Innovations in Non-Motorized Transportation (NMT) Knowledge Creation and Diffusion

Abstract

1. Introduction

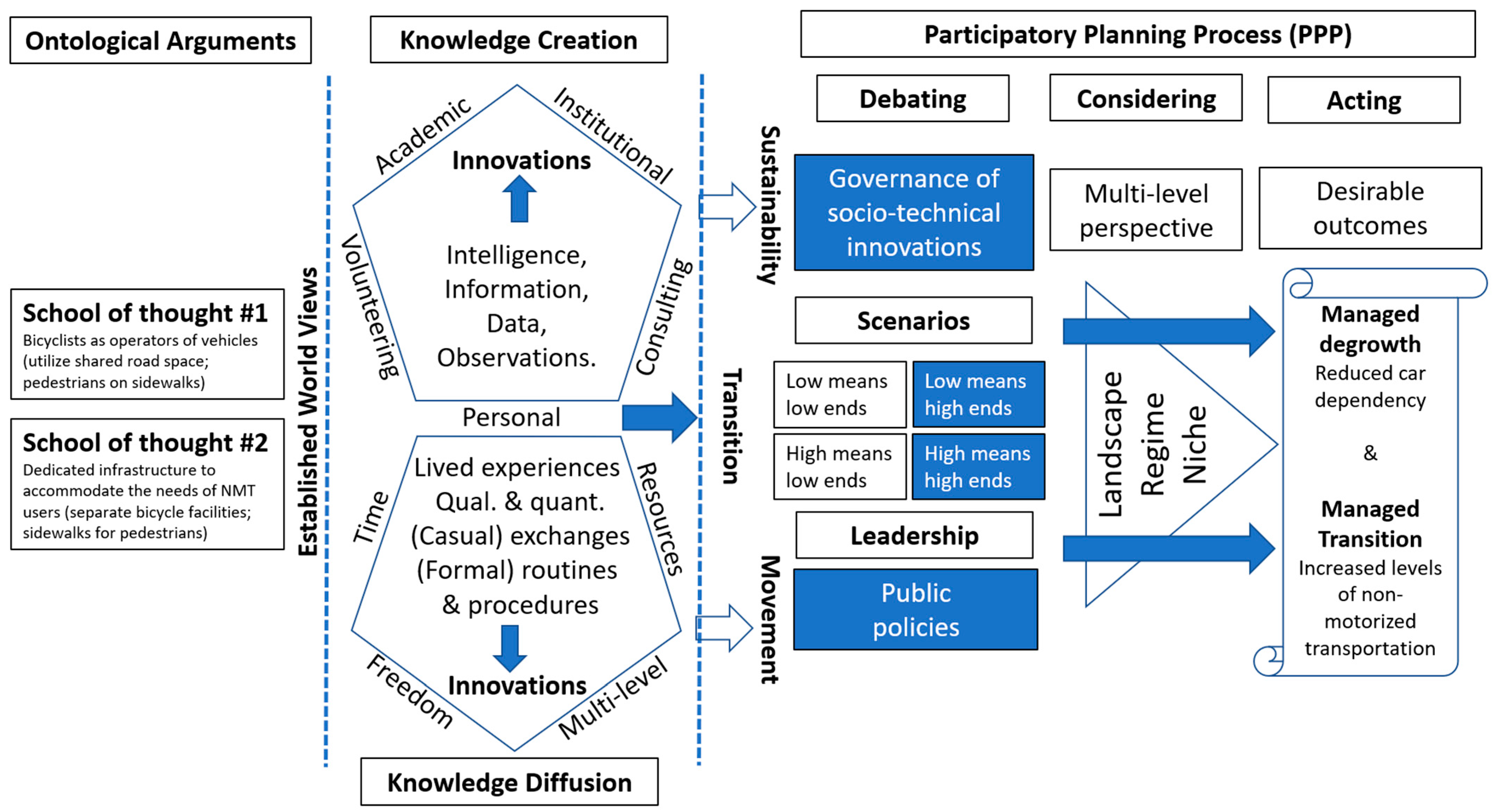

2. Methods and Analytical Mechanism

2.1. How to Encourage More Bicycling

2.2. How to Shape Public Policy by Creating and Diffusing Knowledge

3. Realms

3.1. Personal (Lived Experience)

3.2. Academic (Didactic Realm)

3.3. Institutional (Reformist)

3.4. Volunteering (Grassroots Advocacy)

3.5. Private (Commodified and Unsanctioned Activities)

4. Comparative Discussion and Scenarios for NMT Sustainable Transitions

4.1. Low Means, Low Ends

4.2. Low Means, High Ends

4.3. High Means, Low Ends

4.4. High Means, High Ends

| Landscape | Regime | Niche | Desirable Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chaotic transition [Low means, low ends] | Generalized collapse | Collapse of interim regimes | No new technologies | Risk of not accomplishing anything positive |

| Managed degrowth [Low means, high ends]—likely outcome: (un)desirable automobility | Shortage of resources and some regulation | Phased deconstruction of regime actors | Potentially significant innovation | High level of experimentation and low risk of failure |

| Business as usual [high means, low ends] | Low probability of fostering positive change | Stable membership in regime actors | Some niche technologies | Uncommitted activities and actions |

| Managed transition [high means, high ends]—likely outcome: desirable NMT | Sustainable mobility on a grand scale | Strong regulation and policy (funding) | Strong encouragement of new technologies (bike boulevards, skyways, etc.) | Higher certainty of accomplishing positive outcomes |

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ali, S.H.; Connolly, C.; Keil, R. Pandemic Urbanism: Infectious Diseases on a Planet of Cities; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bratton, B. The Revenge of the Real: Politics for a Post-Pandemic World; Verso Books: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Diffenbaugh, N.S.; Field, C.B.; Appel, E.A.; Azevedo, I.L.; Baldocchi, D.D.; Burke, M.; Burney, J.A.; Ciais, P.; Davis, S.J.; Fiore, A.M.; et al. The COVID-19 lockdowns: A window into the Earth System. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzmann, K.R. Smart cities after COVID-19: Ten narratives. disP 2020, 56, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, T.S.; Pardo, P. Shifting streets COVID-19 mobility data: Findings from a global dataset and a research agenda for transport planning and policy. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021, 9, 100322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shark, A.R. Technology and Public Management; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nasr, J.; Volait, M. (Eds.) Urbanism: Imported or Exported? Academy Press: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, O.P. (Ed.) Handbook of Policy Transfer, Diffusion and Circulation; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt, L. Importing ideas: The transnational transfer of urban revitalization policy. Int. J. Pub. Admin. 2006, 29, 221–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T.; Cook, I.R.; McCann, E.; Temenos, C.; Ward, K. Policies on the move: The transatlantic travels of tax increment financing. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2016, 106, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossberger, K.; Wolman, H. Policy transfer as a form of prospective policy evaluation: Challenges and recommendations. Public Adm. Rev. 2003, 63, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajer, M.A. The Politics of Environmental Discourse: Ecological Modernization and the Policy Process; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Pooley, C. Walking spaces: Changing pedestrian practices in Britain since c. 1850. J. Transp. Hist. 2021, 42, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucher, J.; Buehler, R.; Seinen, M. Bicycling renaissance in North America? An update and re-appraisal of cycling trends and policies. Transp. Res. A Policy Pract. 