1. Introduction

The digital transformation of the public sector is a strategic necessity, especially in the context of an increasingly interconnected and technology-dependent society. Digital transformation ensures government transparency by allowing citizens to better understand and monitor activities in their relationship with public administration [

1]. In this process, emerging technologies are profoundly modernizing public administration. Every country faces different challenges, from culture to infrastructure, so blockchain technology offers a unique and personalized way to modernize the state.

Transferring cars, real estate, or valuables from one owner to another is fraught with complex bureaucratic regulations. In most countries, selling or donating these types of assets requires extensive paperwork, civil servants, and lawyers to verify these documents. In terms of public management, the use of blockchain changes the way institutional resources, services and processes are managed. Blockchain transparency increases the accountability of public officials and gives citizens greater control over how public resources are managed.

Cutting-edge technologies such as blockchain and AI agents are changing the way governments manage public records. In a decentralized ledger system, blockchain provides a secure, transparent, and immutable framework for storing and validating data [

2]. This technology eliminates the need for a central point of control, reducing the risks of corruption, fraud, and data loss. This ensures real-time access to verified information. Intelligent agents can automate traditional bureaucratic processes. Through rapid and accurate data analysis, AI can identify errors, omissions, or potential fraud, reducing the time required for manual checks and human intervention [

3]. Over time, agents become increasingly efficient through continuous learning to manage large volumes of government data beyond human potential.

Integrating blockchain with AI agents allows for the creation of an administrative ecosystem with a high degree of autonomy and transparency. This contributes to a significant reduction in administrative formalities and operational costs, both for citizens and for state institutions. The use of blockchain-based tokenization helps overcome the problems currently facing the global financial system [

4]. Fractional property purchases will be facilitated by tokenizing assets, these assets can be sent and exchanged with the highest level of security using a blockchain wallet [

5].

This paper proposes a novel approach for developing a decentralized property registry platform that streamlines property transfer processes. The novelty of our approach lies in the explicit coupling of blockchain-based via non-fungible tokens (NFTs) driven process automation, the proactive accommodation of regulatory constraints, and a modular microservices architecture for integration into public services. In this regard, the Framework outlines the stages of establishing and operating a decentralized registry, while emphasizing continuous stakeholder engagement and legal compliance assessment. The Method demonstrates how practitioners can conduct these phases by combining smart contract execution with intelligent agent assistance, enabling iterative refinement and guiding the platform toward full operational maturity. The approach undergoes evaluation through a six-month controlled pilot study and interdisciplinary expert review, combining technical validation with legal and policy-oriented analysis to assess its real-world feasibility. During the pilot phase, preliminary qualitative feedback was obtained from 20 domain participants, whose perspectives helped refine the system’s workflow and regulatory alignment. From a broader perspective, these evaluations indicate that the platform has potential to reduce bureaucratic complexity in property transactions, while also highlighting the need for continued refinement of certain legal and technical concepts to reach full institutional consensus. Additionally, qualitative insights corroborate the practical relevance of the system and offer recommendations for improving interface clarity and documentation, further strengthening the platform’s suitability for future public-sector integration.

Traditional property-registry processes remain slow, paper-dependent, and institutionally fragmented, requiring multiple intermediaries and manual verification steps that introduce delays, errors, and limited transparency. Existing blockchain-based pilots are typically implemented on permissioned ledgers, rely on centralized override mechanisms, and they rarely integrate AI-supported user interaction. As a result, a clear gap persists between technical feasibility and citizen-oriented, verifiable, and autonomous property-transfer systems.

To address this gap, the paper introduces a decentralized property-transfer framework in which NFT-based digital twins interact directly with on-chain execution, reducing reliance on intermediaries and enhancing auditability. The main contributions of this paper are:

Deployment on a public, permissionless blockchain (Ethereum) rather than a centralized solution used by public administration or a government ledger but permissioned. This ensure transparency, immutability, and citizen-controlled state transitions.

Encoding all legally relevant transfer logic directly into smart contracts, without centralized override paths, enabling trustless and auditable asset management.

Representing real-world property as NFTs functioning as digital twins, maintained in synchronization with a regulated registration process.

Integrating a Langfuse-orchestrated agentic AI assistant, capable of guiding users through complex legal steps, validating actions, and potentially reducing operational errors integrates a Langfuse-based AI assistant that guides users through legally structured workflows and reduces operational errors.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the existing literature on blockchain-based registries, NFTs, public-sector digital transformation, and related international pilot projects.

Section 3 presents the system architecture, smart-contract design, and implementation details.

Section 4 reports the experimental results, including performance benchmarks, gas-usage evaluation, and the user-study assessing the AI assistant.

Section 5 provides a discussion of the implications, limitations, and comparative positioning of the proposed framework. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research.

3. Implementation

The implementation of a government-grade, decentralized property registry using blockchain and NFT technology entails a sophisticated orchestration of modern web development, distributed systems engineering, and legal foresight. The project was developed as a single repository encompassing both a robust frontend in React and a secure backend powered by Ethereum smart contracts. This section provides a detailed breakdown of the technological layers and integration architecture.

Concerning the identity management, the prototype currently relies on MetaMask [

40] for authentication, which ensures cryptographic security but does not link blockchain addresses to verified legal identities. In contrast, production-grade digital registries integrate national electronic identity systems, such as Estonia’s eID or the European eIDAS [

41] framework, to confirm user legitimacy and prevent fraud. Incorporating decentralized identifiers (DIDs) or verifiable credentials issued by trusted authorities would bridge the gap between pseudonymous blockchain participation and legally recognized identity, thereby supporting compliance with know-your-customer (KYC) and anti-fraud requirements.

3.1. Methodology

The methodological approach adopted in this research was both theoretical and applied, combining conceptual modeling with practical implementation and comparative validation. The study began with a qualitative assessment of the inefficiencies inherent in traditional, paper-based property registration systems and their associated regulatory constraints. This diagnostic phase provided the empirical foundation for defining the technical and legal requirements of a blockchain-enabled alternative.

The implementation was designed to provide functionalities similar to pilots in Estonia, Georgia, the United Kingdom, and Dubai. The methodology thus bridged normative legal analysis with proven software engineering designs, ensuring that both governance implications and technical feasibility were tested

From a technical perspective, the system was designed and implemented using an iterative development methodology involving the necessary technologies for smart contracts, Ethereum blockchain, non-fungible token, a React-based user interface, AI-powered chatbot through Langfuse but guided through registration and ownership transfer procedures.

