Muslim Working Women: The Effect of Cultural Values and Degree of Religiosity on the Centrality of Work, Family, and Other Life Domains

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Islamic Work Ethic (IWE)

2.2. The Arab Muslim Minority in Israel

2.3. Centrality and Ranking of Life Domains

2.4. Relationship Between Life Domain Centrality and Religiosity Among Muslim Women in Israel

2.4.1. Work Centrality

2.4.2. Family Centrality

2.4.3. Leisure Centrality

2.4.4. Community Centrality

3. Method

3.1. The Sample

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Centrality of Life Domains

- Leisure (e.g., hobbies, sports, entertainment, and friendships);

- Community (e.g., volunteer organizations, trade unions, and political organizations);

- Work;

- Religion (e.g., religious activities and beliefs);

- Family.

3.2.2. Degree of Religiosity

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions, Research Limitations, and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yucel, D.; Chung, H. Working from home, work–family conflict, and the role of gender and gender role attitudes. Community Work Fam. 2023, 26, 190–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Hasan Nabwani, O.; Sharabi, M. Predictors of work-family conflict among married women in Israel. Isr. Aff. 2023, 29, 257–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharabi, M.; Kay, A. The relative centrality of life domains among secular, Traditional and Religious (Haredi) men in Israel. Community Work Fam. 2021, 24, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerkes, M.A.; Roeters, A.; Baxter, J. Gender differences in the quality of leisure: A cross-national comparison. Community Work Fam. 2020, 23, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, Y.; Khattab, N. Women, labor market outcomes and religion: Evidence from the British labor market. Rev. Soc. Econ 2022, 80, 283–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattab, N.; Hussein, S. Can religious affiliation explain the disadvantage of Muslim women in the British labor market? Work Employ. Soc. 2018, 32, 1011–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattab, N.; Miaari, S.; Mohamed-Ali, M. Visible minorities in the Canadian Labour Market: Disentangling the effect of religion and ethnicity. Ethnicities 2020, 20, 1218–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samani, S.; Marinova, D. Muslim Women in the Economy; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaunt, R. Blessed is he who has not made me a woman: Ambivalent sexism and Jewish religiosity. Sex Roles 2012, 6, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taşdemir, N.; Sakallı-Uğurlu, N. The relationships between ambivalent sexism and religiosity among Turkish university students. Sex Roles 2010, 62, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifeen, S.R.; Gatrell, C. A blind spot in organization studies: Gender with ethnicity, nationality and religion. Women Bus. Lead. 2013, 28, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, L.; Madsen, S.R.; Davis, J. Women in business leadership: A comparative study of countries in the Gulf Arab states. Int. J. Cross Cult. Manag. 2015, 15, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almond, G.; Appleby, R.S.; Sivan, E. Strong Religion: The Rise of Fundamentalism around the World; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dubin, R.; Hedley, A.R.; Taveggia, T.C. Attachment to work. In Handbook of Work, Organization and Society; Dubin, R., Ed.; Rand McNally: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976; pp. 281–341. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2777828 (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- MOW-International Research Team. The Meaning of Work: An International View; Academic Press: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Méda, D. The Future of Work: The Meaning and Value of Work in Europe; ILO Research Paper No. 18; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://hal.science/hal-01616579 (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Carbado, D.W.; Crenshaw, K.W.; Mays, V.M.; Tomlinson, B. Intersectionality: Mapping the Movements of a Theory1. Du Bois Rev. Soc. Sci. Res. Race 2013, 10, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Zamor, J.C. The global wave of refugees and migrants: Complex challenges for European policy makers. Public Organ. Rev. 2017, 17, 581–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miaari, S.H.; Khattab, N.; Sabbah-Karkabi, M. Obstacles to Labour Market Participation among Palestinian-Arab Women in Israel. Int. Labor Rev. 2023, 162, 587–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrench, J. Diversity Management and Discrimination: Immigrants and Ethnic Minorities in the EU; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parboteeah, P.K.; Hoegl, M.; Cullen, J.B. Religious dimensions and work obligation: A country institutional profile mode. Hum. Relat. 