1. Introduction

This research proposes to analyze the discourses commonly constructed around the tourism platform economy of a large tourist-driven city, in this case Madrid. Notably, our focus is not the socioeconomic and/or geographical processes prompted by tourism within platform capitalism; rather, we consider how those processes are discussed, as well as the discursive competition between diverse speakers and the power relations revealed by such competition. In this context, we focus on who is saying what, how, and the goals of that discourse. This study is situated within urban discourse analysis—a relatively recent area in the social sciences that has yielded significant insights [

1,

2].

This research does not draw an epistemological boundary between the geographical impacts of the platform economy and the discourses it examines. Instead, it adopts a social constructivist approach, based on the premise that material and social realities are not external to discourse, but are shaped through it. From this view, discourses do not simply mirror reality—they play an active role in its (re)construction, through a dynamic, two-way relationship in which meaning and materiality are mutually constitutive [

3]. Constructing narratives around these processes involves ‘things being done’—taking a performative stance that influences reality through the knowledge, imagination, and actions of the actors involved. In this sense, even if material and social spaces are the focus, discourses can also be seen as ‘places’ where social, economic, and spatial relations are produced and reproduced through conflict. Discourses, then, are not neutral or objective descriptions of events, nor just personal perceptions. Rather, they are intentional acts, embedded with the power relations already present in society [

3]. Moreover, discourses have the capacity to influence the actions of social actors, and therefore, the decisions and policies implemented in a given city or concerning specific aspects of urban social life [

4].

A particularly striking feature of the platform economy, when viewed through a discourse-oriented lens, is the lack of consensus around normative definitions that might clarify this supposedly new economic model [

5,

6,

7], or its perceived economic, social, and spatial effects [

7,

8]. There remains significant variation—even in basic terminology. The most common terms in the literature are ‘platform economy’ and ‘collaborative economy’, but others include ‘gig economy’, ‘on-demand economy’, ‘peer-to-peer economy’ (P2P), and ‘collaborative consumption’ [

5,

6], along with 17 distinct terms identified by Dredge and Gyimóthy [

9]. Though these labels describe the same phenomenon, each emphasizes different elements, reflecting both the interaction between economic and social activity [

7] and ongoing efforts to highlight or obscure specific dimensions. This study adopts the term ‘platform economy’, which draws attention to the technological mediation central to these models. Still, it is important to note that ‘platform’ goes beyond digital interfaces to describe a business model structured around large-scale data organization and specific forms of governance and data management [

10,

11].

Although the term ‘collaborative economy’ is equally widespread, we argue that framing collaboration as a disruptive force—as is often the case in more favorable accounts—overlooks the longstanding, everyday forms of cooperation found in cohesive working-class and low-income communities. The only genuinely novel aspect is the facilitation of collaboration between strangers [

7,

9,

12]. Moreover, while early platforms like Couchsurfing prioritized non-monetary exchanges, the field has since been overtaken by platforms driven primarily by profit rather than by mutual aid among equals [

5]—including those now reshaping the tourism sector, which is our focus. As Schor [

7] notes, the concept of a collaborative economy is itself a discursive construct shaped by neoliberal economic logic, which in turn fuels its further development. In this sense, the term does not just describe a set of practices—it also helps to justify, produce, and stabilize them [

5,

7].

Discourses specifically addressing tourism platforms largely mirror the broader ‘pro’ and ‘con’ narratives associated with the platform economy, albeit with sector-specific nuances. What becomes clear is that the tone of these discourses—whether positive or negative—depends entirely on the speaker’s position within the tourism platform ecosystem, whether as provider, client, or member of the host community. Notably, it is often the latter group—those embedded in the host setting—who are most adversely affected by tourism-related practices [

8].

The advantages defended by diverse narratives within the touristic context tend toward economic aspects, including increased offer, lower costs that benefit consumers [

8,

13], and the possible actualization of underutilized resources [

14], permitting their owners to become mini entrepreneurs [

9]. Potential benefits are also cited for the sustainability of the sector, although doubts persist around such claims, with projections of ongoing exacerbation of neoliberalism’s most negative expressions [

13].

On the contrary, negative discourses point mainly to increases in unemployment due to competition with the traditional tourism sector, which receives neither quantitative nor qualitative compensation from the ‘casualized’ jobs created through this new supply modality [

8,

13,

15]. Also noted is a loss of quality in urban life due to the deterioration of social cohesion and community rights, whether individual or collective, which ultimately leads to conflicts between residents and tourists and other problems related to urban security [

13].