Overall, the methodological approach was pragmatic and multidisciplinary, grounded in blockchain architecture, legal informatics, and AI governance and aimed at producing not only a theoretical contribution but also a functional prototype capable of informing policy and large-scale deployment strategies.

3.2. System Overview Architecture

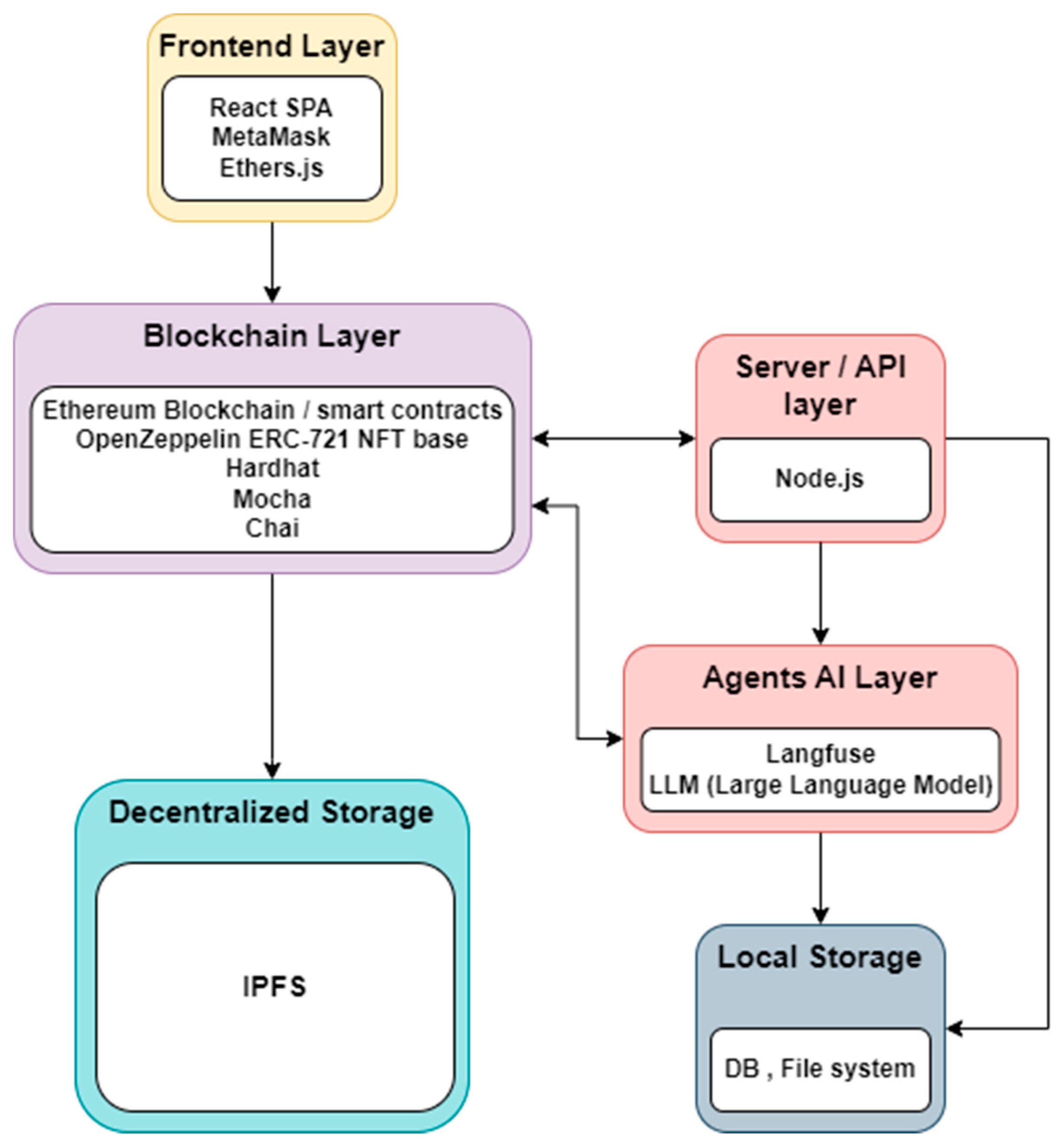

The architecture comprises the interdependent layers: the Frontend Layer, developed as a React single-page application with MetaMask and Ethers.js, manages user authentication and blockchain interaction; the Middleware/Server Layer, implemented in Node.js, orchestrates communication between users, AI agents, and the blockchain while coordinating off-chain processes; the Blockchain Layer hosts Solidity-based ERC-721 smart contracts for property registration and transfer; the Decentralized Storage Layer uses IPFS for storing NFT metadata, assets, ensuring scalability and data protection; and the Agents AI Layer, powered by Langfuse [

42] and large language models, provides conversational interaction. These modules form a continuous data flow where user actions in the front-end trigger API requests processed by the middleware, validated and executed on the blockchain, stored securely in IPFS or local storage, and interpreted by AI agents for transparency compliance.

In

Figure 1 is presented the system architecture and the main modules interaction.

The proposed system architecture is composed of five interdependent layers—Frontend, Middleware/Server, Blockchain, Decentralized Storage, and Agents AI—which collectively ensure usability, automation, transparency, and regulatory compliance. Each layer performs a distinct set of functions while maintaining seamless communication through standardized APIs and cryptographic protocols. The design emphasizes modularity and scalability, allowing the system to evolve alongside technological and legal requirements.

The Frontend Layer serves as the user-facing component and provides direct interaction between citizens, administrators, and the decentralized registry. Developed as a single-page React application (SPA), it delivers a responsive and intuitive interface for property registration, transfer, and verification. The integration of MetaMask enables secure user authentication, wallet management, and digital signature of transactions, ensuring that each action is cryptographically verifiable. Through Ethers.js, the frontend connects to the Ethereum blockchain and decentralized storage gateways such as IPFS APIs, translating user operations into blockchain transactions and retrieving on-chain data in real time.

The Middleware/Server Layer functions as a lightweight orchestration hub that mediates communication between the frontend, AI agents, and blockchain infrastructure. Built on Node.js, this layer manages off-chain coordination, executes business logic, and optimizes interactions that do not require on-chain execution. It also interfaces with Langfuse and large language models (LLMs) to process natural language requests and provide contextual responses. Furthermore, the middleware handles metadata pinning to decentralized storage and validates user inputs before signing or broadcasting them to the blockchain, thus maintaining data consistency and security across all layers.

At the core of the platform lies the Blockchain Layer, which ensures immutability, transparency, and decentralized control. Property assets are represented as ERC-721 non-fungible tokens (NFTs) developed in Solidity and secured through OpenZeppelin smart-contract libraries. This layer executes and records all ownership transfers on the Ethereum blockchain. Development and testing are conducted using Hardhat, Mocha, and Chai frameworks, which enable safe contract deployment and rigorous validation. The blockchain communicates bi-directionally with the middleware.

