Understanding Deep-Seated Paradigms of Unsustainability to Address Global Challenges: A Pathway to Transformative Education for Sustainability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Participant Selection

2.2. Data Collection Procedures

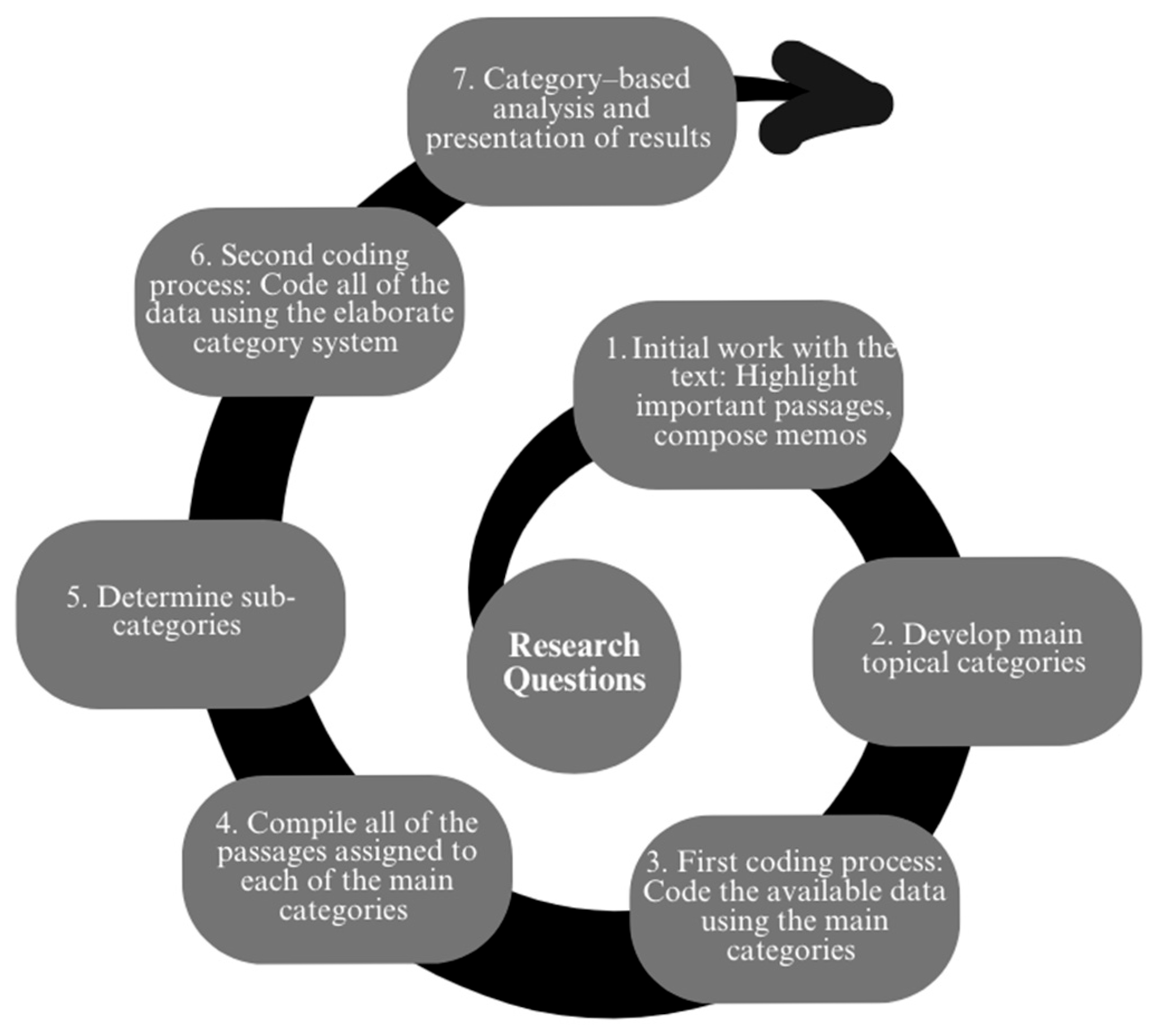

2.3. Data Analysis: Thematic Analysis

2.4. Triangulation and Data Validation

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Coding and Thematic Categorization