While the transformation of social, economic, and labor relations must all be taken into account, so must the impacts on space itself, as illustrated in the case of the touristified city. At odds with the global nature of large companies and their aura of immateriality is the fact that they are driving large-scale activity concentrated into specific urban spaces that offer the material and demographic density required to make their financial logic profitable. As Shaw [

16] indicates, the ‘platformization’ of society has built its prototype within the urban space, and the city has been its primary site of experimentation.

Beyond platforms offering goods (such as Amazon), or advertising and social media (Facebook), or infrastructure for digital communications (Google), the connection between urban logic and platform logic is especially significant in the case of what are known as ‘lean companies’—enterprises without the assets or workforce necessary to produce the services they intermediate [

11]. These would include the cases of Uber, Airbnb, and practically all platforms focused on mobility, tourism, leisure, and delivery. Mediating between consumers and the ‘independent contractors’ who provide the labor force and necessary goods, the lean platform outsources most of its costs and retains few assets (apart from those required to maintain and manage itself) [

10].

As Strüver and Baurield [

11] note, the expansion of such lean platforms has produced huge impacts (both short- and long-term) on the urban economy and its social relations, prompting changes to consumption patterns, infrastructures, and working conditions. These impacts have caused a general “platformization of urban life” [

11] (p. 13) and affect urban society as a whole, even for those who ignore such services or whose direct social, economic, and labor relations are not affected.

As Richardson has remarked [

17], platforms have no fixed territory, but they draw on territorialized networks and, by doing so, alter the urban form. Thus, rather than producing a spatial pattern of their own, they reconfigure existing patterns and generate new spatialities [

18]. This entails the integration of spaces and bodies into a network of new interrelations, transforming the materiality of space as well as its perception and symbolism.

A key issue concerns the creation and governance of these new spatialities. Platforms use algorithms to manage and optimize user interactions and behaviors, resulting in opaque, centralized control over both data and decision-making processes. This raises serious concerns around equity, social justice, and democratic accountability. Beyond challenging existing regulatory frameworks—and deepening urban inequality—platforms also shape how urban space is lived and how alternative futures within it are imagined [

18]. In doing so, they restrict the physical and imaginative scope of the “right to the city” as envisioned by Lefebvre [

19].

Another important aspect of this business model is its emphasis on integrating and monetizing so-called ‘idle resources’ [

14]. Platforms effectively remove from democratic oversight the power to define what counts as idle, by what criteria, and for what purposes and times such resources should be used. This results in the private appropriation of assets and spaces that are public or lack clearly defined property rights [

20]. In doing so, platforms shift the use value of spaces—whether private (like housing) or public (such as shared areas in residential buildings, streets, sidewalks, urban infrastructure, or green spaces)—into exchange value. These spaces become productive assets that sustain an economic model which owns few resources itself but captures and exploits many public and private ones.

The material changes and practices associated with platform tourism at the geographical level are clearly substantial—examples include dark kitchens, the takeover of public spaces by delivery services and tourist-oriented terraces, the use of shared areas in residential buildings by guests, the occupation of housing and historic centers, and rising noise levels. Equally important, however (especially for the purposes of this study), are the symbolic transformations that reshape people’s sense of place, their emotional connection to space and scale, and particularly their perception of what is ‘local’ [

11]. While the commodification of space, community, and local culture as sellable experiences is not new to tourism, platforms like Airbnb have assumed an increasingly complex and multidimensional role within urban capitalism, constructing and marketing new spaces as if they embodied authentic reality [

21].

One of the most widespread and yet deeply rooted criticisms of the new spatialities created by the tourism platform economy concerns the shrinking supply of residential housing. The growing overlap between the real estate market and short-term rental platforms—especially in increasingly strained and financialized urban housing contexts—has widened the ‘rent gap’ [

22] between housing used for permanent residence and that redirected to tourism. This often reduces access to long-term housing in terms of affordability, location, and quality [

8,

9,

15,

23], and in some cases accelerates the displacement of long-standing residents and local businesses. As a result, a growing body of research has explored how touristification intersects with the more familiar process of gentrification, noting that while they frequently overlap, they stem from different causes and produce distinct urban outcomes [

23,

24].