The Decentralized Storage Layer complements the blockchain by addressing scalability and compliance requirements. Using the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS), the platform stores NFT-related assets, metadata, and AI interaction logs off-chain while retaining verifiable cryptographic hashes on-chain. This hybrid architecture ensures that files and personal data remain accessible and secure without burdening the blockchain with excessive storage costs. The local storage is used for server backend functioning. The middleware layer coordinates pinning and retrieval of data from IPFS, while the frontend visualizes stored documents and records for end users through secure gateways.

Finally, the Agents AI Layer integrates cognitive automation into the system, enabling decision support and conversational interaction. Langfuse provides observability and workflow orchestration, logging all LLM prompts and responses for traceability. The LLM processes user inputs, formulates queries to the middleware, and interprets blockchain data to provide contextual guidance. The AI agents interact dynamically with the server layer to request contract status or retrieve stored information.

Together, these layers form a cohesive architecture where blockchain ensures trust, decentralized storage provides scalability, and AI agents deliver accessibility and automation.

The overall operational complexity of maintaining a system that integrates React front-end components, Ethereum smart contracts, InterPlanetary File System (IPFS) storage, Langfuse monitoring, and large language models should not be underestimated. Continuous integration, key management, and cybersecurity monitoring require high levels of technical expertise seldom available within public administrations. To manage these challenges, our early pilot deployment relies on managed cloud environments that provide scalability, compliance certification, and automated security updates. As institutional capacity and technical maturity grow, the system will gradually transition toward self-hosted, open-source implementations.

3.3. User Interface Layer

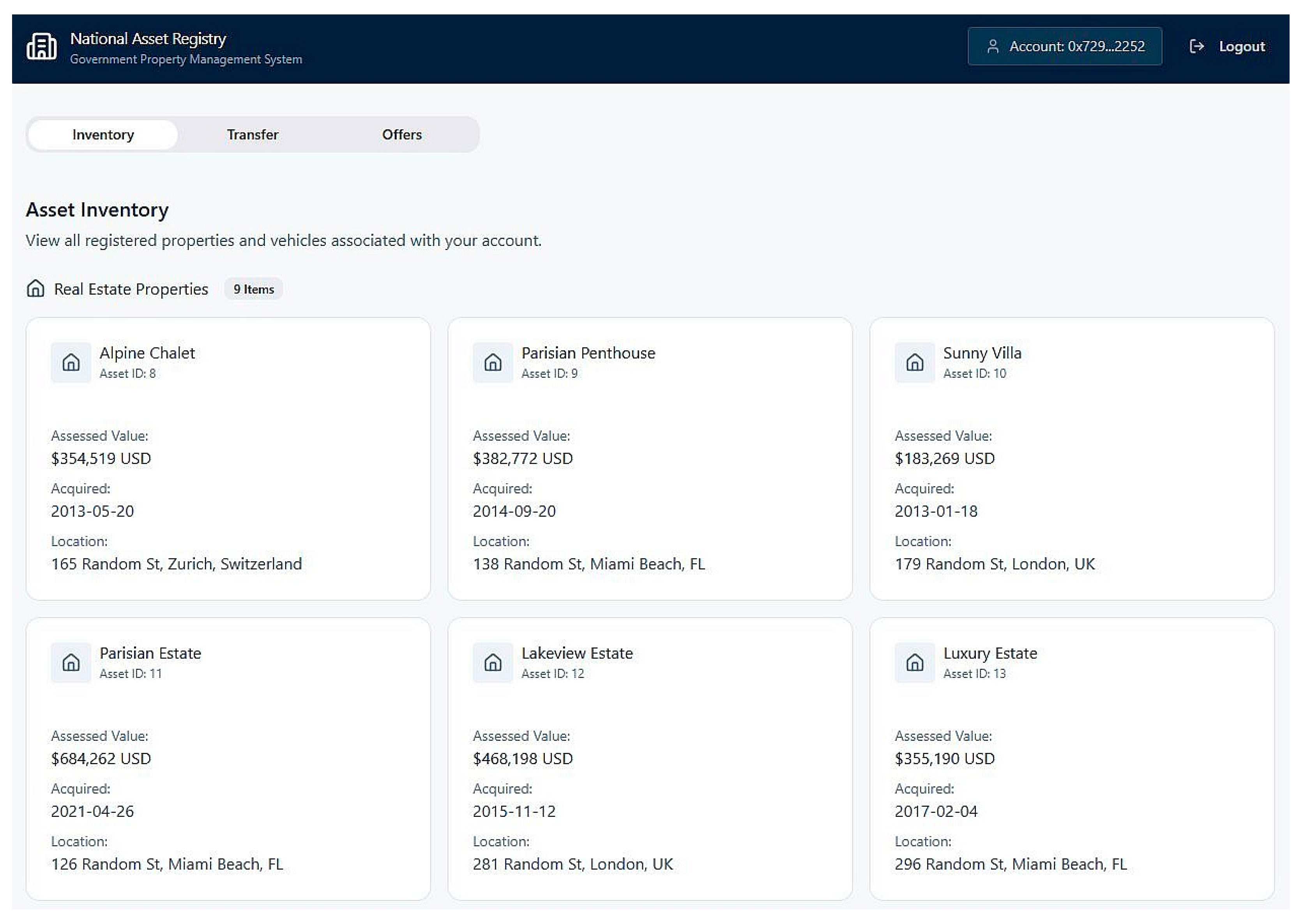

The user interface (see

Figure 2) was implemented in React, capitalizing on its strengths in modular component design and stateful, reactive views. The responsive SPA (Single Page Application) paradigm allowed for near-instant transitions between major functionalities, including inventory, asset transfer, offer management, and transaction history. Advanced user interactions were facilitated by React Router, which managed navigation, while context providers and hooks ensured global state, such as wallet connection and transaction status, remained consistent and up to date throughout the session.

The integration with the Ethereum blockchain occurred seamlessly via ethers.js, which served as the bridge between the user interface (UI) and the Ethereum network. MetaMask, a browser-based Ethereum wallet, provided cryptographic key management and transaction signing capabilities, ensuring that only authenticated users could execute state-changing operations. Authentication is currently handled via MetaMask, which securely manages cryptographic keys and transaction signing. The frontend was enhanced with libraries such as Framer Motion, which delivered modern animated transitions for modals and page navigation, and react-hot-toast, which offered user feedback for transaction states (e.g., pending, success, failure). Accessibility best practices were integrated into the UI, including Accessible Rich Internet Applications (ARIA) roles and keyboard navigation support, to ensure usability across a broad range of users.

