Development and Application of Urban Social Sustainability Index to Assess the Phnom Penh Capital of Cambodia

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Objectives

1.2. Theoretical Review

2. Materials and Methods

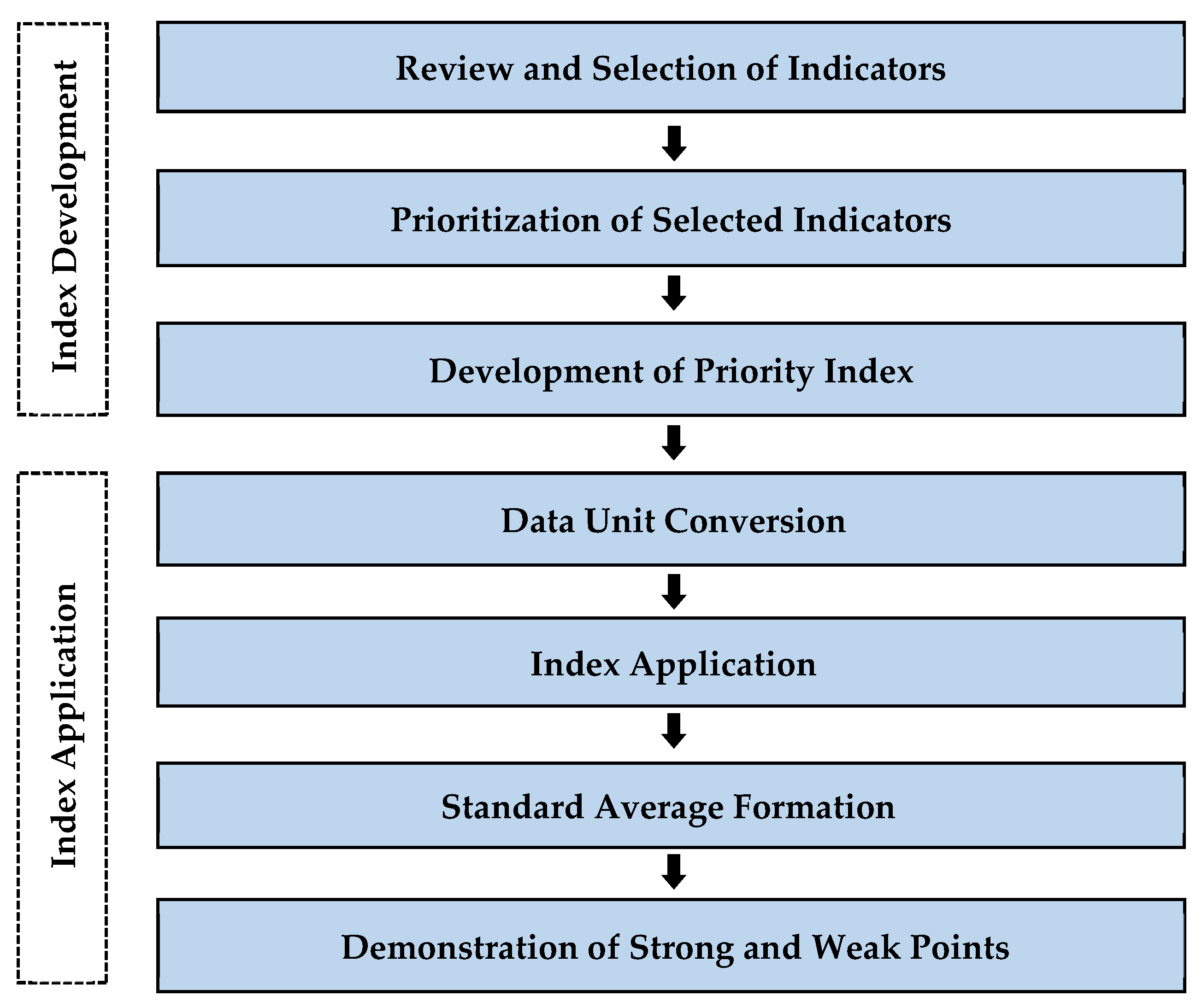

2.1. Analytical Framework

2.2. Development of Urban Social Sustainability Index

