1. Introduction

As the global trend of population aging intensifies, especially in high-density Asian cities, the concept of “aging in place”, the ability of older adults to continue living safely and comfortably in familiar environments, has become a pressing urban and public health concern [

1,

2]. This issue is particularly salient in Macau, a compact, multicultural city where the aging population is rising rapidly and community-based care systems are still evolving [

3]. In this context, older adults’ emotional attachment to public spaces is emerging as a key factor for their psychological resilience, social participation, and long-term well-being [

4,

5]. A growing body of literature underscores that the success of aging in place is deeply rooted in place attachment—the emotional bond individuals form with specific environments [

6,

7]. For older adults, such bonds transcend private dwellings and increasingly encompass community public spaces where everyday activities and social interactions unfold [

1,

8,

9].

In high-density urban contexts such as Macau, community public spaces—including local parks, small plazas, temple forecourts, and neighborhood rest areas—function as extensions of older adults’ everyday living environments [

10,

11]. Often regarded as communal “living rooms,” these spaces host routine activities such as morning exercises, casual conversations, board games, sunbathing, and neighborhood interactions [

12]. Through sustained, repetitive use, they become repositories of memory and emotion, woven into the fabric of older adults’ lived experiences [

13]. As such, these spaces transcend their physical utility and evolve into emotionally and socially supportive environments [

14,

15]. Recent studies have shown that continued engagement in such spaces significantly strengthens older adults’ sense of community identity and emotional attachment [

5]. Such community spaces fulfill essential psychological needs by offering companionship, routine, and a connection to local culture, thereby supporting aging-in-place through emotional bonds to the environment [

16].

Place attachment, commonly defined as the emotional bond between people and specific physical environments, is a foundational concept in environmental psychology and gerontology [

7,

17,

18]. Existing studies identify a wide range of factors influencing place attachment in later life, including physical environmental qualities, social opportunities, and psychological needs [

19,

20,

21]. However, these factors are rarely examined in an integrated manner. Meanwhile, increasing evidence suggests that such influences are not exerted independently, but rather through complex mediating pathways, such as environmental satisfaction, social participation, or place meaning [

22,

23,

24]. Despite this, empirical research remains limited, particularly in relation to aging in place within the context of public spaces in high-density Asian cities. Moreover, the relationship between place attachment and aging in place remains insufficiently understood. Existing traditional place attachment theories have yet to effectively capture the long-term residential intentions and emotional bonds of older adults within the specific context of later-life stages, leaving a significant gap in current research.

To address these research gaps, this study introduces and operationalizes a specialized form of attachment, referred to as “aging-in-place attachment (AiPA)”, which reflects the aging experience within community environments and is conceptualized as an emotionally grounded commitment by older adults to age within the public spaces of their community. Consistent with Scannell & Gifford’s Person–Process–Place framework [

6], AiPA leaves the Person and Place poles intact but extends the Process pole by foregrounding three late-life indicators. Building upon place attachment theory and incorporating the physical, psychological, and behavioral specificities of aging, this study argues that AiPA is particularly salient in high-density urban settings such as Macau, where spatial limitations, cultural hybridity, and demographic pressures converge. To empirically examine this concept, the study proposes a comprehensive analytical framework that investigates the formation mechanisms of AiPA among older adults in Macau. It draws a multisource methodology combining spatial, behavioral, psychological, and physiological data. The study investigates four principal dimensions of influence: physical environmental variables [

25,

26], behavioral patterns [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33], human-factor metrics [

34,

35], and psychological factors [

16,

25,

27,

28,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. The outcome variable, aging-in-place attachment, is conceptualized as an extension of place attachment theory and is measured using three indicators: willingness to remain in the current location, satisfaction with the environment, and perceived dependence on the local community.

The central research question guiding this study is as follows: In the context of high-density Asian cities such as Macau, to what extent do physical environmental features, spatial behavior patterns, human-factor data, and psychological variables explain older adults’ attachment to aging in place, and how do these variables contribute, individually and collectively, to the explanatory power of the proposed empirical model? Regarding the analysis method, while Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) has been widely adopted in this field for its capacity to model latent constructs and complex mediation pathways, hierarchical regression analysis offers a complementary approach that allows for a clearer examination of the incremental explanatory power of grouped variables, particularly useful when evaluating nested or context-specific factors in aging-related studies. This stepwise approach not only complements SEM but also better isolates context-sensitive variable clusters in empirical aging studies. By applying hierarchical regression analysis, this study sequentially assesses how these variables explain AiPA, allowing us to test the relative and layered importance of physical, behavioral, physiological, and psychological factors.

Ultimately, this study delivers three interlocking contributions. First, it introduces AiPA—a construct that fuses classic place-attachment theory with the explicit intention to remain in one’s community, thereby translating an abstract psychological bond into a policy-relevant indicator for age-friendly planning. Second, by integrating five data streams—site-scale spatial audits, behavioral observations, eye-tracking + GSR metrics, matched questionnaires, and in-depth interviews—this study assemble a multi-layer evidence base that has been employed in only a handful of related studies, allowing the relative weights of environmental, behavioral, sensory, and psychological drivers to be compared within one unified model. Third, the focus on Macau’s hyper-dense, culturally hybrid public spaces fills a geographical gap in the literature and yields design guidance for other Asian cities where land scarcity and rapid population aging collide. Taken together, these advances offer both a theoretical bridge between environmental psychology and gerontology and an evidence-based toolkit for architects, planners, and policymakers seeking to create emotionally resonant, socially vibrant, and spatially feasible environments for older adults. Future research can extend this framework by testing intergenerational dynamics, digital engagement, or institutional supports to refine AiPA across diverse urban contexts.

3. Materials and Methods

Overview of the mixed-methods design. To guide the reader through the study’s multi-layered methodology, the authors summarize the full sequence here before presenting each module in detail. Five data-collection modules were executed in the order listed: (1) a physical audit of nine community spaces (N = 9 sites); (2) systematic behavioral observation of older-adult users at those sites (N ≈ 7800 observational snapshots); (3) a laboratory-based eye-tracking + galvanic-skin-response experiment with 63 elders drawn from the same neighborhoods; (4) a matched questionnaire survey of those 63 participants covering place attachment, behavioral intention and demographics; and (5) semi-structured interviews with 13 of the surveyed elders to elicit narrative depth. All quantitative streams were integrated through hierarchical regression to assess the incremental explanatory power of each variable block, while the interview material was thematically analyzed to contextualize and challenge the statistical results. The subsequent

Section 3.1,

Section 3.2,

Section 3.3,

Section 3.4,

Section 3.5,

Section 3.6 and

Section 3.7 describe each module in full.