The security architecture adopts a defense-in-depth paradigm, integrating multiple, mutually reinforcing control layers to mitigate both blockchain-native vulnerabilities and conventional application-layer threats. The primary assets under protection encompass document payloads, workflow and process metadata, user authentication tokens, smart contract logic, and cryptographic key material. A comprehensive threat analysis identifies principal attack vectors including first-mile data manipulation (document alteration prior to hash generation), unauthorized system or application programming interface (API) access, cryptographic key exposure or misuse, and sensitive metadata inference or leakage.

To provide a more operational and structured characterization of this approach, the system’s threat landscape has been analyzed across major attack categories—including smart-contract exploitation, unauthorized API access, key compromise, client-side manipulation, network-level interception, metadata tampering, service-availability disruptions, privacy leakage, business-logic abuse, and AI-specific vulnerabilities. For each category, corresponding mitigation mechanisms are defined through concrete, defense-in-depth controls spanning the smart-contract layer, authentication layer, API gateway, backend infrastructure, storage layer, and AI assistance module. A consolidated overview of these threats and their respective mitigation strategies is presented in

Table 1, with the protective controls implemented within the prototype being mentioned the first one.

From an operational perspective, the system enforces segregation of duties across administrative domains, supports continuous monitoring through Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) systems, and performs scheduled key rotation alongside periodic disaster recovery and business continuity exercises to ensure resilience against compromise or operational disruption.

Collectively, this layered security model ensures end-to-end data integrity, cryptographic non-repudiation, and verifiable accountability across all workflow stages, while preserving horizontal scalability and maintaining full regulatory alignment with General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and related data protection frameworks governing trusted digital record management.

To address GDPR and privacy concerns, personal information was deliberately excluded from on-chain storage. Instead, only hashed identifiers are recorded on the blockchain, while sensitive metadata remains in secure off-chain databases. The system employs zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs) to validate ownership or identity without exposing personal data, achieving functional alignment with European data-protection directives.

3.4. Blockchain and Smart Contract Layer

The backend of the application is decentralized and resided on the Ethereum blockchain, using Solidity smart contracts as the backbone of business logic. The core contract implemented the ERC-721 NFT standard, a widely recognized protocol for the creation and management of unique digital assets. In this context, every real-world property—be it a house, vehicle, or other tangible asset—was represented as an NFT, possessing metadata such as the asset type, descriptive information (e.g., address or VIN), appraised value, and owner’s blockchain address.

The synchronization between legal ownership records and the blockchain digital twin is implemented through a set of core smart-contract functions. These functions could translate validated legal events into regulated on-chain operations, ensuring consistency, auditability, and full compliance with institutional procedures. The following list outlines each function and its specific role within this process:

registerProperty(propertyId, owner, metadataHash): Creates a new digital twin by minting an NFT only after a registrar validates legal ownership. This function initializes the property’s metadata and establishes its first on-chain representation.

transferProperty(propertyId, newOwner, metadataHash): Executes a regulated ownership transfer based on legally recognized transactions. It updates both the NFT owner and the associated metadata to match the official registry.

correctMetadata(propertyId, metadataHash): Applies official corrections or updates to property attributes without altering ownership. This supports administrative amendments and ensures metadata remains legally accurate.

freezeProperty(propertyId): Temporarily disables transfer operations when a legal dispute or administrative hold is recorded. This guarantees that no blockchain changes contradict ongoing legal processes.

unfreezeProperty(propertyId): Restores transferability once the dispute is resolved or administrative hold is lifted. This function ensures synchronization between judicial decisions and blockchain state.

getPropertyHistory(propertyId): Returns a complete, immutable event log for the property’s digital twin. It ensures transparency and traceability for audits, compliance checks, and citizen access.

The system enforces a strict role-based permission model to ensure that every on-chain update is legally valid and accurately reflects the official property registry. This permission model ensures that the blockchain digital twin never diverges from the authoritative legal registry, while clearly defining which actors may initiate or authorize specific operations:

REGISTRY_ROLE: Assigned only to authorized national registry officials or accredited notaries. Required to execute any synchronization event, including registration, transfer, corrections, or dispute flags. This role guarantees that blockchain updates originate from legally recognized decisions.

OWNER_ROLE: Implicit role held by the wallet that currently owns the NFT. Used for user-initiated operations, but final registry-affecting actions must still be validated through REGISTRY_ROLE.

PUBLIC_ACCESS: All users may query property history and metadata. These read-only operations support transparency without compromising security.

