Sustainable Finance: Bridging Circular Economy Goals and Financial Inclusion in Developing Economies

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What specific mechanisms within sustainable finance drive circular economy adoption in resource-constrained settings?

- (2)

- What role does financial inclusion play in enabling broader participation in sustainable development initiatives?

- (3)

- How do policy and infrastructural gaps impede sustainable finance and CE integration, and what strategies have been effective in overcoming them?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Finance in Developing Economies

2.2. Circular Economy Principles and Financial Investments

2.3. Financial Inclusion as a Catalyst for Sustainability

2.4. Integration of Sustainable Finance, Circular Economy, and Financial Inclusion

Takeaway

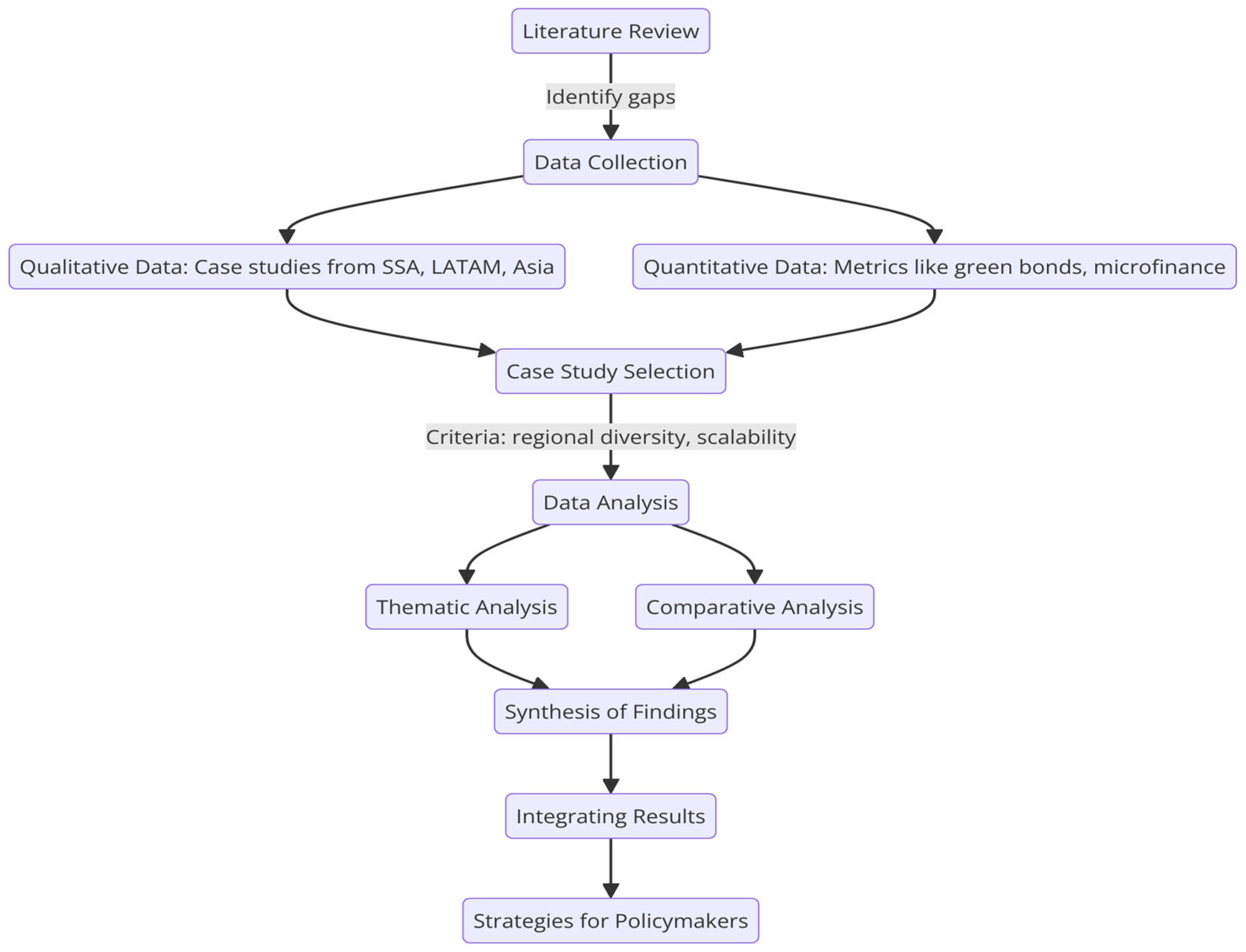

3. Methodology

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Results

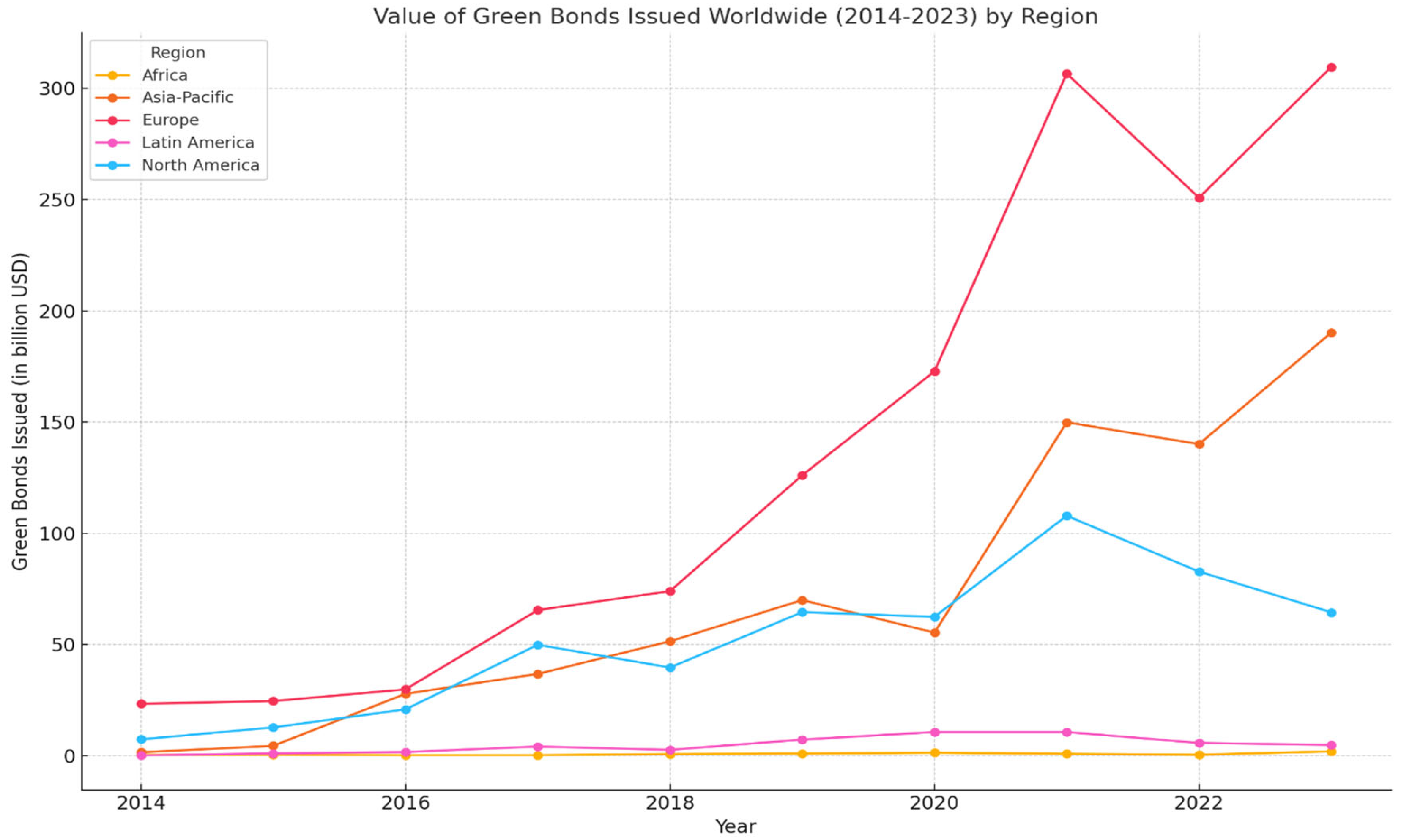

4.1.1. Regional Trends in Green Bond Issuance

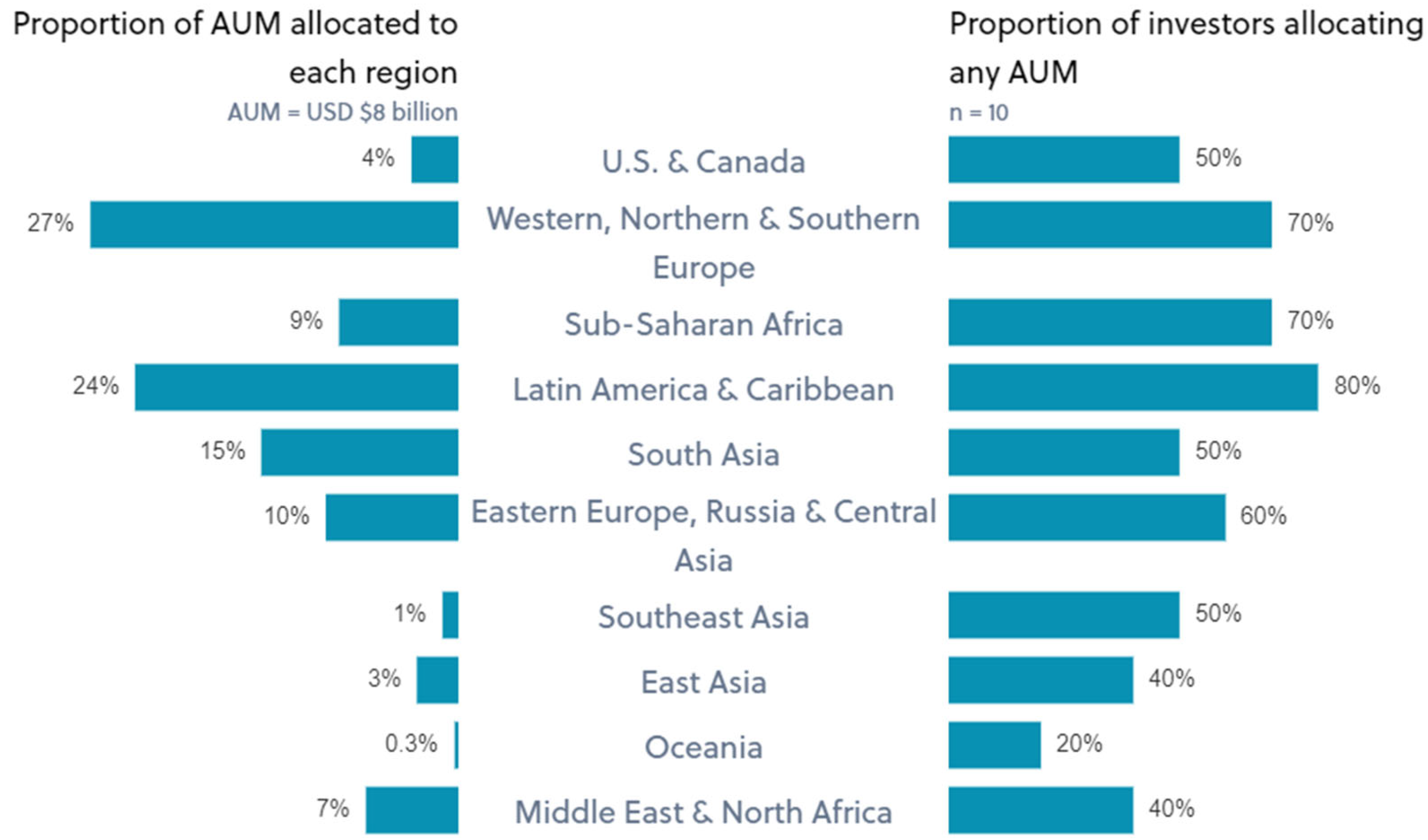

Impact Investing and Socioenvironmental Goals

- Europe (27%) leads in impact investing, driven by robust policies such as the EU Circular Economy Action Plan, which promotes waste reduction, recycling, and sustainable production.

- Latin America (24%) benefits from opportunities in sustainable agriculture, water management, and deforestation mitigation.

- Emerging markets: Sub-Saharan Africa (9%), South Asia (15%), and Southeast Asia (1%) receive lower AUM shares due to perceived risks, limited investment frameworks, and infrastructure challenges. However, these regions have untapped potential in waste management, resource-efficient agriculture, and technology-enabled circular practices.