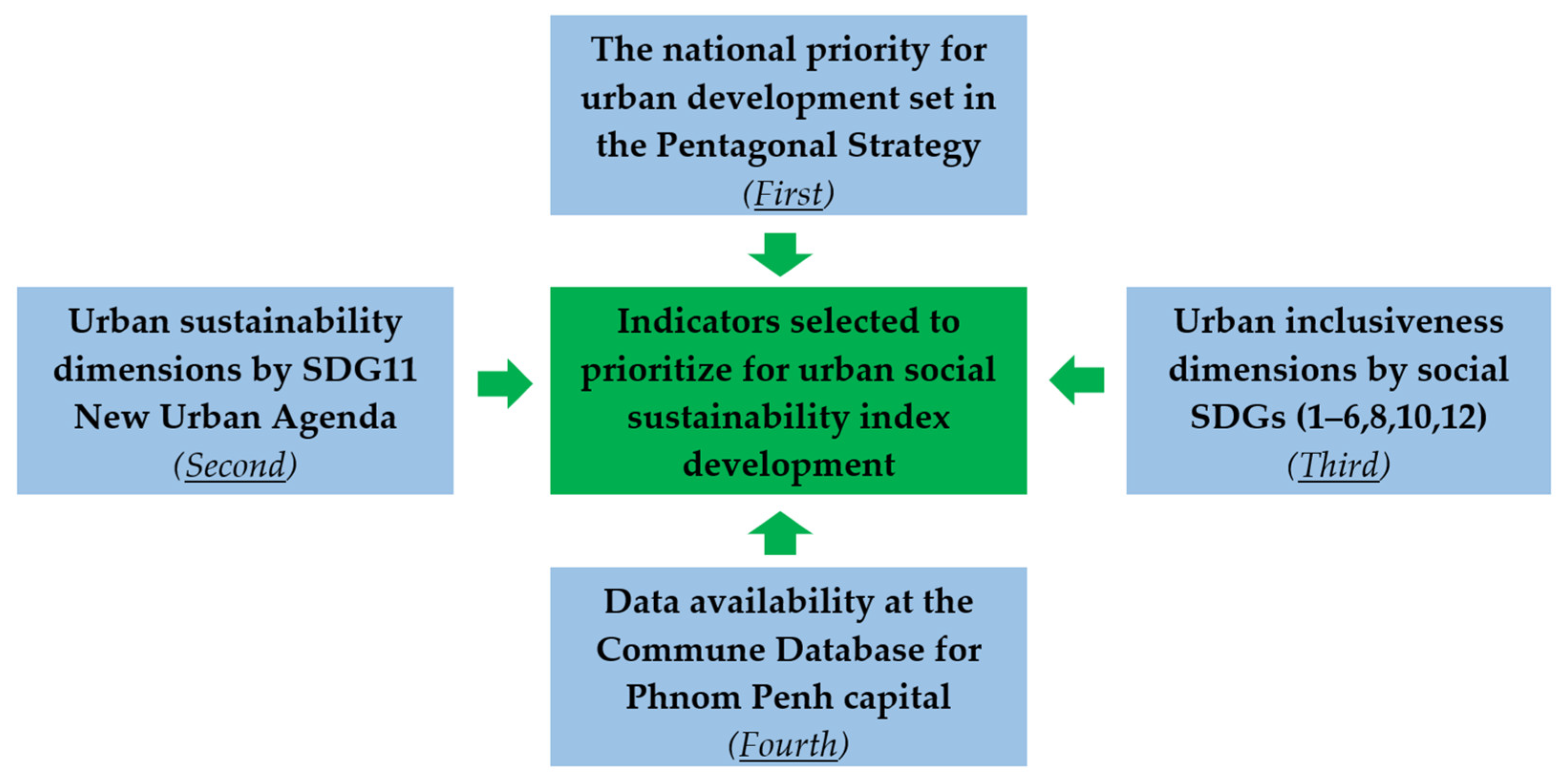

2.2.1. Indicator Framework

2.2.2. Indicator Prioritization for Index Development

2.3. Application of Urban Social Sustainability Index

2.3.1. Standard Z-Score Methods

2.3.2. Data Unit Conversion and Index Application

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Priority Weights of Urban Social Sustainability Index Development

