β-Alanine Is an Unexploited Neurotransmitter in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Quality of Assessment

3. Biochemistry of β-Alanine

3.1. Biosynthesis of β-Alanine

3.2. Transport of β-Alanine into Skeletal Muscle and Cardiac Tissue

3.3. Transport of β-Alanine into the Brain

3.4. Biodegradation of β-Alanine

3.5. Carnosine and Its Connection to β-Alanine

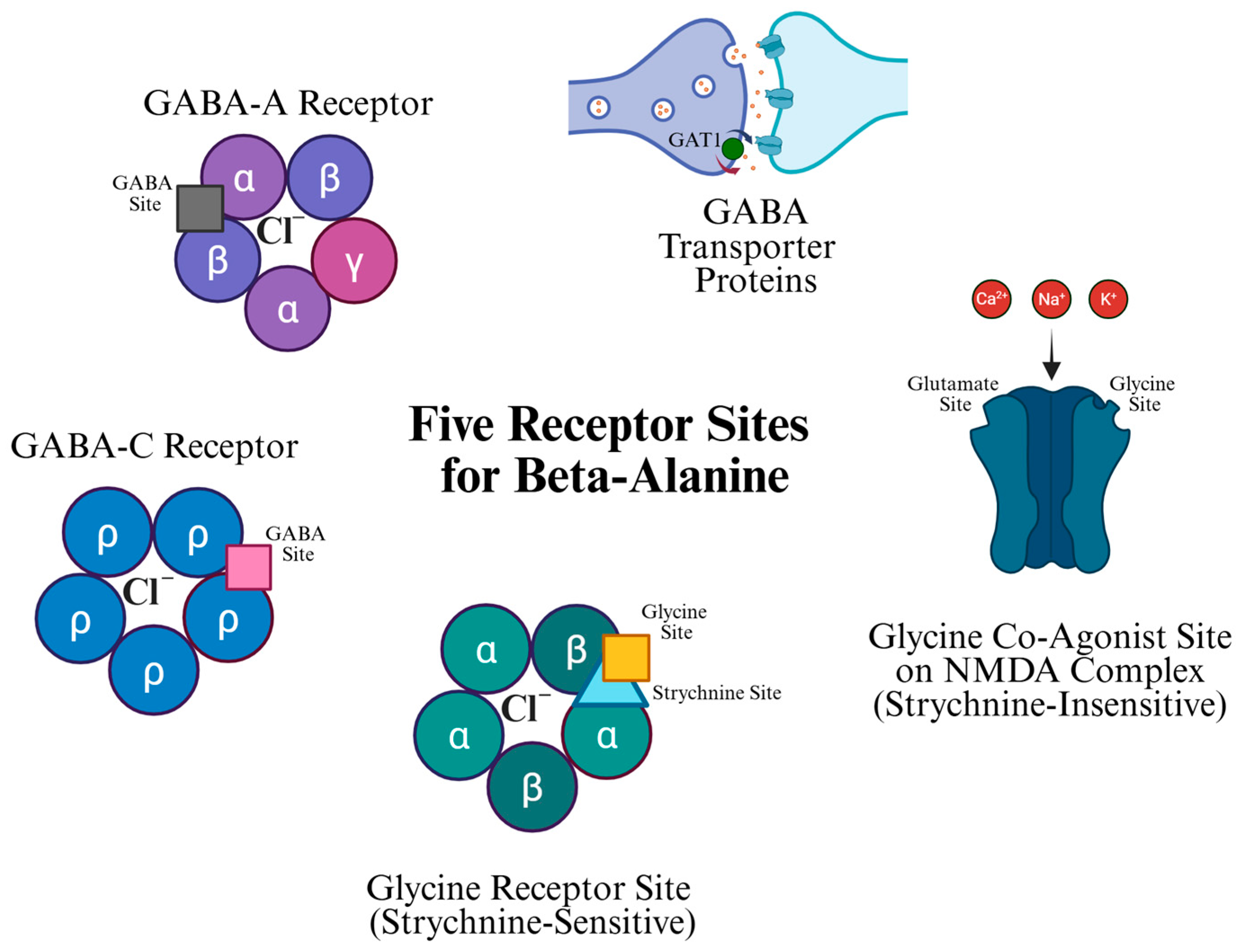

4. β-Alanine Receptor Sites

4.1. Glycine Co-Agonist Site on the NMDA Complex (Strychnine-Insensitive)

4.2. Glycine Receptor Site (Strychnine Sensitive)

4.3. GABA-A and GABA-C Receptors

4.4. GABA Transporter (GAT) Protein-Mediated Glial GABA Uptake

5. β-Alanine as a Neurotransmitter

- (1)

- Existence of inactivating enzyme(s);

- (2)

- Existence of the transmitter in neural tissues;

- (3)

- Ability for storage of the transmitter in neural tissues;

- (4)

- Existence of synthesizing enzyme(s);

- (5)

- Existence of precursor molecules of the transmitter;

- (6)

- Existence of a release mechanism and site of action for the transmitter;

- (7)

- Identical actions among endogenous and exogenous transmitter;

- (8)

- Pharmacological identity with other chemical substances.

