Validation and Interpretation of the Persian Version of the Swallowing Disturbance Questionnaire in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Translation of SDQ

2.2.1. Forward Translation

2.2.2. Backward Translation

2.2.3. Comparison and Reconciliation

2.2.4. Expert Panel Review

2.3. Data Collection and Tests

2.3.1. Swallowing Disturbance Questionnaire (SDQ)

2.3.2. Dysphagia in Multiple Sclerosis (DYMUS)

2.3.3. Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29)

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population Characteristics

3.2. Reliability

3.3. Construct Validity

3.4. Convergent Validity and Other Correlations

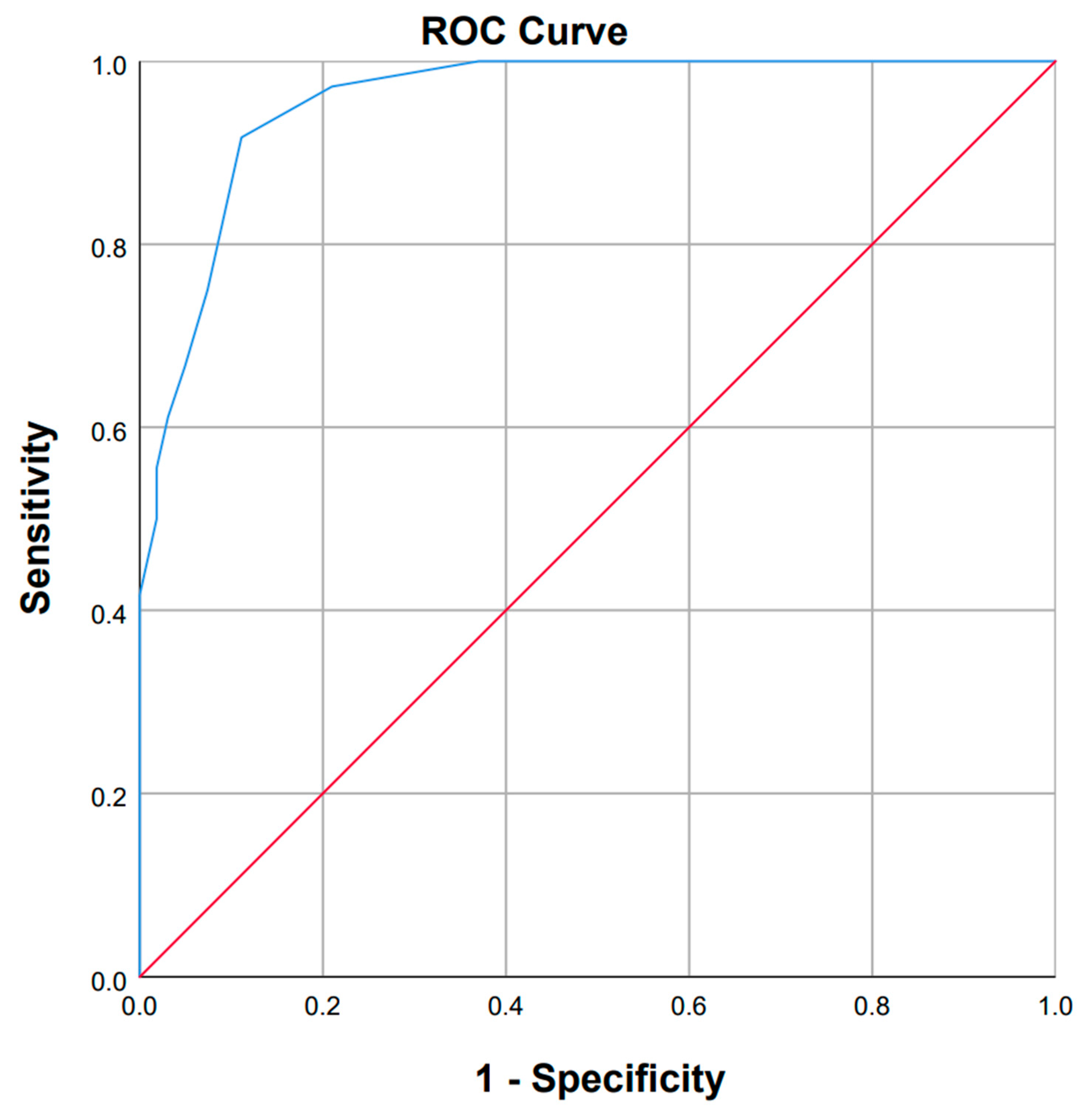

3.5. Interpretability

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lakin, L.; Davis, B.E.; Binns, C.C.; Currie, K.M.; Rensel, M.R. Comprehensive approach to management of multiple sclerosis: Addressing invisible symptoms—A narrative review. Neurol. Ther. 2021, 10, 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.M.F.; Duprat, A.d.C.; Eckley, C.A.; Silva, L.d.; Ferreira, R.B.; Tilbery, C.P. Oropharyngeal dysphagia in patients with multiple sclerosis: Do the disease classification scales reflect dysphagia severity? Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2013, 79, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcagno, P.; Ruoppolo, G.; Grasso, M.; De Vincentiis, M.; Paolucci, S. Dysphagia in multiple sclerosis–prevalence and prognostic factors. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2002, 105, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorjavad, M.; Derakhshandeh, F.; Etemadifar, M.; Soleymani, B.; Minagar, A.; Maghzi, A.-H. Oropharyngeal dysphagia in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2010, 16, 362–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alali, D.; Ballard, K.; Bogaardt, H. The frequency of dysphagia and its impact on adults with multiple sclerosis based on patient-reported questionnaires. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2018, 25, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belafsky, P.C.; Mouadeb, D.A.; Rees, C.J.; Pryor, J.C.; Postma, G.N.; Allen, J.; Leonard, R.J. Validity and reliability of the Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10). Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2008, 117, 919–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.; Ohnishi, H.; Nonaka, M.; Yamauchi, R.; Hozuki, T.; Hayashi, T.; Saitoh, M.; Hisahara, S.; Imai, T.; Shimohama, S. Relationship between dysphagia and depressive states in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2011, 17, 437–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golabbakhsh, M.; Rajaei, A.; Derakhshan, M.; Sadri, S.; Taheri, M.; Adibi, P. Automated acoustic analysis in detection of spontaneous swallows in Parkinson’s disease. Dysphagia 2014, 29, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajaei, A.; Bafrooei, E.B.; Mojiri, F.; Nilforoush, M.H. The occurrence of laryngeal penetration and aspiration in patients with glottal closure insufficiency. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2014, 2014, 587945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.; Kwai Yi Lam, F.; Kwong Lau, K.; Kay Chan, Y.; Yee Ling Kan, E.; Woo, J.; Kee Wong, F.; Ko, A. Simple clinical tests may predict severe oropharyngeal dysphagia in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2007, 22, 640–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamaschi, R.; Crivelli, P.; Rezzani, C.; Patti, F.; Solaro, C.; Rossi, P.; Restivo, D.; Maimone, D.; Romani, A.; Bastianello, S. The DYMUS questionnaire for the assessment of dysphagia in multiple sclerosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2008, 269, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manor, Y.; Giladi, N.; Cohen, A.; Fliss, D.M.; Cohen, J.T. Validation of a swallowing disturbance questionnaire for detecting dysphagia in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2007, 22, 1917–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.J.; Banwell, B.L.; Barkhof, F.; Carroll, W.M.; Coetzee, T.; Comi, G.; Correale, J.; Fazekas, F.; Filippi, M.; Freedman, M.S. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtzke, J.F. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: An expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983, 33, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparaco, M.; Maida, E.; Bile, F.; Vele, R.; Lavorgna, L.; Miele, G.; Bonavita, S. Validation of the swallowing disturbance questionnaire in people with multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2024, 81, 105142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadollahpour, F.; Mehri, A.; Khatoonabadi, A.; Mohammadzaheri, F.; Ebadi, A. Validation of the Persian version of the dysphagia in multiple sclerosis questionnaire for the assessment of dysphagia in multiple sclerosis. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2019, 24, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayatollahi, P.; Nafissi, S.; Eshraghian, M.; Tarazi, A. Cross-cultural adaptation of the multiple sclerosis impact scale (msis-29) for iranian ms patients, evaluation of reliability and validity. Tehran Univ. Med. Sci. J. 2006, 64, 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, I. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; internat. stud. ed., [Nachdr.]; McGraw-Hill Series in Psychology; Tata McGraw-Hill Ed: New Delhi, India, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F.; Rice, J. Little jiffy, mark IV. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1974, 34, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: Pearson New International Edition PDF eBook, 7th ed.; Pearson Higher Ed: Harlow, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jafari, Z.; Shahbodaghi, M.R.; Maroufizadeh, S.; Moghadasi, A.N. Validation of the Persian version of dysphagia in multiple sclerosis questionnaire for the assessment of dysphagia in multiple sclerosis. Iran. J. Neurol. 2018, 17, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.T.; Manor, Y. Swallowing disturbance questionnaire for detecting dysphagia. Laryngoscope 2011, 121, 1383–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manor, Y.; Oestreicher-Kedem, Y.; Gad, A.; Zitser, J.; Faust-Socher, A.; Shpunt, D.; Naor, S.; Inbar, N.; Kestenbaum, M.; Giladi, N. Dysphagia characteristics in Huntington’s disease patients: Insights from the Fiberoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing and the Swallowing Disturbances Questionnaire. Cns Spectr. 2019, 24, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaytsevskaya, S.A.; Lyukmanov, R.K.; Berdnikovich, E.S.; Suponeva, N.A. Dysphagia in neurological disorders. Ann. Clin. Exp. Neurol. 2024, 18, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, K.W.; da Cunha Rodrigues, E.; Rech, R.S.; da Ros Wendland, E.M.; Neves, M.; Hugo, F.N.; Hilgert, J.B. Using voice change as an indicator of dysphagia: A systematic review. Dysphagia 2022, 37, 736–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Ikeda, K.; Usui, H.; Miyamoto, M.; Murata, M. Validation of the Japanese translation of the Swallowing Disturbance Questionnaire in Parkinson’s disease patients. Qual. Life Res. 2012, 21, 1299–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajaei, A.; Azargoon, S.A.; Nilforoush, M.H.; Barzegar Bafrooei, E.; Ashtari, F.; Chitsaz, A. Validation of the Persian translation of the swallowing disturbance questionnaire in Parkinson’s disease patients. Park. Dis. 2014, 2014, 159476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponsoni, A.; Costa, F.P.; Soares, V.N.; Santos, C.G.S.; Mourão, L.F. Sensitivity and specificity of the EAT-10 and SDQ-DP in identifying the risk of dysphagia in Parkinson’s disease. Arq. De Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2024, 82, s00441779055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | PwMS (n = 198) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 36 (30–40) | |