Smith [

22] defines gentrification as a process of urban change marked by rising property values and the displacement of lower-income residents, driven by investment and exclusionary urban policies. In contrast, touristification refers to the reorientation of urban spaces towards the needs of tourists, frequently at the expense of local communities [

23,

24,

25]. As stated [

23], this process entails not only physical changes but also shifts in local identity, and the commodification of culture, public space, and housing, ultimately altering the community’s social fabric. While gentrification emphasizes socio-economic displacement linked to real estate dynamics, touristification highlights cultural and spatial changes driven by tourism as well. Moreover, Gil [

24] further underscores the role of short-term rentals as a form of housing assetization that intensifies both gentrification and touristification, contributing to housing shortages and resident displacement. In this context, touristification can accelerate gentrification by enhancing neighborhood appeal for affluent visitors and investors, thereby driving up property values.

Also questioned is the tourism platform economy in relation to sustainability, due to declines in certain consumption patterns and a broader distribution of tourist pressure at the city-wide scale. This may in some cases be relieving pressure on the most congested areas, although critical analyses have countered that the platform tourism model is instead expanding the overall tourism bubble [

8] in certain cities and transferring some of its worst effects (such as pressure on housing) to areas that had previously been spared [

26].

One aspect supposedly facilitated by the platform economy is the likelihood of ‘authentic’ encounters between tourists and locals, contributing to greater integration into the host society and thus improving the tourist experience [

13]. In this narrative, tourists benefit from the added authenticity and uniqueness of staying in a place where they can feel part of a local community, and here providers emphasize the importance of cultural exchanges with guests [

8]. However, we find that, from the consumer perspective, this tourism model is chiefly defended through utilitarian values (cost, location, amenities, features of the accommodations)—the very attributes associated with a traditional hotel. References to the supposed ‘socialization value’ derived from interactions with hosts are rarely encountered in the discourses of guests, seemingly calling into question the claims of platforms like Airbnb that emphasize their role in promoting lasting social relationships [

8].

Dredge and Gyimóthy [

9] conclude that these discourses on authenticity merely seek to romanticize supposedly unmediated encounters between locals and tourists, downplaying the reality of economic exchange. This romanticization further extends to the work that supports such relationships, now conceptualized as a kind of selfless sharing supported by discourses that favor normative transformations toward deregulation and the casualization of labor [

5].

This idealized image would not be possible without the deliberate use of language by platform actors and service providers in their internal narratives. On Airbnb, for instance, words like ‘tourist’, ‘consumer’, and ‘client’ are avoided in favor of ‘traveler’, ‘guest’, and ‘host’. This personalized terminology supports a postmodern, even anti-tourism discourse that emphasizes authenticity and meaningful experiences, while concealing the underlying commercial nature of the exchange [

27]. Providers adopt similar discursive strategies, often describing their offerings not just in terms of functionality—location, amenities, safety—but with language that conveys warmth, cultural identity, authenticity, and the appeal of novelty in everyday settings [

28].

Taking all these factors into consideration, this textual account is structured as follows. First, we discuss the methodology developed, follow by the presentation of the results divided into two parts: a first one that basically reflects the quantitative results, where the discursive competition for the ‘frame’ is revealed; and a second with a fundamentally qualitative approach, where the different discursive rationalities are analyzed. Finally, there is a discussion section where the main conclusions reached are also highlighted.

2. Materials and Methods

As an analytical method, this research uses tools from both corpus linguistics and Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA). While the primary analytical objective of linguistics is discourse itself, from the perspective of social sciences this can serve as a method of approximating social reality or, as in our case, certain aspects of urban socio-spatial reality.

The combination of quantitative and qualitative linguistic methods, known as Corpus-Assisted Discourse Studies (CADSs) by authors like Baker [

29], typically does not begin with strong initial hypotheses. Instead, following Glasser and Strauss’ [

30] Grounded Theory model, it adopts theoretical sampling, where hypothesis formation, data collection, and conclusions are not distinct stages. After an initial analysis, indicators for new concepts emerge, prompting further empirical analysis and the development of new concepts or categories [

31]. Thus, this research thus brings together two seemingly opposing linguistic approaches: corpus linguistics, which is primarily empirical, quantitative, and relatively formalized; and CDA, which uses qualitative methods to explore the links between ideology, power, and/or hegemony, prioritizing critique of the status quo over how people speak [

29]. The theoretical foundations and analytical approaches of both methods are discussed in detail below, in relation to our data analysis procedures.