2011, 45, 451–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, C. Bike Boom: The Unexpected Resurgence of Cycling; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Balsas, C. Towards more sustainable transportation: Lessons learned from a teaching experiment. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2001, 2, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsas, C. New directions for bicycle and pedestrian planning education in the US. Plan. Pract. Res. 2002, 17, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsas, C. Sustainable transportation planning, the evolution and impact of a new academic specialization in the USA. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2015, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsas, C. Blending individual tenacity with government’s responsibility in the implementation of US non-motorized transportation planning (NMT). Plan. Pract. Res. 2017, 32, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golub, A.; Hoffmann, M.; Lugo, A.; Sandoval, G. Bicycle Justice and Urban Transformation; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Handy, S. Shifting Gears: Toward a New Way of Thinking About Transportation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Litman, T. New Mobilities: Smart Planning for Emerging Transportation Technologies; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Delbosc, A.; Thigpen, C. Who uses subsidized micromobility, and why? Understanding low-income riders in three countries. J. Cycl. Micromobil. Res. 2024, 2, 100016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornat, J. Biographical methods. In The Sage Handbook of Social Research Methods; Alasuutari, P., Bickman, L., Brannen, J., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2008; pp. 344–356. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H. Autoethnography as Method; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, K. Cities and Complexity—Making Intergovernmental Decisions; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.; Stirling, A.; Berkhout, A. The governance of sustainable socio-technical transitions. Res. Policy 2005, 34, 1491–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. Diffusion of Innovations, 3rd ed.; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Geerlings, H.; Shiftan, Y.; Stead, D. (Eds.) Transition Towards Sustainable Mobility: The Role of Instruments, Individuals and Institutions; Ashgate Publishing: Surrey, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, J.M. Strategic Planning for Public and Nonprofit Organizations: A Guide to Strengthening and Sustaining Organizational Achievement, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Klosterman, R. Planning in the information age. In The Practice of Local Government Planning; Hoch, C., Dalton, L., So, F., Eds.; IACM: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; pp. 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Slotterback, C.S.; Lauria, M. Building a foundation for public engagement in planning: 50 years of impact, interpretation, and inspiration from Arnstein’s Ladder. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 2019, 85, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W.; Kemp, R.; Dudley, G.; Lyons, G.G. Automobility in Transition? A Socio-Technical Analysis of Sustainable Transport; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pucher, J.; Clorer, S. Taming the automobile in Germany. Transp. Q. 1992, 46, 383–395. [Google Scholar]