3.1. Study Area

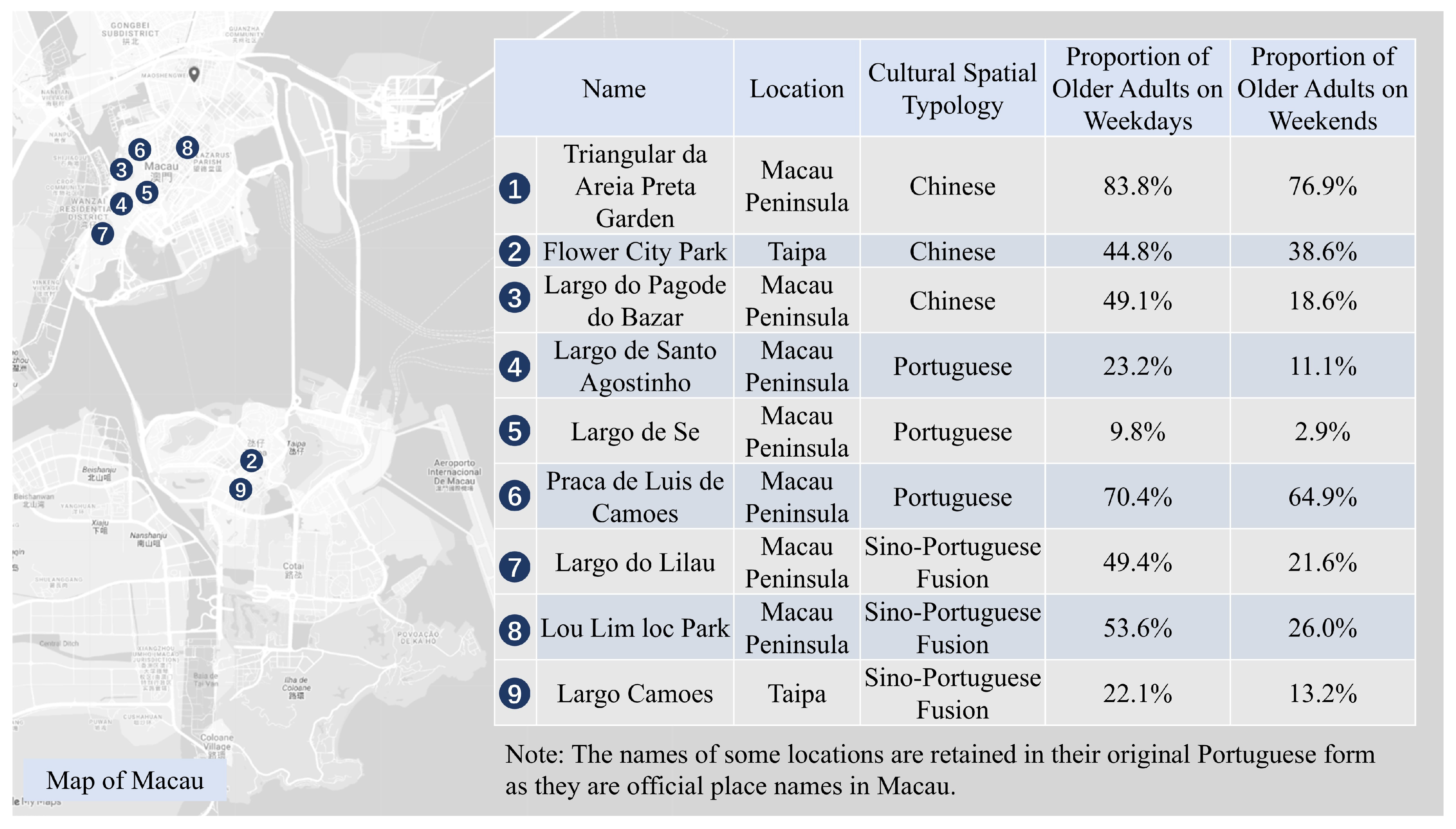

This study identified 9 community public spaces in Macau through a purposive sampling strategy, guided by criteria of representativeness, cultural diversity, and research feasibility. Selection considerations included the spatial scale of the site, the functional variety of facilities, and, most importantly, the frequency of older adult usage. Preference was given to locations situated within neighborhoods with a high density of older adults, as these spaces are deeply embedded in daily routines and social practices. To reflect Macau’s unique socio-cultural landscape, place meaning, social configuration, environmental atmosphere, and levels of local integration, the selected sites were categorized into three typologies: (1) traditional Chinese-style spaces, (2) Portuguese-influenced spaces, and (3) hybrid Sino-Portuguese spaces. Although the spatial sizes varied, all nine spaces share characteristics of medium-scale open areas typical of Macau’s urban plazas, which have historically supported community interaction and daily living.

Figure 1 illustrates the spatial distribution and cultural classification of the selected sites, mapping their location across various urban districts. It also includes comparative data on the proportion of older adult users observed during weekday and weekend periods, providing an empirical foundation for assessing patterns of use and engagement. Data was collected through systematic field observations conducted specifically for this study. A preliminary version of these observational data and site classifications was previously published in the context of instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) research [

12]. The current study extends this earlier work by applying the data within a new conceptual and analytical framework focused on AiPA.

3.2. Physical Features of Community Public Spaces

The assessment of Macau’s public spaces was grounded in the conceptual framework of aging in place [

58], with particular attention to how the built environment can support autonomy, well-being, and sustained social interaction in later life. Drawing from an interdisciplinary scoping review of place attachment and environmental gerontology [

21], three key dimensions of physical features were identified: spatial characteristics, natural elements, and elder-friendly and accessible design attributes [

12].

For spatial characteristics, metrics included site area, spatial enclosure, paved surface ratio, and visual brightness uniformity. Natural elements were evaluated through metrics such as visible greenery ratio, plant species diversity, and green area proportion. The elder-friendly and accessible design dimension included facility diversity, the density of resting and leisure amenities, and entrance accessibility. All data were collected through systematic field observation, supported by local geospatial sources where applicable.

Table 1 (adapted from [

12]) succinctly lists every metric, the computation formula, data source, and reference. For example, spatial enclosure was derived through a combined GIS-and-field procedure. Building-footprint and parcel data (scale 1:1000) were obtained from the Macau Online Map and imported into ArcGIS Pro 3.1. For each public-space polygon, the Boundary-Facing Length—the cumulative length of built or vegetated edges situated ≤ 3 m from the space boundary—was extracted with the Near analysis tool. These lengths were then verified in situ with a Leica Disto D510 laser range-finder (mean absolute error = 0.07 m). Spatial enclosure was measured by the ratio of the enclosing boundary length to the perimeter of the space, producing the following values: 44.44%, 37.22%, 7.96% for the three Chinese-style squares; 59.10%, 84.01%, 27.80% for the Portuguese-style squares; and 32.32%, 66.44%, 78.36% for the Sino-Portuguese hybrids. The nine-site range (7.96–84.01%) and overall mean (48.6%) confirm a wide spectrum of enclosure conditions across Macau’s community spaces. These SE percentages, together with site area, paved-surface ratio, and visual-brightness uniformity, form the spatial-features block later entered into the hierarchical regression models.

3.3. Behavioral Observation

This study used systematic non-participant observation at all nine sites to document older-adult engagement. The protocol was informed by the SOPARC system (System for Observing Play and Recreation in Communities) developed by McKenzie [

71], and further structured according to Gehl’s [

72] recommendations for multi-day, multi-period behavioral scans in urban settings.

Preliminary counts in two test plazas revealed five elder-activity peaks—early-morning exercise (08:30–10:30), late-morning errands (10:30–12:30), post-lunch respite (14:30–16:30), pre-dinner gathering (16:30–18:30) and evening strolls (19:30–21:30). Each site was therefore scanned in these five periods on eight non-consecutive days (four weekdays, four weekend days) randomly distributed across one month, producing 800 min of observation per site. In every period, the observer selected the first 20 min (e.g., 08:30–08:50) and performed a slow left-to-right sweep; an individual was recorded only when the focal action remained clearly visible for at least 30 s.