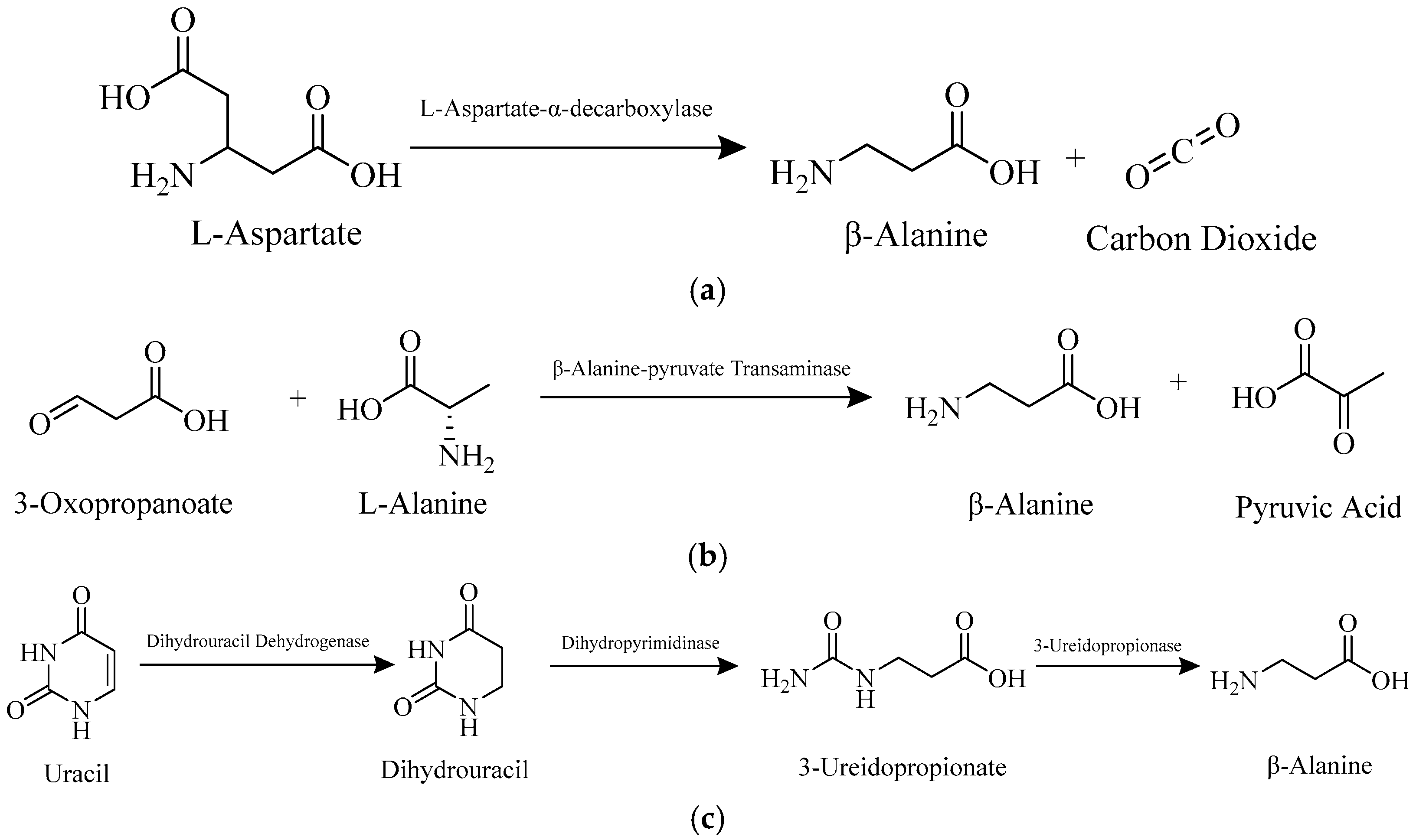

5.1. Existence of Precursor Molecules and Synthesizing and Inactivating Enzyme(s)

5.2. Existence and Storage of the Transmitter in Neural Tissues

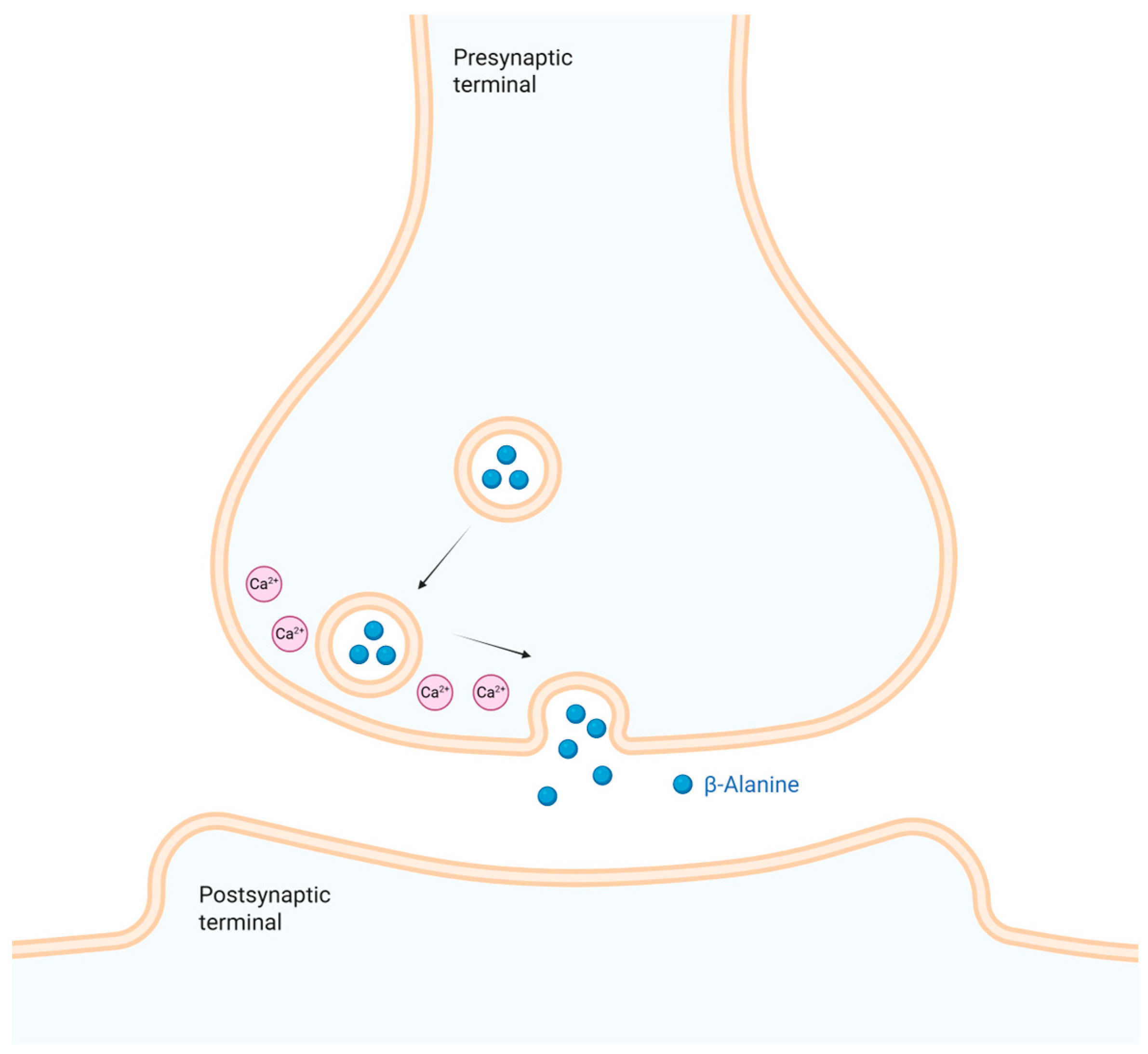

5.3. Existence of a Release Mechanism and Site of Action for the Transmitter

5.4. Identical Actions Among Endogenous and Exogenous Transmitter

5.5. Pharmacological Identity with Other Chemical Substances

5.6. β-Alanine Functions as a Neurotransmitter

6. β-Alanine Supplementation for Exercise Capacity and Cognitive Function

6.1. β-Alanine Supplementation in Humans

6.2. β-Alanine and Carnosine Concentration Changes with Age

6.3. Consequences of Deficiency of β-Alanine and Carnosine in the CNS

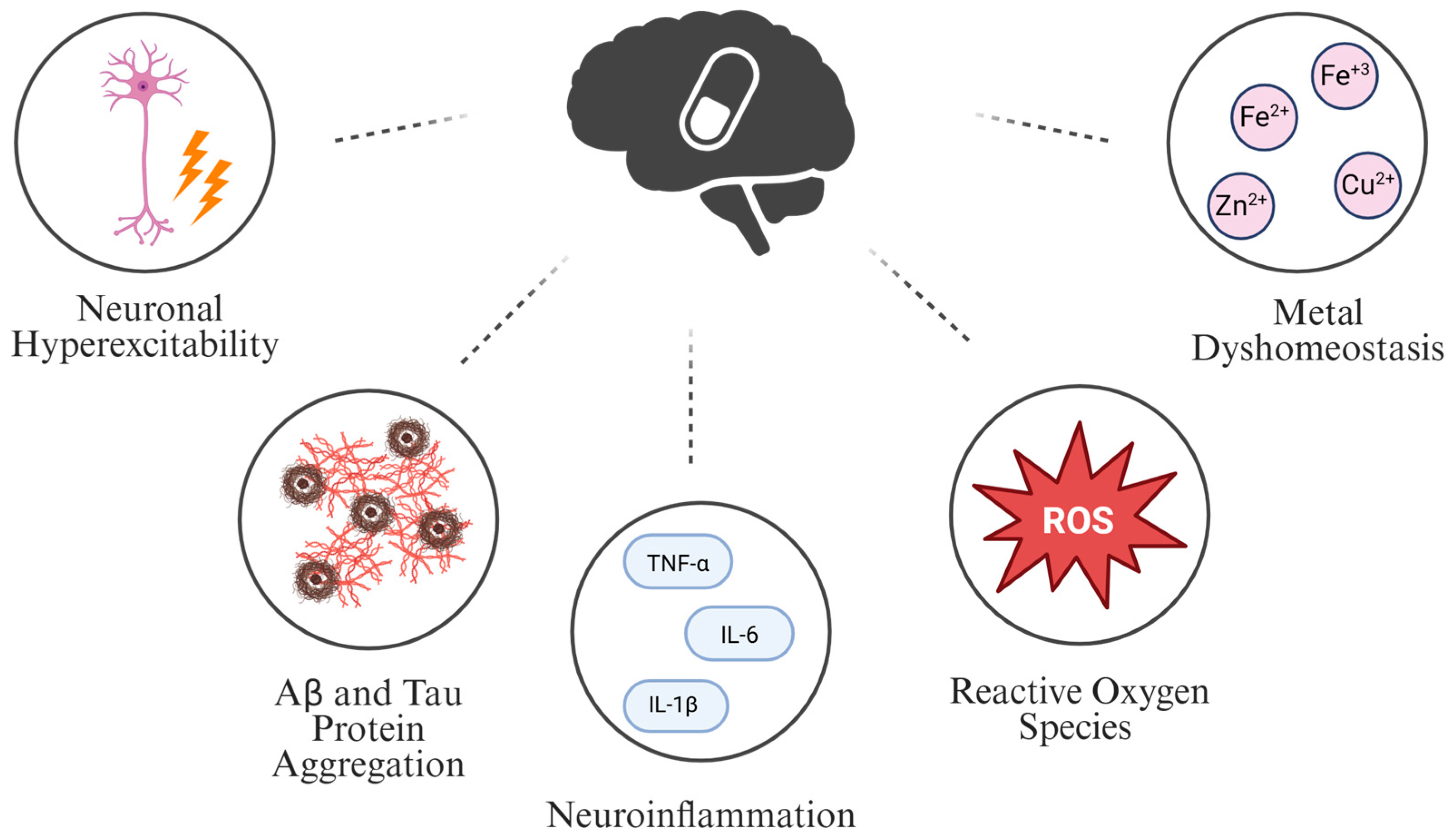

7. β-Alanine Role in Pathogenesis and Possible Treatment of AD

7.1. Neuronal Hyperexcitability and β-Alanine

7.2. Amyloid-β (Aβ) and Tau Protein Aggregation and β-Alanine

7.3. Neuroinflammation and β-Alanine

7.4. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and β-Alanine

7.5. Metal Dyshomeostasis and β-Alanine

7.6. Taurine’s Connection to the Pathogenesis of AD and β-Alanine

7.6.1. Neuronal Hyperexcitability and Taurine

7.6.2. Aβ and Tau Protein Aggregation and Taurine

7.6.3. Neuroinflammation and Taurine

7.6.4. ROS and Taurine

7.6.5. Metal Dyshomeostasis and Taurine

7.7. Comparison of β-Alanine to Other Amino Acids and Multimodal Approaches in AD

7.8. Druggability of β-Alanine

8. Limitations

8.1. Dose Dependence

8.2. Safety

8.3. BBB Saturation

8.4. Translational Feasibility

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chang, F.; Tejal, P.; Schulz, M.E. The “Rising Tide” of dementia in Canada: What does it mean for pharmacists and the people they care for? Can. Pharm. J. 2015, 148, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheltens, P.; Stropper, B.D.; Kivipelto, M.; Holstege, H.; Chételat, G.; Teunissen, C.E.; Cummings, J.; van der Flier, W.M. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 2021, 397, 1577–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, C.A.; Hardy, J.; Schott, J.M. Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 2018, 25, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiannopoulou, K.G.; Papageorgiou, S.G. Current and future treatments for Alzheimer’s disease. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 2013, 6, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiannopoulou, K.G.; Papageorgiou, S.G. Current and Future Treatments in Alzheimer Disease: An Update. J. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Dis. 2020, 12, 1179573520907397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.-C.; Wang, Y.T.; Ren, J. Basic information about memantine and its treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and other clinical applications. Ibrain 2023, 9, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossberg, G.T. Cholinesterase inhibitors for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: Getting on and Staying on. Curr. Ther. Res. Clin. Exp. 2003, 64, 216–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, J.; Apostolova, L.; Rabinovici, G.D.; Atri, A.; Aisen, P.; Greenberg, S.; Hendrix, S.; Selkoe, D.; Weiner, M.; Petersen, R.C.; et al. Lecanemab: Appropriate Use Recommendations. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2023, 10, 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayaprakash, N.; Elumalai, K. Translational Medicine in Alzheimer’s Disease: The Journey of Donanemab From Discovery to Clinical Application. Chronic Dis. Transl. Med. 2025, 11, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, A.; Rasool, A.; Shaheryar, M.; Sarfraz, A.; Sarfraz, Z.; Robles-Velasco, K.; Cherrez-Ojeda, I. Donanemab for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials. Healthcare 2023, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiedje, K.E.; Stevens, K.; Barnes, S.; Weaver, D.F. β-Alanine as a small molecule neurotransmitter. Neurochem. Int. 2010, 57, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komura, J.; Tamai, I.; Senmaru, M.; Terakaki, T.; Sai, Y.; Tsuji, A. Brain-to-blood active transport of β-alanine across the blood-brain barrier. FEBS Lett. 1997, 400, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, E.G.; Aburto, M.R.; Clarke, G.; Cryan, J.F.; O’Driscoll, C.M. The blood-brain barrier in aging and neurodegeneration. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 2659–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitzemann, R.J.; Loh, H.H. A comparison of GABA and beta-alanine transport and GABA membrane binding in the rat brain. J. Neurochem. 1978, 30, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostfeld, I.; Ben-Zeev, T.; Zamir, A.; Levi, C.; Gepner, Y.; Springer, S.; Hoffman, J.R. Role of β-Alanine Supplementation on Cognitive Function, Mood, and Physical Function in Older Adults; Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, T.L.; Hansen, S.; Berry, K.; Mok, C.; Lesk, D. Free amino acids and related compounds in biopsies of human brain. J. Neurochem. 1971, 18, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solis, M.Y.; Cooper, S.; Hobson, R.M.; Artioli, G.G.; Otaduy, M.C.; Roschel, H.; Robertson, J.; Martin, D.; Painelli, V.S.; Harris, R.C.; et al. Effects of beta-alanine supplementation on brain homocarnosine/carnosine signal and cognitive function: An exploratory study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komura, J.; Tamai, I.; Senmaru, M.; Terasaki, T.; Sai, Y.; Tsuji, A. Sodium and chloride ion-dependent transport of beta-alanine across the blood-brain barrier. J. Neurochem. 1996, 67, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesak, O.; Vostalova, J.; Vidlar, A.; Bastlova, P.; Student, V. Carnosine and Beta-Alanine Supplementation in Human Medicine: Narrative Review and Critical Assessment. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, J.; Charles, J.; Unruh, K.; Giebel, R.; Learmonth, L.; Potter, W. Ergogenic effects of β-alanine and carnosine: Proposed future research to quantify their efficacy. Nutrients 2012, 4, 585–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, W.M.; Rathinasabapathi, B. Expression of bacterial L-aspartate-α-decarboxylase in tobacco increases β-alanine and pantothenate levels and improves thermotolerance. Plant Mol. Biol. 2006, 60, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozaki, S.; Webb, M.E.; Niki, H. An activator for pyruvoyl-dependent l-aspartate α-decarboxylase is conserved in a small group of the γ-proteobacteria including Escherichia coli. Microbiologyopen 2012, 1, 298–310. [Google Scholar]