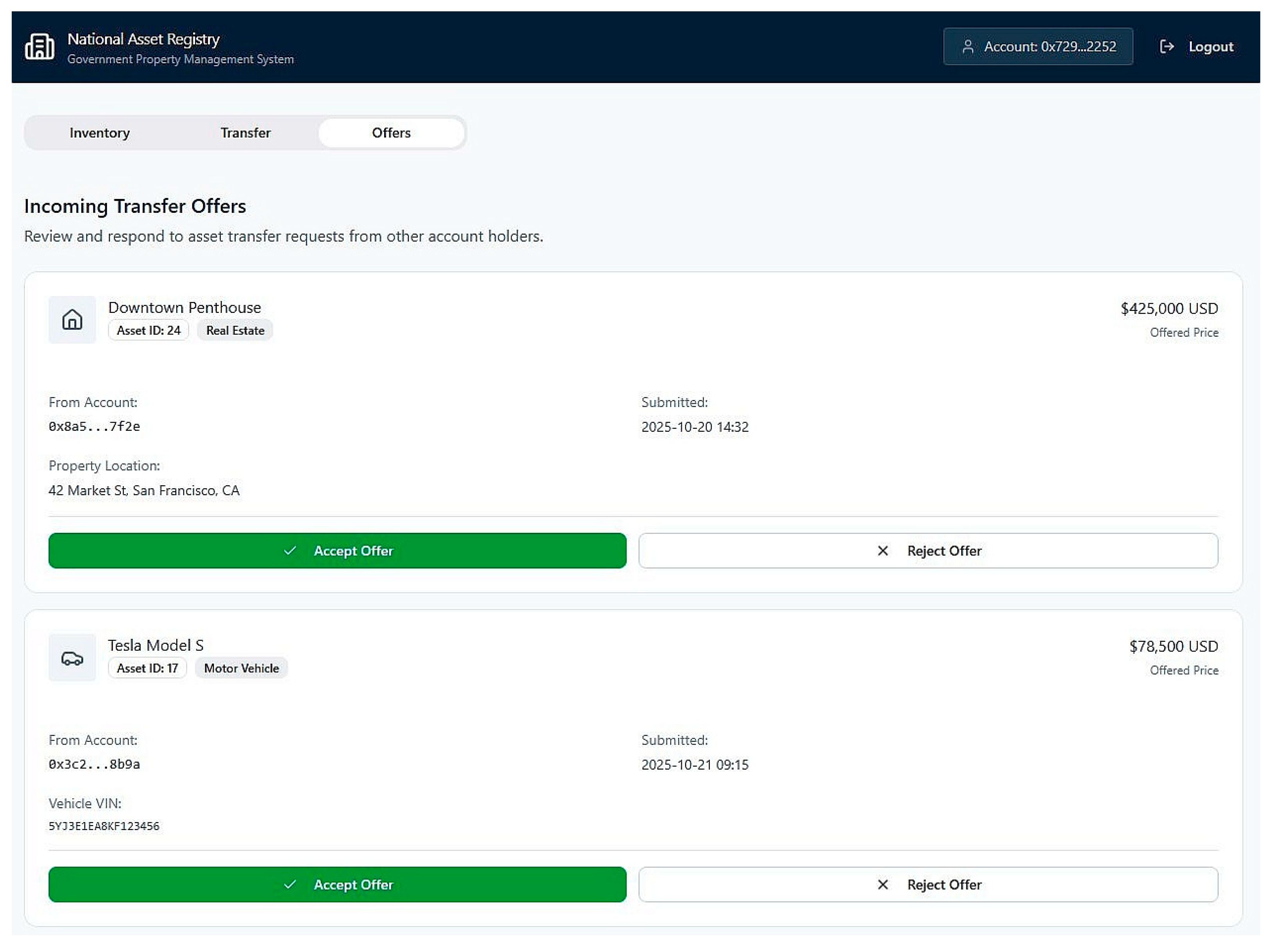

Ownership transfers (see

Figure 3) and offer creation were mediated by secure smart contract functions that employed access modifiers to prevent unauthorized actions. Each offer (see

Figure 4) or transfer required explicit digital signatures from both seller and buyer, thus removing the need for centralized notaries. The design adhered strictly to the Checks-Effects-Interactions pattern, thereby mitigating the risk of reentrancy attacks. Key contract events were emitted for every state change, allowing the frontend to subscribe and display real-time updates to users.

The synchronization logic shown in Algorithm 1 formalizes the technical pathway through which the NFT-based digital twin remains consistent with the legally recognized property record. Each legal event (such as registration, transfer, correction, or dispute) originates from a qualitative validation. As discussed in the policy analysis in

Section 4.1, real-life adoption requires that blockchain operations are tightly coupled with existing institutional procedures, ensuring that only trusted actors can initiate changes to the legal status of a property.

| Algorithm 1. Synchronize Digital Twin with Legal Registry Event |

Input: LegalEvent {propertyId, newOwner, metadataHash, eventType}

Require: Caller holds REGISTRY_ROLE issued by the national land authority

Ensure: Blockchain state remains consistent with legally validated ownership

1: Verify that the legal event has been validated by an authorized official

2: Check that the event complies with national property-transfer regulations

3: switch (eventType):

4: case REGISTER:

5: if propertyId is not yet registered then

6: mint new NFT representing the legal property

7: assign ownership to the validated legal owner

8: store metadataHash as authoritative registry data

9: end if

10: case TRANSFER:

11: verify that propertyId exists and is not frozen due to legal dispute

12: transfer ownership to newOwner as validated by the registry

13: update metadataHash to reflect new legal documentation

14: case CORRECTION:

15: update metadataHash following official corrections to legal records

16: case DISPUTE_OPEN:

17: mark the property as frozen to prevent unauthorized transfers

18: case DISPUTE_RESOLVE:

19: unfreeze the property to restore normal transfer operations

20: end switch

21: Record synchronization event on-chain to maintain an auditable history

22: Notify off-chain services and user interfaces of updated digital twin state |

To meet these requirements, the smart-contract layer enforces a strict REGISTRY_ROLE, which is granted only to certified authorities under the regulatory framework. This ensures that every on-chain update is triggered by an officially verified legal event, aligning the digital twin with the authoritative off-chain registry. Algorithm 1 captures these steps by first requiring administrative validation, then applying the appropriate on-chain transition: minting a new NFT for first registration, transferring ownership based on legally recognized transactions, updating metadata for corrections, or freezing assets during disputes.

The final steps of the algorithm emit synchronization events and notify off-chain services, creating a verifiable audit trail and enabling downstream applications, including the AI-assisted interface, to operate on up-to-date property information. As further emphasized in the Discussion, this integration between institutional validation, regulated smart-contract execution, and transparent on-chain auditing forms the backbone of a legally compliant and operationally viable decentralized property-registry system.

A first limitation concerns the legal–technical relationship between NFTs and actual property ownership. It is important to be aware that the transferring an NFT on the blockchain is not equivalent to transferring legal title. In current legal systems, however, blockchain tokens are not yet recognized as binding deeds of ownership. The existing pilots treat on-chain entries merely as verifiable digital proofs of rights recorded elsewhere. Consequently, NFTs should be regarded as digital twins of physical assets whose legal validity derives from synchronization with official registries and supporting legislation. Future work must therefore focus on developing APIs or oracle mechanisms capable of linking on-chain transactions to government databases and on advancing policy reforms that acknowledge cryptographically signed records as legally enforceable instruments.

The contract suite was thoroughly tested with Hardhat [

43], Mocha [

44], and Chai [

45], with tests covering expected functionality as well as edge cases, such as double-spending, unauthorized access attempts, or invalid transaction parameters. The code made use of the OpenZeppelin [

46] Contracts library, ensuring adherence to the latest best practices in security and compliance with the ERC-721 specification.

3.5. Integration and Data Flow

The data flow within the application was entirely on-chain, with no centralized database utilizes decentralized storage solutions like IPFS [

47]. All critical operations, such as asset minting, transfer, offer creation, and acceptance or rejection, were executed through Ethereum transactions. State was queried from the blockchain directly using ethers.js, providing trustless auditability and transparency. While metadata storage for more complex use cases (such as high-resolution property images or legal documents) the current MVP confines all essential information to on-chain storage (as hashes) to maximize simplicity and auditability.