Actions were first classified as necessary, optional, or social. Necessary behaviors (e.g., hurried shortcutting) were logged for completeness but, following Gehl, omitted from later statistics because they are weakly design-sensitive. Optional behaviors were subdivided into static (resting, reading, listening to music, viewing scenery) and dynamic (walking, fitness-walking, tai-chi, use of exercise equipment, gardening, dog-walking) sub-types. Social behaviors comprised any interaction involving two or more persons—conversation, child-minding, chess or card games, group opera, community volunteering, family gatherings, and the like. When multiple actions occurred, the behavior occupying the longest share of the scan was logged to avoid double-counting. Two trained coders double-scored 12% of the video-assisted scans (Cohen’s κ = 0.89); one coder then completed the remaining files.

The number of older adults, their proportion relative to total users, and the frequency of each activity type were systematically recorded. Contextual factors, such as weather conditions or special events, were also documented to control environmental influences. Observations conducted under poor weather conditions were excluded and rescheduled.

3.4. Human-Factor Data Collection

To explore how older adults respond visually and emotionally to community public spaces, this study employed an integrated approach using eye-tracking and GSR data for 63 older adults. Visual stimuli consisted of nine high-resolution images depicting typical public spaces in Macau. These images were selected for their cultural representativeness, environmental complexity, and relevance to the daily experiences of adults aged 65 and over. Photos were captured at natural eye-height (1.55 m) under consistent daylight conditions (12–14 klx), ensuring standardization across all scenes. Each image measured 4500 × 2532 dpi (16:9 aspect ratio) and was georeferenced to reflect actual locations. Static images were chosen as visual stimuli due to their high experimental controllability and proven validity in simulating real-world visual experiences. Henderson [

73] showed that static scenes elicit naturalistic gaze patterns, while Berto [

74] confirmed their effectiveness in triggering environmental responses. Compared to interactive 3D models, images reduce older adults’ variability and physical exertion and allow precise control over visual input.

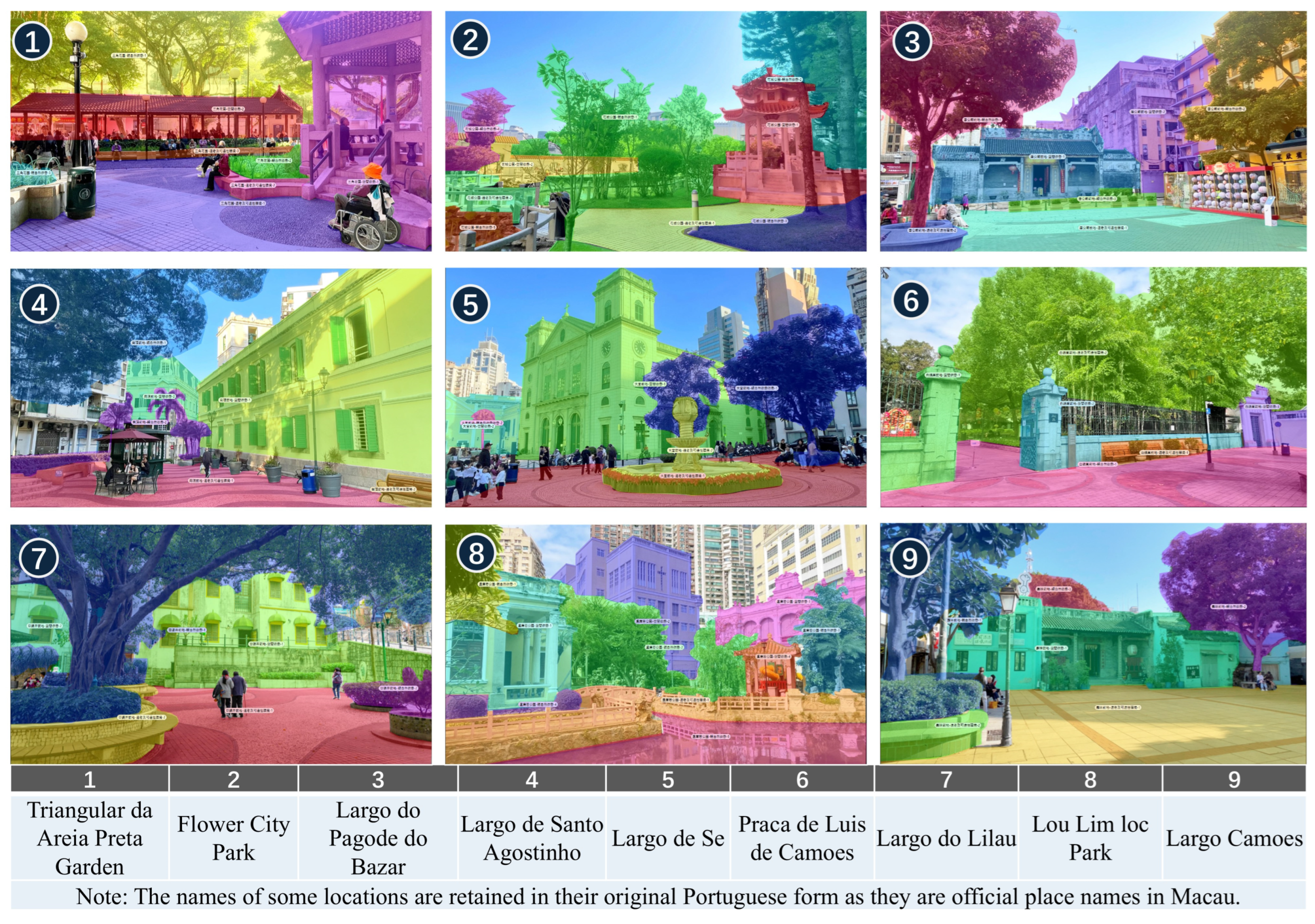

To ensure representativeness and cognitive resonance, the nine stimuli were drawn from three spatial types—open plazas, linear street-courts, and pocket gardens—within each of Macau’s major cultural morphologies: Chinese, Portuguese, and hybrid. Although the selected spaces vary in physical size, their inclusion was guided by the medium-scale characteristics typical of Macau’s largos, which are generally recognized as appropriate for the everyday use and mobility patterns of older adults. Candidate images were first assessed by three architectural experts using a 5-point representativeness scale, and only those reaching a content validity ratio (CVR) of ≥0.78 were retained. This selection was further validated by six local older adults who rated their familiarity with each scene (mean ≥4.0/5). To minimize saliency bias and control visual complexity, we used Vision Complexity v1.4 to compute edge density (target range: 2.4–3.0%) and Shannon entropy (target range: 6.1–6.4 bits); only images falling within these thresholds were included.

Areas of interest (AOIs) were defined within each image to categorize visual attention based on three physical dimensions of place attachment: (1) spatial attachment (e.g., building façades, sculptures), (2) nature attachment (e.g., vegetation, water features), and (3) age-friendly/accessibility features (e.g., seating, pathways, signage). AOIs were defined within each image to categorize visual attention based on three physical dimensions of place attachment: (1) spatial attachment (e.g., building façades, sculptures), (2) nature attachment (e.g., vegetation, water features), and (3) age-friendly/accessibility features (e.g., seating, pathways, signage). AOIs were manually delineated using Tobii Pro Lab software (Version 24.21) and were designed to cover approximately 80–90% of each image frame, ensuring visual balance across the three categories. The remaining 10–20% of each image was left as a buffer zone to preserve natural gaze behavior. Representative thumbnails overlaid with AOI boundaries are presented in

Figure 2.