3.2. Rationale of Thematic Categorization

3.3. Cross-Referencing Expert Views and Literature

3.4. The Relationship Between Unsustainability Factors and the Role of Education

4. Discussion

4.1. Unraveling Root Causes of Unsustainability

4.1.1. Wholeness and Existential Crisis

4.1.2. Disconnection from Nature and Anthropocentric Perspective

4.1.3. Growth-Based Political Economy System

4.2. Global Initiatives on Education for Sustainability

4.3. Research Implication: A Pathway to Transformative Education for Sustainability

4.3.1. Addressing Wholeness Crisis Through Holistic and Value-Based Education

4.3.2. Moving Beyond Anthropocentrism Through Ecoliteracy and Ecopedagogy

4.3.3. Expanding Political-Economic Horizons Through Postgrowth Literacy

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ghosh, E.; Pearson, L.J. Rethinking Economic Foundations for Sustainable Development: A Comprehensive Assessment of Six Economic Paradigms Against the SDGs. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. World Health Statistics 2024: Monitoring Health for the SDGs; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- OPHI; UNDP. Global Multidimensional Poverty Index 2024: Poverty Amid Conflict; United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI), University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024; FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO: Rome, Italy, 2024; ISBN 978-92-5-138882-2. [Google Scholar]

- FSIN; GNAFC. 2025 Global Report on Food Crises; Food Security Information Network; Global Network Against Food Crises: Rome, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- IFBES. The Global Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; Brondízio, E.S., Settele, J., Díaz, S., Ngo, H.T., Eds.; Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES): Bonn, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3-947851-20-1. [Google Scholar]

- WWF. Living Planet Report 2024—A System in Peril; WWF International: Gland, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Benton, T.G.; Bieg, C.; Harwatt, H.; Pudasaini, R.; Wellesley, L. Food System Impacts on Biodiversity Loss; Chatham House: British, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Ecosystem Restoration for People, Nature and Climate: Becoming #GenerationRestoration; United Nations: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021; ISBN 978-92-807-3864-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kopnina, H.; Hughes, A.C.; Zhang, R.; Russell, M.; Fellinger, E.; Smith, S.M.; Tickner, L. Business Education and Its Paradoxes: Linking Business and Biodiversity through Critical Pedagogy Curriculum. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2024, 50, 2712–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Grewatsch, S.; Sharma, G. How COVID-19 Informs Business Sustainability Research: It’s Time for a Systems Perspective. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 602–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Ibrahim, R.L.; Raimi, L.; Omokanmi, O.J.; S Senathirajah, A.R.B. Balancing Growth and Sustainability: Can Green Innovation Curb the Ecological Impact of Resource-Rich Economies? Sustainability 2025, 17, 4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC (Ed.) Emissions Trends and Drivers. In Climate Change 2022—Mitigation of Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; pp. 215–294. ISBN 978-1-009-15792-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Z.; Zhang, B.; Cary, M. Linking Economic Globalization, Economic Growth, Financial Development, and Ecological Footprint: Evidence from Symmetric and Asymmetric ARDL. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 107060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabaix, X.; Laibson, D. Myopia and Discounting; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; p. w23254. [Google Scholar]

- Mella, P.; Pellicelli, M. How Myopia Archetypes Lead to Non-Sustainability. Sustainability 2017, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høyer, K.G.; Næss, P. The Ecological Traces of Growth: Economic Growth, Liberalization, Increased Consumption—And Sustainable Urban Development? J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2001, 3, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlek, C.; Steg, L. Human Behavior and Environmental Sustainability: Problems, Driving Forces, and Research Topics. J. Soc. Issues 2007, 63, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onel, N.; Mukherjee, A. The Effects of National Culture and Human Development on Environmental Health. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2014, 16, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgin, D. Building a Sustainable Species-Civilization. Futures 1994, 26, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Akura, G. Addressing the Wicked Problems of Sustainability Through Consciousness-Based Education. J. Health Environ. Res. 2017, 4, 75–124. [Google Scholar]