- Oceania (0.3%) and MENA (7%) see minimal allocations despite opportunities in resource management and sustainable manufacturing.

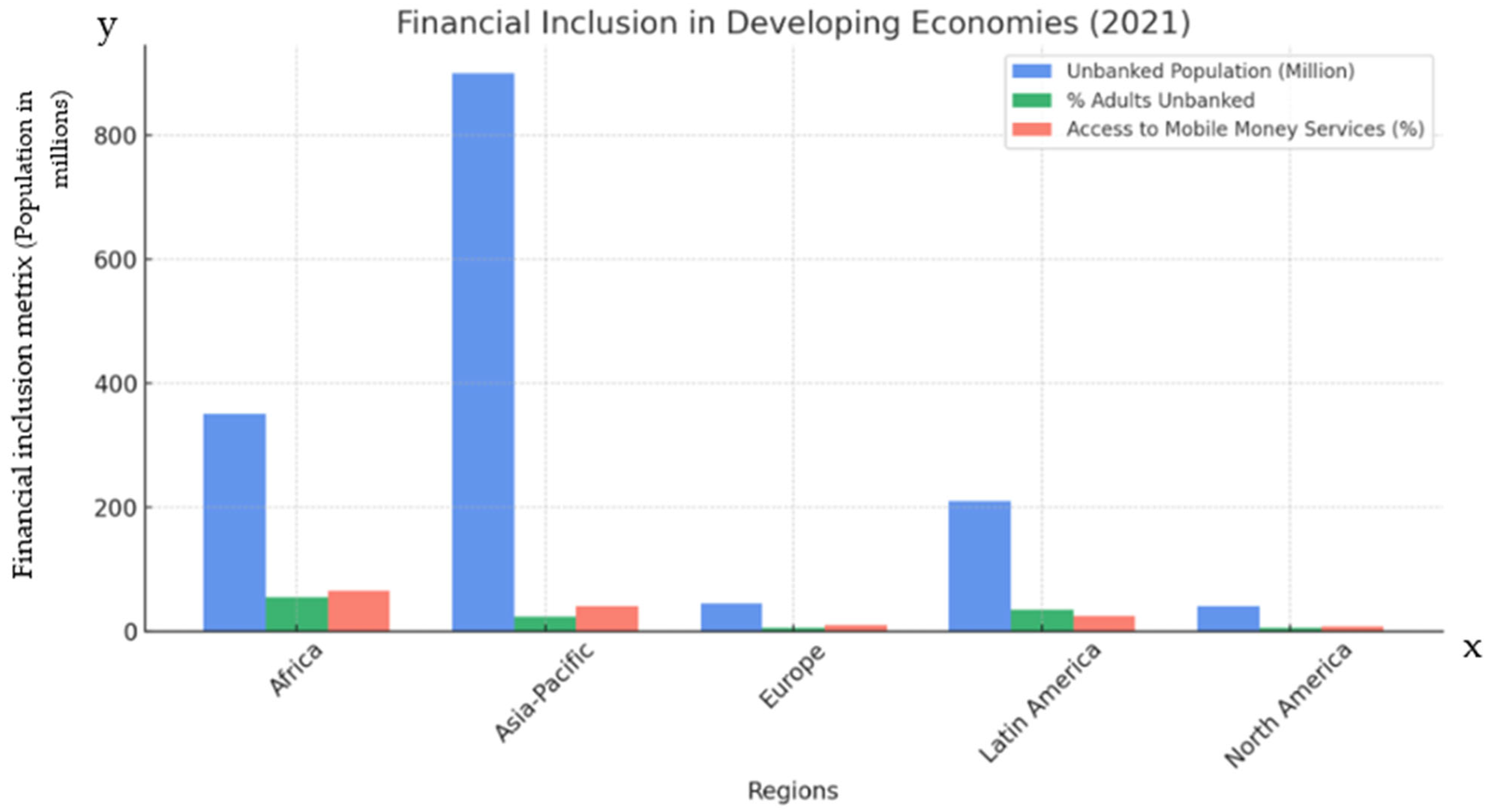

4.1.2. Financial Inclusion in Sustainable Development and CE Initiatives

4.1.3. Comparative Insights of Finance, Green Bonds, and Circular Economy (CE)

4.1.4. Challenges in Implementing Sustainable Finance and CE Frameworks in Developing Economies

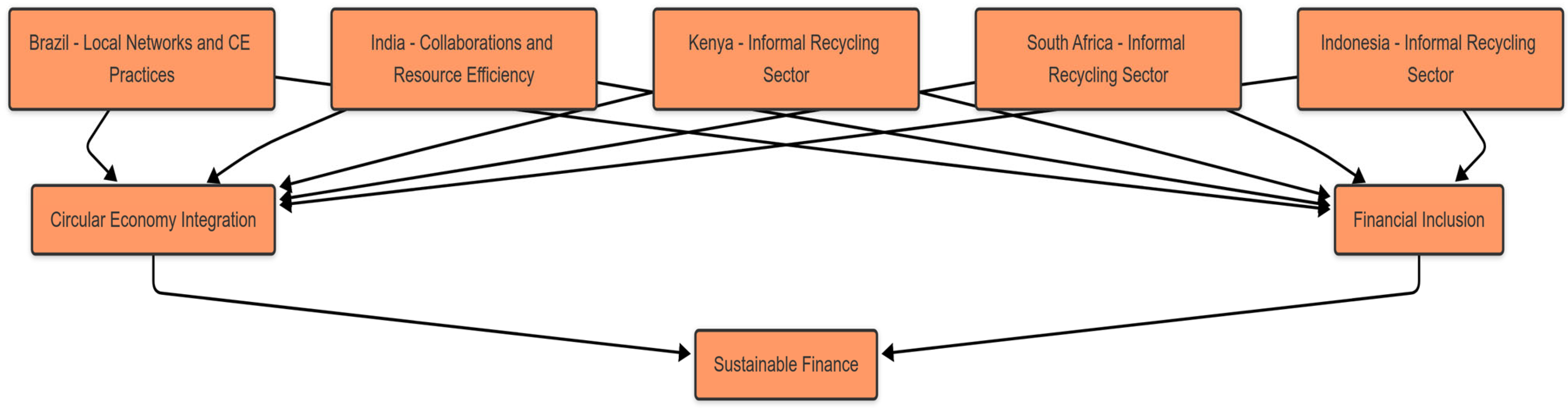

4.1.5. Integrated Solutions for Scaling CE Initiatives: Case Studies of Innovative Practices

Brazil—Local Networks and Circular Economy Practices

- Internal environmental management. Businesses prioritize waste reduction, energy efficiency, and water conservation, laying the groundwork for sustainable production.

- Ecological design. Enterprises in sectors such as furniture and textiles emphasize reusable and biodegradable materials, aligning with consumer demand for sustainable products. Local artisans play a critical role in driving this movement.

- Investment recovery. By recycling and repurposing waste, businesses find new revenue streams, reducing costs while improving resource efficiency.