- Forester, J. Effective Cycling; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Forester, J. Ideas in motion: The bicycle transportation controversy. Transp. Q. 1992, 55, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- FHWA. The National Bicycling and Walking Study: Transportation Choices for a Changing American; Federal Highway Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 1994.

- Jacobs, A.B. Great Streets; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- GEIPOT. Manual de Planejamento Cicloviário; GEIPOT: Brasília, Brazil, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, A.C.M.; Xavier, G.N.A. The Brazilian Scenario for Bicycle Mobility is Changing. In Proceedings of the VeloCity Conference, Munich, Germany, 12–15 June 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T.; Novo de Azevedo, L. Economic, social and cultural transformation and the role of the bicycle in Brazil. J. Transp. Geogr. 2013, 30, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maricato, E. Fighting for just cities in capitalism’s periphery. In Searching for the Just City—Debates in Urban Theory and Practice; Marcuse, P., Connolly, N.J., Olivo, I., Potter, C., Steil, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 194–214. [Google Scholar]

- Xavier, G.N.A. O cicloativismo no Brasil e a produção da lei de política nacional de mobilidade urbana. Em TESE 2007, 3, 122–145. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcellos, E.A. Urban Transport Environment and Equity: The Case for Developing Countries, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gertten, F. Bikes vs Cars—DVD Documentary; Alive Mind: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, A.C.M. Condicionantes da Escolha da Bicicleta como Modal de Transporte nos Deslocamentos em Áreas Urbanas: Desafios e Possibilidades. MEST Dissertação Programa de Pós-Graduação em Tecnologia e Sociedade. 2022. Available online: https://repositorio.utfpr.edu.br/jspui/handle/1/31390 (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Corais, F.; Bandeira, M.; Silva, C.; Bragança, L. Between the unstoppable and the feasible: The lucid pragmatism of transition processes for sustainable urban mobility: A literature review. Fut. Transp. 2022, 2, 86–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, L.D.; Zapata, M. Engaging the Future: Forecasts, Scenarios, Plans, and Projects; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Holling, C. Understanding the complexity of economic, ecological, and social systems. Ecosystems 2001, 4, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W.; Schot, J. Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Res. Policy 2007, 36, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badami, M.G. Urban transport policy as if people and the environment mattered: Pedestrian accessibility the first step. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 2009, 44, 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, A. Reconstructing Powerful Knowledge in an era of climate change. Rev. Prod. Desenvolv. 2020, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahle, K. When do transformative initiatives really transform? A typology of different paths for transition to a sustainable society. Futures 2007, 39, 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Technological Transitions and System Innovations: A Co-Evolutionary and Socio-Technical Analysis; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, M. Cycling and transitions theories: A conceptual framework to assess the relationship between cycling innovations and sustainability goals. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2022, 15, 100642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsas, C.J. Walkable Cities: Revitalization, Vibrancy, and Sustainable Consumption; SUNY Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Balsas, C.J.L. Urbanismo Sustentável: Medidas Para Uma ‘Política de Ciclismo Urbano’; Editora CRV: Curitiba, Brazil, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Piatkowski, D. Bicycle City: Riding the Bike Boom to a Brighter Future; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Balsas, C.J. O português sou eu! Reflections on a Career Path (thus Far). Port. Stud. Rev. 2019, 27, 277–297. [Google Scholar]

