Understanding Paradigm Shifts and Asynchrony in Environmental Governance: A Mixed-Methods-Study of China’s Sustainable Development Transition

Abstract

1. Introduction

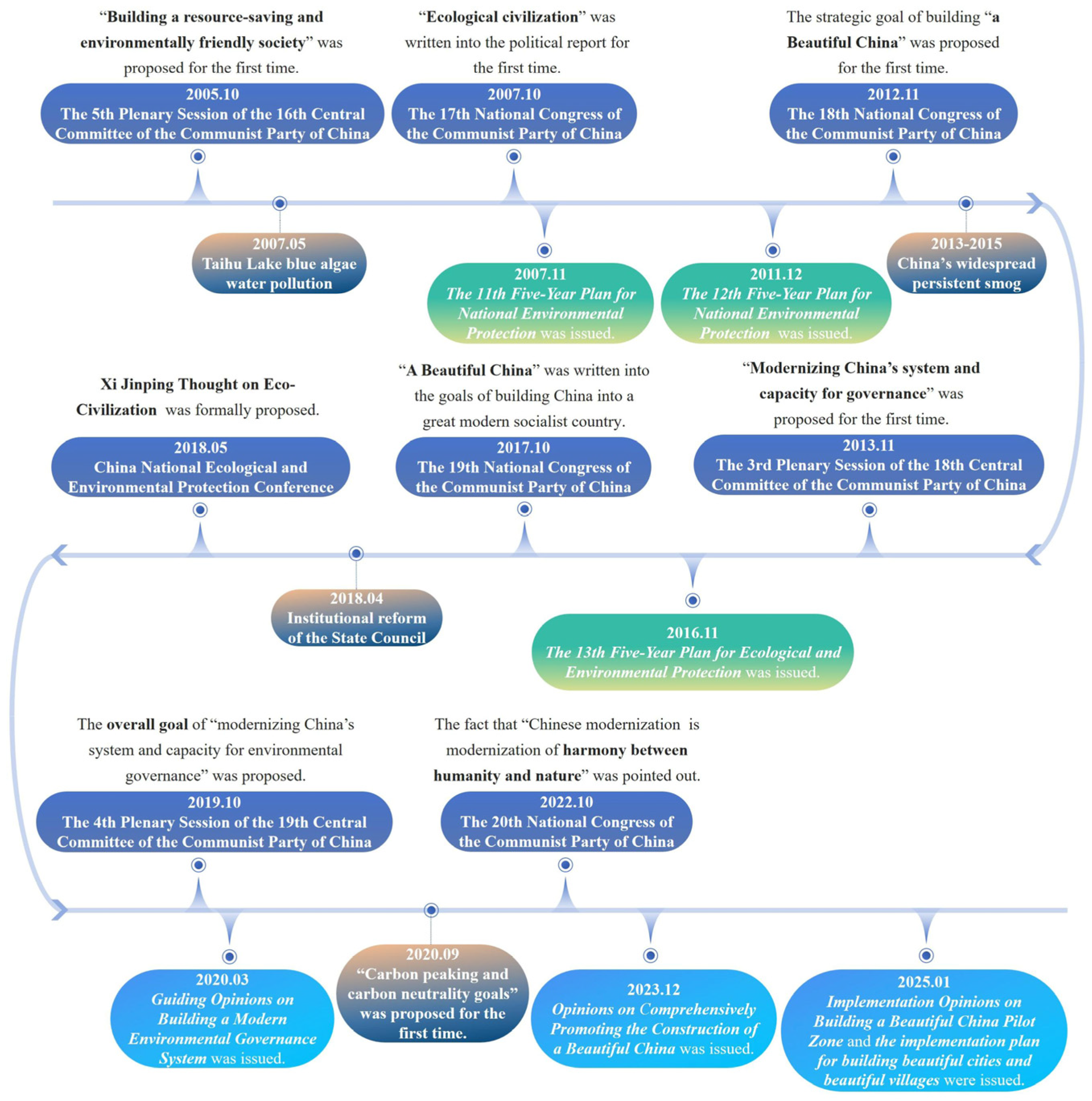

1.1. Background

1.2. Literature Review

1.3. Research Content and Contributions

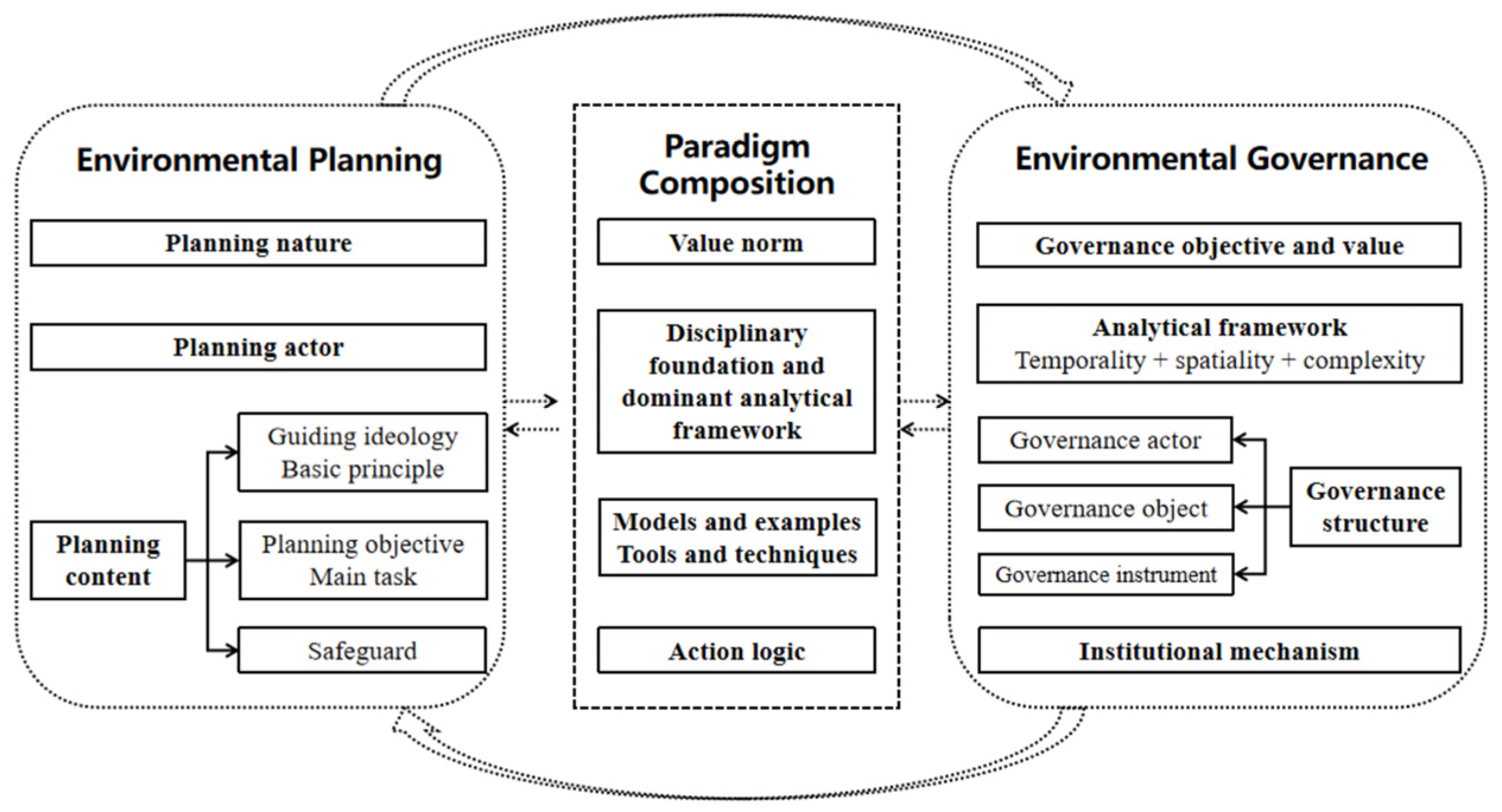

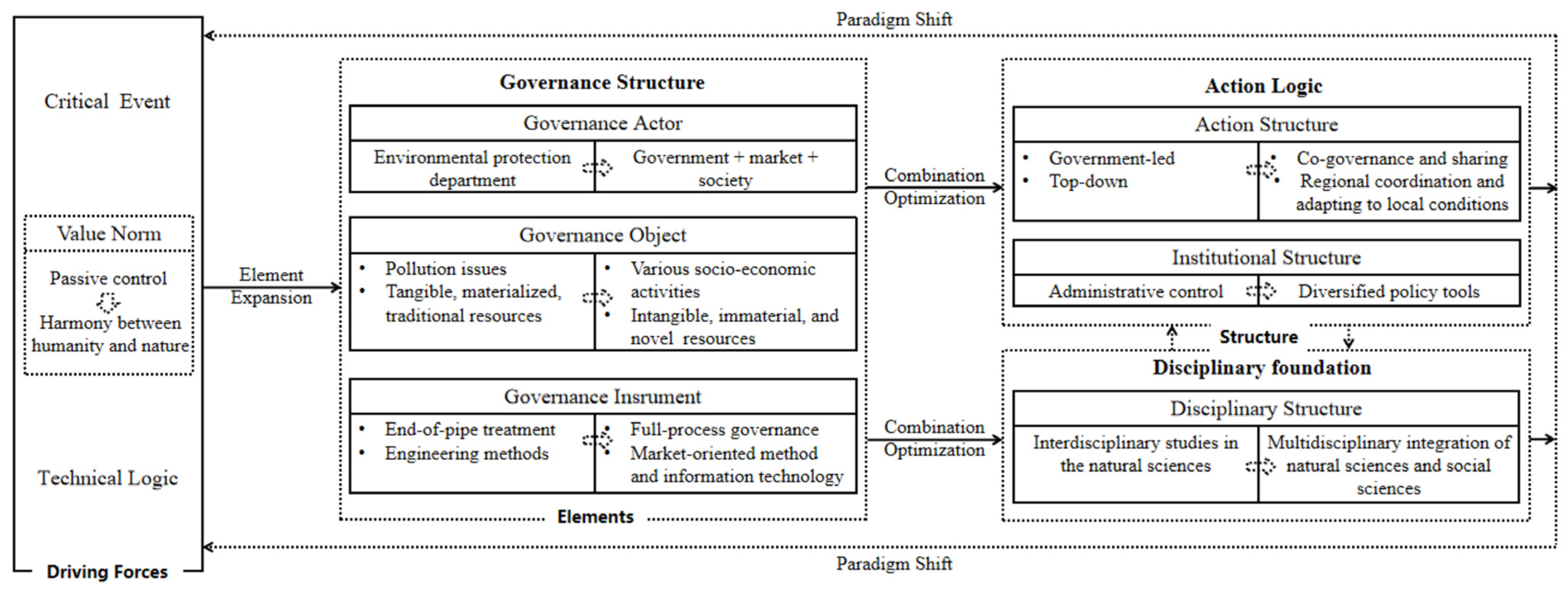

2. Theoretical Framework: Environmental Governance Paradigms

2.1. Defining Governance Paradigms and Shifts

2.2. Comparing Key Paradigms