- Cronan, J.E. Beta-Alanine Synthesis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1980, 141, 1291–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayaishi, O.; Nishizuka, Y.; Tatibana, M.; Takeshita, M.; Kuno, S. Enzymatic Studies on the Metabolism of Beta-Alanine. J. Biol. Chem. 1961, 236, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solana-Manrique, C.; Sanz, F.J.; Martínez-Carrión, G.; Paricio, N. Antioxidant and Neuroprotective Effects of Carnosine: Therapeutic Implications in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnackerz, K.D.; Andersen, G.; Dobritzsch, D.; Piskur, J. Degradation of pyrimidines in Saccharomyces kluyveri: Transamination of β-alanine. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2008, 27, 794–799. [Google Scholar]

- Schnackerz, K.D.; Dobritzsch, D. Amidohydrolases of the reductive pyrimidine catabolic pathway. Purification, characterization, structure, reaction mechanisms and enzyme deficiency. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1784, 431–444. [Google Scholar]

- Culbertson, J.Y.; Kreider, R.B.; Greenwood, M.; Cooke, M. Effects of Beta-alanine on muscle carnosine and exercise performance: A review of the current literature. Nutrients 2010, 2, 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, M.F.; DiNicolantonio, J.J. β-Alanine and orotate as supplements for cardiac protection. Open Heart 2014, 1, e000119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulusma, C.C.; Lamers, W.H.; Broer, S.; van de Graaf, S.F.J. Amino acid metabolism, transport and signalling in the liver revisited. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2022, 201, 115074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G. Important roles of dietary taurine, creatine, carnosine, anserine and 4-hydroxyproline in human nutrition and health. Amino Acids 2020, 52, 329–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thwaites, D.T.; McEwan, G.T.; Hirst, B.H.; Simmons, N.L. H(+)-Coupled alpha-Methylaminoisobutyric Acid Transport in Human Intestinal Caco-2 Cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1995, 1234, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, R.J. Beta-Amino Acid Transport across the Renal Brush-Border Membrane Is Coupled to Both Na and Cl. J. Biol. Chem. 1986, 261, 16060–16066. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jessen, H. Taurine and Beta-Alanine Transport in an Established Human Kidney Cell Line Derived from the Proximal Tubule. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1994, 1194, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chesney, R.W.; Zelikovic, I.; Dabbagh, S.; Friedman, A.; Lippincott, S. Development of β-amino acid transport in the kidney. J. Exp. Zool. 1988, 248, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Perim, P.; Marticorena, F.M.; Ribeiro, F.; Barreto, G.; Gobbi, N.; Kerksick, C.; Dolan, E.; Saunders, B. Can the Skeletal Muscle Carnosine Response to Beta-Alanine Supplementation Be Optimized? Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artioli, G.G.; Gualano, B.; Smith, A.; Stout, J.; Lancha, A.H., Jr. Role of β-alanine supplementation on muscle carnosine and exercise performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2010, 42, 1162–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafra, F.; Aragon, M.C.; Valdivieso, F.; Gimenez, C. Beta-Alanine transport into plasma membrane vesicles derived from rat brain synaptosomes. Neurochem. Res. 1984, 9, 696–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kontro, P. Beta-Alanine uptake by mouse brain slices. Neuroscience 1983, 8, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bakardjiev, A.; Bauer, K. Transport of β-alanine and biosynthesis of carnosine by skeletal muscle cells in primary culture. Eur. J. Biochem. 1994, 225, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.C.; Tallon, M.J.; Dunnett, M.; Boobis, L.; Coakley, J.; Kim, H.J.; Fallowfield, J.L.; Hill, C.A.; Sale, C.; Wise, J.A. The absorption of orally supplied β-alanine and its effect on muscle carnosine synthesis in human vastus lateralis. Amino Acids 2006, 30, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegen, S.; Blancqaert, L.; Everaert, I.; Bex, T.; Taes, Y.; Calders, P.; Achten, E.; Derave, W. Meal and beta-alanine coingestion enhances muscle carnosine loading. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2013, 45, 1478–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihl, A.; Fritzson, P. The catabolism of C14-labeled beta-alanine in the intact rat. J. Biol. Chem. 1955, 215, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blancquaert, L.; Baba, S.P.; Kwiatkowski, S.; Stautemas, J.; Stegen, S.; Barbaresi, S.; Chung, W.; Boakye, A.A.; Hoetker, J.D.; Bhatnagar, A.; et al. Carnosine and anserine homeostasis in skeletal muscle and heart is controlled by β-alanine transamination. J. Physiol. 2016, 594, 4849–4863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Ohyama, T.; Kontani, Y.; Matsuda, K.; Sakata, S.F.; Tamaki, N. Influence of Dietary Protein Levels on beta-Alanine Aminotransferase Expression and Activity in Rats. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2001, 47, 275–282. [Google Scholar]

- Rodionov, R.N.; Jarzebska, N.; Weiss, N.; Lentz, S.R. AGXT2: A promiscuous aminotransferase. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 35, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, G.W.; Rougraff, P.M.; Davis, E.J.; Harris, R.A. Purification and Characterization of Methylmalonate-Semialdehyde Dehydrogenase from Rat Liver. Identity to malonate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 14965–14971. [Google Scholar]

- He, W.; Li, Q.; Li, X. Acetyl-CoA regulates lipid metabolism and histone acetylation modification in cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2023, 1878, 188837. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wilson, K.; Hess, J.; Zhang, G.; Brunengraber, H.; Tochtrop, G. Metabolism of Beta-Alanine in Rat Liver: Degradation to Acetyl-CoA and Carboxylation to 2-(aminomethyl)-malonate. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 655.3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robitaille, Y.; Kemball, K.; Sherwin, A.L. Beta-Alanine Uptake Is Upregulated in FeCl3-Induced Cortical Scars. J. Neurol. Sci. 1995, 134, 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- Schon, F.; Kelly, J.S. Selective uptake of (3H)beta-alanine by glia: Association with glial uptake system for GABA. Brain Res. 1975, 86, 243–257. [Google Scholar]

- Iversen, L.L.; Johnston, G.A. GABA uptake in rat central nervous system: Comparison of uptake in slices and homogenates and the effects of some inhibitors. J. Neurochem. 1971, 18, 1939–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roseth, S.; Fonnum, F. A Study of the Uptake of Glutamate, Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA), Glycine and Beta-Alanine in Synaptic Brain Vesicles from Fish and Avians. Neurosci. Lett. 1995, 183, 62–66. [Google Scholar]

- Robitaille, Y.; Sherwin, A. High Affinity (3H)beta-Alanine Uptake by Scar Margins of Ferric Chloride-Induced Epileptogenic Foci in Rat Isocortex. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1984, 43, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jukić, I.; Kolobarić, N.; Stupin, A.; Matić, A.; Kozina, N.; Mihaljević, Z.; Mihalj, M.; Šušnjara, P.; Stupin, M.; Ćurić, Z.B.; et al. Carnosine, small but mighty-prospect of use as functional ingredient for functional food formulation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1037. [Google Scholar]

- Caruso, G.; Pietro, L.D.; Cardaci, V.; Maugeri, S.; Caraci, F. The therapeutic potential of carnosine: Focus on cellular and molecular mechanisms. Curr. Res. Pharmacol. Drug Discov. 2023, 4, 100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, J.R.; Varanoske, A.; Stout, J.R. Effects of β-Alanine Supplementation on Carnosine Elevation and Physiological Performance. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2018, 84, 83–206. [Google Scholar]