- Csillag, S.; Király, G.; Rakovics, M.; Géring, Z. Agents for Sustainable Futures? The (Unfulfilled) Promise of Sustainability at Leading Business Schools. Futures 2022, 144, 103044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snelson-Powell, A.C.; Grosvold, J.; Millington, A.I. Organizational Hypocrisy in Business Schools with Sustainability Commitments: The Drivers of Talk-Action Inconsistency. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 114, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H. Education for Sustainable Development Goals (ESDG): What Is Wrong with ESDGs, and What Can We Do Better? Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.; Kulshreshtha, A.K. A Study of Environmental Value and Attitude Towards Sustainable Development among Pupil Teachers. OIDA Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 3, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4522-5787-7. [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden, V.L.; Peterson, R.A. Ruminations about Making a Theoretical Contribution. AMS Rev. 2011, 1, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, R.M. Knowledge from Knowledge: An Essay on Inferential Knowledge. Ph.D. Thesis, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, New Jersey, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gläser, J.; Laudel, G. On Interviewing “Good” and “Bad” Experts. In Interviewing Experts; Gläser, J., Laudel, G., Eds.; Research methods, series; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-0-230-22019-5. [Google Scholar]

- Meuser, M.; Nagel, U. The Expert Interview and Changes in Knowledge Production. In Interviewing Experts; Bogner, A., Littig, B., Menz, W., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009; pp. 17–42. ISBN 978-1-349-30575-9. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough?: An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogner, A.; Littig, B.; Menz, W. The Theory-Generating Expert Interview: Epistemological Interest, Forms of Knowledge, Interaction. In Interviewing Experts; Bogner, A., Menz, W., Eds.; Research methods, series; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-0-230-22019-5. [Google Scholar]

- Witzel, A. The Problem-Centered Interview. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2000, 1, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Bogner, A.; Littig, B.; Menz, W. Between Scientific Standards and Claims to Efficiency: Expert Interviews in Programme Evaluation. In Interviewing Experts; Wroblewski, A., Leitner, A., Eds.; Research methods, series; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-0-230-22019-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kuckartz, U. Qualitative Text Analysis: A Guide to Methods, Practice & Using Software; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4462-6775-2. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 2nd ed.; [Nachdr.]; Sage Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-7619-1544-7. [Google Scholar]

- Albig, W. Content Analysis in Communication Research. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 1952, 283, 197–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, K.; Bazeley, P. Qualitative Data Analysis with NVivo, 3rd ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA; London, UK; New Delhi, India; Singapore; Washington, DC, USA; Melbourne, Australia, 2019; ISBN 978-1-5264-4993-1. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 2nd ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4462-4736-5. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research, 5th ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4462-6778-3. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Miller, D.L. Determining Validity in Qualitative Inquiry. Theory Pract. 2000, 39, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew Hung, C. Climate Change Education: Knowing, Doing and Being, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; ISBN 978-1-003-09380-0. [Google Scholar]

- Titumir, R.A.M.; Afrin, T.; Islam, M.S. Natural Resource Degradation and Human-Nature Wellbeing: Cases of Biodiversity Resources, Water Resources, and Climate Change; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; ISBN 978-981-19-8660-4. [Google Scholar]

- Thunberg, G. The Climate Book; Penguin Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Santelices Spikin, A.; Rojas Hernández, J. Climate Change in Latin America: Inequality, Conflict, and Social Movements of Adaptation. Lat. Am. Perspect. 2016, 43, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muyambo, F.; Belle, J.; Nyam, Y.S.; Orimoloye, I.R. Climate Change Extreme Events and Exposure of Local Communities to Water Scarcity: A Case Study of QwaQwa in South Africa. Environ. Hazards 2024, 23, 405–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behaviour: Reactions and Reflections. Psychol. Health 1991, 26, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, J.; Heidrich, O.; Cairns, K. Psychological Factors to Motivate Sustainable Behaviours. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.—Urban Des. Plan. 2014, 167, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, D.; Pelletier, L.G. The Roles of Motivation and Goals on Sustainable Behaviour in a Resource Dilemma: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 69, 101437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T. Prosperity Without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet; Earthscan: London, UK; Sterling, VA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-84407-894-3. [Google Scholar]