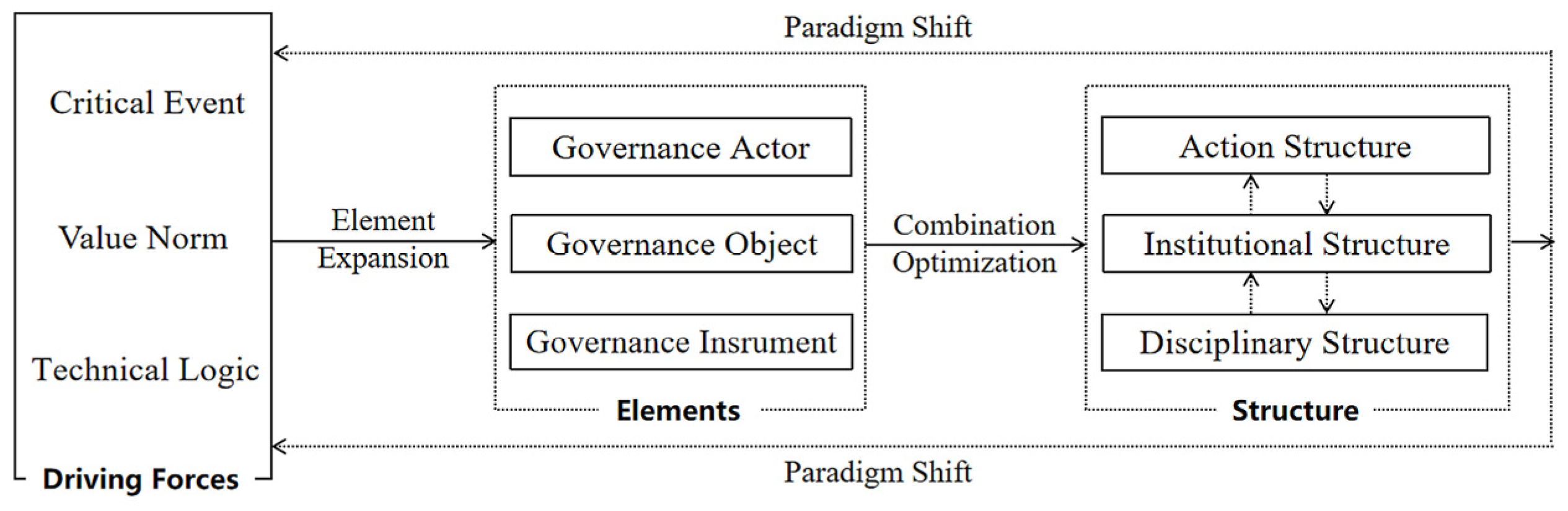

2.3. Analytical Framework: Driving Forces–Elements–Structure

3. Research Design: Data and Methods

3.1. Data: Environmental Planning Documents

3.2. Research Samples

3.3. Methods of Analysis

3.3.1. Qualitative Content Analysis and Critical Discourse Analysis

3.3.2. Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) Topic Modeling

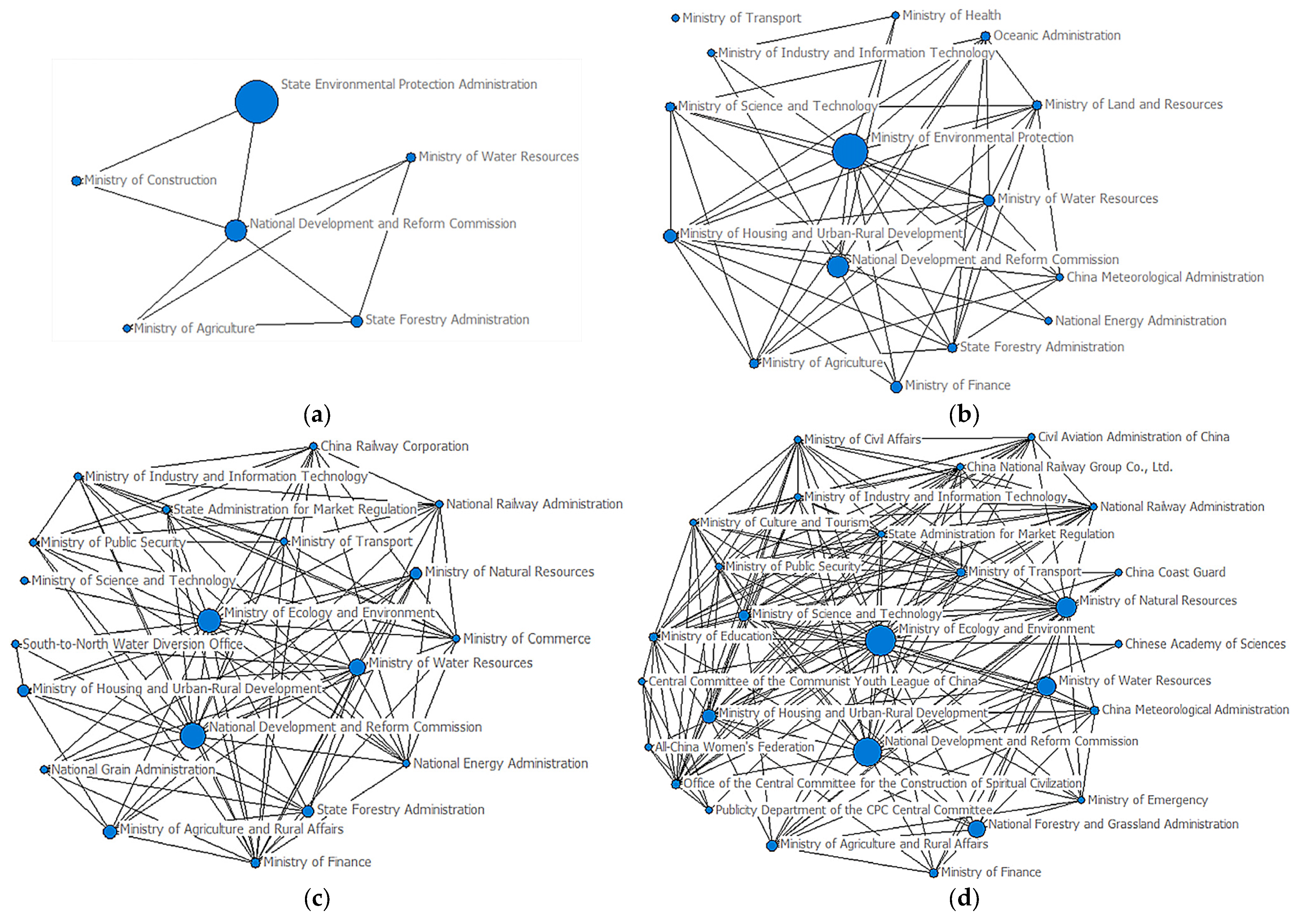

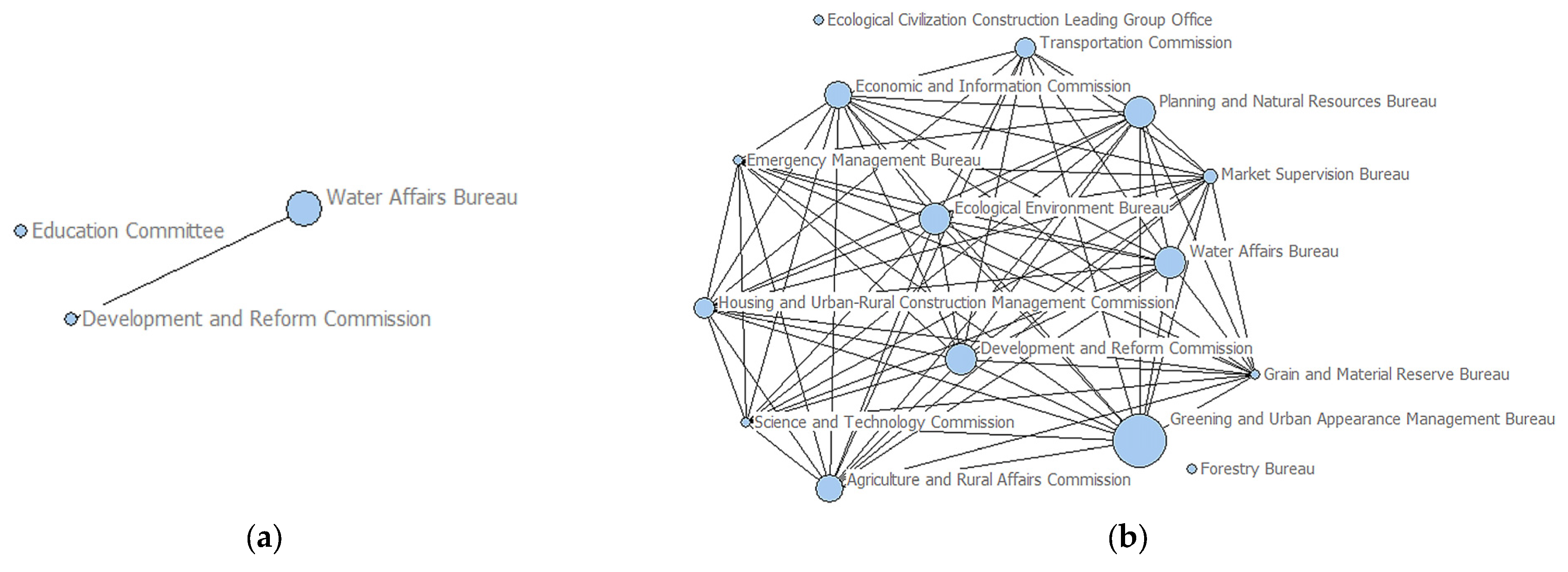

3.3.3. Social Network Analysis (SNA)