The main advantage of this crossover lies in corpus linguistics’ ability to detect lexical patterns and language trends across large text collections, often selected through clear, reproducible criteria. This enables researchers to analyze extensive corpora without preconceived notions, addressing common criticisms of discourse analysis—such as relying on small, biased samples chosen to confirm pre-existing beliefs. Accordingly, we work with a sample not constructed to support our own conscious or unconscious biases [

29]. Furthermore, since this methodology is applied within the social sciences rather than linguistics itself, the value of analyzing large volumes of text becomes evident: social impact rarely stems from a single document, but from the cumulative effect of repeated discourses that shape causality, agency, and the roles of speakers and audiences [

32]. In sum, this approach balances quantitative rigor with qualitative, contextual interpretation [

33], as demonstrated by numerous studies linking linguistic findings to broader social, ideological, and intellectual contexts [

34], as well as to geographical and urban settings [

25,

26,

35].

In any case, while no initial hypotheses are offered, and questions may be somewhat imprecise—going beyond what might be answered with a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’ [

29]—one essential starting point is common to all CDA: to “shed light on the problems that people face as a result of particular forms of social life” [

32] (p. 185). Under a social and critical orientation, and here in relation to the platform economy and tourism, this would indicate that situations and processes are addressed in which relations of power and inequality are present. This implies “focusing on a social problem that has a semiotic aspect” [

32] (p. 184) in which said semiosis—“understood as an irreducible part of material social processes” [

32] (p. 180)—contributes to the construction of the socioeconomic reality of a city.

The research questions around which this work has been developed can be described as follows:

How has the connection between the platform economy and touristic activities been discursively represented from distinct ideological positions in shaping a social perception of the new model of the tourism platform economy within a large city, and what power relations and discursive competition do these representations articulate?

‘Touristification’ in Madrid provides the core content from which our main corpus was built. The selection of this term as a central concept was debated, as it could imply a negative view of tourism, leading some media outlets—especially economic or conservative ones—to use it sparingly, thus potentially underrepresenting them in the corpus. Nevertheless, we chose it for two reasons: theoretically, because the negative connotation has been challenged in previous studies [

36,

37], and others have made similar choices [

38,

39]; and practically, because broader terms like

tourism would have produced an unmanageable number of texts, many irrelevant to our aims, making final selection nearly impossible.

The corpus was compiled through extensive searches across twelve newspapers with varied profiles, including some that originated in print and now operate in both print and digital formats, as well as others that are fully digital. The selected titles were

ABC,

Cinco Días,

El Confidencial,

El Diario,

El Mundo,

El País,

El Salto,

Expansión,

InfoLibre,

La Marea,

Libre Mercado,

and Público. Newspapers were chosen due to their influential role—not only in producing discourse but, increasingly, in shaping and reshaping readers’ discourses—despite sharing space with other mass media. These outlets have a notable cumulative impact and, depending on their nature and ideological stance, may convey both hegemonic and counter-hegemonic or resistant discourses [

33].

The text search was carried out online using the keywords ‘touristification’ and ‘Madrid’. We anticipated some selection bias due to the varying quality of search engines across sources—some allowed combined searches (‘touristification + Madrid’), while others required separate queries and manual cross-checking. Searches were conducted between December 2023 and May 2024, with no restriction on article publication dates. As a result, some headings may cover slightly longer periods, depending on when each outlet began publishing or first addressing the topic.

Given the reliance on internet-based searches and the inconsistent quality of newspaper search engines, it was expected that many relevant texts might go undetected. To address this and ensure broader coverage of urban processes, the search was expanded to include articles mentioning ‘gentrification’ + Madrid alongside references to tourism, leisure, or related topics. This strategy aimed to enrich the corpus with texts not captured by the primary search terms but still highly relevant to the article’s focus, as well as to future studies using the same dataset.

Once the documents were downloaded and reviewed, those relevant to our research focus were selected and saved in PDF format. To facilitate reading and, above all, to remove metadata—such as advertisements or reader comments, which could distort quantitative results—each file was then cleaned and saved in plain text using Notepad, retaining only headlines, initial summaries, and the main body of the article.

These documents were used to build the main corpus, which was then subdivided along two lines: temporal and ideological. Chronologically, four five-year periods were defined—2006–2010, 2011–2015, 2016–2020, and 2021–2024. Although no specific starting year was imposed, the term ‘touristification’ appeared rarely before these dates. In fact, the 2006–2010 period was ultimately excluded from the diachronic analysis, as its limited number of occurrences risked distorting the results through disproportionate representation.