- Belk, R.W. Possessions and the Extended Self. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 139–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mella, P. Systems Thinking. In Perspectives in Business Culture; Springer: Milano, Italy, 2012; Volume 2, ISBN 978-88-470-2564-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gattig, A.; Hendrickx, L. Judgmental Discounting and Environmental Risk Perception: Dimensional Similarities, Domain Differences, and Implications for Sustainability. J. Soc. Issues 2007, 63, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattig, A. Intertemporal Decision Making: Studies on the Working of Myopia; ICS dissertation series; Rijksuniv: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2002; ISBN 978-90-5170-603-1. [Google Scholar]

- Washington, H.; Kopnina, H. Discussing the Silence and Denial around Population Growth and Its Environmental Impact. How Do We Find Ways Forward? World 2022, 3, 1009–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreskes, N.; Conway, E.M. Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming; Bloomsbury Press: New York, NY, USA; Berlin, Germany; London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kallis, G.; Kostakis, V.; Lange, S.; Muraca, B.; Paulson, S.; Schmelzer, M. Research On Degrowth. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2018, 43, 291–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, H.E. Beyond Growth: The Economics of Sustainable Development; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, C. Growth Fetish; Allen & Unwin: Sydney, Australia, 2003; ISBN 978-1-74114-078-1. [Google Scholar]

- Fromm, E. To Have or to Be? Continuum: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-0-8264-1738-1. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, J.C. Toward a Theory of Cultural Trauma. In Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity; Macmillan Education UK: London, UK, 2017; pp. 375–386. ISBN 978-1-137-61120-8. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, B.G. Sustainability: A Philosophy of Adaptive Ecosystem Management; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-226-59519-1. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J. Beyond the Limits: Confronting Global Collapse or a Sustainable Future; Chelsea Green Pub: Chelsea, VT, USA, 1992; ISBN 978-0-930031-55-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kopnina, H.; Washington, H.; Taylor, B.; J Piccolo, J. Anthropocentrism: More than Just a Misunderstood Problem. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2018, 31, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, H.; Piccolo, J.J.; Kopnina, H.; O’Leary Simpson, F. Ecological and Social Justice Should Proceed Hand-in-Hand in Conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2024, 290, 110456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, H. Growthism: Its Ecological, Economic and Ethical Limits; World Economics Association: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, S. Learning and Sustainability in Dangerous Times: The Stephen Sterling Reader, 1st ed.; Agenda Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2024; ISBN 978-1-78821-692-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, S. Learning for Resilience, or the Resilient Learner? Towards a Necessary Reconciliation in a Paradigm of Sustainable Education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 16, 511–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Broadgate, W.; Deutsch, L.; Gaffney, O.; Ludwig, C. The Trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration. Anthr. Rev. 2015, 2, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; De Vries, W.; De Wit, C.A.; et al. Planetary Boundaries: Guiding Human Development on a Changing Planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marouli, C. Sustainability Education for the Future? Challenges and Implications for Education and Pedagogy in the 21st Century. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanaček, K.; Roy, B.; Avila, S.; Kallis, G. Ecological Economics and Degrowth: Proposing a Future Research Agenda from the Margins. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 169, 106495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H. Education for Sustainable Development (ESD): The Turn Away from ‘Environment’ in Environmental Education? Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 699–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kann, M.E. Political Education and Equality: Gramsci Against “False Consciousness”. Teach. Polit. Sci. 1981, 8, 417–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D. Neoliberalism, Class, ‘Race’; The Institute for Education Policy Studies: Brighton, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-0-9522042-2-0. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera Maulucci, M.S.; Pfirman, S.; Callahan, H.S. Transforming Education for Sustainability: Discourses on Justice, Inclusion, and Authenticity. In Environmental Discourses in Science Education; Rivera Maulucci, M.S., Pfirman, S., Callahan, H.S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 7, ISBN 978-3-031-13535-4. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, K. The Relationship between Academic Performance and Environmental Sustainability Consciousness: A Case Study in Higher Education. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2021, 12, 2168–2176. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, R.D.; Hackler, D. Economic Doctrines and Approaches to Climate Change Policy; ITIF: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mattauch, L.; Hepburn, C. Climate Policy When Preferences Are Endogenous-and Sometimes They Are. Midwest Stud. Philos. 2016, 40, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, J.D.; Hepburn, C.; Mealy, P.; Teytelboym, A. A Third Wave in the Economics of Climate Change. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2015, 62, 329–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villavicencio Calzadilla, P. The Sustainable Development Goals, Climate Crisis and Sustained Injustices. Oñati Socio-Leg. Ser. 2021, 11, 285–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capra, F. The Systems View of Life, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; ISBN 978-1-003-02071-4. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.T.P. From Shame to Wholeness an Existential Positive Psychology Perspective; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.T.P. Existential Positive Psychology. Int. J. Existent. Psychol. Psychother. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, P.J. A Hidden Wholeness: The Journey Toward an Undivided Life: Welcoming the Soul and Weaving Community in a Wounded World; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mulalić, M. The Spirituality and Wholeness in Education. J. Hist. Cult. Art Res. 2017, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirley, D. Beyond Well-Being: The Quest for Wholeness and Purpose in Education. ECNU Rev. Educ. 2020, 3, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowdy, J.M. Hunter Gatherers and the Crisis of Civilization. In Annals of the Fondazione Luigi Einaudi: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Economics, History and Political Science: LV 1; Leo S. Olschki: Florence, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschle, J. “Secularization of Consciousness” or Alternative Opportunities? The Impact of Economic Growth on Religious Belief and Practice in 13 European Countries. J. Sci. Study Relig. 2013, 52, 410–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkliarevsky, G. Living a Non-Anthropocentric Future. SSRN Electron. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, T. Anthropocentrism: A Misunderstood Problem. Environ. Values 1997, 6, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, H.; Piccolo, J.; Gomez-Baggethun, E.; Kopnina, H.; Alberro, H. The Trouble with Anthropocentric Hubris, with Examples from Conservation. Conservation 2021, 1, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; Graumlich, L.; Steffen, W.; Crumley, C.; Dearing, J.; Hibbard, K.; Leemans, R.; Redman, C.; Schimel, D. Sustainability or Collapse: What Can We Learn from Integrating the History of Humans and the Rest of Nature? AMBIO J. Hum. Environ. 2007, 36, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capra, F. The Web of Life: A New Scientific Understanding of Living Systems; Anchor Books: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, J.W. Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital; Verso: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kopnina, H. The Victims of Unsustainability: A Challenge to Sustainable Development Goals. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2016, 23, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchs, M.; Koch, M. Postgrowth and Wellbeing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; ISBN 978-3-319-59902-1. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, J.W. Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism; PM Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara, S. Living in the Age of Market Economics: An Analysis of Formal and Informal Institutions and Global Climate Change. World 2025, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.J.; Long, M.A.; Stretesky, P.B. Green Criminology and Green Theories of Justice: An Introduction to a Political Economic View of Eco-Justice; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-3-030-28572-2. [Google Scholar]