3.2. Results of Urban Social Sustainability Index Application to Assess 14 Districts

3.2.1. Income Section

3.2.2. Gender Section

3.2.3. Welfare Section

3.2.4. Education Section

3.2.5. Vulnerability Section

3.2.6. Sanitation Section

3.2.7. Water Section

3.2.8. Safety Section

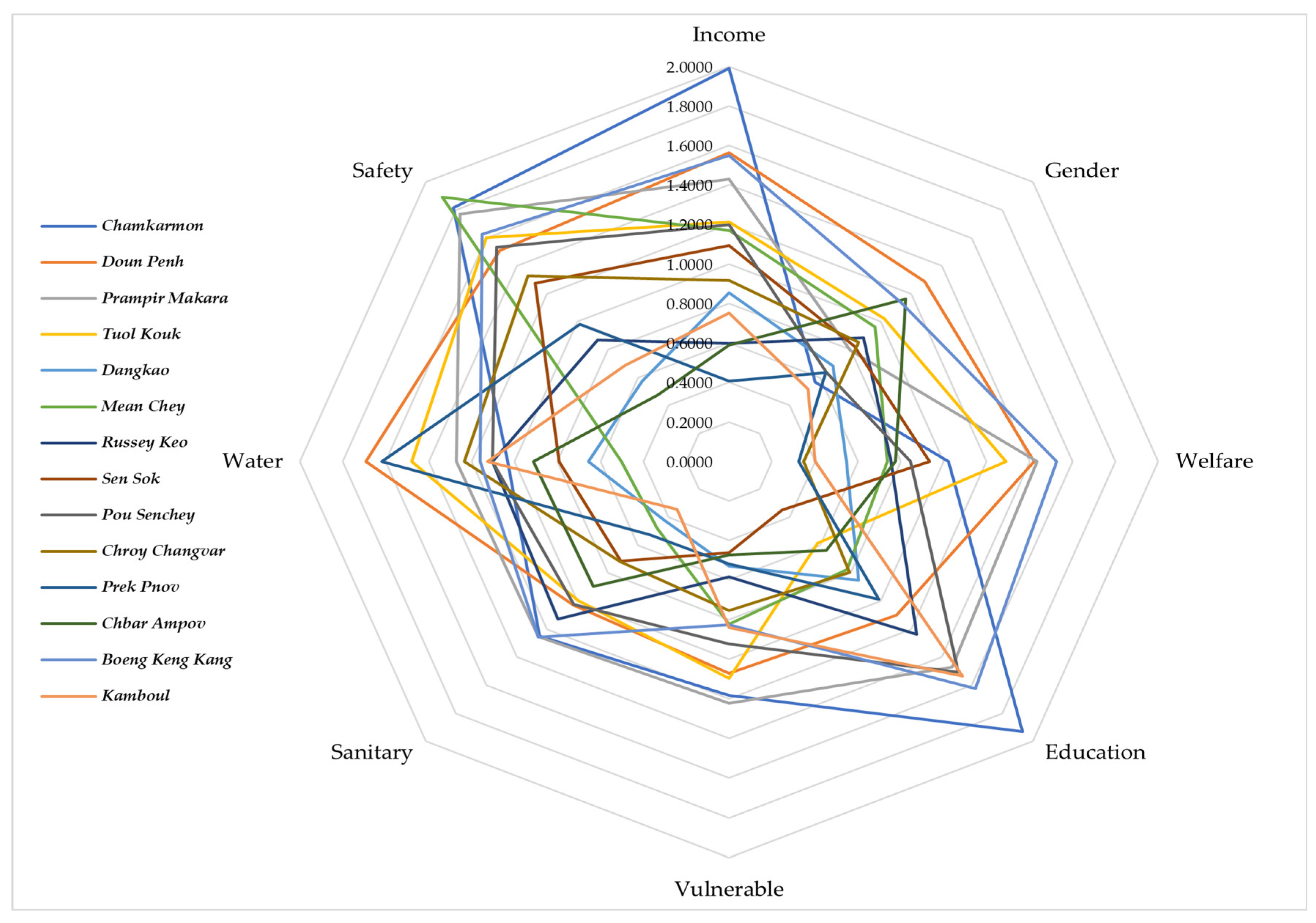

3.3. Overall Urban Social Sustainability Findings of 14 Districts

3.4. Urban Social Sustainability Ranking of 14 Districts

3.4.1. Section-Based Ranking

3.4.2. Consolidated Ranking

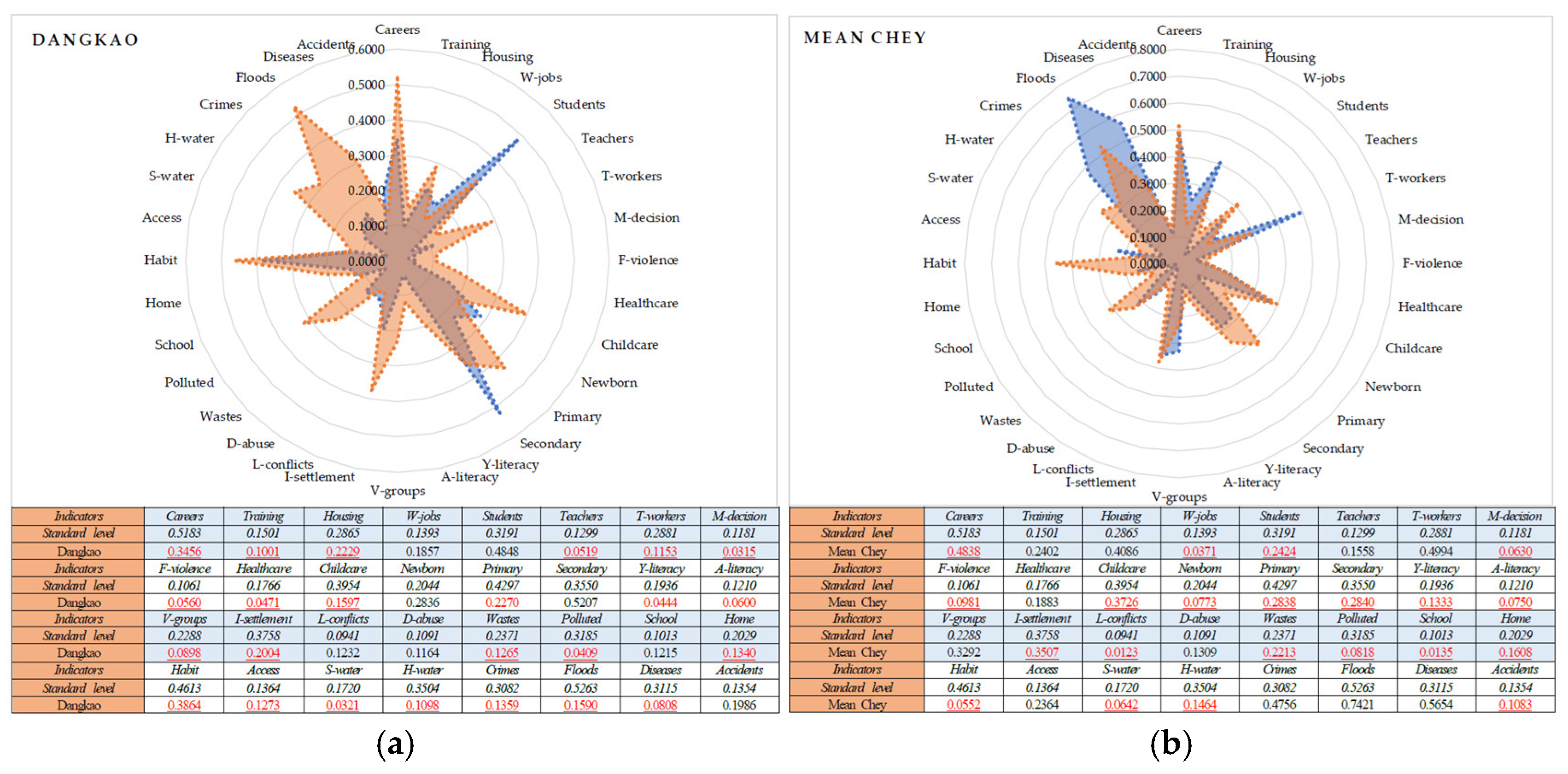