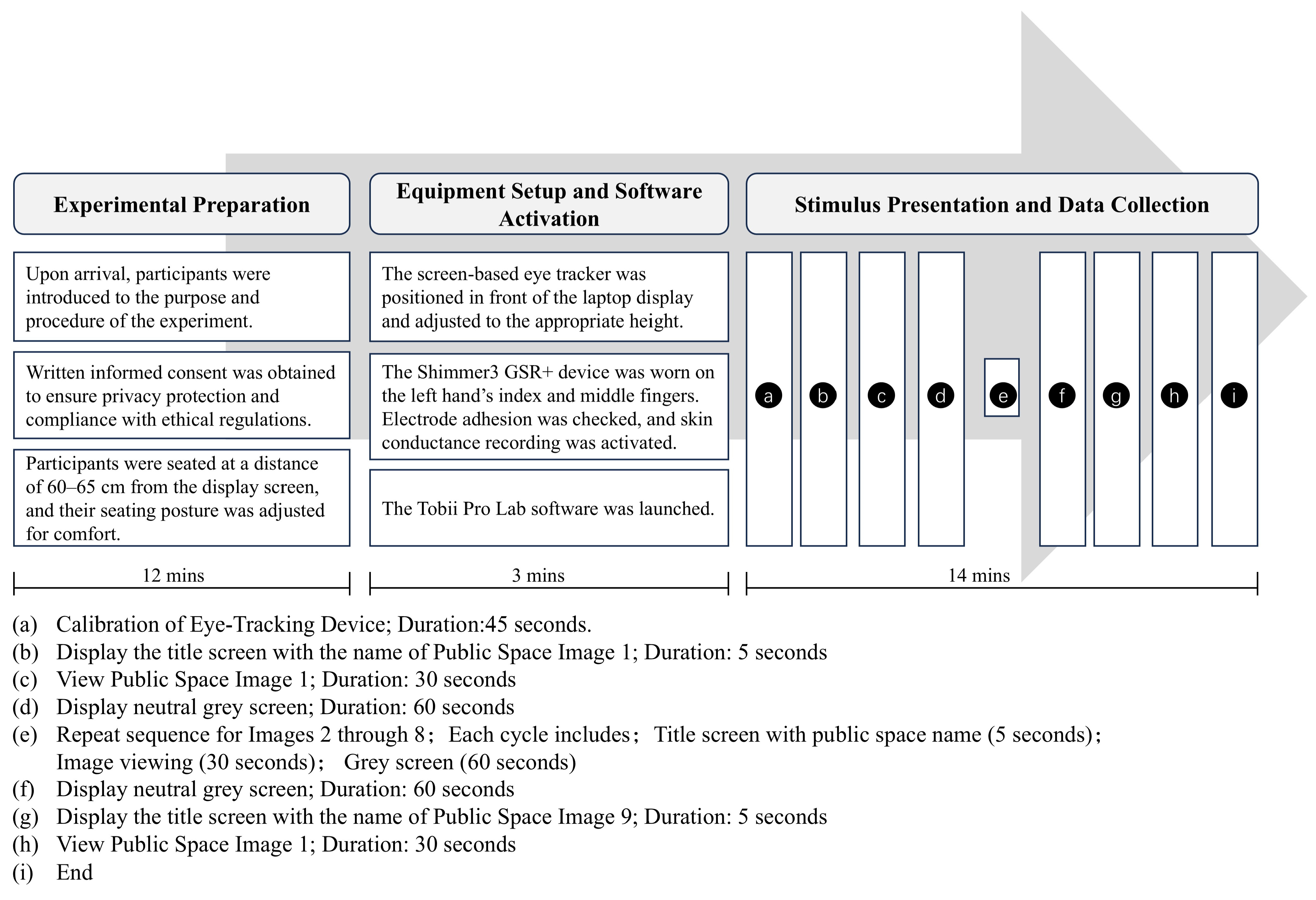

The experiment was conducted using the Tobii Pro Nano eye-tracker (Tobii, Stockholm, Sweden, 60 Hz sampling rate, 0.3° accuracy) and the Shimmer3 GSR+ sensor (Shimmer wearable Sensor Technology, Dublin, Ireland) to record physiological responses. Data collection occurred in familiar elder activity centers to maximize comfort and ecological relevance. Participants were seated 60–65 cm from a 19-inch monitor, with ambient luminance maintained at 400–500 lux (measured using a digital lux-meter) and A-weighted background noise kept below 40 dB to minimize sensory distractions. Prior to data collection, all the participants provided written informed consent and completed a 9-point calibration procedure using Tobii Pro Lab. Calibration was accepted when the root-mean-square gaze error was below 0.4°, and it was repeated whenever significant head movement occurred during the session. Each participant viewed the same sequence of nine visual stimuli, randomized using a Latin square design. Each stimulus block consisted of a 5 s title screen, a 30 s stimulus image, and a 60 s mid-gray wash-out screen to mitigate carry-over effects.

Synchronization between the Tobii Pro Nano and the Shimmer3 GSR+ was achieved through Tobii Pro Lab software, which ensured precise temporal alignment of eye-tracking and skin conductance data without requiring external hardware triggering. Gaze and GSR signals were recorded simultaneously throughout the experiment. A complete experimental session, including calibration and stimulus presentation, lasted approximately 30 min. The procedural workflow is illustrated in

Figure 3. This dual-modality approach provided empirical insight into the multisensory mechanisms of elder place attachment, capturing both attentional engagement and physiological arousal in response to visual features of community public spaces.

3.5. Questionnaire Survey

The questionnaire captured perceptions and intentions to analyze psychological mechanisms of AiPA. Human-factor data collection and questionnaire administration shared the same 63 elders who had just completed the eye-tracking + GSR protocol, thereby ensuring a one-to-one correspondence between physiological and self-report measures. This consistent participant design enhances the complementarity and comparability of the data, allowing for a multidimensional understanding from both psychophysiological and cognitive–affective perspectives.

As for sampling and recruitment, community-center rosters drawn from the ten census tracts with the highest proportion of residents aged ≥65 years were first stratified by population density; within each stratum, sex (~50% women/men) and age-band quotas (65–74, 75–84, ≥85 years) were imposed. Face-to-face contact with 80 elders produced 68 individuals who satisfied the inclusion criteria (≥65 yrs; ≥5 yrs continuous local residency; MoCA-C ≥ 18; normal/-corrected vision). Sixty-three completed both the laboratory session and the questionnaire, giving an effective response rate of 78.8% (63/80). Demographic profile (analytic n = 63). The final sample comprised 33 women and 30 men (mean ± SD age = 72.6 ± 6.1 yrs). Educational attainment was primary or below (61.9%), secondary (31.7%), and tertiary (6.3%); monthly personal income fell into four brackets: <MOP 4000 (15.9%), 4000–9999 (42.9%), 10,000–19,999 (38.1%), and ≥20,000 (3.1%). Median local residency was 28 years, 62% were currently married, and 93.7% self-identified as ethnically Chinese (4.8% Macanese; 1.5% other).