- Berchin, I.I.; De Aguiar Dutra, A.R.; Guerra, J.B.S.O.D.A. How Do Higher Education Institutions Promote Sustainable Development? A Literature Review. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žalėnienė, I.; Pereira, P. Higher Education For Sustainability: A Global Perspective. Geogr. Sustain. 2021, 2, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H.; Cocis, A. Environmental Education: Reflecting on Application of Environmental Attitudes Measuring Scale in Higher Education Students. Educ. Sci. 2017, 7, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H. Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) as if Environment Really Mattered. Environ. Dev. 2014, 12, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H.; Meijers, F. Education for Sustainable Development (ESD): Exploring Theoretical and Practical Challenges. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2014, 15, 188–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilbury, D. Whole-School-Approach to Sustainability in Schools: A Review; DG Education, Youth, Sport and Culture: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fien, J. Learning to Care: Education and Compassion. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2003, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, E.A. Transformative Sustainability Education: Reimagining Our Future, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; ISBN 978-1-003-15964-3. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudi, S.; Jafari, E.; Nasrabadi, H.A.; Liaghatdar, M.J. Holistic Education: An Approach for 21 Century. Int. Educ. Stud. 2012, 5, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.P. The Holistic Curriculum, 3rd ed.; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada; Buffalo, NY, USA; London, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-4875-0413-7. [Google Scholar]