- Creighton, J.V.; Gonçalves, L.d.S.; Artioli, G.G.; Tan, D.; Elliott-Sale, K.J.; Turner, M.D.; Doig, C.L.; Sale, C. Physiological Roles of Carnosine in Myocardial Function and Health. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 1914–1929. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, M.; Mousa, A.; Berk, M.; Chia, W.L.; Ukropec, J.; Majid, A.; Ukropcová, B.; de Courten, B. The potential of carnosine in brain-related disorders: A comprehensive review of current evidence. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullan, L.M.; Powel, R.J. Comparison of Binding at Strychnine-Sensitive (Inhibitory Glycine Receptor) and Strychnine-Insensitive (N-Methyl-D-Aspartate Receptor) Glycine Binding Sites. Neurosci. Lett. 1992, 148, 199–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.X.; Lyons-Warren, A.; Thio, L.T. The glycine transport inhibitor sarcosine is an inhibitory glycine receptor agonist. Neuropharmacology 2009, 57, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J.W.; Penney, J.B.; Johnston, M.V.; Young, A.B. Characterization and regional distribution of strychnine-insensitive [3H]glycine binding sites in rat brain by quantitative receptor autoradiography. Neuroscience 1990, 35, 653–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogita, K.; Suzuki, T.; Yoneda, Y. Strychnine-insensitive binding of [3H]glycine to synaptic membranes in rat brain, treated with triton X-100. Neuropharmacology 1989, 28, 1263–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendra, S.; Lynch, J.W.; Pierce, K.D.; French, C.R.; Barry, P.H.; Schofield, P.R. Mutation of an Arginine Residue in the Human Glycine Receptor Transforms P-Alanine and Taurine from Agonists into Competitive Antagonists. Neuron 1995, 14, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendra, S.; Lynch, J.W.; Schofield, P.R. The glycine receptor. Pharmacol. Ther. 1997, 73, 121–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, C.; Banas, C.; Gomora, P.; Komisaruk, B.R. Prevention of the convulsant and hyperalgesic action of strychine by intrathecal glycine and related amino acids. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1988, 29, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmieden, V.; Kuhse, J.; Betz, H. Mutation of Glycine Receptor Subunit Creates Beta-Alanine Receptor Responsive to GABA. Science 1993, 262, 256–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, N.; Warren, R.; Dykes, R.W. The effects of strychnine on neurons in cat somatosensory cortex and its interaction with the inhibitory amino acids, glycine, taurine and β-alanine. Neuroscience 1988, 26, 745–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choquet, D.; Korn, H. Does β-alanine activate more than one chloride channel associated receptor? Neurosci. Lett. 1988, 84, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehm, S.; Harvey, R.J.; von Holst, A.; Rohrer, H.; Betz, H. Glycine Receptors in Cultured Chick Sympathetic Neurons Are Excitatory and Trigger Neurotransmitter Release. J. Physiol. 1997, 504, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishtal, O.A.; Osipchuk, Y.; Vrublevsky, S.V. Properties of glycine-activated conductances in rat brain neurones. Neurosci. Lett. 1988, 84, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFeudis, F.V.; Muñoz, L.M.O.; Vidal, M.A.; Corrochano, G.; del Alamo, M.S. High-affinity binding of β-alanine to cerebral synaptosomes might involve glycine receptors. Experientia 1978, 34, 1169–1170. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.S.; Gibb, T.T.; Farb, D.H. Dual activation of GABAA and glycine receptors by β-alanine: Inverse modulation by progesterone and 5α-pregnan-3α-ol-20-one. Eur. J. Pharmacol. Mol. Pharmacol. 1993, 246, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, M.; Gähwiler, B.H.; Gerber, U. Beta-Alanine and taurine as endogenous agonists at glycine receptors in rat hippocampus in vitro. J. Physiol. 2002, 539, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laube, B.; Langosch, D.; Betz, H.; Schmieden, V. Hyperekplexia mutations of the glycine receptor unmask the inhibitory subsite for β-amino-acids. Neuroreport 1995, 6, 897–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raikwar, S.; Jain, S.K. Recent trends of theranostic applications of nanoparticles in neurodegenerative disorders. In Nanomedical Drug Delivery for Neurodegenerative Diseases, 1st ed.; Yadav, A.K., Shukla, R., Flora, S., Eds.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Enz, R. GABA(C) receptors: A molecular view. Biol. Chem. 2001, 382, 1111–1122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shin, D.J.; Germann, A.L.; Covey, D.F.; Steinbach, J.H.; Akk, G. Analysis of GABAA Receptor Activation by Combinations of Agonists Acting at the Same or Distinct Binding Sites. Mol. Pharmacol. 2019, 95, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.V.; Sahara, Y.; Dzubay, J.A.; Westbrook, G.L. Defining Affinity with the GABA A Receptor. J. Neurosci. 1998, 18, 8590–8604. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Torres, A.; Miledi, R. Expression of Functional Receptors by the Human-Aminobutyric Acid A Gamma 2 Subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 3220–3223. [Google Scholar]

- Chesnoy-Marchais, D. Persistent GABAA/C responses to gabazine, taurine and beta-alanine in rat hypoglossal motoneurons. Neuroscience 2016, 330, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Calvo, D.J.; Miledi, R. Activation of GABA ρ1 receptors by glycine and β-alanine. Neuroreport 1995, 6, 118–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Horikoshi, T.; Asanuma, A.; Yanagisawa, K.; Anzai, K.; Goto, S. Taurine and β-alanine act on both GABA and glycine receptors in Xenopus oocyte injected with mouse brain messenger RNA. Brain Res. 1988, 464, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Orensanz, L.M.; Barrio, L.C. β-Alanine Behaves as γ-Aminobutyric Acid at Xenopus Oocytes Expressing γ-Aminobutyric Acid Receptors. In Neurochemistry, 1st ed.; Teelken, A., Korf, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997; pp. 1123–1129. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D.A.; Scholfield, C.N. Depolarization of neurones in the isolated olfactory cortex of the guinea-pig by y-aminobutyric acid. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1979, 65, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.A.; Galvan, M. Responses of the guinea-pig isolated olfactory cortex slice to y-aminobutyric acid recorded with extracellular electrodes. Br. J. Pharamacol. 1979, 65, 347–353. [Google Scholar]

- Brecha, N.C.; Weigmann, C. Expression of GAT-1, a high-affinity gamma-aminobutyric acid plasma membrane transporter in the rat retina. J. Comp. Neurol. 1994, 345, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckstein-Ludwig, U.; Fei, J.; Schwarz, W. Inhibition of uptake, steady-state currents, and transient charge movements generated by the neuronal GABA transporter by various anticonvulsant drugs. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999, 128, 92–102. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Kfir, E.; Lee, W.; Eskandari, S.; Nelson, N. Zinc Inhibition Of gamma-aminobutyric Acid Transporter 4 (GAT4) Reveals a Link between Excitatory and Inhibitory Neurotransmission. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 6154–6159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jin, X.T.; Galvan, A.; Wichmann, T.; Smith, Y. Localization and function of GABA transporters GAT-1 and GAT-3 in the basal ganglia. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2011, 5, 11339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.R.; Lopez-Corcueral, B.; Mandiyan, S.; Nelson, H.; Nelson, N. Molecular Characterization of Four Pharmacologically Distinct Alpha-Aminobutyric Acid Transporters in Mouse Brain. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 2106–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, S.; Nelson, H.; Tamura, A.; Nelson, N. Short External Loops as Potential Substrate Binding Site Of-Aminobutyric Acid Transporters. J. Bio Chem. 1995, 270, 28712–28715. [Google Scholar]

- Borden, L.A. GABA transporter heterogeneity: Pharmacology and cellular localization. Neurochem. Int. 1996, 29, 335–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werman, R. Criteria for identification of a central nervous system transmitter. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1966, 18, 745–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, M.A.; Bassi, C.; Saunders, M.E.; Nechanitzky, R.; Morgado-Palacin, I.; Zheng, C.; Mak, T.W. Beyond neurotransmission: Acetylcholine in immunity and inflammation. J. Intern. Med. 2020, 287, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowery, N.G.; Smart, T.G. GABA and glycine as neurotransmitters: A brief history. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 147, S109–S119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meldrum, B.S. Glutamate and Glutamine in the Brain Glutamate as a Neurotransmitter in the Brain: Review of Physiology and Pathology. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 1007S–1015S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Rio, R.M.; Muñoz, L.M.O.; DeFeudis, F.V. Contents of Beta-Alanine and Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid in Regions of Rat CNS. Exp. Brain Res. 1977, 28, 225–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostfeld, I.; Hoffman, J.R. The Effect of β-Alanine Supplementation on Performance, Cognitive Function and Resiliency in Soldiers. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juge, N.; Omote, H.; Moriyama, Y. Vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT) transports β-alanine. J. Neurochem. 2013, 127, 482–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, M.; Jacobson, I. Beta-Alanine, a Possible Neurotransmitter in the Visual System? J. Neurochem. 1981, 37, 1353–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, M.; Corazzi, L. Release of Endogenous Amino Acids from Superior Colliculus of the Rabbit: In Vitro Studies After Retinal Ablation. J. Neurochem. 1983, 40, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, D.R.; Watkins, J.C. The excitation and depression of spinal neurones by structurally related amino acids. J. Neurochem. 1960, 6, 117–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.Y.K.; Wainman, D.; Weaver, D.F. N-, Alpha-, and Beta-Substituted 3-Aminopropionic acids: Design, syntheses and antiseizure activities. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2003, 11, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, J.L.; Nicoll, R.A.; Padjenj, A. Studies on Convulsants in the Isolated Frog Spinal Cord. I. antagonism of amino acid responses. J. Physiol. 1975, 245, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breckenridge, R.J.; Nicholson, S.H.; Nicol, A.J.; Suckling, C.J.; Leigh, B.; Iversen, L. Inhibition of neuronal GABA uptake and glial β-alanine uptake by synthetic GABA analogues. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1981, 30, 3045–3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gemelli, T.; Binkowski de Andrade, R.; Rojas, D.B.; Zanatta, A.; Schirmbeck, G.H.; Funchal, C.; Wajner, M.; Dutra-Filho, C.S.; Wannmacher, C.M.D. Chronic Exposure to β-Alanine Generates Oxidative Stress and Alters Energy Metabolism in Cerebral Cortex and Cerebellum of Wistar Rats. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 5101–5110. [Google Scholar]

- Toggenburger, G.; Felix, D.; Cuénod, M.; Henke, H. In Vitro Release of Endogenous β- Alanine, GABA, and Glutamate, and Electrophysiological Effect of β-Alanine in Pigeon Optic Tectum. J. Neurochem. 1982, 39, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- DeFeudis, F.V.; Martin del Rio, R. Is β-alanine an inhibitory neurotransmitter? Gen. Pharmacol. 1977, 8, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostfeld, I.; Zamir, A.; Ben-Zeev, T.; Levi, C.; Gepner, Y.; Peled, D.; Barazany, D.; Spinger, S.; Hoffman, J.R. β-Alanine supplementation improves fractional anisotropy scores in the hippocampus and amygdala in 60–80-year-old men and women. Exp. Gerontol. 2024, 194, 112513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossu da Silveira, D.F.; Gomes, P.S.C.; Meirelles, C.M. Effects of beta-alanine supplementation on cognitive function: A systematic review. Noteb. Educ. Dev. 2024, 16, e6012. [Google Scholar]

- Stout, J.R.; Graves, B.S.; Smith, A.E.; Hartman, M.J.; Cramer, J.T.; Beck, T.W.; Harris, R.C. The effect of beta-alanine supplementation on neuromuscular fatigue in elderly (55–92 Years): A double-blind randomized study. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2008, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, W.P.; Stout, J.R.; Emerson, N.S.; Scanlon, T.C.; Warren, A.M.; Wells, A.J.; Gonzalez, A.M.; Mangine, G.T.; Robinson, E.H., 4th; Fragala, M.S.; et al. Oral nutritional supplement fortified with beta-alanine improves physical working capacity in older adults: A randomized, placebo-controlled study. Exp. Gerontol. 2013, 48, 933–939. [Google Scholar]