To overcome concerns on-chain data storage and scalability; while some implementation stores all operational and metadata elements directly on the Ethereum blockchain to guarantee transparency, they are impractical at national scale. Full on-chain storage leads to high gas costs, limited throughput, and potential violations of privacy regulations such as GDPR. In contrast, our pilot project employs hybrid architectures in which only hashes or cryptographic proofs are written to the blockchain, whereas complete documents and rich media are retained in decentralized or government-managed repositories such as the IPFS. Adopting such a hybrid model maintains auditability while improving cost-efficiency and ensuring compliance with privacy law, including the right to rectification and erasure that immutable ledgers cannot provide.

A critical aspect of the integration layer was handling transaction status and error conditions. The frontend maintained a transaction manager component that polled the Ethereum network for pending and confirmed transactions, providing users with continuous feedback. This mechanism ensured that even users unfamiliar with the mechanics of blockchain could navigate the system with confidence.

3.6. Agentic AI Chatbot in a Blockchain-Based Property Registry

The integration of an agentic AI chatbot within our blockchain-based property registry was conceived to address real user needs: improving accessibility, reducing confusion, and automating information retrieval for processes that, in traditional systems, are deeply bureaucratic and intimidating to non-expert users. This section presents the technical architecture and implementation plan adopted in this project, emphasizing the synergy between the blockchain backend, the React-based user interface, and the Langfuse-powered AI agent.

The implemented solution is organized as a modular, service-oriented architecture, where the AI agent acts as an intelligent assistant layer on top of the dApp (decentralized application). The architecture comprises four main components:

The user interacts with a Single Page Application built in React, which manages navigation, on-chain data display, and user inputs. The application’s main modules—Inventory, Transfer, Offers, and Profile—each expose context-specific help triggers and chatbot entry points.

- 2.

Blockchain backend (Ethereum, Solidity):

All property and asset records, including transfer offers, are stored on the Ethereum blockchain. The system’s smart contracts, implemented in Solidity, define the minting procedures, ownership-transfer rules, offer lifecycle management, and event emission. These contracts expose a public Application Binary Interface (ABI) that enables interaction from both the frontend application and the AI assistant.

- 3.

Web3 interaction layer (Ethers.js):

Both the React frontend and the AI agent rely on Ethers.js to interact with the blockchain. This enables the agent to fetch asset information, transaction status, or even simulate transactions for the user, without requiring direct access to user credentials or private keys.

- 4.

Agentic AI layer (Langfuse + LLM):

The core of the intelligent assistant is built around a Large Language Model (LLM), orchestrated and monitored via Langfuse. The agent is hosted as a microservice, accessible over a secure REST API from the React app. User queries, system prompts, and context are sent to the agent, which then processes them, fetches on-chain data if needed, and formulates responses tailored to the ongoing workflow.

The agent is exposed through a dedicated API endpoint. The React application features a persistent chat widget (typically in the lower right of the UI) which maintains session state and passes context (active user, viewed asset, stage in transfer process) along with each query. This context-awareness allows the agent to offer proactive help, not just reactive answers.

When a user asks, for instance, “What is the status of my latest offer?” the chatbot agent parses the query, authenticates the user session, and makes a read-only call to the relevant smart contract via Ethers.js. No sensitive credentials are ever exposed; all on-chain reads are public and stateless, while any write actions are only prepared as suggestions for the user to confirm via MetaMask.

All LLM prompts and outputs are tracked and analyzed in Langfuse, which allows for auditability, performance monitoring, and continuous prompt improvement. Langfuse also enforces prompt templates that inject relevant contract ABI descriptions and usage examples into each LLM request, improving response accuracy for blockchain-related questions.

The agentic chatbot is programmed with scenario-based flows using prompt engineering and external tools (LangChain or similar). For example, if a user requests help with transferring a property, the agent can walk them step-by-step through verifying asset ownership, checking ETH balance for gas fees, preparing the offer transaction, and confirming the transaction in MetaMask.

All chatbot interactions are reflected in the UI in real time (

Figure 5). Errors, such as failed blockchain calls or insufficient funds, are explained in plain language, with suggestions for next steps. The agent proactively checks user actions against common pitfalls (such as invalid Ethereum addresses or attempting to transfer non-owned assets) before prompting the user to proceed.

Our adversarial testing strategy simulated edge-case scenarios in which the AI agent could potentially fail, including inconsistent or missing property attributes, conflicting ownership histories, incorrect or non-existent wallet addresses, and user prompts that intentionally misrepresented asset information. These tests were designed to expose failure points and ensure the agent does not execute unsafe, incorrect, or unauthorized actions within the registry workflow.

Equally significant are the reliability and safety of the integrated artificial-intelligence agent. Although the Langfuse-powered chatbot enhances usability, large language models remain susceptible to prompt-injection attacks, and misinterpretation of contextual data. In safety-critical environments such as property transfers, any erroneous advice could have material consequences. To mitigate these risks, the agent should operate within a restricted, read-only environment supported by retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) techniques that ground every response in verified blockchain data. Continuous auditing, adversarial testing, and explainability logging are also required to guarantee that the assistant’s behavior remains predictable and transparent.

5. Discussion

5.1. Policy Roadmap for Real-Life Adoption

An analysis of existing property legislation, notarial practices and public registry procedures was conducted to identify provisions requiring paper deeds, physical signatures, or centralized oversight. A pilot phased and multidimensional policy strategy was used for implementation, designed to bridge the gap between technical innovation and legal legitimacy:

Legislatures must conduct a comprehensive review of existing property law, notarial practices, and registry requirements. This process should identify where current statutes require paper deeds, physical signatures, or centralized oversight, and propose amendments to recognize cryptographic signatures and blockchain records as legally valid.

- 2.

Pilot Projects with Legal Standing

Governments should launch pilot programs granting legal recognition to blockchain-recorded transfers in specific regions or for limited asset classes. These pilots must be monitored for legal disputes, fraud attempts, and user experience challenges, with iterative feedback used to refine both the technical system and the legal framework.

- 3.

Regulatory Sandbox and Interagency Collaboration

A regulatory sandbox should be established to permit controlled experimentation with blockchain registries, with input from land/vehicle agencies, notaries, IT experts, and the judiciary. Such sandboxes allow agencies to test interoperability, resolve edge cases (e.g., contested ownership), and develop standards for dispute resolution in a digital context.

- 4.

Public Education and Digital Inclusion

Governments must develop training resources for legal professionals, notaries, and the public, explaining how blockchain-based registries work and how legal rights are enforced in a cryptographic environment. Digital inclusion must be prioritized, ensuring that citizens without advanced technical knowledge can participate through simplified interfaces based on artificial intelligence.

- 5.