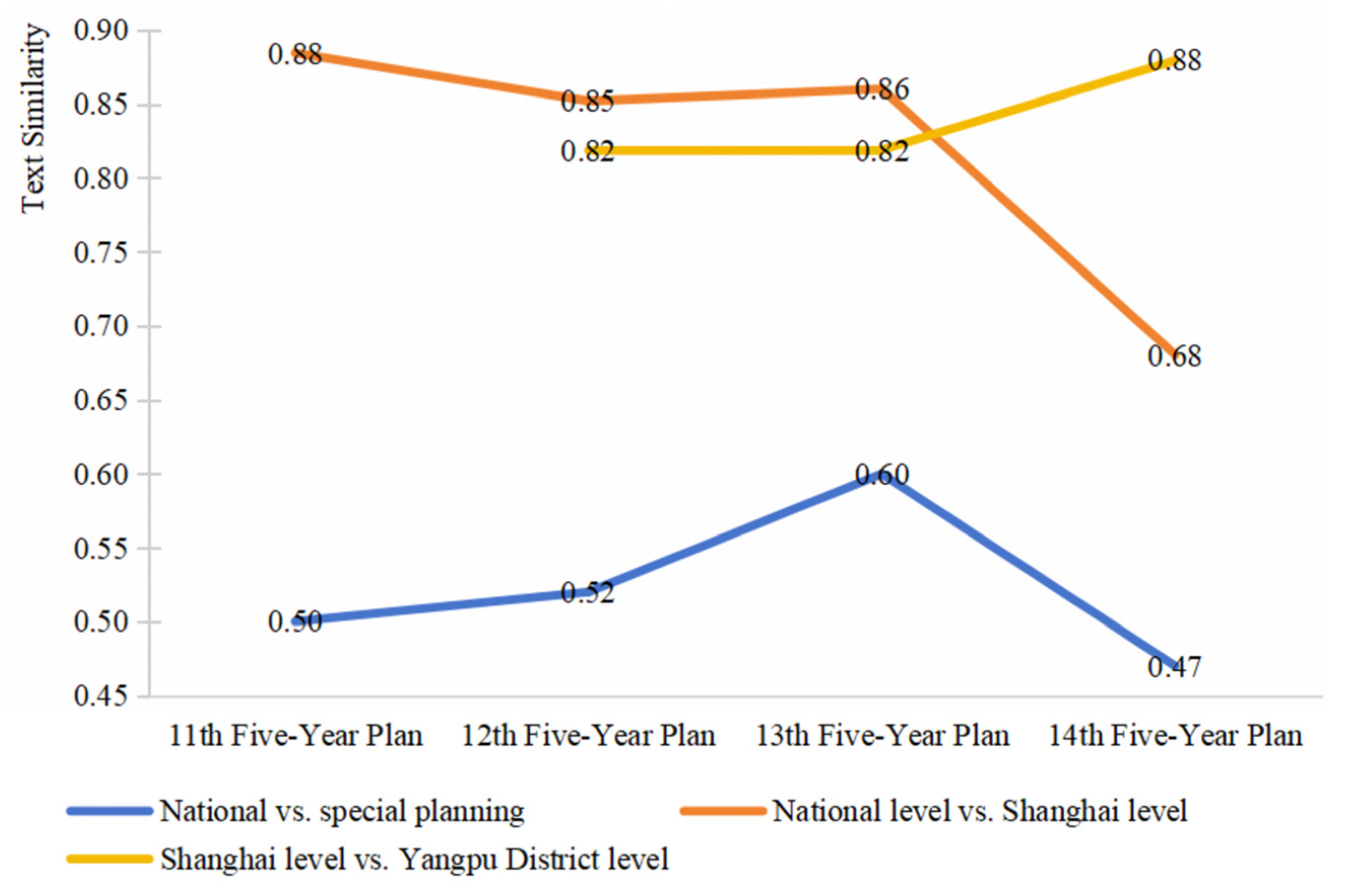

3.3.4. Machine Learning Text Similarity Analysis

4. Findings: Analyzing the Paradigm Shift Through Planning Documents

4.1. Coordination of Multi-Objective Conflicts

4.2. Adaptation of Governance Structure

4.3. Asynchrony of Transformation

5. Discussion and Suggestions

5.1. Results

5.2. Existing Problems

5.3. Policy Recommendations

5.4. Limitations and Prospects

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Environmental planning documents serve as a valuable analytical lens, offering unique insights into the trajectory and nature of national environmental governance paradigm shifts.

- (2)

- The transition from “pollution control” to “ecological conservation” demonstrates pronounced asynchrony: changes in value norms lead, followed by transformations in governance structures, while action logic and the underlying disciplinary foundation exhibit considerable lag. The pursuit of “beauty” (ecological conservation) is driving the reconstruction of the knowledge system, but this concept remains incompletely theorized within the governance framework.

- (3)

- Notable challenges endure at the local level, including an absence of explicit criteria for balancing higher-level mandates with local planning autonomy, and institutional ambiguity in planning authority allocation, both of which impede efficient resource distribution and implementation effectiveness.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| CDA | Critical Discourse Analysis |