India—Collaborations and Resource Efficiency in SMEs

Kenya, South Africa, and Indonesia—Circular Economy and Informal Recycling

4.2. Discussion

4.2.1. Green Bonds and Regional Disparities

4.2.2. Microfinance and Financial Inclusion

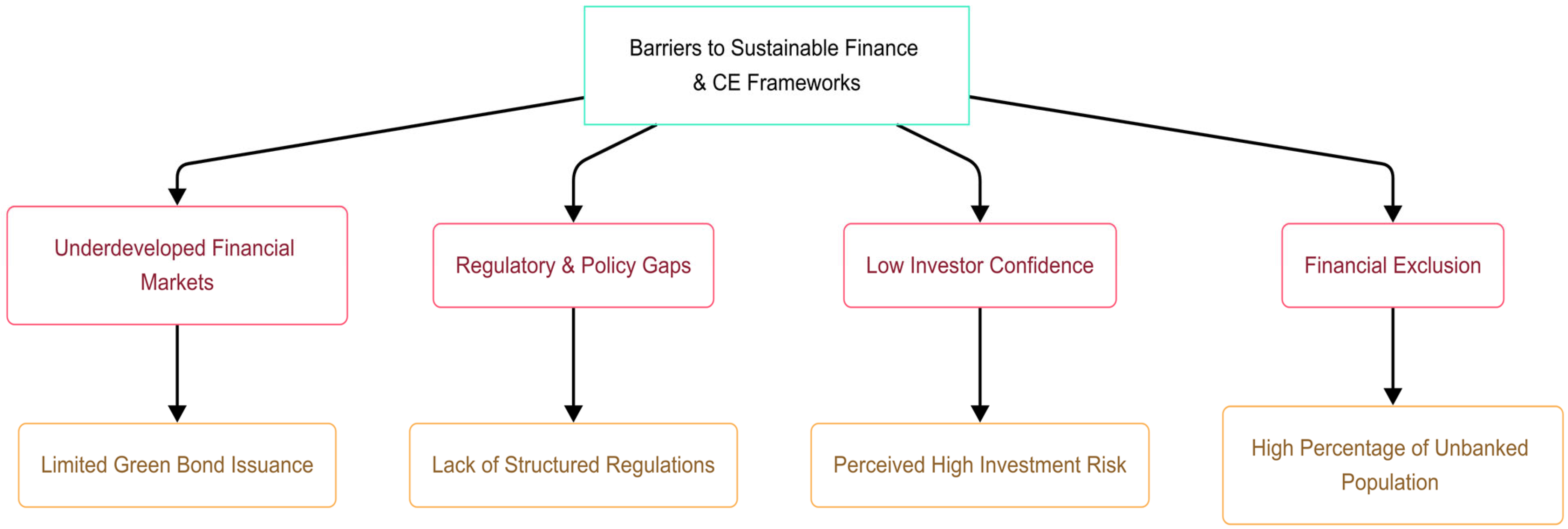

4.2.3. Barriers to Sustainable Finance and CE Integration

- Underdeveloped financial markets. As shown in Table 1, green bond issuance in regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America remains limited, restricting access to capital for sustainability projects.

- Regulatory gaps. Unlike Europe, where structured policies such as the EU’s Green Deal incentivize green finance, many developing regions lack the regulatory certainty needed to attract investors.

- Low investor confidence. Figure 3 highlights that despite high investor interest in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, actual investment flows remain low due to perceived risks and governance challenges.

- Financial exclusion. Limited access to formal banking systems continues to hinder the growth of small-scale CE enterprises, particularly in rural and underserved areas, as demonstrated in Figure 4.

4.2.4. Integrated Solutions and Policy Recommendations

5. Conclusions

5.1. Contribution of the Paper

5.2. Recommendations

- 1.

- Promoting Green Bonds. Governments should incentivize the issuance of green bonds to finance CE projects by offering tax breaks, subsidies, and favorable regulations. Green bonds provide direct funding for sustainable infrastructure, renewable energy, and resource-efficient technologies. Fiscal incentives reduce capital costs, encouraging public and private investments in CE initiatives, particularly in underdeveloped regions where funding barriers persist.

- 2.

- Supporting Microfinance for Circular Enterprises. Enhanced regulatory frameworks can expand microfinance to support small-scale CE enterprises. Microfinance plays a key role in financial inclusion, enabling marginalized groups to access funding for ventures such as recycling, waste management, and upcycling. Tailoring microfinance programs to incorporate sustainability criteria can help small businesses adopt environmentally responsible practices, driving economic growth and environmental protection.

- 3.

- Developing Impact Investing Ecosystems. Governments and financial institutions should foster impact-investing ecosystems to channel capital into CE initiatives. Impact investing, which combines financial returns with social and environmental benefits, is well-suited to CE projects. Creating supportive regulatory frameworks, incentives, and platforms connecting investors with CE businesses can scale investments in renewable energy, sustainable agriculture, and eco-friendly manufacturing.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Economic Forum. What Are Green Bonds, and How Do They Help Fight Climate Change? Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/11/what-are-green-bonds-climate-change/ (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Circle Economy. Circularity Gap Report 2024: Global. European Circular Economy Stakeholder Platform. Available online: https://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/en/knowledge/circularity-gap-report-2024 (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Liyanage, S.I.H.; Netswera, F.G.; Motsumi, A. Insights from EU policy framework in aligning sustainable finance for sustainable development in Africa and Asia. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2021, 11, 459–470. [Google Scholar]