The present questionnaire’s purpose serves as the primary source for evaluating subjective perceptions and behavioral expectations. It also underwent a pilot test and ethical review to ensure appropriateness and robust protection of participants’ personal data. The questionnaire consists of two major modules. The first module focuses on individual background and cognitive–affective responses, including demographic information, patterns of space use, cultural orientation, and perceptions related to aging in place. Notably, this module includes the study’s core dependent variable, Aging-in-Place Attachment, a sub-concept developed to enrich the classical theory of place attachment. The second module assessed place attachment and environmental intention toward nine space scenarios. Together, these tools generate subjective perceptual data that corresponds with the physiological responses captured in the experimental setting. The Place Attachment Scale is based on the Abbreviated Place Attachment Scale (APAS) proposed by Boley [

75], which divides place attachment into two dimensions:

Place identity and place dependence, each measured by three concise items to ensure reliability while maintaining feasibility for older adults. The Environmental Behavioral Intention component is designed with reference to key theories in environmental psychology, such as Kaplan’s restorative theory and Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior, assessing participants’ perceived comfort, relaxation, social engagement, and intention to linger in the given spatial scenarios. All attitudinal statements employed 5-point Likert scales (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The interviewers were formally trained and followed an assisted-completion protocol to minimize literacy barriers; any questionnaire with > 10% missing items was excluded (none within the final 63 cases). The complete English-language instrument has been moved to

Appendix A. The questionnaire functions not merely as a supplementary dataset but as a pivotal and independent tool for capturing sociopsychological variables. Together with the physiological data, it establishes a multidimensional, integrative framework for analysis.

3.6. Semi-Structured Interviews

To illuminate the psychological mechanisms that underpin the quantitative indicators of aging-in-Place Attachment, a program of semi-structured interviews was carried out with 13 elders—approximately 20% of the analytic cohort (n = 63)—recruited through maximum-variation purposive sampling so that sex, age band, educational attainment, and cultural orientation were all represented. Each conversation was conducted in Cantonese in a quiet room of the respondent’s community center immediately after completion of the laboratory and survey sessions and lasted 30–40 min. The interviews were audio-recorded with informed consent, transcribed verbatim, translated into English, and analyzed in NVivo 12 by following Braun and Clarke’s thematic procedure [

76]; inter-coder agreement reached κ = 0.82, and thematic saturation was evident after the twelfth transcript.

The interview guide comprised four thematic modules and thirteen open-ended prompts (

Table 2). This structure ensured the coverage of personal background, spatial–emotional ties, everyday behavioral patterns, and future expectations while still allowing respondents to elaborate freely. Although only about 20% of the questionnaire participants took part in the interviews, and their responses are not broadly representative, their narratives offer valuable subjective insights. These perspectives provide potential explanations for selected quantitative findings and contribute to the theoretical understanding of aging in place.

3.7. Data Analysis

This study employed a multi-stage data analysis strategy to examine the explanatory power of various factors on older adults’ AiPA in the Macau public spaces. Data sources included structured spatial measurements, behavioral observations, questionnaire responses, and physiological data collected through eye-tracking and electrodermal activity (EDA). Prior to analysis, all datasets were cleaned, screened for outliers, and normalized using min–max scaling when appropriate. The questionnaire data underwent reliability and validity checks to ensure the robustness of the instrument.

To address the central research question—namely, how much additional variance each block of variables contributes to AiPA—we conducted hierarchical regression analysis in IBM SPSS Statistics (version 26; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Variables were entered stepwise in four blocks to evaluate their incremental contribution to explaining AiPA. This approach allowed the assessment of how each factor group improved model fit (ΔR2) and explanatory power. Significance was set at p < 0.05.

4. Results

4.1. Questionnaire Reliability and Validity Analysis

To ensure the robustness of key constructs—particularly place attachment and AiPA—the questionnaire underwent comprehensive reliability and validity assessments.

Reliability analysis was conducted using Cronbach’s alpha to evaluate the internal consistency of each multi-item scale. The results indicated that all core constructs exceeded the commonly accepted threshold of 0.70, demonstrating satisfactory reliability. Specifically, the aging-in-place attachment scale (α = 0.754), composed of three items reflecting residential continuity, environmental satisfaction, and community dependence, exhibited acceptable internal coherence. Similarly, high levels of reliability were observed for place identity (α = 0.915), place dependence (α = 0.908), place attachment (α = 0.934), and place behavioral intention (α = 0.921). Item-total correlations confirmed the contributions of individual items to overall scale reliability, with selective deletion analysis reinforcing the decision to retain theoretically meaningful items.

Validity analysis included content and construct validation. Content validity was established using well-established scales adapted to the local context. Construct validity was tested via Principal Component Analysis (PCA) with Varimax rotation. For the aging-in-place attachment scale, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value was 0.677 and Bartlett’s test was significant (p < 0.001), indicating sampling adequacy. A single factor was extracted (eigenvalue = 2.046), accounting for 68.19% of total variance, with all factor loadings exceeding 0.78—supporting a unidimensional structure. Similar procedures confirmed the factorial validity of the other latent constructs.

These results confirm that the questionnaire exhibits strong psychometric properties, thereby ensuring the reliability and construct validity required for subsequent statistical modeling.

4.2. Hierarchical Regression Analysis

Based on the preceding discussion and dataset structure, this method allowed for the stepwise entry of predictor blocks to assess the incremental explanatory power of each category. Specifically, physical environmental attributes were entered as Block 1 in the SPSS regression model, followed by spatial behavioral variables (Block 2), human-factor data (Block 3), and finally, place-related psychological variables (Block 4).

As shown in

Table 3, the progressive inclusion of predictor blocks significantly improved the model’s explanatory power. Model 1, which included only physical environment indicators, yielded an R

2 of 0.054, suggesting that environmental factors alone explained only 5.4% of the variance in AiPA—a limited contribution. When behavioral variables were added in Model 2, R

2 increased markedly to 0.204 (ΔR

2 = 0.150), indicating the substantial explanatory power of behavioral engagement in public spaces. Model 3, which incorporated human-factor data, achieved a modest R

2 improvement to 0.244 (ΔR

2 = 0.040), suggesting that while biometric and behavioral metrics provided added value, their contribution was relatively smaller. Finally, Model 4 introduced place-psychological variables, resulting in a substantial R

2 increase to 0.836 (ΔR

2 = 0.592).

Further examination of standardized coefficients (see

Table 4) in Model 4 reveals nuanced insights. Among physical environment variables, spatial attachment (β = 0.069,

p = 0.003) exhibited a weak but statistically significant positive effect, suggesting that familiarity and a sense of belonging may modestly enhance AiPA. In contrast, natural attachment showed a significant negative effect (β = −0.454,

p < 0.001), implying that those with a stronger affinity toward natural environments may be less inclined to remain in urbanized public spaces. The accessibility and age-friendliness index also showed a small negative association (β = −0.063,

p = 0.031), which may reflect a limited impact of infrastructural improvements on deeper emotional attachment.

With respect to behavioral variables, both static (β = −0.410, p < 0.001) and dynamic behavior indicators (β = −0.269, p < 0.001) were negatively associated with AiPA. This suggests that passive occupation of space or overemphasis on exercise-related activities may not contribute positively to emotional bonding with place, possibly due to reduced opportunities for interaction or the functional, transient nature of such engagements. In contrast, social behaviors (β = 0.814, p < 0.001) had the strongest positive effect, reaffirming the pivotal role of interpersonal interaction in the formation of place attachment in later life.

Human factors produced mixed effects. Total gaze duration within areas of interest (β = 0.096, p < 0.001), single visit duration (β = 0.091, p = 0.001), and frequency of visits (β = 0.084, p = 0.002) all showed significant positive associations with AiPA, indicating that visual attention and habitual presence reinforce emotional attachment. However, total dwell time (β = −0.111, p = 0.003) exhibited a negative effect, suggesting that mere physical presence without meaningful engagement may not foster attachment. Other biometric indicators, such as electrodermal activity and fixation counts, did not reach statistical significance (p > 0.05), pointing to limited direct predictive power in this context.