| LDA | Latent Dirichlet Allocation |

| SNA | Social Network Analysis |

| TF-IDF | Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency |

References

- Wang, W. Research on the Analysis Framework, Evaluation and Improvement Path of Local Environmental Governance Capacity: A Case of 41 Cities in the Yangtze River Delta. Doctoral Dissertation, Fudan University, Shanghai, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Boulton, C.A.; Lenton, T.M.; Boers, N. Pronounced loss of Amazon rainforest resilience since the early 2000s. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.C.R.; Majid, M.A. Renewable energy for sustainable development in India: Current status, future prospects, challenges, employment, and investment opportunities. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2020, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xiong, C.; Huang, Y. How the River Chief System Achieved River Pollution Control: Analysis Based on AGIL Paradigm. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Geng, X.; Wang, R. Tool Preference and Path Optimization of Environmental Governance Policies——Based on the Content Analysis of 43 Policy Texts. J. Northeast. Univ. Soc. Sci. 2017, 19, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denfanapapol, S.; Setthasuravich, P.; Rattanakul, S.; Pukdeewut, A.; Kato, H. The Digital Divide, Wealth, and Inequality: An Examination of Socio-Economic Determinants of Collaborative Environmental Governance in Thailand through Provincial-Level Panel Data Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Tong, L.; Liu, D. An Empirical Study of the Measurement of Spatial-Temporal Patterns and Obstacles in the Green Development of Northeast China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Xu, Y.; Destech Publicat, I. The Evolution of Environmental Information Attention by Chinese Government: Content Analysis Based on Laws and Regulations and Policy Texts. In Proceedings of the International Conference on E-commerce and Contemporary Economic Development (ECED), Hangzhou, China, 21–22 April 2018; pp. 336–340. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, K.; Zhang, Z. Environmental regulation, green investment and corporate green governance: Evidence from China’s New Environmental Protection Law. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 76, 106979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sok, S.; Lebel, L.; Bastakoti, R.C.; Thau, S.; Samath, S. Role of Villagers in Building Community Resilience Through Disaster Risk Management: A Case Study of a Flood-Prone Village on the Banks of the Mekong River in Cambodia. In Proceedings of the Conference on Environmental Change, Agricultural Sustainability, and Economic Development, Can Tho, Vietnam, 25–27 March 2011; pp. 241–255. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, N.; Bao, C.; Ma, W. Consistency between Environmental Performance and Public Satisfaction and Their Planning Intervention Strategies: A Policy Text Analysis of Urban Environmental Planning. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Feng, L.; Sun, X. Beyond central-local relations: The introduction of a new perspective on China’s environmental governance model. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froehlich, F.M. Food Consumption, Eco-civilization and Environmental Authoritarianism in China. China Q. 2024, 261, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Bird, Y. The Paradox of Responsive Authoritarianism: How Civic Activism Spurs Environmental Penalties in China. Organ. Sci. 2018, 29, 948–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, D.; Heffron, R. Just transition: Integrating climate, energy and environmental justice. Energy Policy 2018, 119, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.E. The Environment and the People in American Cities, 1600s-1900s: Disorder, Inequality, and Social Change; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, S.; Doyon, A. Justice in energy transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2019, 31, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avoyan, E. Collaborative Governance for Innovative Environmental Solutions: Qualitative Comparative Analysis of Cases from Around the World. Environ. Manag. 2023, 71, 670–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, J.; Li, G.; Ai, Q.; Shang, H.; Li, X. Performance Evaluation of Governance Mechanisms of Hazardous Waste Recycling in Rural China: A Qualitative Comparative Analysis Based on Multiple Cases. Eval. Rev. 2025, 49, 420–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulibarri, N.; Imperial, M.T.; Siddiki, S.; Henderson, H. Drivers and Dynamics of Collaborative Governance in Environmental Management. Environ. Manag. 2023, 71, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elinor, O. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Dinda, S. Environmental Kuznets Curve hypothesis: A survey. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 49, 431–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghoff, H. Shades of Green: A Business-History Perspective on Eco-Capitalism. In Proceedings of the Conference on Green Capitalism?: Exploring the Crossroads of Environmental and Business History, Hagley Museum & Library Soda House, Wilmington, DE, USA, 30–31 October 2014; pp. 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, M. Imagination and critique in environmental politics. Environ. Politics 2021, 30, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbah, M.F.; Ezegwu, C. The Decolonisation of Climate Change and Environmental Education in Africa. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rob, N. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, K.; Tang, Y. Governing the Country through Planning: A National Governance Paradigm with Chinese Characteristic. Academics 2023, 4, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, R.G.; Barbosa, R., Jr. Environmental governance under Bolsonaro: Dismantling institutions, curtailing participation, delegitimising opposition. Z. Vgl. Polit. 2021, 15, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, G.; Mawdsley, E. Postcolonial environmental justice: Government and governance in India. Geoforum 2006, 37, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.K. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Z. Chinese Marxist Theoretical Innovation Paradigm Transition of According Mechanisms and Significance. J. Hubei Univ. Econ. 2016, 14, 102–108. [Google Scholar]

- Vanner, R.; Bicket, M. The Role of Paradigm Analysis in the Development of Policies for a Resource Efficient Economy. Sustainability 2016, 8, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J. Implementation of the EU carbon border adjustment mechanism and China’s policy and legal responses. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 110, 107683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gareau, B.J.; Huang, X.; Gareau, T.P.; DiDonato, S. Silent Spring at 60: Assessing Environmentalism in the Cranberry Treadmill of Production in Massachusetts. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 95, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peri, G.; Cirrincione, L.; Mazzeo, D.; Matera, N.; Scaccianoce, G. Building resilience to a warming world: A contribution toward a definition of “Integrated Climate Resilience” specific for buildings—Literature review and proposals. Energy Build. 2024, 315, 114319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Lou, W. Deconstruction and Reconstruction of China’s Ecological Environment Management Paradigm. Jiang-Huai Trib. 2021, 5, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Lu, Y.; Peng, L.; Wang, J. Information, incentives, and environmental governance: Evidence from China’s ambient air quality standards. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2024, 128, 103066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhu, J.; Liu, C. Environmental, social, and governance performance, financing constraints, and corporate investment efficiency: Empirical evidence from China. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Yu, Y.; Yang, S.; Lv, Y.; Sarker, M.N.I. Urban Resilience for Urban Sustainability: Concepts, Dimensions, and Perspectives. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xu, Q.; Xia, G.; Dong, X.; Bao, C. Constructing a paradigm of environmental impact assessment under the new era of ecological civilization in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 99, 107021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Bao, C. A preliminary exploration on the paradigm and application of China’s policy strategic environmental assessment: Based on “value norm-disciplinary substrate and evaluation model-institutional arrangement”. J. Environ. Eng. Technol. 2022, 12, 1817–1824. [Google Scholar]