2019, 62, 119–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Culture matters: National value cultures, sources, and consequences. In Understanding Culture: Theory, Research and Application; Chiu, C.Y., Hong, Y.Y., Shavitt, S., Wyer, R.S., Jr., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharabi, M. Ethno-Religious Groups Work Values and Ethics: The Case of Jews, Muslims and Christians in Israel. Int. Rev. Sociol. 2018, 28, 171–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amara, M.; Schnell, I. Identity repertoires among Arabs in Israel. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2004, 30, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shdema, I.; Martin, D.; Abu-Asbe, K. Exposure to the majority social space and residential place identity among minorities: Evidence from Arabs in Israel. Urban Geogr. 2021, 42, 507–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, R.D.; Kemmelmeier, M. Weber revisited: A cross-national analysis of religiosity, religious culture, and economic attitudes. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2011, 42, 1406–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarakeshwar, N.; Stanton, J.; Pargament, K.I. Religion: An overlooked dimension in cross-cultural psychology. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2003, 34, 377–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.J.; Al-Owaihan, A. Islamic work ethic: A critical review. Cross Cult. Manag. Int. J. 2008, 15, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, D.A. The Islamic work ethic as a mediator of the relationship between locus of control, role conflict and role ambiguity–A study in an Islamic country setting. J. Manag. Psychol. 2000, 15, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budd, J. The Thought of Work; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rosso, B.D.; Dekas, K.H.; Wrzesniewski, A. On the meaning of work: Theoretical integration and review. Res. Organ. Behav. 2010, 30, 91–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, T.; Korczynski, M. Sociology, Work and Industry, 5th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, S.; Hardy, C. Critical discourse analysis and identity: Why bother? Crit. Disc. Stud. 2004, 1, 225–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.J.; Al-Kazemi, A.A. Islamic work ethic in Kuwait. Cross Cult. Manag. Int. J. 2007, 14, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouma, G.; Haidar, A.; Nyland, C.; Smith, W. Work, religious diversity and Islam. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2003, 41, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism; Scribner: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Linando, J.A.; Tumewang, Y.K.; Nahda, K.; Nurfauziah. The dynamic effects of religion: An exploration of religiosity influences on Islamic work ethic over time. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2181127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.C.; Tipu, S.A. An empirical alternative to Sidani and Thornberry’s (2009) “current Arab work ethic”: Examining the multidimensional work ethic profile in an Arab context. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Statistical Abstract of Israel; Government Printing Office: Jerusalem, Israel, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.D. Ethnicity and nationalism. In The SAGE Handbook of Nations and Nationalism; Delanty, G., Kumar, K., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2006; pp. 169–179. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Atawneh, M.; Ali, N. Islam in Israel: Muslim Communities in Non-Muslim States; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hatina, M.; Al-Atawneh, M. (Eds.) Muslims in a Jewish State: Religion, Politics, Society; Hakibutz Hameuhad: Tel-Aviv, Israel, 2018. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, I.; Abu Baker, H.; Saar, A. Arab Society in Israel; Open University: Raanana, Israel, 2012. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Sharabi, M. Work ethic among Jews and Muslims: The effect of religiosity degree and demographic factors. Sociol. Perspect. 2017, 60, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ghannam, R.A. Analytical study of women’s participation in economic activities in Arab societies. Equal Oppor. Int. 2002, 21, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharabi, M.; Shdema, I.; Abboud-Armaly, O. Nonfinancial employment commitment among Muslims and Jews in Israel: Examination of the core–periphery model on majority and minority groups. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2020, 43, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin-Epstein, N.; Semyonov, M. Modernization and Subordination: Palestinian Women in the Israeli Labor Force. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 1992, 8, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, H. Education and employment among young Arabs. In State of National Report: Society, Economics and Policy; Weisz, V., Ed.; Taub Center: Jerusalem, Israel, 2017; pp. 221–262. [Google Scholar]