Most notably, place psychological variables had the strongest predictive effect. Place attachment (β = 0.670, p < 0.001) emerged as the most influential factor in the final model, reinforcing the centrality of emotional bonding in aging-in-place decisions. Behavioral intention toward continued engagement with the place (β = 0.177, p < 0.001) was also a significant predictor, suggesting that intentionality mediates the relationship between place experience and long-term settlement preferences. Together, these findings substantiate the theoretical model proposed in earlier chapters, affirming that AiPA in high-density urban environments is shaped by a layered interplay of physical, behavioral, biometric, and psychological factors, with place-based emotion serving as the most critical determinant.

The ANOVA results (

Table 5), generated using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 26.0, confirm the overall statistical significance of all four regression models (

p < 0.001), with Model 4 achieving the highest F-value, further validating the robustness of the full model. These results underscore the necessity of integrating both objective and subjective dimensions in urban aging research and offer an empirical basis for designing emotionally resonant, socially vibrant, and behaviorally inclusive elder-friendly public spaces.

4.3. Conceptual Definition and Weighted Model of AiPA

To synthesize both the quantitative findings and qualitative insights, this study defines AiPA as a multi-dimensional construct shaped by four key domains—environment (E), behavior (B), human-factor (H), and psychology (P)—corresponding to four regression blocks that together explained 83% of its variance. This study represents AiPA using the following conceptual formula:

where

E = physical environmental features;

B = observed behavioral patterns;

H = human-factor metrics;

P = psychological and emotional variables;

α, β, γ, δ = empirically derived weights from the model;

Q = Qualitative narratives from semi-structured interviews;

ε(Q) = A qualitative interpretive adjustment term reflecting lived experiences and symbolic meaning.

Based on the final hierarchical regression results(ΔR

2): α = 0.054, β = 0.150, γ = 0.040, δ = 0.592; and the cumulative adjusted R

2 = 0.836. Thus, the normalized weighted model becomes as follows:

The normalized weights show psychological factors dominate (≈70.7%), highlighting the central role of emotional bonding in aging-in-place decisions. Behavioral engagement (B) accounts for a substantial secondary role (18%), while physical attributes (E) and human-factor cues (H) serve as foundational yet relatively modest contributors. Here, Q represents insights derived from semi-structured interviews, serving as a qualitative explanatory adjustment term that does not directly affect the statistical weights but enriches the model by revealing lived experiences, cultural meanings, and affective narratives, and supplements internal logic. This mixed-method formulation of AiPA provides a comprehensive framework to assess aging-in-place dynamics. It offers an empirically grounded, transdisciplinary conceptual tool to guide future evaluation and design of age-supportive urban environments. Having established the relative weights of each domain, we next interpret their theoretical and design implications.

5. Discussion

This study addresses three gaps raised in the introduction—(i) the lack of a metric that couples classic place-attachment theory with the explicit intention to age in place, (ii) the scarcity of multisource evidence that weighs environmental, behavioral, sensory and psychological drivers within a single model, and (iii) the near-absence of data from hyper-dense Asian streetscapes. By operationalizing the AiPA construct and analyzing five convergent data streams collected in Macau, we show that late-life attachment is dominated by psychological bonding (≈71% of explained variance), followed by social behavior (18%), human-factor engagement (5%), and the built environment (7%). These findings from Macau’s ultra-dense streets thus offer design guidance for other space-constrained cities seeking to foster successful aging in place.

5.1. Emotional and Social Dimensions as Core Drivers of AiPA

The results confirm that emotional bonds and social behaviors are key drivers of AiPA, aligning with place attachment theory [

6,

21]. In the hierarchical model, the inclusion of place attachment and related psychological variables yielded the largest increase in explanatory power, underscoring that an older person’s sense of belonging and identity with a locale is paramount in the decision to age in place. This aligns with longstanding observations that, in later life, familiar places become intertwined with one’s self-concept and life history [

7]. Likewise, social engagement emerged as a critical ingredient: the frequency of sociable behaviors (e.g., conversing, group activities) had a highly positive association with AiPA (β ≈ 0.81,

p < 0.001). This echoes prior studies, which show that strong neighborhood ties and community participation anchor older adults to their environment and enhance well-being [

7,

54]. In contrast, solitary or purely utilitarian use of space (e.g., sitting alone or exercising without social interaction) did not contribute to attachment; such static or non-social activities were negatively associated with AiPA. This observation reinforces theories that place attachment in later life is co-constructed through shared experiences and interactions rather than through passive habitation of the environment [

54,

77]. From an architectural perspective, these results highlight that the design and programming of public spaces should prioritize opportunities for social interaction and community-building among seniors. Seemingly ordinary community spaces, such as a small plaza, a park corner, or a temple forecourt, can serve as vital emotional refuges and “third places” for older adults. In Macau’s compact neighborhoods, such spaces function as extensions of the home environment, offering accessible venues for daily routines, face-to-face contact, and leisure. Over years of repeated use, these settings become imbued with personal memories and shared meaning. Consistent with the notion of public space as a community asset [

78]. For practitioners in architecture and urban design, this finding underlines the importance of creating age-friendly communal spaces that are not only physically comfortable but also socially vibrant–places where older people can form friendships, sustain rituals, and reinforce their sense of identity and belonging.

5.2. The Facilitating Role of the Physical Environment

While emotional bonds and social life dominate AiPA, the physical environment remains a crucial facilitator in the background. Although environmental features alone explained just 5% of variance, they play an indirect yet enabling role in fostering attachment. A well-designed, familiar, and safe environment provides the stage upon which social and psychological processes play out. As our results suggest, spatial features had a modest positive effect on attachment, implying that legible and elder-friendly design can help older adults feel at ease and “at home.” This corresponds with the idea that environmental familiarity and comfort enable the confidence to engage socially, thereby nurturing attachment over time [

7,

50]. Participants who valued greenery reported lower AiPA, suggesting a mismatch between their preferences and Macau’s dense, built environment. This finding highlights a potential design gap: incorporating more nature or biophilic elements into urban community spaces could help satisfy the preferences of nature-oriented seniors and enhance their emotional connection to otherwise hardscaped settings. Macau’s dense neighborhoods offer limited greenery, so improving even small aspects might significantly improve emotional fulfillment for users who yearn for natural environments. This counterintuitive result may indicate that when basic amenities (ramps, seating, lighting, restrooms) are present and meet a minimum threshold, further enhancements in infrastructure do not automatically translate into stronger place bonds. Older people appreciate such features, but their emotional attachment depends more on what they do in space than on the checklists of physical provisions. However, it is important to note that without a baseline of good design–safety, comfort, and accessibility–many older adults would likely not use the space enough to develop any attachment at all. For instance, if a plaza has unsafe crossings or no seating, seniors may avoid it, forfeiting the chance to socialize and form memories there [

50]. In this way, the physical environment plays a supportive, enabling role: it can encourage or discourage engagement. The findings suggest that in high-density cities, architects and planners should view environmental design as a facilitator of social interaction and psychological comfort. In summary, the built environment alone may not create attachment, but it sets the conditions for attachment to flourish by making spaces welcoming and usable for older people.

5.3. Sensory Engagement and Human-Factor Insights

By integrating human-factor metrics (eye-tracking and GSR data) into the analysis, this study offers a novel perspective on how older adults physically and emotionally engage with public space, an area rarely examined in traditional architecture and gerontology research. Although adding these sensory–cognitive indicators produced a moderate increase in explained variance (about 4%), the results are positive.