| Gender, n (%) | Female | 171 (86.4) |

| Male | 27 (13.6) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | Single | 51 (25.8) |

| Married | 147 (74.2) | |

| Education years, median (IQR) | 16 (12–16) | |

| Job, n (%) | Not occupied | 108 (54.5) |

| Occupied | 90 (45.5) | |

| MS type, n (%) | RRMS | 181 (91.4) |

| SPMS | 14 (7.1) | |

| PPMS | 3 (1.5) | |

| Age at onset, median (IQR) | 27 (22.9–32) | |

| Disease duration, median (IQR) | 7 (4–10) | |

| EDSS, median (IQR) | 1 (1–2.5) | |

| DMT, n (%) | RTX | 68 (34.3) |

| DMF | 47 (23.7) | |

| IFN | 28 (14.1) | |

| TFN | 28 (14.1) | |

| OCR | 22 (11.1) | |

| Fingolimod | 3 (1.5) | |

| GA | 2 (1) | |

| DYMUS, median (IQR) | 1 (0–2) | |

| No dysphagia, n (%) | 162 (81.8) | |

| Dysphagia, n (%) | 36 (18.2) | |

| SDQ-15 item, median (IQR) | 1.5 (0.5–3.5) | |

| SDQ-14 item, median (IQR) | 0 (0–3) | |

| MSIS-29 (psychological scale), median (IQR) | 58.3 (44.4–66.7) | |

| MSIS-29 (physical scale), median (IQR) | 63.8 (56.3–71.3) | |

| SDQ Questions | 15-Item SDQ | 14-Item SDQ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha if Item Deleted | Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha if Item Deleted | |

| Q1 | 0.75 | 0.877 | 0.763 | 0.901 |

| Q2 | 0.624 | 0.883 | 0.637 | 0.906 |

| Q3 | 0.345 | 0.893 | 0.338 | 0.915 |

| Q4 | 0.531 | 0.887 | 0.529 | 0.91 |

| Q5 | 0.566 | 0.887 | 0.579 | 0.912 |

| Q6 | 0.66 | 0.882 | 0.667 | 0.905 |

| Q7 | 0.733 | 0.879 | 0.752 | 0.902 |

| Q8 | 0.6 | 0.887 | 0.61 | 0.909 |

| Q9 | 0.683 | 0.881 | 0.702 | 0.904 |

| Q10 | 0.647 | 0.882 | 0.648 | 0.906 |

| Q11 | 0.721 | 0.88 | 0.725 | 0.903 |

| Q12 | 0.708 | 0.881 | 0.688 | 0.905 |

| Q13 | 0.539 | 0.887 | 0.549 | 0.911 |

| Q14 | 0.709 | 0.881 | 0.725 | 0.904 |

| Q15 | 0.124 | 0.913 | - | - |

| Cronbach alpha (overall) | 0.892 | 0.913 | ||

| Item Number | Item Content | n (%) of Answers for Each Score | Factor Loadings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| 1 | Do you experience difficulty chewing solid food like an apple, cookie or a cracker? | 163 (82.3) | 26 (13.1) | 8 (4) | 1 (0.5) | 0.802 |