- Papatsiba, V. Making higher education more European through student mobility? Revisiting EU initiatives in the context of the Bologna Process. Comp. Edu. 2006, 42, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiderman, C.; Anders, R. Best practice in pedestrian facility design: Cambridge, Massachusetts. In Sustainable Transport—Planning for Walking and Cycling in Urban Environments; Tolley, R., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003; pp. 619–628. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, K.; Washington, S.P.; Schalkwyk, I.V. Evaluation of the Scottsdale Loop 101 automated speed enforcement demonstration program. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2009, 41, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadik-Khan, J.; Solomonow, S. Streetfight: Handbook for an Urban Revolution; Penguin: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McClintock, H. The Bicycle and City Traffic: Principles and Practice; Belhaven Press: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- McClintock, H. Practitioners’ take-up of professional guidance and research findings: Planning for cycling and walking in the UK. Plan. Pract. Res. 2001, 16, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, H. Local transport plans, planning policy guidance & cycling policy: Issues & future challenges. World Transp. Pol. Pract. 2001, 7, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Tolley, R. (Ed.) Sustainable Transport: Planning for Walking and Cycling in Urban Environments; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J. The Social Logic of Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B. Space is the Machine: A Configurational Theory of Architecture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fábos, J.G.; Ahern, J. (Eds.) Greenways: The Beginning of An International Movement; Elsevier: Amsterdam, NL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.L.; Fábos, J.G.; Allan, J.J. Understanding opportunities and challenges for collaborative greenway planning in New England. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2006, 76, 172–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamu, C.; van Nes, A.; Garau, C. Bill Hillier’s Legacy: Space Syntax—A synopsis of basic concepts, measures, and empirical application. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, J.R.; Ahern, J. (Eds.) Environmental Challenges in an Expanding Urban World and the Role of Emerging Information Technologies; CNIG: Lisbon, Portugal, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, J.C.; Machado, J.R. Infra-estruturas verdes para um futuro urbano sustentável. O contributo da estrutura ecológica e dos corredores verdes. Rev. Labverde 2010, 1, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, T.; de Aguiar, F.B.; Curado, M.J. The Alto Douro wine region greenway. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2004, 68, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, A. Uma nova perspectiva de ordenamento do território para o Concelho de Coimbra. Cad. Geogr. 2004, 21, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Toccolini, A.; Fumagalli, N.; Senes, G. Greenways planning in Italy: The Lambro River Valley greenways system. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2006, 76, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fábos, J.G.; Ryan, R.L. An introduction to greenway planning around the world. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2006, 76, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, J.H. Asphalt Nation: How the Automobile Took over America and How We Can Take It Back; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, C.W. Car Country: An Environmental History; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, P. Road to Nowhere: What Silicon Valley Gets Wrong About the Future of Transportation; Verso Books: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmento, J. Driving through car geographies. Aurora Geogr. J. 2007, 1, 83–107. [Google Scholar]