Cross-Border Recognition and Harmonization

Especially in regions like the EU, cross-border harmonization is essential. Governments should collaborate to develop mutually recognized standards for blockchain-based property records, enabling property transfers and recognition across jurisdictions.

- 6.

Technical and Security Standards

Adoption of open, peer-reviewed smart contract standards (such as ERC-721), rigorous security audits, and mandatory public code review will help mitigate risks of exploits and ensure system integrity. Policies must also specify requirements for disaster recovery, key management, and long-term data durability.

- 7.

Gradual Phase-In and Parallel Operation

Legacy paper-based systems should operate in parallel with the new digital registry for an initial period, with robust mechanisms for cross-verification and recourse in case of error or attack. Transition plans must address how and when paper records are fully replaced by digital, on-chain ones.

- 8.

Continuous Evaluation and Policy Evolution

Ongoing evaluation—via public feedback, audits, and legal case analysis—will inform further policy development, ensuring that the system evolves in line with societal needs and technological advances.

Another crucial consideration involves compliance with data-protection regulations. Blockchain’s immutability conflicts inherently with GDPR provisions concerning data rectification and erasure. To achieve a balance between transparency and privacy, personal data should never be recorded directly on-chain. Instead, only hashed or pseudonymized identifiers should appear in the ledger, with sensitive information stored off-chain under strict access control. Advanced cryptographic tools such as ZKPs could then enable verification of ownership or identity without revealing the underlying data, strengthening both privacy and regulatory alignment.

5.2. Benefits and Limitations of AI Agent Integration

The integration of the agentic AI chatbot fundamentally transformed user interaction with the registry. Complex on-chain workflows that once required expert intervention can now be executed conversationally through the AI interface. By mediating user intent with contextual blockchain data, the agent enabled even first-time users to complete transfers securely and confidently without needing to understand smart-contract syntax.

In practice, the implementation incorporated enhanced safeguards for the AI assistant to ensure reliability and factual accuracy. By deploying RAG mechanisms grounded in verified blockchain data, the system eliminated hallucinations and maintained a transparent audit trail through Langfuse monitoring. All LLM prompts and responses are logged and continuously audited, guaranteeing that conversational interactions remain consistent with on-chain information and resistant to adversarial manipulation.

These improvements substantially increased usability and trust. The chatbot operates in read-only and pre-approved transaction modes, ensuring that users retain full control and authorization over blockchain interactions. This dual-layer control, combined with cryptographic signature validation through MetaMask, provided a transparent and non-repudiable workflow for all operations.

Compared with earlier international pilot projects, the present implementation achieved higher operational autonomy by embedding digital-identity verification modules based on Decentralized Identifiers (DIDs) integrated with national eID frameworks. This integration bridged the gap between pseudonymous blockchain addresses and legally verified identities, ensuring compliance with KYC and data-protection regulations. As a result, property transfers executed through the AI-assisted interface are now both legally traceable and cryptographically secured.

The AI-agent framework also incorporated an arbitration protocol for dispute resolution. In the rare event of contested ownership or technical failure, authorized adjudicators can trigger a smart-contract-based review process using multi-signature validation. This hybrid model maintained the trustless nature of on-chain operations while ensuring that legitimate human oversight remained available when required by law.

Collectively, these enhancements positioned the AI integration not only as a usability layer but as a compliance and governance enabler, demonstrating that conversational interfaces can coexist with strict regulatory and legal standards.

The AI agent fundamentally transforms user interaction, allowing complex on-chain workflows to be navigated conversationally rather than through static forms. By mediating user intent with contextual blockchain data, it ensures that even novice users can safely and efficiently complete property transfers, check balances, or resolve errors without needing to understand smart contract internals. The use of Langfuse and a rigorous observability layer ensures that agent behavior is transparent, improvable, and safe from adversarial manipulation.

Although the agentic chatbot significantly improves usability, it is strictly limited to advisory and automation roles. It cannot execute blockchain transactions without explicit user approval. Performance is subject to the latency of LLM responses and blockchain RPC calls, and there remains the ongoing need to prevent “hallucinated” or inaccurate agent answers—especially when dealing with real assets. Future work may integrate on-chain identity systems for regulatory compliance, multi-language support, and deeper error recovery mechanisms.

Compared to pilot land registry digitization efforts in Estonia, Dubai, and Georgia, which often depend on permissioned blockchains and central agency APIs, this pilot project demonstrates a more decentralized, user-empowering approach. While those implementations have made significant strides in automating land record management, they rarely combine direct user-to-blockchain interaction with an AI-powered conversational agent capable of interpreting, explaining, and guiding legal and financial transactions. The present solution thus advances the state of the art, combining the transparency of public blockchains with the accessibility of modern AI assistants, all managed within a robust, modular microservices architecture.

To improve our solution regulatory alignment with GDPR’s right to rectification and erasure, we store only non-personal hashes on-chain, and the personal data remains off-chain. We acknowledge GDPR compliance as partial and context-dependent since the officials using the system are signing using their function, no personal identity.

5.3. Use Case: Implementing the Agentic Chatbot with OCI Generative AI

The integration of a managed cloud AI service such as OCI Generative AI extends the scalability, reliability, and governance readiness of the property-registry platform. Rather than relying on standalone observability and orchestration layers, the system leverages OCI’s managed LLM endpoints (such as Cohere [

49], Llama [

50], or Oracle’s [

51] models) to provide a stable foundation for conversational interaction and automated workflow assistance. Through this architecture, the registry benefits from continuous performance monitoring, built-in security hardening, and compliance controls enforced by OCI Identity and Access Management (IAM), reducing operational burden while meeting government-grade requirements.

Within the application, the React-based chatbot widget communicates with OCI’s Generative AI service via secure HTTPS requests. Each interaction transmits contextual information—such as the user’s current workflow stage or on-chain property data—to enable accurate and situationally aware responses. Prompt-engineering techniques were refined to inject smart-contract ABI fragments, transaction templates, and real-time blockchain metadata, ensuring that the AI assistant remains grounded in verified system state when guiding users through property registration, ownership transfer, or dispute-resolution scenarios.

Observability and auditability are handled natively by OCI’s monitoring tools, which track prompt behavior, latency, and model performance without requiring separate platforms. This consolidation simplifies system operations while maintaining transparent and traceable AI behavior, a critical requirement for applications deployed in legally sensitive public-administration environments.

By delegating model hosting, versioning, and security patching to the OCI cloud, the registry avoids the maintenance challenges associated with custom LLM deployments. The managed-service approach ensures that the conversational assistant remains operational even under high load, while strong isolation guarantees that sensitive blockchain-related information remains protected.