- Ziolo, M.; Filipiak, B.Z.; Bąk, I.; Cheba, K.; Tîrca, D.M.; Novo-Corti, I. Finance, sustainability and negative externalities. An overview of the European context. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziolo, M.; Bak, I.; Cheba, K. The role of sustainable finance in achieving sustainable development goals: Does it work? Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2021, 27, 45–70. [Google Scholar]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy—A new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, O.W.; Basile, I.; De Kemp, A.; Gotz, G.; Lundsgaarde, E.; Orth, M. Blended Finance Evaluation: Governance and Methodological Challenges; OECD Development Co-operation Working Papers No. 51; OECD: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Timer, S.; Raza, S.A. Nonlinear relationship between financial inclusion and inclusive economic development in developed economies: Evidence from panel smooth transition regression model. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2023, 50, 1022–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affandi, H.; Malik, Q.A. Financial Inclusion between Financial Innovation and Economic Growth: A Study of Lower Middle-Income Economies. J. Account. Financ. Emerg. Econ. 2021, 7, 913–920. [Google Scholar]

- Khera, P.; Ng, S.; Ogawa, S.; Sahay, R. Measuring digital financial inclusion in emerging market and developing economies: A new index. Asian Econ. Policy Rev. 2022, 17, 213–230. [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen, J.; Honkasalo, A.; Seppälä, J. Circular economy: The concept and its limitations. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 143, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorelli, M. What do we mean by sustainable finance? Assessing existing frameworks and policy risks. Sustainability 2021, 13, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleknevičienė, V.; Bendoraitytė, A. Role Of Green Finance in Greening the Economy: Conceptual Approach. Cent. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2023, 12, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakovlev, I.A.; Nikulina, S.I. Indonesia’s Strategy for Sustainable Finance. Master’s Thesis, Finansovyy Zhurnal, Moscow, Russia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Machingambi, J. The Impact of Microfinance on The Sustainability of ‘Poor’ Clients: A Conceptual Review. J. Entrep. Innov. 2020, 1, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawhouser, H.; Cummings, M.; Newbert, S.L. Social impact measurement: Current approaches and future directions for social entrepreneurship research. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 43, 82–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengo, I.; Boni, L.; Sancino, A. EU financial regulations and social impact measurement practices: A comprehensive framework on finance for sustainable development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, P.; Anantharaman, M.; Anggraeni, K.; Foxon, T.J. The circular economy and the Global South. In The Circular Economy and the Global South; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Which Country Is Leading the Circular Economy Shift? Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/articles/which-country-is-leading-the-circular-economy-shift (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- Murray, A.; Skene, K.; Haynes, K. The circular economy: An interdisciplinary exploration of the concept and application in a global context. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, F.; Lehne, J. A wider circle? The circular economy in developing countries. In Proceedings of the Circular Economy Conference, London, UK, 5 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ness, D. Sustainable urban infrastructure in China: Towards a Factor 10 improvement in resource productivity through integrated infrastructure systems. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2008, 15, 288–301. [Google Scholar]

- Dewick, P.; Bengtsson, M.; Cohen, M.J.; Sarkis, J.; Schröder, P. Circular economy finance: Clear winner or risky proposition? J. Ind. Ecol. 2020, 24, 1192–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahel, W.R. The circular economy. Nature 2016, 531, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieder, M.; Rashid, A. Towards circular economy implementation: A comprehensive review in the context of the manufacturing industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 115, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabula, J.B.; Han, D.P. Financial literacy of SME managers on access to finance and performance: The mediating role of financial service utilization. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2018, 9, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Global Findex Database 2021: Financial Inclusion, Digital Payments, and Resilience. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/globalfindex (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Ranabahu, N.; Wickramasinghe, A. Sustainable Leadership in Microfinance: A Pathway for Sustainable Initiatives in Micro and Small Businesses? Sustainability 2022, 14, 5167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI). Financing Circularity: Demystifying Finance for the Circular Economy. Available online: https://www.unepfi.org/publications/financing-circularity/ (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Ashraf, A.; Billah, M.; Ayoob, M.; Zulfiqar, N. Analyzing the impact of microfinance initiatives on poverty alleviation and economic development. Rev. Appl. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2024, 7, 431–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Unveiling the Global Findex Database 2021: Five Charts. World Bank Blogs. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/developmenttalk/unveiling-global-findex-database-2021-five-charts (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L.; Singer, D.; Ansar, S. The Global Findex Database 2021: Financial Inclusion, Digital Payments, and Resilience in the Age of COVID-19; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, F.; Lehne, J.; Wellesley, L. An Inclusive Circular Economy: Priorities for Developing Countries; The Royal Institute of International Affairs, Chatham House: London, UK, 2019; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency. Monitoring Report on Progress Towards the 8th EAP Objectives—2023 Edition. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/monitoring-progress-towards-8th-eap-objectives (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Camilleri, M.A. Closing the loop for resource efficiency, sustainable consumption and production: A critical review of the circular economy. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Adelaja, A.O.; Umeorah, S.C.; Abikoye, B.E.; Nezianya, M.C. Advancing financial inclusion through fintech: Solutions for unbanked and underbanked populations. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 23, 427–438. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, B.; Kumar, L.; Kumar, A.; Kumari, R.; Tagar, U.; Sassanelli, C. Green finance in circular economy: A literature review. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 16419–16459. [Google Scholar]