- Gowdy, J.; Ohara, S. Weak sustainability and viable technologies. Ecol. Econ. 1997, 22, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S. Science studies and language suppression—A critique of Bruno Latour’s we have never been modern. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. 1997, 28, 339–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T. Study and Critic on the Environmental Governance Paradigm of “Event-Emergency”. J. East China Univ. Sci. Technol. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2011, 26, 1–8+19. [Google Scholar]

- Neumayer, E. Weak Versus Strong Sustainability: Exploring the Limits of Two Opposing Paradigms; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R.; dArge, R.; deGroot, R.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M.; Hannon, B.; Limburg, K.; Naeem, S.; Oneill, R.V.; Paruelo, J.; et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 1997, 387, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, T.C. Whither scenic beauty? Visual landscape quality assessment in the 21st century. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2001, 54, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.; Ma, Z.; Liu, B.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, B. Current Status and Outlook for the Development of Environmental Planning Discipline in China. Chin. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 13, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Tian, X. A theoretical exploration on the co—Production of science and social order. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2020, 38, 193–199+207. [Google Scholar]

- Stavins, R. Experience with Market-Based Environmental Policy Instruments. In Handbook of Environmental Economics; Harvard Kennedy School: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. On Conceptual Model for China’s Environmental Governance: A New Paradigm Tool. Environ. Prot. 2020, 48, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Song, C.; Zheng, H.; Polasky, S.; Xiao, Y.; Bateman, I.J.; Liu, J.; Ruckelshaus, M.; Shi, F.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Using gross ecosystem product (GEP) to value nature in decision making. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 14593–14601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassauer, J.I. Cultural Sustainability: Aligning Aesthetics and Ecology; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1997; pp. 65–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Rooij, B. Implementation of Chinese environmental law: Regular enforcement and political campaigns. Dev. Change 2006, 37, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Du, K.; Ouyang, X.; Liu, L. Does more stringent environmental regulation induce firms’ innovation? Evidence from the 11th Five-year plan in China. Energy Econ. 2022, 112, 106110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. The Course of Modernization of China’s Environmental Governance and Its Economic Logic. Southeast Acad. Res. 2024, 6, 113–127+246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Xu, L. Environmental Public Interest Litigation in China: A Critical Examination. Transnatl. Environ. Law 2021, 10, 441–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X. MANDATE VERSUS CHAMPIONSHIP Vertical government intervention and diffusion of innovation in public services in authoritarian China. Public Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 117–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T. Environmental Impact Assessment Procedure for Use During Construction of Building Involves Selecting Evaluation Point for Every Item from Displayed Evaluation Criteria. JP2000020588-A, 21 January 2000. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/JP2000020588A/en?oq=JP2000020588-A (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Maffi, L. Linguistic, cultural, and biological diversity. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2005, 34, 599–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deberdt, R.; DiCarlo, J.; Park, H. Standardizing “green” extractivism: Chinese & Western environmental, social, and governance instruments in the critical mineral sector. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2024, 19, 101516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, S. Blockchain Revolution: How the Technology Behind Bitcoin Is Changing Money, Business, and the World. N. Y. Rev. Books 2018, 65, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Sunesson, K.; Allwood, C.M.; Heldal, I.; Paulin, D.; Roupe, M.; Johansson, M.; Westerdahl, R. Virtual Reality supporting environmental planning processes:: A case study of the city library in gothenburg. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Knowledge-Based Intelligent Information and Engineering Systems, Zagreb, Croatia, 3–5 September 2008; pp. 481–490. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Y.; Qiang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Lu, W.; Xiao, Y.; Chu, C.; Xiong, S.; Shao, C. Environmental sustainability and Beautiful China: A study of indicator identification and provincial evaluation. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 105, 107452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, Z.; Yunlong, P. The Development of New Quality Productivity from the Perspective of Digital Transformation—Theoretical Interpretation based on the “Dynamics-element-structure” Framework. E-Gov 2024, 4, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Redin, J.; Gordon, I.J.; Polhill, J.G.; Dawson, T.P.; Hill, R. Navigating Sustainability: Revealing Hidden Forces in Social-Ecological Systems. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunkuan, B. The Mission and Responsibility of Environmental Planning in the New Era of Ecological Civilization. China Environmental News, 4 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jinnan, W.; Changbo, Q.; Jun, W.; Shangao, X.; Jieqiong, S. Progress and Prospect of the National Eco-Environmental Planning in China. Chin. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 13, 21–28+20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, P.; Gabrielatos, C.; Khosravinik, M.; Krzyzanowski, M.; McEnery, T.; Wodak, R. A useful methodological synergy? Combining critical discourse analysis and corpus linguistics to examine discourses of refugees and asylum seekers in the UK press. Discourse Soc. 2008, 19, 273–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ah, L.H.; Kwon, S. Analysis of Research Trends on Healthy Families Using LDA Topic Modeling: Focusing on the Periods of the 1st to 4th Basic Plans for Healthy Families. J. Fam. Resour. Manag. Policy Rev. 2024, 28, 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Porreca, A.; Maturo, F.; Ventre, V. Fuzzy centrality measures in social network analysis: Theory and application in a university department collaboration network. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 2025, 176, 109319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Li, X.; He, J.; Liu, H. Analysis and application research on spatiotemporal characteristics of microblog information for rainstorm flood disasters emergency rescue based on text classification. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 117, 105085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L. Analysis of the Difficulties and Solutions of “Multi-regulation Integration” under the New Normal. China Collect. Econ. 2016, 7, 39–41. Available online: http://222.198.130.40:81/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=668537145 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Foggin, J.M.; Brombal, D.; Razmkhah, A. Thinking Like a Mountain: Exploring the Potential of Relational Approaches for Transformative Nature Conservation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrend, L.; Levin-Keitel, M. Planning as scientific discipline? Digging deep toward the bottom line of the debate. Plan. Theory 2020, 19, 306–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, I.; Kydd, J. The development and direction of agricultural development economics: Requiem or resurrection? J. Agric. Econ. 1997, 48, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ma, T.; Mi, C.; Shi, R.; Wu, W.; Xia, W.; Zhang, A.; Hu, Q. Current situation and trend of rural environmental planning research domestically and internationally: Visualized bibliometric analysis using CiteSpace. J. Agric. Resour. Environ. 2023, 40, 1012–1027. [Google Scholar]