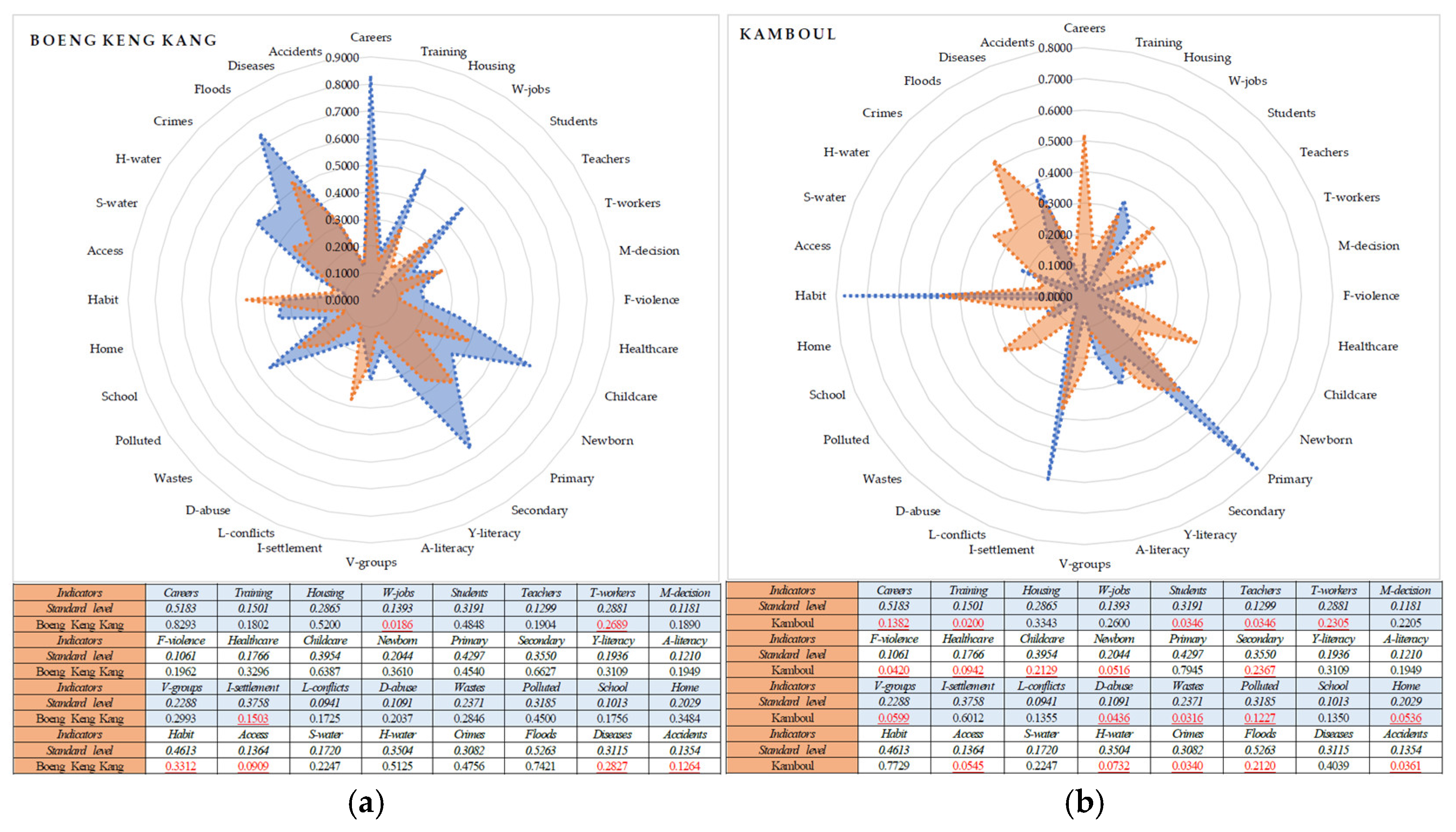

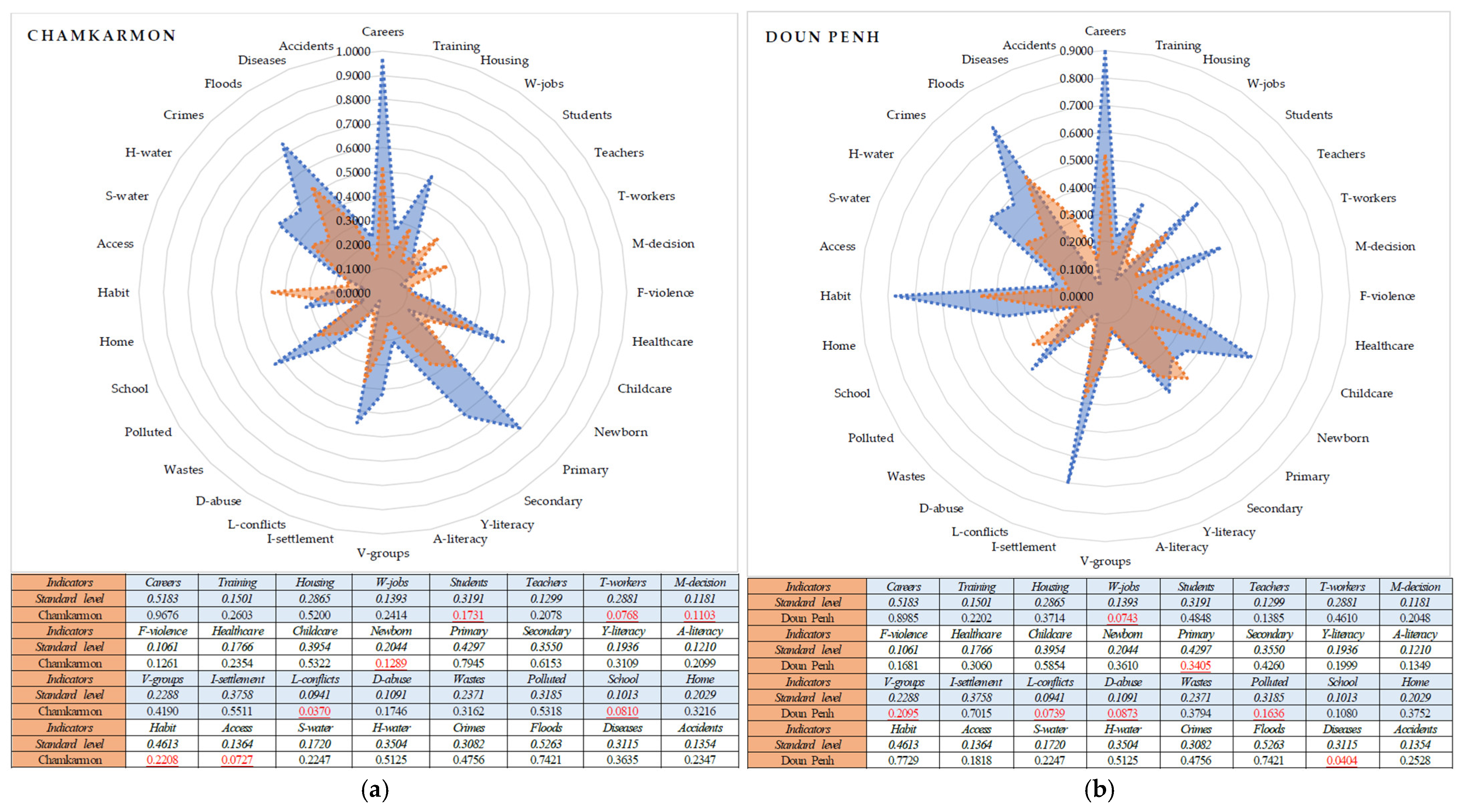

3.5. Strong and Weak Points of 14 Districts by Each Indicator

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Strong and Weak Points of Districts by Each Indicator