| 2 | Are there any food residues in your mouth, cheeks, under your tongue or stuck to your palate after swallowing | 167 (84.3) | 24 (12.1) | 6 (3) | 1 (0.5) | 0.798 |

| 3 | Does food or liquid come out of your nose when you eat or drink? | 188 (94.9) | 8 (4) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.789 |

| 4 | Does chewed up food dribble from your mouth? | 177 (89.4) | 17 (8.6) | 4 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.783 |

| 5 | Do you feel you have too much saliva in your mouth; do you drool or have difficulty swallowing your saliva? | 161 (81.3) | 22 (11.1) | 10 (5.1) | 5 (2.5) | 0.77 |

| 6 | Do you swallow chewed up food several times before it goes down your throat? | 174 (87.9) | 17 (8.6) | 6 (3) | 1 (0.5) | 0.747 |

| 7 | Do you experience difficulty in swallowing solid food (i.e., do apples or crackers get stuck in your throat)? | 174 (87.9) | 19 (9.6) | 4 (2) | 1 (0.5) | 0.724 |

| 8 | Do you experience difficulty in swallowing pureed food? | 188 (94.9) | 8 (4) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.704 |

| 9 | While eating, do you feel as if a lump of food is stuck in your throat? | 173 (87.4) | 19 (9.6) | 5 (2.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0.701 |

| 10 | Do you cough while swallowing liquids? | 155 (78.3) | 38 (19.2) | 4 (2) | 1 (0.5) | 0.684 |

| 11 | Do you cough while swallowing solid foods? | 175 (88.4) | 19 (9.6) | 3 (1.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0.634 |

| 12 | Immediately after eating or drinking, do you experience a change in your voice, such as hoarseness or reduced? | 179 (90.4) | 15 (7.6) | 3 (1.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0.609 |

| 13 | Other than during meals, do you experience coughing or difficulty breathing as a result of saliva entering your windpipe? | 153 (77.3) | 34 (17.2) | 9 (4.5) | 2 (1) | 0.593 |

| 14 | Do you experience difficulty in breathing during meals? | 181 (91.4) | 13 (6.6) | 3 (1.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0.382 |

| 15 | Have you suffered from a respiratory infection (pneumonia, bronchitis) during the past year? | No: 168 (84.8) | 30 (15.2) | - | ||

| SDQ | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age | Spearman’s rho | 0.136 |

| p-value | 0.057 | |

| Education | Spearman’s rho | −0.166 |

| p-value | 0.019 | |

| Age at onset | Spearman’s rho | 0.071 |

| p-value | 0.323 | |

| Disease duration | Spearman’s rho | 0.055 |

| p-value | 0.441 | |

| EDSS | Spearman’s rho | 0.388 |

| p-value | <0.001 | |

| DYMUS | Spearman’s rho | 0.62 |

| p-value | <0.001 | |

| MSIS-29 (psychological scale) | Spearman’s rho | −0.014 |

| p-value | 0.847 | |

| MSIS-29 (physical scale) | Spearman’s rho | −0.170 |

| p-value | 0.017 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mirmosayyeb, O.; Mohammadi, M.; Vaheb, S.; Shaygannejad, A.; Mohammadi, A.; Shaygannejad, V. Validation and Interpretation of the Persian Version of the Swallowing Disturbance Questionnaire in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. NeuroSci 2025, 6, 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040111

Mirmosayyeb O, Mohammadi M, Vaheb S, Shaygannejad A, Mohammadi A, Shaygannejad V. Validation and Interpretation of the Persian Version of the Swallowing Disturbance Questionnaire in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. NeuroSci. 2025; 6(4):111. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040111

Chicago/Turabian StyleMirmosayyeb, Omid, Mohammad Mohammadi, Saeed Vaheb, Aysa Shaygannejad, Aynaz Mohammadi, and Vahid Shaygannejad. 2025. "Validation and Interpretation of the Persian Version of the Swallowing Disturbance Questionnaire in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis" NeuroSci 6, no. 4: 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040111

APA StyleMirmosayyeb, O., Mohammadi, M., Vaheb, S., Shaygannejad, A., Mohammadi, A., & Shaygannejad, V. (2025). Validation and Interpretation of the Persian Version of the Swallowing Disturbance Questionnaire in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. NeuroSci, 6(4), 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040111