- Brodkin, E. AGENDAS, ALTERNATIVES, AND PUBLIC-POLICY—KINGDON, JW. Political Sci. Q. 1985, 100, 165–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.A.W. The new governance: Governing without government. Political Stud. 1996, 44, 652–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C.; Thomas, R.P. The Rise of the Western World: A New Economic History; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973; pp. viii+171. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Q.; Cheng, S. Conflict or coordination? The cross-departmental interaction in local environmental governance of China. Environ. Res. 2024, 260, 119657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertha, A. “Fragmented Authoritarianism 2.0”: Political Pluralization in the Chinese Policy Process. China Q. 2009, 200, 995–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Paradigm Composition | “Pollution Control” Paradigm | “Ecological Conservation” Paradigm |

|---|---|---|

| Value norm | Passive control | Harmony between humanity and nature |

| Disciplinary foundation | Interdisciplinary studies in natural sciences | Multidisciplinary integration of natural science and social science |

| Governance structure | Bureaucratic monopoly | Dynamic game of multiple subjects |

| Action logic | Administrative enforcement | Value co-creation integrated with market mechanisms, cultural identity |

| Period | National Level | Shanghai Municipal Level | Yangpu District Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11th Five-Year Plan period | 35 | 3 | 4 |

| 12th Five-Year Plan period | 29 | 9 | 2 |

| 13th Five-Year Plan period | 25 | 6 | 3 |

| 14th Five-Year Plan period | 32 | 24 | 4 |

| Period | Optimal Number of Topics | Topic Name |

|---|---|---|

| 11th Five-Year Plan period | 6 | Solid waste and air pollution control; river basin water pollution control; rural environmental improvement; ecological function protection area; biological species resource protection; environmental technology management system |

| 12th Five-Year Plan period | 9 | Safe treatment and disposal of solid waste; comprehensive control of air pollutants; prevention and control of groundwater pollution; water ecological restoration; river basin water pollution prevention and control; reduction in major pollutants; ecological protection and supervision; development of environmental protection industry; environmental management technology system |

| 13th Five-Year Plan period | 8 | Solid waste pollution prevention and control; river basin water pollution prevention and control; comprehensive water environment governance; ecological space control; ecological economic belt development; regional green coordinated development; supply-side structural reform; green scientific and technological innovation |

| 14th Five-Year Plan period | 5 | Comprehensive governance of river basin water environment; regional joint prevention and control; integrated protection and systematic governance of mountain, water, forest, farmland, grassland, and desert ecosystems; reform in ecological conservation; green technology innovation system |

| Period | Number of Network Relationships | Network Density | Clustering Coefficient | Percentage of Co-Issued Documents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11th Five-Year Plan period | 18 | 0.43 | 1.19 | 28.57% |

| 12th Five-Year Plan period | 98 | 0.41 | 1.49 | 41.38% |

| 13th Five-Year Plan period | 174 | 0.46 | 1.16 | 52.00% |

| 14th Five-Year Plan period | 362 | 0.48 | 1.25 | 62.50% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qu, L.; Shi, J.; Yu, Z.; Bao, C. Understanding Paradigm Shifts and Asynchrony in Environmental Governance: A Mixed-Methods-Study of China’s Sustainable Development Transition. World 2025, 6, 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030090

Qu L, Shi J, Yu Z, Bao C. Understanding Paradigm Shifts and Asynchrony in Environmental Governance: A Mixed-Methods-Study of China’s Sustainable Development Transition. World. 2025; 6(3):90. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030090

Chicago/Turabian StyleQu, Lin, Jiwei Shi, Zhijian Yu, and Cunkuan Bao. 2025. "Understanding Paradigm Shifts and Asynchrony in Environmental Governance: A Mixed-Methods-Study of China’s Sustainable Development Transition" World 6, no. 3: 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030090

APA StyleQu, L., Shi, J., Yu, Z., & Bao, C. (2025). Understanding Paradigm Shifts and Asynchrony in Environmental Governance: A Mixed-Methods-Study of China’s Sustainable Development Transition. World, 6(3), 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030090