- del Favero, S.; Roschel, H.; Solis, M.Y.; Hayashi, A.P.; Artioli, G.G.; Otaduy, M.C.; Benatti, F.B.; Harris, R.C.; Wise, J.A.; Leite, C.C.; et al. Beta-alanine (CarnosynTM) supplementation in elderly subjects (60–80 years): Effects on muscle carnosine content and physical capacity. Amino Acids 2012, 43, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hill, C.A.; Harris, R.C.; Kim, H.J.; Harris, B.D.; Sale, C.; Boobis, L.H.; Kim, C.K.; Wise, J.A. Influence of β-alanine supplementation on skeletal muscle carnosine concentrations and high intensity cycling capacity. Amino Acids 2007, 32, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baguet, A.; Bourgois, J.; Vanhee, L.; Achten, E.; Derave, W. Important role of muscle carnosine in rowing performance. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010, 109, 1096–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hata, J.; Ohara, T.; Katakura, Y.; Shimizu, K.; Yamashita, S.; Yoshida, D.; Honda, T.; Hirakawa, Y.; Shibata, M.; Sakata, S.; et al. Association between Serum β-Alanine and Risk of Dementia. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 188, 1637–1645. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boldyrev, A.A.; Aldini, G.; Derave, W. Physiology and pathophysiology of carnosine. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 1803–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraniuk, J.N.; El-Amin, S.; Corey, R.; Rayhan, R.; Timbol, C. Carnosine treatment for gulf war illness: A randomized controlled trial. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2013, 5, 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Chengappa, K.N.R.; Turkin, S.R.; DeSanti, S.; Bowie, C.R.; Brar, J.S.; Schlicht, P.J.; Murphy, S.L.; Hetrick, M.L.; Bilder, R.; Fleet, D. A preliminary, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of l-carnosine to improve cognition in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2012, 142, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorova, T.N.; Belyaev, M.S.; Trunova, O.A.; Gnezditsky, V.V.; Maximova, M.Y.; Boldyrev, A.A. Neuropeptide carnosine increases stability of lipoproteins and red blood cells as well as efficiency of immune competent system in patients with chronic discirculatory encephalopathy. Biochem. Mosc. Suppl. Ser. 2009, 3, 62–65. [Google Scholar]

- Targa Dias Anastacio, H.; Matosin, N.; Ooi, L. Neuronal hyperexcitability in Alzheimer’s disease: What are the drivers behind this aberrant phenotype? Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandis, D.; Scarmeas, N. Seizures in Alzheimer Disease: Clinical and Epidemiological Data. Epilepsy Curr. 2012, 12, 184–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutula, T.; Cascino, G.; Cavazos, J.; Parada, I.; Ramirez, L. Mossy fiber synaptic reorganization in the epileptic human temporal lobe. Ann. Neurol. 1989, 26, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutula, T.; He, X.X.; Cavazos, J.; Scott, G. Synaptic Reorganization in the Hippocampus Induced by Abnormal Functional Activity. Science 1988, 239, 1147–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, E.F.; Shao, L.R. Mossy fiber sprouting and recurrent excitation: Direct electrophysiologic evidence and potential implications. Epilepsy Curr. 2004, 4, 184–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, J.W.; Lothman, E.W. Dormancy of Inhibitory Interneurons in a Model of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Science 1993, 259, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lothman, E.W.; Bertram, E.H.; Kapur, J.; Stringer, J.L. Recurrent spontaneous hippocampal seizures in the rat as a chronic sequela to limbic status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 1990, 6, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloviter, R.S. Decreased Hippocampal Inhibition and a Selective Loss of Interneurons in Experimental Epilepsy. Science 1987, 235, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloviter, R.S. Permanently Altered Hippocampal Structure, Excitability, and Inhibition After Experimental Status Epilepticus in the Rat: The “Dormant Basket Cell” Hypothesis and Its Possible Relevance to Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Hippocampus 1991, 1, 41–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, L.; Aitken, P.G.; Friedman, A.; Somjen, G.G. An NMDA-mediated component of excitatory synaptic input to dentate granule cells in ‘epileptic’ human hippocampus studied in vitro. Brain Res. 1990, 515, 319–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mody, I.; Stanton, P.K.; Heinemann, U. Activation of N-Methyl-D-Aspartate Receptors Parallels Changes in Cellular and Synaptic Properties of Dentate Gyrus Granule Cells After Kindling. J. Neurophysiol. 1988, 59, 1033–1054. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Geddes, J.W.; Cahan, L.D.; Cooper, S.M.; Kim, R.C.; Choi, B.H.; Cotman, C.W. Altered distribution of excitatory amino acid receptors in temporal lobe epilepsy. Exp. Neurol. 1990, 108, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingledine, R.; McBain, C.J.; McNamara, J.O. Excitatory amino acid receptors in epilepsy. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1990, 11, 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker-Haliski, M.; White, S.H. Glutamatergic mechanisms associated with seizures and epilepsy. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2015, 5, a022863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartzkroin, P.A.; Stafstrom, C.E. Effects of EGTA on the Calcium-Activated Afterhyperpolarization in Hippocampal CA3 Pyramidal Cells. Science 1980, 210, 1125–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartzkroin, P.A.; Wyler, A.R. Mechanisms underlying epileptiform burst discharge. Ann. Neurol. 1980, 7, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blauwblomme, T.; Jiruska, P.; Huberfeld, G. Mechanisms of Ictogenesis. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2014, 114, 155–185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, E.M.; Coulter, D.A. Mechanisms of epileptogenesis: A convergence on neural circuit dysfunction. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soda, T.; Brunetti, V.; Berra-Romani, R.; Moccia, F. The Emerging Role of N-Methyl-D-Aspartate (NMDA) Receptors in the Cardiovascular System: Physiological Implications, Pathological Consequences, and Therapeutic Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3914. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, F.I.F.; Aragão, M.G.B.; Bezerra, M.M.; Chaves, H.V. GABAergic transmission and modulation of anxiety: A review on molecular aspects. Braz. J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 6, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.; Risley, E.A.; Totaro, J.A. Interaction of taurine and β-alanine with central nervous system neurotransmitter receptors. Life Sci. 1980, 26, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seebach, D.; Matthews, J.L. Beta-Peptides: A Surprise at Every Turn. Chem. Commun. 1997, 1, 2015–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, V.C.; Heyding, R.A.; Weaver, D.F. The “promiscuous drug concept” with applications to Alzheimer’s disease. FEBS Lett. 2005, 579, 1338–1342. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, J.E.; Hipkiss, A.R.; Himsworth, D.T.; Romero, I.A.; Abbott, J.N. Toxic effects of β-amyloid(25–35) on immortalised rat brain endothelial cell: Protection by carnosine, homocarnosine and β-alanine. Neurosci. Lett. 1998, 242, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, B.; Sun, M.; Yang, H. Microglia in the Neuroinflammatory Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Therapeutic Targets. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 856376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobue, A.; Komine, O.; Yamanaka, K. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: Microglial signature and their relevance to disease. Inflamm. Regen. 2023, 43, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, J.; Ma, H.; Yang, Y.; Liao, Y.; Lin, C.; Zheng, J.; Yu, M.; Lan, J. Microglia in Alzheimer’s disease: Pathogenesis, mechanisms, and therapeutic potentials. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1201982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, F.; Edison, P. Neuroinflammation and microglial activation in Alzheimer disease: Where do we go from here? Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zong, S.; Cui, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, S.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Z. The effects of microglia-associated neuroinflammation on Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1117172. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, D. Astrocytic and microglial cells as the modulators of neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroinflam. 2022, 19, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.Y.; Tan, M.-S.; Yu, J.-T.; Tan, L. Role of pro-inflammatory cytokines released from microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Transl. Med. 2015, 3, 136. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, A.; Phillips, E.; Zheng, R.; Biju, M.; Kuruvilla, T. Evidence for neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Prog. Neurol. Psychiatry 2016, 20, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, H.; Liang, J.; Huang, J.; Chen, N. Exercise suppresses neuroinflammation for alleviating Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroinflam. 2023, 20, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brod, S.A. Anti-Inflammatory Agents: An Approach to Prevent Cognitive Decline in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2022, 85, 457–472. [Google Scholar]

- Haage, V.; De Jager, P.L. Neuroimmune contributions to Alzheimer’s disease: A focus on human data. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 3164–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorfi, M.; Maaser-Hecker, A.; Tanzi, R.E. The neuroimmune axis of Alzheimer’s disease. Genome Med. 2023, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Huang, H.; Zhao, L. PAMPs and DAMPs as the Bridge Between Periodontitis and Atherosclerosis: The Potential Therapeutic Targets. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 856118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Jiang, L. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015, 11, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feijó, G.; Jantsch, J.; Correia, L.L.; Eller, S.; Furtado-Filho, O.V.; Giovenardi, M.; Porawski, M.; Braganhol, E.; Guedes, R.P. Neuroinflammatory responses following zinc or branched-chain amino acids supplementation in obese rats. Metab. Brain Dis. 2022, 37, 1875–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, V.E.; Boyd, A.; Zhao, J.-W.; Yuen, T.J.; Ruckh, J.M.; Shadrach, J.L.; ven Wijngaarden, P.; Wagers, A.J.; Williams, A.; Franklin, R.J.M.; et al. M2 microglia and macrophages drive oligodendrocyte differentiation during CNS remyelination. Nat. Neurosci. 2013, 16, 1211–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Baydyuk, M.; Huang, J.K. Impact of amino acids on microglial activation and CNS remyelination. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2022, 66, 102287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Y.; Liu, X.; Xu, S.; Wang, P. Reposition: Focalizing β-Alanine Metabolism and the Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Its Metabolite Based on Multi-Omics Datasets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10252. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Zhong, Y.; Ouyang, X.; Wang, C.; Yin, L.; Huang, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Xie, J.; Huang, P.; et al. Effects of β-alanine on intestinal development and immune performance of weaned piglets. Anim. Nutr. 2023, 12, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.-Y.; Moon, H.-W.; Kim, J.-S.; Kim, H.-Y. Effects of 4 Weeks of Beta-Alanine Intake on Inflammatory Cytokines after 10 km Long Distance Running Exercise. Exerc. Sci. 2022, 31, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcu, I.; Oancea, B.; Chicomban, M.; Simion, G.; Simon, S.; Tiuca, C.I.N.; Ordean, M.N.; Petrovici, A.G.; Șeușan, N.A.N.; Hăisan, P.L.; et al. Effect of 8-Week β-Alanine Supplementation on CRP, IL-6, Body Composition, and Bio-Motor Abilities in Elite Male Basketball Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, P.D.; Huang, B.-W.; Tsuji, Y. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis and redox regulation in cellular signaling. Cell. Signal. 2012, 24, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, S.; Guillemin, G.J.; Abiramasundari, R.S.; Essa, M.M.; Akbar, M.; Akbar, M.D. The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, and Huntington’s Disease: A Mini Review. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2016, 2016, 8590578. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, S.; Puli, L.; Patil, C.R. Role of reactive oxygen species in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Drug Discov. Today 2021, 26, 794–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, W.; Ijaz, B.; Shabbiri, K.; Ahmed, F.; Rehman, S. Oxidative toxicity in diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease: Mechanisms behind ROS/ RNS generation. J. Biomed. Sci. 2017, 24, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massaad, C.A. Neuronal and Vascular Oxidative Stress in Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2011, 9, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Houldsworth, A. Role of oxidative stress in neurodegenerative disorders: A review of reactive oxygen species and prevention by antioxidants. Brain Commun. 2024, 6, fcad356. [Google Scholar]