- Shdema, I. Arabs’ workforce participation in Israel at a Single Municipality Scale. In Palestinians in the Israeli Labor Market: A Multi-Disciplinary Approach; Khattab, N., Miaari, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013; pp. 241–262. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, V.; Yonay, Y.P. Facing Barriers: Palestinian Women in a Jewish-Dominated Labor Market; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Rabia-Queder, S. The paradox of professional marginality among Arab-Bedouin women. Sociology 2017, 51, 1084–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonay, Y.P.; Yaish, M.; Kraus, V. Religious heterogeneity and cultural diffusion: The impact of Christian neighbors on Muslim and Druze women’s participation in the labor force in Israel. Sociology 2015, 49, 660–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westwood, R.; Lok, P. The meaning of work in Chinese contexts a comparative study. Int. J. Cross-Cult. Manag. 2003, 3, 139–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharabi, M.; Harpaz, I. Changes in Work Centrality and Other Life Areas in Israel: A Longitudinal Study. J. Hum. Values 2007, 13, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, S.D.; Hikspoors, F.J. New work values in theory and in practice. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 1995, 47, 441–455. [Google Scholar]

- Kuchinke, K.P.; Ardichvili, A.; Borchert, M.; Rozanski, A. The meaning of working among professional employees in Germany, Poland and Russia. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2009, 33, 104–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchinke, K.P.; Ardichvili, A.; Borchert, M.; Cornachione, E.B.; Cseh, M.; Kang, H.-S.; Oh, S.Y.; Rozanski, A.; Tynaliev, U.; Zav’jalova, E. Work meaning among mid-level professional employees: A study of the importance of work centrality and extrinsic and intrinsic work goals in eight countries. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2011, 49, 264–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharabi, M. The relative centrality of life domains among Jews and Arabs in Israel: The effect of culture, ethnicity, and demographic variables. Community Work Fam. 2014, 17, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, D.A. Islamic work ethic—A moderator between organizational commitment and job satisfaction in a cross-cultural context. Pers. Rev. 2001, 30, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidani, Y.M. Muslim Women at Work; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korotayev, A.V.; Issaev, L.M.; Shishkina, A.R. Female labor force participation rate, Islam, and Arab culture in cross-cultural perspective. Cross-Cult. Res. 2015, 49, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elci, M. Effect of manifest needs, religiosity and selected demographics on hard working: An empirical investigation in Turkey. J. Int. Bus. Res. 2007, 6, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Aygün, Z.K.; Arslan, M.; Güney, S. Work values of Turkish and American university students. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 80, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spierings, N. Women’s Employment in Muslim Countries: Patterns of Diversity; Springer: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Asbah, K.M.; Heilbrunn, S. Patterns of entrepreneurship of Arab women in Israel. J. Enterpris. Commun. People Places Glob. Econ. 2011, 5, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulik, L.; Rayyan, F. Relationships between dual-earner spouses, strategies for coping with home–work demands and emotional well-being: Jewish and Arab-Muslim women in Israel. Community Work Fam. 2006, 9, 457–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellekens, J.; Atrash, A.A. Religiosity and marital fertility among Muslims in Israel. Demogr. Res. 2018, 39, 911–926. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26585355 (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Méda, D.; Vendramin, P. Reinventing Work in Europe: Value, Generations and Labour; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Campbell, S.M.; Hoffman, B.J.; Lance, C.E. Generational differences in work values: Leisure and extrinsic values increasing, social and intrinsic values decreasing. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 1117–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veal, A.J. Leisure and the Future; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walseth, K.; Amara, M. Islam and Leisure. In The Palgrave Handbook of Leisure Theory; Spracklen, K., Lashua, B., Sharpe, E., Swain, S., Eds.; Palgrave-Macmillan: London, UK, 2017; pp. 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William, H.M.; Mason, S. Leisure in three middle eastern countries. World Leis. J. 2003, 45, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C. Individualism and Collectivism; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shdema, I.; Martin, D. Place identity among indigenous minorities: Lessons from Arabs in Israel. Geogr. Rev. 2022, 112, 286–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, P.; Nandi, A.; Parutis, V.; Platt, L. Design and implementation of a high-quality probability sample of immigrants and ethnic minorities: Lessons learnt. Demogr. Res. 2018, 38, 513–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, M.N.; Finch, B.K.; Klein, D.; Ma, S.; Do, D.P.; Beckett, M.K.; Lurie, N. Sample designs for measuring the health of small racial/ethnic subgroups. Stat. Med. 2008, 27, 4016–4029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhadi, E. Religiosity and Muslim women’s employment in the United States. Socius 2017, 3, 2378023117729969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mansour, Y. The five dimensions of Muslim religiosity. Results of an empirical study. Methods Data Anal. 2014, 8, 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, A.; Sharabi, M. Women’s centrality of life domains: The Israeli case. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2022, 37, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhadi, E. The Hijab and Muslim women’s employment in the United States. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 2019, 61, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snir, R.; Harpaz, I. Test-retest reliability of the relative work centrality measure. Psychol. Rep. 2005, 97, 559–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Secular | Traditional | Religious | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (means) | 33.6 | 36.5 | 34 |

| Working hours (means) | 35 | 33.9 | 30.5 a |

| Number of children (means) | 1.3 | 2.1 | 2.7 a |

| Family status (%) b | |||

| Single | 52.5 | 24.4 | 29.7 |

| Married | 47.5 | 75.6 | 70.3 |

| Education (%) b | |||

| Secondary school and less | 10 | 24.3 | 26.7 |

| Postsecondary education | 10.1 | 17.9 | 20.8 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 54.9 | 43.6 | 38.6 |