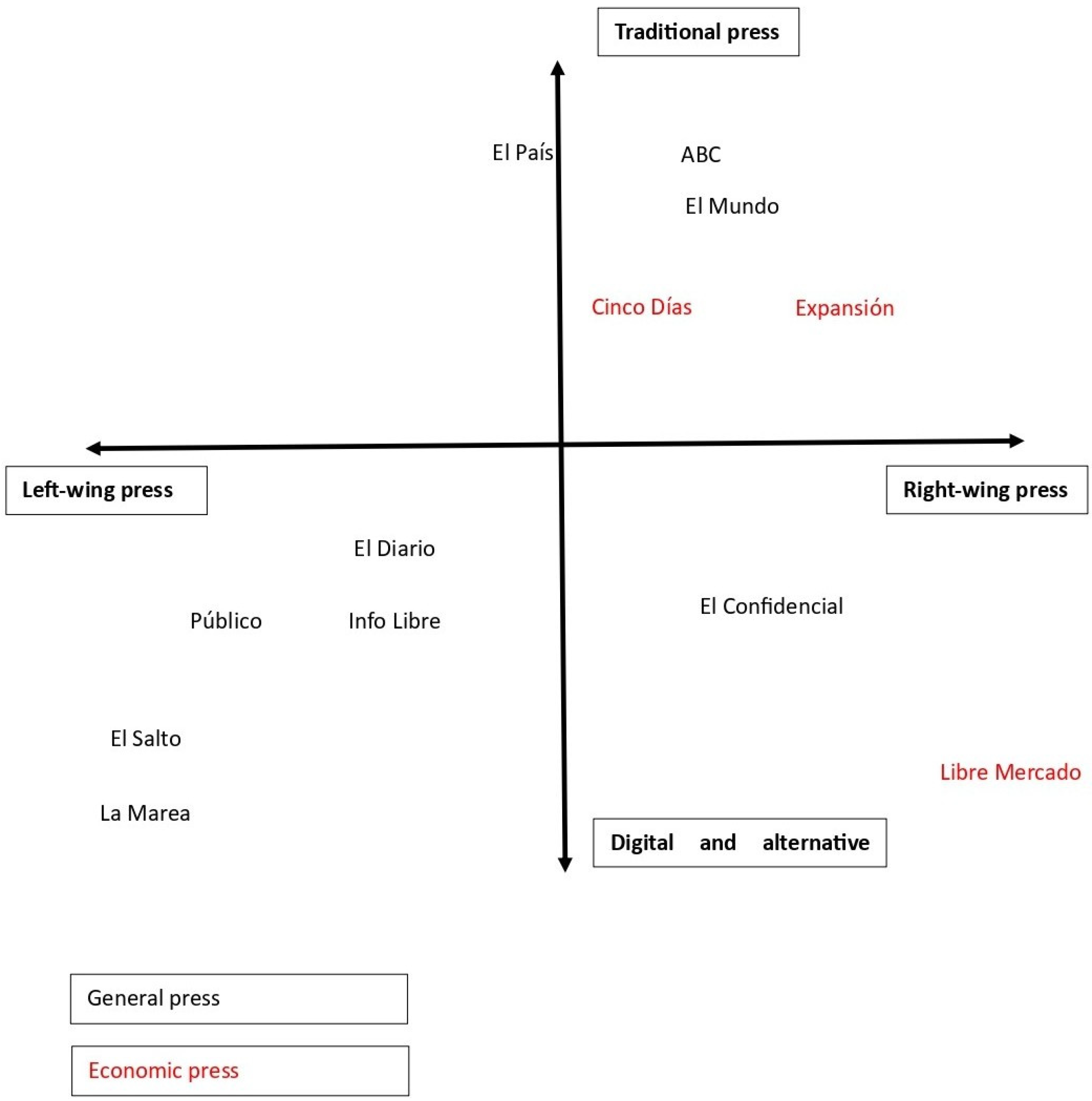

The second method of subdividing the corpus followed ideological lines (‘right’ and ‘left’), as well as media specialization: general versus economic press; mode of distribution (traditional print with online versions versus exclusively digital outlets); and the degree of ideological radicalism (understood without any pejorative intent). This led to the creation of several subcorpora: first, a division between left and right; then, four categories—traditional generalist, traditional economic, left-wing alternative, and neoliberal alternative. These classifications, shown in

Figure 1, were based on the researchers’ assessments and supplemented by various sources detailing each outlet’s ideological stance (subject to critical review).