- Ionescu-Tucker, A.; Cotman, C.W. Emerging roles of oxidative stress in brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2021, 107, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Luo, F. The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Alzheimer’s Disease: From Mechanism to Biomaterials Therapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 13, e2304373. [Google Scholar]

- Tamagno, E.; Guglielmotto, M.; Vasciaveo, V.; Tabaton, M. Oxidative Stress and Beta Amyloid in Alzheimer’s Disease. Which Comes First: The Chicken or the Egg? Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheignon, C.; Tomas, M.; Bonnefont-Rousselot, D.; Faller, P.; Hureau, C.; Collin, F. Oxidative stress and the amyloid beta peptide in Alzheimer’s disease. Redox Biol. 2018, 14, 450–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque, M.M.; Murale, D.P.; Kim, Y.K.; Lee, J.-S. Crosstalk between Oxidative Stress and Tauopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, C.; Kim, S.R. Linking Oxidative Stress and Proteinopathy in Alzheimer’s Disease. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.G.; Mandal, P.K.; Maroon, J.C. Oxidative Stress Occurs Prior to Amyloid Aβ Plaque Formation and Tau Phosphorylation in Alzheimer’s Disease: Role of Glutathione and Metal Ions. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2023, 14, 2944–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firdous, S.M.; Khan, S.A.; Maity, A. Oxidative stress-mediated neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2024, 397, 8189–8209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teleanu, D.M.; Niculescu, A.-G.; Lungu, I.I.; Radu, C.I.; Vladâcenco, O.; Roza, E.; Costăchescu, B.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Teleanu, R.I. An Overview of Oxidative Stress, Neuroinflammation, and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganguly, U.; Kaur, U.; Chakrabarti, S.S.; Sharma, P.; Agrawal, B.K.; Saso, L.; Chakrabarti, S. Oxidative Stress, Neuroinflammation, and NADPH Oxidase: Implications in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2021, 2021, 7086512. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, I.; Jha, S. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Alzheimer’s Disease: Role of Microglia. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2020, 12, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekcetin, C.; Kiray, M.; Ergur, B.U.; Bagriyanik, H.A.; Erbil, G.; Baykara, B.; Camsari, U.M. Carnosine attenuates oxidative stress and apoptosis in transient cerebral ischemia in rats. Acta Biol. Hung. 2009, 60, 137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Caruso, G.; Scalisi, E.M.; Pecoraro, R.; Cardaci, V.; Privitera, A.; Truglio, E.; Capparucci, F.; Jorosova, V.; Salvaggio, A.; Caraci, F.; et al. Effects of carnosine on the embryonic development and TiO2 nanoparticles-induced oxidative stress on Zebrafish. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1148766. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, K.-I.; Sugizaki, T.; Kanda, Y.; Tamura, F.; Niino, T.; Kawahara, M. Preventive effects of carnosine on lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Xu, J.; Cui, D.; Liu, L.; Zhang, S.; Shen, B.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Q. Protective effect of carnosine on hydrogen peroxide–induced oxidative stress in human kidney tubular epithelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 534, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.P.; Garrett, M.R.; Perry, G.; Smith, M.A. Carnosine: A versatile antioxidant and antiglycating agent. Sci. Aging Knowl. Environ. 2005, 2005, pe12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokopieva, V.D.; Yarygina, E.G.; Bokhan, N.A.; Ivanova, S.A. Use of Carnosine for Oxidative Stress Reduction in Different Pathologies. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2016, 2016, 2939087. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gasmi, A.; Mujawdiya, P.K.; Lysiuk, R.; Shanaida, M.; Peana, M.; Piscopo, S.; Beley, N.; Dzyha, S.; Smetanina, K.; Shanaida, V.; et al. The Possible Roles of β-alanine and L-carnosine in Anti-aging. Curr. Med. Chem. 2025, 32, 6–22. [Google Scholar]

- Belviranli, M.; Okudan, N.; Revan, S.; Balci, S.; Gokbel, H. Repeated Supramaximal Exercise-Induced Oxidative Stress: Effect of β-Alanine Plus Creatine Supplementation. Asian J. Sports Med. 2016, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- De França, E.; Lira, F.S.; Ruaro, M.F.; Hirota, V.B. The Antioxidant Effect of Beta-Alanine or Carnosine Supplementation on Exercise-Induced Oxidative Stress: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Revista 2019, 12, 57–77. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Ma, J.; Li, H.; Li, H.; Ma, Y.; Deng, H.; Yang, K. Effect of β-alanine on the athletic performance and blood amino acid metabolism of speed-racing Yili horses. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, e26843. [Google Scholar]

- Billacura, M.P.; Lavilla, C., Jr.; Cripps, M.J.; Hanna, K.; Sale, C.; Turner, M.D. β-alanine scavenging of free radicals protects mitochondrial function and enhances both insulin secretion and glucose uptake in cells under metabolic stress. Adv. Redox Res. 2022, 6, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.E.; Stout, J.R.; Kendall, K.L.; Fukuda, D.H.; Cramer, J.T. Exercise-induced oxidative stress: The effects of β-alanine supplementation in women. Amino Acids 2012, 43, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Ryan, A.E.; Fukuda, D.H.; Stout, J.R.; Kendall, K.L. The influence of β-alanine supplementation on markers of exercise-induced oxidative stress. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 39, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csire, G.; Canabady-Rochelle, L.; Averlant-Petit, M.C.; Selmeczi, K.; Stefan, L. Both metal-chelating and free radical-scavenging synthetic pentapeptides as efficient inhibitors of reactive oxygen species generation. Metallomics 2020, 12, 1220–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Yin, Y.-L.; Liu, X.-Z.; Shen, P.; Zheng, Y.-G.; Lan, X.-R.; Lu, C.-B.; Wang, J.-Z. Current understanding of metal ions in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Transl. Neurodegener. 2020, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.-Q.; Tan, S.-S.; Wu, D.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, T.; Zheng, G. The role of intracellular and extracellular copper compartmentalization in Alzheimer’s disease pathology and its implications for diagnosis and therapy. Front. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1553064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagheri, S.; Squitti, R.; Haertlé, T.; Siotto, M.; Saboury, A.A. Role of Copper in the Onset of Alzheimer’s Disease Compared to Other Metals. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 9, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejaz, H.W.; Wang, W.; Lang, M. Copper Toxicity Links to Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease and Therapeutics Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squitti, R.; Lupoi, D.; Pasqualetti, P.; Forno, G.D.; Vernieri, F.; Chiovenda, P.; Rossi, L.; Cortesi, M.; Cassetta, E.; Rossini, P.M. Elevation of serum copper levels in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 2002, 59, 1153–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Church, S.J.; Patassini, S.; Begley, P.; Waldvogel, H.J.; Curtis, M.A.; Faull, R.L.M.; Unwin, R.D.; Cooper, G.J.S. Evidence for widespread, severe brain copper deficiency in Alzheimer’s dementia. Metallomics 2017, 9, 1106–1119. [Google Scholar]

- Rivers-Auty, J.; Tapia, V.S.; White, C.S.; Daniels, M.J.D.; Drinkall, S.; Kennedy, P.T.; Spence, H.G.; Yu, S.; Green, J.P.; Hoyle, C.; et al. Zinc Status Alters Alzheimer’s Disease Progression through NLRP3-Dependent Inflammation. J. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 3025–3038. [Google Scholar]

- Watt, N.T.; Whitehouse, I.J.; Hooper, N.M. The Role of Zinc in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2010, 2011, 971021. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Z.; Wu, H.; Zhao, J. Multifunctional roles of zinc in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotoxicology 2020, 80, 112–123. [Google Scholar]

- Alies, B.; Conte-Daban, A.; Sayen, S.; Collin, F.; Kieffer, I.; Guillon, E.; Faller, P.; Hureau, C. Zinc(II) Binding Site to the Amyloid-β Peptide: Insights from Spectroscopic Studies with a Wide Series of Modified Peptides. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 10499–10509. [Google Scholar]

- Curtain, C.C.; Ali, F.; Volitakis, I.; Cherny, R.A.; Norton, R.S.; Beyreuther, K.; Barrow, C.J.; Masters, C.L.; Bush, A.I.; Barnham, K.J. Alzheimer’s Disease Amyloid-β Binds Copper and Zinc to Generate an Allosterically Ordered Membrane-penetrating Structure Containing Superoxide Dismutase-like Subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 20466–20473. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei-Ghaleh, N.; Giller, K.; Becker, S.; Zweckstetter, M. Effect of Zinc Binding on β-Amyloid Structure and Dynamics: Implications for Aβ Aggregation. Biophys. J. 2011, 101, 1202–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, G.; Kanzer, S.H.; Zimmerman, A.E.; Heckman, S.M.; Newsome, D. Sub-clinical Zinc Deficiency Found in Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2009, 5, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, C.; Masciopinto, F.; Silvestri, E.; Viscovo, A.D.; Lattanzio, R.; Sorda, R.L.; Ciavardelli, D.; Goglia, F.; Piantelli, M.; Canzoniero, L.M.T.; et al. Dietary zinc supplementation of 3xTg-AD mice increases BDNF levels and prevents cognitive deficits as well as mitochondrial dysfunction. Cell Death Dis. 2010, 1, e91. [Google Scholar]

- Religa, D.; Strozyk, D.; Cherny, R.A.; Volitakis, I.; Haroutunian, V.; Winblad, B.; Naslund, J.; Bush, A.I. Elevated cortical zinc in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2006, 67, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayton, S.; Portbury, S.; Kalinowski, P.; Diouf, I.; Agarwal, P.; Schneider, J.A.; Morris, M.C.; Bush, A.I. Brain iron burden is associated with accelerated cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2020, 16, e044124. [Google Scholar]