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Resolution adopted by the General Assembly; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Meuleman, L.; Niestroy, I. Common But Differentiated Governance: A Metagovernance Approach to Make the SDGs Work. Sustainability 2015, 7, 12295–12321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, S.; Parent, J.; Civco, D.L.; Blei, A.M. The Atlas of Urban Expansion; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 68% of the World Population Projected to Live in Urban Areas by 2050, Says UN. 2018. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/2018-revision-of-world-urbanization-prospects.html (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Richard, F. Does Urbanization Drive Southeast Asia’s Development? Available online: https://www.citylab.com/life/2017/01/southeast-asia-martin-prosperity-institute/511952/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Polèse, M.; Stren, R.E.; Stren, R. (Eds.) The Social Sustainability of Cities: Diversity and the Management of Change; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- de Fine Licht, K.; Folland, A. Redefining ‘sustainability’: A systematic approach for defining and assessing ‘sustainability’ and ‘social sustainability’. Theoria 2025, 91, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janoušková, S.; Hák, T.; Moldan, B. Global SDGs Assessments: Helping or Confusing Indicators? Sustainability 2018, 10, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. SDG Goal 11 Monitoring Framework. 2015. Available online: http://unhabitat.org/sdg-goal-11-monitoring-framework/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- UN-Habitat. SDG Goal 11 Monitoring Framework. A Guide to Assist National and Local Governments to Monitor Report on SDG 11 Indicators. 2016. Available online: https://www.local2030.org/library/view/60 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Chan, P.; Gulbaram, K.; Schuetze, T. Assessing Urban Sustainability and the Potential to Improve the Quality of Education and Gender Equality in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. The New Urban Agenda Illustrated. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/the-new-urban-agenda-illustrated (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- United Nations. New Urban Agenda: Habitat III, Quito, Ecuador, 17–20 October 2016. United Nations: New York, NY, USA; Available online: https://habitat3.org/wp-content/uploads/NUA-English.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Baker, J.L.; Kikutake, N.; Lin, S.X.; Johnson, E.C.; Yin, S.; Ou, N. Urban Development in Phnom Penh; The World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Menghoung, S.; Noer, M. A Study on Housing Affordability Problems among Working Households in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. J. Syntax. Lit. 2025, 10, 4435–4444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suon, M. Gender Disparities in Cambodian Higher Education (2015–2020): A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Enrollment, Performance, and Policy. J. Gen. Educ. Humanit. 2025, 4, 495–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouché-Lemieux, A.; Ouk, C.; Shinabargar, E. Enhancing City-Level Management and Urban Health Resilience: Multi-Sectoral Approach to Managing Mosquito-Borne Diseases in Phnom Penh Through the One Health Framework; Geneva Graduate Institute: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Asif, F.; Beckwith, L.; Ngin, C. People and politics: Urban climate resilience in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Front. Sustain. Cities 2023, 4, 972173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K.; Hofstad, H.; Zeiner, H.H.; Sagen, S.B.; Dahl, C.; Følling, K.E.; Olsen, B.O. Assessing urban social sustainability with the Place Standard Tool: Measurement, findings, and guidance. Cities 2024, 148, 104902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larimian, T.; Sadeghi, A. Measuring urban social sustainability: Scale development and validation. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2019, 48, 621–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larimian, T.; Freeman, C.; Palaiologou, F.; Sadeghi, N. Urban social sustainability at the neighbourhood scale: Measurement and the impact of physical and personal factors. Local Environ. 2020, 25, 747–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, L.; Gauntlett, E. Housing and Sustainable Communities Indicators Project: Stage 1 Report–Model of Social Sustainability; WACOSS (Western Australia Council of Social Services): Boorloo, Australia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, S. Social sustainability: Towards some definitions. In Hawke Research Institute, Working Paper Series No. 27; University of South Australia: Magill, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Akcali, S.; Cahantimur, A. The Pentagon Model of Urban Social Sustainability: An Assessment of Sociospatial Aspects, Comparing Two Neighborhoods. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N.; Bramley, G.; Power, S.; Brown, C. The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantonio, A. Urban social sustainability themes and assessment methods. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Urban Des. Plan. 2010, 163, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahramanpouri, A.; Lamit, H.; Sedaghatnia, S. Urban social sustainability trends in research literature. Asian Soc. Sci. 2013, 9, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcraft, S. Understanding and measuring social sustainability. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2015, 8, 133–144. Available online: https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/hsp/jurr/2015/00000008/00000002/art00004 (accessed on 8 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Atalay, H.; Gülersoy, N.Z. Developing social sustainability criteria and indicators in urban planning: A holistic and integrated perspective. ICONARP Int. J. Archit. Plan. 2023, 11, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P. The Development and Prioritization of Consensus Sustainable City Indicators for Cambodia. Ph.D. Thesis, Hanyang University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.M. A Study on the Development and Application of Evaluation Indicators for Sustainable Urban Development and Management. Ph.D. Thesis, Hanyang University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.J. Evaluation of Urban Growth Management in Metropolis of Korea. Ph.D. Thesis, Hanyang University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, February 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Government of Cambodia. Rectangular Strategy Phase IV for Growth, Employment, Equity and Efficiency: Building the Foundation Toward Realizing the Cambodia Vision 2050; Royal Government of Cambodia: Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2018.

- Royal Government of Cambodia. Pentagonal Strategy for Growth, Employment, Equity, Efficiency, and Sustainability; The Office of the Council of Ministers: Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2023.

- United Nations Capital Development Fund. CSDG Financing in Cambodia—Synthesis Report; United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF): New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, P. Cambodian Green Economy Transition: Background, Progress, and SWOT Analysis. World 2024, 5, 413–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal Government of Cambodia. Introducing the “Pentagonal Strategy–Phase I” and the “Key Measures of the Royal Government for the Seventh Legislature of the National Assembly” by Samdech Hun Manet, Prime Minister of Cambodia at the First Plenary Session of the Council of Ministers; Peace Palace: Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2023.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4). Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal4 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sustainable Development Goal 5 (SDG 5). Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal5 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Phnom Penh Capital Department of Planning. Phnom Penh Capital Socio-Economic Data; Phnom Penh Capital Department of Planning, Ministry of Planning: Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2019.