Through these integrations, the decentralized property-registry system evolves into a more robust and production-ready environment. The AI assistant becomes not only a usability feature but also an instrument for regulatory alignment, supporting citizens and officials through complex legal workflows with improved accuracy, transparency, and operational efficiency.

5.4. Technical Limitations and Future Improvements

Although the proposed blockchain-based property registry demonstrates strong potential to modernize public administration, several technical limitations remain when the prototype is compared with proven national implementations such as those in Estonia, Georgia, the United Kingdom, and Dubai. These limitations arise from differences between conceptual design and the operational, legal, and infrastructural realities that characterize large-scale deployment. Addressing them is essential for transforming the framework from an experimental proof of concept into a production-ready public service.

Scalability and cost efficiency further limit the practicality of deploying the platform on the public Ethereum mainnet. The network’s variable gas fees, transaction latency, and energy consumption render it unsuitable for mass adoption in national registries. Empirically successful initiatives rely instead on permissioned or consortium blockchains, such as Hyperledger Fabric or Quorum, or on Ethereum Layer 2 networks like Polygon, Optimism, and Arbitrum, which preserve compatibility while reducing costs and improving performance. Evaluating these alternatives and quantifying their operational impact should be a priority in the subsequent development phases for our real-life implementation.

In summary, the proposed platform introduces a pioneering synthesis of blockchain, AI-mediated interaction, and public-sector transparency. Nevertheless, successful transition from pilot phase to real-world deployment demands small scale refinements. Legal recognition of NFT-based ownership (if nor still usage as digital twins), hybrid storage architectures, verified digital identities, formal dispute-resolution procedures, scalable network selection, and maintaining GDPR-compliant data handling (as implemented already in the pilot phase) all constitute necessary next steps. Addressing these factors, open-standard adoption, and close collaboration between technologists, policymakers, and legal experts will enable the framework to evolve from a promising prototype into a resilient, trustworthy, and institutionally integrated digital property registry.

As a future work, we will focus on transaction finality and dispute resolution. Because Ethereum transactions are irreversible, there is no native mechanism to correct fraudulent or erroneous transfers once executed. Real-world land registry systems, by contrast, preserve a form of administrative or judicial override to ensure legal redress. The proposed system will therefore integrate a governance layer that enables controlled intervention in exceptional cases. This could take the form of smart-contract-based arbitration modules or multi-signature schemes that require authorization from both transacting parties and a designated adjudicator. Such features would balance the transparency of decentralized systems with the accountability demanded by public institutions.

6. Conclusions

Blockchain is an emerging technology that has become a catalyst for the strategic digital transformation of the public sector. By integrating it into existing public systems, public management is improved and administration is modernized, for the direct benefit of taxpayers.

This work addresses the persistent inefficiencies of paper-based property registration and ownership transfer by embedding legal and administrative logic within smart contracts and automating compliance through an intelligent conversational interface. The system was implemented using Ethereum-based ERC-721 standards, React for the user interface, and Langfuse-powered AI integration for guided user interaction. Pilot deployments demonstrated secure, transparent, and auditable transactions executed entirely on-chain, while hybrid storage through IPFS and identity verification via decentralized identifiers ensured privacy and legal validity. Comparative analysis with existing national initiatives validated that the proposed architecture offers decentralization, citizen control, and interoperability without sacrificing regulatory compliance. The implementation leads to less bureaucracy, effortless transactions, and reduced human error rates, while enhancing accountability and public trust.

For a government-scale digital property registry, starting with a managed cloud AI service is often preferable for rapid prototyping, regulatory compliance, and minimizing operational risk. For final national-scale deployments with sensitive data or unique workflow needs, migrating to a self-hosted, highly customizable stack may become preferable as the project matures.

The adoption of emerging technologies in the public sector is a necessity to modernize traditional administration. Digitalization through AI agents and blockchain allow the creation of faster, more secure and more citizen-centric public services, contributing to increasing trust in state institutions and accelerating the digital transformation of society. The Romanian state must modernize and adopt various applications that reduce tax evasion and streamline tax collection in several economic sectors, because it is at record levels for a European country. Tax evasion in Romania is estimated at approximately 7.8 billion euros, which represents 10% of the country’s GDP [

52]. These data show a persistent problem, with a significant impact on budget revenues and the competitiveness of the Romanian economy.

In essence, this work presents how the integration of blockchain and artificial intelligence can redefine the social contract between citizens and the state. By transforming property registration into a transparent, autonomous, and citizen-driven process, the platform moves beyond digital efficiency to foster institutional trust and sustainable governance. The integration of smart contracts, NFT-based ownership models, and AI-assisted compliance creates an ecosystem where property rights are verifiable, corruption-resistant, and accessible to all. These technologies offer not only technical innovation but a pathway toward more equitable and accountable public management. The pilot phase of this project shows that digital transformation can serve as a cornerstone of a modern state that is efficient, transparent, and truly aligned with the public interest.

The evaluation results indicate that the proposed framework presents measurable improvements in both operational efficiency and user interaction reliability. Controlled testing showed that the AI-assisted workflow reduced task completion time for property transfers from 164 s to 109 s (−33.5%), lowered required user actions from 14.1 to 8.3 (−41.1%), and decreased error rates from 15% to 5% (−66.7%), demonstrating substantial usability gains. Gas-usage analysis further confirmed the economic feasibility of the core on-chain functions, with average costs of approximately 200k gas for property registration, 77.5k gas for ownership transfer, 42.5k gas for metadata correction, and 30k gas for freeze/unfreeze operations, while getPropertyHistory remained cost-free due to its read-only nature. Complementary RPC-level benchmarking on Sepolia showed consistent network responsiveness, with latency measurements averaging 0.7–1.1 ms, supporting real-time interaction even under load.

Future research should extend the present work in several complementary directions to support the transition from a technical prototype to a legally recognized, production-grade property-registry system. First, scalability must be evaluated through comparative benchmarking of Layer-2 rollups (e.g., Optimism, Polygon, Arbitrum) and hybrid permissioned–public architectures to determine the most appropriate infrastructure for national-scale deployments with millions of assets. Second, real-world adoption requires robust governance and dispute-resolution mechanisms; therefore, forthcoming work should design and assess multi-signature arbitration modules, supervised override procedures, and legally compliant smart-contract upgradability models. Finally, interoperability standards represent a critical next step. Future studies should investigate cross-registry APIs, metadata schemas, and cross-chain protocols capable of enabling cooperation between land registries, municipal authorities, notarial systems, and financial institutions, ultimately supporting multi-jurisdiction digital property transfers.