- Bartzokis, G.; Sultzer, D.; Cummings, J.; Holt, L.E.; Hance, D.B.; Henderson, V.W.; Mintz, J. In vivo evaluation of brain iron in Alzheimer disease using magnetic resonance imaging. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2000, 57, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Sun, J.; Cong, S. Levels of iron and iron-related proteins in Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2023, 80, 127304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gao, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Hu, W.; Jin, W.; Zhou, C.; Yuan, H.; Li, J.; Lin, Z.; Lin, W. Role of iron in brain development, aging, and neurodegenerative diseases. Ann. Med. 2025, 57, 2472871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, J.; Shen, Y.; Li, H.; Rausch, W.-D.; Huang, X. Iron Dyshomeostasis and Ferroptosis: A New Alzheimer’s Disease Hypothesis? Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 830569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.; DiGiacomo, P.; Born, D.E.; Georgiadis, M.; Zeineh, M. Iron and Alzheimer’s Disease: From Pathology to Imaging. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 838692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kontoghiorghes, G.J. Advances on chelation and chelator metal complexes in medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolev, N.; Katz, Z.; Ludmer, Z.; Ullmann, A.; Brauner, N.; Goikhman, R. Natural amino acids as potential chelators for soil remediation. Environ. Res. 2020, 183, 109140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, R.H.; Afify, A.S.; Shanab, S.M.; Shalaby, E.A. Chelated amino acids: Biomass sources, preparation, properties, and biological activities. Biomass Convers. Biorefin 2024, 14, 2907–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuajungco, M.P.; Fagét, K.Y.; Huang, X.; Tanzi, R.E.; Bush, A.I. Metal chelation as a potential therapy for Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2000, 920, 292–304. [Google Scholar]

- Pulido, A.; Hulbert, B.; Giese, H.; Kurian, S.; Rozhon, R.; Zambrano, M.; Diaz, O.; Abd, M.; Caputo, M.; Kissel, D.S.; et al. Copper Chelation via beta-alanine extends lifespan in a C. elegans model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Disord. 2023, 10, 100076. [Google Scholar]

- Abate, C.; Aiello, D.; Cordaro, M.; Giuffrè, O.; Naploi, A.; Foti, C. Binding ability of l-carnosine towards Cu2+, Mn2+ and Zn2+ in aqueous solution. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 368, 120772. [Google Scholar]

- Torreggiani, A.; Tamba, M.; Fini, G. Copper(II) complex with L-carnosine as a ligand: The tautomeric change of the imidazole moiety upon complexation. In Spectroscopy of Biological Molecules: New Directions, 1st ed.; Greve, J., Puppels, G.J., Otto, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 71–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara, M.; Tanaka, K.-I.; Kato-Negishi, M. Zinc, Carnosine, and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Nutrients 2018, 10, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.E.; Antholine, W.E. Chelation chemistry of carnosine. Evidence that mixed complexes may occur in vivo. J. Phys. Chem. 1979, 83, 3314–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Aviles, M.; Moreno-Fernandez, J.; Kose, T.; Hider, R.; Latunde-Dada, G.O. Effect of histidine and carnosine on haemoglobin recovery in anaemia induced-kidney damage and iron-loading mouse models. Amino Acids 2025, 57, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Ripps, H.; Shen, W. Review: Taurine: A “very essential” amino acid. Mol. Vis. 2012, 18, 2673–2686. [Google Scholar]

- Marcinkiewicz, J.; Kontny, E. Taurine and inflammatory diseases. Amino Acids 2014, 46, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Ayuso, D.; Pierdomenico, J.D.; Martínez-Vacas, A.; Vidal-Sanz, M.; Picaud, S.; Villegas-Pérez, M. Taurine: A promising nutraceutic in the prevention of retinal degeneration. Neural Regen. Res. 2023, 19, 606–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakaria, M.D.; Azam, S.; Haque, M.E.; Jo, S.-H.; Uddin, M.S.; Kim, I.-S.; Choi, D.-K. Taurine and its analogs in neurological disorders: Focus on therapeutic potential and molecular mechanisms. Redox Biol. 2019, 24, 101223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiee, Z.; García-Serrano, A.M.; Duarte, J.M.N. Taurine Supplementation as a Neuroprotective Strategy upon Brain Dysfunction in Metabolic Syndrome and Diabetes. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-Y.; Prentice, H. Role of taurine in the central nervous system. J. Biomed. Sci. 2010, 17, S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardridge, W.M. Drug transport across the blood–brain barrier. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2012, 32, 959–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Kim, H.V.; Yoon, J.H.; Kang, B.R.; Cho, S.M.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, J.W.; Cho, Y.; Woo, J.; et al. Taurine in drinking water recovers learning and memory in the adult APP/PS1 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 7467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.J.; Lee, H.-J.; Jeong, Y.J.; Nam, K.R.; Kang, K.J.; Han, S.J.; Lee, K.C.; Lee, Y.J.; Choi, J.Y. Evaluation of the neuroprotective effect of taurine in Alzheimer’s disease using functional molecular imaging. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Xia, S.; He, J.; Lu, G.; Xie, Z.; Han, H. Roles of taurine in cognitive function of physiology, pathologies and toxication. Life Sci. 2019, 231, 116584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, N.Y.; Kang, Y.S. Taurine Protects Glutamate Neurotoxicity in Motor Neuron Cells. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 975, 887–895. [Google Scholar]

- L’Amoreaux, W.J.; Marsillo, A.; Idrissi, A.E. Pharmacological characterization of GABAA receptors in taurine-fed mice. J. Biomed. Sci. 2010, 17, S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Yue, M.; Chandra, D.; Keramidas, A.; Goldstein, P.A.; Homanics, G.E.; Harrison, N.L. Taurine Is a Potent Activator of Extrasynaptic GABAA Receptors in the Thalamus. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 106–115. [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa-de la Paz, L.; Zenteno, E.; Gulias-Cañizo, R.; Quiroz-Mercado, H. Taurine and GABA neurotransmitter receptors, a relationship with therapeutic potential? Expert. Rev. Neurother. 2019, 19, 289–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau, M.H.; Olsen, R.W. Taurine acts on a subclass of GABAA receptors in mammalian brain in vitro. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1991, 207, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, C.Y.; Sun, H.S.; Shah, S.M.; Agovic, M.S.; Ho, I.; Friedman, E.; Banerjee, S.P. Direct interaction of taurine with the NMDA glutamate receptor subtype via multiple mechanisms. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2013, 775, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Paula-Lima, A.C.; De Felice, F.G.; Brito-Moreira, J.; Ferreira, S.T. Activation of GABAA receptors by taurine and muscimol blocks the neurotoxicity of β-amyloid in rat hippocampal and cortical neurons. Neuropharmacology 2005, 49, 1140–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.Y.; Sun, H.S.; Shah, S.M.; Agovic, M.S.; Friedman, E.; Banerjee, S.P. Modes of direct modulation by taurine of the glutamate NMDA receptor in rat cortex. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 728, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, L.M.; Solís, J.M. Taurine potentiates presynaptic NMDA receptors in hippocampal Schaffer collateral axons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006, 24, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louzada, P.R.; Lima, A.C.P.; Mendonca-Silva, D.L.; Noël, F.; De Mello, F.G.; Ferreira, S.T. Taurine prevents the neurotoxicity of beta-amyloid and glutamate receptor agonists: Activation of GABA receptors and possible implications for Alzheimer’s disease and other neurological disorders. FASEB J. 2004, 18, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Hossain, M.K.; Lee, H.-L.; Kumar, V.; Shin, S.J.; Kim, B.-H.; Park, H.H.; Son, J.G.; Moon, M.; Kim, H.-R. Taurine suppresses Aβ aggregation and attenuates Alzheimer’s disease pathologies in 5XFAD mice and patient-derived cerebral organoids. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, 191, 118527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Lee, S.; Choi, S.L.; Kim, H.Y.; Baek, S.; Kim, Y. Taurine Directly Binds to Oligomeric Amyloid-β and Recovers Cognitive Deficits in Alzheimer Model Mice. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 975, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abdulkadir, T.S.; Isa, A.S.; Dawud, F.A.; Ayo, J.O.; Mohammed, M.D. Effect of taurine and camel milk on amyloid beta peptide concentration and oxidative stress changes in aluminium chloride-induced Alzheimer’s disease rats. Alzheimers Dement. 2021, 17, e058642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanshahi, M.; Nikmahzar, E.; Gorgani, S. Taurine can decrease phosphorylated tau protein levels in Alzheimer’s model rats’ brains. Kathmandu Univ. Med. J. 2021, 19, 200–204. [Google Scholar]

- Asadi, Z.; Jahanshahi, M.; Vaezi, G.; Hosseini, S.M. Effects of Taurine on Phosphorylated Tau Protein Level in the Hippocampus of Scopolamine-Treated Adult Male Rats. J. Maz. Univ. Med. Sci. 2018, 28, 152–157. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.; Ma, N.; Kawanokuchi, J.; Matsuoka, K.; Oikawa, S.; Kobayashi, H.; Hiraku, Y.; Murata, M. Taurine reduces microglia activation in the brain of aged senescence-accelerated mice by increasing the level of TREM2. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Qu, J.; Li, Q.; Cui, M.; Wang, J.; Zhang, K.; Liu, X.; Feng, H.; Chen, Y. Taurine supplementation reduces neuroinflammation and protects against white matter injury after intracerebral hemorrhage in rats. Amino Acids 2018, 50, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zhu, R.; Jiang, H.; Li, B.; Geng, Q.; Li, Y.; Qi, J. Taurine inhibits KDM3a production and microglia activation in lipopolysaccharide-treated mice and BV-2 cells. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2022, 122, 103759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.P.; Zago, A.M.; Carvalho, F.B.; Germann, L.; Colombo, G.M.; Rahmeier, F.L.; Gutierres, J.M.; Reschke, C.R.; Bagatini, M.D.; Assmann, C.E.; et al. Neuroprotective Effect of Taurine against Cell Death, Glial Changes, and Neuronal Loss in the Cerebellum of Rats Exposed to Chronic-Recurrent Neuroinflammation Induced by LPS. J. Immunol. Res. 2021, 2021, 7497185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Y.; Hou, L.; Sun, F.; Zhang, C.; Lu, X.; Piao, F.; Zhang, D.; Li, H.; Wang, Q. Taurine protects dopaminergic neurons in a mouse Parkinson’s disease model through inhibition of microglial M1 polarization. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Fan, W.; Ma, Z.; Wen, X.; Wang, W.; Wu, Q.; Huang, H. Taurine improves functional and histological outcomes and reduces inflammation in traumatic brain injury. Neuroscience 2014, 266, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chupel, M.U.; Minuzzi, L.G.; Furtado, G.; Santos, M.L.; Hogervorst, E.; Filaire, E.; Teixeira, A.M. Exercise and taurine in inflammation, cognition, and peripheral markers of blood-brain barrier integrity in older women. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 43, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahdat, M.; Hosseini, S.A.; Soltani, F.; Cheraghian, B.; Namjoonia, M. The effects of Taurine supplementation on inflammatory markers and clinical outcomes in patients with traumatic brain injury: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Nutr. J. 2021, 20, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Cheong, S.H. Taurine Have Neuroprotective Activity against Oxidative Damage-Induced HT22 Cell Death through Heme Oxygenase-1 Pathway. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 975, 59–171. [Google Scholar]