- Soliz, A.; Carvalho, T.; Sarmiento-Casas, C.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, J.; El-Geneidy, A. Scaling up active transportation across North America: A comparative content analysis of policies through a social equity framework. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2023, 176, 103788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, P.A. Portugal a Pedalar—José Manuel Caetano; Leituria and FPCUB: Lisbon, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ellin, N. Canalscape: Practising integral urbanism in metropolitan Phoenix. J. Urb. Des. 2010, 15, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAslan, D.; Buckman, S. Water and Asphalt: The impact of canals and streets on the development of Phoenix, Arizona, and the erosion of modernist planning. J. Southw. 2019, 61, 658–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smardon, R.; Moran, S.; Baptiste, A.K. Revitalizing Urban Waterway Communities: Streams of Environmental Justice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schimek, P. The Dilemmas of Bicycle Planning. In Proceedings of the Joint 1996 ACSP-AESOP Conference, Toronto, ON, Canada, 27 July 1996; Available online: https://www.transcyclist.net/dmink/bike/info/dilemma.htm (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Linovski, O. Politics of expertise: Constructing professional design knowledge in the public and private sectors. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2016, 36, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossoff, G. Holism and the reconstitution of everyday life: A framework for transition to a sustainable society. Design Philos. Pap. 2015, 13, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, E.; Hult, A. The travelling business of sustainable urbanism: International consultants as norm-setters. Environ. Plan. A 2017, 49, 1779–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.G.; Ward, K. Urban policy mobilities: Recent debates and future research agendas. Geogr. Rev. 2024, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, N.M. The End of the Car City in Portugal. In Urban Change in the Iberian Peninsula: A 2000–2030 Perspective; Lois-González, R.C., Rio Fernandes, J.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 265–273. [Google Scholar]

- Mota, J.C.; Sá, F.M.E.; Isidoro, C.; Pereira, B.C. Bike-Friendly Campus, new paths towards sustainable development. In Higher Education and Sustainability—Opportunities and Challenges for Achieving Sustainable Development Goals; Azeiteiro, U., Davim, J.P., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; pp. 223–245. [Google Scholar]

- Searns, R. Beyond Greenways: The Next Step for City Trails and Walking Routes; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, P.; Dender, K.V. ‘Peak car’—Themes and issues. Transp. Rev. 2013, 33, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, P.; Abouarghoub, W.; Pettit, S.; Beresford, A. A socio-technical transitions perspective for assessing future sustainability following the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2020, 16, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Homrighausen, J.R.; Tan, W.G.Z. Institutional innovations for sustainable mobility: Comparing Groningen (NL) and Phoenix (US). Transp. Res. Proc. 2016, 19, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pileri, P.; Moscarelli, R. (Eds.) Cycling & Walking for Regional Development: How Slowness Regenerates Marginal Areas; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, P. Walking & Cycling—Uma Nova Geografia Do Turismo; Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmento, J.C.V. The geography of “disused” railways: What is happening in Portugal? Finisterra 2002, 37, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, T. Urban ecology: Green networks and ecological design. In Sustainability for the 21st Century: Pathways Programs and Policies; Pijawka, D., Ed.; Kendall Hunt Publishing: Dubuque, IA, USA, 2015; pp. 111–136. [Google Scholar]