| Higher than bachelor’s degree | 25 | 14.1 | 13.9 |

| Gross monthly income (%) b, c | |||

| <4000 | 17.4 | 15.4 | 33.7 |

| 4000–6600 | 30 | 32 | 33.6 |

| 6601–9200 | 30.1 | 33.3 | 27.7 |

| >9200 | 22.5 | 19.2 | 5 |

| Organizational status b | |||

| Worker | 66.7 | 81.9 | 88.7 |

| Manager | 33.3 | 18.1 | 11.3 |

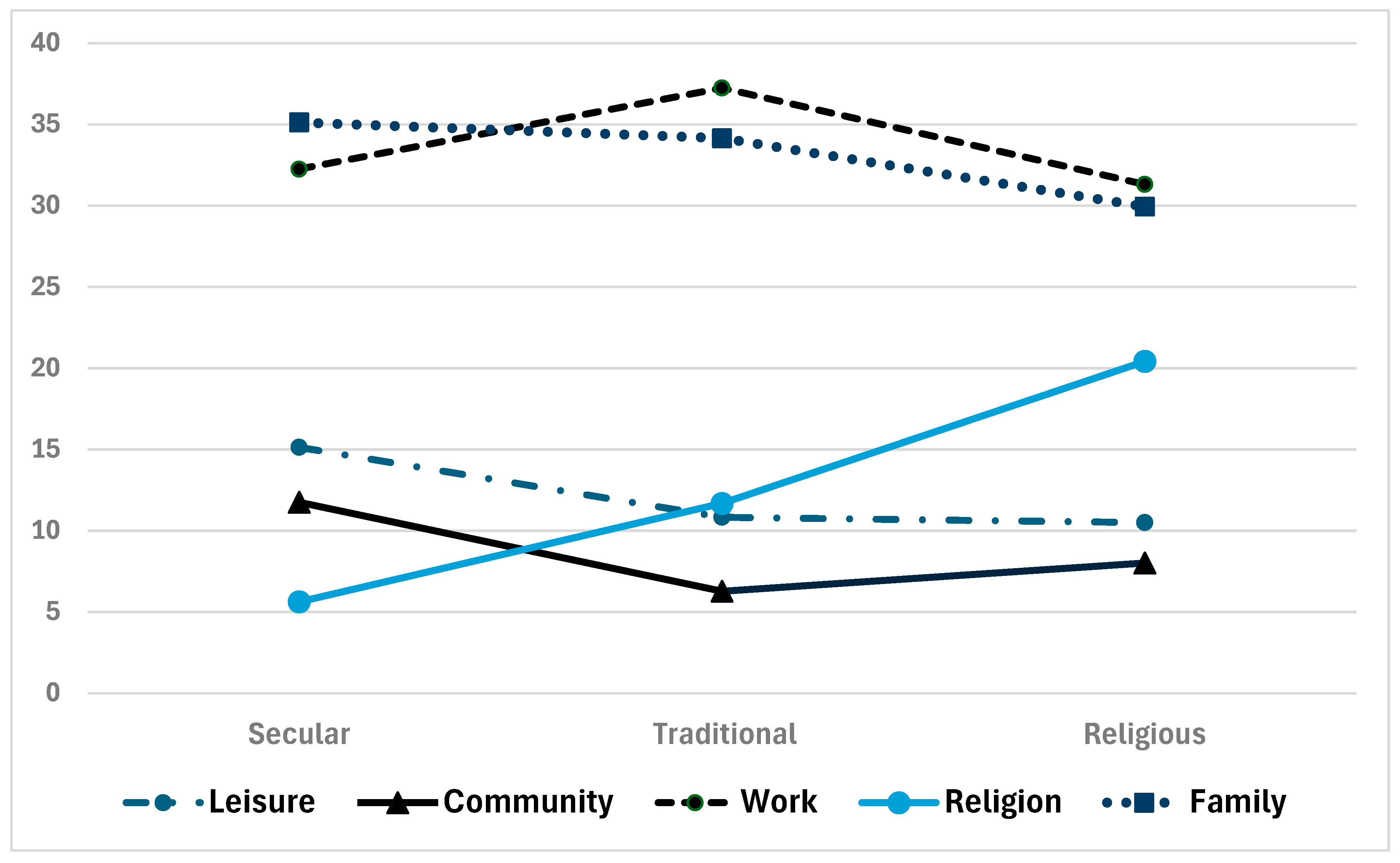

| Life Domain Centrality | Secular | Traditional | Religious | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | F | ||||