- Sepetis, A. Sustainable finance and circular economy. In Circular Economy and Sustainability; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 207–226. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C. Green finance and investment: Emerging trends in sustainable development. J. Appl. Econ. Policy Stud. 2024, 6, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Value of Green Bonds Issued Worldwide from 2014 to 2023, by Region (In Billion U.S. Dollars). Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1294449/value-of-green-bonds-issued-worldwide-by-region (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Global Impact Investing Network, “About the GIIN.” (Online). Available online: https://thegiin.org/about/ (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN). The 2023 GIINsight Series: A Comprehensive Overview of Impact Investing Activity and Impact Measurement & Management Practice. Available online: https://thegiin.org/publication/research/2023-giinsight-series (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- World Bank. COVID-19 Boosted the Adoption of Digital Financial Services. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2022/07/21/covid-19-boosted-the-adoption-of-digital-financial-services (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Mejía, D.; Saavedra, M. Financial Inclusion in Latin America: How Far We Have Come. CAF—Development Bank of Latin America. Available online: https://www.caf.com/en/blog/financial-inclusion-in-latin-america-how-far-we-have-come (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- FinDev Gateway. Financial Inclusion: Global Overview. Available online: https://www.findevgateway.org/region/financial-inclusion-global-overview (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Silva, F.C.; Shibao, F.Y.; Kruglianskas, I.; Barbieri, J.C.; Sinisgalli, P.A.A. Circular economy: Analysis of the implementation of practices in the Brazilian network. Rev. Gestão 2019, 26, 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, J.L.; Chiwenga, K.D.; Ali, K. Collaboration as an enabler for circular economy: A case study of a developing country. Manag. Decis. 2021, 59, 1784–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | Financial Inclusion (%) * | Green Bond Issuance ($B) * | Prevalence of CE Practices * |

|---|---|---|---|

| East Asia and the Pacific | 76% | Significant issuance | China has been a pioneer in CE, integrating it into policy since the early 2000s |

| Europe and Central Asia | 78% | Leading region | The EU has implemented comprehensive CE policies, including the Circular Economy Action Plan |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 73% | Emerging market | CE initiatives are growing, focusing on waste reduction and resource efficiency |

| Middle East and North Africa | 44% | Limited issuance | CE adoption is in the early stages, with increasing interest in sustainable development |

| South Asia | 68% | Minimal issuance | CE practices are developing, with efforts to integrate sustainability into economic planning |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 55% | Nascent market | CE initiatives are emerging, focusing on recycling and sustainable resource management |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Taera, E.G.; Lakner, Z. Sustainable Finance: Bridging Circular Economy Goals and Financial Inclusion in Developing Economies. World 2025, 6, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6020044

Taera EG, Lakner Z. Sustainable Finance: Bridging Circular Economy Goals and Financial Inclusion in Developing Economies. World. 2025; 6(2):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6020044

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaera, Edosa Getachew, and Zoltan Lakner. 2025. "Sustainable Finance: Bridging Circular Economy Goals and Financial Inclusion in Developing Economies" World 6, no. 2: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6020044

APA StyleTaera, E. G., & Lakner, Z. (2025). Sustainable Finance: Bridging Circular Economy Goals and Financial Inclusion in Developing Economies. World, 6(2), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6020044