse evolution due to the loss of sensory innervation combined with motor failure [

14].

The choice of taking a surgical approach to manage unsatisfactory results after primary thyroplasty should be personalized based on patient characteristics and the preferences of the surgeon. Arytenoid adduction is a surgical alternative used to solve unilateral vocal cord paralysis but is a technically challenging procedure. In our patients, prosthesis repositioning surgery was a less invasive and safer alternative.

Significant anatomical differences between the male and female larynx have been widely described in the academic literature [

6,

15]. These sex-related differences in the absolute dimensions on the thyroid surface are the result of pubertal anteroposterior growth of the male larynx and different angulation between the thyroid cartilage alae. Even though the size of the female cartilage may be smaller, a greater distance between the thyroid cartilage and midline can be created by angulation, thereby indicating that the use of larger prostheses could be required.

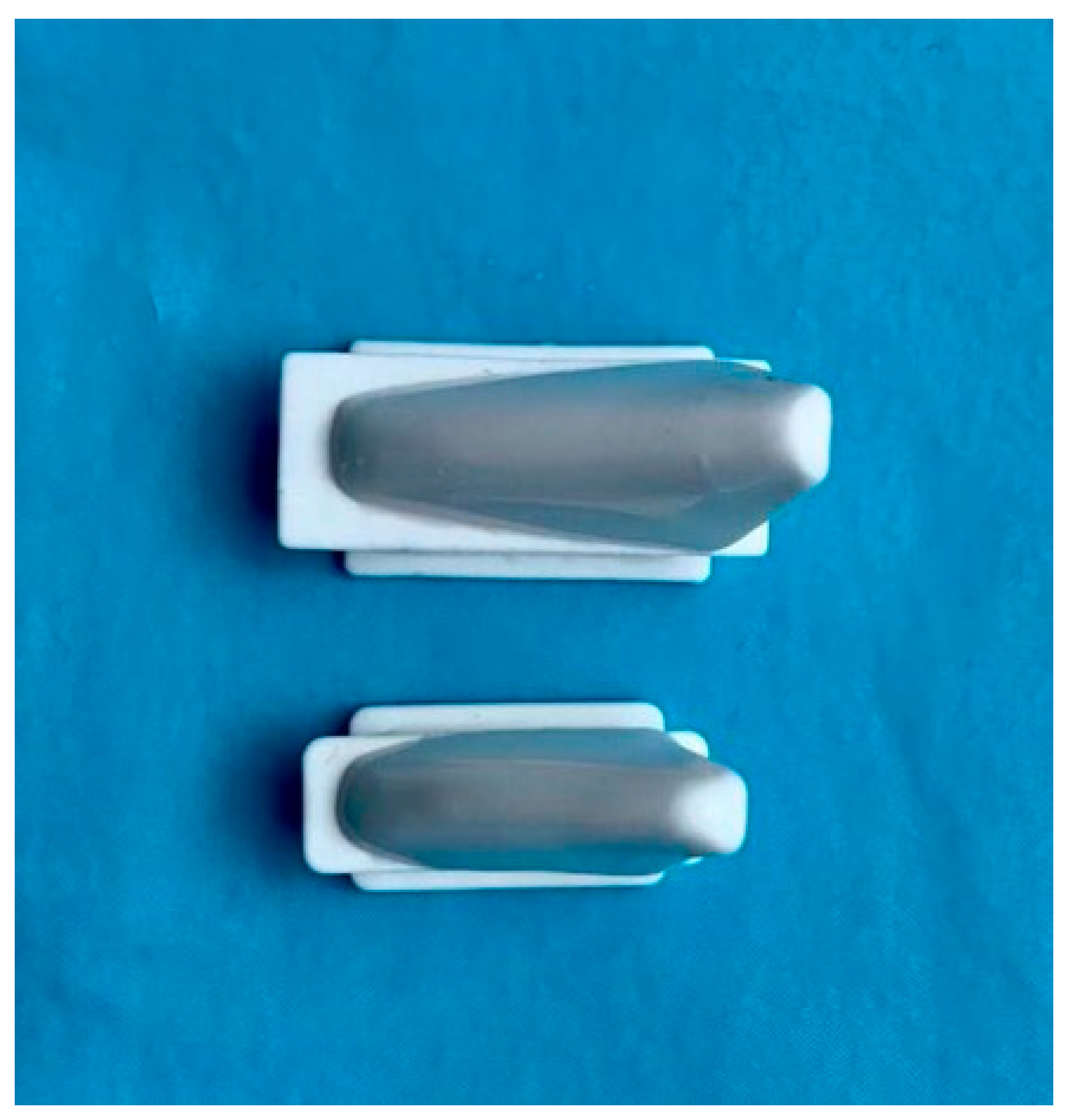

As shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, the male implant was larger and reached a greater endolaryngeal depth, especially in the posterior region. This would explain the improvement we saw when using the male implant in female patients (

Table 1). In our analysis, we compared the functional results with those from the primary thyroplasty. In all cases, the aerodynamic parameter (MPT) improved, except for case 3. This was the patient with severe vagal nerve damage and who also presented hypoglossal nerve paralysis. However, the VHI-30 score significantly decreased in all of the cases, indicating an improvement in patient satisfaction.