| Leisure | (3) | 15.13 bc | 10.77 | (4) | 10.83 b | 7.62 | (4) | 10.50 b | 9.65 | 3.91 * |

| Community | (4) | 11.75 bc | 8.29 | (5) | 6.28 | 7.09 | (5) | 8.02 b | 8.22 | 6.42 ** |

| Work | (2) | 32.25 b | 14.93 | (1) | 37.24 bc | 12.78 | (1) | 31.31 | 16.69 | 3.61 * |

| Religion | (5) | 5.63 c | 6.62 | (3) | 11.68 c | 7.70 | (3) | 20.42 bc | 11.32 | 41.32 ** |

| Family | (1) | 35.13 | 17.63 | (2) | 34.15 b | 14.60 | (2) | 29.94 bc | 16.64 | 2.21 + |

| Demographic Variables | Leisure | Community | Work | Religion | Family |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secular | |||||

| Age | 0.00 | −0.40 + | 0.31 | −0.34 | −0.01 |

| Family status a | −0.27 | −0.69 ** | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.44 + |

| Number of children | −0.18 | 0.57 + | −0.29 | 0.29 | 0.05 |

| Education level | −0.47 ** | 0.23 | 0.18 | −0.43 * | 0.21 |

| Working hours | −0.22 | 0.03 | 0.60 *** | −0.38 * | −0.23 |

| Occupational status b | 0.01 | −0.15 | 0.11 | −0.12 | 0.01 |

| Income | 0.31 | −0.03 | −0.22 | 0.34 | −0.12 |

| R2 | 0.36 | 0.31 | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.34 |

| F | 2.50 * | 2.01 + | 3.47 ** | 2.18 + | 2.30 * |

| Traditional | |||||

| Age | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.19 | −0.13 |

| Family status a | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.10 | −0.05 | 0.21 + |

| Number of children | −0.07 | −0.10 | −0.25 + | −0.12 | 0.32 * |

| Education level | −0.29 + | −0.15 | 0.12 | −0.31 * | 0.26 + |

| Working hours | −0.15 | −0.05 | 0.49 *** | −0.08 | −0.28 * |

| Occupational status b | 0.14 | −0.05 | −0.20 + | −0.24 + | 0.27 * |

| Income | −0.08 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.12 | −0.26 |

| R2 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.37 | 0.17 | 0.40 |

| F | 1.58 | 0.43 | 5.31 *** | 1.83 + | 5.34 *** |

| Religious | |||||

| Age | 0.05 | −0.10 | −0.07 | 0.11 | 0.01 |

| Family status a | −0.27 * | −0.28 * | 0.16 | −0.06 | 0.20 + |

| Number of children | −0.09 | 0.06 | −0.14 | 0.01 | 0.17 |

| Education level | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.13 | −0.22 + | 0.29 ** |

| Working hours | −0.16 | −0.13 | 0.53 *** | −0.25 + | −0.22 + |

| Occupational status b | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.14 | −0.10 | −0.07 |

| Income | 0.02 | 0.10 | −0.19 | 0.18 | −0.02 |

| R2 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.32 | 0.09 | 0.24 |

| F | 1.65 | 1.09 | 5.98 *** | 1.20 | 5.29 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharabi, M.; Shdema, I.; Manadreh, D.; Tannous-Haddad, L. Muslim Working Women: The Effect of Cultural Values and Degree of Religiosity on the Centrality of Work, Family, and Other Life Domains. World 2025, 6, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6020043

Sharabi M, Shdema I, Manadreh D, Tannous-Haddad L. Muslim Working Women: The Effect of Cultural Values and Degree of Religiosity on the Centrality of Work, Family, and Other Life Domains. World. 2025; 6(2):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6020043

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharabi, Moshe, Ilan Shdema, Doaa Manadreh, and Lubna Tannous-Haddad. 2025. "Muslim Working Women: The Effect of Cultural Values and Degree of Religiosity on the Centrality of Work, Family, and Other Life Domains" World 6, no. 2: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6020043

APA StyleSharabi, M., Shdema, I., Manadreh, D., & Tannous-Haddad, L. (2025). Muslim Working Women: The Effect of Cultural Values and Degree of Religiosity on the Centrality of Work, Family, and Other Life Domains. World, 6(2), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6020043