- Saaty, T.L. A Scaling Method for Priorities in Hierarchical Structures. J. Math. Psychol. 1977, 15, 234–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. The Analytical Hierarchy Process—What it is and how it isused. Math. Model. 1987, 9, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P. An Empirical Study on Data Validation Methods of Delphi and General Consensus. Data 2022, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goepel, K.D. Implementation of an Online Software Tool for the AHP: Challenges and Practical Experiences. Available online: https://bpmsg.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/ahp-software.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Soldatou, N.; Chatzianastasiadou, P.; Vagiona, D.G. Assessment of Carbon-Related Scenarios for Tourism Development in the Island of Lefkada in Greece. Tour. Hosp. 2022, 3, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Lee, D.; Lee, M.; Kim, M.; Kim, T. Analytic Hierarchy Process-Based Construction Material Selection for Performance Improvement of Building Construction: The Case of a Concrete System Form. Materials 2020, 13, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latinopoulos, D.; Vagiona, D. Measuring the sustainability of tourism development in protected areas: An indicator based approach. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 7, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagiona, D.; Doxopoulos, G. The development of sustainable tourism indicators for the islands of the Northern Sporades region in Greece. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2017, 26, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar]

- Vagiona, D.G.; Palloglou, A. An indicator-based system to assess tourism carrying capacity in a Greek island. Int. J. Tour. Policy 2021, 11, 265–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P.; Lee, M.-H. Developing Sustainable City Indicators for Cambodia through Delphi Processes of Panel Surveys. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P.; Lee, M.-H. Prioritizing Sustainable City Indicators for Cambodia. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P. Assessing Sustainability of the Capital and Emerging Secondary Cities of Cambodia Based on the Commune Database. Data 2020, 5, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P. Child-Friendly Urban Development: Smile Village Community Development Initiative in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. World 2021, 2, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, J. When Do You Need to Standardize the Variables in a Regression Model? Available online: https://statisticsbyjim.com/regression/standardize-variables-regression/ (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Taboga, M. Linear Regression with Standardized Variables. Available online: https://www.statlect.com/fundamentals-of-statistics/linear-regression-with-standardized-variables (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Ward, A.W.; Murray-Ward, M. Assessment in the Classroom; Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Claude, L.; Svitlana, P.; Joshua, E. Using the Normal Distribution, 2016, a Revision Version on Introduction to Statistics by Claude. 2017. Available online: https://openstax.org/details/books/statistics (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Kreyszig, E. Advanced Engineering Mathematics, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Statistics (NIS). The General Population Census of the Kingdom of Cambodia, 2019; National Institute of Statistics, Ministry of Planning: Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2019.

- Khmer Times. Clean City Competition Aims to Boost Tourism, Economic Growth. 2025. Available online: https://www.khmertimeskh.com/501772892/clean-city-competition-aims-to-boost-tourism-economic-growth/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- ASEAN Celebrates the 2nd ASEAN Environmentally Sustainable Cities Award. Available online: https://asean.org/asean-celebrates-the-2nd-asean-environmentally-sustainable-cities-award/ (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- ILO. Cambodia: Employment and Environmental Sustainability—Fact Sheets 2019; ILO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Cambodia—Achieving the Potential of Urbanization; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/935031540584687638 (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- UNDP. Cambodia’s Path to Sustainability: Accelerating National Priorities Through Climate Actions; UNDP: Phnom Penh, Cambodia; New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Reviewed Indicators | Shortened | Section |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ratio of employees in production and services per 1000 population | Careers | Income |

| 2 | Ratio of populations with vocational training per 1000 population | Training | |

| 3 | Percentage of households living in poor-quality houses | Housing | |

| 4 | Percentage of main and secondary jobs by Women (nonagricultural) | W-jobs | |

| 5 | Ratio of female students to male students at high schools and universities | Students | Gender |

| 6 | Percentage of female teachers who taught at primary and secondary schools | Teachers | |

| 7 | Ratio of Technical female workers to total employees in production and services | T-workers | |

| 8 | Percentage of commune/district council members (decision-making level) as women | M-decision | |

| 9 | Ratio of the number of households (Families) with violence per 1000 households | F-violence | Welfare |

| 10 | Ratio of pharmacies and clinics per 100,000 population | Healthcare | |

| 11 | Percentage of children joined childcare/kindergarten (aged 3–5) | Childcare | |

| 12 | Ratio of under-five mortality per 1000 births | Newborn | |

| 13 | Percentage of children enrolled at primary schools (aged 6–11) | Primary | Education |

| 14 | Percentage of children enrolled at secondary schools (aged 12–14) | Secondary | |

| 15 | Percentage of illiterate Youth (aged 15–24) | Y-literacy | |

| 16 | Percentage of illiterate Adults and middle-aged groups (25–45) | A-literacy | |

| 17 | Ratio of Vulnerable groups/people per 1000 population | V-groups | Vulnerability |

| 18 | Ratio of households informally settled/living on public land per 1000 households | I-settlement | |

| 19 | Ratio of Land conflict cases per 1000 households | L-conflicts | |

| 20 | Ratio of households having Drug-abuse members per 1000 households | D-abuse | |

| 21 | Percentage of households accessible to waste collection services | Wastes | Sanitation |