Dividing the main corpus into several subcorpora—whose sizes are shown in

Table 1—enabled targeted analyses and allowed for both chronological and ideological comparisons. As Baker notes [

33], this approach is appropriate when researchers, drawing on prior knowledge, consider such comparisons potentially valuable from a quantitative or qualitative standpoint. In our study, the quantitative analysis yielded notable results across most subdivisions. However, the qualitative dimension proved less productive: chronological analyses revealed no meaningful discursive shifts over time, and distinctions based on radicalism or publication format were rarely evident. Consequently, ideological interpretations rely primarily on the left–right axis.

The quantitative analyses were carried out using #LancsBox X [

40], a freely accessible concordancer developed by scholars at Lancaster University. The analysis was conducted in Spanish, based on Spanish-language texts. Later, both the analytical concepts and the illustrative excerpts were translated into English. However, the titles of the newspaper articles cited as examples remain in their original Spanish. Full references for all corpus texts, including authorship and access links, are provided in the data availability statement at the end of this paper.

After exploring various options through an inductive approach, two types of quantitative analysis were ultimately selected, as they proved the most fruitful. First, drawing on specialized literature, a list was compiled of keywords commonly used in academic discourse to define and describe the platform economy [

5,

6,

8,

9,

13,

15,

27,

28,

38,

41,

42]. The absolute and relative frequencies of these keywords (per 10,000 words) were then calculated across both the general corpus and the subcorpora. This allowed us to identify the prominence of these academically established terms within the corpus and to qualitatively explore their geographical and ideological implications—whether through their presence, absence, or relative weight. For analytical clarity, the keywords were organized into three Discourse Categories (DCs), based on their narrative significance—understood not only as linguistic expressions, but also as silences and material practices shaped through repetition and reinforced by enactment [

5]. These resulting groupings, or DCs, are as follows:

DC 1. Platform economy, grouping all those terms and their variations (including inflections of gender, number, time, noun or adjective forms, etc.) used to designate, describe, or explain the functioning of the platform economy: platform, technology, digital, collaborative, sharing, etc.

DC 2. Actors, grouping all those terms and their variations that designate people, groups, or companies that serve as agents or patients in the platform economy discourse, and who may be for or against it: Airbnb, Uber, Homeway, investment funds, Platform for People Affected by Mortgages, neighbor, tenant, etc.

DC 3. Changes in socioeconomic relations, grouping all those terms and descriptive variants of the changes (in the opinion of the producers of the discourses) that the platform economy is causing in social relations (host, guest), or as related to housing and the city (housing, rent, eviction).

The second quantitative analysis focused on identifying the most prominent words within each subcorpus. The objective was to pinpoint terms that show a clear statistical divergence between two corpora that potentially represent opposing discursive positions—what Baker refers to as ‘lockwords’ [

29]. In essence, we aimed to detect concepts statistically overrepresented in one corpus relative to a reference corpus, highlighting how certain ideological perspectives emphasize particular themes or ideas in constructing their narratives. Given our interest in geographical, social, and ideological dynamics rather than linguistic patterns, only content words—nouns, adjectives, and verbs—were included, excluding functional elements like prepositions, conjunctions, and articles. The analysis relied on the Log Likelihood statistic provided by the software. This method has been repeatedly applied by the research group that developed it to uncover contrasting ideological stances on both social and extra-linguistic matters—such as the portrayal of Muslim immigration in the UK press, depending on the ideological leanings of the newspapers involved [

43].

The second phase of our methodology involved a qualitative analysis grounded in the principles of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA). Central to this approach is the examination of ‘lockwords’—terms that are statistically more prominent in one subcorpus than in another. This required a close analysis of these key concepts, along with a critical reading of the texts where they appear, to understand how they shape and define a particular discourse in contrast to its counterparts. In our study, the most revealing axis of differentiation was between left-wing and right-wing discourses; accordingly, this distinction became the primary focus of our qualitative analysis.

In this way, we sought to analyze the discursive ‘frame’—in the terminology of Lakoff [

44]—understood as the mental structures that shape the way humans perceive the world and understand language. Frames organize information and activate values and emotions that influence one’s way of thinking and acting. According to Lakoff [

44], language activates these frames unconsciously, so that whoever controls them in public discourse (and even more, whoever has the ability to impose discursive frames on their opponents) has the power to influence perceptions and opinions.