- Jong, C.J.; Azuma, J.; Schaffer, S. Mechanism underlying the antioxidant activity of taurine: Prevention of mitochondrial oxidant production. Amino Acids 2012, 42, 2223–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abud, G.F.; De Carvalho, F.G.; Batitucci, G.; Travieso, S.G.; Bueno, C.R., Jr.; Barbosa, F.B., Jr.; Marchini, J.S.; De Freitas, E.C. Taurine as a possible antiaging therapy: A controlled clinical trial on taurine antioxidant activity in women ages 55 to 70. Nutrition 2022, 101, 111706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teles, A.; Guzmán-Villanueva, L.; Hernández-de Dios, M.A.; Corona-Rojas, D.A.; Maldonado-García, M.; Tovar-Ramírez, D. Taurine Enhances Antioxidant Enzyme Activity and Immune Response in Seriola rivoliana Juveniles After Lipopolysaccharide Injection. Fishes 2025, 10, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, V.; Mahdavi, R.; Hajizadeh-Sharafabad, F.; Alizadeh, M. The effects of taurine supplementation on oxidative stress indices and inflammation biomarkers in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2020, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, K.; Jong, C.J.; Takahashi, K.; Schaffer, S.W. Role of ROS Production and Turnover in the Antioxidant Activity of Taurine. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2015, 803, 581–596. [Google Scholar]

- Surai, P.F.; Earle-Payne, K.; Kidd, M.T. Taurine as a Natural Antioxidant: From Direct Antioxidant Effects to Protective Action in Various Toxicological Models. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jong, C.J.; Sandal, P.; Schaffer, S.W. The Role of Taurine in Mitochondria Health: More Than Just an Antioxidant. Molecules 2021, 26, 4913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, X.; Li, S.; Guo, W.; Chen, M.; Yan, X.; Jiang, L.; Piao, F. Taurine normalizes the levels of Se, Cu, Fe in mouse liver and kidney exposed to arsenic subchronically. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 975, 843–853. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, E.C.; Farkas, E.; Nolan, K.B. Interaction of taurine with metal ions. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2000, 483, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tekin, E.; Karakelle, N.A.; Dinçer, S. Effects of taurine on metal cations, transthyretin and LRP-1 in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2023, 79, 127219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.S.; Yoo, I.S.; Shin, K.O.; Chung, K.H. Effects of taurine on cadmium exposure in muscle, gill, and bone tissues of Carassius auratus. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2013, 7, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Qi, Z.; Huang, C.; Lin, D. Taurine Alleviates Ferroptosis-Induced Metabolic Impairments in C2C12 Myoblasts by Stabilizing the Labile Iron Pool and Improving Redox Homeostasis. J. Proteome Res. 2024, 23, 3444–3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenting, L.; Ping, L.; Haitao, J.; Meng, Q.; Xiaofei, R. Therapeutic effect of taurine against aluminum-induced impairment on learning, memory and brain neurotransmitters in rats. Neurol. Sci. 2014, 35, 1579–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Król, E.; Okulicz, M.; Kupsz, J. The Influence of Taurine Supplementation on Serum and Tissular Fe, Zn and Cu Levels in Normal and Diet-Induced Insulin-Resistant Rats. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2020, 198, 592–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oudit, G.Y.; Trivieri, M.F.; Khaper, N.; Husain, T.; Wilson, G.J.; Liu, P.; Sole, M.J.; Backx, P.J. Taurine supplementation reduces oxidative stress and improves cardiovascular function in an iron-overload murine model. Circulation 2004, 109, 1877–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, E.; Hashimoto, K.; Harai, T.; Mori, H. NMDA- and β-Amyloid1–42-Induced Neurotoxicity Is Attenuated in erine Racemase Knock-Out Mice. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 14486–14491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Inoue, R.; Wu, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Yaku, K.; Nakagawa, T.; Satio, T.; Saido, T.C.; Takao, K.; Mori, H. Regional contributions of D-serine to Alzheimer’s disease pathology in male AppNL–G–F/NL–G–F mice. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1211067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billard, J.-M.; Ploux, E.; Largilliere, S.; Corvaisier, S.; Gorisse-Hussonnois, L.; Radzishevsky, I.; Wolosker, H.; Freret, T. Early involvement of D-serine in β-amyloid-dependent pathophysiology. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2025, 82, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birdsall, T.C. 5-Hydroxytryptophan: A clinically-effective serotonin precursor. Altern. Med. Rev. 1998, 109, 325–338. [Google Scholar]

- Noristani, H.N.; Verkhratsky, A.; Rodríguez, J.J. High tryptophan diet reduces CA1 intraneuronal β-amyloid in the triple transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Cell 2012, 11, 810–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, R.M.; Rees, D.D.; Ashton, D.S.; Moncada, S. L-arginine is the physiological precursor for the formation of nitric oxide in endothelium-dependent relaxation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1988, 153, 1251–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Fleete, M.S.; Jing, Y.; Collie, N.D.; Curtis, M.A.; Waldvogel, H.J.; Faull, R.L.M.; Abraham, W.C.; Shang, H. Altered arginine metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease brains. Neurobiol. Aging 2014, 35, 1992–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geravand, S.; Karami, M.; Sahraei, H.; Rahimik, F. Protective effects of L-arginine on Alzheimer’s disease: Modulating hippocampal nitric oxide levels and memory deficits in aluminum chloride-induced rat model. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 958, 176030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atri, A.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Lemming, O.; Wirth, Y.; Pulte, I.; Wilkinson, D. Memantine in patients with Alzheimer’s disease receiving donepezil: New analyses of efficacy and safety for combination therapy. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2013, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolognesi, M.L.; Cavalli, A.; Melchiorre, C. Memoquin: A Multi-Target–Directed Ligand as an Innovative Therapeutic Opportunity for Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2009, 6, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinreb, O.; Amit, T.; Bar-Am, O.; Youdmin, M.B.H. A novel anti-Alzheimer’s disease drug, ladostigil: Neuroprotective, multimodal brain-selective monoamine oxidase and cholinesterase inhibitor. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2011, 100, 191–215. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, L.S.; Geffen, Y.; Rabinowitz, J.; Thomas, R.G.; Schmidt, R.; Ropele, S.; Weinstock, M.; Ladostigil Study Group. Low-dose ladostigil for mild cognitive impairment: A phase 2 placebo-controlled clinical trial. Neurology 2019, 93, e1474–e1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trexler, E.T.; Smith-Ryan, A.E.; Stout, J.R.; Hoffman, J.R.; Wilborn, C.D.; Sale, C.; Kreider, R.B.; Jäger, R.; Earnest, C.P.; Bannock, L.; et al. International society of sports nutrition position stand: Beta-Alanine. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2015, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunder, B.; Franchi, M.; Farias de Oliveira, L.; Silva, V.d.E.; Pires da Silva, R.; Painelli, V.d.S.; Costa, L.A.R.; Sale, C.; Harris, R.C.; Roschel, H.; et al. 24-Week β-alanine ingestion does not affect muscle taurine or clinical blood parameters in healthy males. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Therapeutic Name | Mechanism of Action of Therapeutic | Limitations of Therapeutic | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Memantine | NMDA Receptor Antagonists | Only symptomatic relief | [6] |

| Donepezil, Galantamine, and Rivastigmine | Cholinesterase Inhibitors | [7] | |

| Lecanemab | Binds to amyloid oligomers, protofibrils, and insoluble fibrils | Cerebral microhemorrhages and vasogenic cerebral edema | [8,9,10] |

| Donanemab | Binds to N-terminal pyroglutamate (N3pG) Aβ plaques, thereby reducing the buildup of this misfolded protein |

| Amino Acid | Mechanism | Evidence | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| L-Serine | A precursor for D-serine (NMDA co-agonist). | AD animal models demonstrate neurodegenerative effects in the presence of altered D-serine. | [278,279,280] |

| L-Tryptophan/5-HTP | A precursor to serotonin with receptors found on postsynaptic and presynaptic neurons. | AD animal models supplemented with high tryptophan reduced Aβ density. | [281,282] |

| L-Arginine | A precursor of nitric oxide that diffuses across the cell membrane. | AD animal models demonstrate neuroprotection when supplemented with arginine. | [283,284,285] |

| Intervention | Evidence | Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Memantine and Donepezil | The combination treatment showed a reduction in clinical worsening with reasonable safety and tolerability. | Benefits are small to modest, and this is only symptomatic relief and not disease modification. | [6,7,286] |

| Memoquin | In vitro and in vivo studies suggest this molecule can target multiple receptor sites involved in AD pathogenesis: ACh inhibition, anti-Aβ aggregation, and antioxidant properties. | No clinical data supporting in vitro and in vivo studies. | [287] |

| Ladostigil | Shown to target monoamine oxidaseA and B and cholinesterase inhibitory activities. | Primary endpoints not met in Phase II clinical trials. | [288,289] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wozniczka, C.M.; Weaver, D.F. β-Alanine Is an Unexploited Neurotransmitter in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. NeuroSci 2026, 7, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci7010013

Wozniczka CM, Weaver DF. β-Alanine Is an Unexploited Neurotransmitter in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. NeuroSci. 2026; 7(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci7010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleWozniczka, Cindy M., and Donald F. Weaver. 2026. "β-Alanine Is an Unexploited Neurotransmitter in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease" NeuroSci 7, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci7010013

APA StyleWozniczka, C. M., & Weaver, D. F. (2026). β-Alanine Is an Unexploited Neurotransmitter in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. NeuroSci, 7(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci7010013