Longer gaze duration on salient features, higher visit frequency, and longer per-visit fixation all showed positive associations with AiPA, implying that active visual sampling, not merely being on-site, feeds place bonding. This echoes Kaplan’s restorative-environment theory that “soft fascination” fosters cognitive ties to the setting [

79] and aligns with recent neuro-ergonomic work demonstrating that repeated attentional loops consolidate spatial memory [

80]. The negative link between total dwell time (β = −0.11,

p = 0.003) and AiPA becomes intelligible when read through the environmental press–competence model. Lawton & Nahemow posited that when environmental challenges exceed an older person’s adaptive capacity, prolonged immobility may signal passive coping rather than attachment; subsequent field studies of mobility limitation in later life support that view [

81]. Webber likewise found that elders who “stay put” for long stretches in public plazas often do so because they feel unable—not unwilling—to circulate [

82]. Our data suggests the same: if time on a bench is not punctuated by scanning, conversation, or micro-movement, it contributes little to emotional anchoring.

The physiological arousal measure (GSR) did not show a meaningful relationship with attachment. This aligns with findings that older adults often exhibit attenuated sympathetic arousal in familiar, low-threat settings [

83]. Low GSR in our sample thus likely reflects a comfort–security state rather than disengagement, echoing socio-emotional-selectivity research showing that seniors prioritize calm, meaningful environments over novelty [

84]. This insight cautions researchers that not all physiological signals of engagement are straightforward in the context of place bonding. Taken together, these results suggest a dual mechanism: focused visual attention cements memory traces, while low-arousal safety feelings consolidate attachment.

From a design standpoint, these human-factor findings highlight the importance of creating environments that can capture attention and invite repeated use. Features that draw the eye, such as natural elements, public art, or active street life, and that sustain interest over time, can encourage older visitors to mentally engage with space. Likewise, providing environments that reward exploration (e.g., varied pathways, points of interest, comfortable micro-spaces to pause) may lead to more frequent and longer visits, strengthening attachment. As architects and urban designers consider age-friendly spaces, multi-sensory design becomes crucial. Future research could build on this by combining physiological data with neurocognitive measures and in-depth qualitative interviews, examining how specific design elements evoke emotional responses and meaning for older users. This incorporation of human-factor data reinforces how older adults perceive and interact with the physical setting in real time is an integral piece of the attachment puzzle, one that merits further exploration in both research and practice.

5.4. Multidimensional Pathways and the Life-Course Perspective

AiPA emerges from the interaction of physical, social, and psychological factors rather than from any single domain. Instead, the results support an integrative view long suggested by environmental gerontologists and place theorists [

21,

58]. For example, while the physical environment provides opportunities or barriers, those translate into attachment largely through their influence on behavior and satisfaction. That the model explains over 80% of the variance supports the view that AiPA reflects a lifetime of accumulated place experiences: the built environment they inhabit, the social relationships they maintain there, and their internal reflections and meanings all feed into a holistic sense of place identity. This perspective is consonant with Rowles’ classic observations of place attachment as a layered phenomenon (physical, social, autobiographical) built over time, and with recent calls to examine aging in place through multiple lenses simultaneously [

9]. One implication is that mediating mechanisms likely play a significant role. Prior studies using SEM have indeed found that factors like neighborhood satisfaction or perceived safety mediate the relationship between environmental qualities and well-being in older populations [

23,

54]. This study sees indirect evidence of such pathways: higher social activity levels coincided with greater attachment, and one can infer that an age-friendly environment facilitates those activities by making elders feel safe and comfortable to participate. Similarly, our human-factor data suggest that engagement and attention mediate the environment-attachment link; features that captured gaze and curiosity likely made the environment more enjoyable, fostering attachment beyond the physical amenities themselves. Adopting a life-course perspective, it is also important to recognize how personal history interweaves with these factors. Many of our participants had decades-long familiarity with their neighborhood, meaning that their attachment is also the product of temporal depth. The longer one lives in a place, the more opportunities there have been for the physical setting to serve as a backdrop for memories (children raised, festivals celebrated, hardships endured) and for the social network to solidify. Longer residence deepens attachment not only through behavior [

7,

20], but through the life narratives that build place identity over time. For urban scholars and designers, this multifaceted understanding means that promoting aging-in-place is not just a matter of modifying bricks-and-mortar; it requires supporting the social fabric and acknowledging the personal histories tied to a place. Interventions should be synergistic: physical improvements must go hand in hand with community programs and services that engage older residents, and both should resonate with the cultural and historical context that seniors value. The findings encourage moving beyond siloed approaches to aging-in-place research and practice, instead embracing models that link environment, behavior, and psychology into one continuum of experience.

5.5. Theoretical Contributions and Methodological Insights

By conceptualizing and empirically testing “Aging-in-Place Attachment,” this study contributes to theory in both place attachment research and environmental gerontology, particularly from an architectural vantage point. Classic place attachment theory has long recognized that people form deep bonds with places, but it has not explicitly focused on the intention to age in place as a distinct facet. This study extends the concept by highlighting how, in late life, attachment involves not just loving a place, but being committed to staying put in that place as one grows older. This adds a new dimension to place attachment that is closely tied to autonomy, security, and identity in old age. The results support theoretical arguments that familiar places provide a sense of continuity and control that is critical for “successful aging” [

77]. This emphasis on continuity echoes observations by Wiles [

1] and others that aging in place is valued because it allows elders to maintain a sense of self and normalcy through stable surroundings. Additionally, our findings nuance the concept of rootedness, the long-term embeddedness in a place. While scholars like Lewicka [

7] have noted that length of residence often strengthens attachment, our analysis suggests that such rootedness is not a passive result of time alone. It is actively reinforced by ongoing engagement, the social ties one nurtures, and the personal meanings one continually ascribes to the environment. In other words, time in place contributes to attachment insofar as it is filled with meaningful relationships and experiences. This highlights a theoretical point: place attachment in late life is a dynamic, evolving process, not merely a residual of the past. The study provides empirical evidence in an urban public-space context for these ideas. The authors observed that when the environment supports older adults’ needs, it bolsters their sense of autonomy and attachment. Conversely, if an environment is inconvenient or hostile, it can undermine an elder’s confidence and desire to remain there, a phenomenon consistent with the environmental stress model [

85]. By showing that supportive physical settings amplify competence yet must be complemented by informal, people-centered infrastructures to secure lasting bonds, AiPA provides a trans-disciplinary bridge linking environmental-press theory with contemporary scholarship on social infrastructure. As such, it furnishes planners with a diagnostic lens that targets emotional as well as physical outcomes of age-friendly interventions.

To complement the theoretical discussion, we offer several methodological reflections. Hierarchical regression was strategically chosen for its capacity to quantify the incremental explanatory power of grouped variables, revealing the distinct contributions of physical, behavioral, physiological, and psychological domains to AiPA. To verify the robustness of our hierarchical model, we performed several diagnostic tests, including multicollinearity checks (all VIF values < 3.1), residual normality assessments, and sensitivity analyses using bootstrap methods (1000 samples), confirming model stability and the reliability of findings. In addition, the block-wise hierarchy observed in our regression (physical ≈ 5% < human-factor ≈ 4% < behavior ≈ 15% < psychology ≈ 60%) should not be read as evidence that the first two domains are negligible. Rather, their comparatively low direct contributions imply that their influence is channeled through higher-order mechanisms. Conceptually, the built environment furnishes affordances that scaffold social interaction; those interactions, in turn, consolidate emotional bonds, while sensory engagement provides the perceptual glue that links experience to meaning. Put differently, Environment→Behavior→Perception→Psychology→AiPA may constitute a layered causal chain, with each tier amplifying or dampening the effect inherited from the previous one.