- Samples, S. Bridging the Divide: Why Landscape Architects Should Start Preaching to the Choir. Ph.D. Thesis, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cervero, R.; Guerra, E.; Al, S. Beyond Mobility: Planning Cities for People and Places; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Broto, V.C.; Coenen, L.; Loorbach, D. (Eds.) Urban Sustainability Transitions; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Buttigieg, P. Shortest Way Home: One Mayor’s Challenge and a Model for America’s Future; Liveright Publishing Corporation: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tudor-Locke, C. Walk more (frequently, farther, faster)—The perfect preventive medicine. Prev. Med. 2012, 55, 540–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appleyard, B.; Appleyard, D. Livable Streets 2.0; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Honey-Rosés, J. Rethinking public space and urban mobility. J. Am. Plann, Assoc. 2025, 91, 638–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temenos, C.; Nikolaeva, A.; Cresswell, T.; Sengers, F.; Sheller, M.; Schwanen, T.; Watson, M. Theorizing Mobility Transitions: An interdisciplinary conversation. Transf. Int. J. Mob. Stud. 2017, 7, 113–129. [Google Scholar]

- Balsas, C. Enthralling prefigurative urban and regional planning forward. Land 2023, 12, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Kenworthy, J.; Marinova, D. Higher density environments and the critical role of city streets as public open spaces. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquet, O.; Anguelovski, I.; Nello-Deakin, S.; Honey-Rosés, J. Decoding the 15-Minute City Debate: Conspiracies, backlash, and dissent in planning for proximity. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 2025, 91, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Low Means Low Ends | Low Means High Ends | High Means Low Ends | High Means High Ends | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal | Period in Portugal before Erasmus study abroad (growth of household incomes, motorizing nation) | Aveiro (political leadership, Bicicleta de Utilização Gratuita de Aveiro/Aveiro’s Free Use Bicycle—BUGA), late 1990s and early to mid-2000s | Phoenix growth model (low ends due to more of the same automobility models) | Global Financial Crisis—inversion of VMT (car-peak) 2012–2013 |

| Academia | Teaching transportation (in the 1990s) without considering NMT | McClintock’s online bicycle encyclopaedia | Armchair theorizing without ample real applications | Academic legacy and rich databases of studies |

| Institutional realm | Status quo is dominated by generalized high levels of automobility | U.S. National Bicycling and Walking Study; Association of Pedestrian and Bicycle Professionals (APBP) | Updating ITE’s manuals | State and local bicycle coordinators |

| Volunteering sector | Cyclo-tourism (NGO of national utility status); cyclo-tourism 1990s | Bicycle riding workshops, Phoenix’s Pedestrian Freeway | Awards/funds given to mobility public work projects that mostly foster an automobility agenda | Pulling together by different constituencies (time commitments, lobbying activities, fundraising) |

| Private realm | First generation of bike master plans produced by sustainable mobility consultants | Tactical urbanism (low tech—chalk on pavement, and straw bale for parklets, etc.) | Consultant delivered turn-key solutions without an understanding of local contexts | Design of shared bicycle schemes (learning from bicycle planning in Aveiro, Portugal) |

| Ensuing scenarios | Chaotic transition | Managed degrowth | Business as usual | Managed transition |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Balsas, C.J.L. Innovations in Non-Motorized Transportation (NMT) Knowledge Creation and Diffusion. World 2025, 6, 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6040136

Balsas CJL. Innovations in Non-Motorized Transportation (NMT) Knowledge Creation and Diffusion. World. 2025; 6(4):136. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6040136

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalsas, Carlos J. L. 2025. "Innovations in Non-Motorized Transportation (NMT) Knowledge Creation and Diffusion" World 6, no. 4: 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6040136

APA StyleBalsas, C. J. L. (2025). Innovations in Non-Motorized Transportation (NMT) Knowledge Creation and Diffusion. World, 6(4), 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6040136