Finally, it should be noted that—distinct from the natural sciences, which are interested in causal explanations—this method seeks to elucidate the apprehension and production of meaning [

31]. In any case, these discourses must be seen as relatively ideal theoretical constructions developed from specific empirical material that are more social than individual in character [

45].

4. Discussion: Housing, Platforms and Tourism in the New Class Division of Urban Societies

As previously noted, this research adopts the premises of CDA, starting from the inequalities and power imbalances existing in society [

52]. Therefore, our primary focus has been the (critically assessed) transformations that urban ‘touristification’ is generally causing [

23,

24,

25,

53], and more specifically the introduction and consolidation of the platform economic model within the urban tourism sector [

5,

9,

11,

16,

18]. This among other aspects has led to a progressive concentration of property ownership along with accelerated financialization of various urban sectors [

24,

54,

55], especially the real estate stock [

16,

24], some of which has been incorporated into the short-term tourist rental market or else commercialized as mass-use urban resources of touristic value. This entails both the worsening of problems around access to housing—already significant in many large cities—and deterioration in the quality of urban life thanks to the incompatibility between mass/unregulated tourism and the ordinary use of the spaces by citizens pursuing ordinary lives [

11,

18].

The differences in perspectives between the left and the right that have been observed (and much more markedly, between the alternative left and right) provokes an interesting discussion around how housing (or rather, the ownership or lack of housing) and its relationship with the (tourism) platform economy is creating a new division within urban societies, sometimes surpassing or overlapping traditional stratifications into social classes [

56,

57]. Indeed, the main conflict within these discourses is not structured around social class—defined in relation to employment and income, to the extent that references to categories like upper, middle, and lower class (or any equivalent) are not detected as predominant—but instead around the separation between those who do not own housing (and are therefore compelled to rent) and individuals who possess ownership of one or more residential properties (and are thus potential recipients of rental income).

This fits with an interpretation that the logic of inequality has been reconfigured since the 2008 financial crisis, which in Spain and Madrid was chiefly regarded as a crisis linked to markets and real estate. In this proposal, inequality is no longer defined by employment status (or by education, or any similar logic referring to income earned through work) but instead by the ability to participate in the asset economy—that is, through the possession of assets that appreciate more quickly than wages and inflation, and through the ability to use such assets (for their profitability, or as collateral for debt) in order to acquire more assets [

56].

This asset-based economy, as discursively presented from a neoliberal perspective, and clearly within our corpus, would not solely be a project of the elites, at least in theory. Indeed, participation would be ostensibly possible (in fact or in theory) from diverse positions, to the extent that among all owners of real estate assets, distinctions could be made between investors, full and direct owners, and owners with mortgages [

57]. It is this last group in particular that is most clearly reflected in our corpus from the perspective of the right-wing discourses (even though, in the end, they constitute merely a small fraction of the overall supply of tourist apartments in Madrid) by way of the emotional neoliberal discourse in favor of the platform economy, through deceptive proposals that all households can conceivably participate in the financialized asset economy [

56].

More or less consciously, the discourses on the urban tourism platform economy included in our corpus embrace these new categories of social division established by the asset economy. This novel social construction implies differentiated representations that entail the need to make and break traditional groups and their collective actions in order to transform the social reality according to new interests [

51]. In fact, discourses romanticizing the platform model seek to overcome the class divisions inherited from Marxism and social democracy, where the result would be a new division between persons willing to mobilize resources to generate new value (economic, at least) versus those who oppose that process. Furthermore, the notion of ‘idle resources’ [

14] would seem to open an unlimited field of intervention to anyone willing to mobilize any sorts of assets, including common ones, thereby reconfiguring the traditional neoliberal idea of meritocracy. This feeds the narrative that anyone can now become part of the asset economy, whether via debt or through ownership of a widely used asset such as housing [

56], valuable in most urban Western societies and specifically in Madrid. The intended conclusion is that to oppose the tourism platform model would be to deny ourselves the possibility of someday joining those who already obtain income from property, which in a virtuous cycle (via profits and debt financed with prior assets) would permit the future acquisition of additional assets.