| 22 | Percentage of households affected by environmental pollution | Polluted | |

| 23 | Ratio of schools that installed proper toilets per 100 students | School | |

| 24 | Percentage of households that installed proper toilets | Home | |

| 25 | Percentage of households with potable water consuming habits | Habit | Water |

| 26 | Percentage of households located close to water sources (less than 150 m) | Access | |

| 27 | Percentage of Schools having potable water to use or drink | S-water | |

| 28 | Percentage of Households having potable water to use or drink | H-water | |

| 29 | Ratio of criminal cases per 100,000 population | Crimes | Safety |

| 30 | Ratio of households affected by floods per 1000 households | Floods | |

| 31 | Ratio of deaths by diseases per 100,000 population | Diseases | |

| 32 | Ratio of deaths by traffic accidents per 100,000 population | Accidents |

| Section | Income | Gender | Welfare | Education | Vulnerability | Sanitation | Water | Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 1/5 | 1/2 | 2 | 2 | 1 1/2 |

| Gender | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1/2 | 1 | 1 | 1/2 | 2/3 |

| Welfare | 1 | 1/2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1/2 | 2 |

| Education | 5/6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1/2 | 2 | 1 |

| Vulnerability | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1/2 | 1 | 1 | 1/2 | 1/2 |

| Sanitation | 1/2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1/2 |

| Water | 1/2 | 2 | 2 | 1/2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1/2 |

| Safety | 2/3 | 1 1/2 | 1/2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Section | Weight | Indicator | Weight | Priority Weight | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income | 0.1448 | Careers | 0.4771 | 0.0691 | 1 |

| Training | 0.1382 | 0.0200 | 21 | ||

| Housing | 0.2564 | 0.0371 | 11 | ||

| W-jobs | 0.1282 | 0.0186 | 22 | ||

| Gender | 0.1061 | Students | 0.3263 | 0.0346 | 13 |

| Teachers | 0.1632 | 0.0173 | 25 | ||

| T-workers | 0.3620 | 0.0384 | 10 | ||

| M-decision | 0.1485 | 0.0158 | 27 | ||

| Welfare | 0.1166 | F-violence | 0.1202 | 0.0140 | 30 |

| Healthcare | 0.2020 | 0.0235 | 19 | ||

| Childcare | 0.4566 | 0.0532 | 4 | ||

| Newborn | 0.2212 | 0.0258 | 18 | ||

| Education | 0.1413 | Primary | 0.4017 | 0.0568 | 2 |

| Secondary | 0.3350 | 0.0473 | 7 | ||

| Y-literacy | 0.1572 | 0.0222 | 20 | ||

| A-literacy | 0.1061 | 0.0150 | 28 | ||

| Vulnerability | 0.1069 | V-groups | 0.2800 | 0.0299 | 16 |

| I-settlement | 0.4687 | 0.0501 | 6 | ||

| L-conflicts | 0.1152 | 0.0123 | 32 | ||

| D-abuse | 0.1361 | 0.0145 | 29 | ||

| Sanitation | 0.1128 | Wastes | 0.2802 | 0.0316 | 15 |

| Polluted | 0.3625 | 0.0409 | 8 | ||

| School | 0.1197 | 0.0135 | 31 | ||

| Home | 0.2375 | 0.0268 | 17 | ||

| Water | 0.1260 | Habit | 0.4380 | 0.0552 | 3 |

| Access | 0.1443 | 0.0182 | 23 | ||

| S-water | 0.1274 | 0.0161 | 26 | ||

| H-water | 0.2904 | 0.0366 | 12 | ||

| Safety | 0.1454 | Crimes | 0.2336 | 0.0340 | 14 |

| Floods | 0.3645 | 0.0530 | 5 | ||

| Diseases | 0.2777 | 0.0404 | 9 | ||

| Accidents | 0.1242 | 0.0181 | 24 | ||

| Total | 1.0000 | - | 8.0000 | 1.0000 | - |

| Section | K01 | K02 | K03 | K04 | K05 | K06 | K07 | K07 | K09 | K10 | K11 | K12 | K13 | K14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income | ●●● | ●● | ● | |||||||||||

| Gender | ●●● | ●● | ● | |||||||||||

| Welfare | ● | ●● | ●●● | |||||||||||

| Education | ●●● | ●● | ● | |||||||||||

| Resilience | ●● | ●●● | ● | |||||||||||

| Sanitation | ● | ●● | ●●● | |||||||||||

| Water | ●●● | ● | ●● | |||||||||||

| Safety | ●● | ● | ●●● |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chan, P. Development and Application of Urban Social Sustainability Index to Assess the Phnom Penh Capital of Cambodia. World 2025, 6, 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6040167

Chan P. Development and Application of Urban Social Sustainability Index to Assess the Phnom Penh Capital of Cambodia. World. 2025; 6(4):167. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6040167

Chicago/Turabian StyleChan, Puthearath. 2025. "Development and Application of Urban Social Sustainability Index to Assess the Phnom Penh Capital of Cambodia" World 6, no. 4: 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6040167

APA StyleChan, P. (2025). Development and Application of Urban Social Sustainability Index to Assess the Phnom Penh Capital of Cambodia. World, 6(4), 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6040167