While hierarchical regression effectively demonstrates each domain’s relative contribution, it remains limited in its ability to clarify complex interrelationships among variables. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), as a complementary analytical method, is particularly suited to addressing this limitation, as it simultaneously estimates multiple mediating and indirect pathways among latent constructs. In a preliminary SEM analysis from related ongoing research, we found initial evidence suggesting that physical environmental attributes influence AiPA primarily through behavioral and psychological mediators, rather than through direct effects alone. Specifically, behavioral engagement appears to play a nuanced mediating role, while psychological factors, especially place attachment, significantly mediate and strengthen these relationships. Although these SEM results are preliminary and are therefore not tabulated in the present article, they lend empirical support to the mediation logic implied by our regression hierarchy. Given the exploratory nature of these initial findings, although a full SEM analysis exceeds the current scope of this manuscript, future research employing comprehensive SEM frameworks is strongly recommended to rigorously test these mediation pathways and refine the theoretical understanding of AiPA in high-density urban environments.

5.6. Reflections from Qualitative Insights

Although the in-depth interviews in this study involved 12 older adults (approximately 20% of the survey sample), their narratives offer valuable qualitative insights that complement the quantitative findings. These subjective accounts highlight the emotional underpinnings of place attachment and aging-in-place experiences in Macau’s high-density public spaces. Respondents commonly described emotional bonds rooted in long-term residence, intergenerational ties, and stable social networks, indicating that attachment is shaped not only by the physical environment but also by accumulated life experiences and social embeddedness.

At the broadest level, the regression shows that psychological factors and social behavior dominate the variance in AiPA (β_place attachment = 0.67; β_social behavior = 0.81). Interviewees echoed this primacy: they repeatedly framed neighborhood plazas as “second living rooms” where long-standing acquaintances provide emotional security, and where “seeing familiar faces every morning” is perceived as a guarantee of continued autonomy. Thus, the qualitative testimonies reinforce the quantitative finding that social embed-ded-ness is the principal engine of AiPA. A second point of convergence concerns sensory engagement. Longer gaze duration within AOIs and higher visit counts were modest but significant predictors of attachment (β ≈ 0.09). Participants independently narrated that visual cues such as “hand-painted tiles” or “ancient banyans” anchor memories and invite repeat visitation. These statements give phenomenological substance to what the eye-tracking metrics register only in the abstract.

Not all linkages are confirmatory, however. They also supplied a counterview to one statistical result: while the model assigns a negative weight to nature-attachment (β = −0.45), interviewees repeatedly stressed that Macau and existing pocket parks are “too small, leaving their longing for everyday activities and greenery unsatisfied rather than absent, hence the negative coefficient reflects spatial scarcity, not a lack of ecological affinity. A similar nuance arises for age-friendly accessibility. Quantitatively, the index shows a small negative association with AiPA (β = −0.06), yet elders rarely complained about ramps or handrails in conversation. Instead, they lamented construction noise, crowding, and the loss of “resting niches.” The implication is that once basic accessibility thresholds are met, incremental hardware upgrades matter less than the experiential quality of the space—an insight that refines what the purely numerical coefficient can tell.

Taken together, these points illustrate a complementary relationship between methods: quantitative analysis identifies the structural weight of each domain, while qualitative narratives clarify the meanings, contingencies, and blind spots behind those weights. Where the two strands concur, confidence in the findings is strengthened; where they diverge, fresh hypotheses and design cues emerge. In this sense, the mixed-methods synthesis not only validates but also extends the explanatory reach of the study, offering a better understanding of how Macau’s elders come to— or decline to—age in place.

5.7. Limitations

The authors note that this cross-sectional, hierarchical regression approach only reveals direct associations. The model identifies key predictors of AiPA, but cannot test indirect paths, such as environmental influence via neighborhood satisfaction. From an architectural standpoint, it is important to note that apparent low effects in data may reflect methodological limitations or underreporting by participants, rather than a true lack of environmental influence [

51,

52]. Future research should therefore employ SEM or path analysis, as performed in other aging-in-place studies [

54], to disentangle these chains of influence. The Macau-specific context limits generalizability, but future work could explore how digital features shape place attachment. Similarly, intergenerational dynamics and institutional support were outside the scope of our analysis but are likely important for holistic aging-friendly communities. Nevertheless, the mixed-methods, multisource data offer a rich, convergent picture of AiPA processes, paving the way for broader validation in diverse urban aging settings.

6. Conclusions

In high-density urban environments like Macau, the ability of older adults to age in place comfortably and meaningfully is less about any single physical feature and more about the synergy between people and their environment. This research introduced the Aging-in-Place Attachment to understand that synergy. By examining physical space, observed behaviors, sensory responses, and psychological bonds in concert, this study demonstrated that older adults’ attachment to place–and their commitment to continue living in their community–arises primarily from the emotional and social fulfillment they derive there. Place attachment and behavioral intention proved to be decisive factors in our empirical model, reflecting the deep human need for belonging and purpose. Social interactions and active engagement in community life were shown to greatly amplify these attachments. In contrast, physical environmental attributes played a more supportive role: they were necessary to enable engagement but, by themselves, accounted for only a small portion of the attachment motivation. Even human-factor cues mattered insofar as they facilitated those positive experiences and feelings. Together, these findings confirm that AiPA is a multilayered construct–one that is built on the foundation of a welcoming environment, but ultimately crowned by the edifice of social connection and emotional significance.

From an architectural and urban planning standpoint, the study provides evidence-based guidance for creating age-friendly cities. While an accessible, safe, and aesthetically pleasing physical environment is important, it is only the beginning. Equally crucial is designing and managing public spaces in ways that encourage social interaction, ongoing participation, and a sense of ownership among older residents. This could mean incorporating flexible spaces for community events, comfortable seating arrangements that facilitate conversation, elements of local culture and history that instill pride and identity, and green or tranquil spots that offer psychological relief in a dense cityscape. By nurturing these conditions, architects and planners can help forge the emotional bonds that truly anchor seniors in their communities. The concept of AiPA introduced here offers a practical framework for evaluating such interventions: success can be measured not just by usage statistics, but by whether older people feel more attached and committed to aging in their place as a result.

This study extended traditional place attachment theory into the gerontological realm, demonstrating that aging-in-place attachment can be empirically measured and modeled. In doing so, this study bridged disciplines, linking environmental psychology’s insights on emotional bonds, sociology’s emphasis on community interaction, and architecture’s focus on space and form. The high explanatory power of the integrated model (over 80%) suggests that comprehensive, interdisciplinary approaches are indeed capable of capturing the complex reality of aging in place better than siloed analyses. The findings reinforce the idea that successful aging in an urban context is a collaborative achievement between people and their environments. For policymakers, this means that efforts to help seniors age in place should be multifaceted, combining physical improvements with social programs and psychological support.

In conclusion, aging-in-place attachment encapsulates the idea that home for older adults extends beyond the four walls of their dwelling to the wider community milieu that gives them joy, security, and a sense of belonging. This study in Macau’s public spaces has empirically validated this concept and highlighted the predominance of human-centered factors in cultivating attachment. Moving forward, this study envisions that city designers and researchers will take up this mantle, exploring new ways to strengthen the emotional connection between older adults and their neighborhoods. As cities worldwide grapple with rapid population aging, adopting an AiPA lens can help ensure that urban environments are not just livable, but lovable for those in their later years. By investing in both the social hearts and the physical bones of communities, we can empower more elders to not only remain in place, but also to truly thrive in place for the rest of their lives.