As indicted by Fairclough [

32], the new model of neoliberal capitalism demands a reconfiguration of the network of social practices, and in this case a specific restructuring of relations between economic and non-economic fields, amounting to a clear colonization of the latter by the former [

32,

58]. What these ideas strive to highlight is that much of the discursive construction favoring the platform economy goes far beyond trying to defend a particular model of tourist production. In fact, neoliberal ideology constructs discourses on the city and urban development that not only defend, legitimize, and justify specific policies, but also render any alternative unthinkable [

59]. In reality, it seeks to construct an entirely new cultural order that, through these and other discursive spheres, restructures social and urban practices around ideas related to autonomy or individuality. In the discourse of capitalism, this will serve to abolish any strategies related to social solidarity and collective responsibility [

60]. As Cockayne [

4] suggests, a new affective geography of neoliberalism can emerge through the interrelation of social and discursive practices.

5. Conclusions

The research question aimed to explore whether competing ideological perspectives engaged in discursive contestation over how the platform tourism economy model was narratively represented. The results obtained by analysis allow us to present two drastically different discourses on the representation through media reporting of the tourism platform economy. The first, which can be described as hegemonic, insofar as it embraces the principles of free market and deregulation that are already clearly predominant within most common economic narratives, here favoring tourism in general and the platform economy in particular. The second, described in terms of resistance, opposes the neoliberal economic system and, accordingly, the socio-spatial model derived from ‘platformization’ of the urban tourism economy. The so-called hegemonic discourse assumes two differentiated ramifications in terms of narrative strategies, coinciding with the two modalities identified by Bourdieu [

51] as dominant discourses once a discursive unanimity based on supposed social consensus has failed: the classic or impartial narrative, and the heretical narrative. In any case, it should be noted that although a clear division between two opposing discursive positions is evident—and it can be argued that narratives surrounding the platform tourism economy are more polarized than those related to urban tourism in general—intermediate positions can also be identified, ranging from full legitimization to critical narratives, as has been observed in other Spanish cities, such as Barcelona [

61].

As might be expected, these two narrative lines of resistance and hegemony frame and ground their rationalities in the social and economic orders, respectively, and they employ different discursive strategies to achieve their ends. Thus, the narrative of resistance often takes up strategies of collectivization (

neighbor is the keyword here, in all its grammatical variations and inflections) in order to broaden the scope of those affected to wider social spectra, ranging beyond any traditional class divisions. The hegemonic narrative often employs a strategy of functionalization, using proper names and especially professional positions of economic prestige (i.e.,

CEO) and arguing from a position of power and authority, to lend gravity and deductive weight to its assertions or ideas [

62].

However, as we have shown, both cases present a discursive line that can be described as emotional and that seeks to empathetically connect the recipient with someone suffering an unjust situation. But while the left and right align on the narrative line (emotion), what clearly differs are the concepts employed and the semantic scope they open up. From the left, this strategy pointedly addresses the person of the tenant, understood as an urban dweller (a neighbor, identified as part of potentially affected group) who does not own the home they live in, which makes them vulnerable to certain negative material processes within the semantic fields of expulsion or eviction. In contrast, in the narrative of the right, the strategy points to groups that define themselves expressly through home ownership (owner, buyer), going so far as to obtain benefits based on their property’s exchange value (landlord). In this case, concepts are used indicating that these owners are people (or families) whose primary interest in the property is its value for use, the exchange value being secondary and/or accidental, or even obligatory; no mention is made of business conglomerates interested in investment, or in the function of housing as a means for capital accumulation.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge the main limitations of this research, which—within the framework of an urban studies agenda focused on processes of touristification and the platform economy—may also be interpreted as productive directions for future investigation. A first step would involve broadening the scope of case studies along two approximately parallel yet interconnected trajectories: on the one hand, expanding the comparative range of urban contexts in order to assess whether the empirically observed discursive competition also emerges in other city models; and on the other, extending the analysis to additional sectors of the platform economy, particularly those related to urban mobility and last-mile delivery services. Moreover, it would be valuable to incorporate alternative forms of discourse, or rather, diverse channels through which such discourses circulate—such as social media platforms or political rhetoric—thus moving beyond traditional media representations.

By integrating these lines of inquiry, it becomes possible to construct a more comprehensive understanding of the discursive logics—and their embedded power relations—that both sustain and contest platform urbanism, ultimately shaping its perception and legitimacy in a broad arrange of different urban imaginaries and, consequently, in the social life of the inhabitants of those cities.