- Lauricella, S.; MacAskill, S. Exploring the Potential Benefits of Holistic Education: A Formative Analysis. J. Educ. Altern. 2015, 4, 54–78. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, J.H.; Rands, P.; Scoffham, S. Leadership for Sustainability in Higher Education; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, E.M. Justice and Equity in Climate Change Education: Exploring Social and Ethical Dimensions of Environmental Education, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-0-429-32601-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hupkes, T.; Hedman, A. Shifting Towards Non-Anthropocentrism: In Dialogue with Speculative Design Futures. Futures 2022, 140, 102950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradidge, S.; Zawisza, M. Toward a Non-Anthropocentric View on the Environment and Animal Welfare: Possible Psychological Interventions. Anim. Sentience 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Motos, D. Ecophilosophical Principles for an Ecocentric Environmental Education. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckersley, R. Environmentalism and Political Theory: Toward an Ecocentric Approach, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; ISBN 978-1-315-07211-1. [Google Scholar]

- Naess, A. The Shallow and the Deep, Long-range Ecology Movement. A Summary. Inquiry 1973, 16, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaChapelle, D. Educating for Deep Ecology. J. Exp. Educ. 1991, 14, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, D.W. Ecological Literacy: Education and the Transition to a Postmodern World; State University of New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kopnina, H.; Black, K.; Tracey, H. Ecoliteracy and Ecopedagogy for Environmental Sustainability in Education. Vis. Sustain. 2024, 22, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D. The Age of Sustainable Development; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-231-17315-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, R. From Education for Sustainable Development to Ecopedagogy: Sustaining Capitalism or Sustaining Life? Green Theory Prax. J. Ecopedagogy 2008, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, R. Critical Pedagogy, Ecoliteracy & Planetary Crisis: The Ecopedagogy Movement. Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 17, 705–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, H. Post-Anthropocentric Pedagogies: Purposes, Practices, and Insights for Higher Education. Teach. High. Educ. 2025, 30, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, H.E. Steady-State Economics: Second Edition with New Essays; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1991; ISBN 1-55963-072-8. [Google Scholar]

- Coyle, D. The Economics of Enough: How to Run the Economy as if the Future Matters; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Raworth, K. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist; Chelsea Green Publishing: Junction, VT, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R. Ecological Economics 1; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hickel, J. Less Is More How Degrowth Will Save the World; William Heinemann: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- White, R.J. Imagining Education beyond Growth: A Post-Qualitative Inquiry into the Educational Consequences of Post-Growth Economic Thought. Curric. Perspect. 2024, 44, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caradonna, J.L. Sustainability: A History; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0-19-937240-9. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J.; Behrens Ill, W.W. Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind; Universe Books: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- McNamara, K.R. Of Intellectual Monocultures and the Study of IPE. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 2009, 16, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Experts | Area of Expertise | Sector of Engagement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academia/ Educational Institution | Business Practice | Environmental/ Sustainability Issues | NGOs /International Agencies | Policy Making | ||

| 1 | Expert 1 | √ | √ | √ | ||

| 2 | Expert 2 | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| 3 | Expert 3 | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| 4 | Expert 4 | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| 5 | Expert 5 | √ | √ | √ | ||

| 6 | Expert 6 | √ | √ | √ | ||

| 7 | Expert 7 | √ | √ | √ | ||

| 8 | Expert 8 | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Code | Code Description | Data Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Greedy | Description: the insatiable desire for more, driven by inner emptiness, leading to excessive accumulation of material goods. | “We have this culture of never having enough.” “We never feel contented with what we have. If we have three cars, we want four.” “I cannot feel satisfied with what I have because of inner emptiness.” |

| Inclusion Criteria: Involves the desire for more than necessary, focusing on endless accumulation, refusal to accept limits, and inability to be content with what one has. | ||

| Exclusion Criteria: Excludes consumption driven by basic needs or external circumstances. |