To date, we have had no cases of vocal cord epithelial rupture or extrusion. This study reinforces the idea that the surgical treatment of patients with vocal cord paralysis should be personalized, regardless of their gender. The prosthesis design could be improved in the near future using 3D printing technology based on axial tomography.

5. Conclusions

Our study includes four especially complex cases, which is a small number; however, our result showed that employing male Montgomery implants in women can be a useful tool to achieve the desired improvement in female thyroplasty reintervention. Prosthesis repositioning surgery is a minimally invasive and safe alternative.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.Z.; methodology, S.O.-N.; writing—original draft preparation, N.O.; writing—review and editing, E.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the General University Hospital of Valencia for studies involving humans. Project reference: 110/2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Montgomery, W.W.; Montgomery, S.K. Montgomery thyroplasty implant system. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. Suppl. 1997, 170, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zapater, E.; García-Lliberós, A.; López, I.; Moreno, R.; Basterra, J. A new device to improve the location of a Montgomery thyroplasty prosthesis. Laryngoscope 2014, 124, 1659–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapater, E.; Oishi, N.; Rodríguez-Prado, C.; Hernández-Sandemetrio, R.; Granell, M. Modified Montgomery thyroplasty: Customization of the cartilage window according to laryngeal anatomy. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2024, 45, 104142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desuter, G.; Zapater, E.; Van der Vorst, S.; Henrard, S.; van Lith-Bijl, J.T.; van Benthem, P.P.; Sjögren, E.V. Very long-term Voice Handicap Index Voice Outcomes after Montgomery Thyroplasty: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2018, 43, 1097–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, P. Arytenoid adduction and medialization laryngoplasty. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2000, 33, 817–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desuter, G.; Henrard, S.; Van Lith-Bijl, J.T.; Amory, A.; Duprez, T.; van Benthem, P.P.; Sjögren, E. Shape of Thyroid Cartilage Influences Outcome of Montgomery Medialization Thyroplasty: A Gender Issue. J. Voice 2017, 31, 245.e3–245.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granell, M.; Martín, A.; Oishi, N.; Gimeno Coret, M.; Zapater, E. Anesthetic Technique and Functional Outcomes in Modified Montgomery Thyroplasty. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oishi, N.; Herrero, R.; Martin, A.; Basterra, J.; Zapater, E. Is testing the voice under sedation reliable in medialization thyroplasty? Logop. Phoniatr. Vocol. 2016, 41, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín, A.; De Andrés, J.; Oishi, N.; Granell, M.; Hernández, R.; Otero, M.; Zapater, E. Is Sedation of Choice in Thyroplasty Surgery? A Study on the Effects of Sedatives on Voice Quality. J. Voice 2023, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Zapater, E.; Basterra, J.; López, I.; Oishi, N.; García-Lliberós, A. Use of individual anatomical variations to customise window location in montgomery implant thyroplasty: A case series study. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2019, 44, 1162–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano, M. Clinical examination of voice. In Disorders of Human Communication; Arnold, G.E., Winckel, F., Wyke, B.D., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1981; pp. 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, B.H.; Johnson, A.; Grywalski, C.; Silbergleit, A.; Jacobson, G.; Benninger, M.S.; Newman, C.W. The Voice Handicap Index (VHI). Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 1997, 6, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belafsky, P.C.; Mouadeb, D.A.; Rees, C.J.; Pryor, J.C.; Postma, G.N.; Allen, J.; Leonard, R.J. Validity and reliability of the Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10). Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2008, 117, 919–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, T.J.; Tam, Y.Y.; Courey, M.S.; Li, H.Y.; Chiang, H.C. Unilateral high vagal paralysis: Relationship of the severity of swallowing disturbance and types of injuries. Laryngoscope 2011, 121, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jotz, G.P.; Stefani, M.A.; Pereira da Costa Filho, O.; Malysz, T.; Soster, P.R.; Leão, H.Z. A morphometric study of the larynx. J. Voice 2014, 28, 668–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).