| Experts | INF = INF 1 (1) | INF = INF 2 (1) | INF = INF 3 (1) | INF = INF 4 (1) | INF = INF 5 (1) | INF = INF 6 (1) | INF = INF 7 (1) | INF = INF 8 (1) | Total (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unsustainability | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1. Events | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 | Social Inequity | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| 2 | Pollution and Waste Accumulation | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| 3 | Overshooting Planetary Limits | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| 4 | Natural Resource Depletion | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| 5 | Geopolitical Tension | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| 6 | Economic Instability | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| 7 | Disaster | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| 8 | Climate Change | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| 2. Behavior | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 9 | Dissatisfaction | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 10 | Unemphatic | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 11 | Materialism | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| 12 | Lifestyle | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 13 | Individualism | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 14 | Consumerism | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| 15 | Consume the future | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 16 | Competitiveness | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 3. Underlying factors | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 17 | Weak Legal Enforcement | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 18 | Trade-off Thinking | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 19 | Short-termism | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 20 | Myopia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 21 | Growthism | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 22 | Greedy | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| 23 | Denial | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 24 | Collective Trauma | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 4. Systemic paradigm | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 25 | Limited Human Consciousness | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 26 | Ideological-Based Political Economy | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| 27 | Disconnected from Nature | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Total (unique) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | |

| Expert | RQ3: The Role of Education |

|---|---|

| Expert 1 | Education must shift from reinforcing outdated economic paradigms like competition and growth. It should integrate systemic thinking, ecological awareness, and personal responsibility, helping students understand their impact on the environment and society. Most education today, however, continues to teach the same thinking that has created the problem. |

| Expert 2 | Education should instill values and ethics that encourage students to engage with sustainability at every level. It must educate students in the way that sustainability intersects every dimension of life from social justice to ecological equilibrium and encourage in them the ability to critique practices that are not sustainable. But education tends to divorce values from science and technology, deepening the crisis of meaning. |

| Expert 3 | Education must be focused on behavioral change and values development, encouraging students to not only understand sustainability but to live by its principles. It needs to cater for personal attitudes, values and long-term environmental responsibility in the context of both academic and personal development. For environmental education is a point of entry to the perception that we are part of the environment. |

| Expert 4 | Education should be a reflection of real-life sustainable action, a practice that promotes not only student understanding but also student efforts in sustainable action. This includes promoting behaviors that are consistent with ecological and other kinds of social values, both individually and organizationally. |

| Expert 5 | Education should not just be an academic exercise. It should be practical, hands-on experiences that make sustainability real. Field trips and hands-on-approaches to sustainability give students a better sense of how their place in the world is impacted by what they do. |

| Expert 6 | Education should be reformed to integrate sustainability across all business sectors. It must challenge students to rethink business practices, with a focus on social equity, ecological responsibility, and sustainable consumption, preparing them to address systemic issues in business. Current education, however, often hides the truth, leading to false consciousness about sustainability. |

| Expert 7 | Education should foster values and critical thinking, helping students move beyond knowledge to behavior change. It must prepare them for the complex, interconnected challenges of sustainability, emphasizing real-world applications that align social, environmental, and economic goals. |

| Expert 8 | Education should be all about behavioral change; giving students the skills they need to be able to live sustainably, teaching respect for the natural environment and consequences of their actions in the long run. It includes encouraging moderation, daily sustainability and intergenerational justice as well as wisdom and knowledge in recognizing borders. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dewi, D.E.; Winoto, J.; Achsani, N.A.; Suprehatin, S. Understanding Deep-Seated Paradigms of Unsustainability to Address Global Challenges: A Pathway to Transformative Education for Sustainability. World 2025, 6, 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030106

Dewi DE, Winoto J, Achsani NA, Suprehatin S. Understanding Deep-Seated Paradigms of Unsustainability to Address Global Challenges: A Pathway to Transformative Education for Sustainability. World. 2025; 6(3):106. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030106

Chicago/Turabian StyleDewi, Desi Elvera, Joyo Winoto, Noer Azam Achsani, and Suprehatin Suprehatin. 2025. "Understanding Deep-Seated Paradigms of Unsustainability to Address Global Challenges: A Pathway to Transformative Education for Sustainability" World 6, no. 3: 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030106

APA StyleDewi, D. E., Winoto, J., Achsani, N. A., & Suprehatin, S. (2025). Understanding Deep-Seated Paradigms of Unsustainability to Address Global Challenges: A Pathway to Transformative Education for Sustainability. World, 6(3), 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030106