Current Challenges of Good Corporate Governance in NGOs: Case of Slovenia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Current State of Affairs for the Subject Matter of Our Study

3.2. Preliminary Insight into the State of Affairs in the Not-for-Profit Sector

- F1: Third Sector continues to grapple with significant challenges, primarily stemming from unresolved issues of the post-socialist transition.

- F2: Lack of self-awareness among owners: Ambivalence regarding ownership remains prevalent within the Third Sector, manifested in the fact that the founders of NGOs are both considered and not considered their actual owners. This means that the founders of NGO legal entities have limited sovereignty over them.

- F3: An entrenched view still exists that civil society, non-profit organizations, or the public sector as a whole are a subsystem of the economy, which is seen as an independent, self-sufficient subsystem of contemporary, developed society that only actively creates new added value; the main difference is that the first is considered “non-economic activity”, which is seen as detrimental to the economy and represents public spending and expenses that are fundamentally thought to impede economic growth.

- F4: A chronic disparity exists between the lofty programmatic goals, mission, and values of NGOs on the one hand and the actual results achieved in practice on the other. Consequently, this mismatch leads to a state of dysfunctional governance and/or managerial incongruence. The obvious shortcomings in non-profit organization management and leadership are among the main causes of this disparity.

- F5: There is still a persistent bias in Slovenia’s Third Sector that professional management will diminish the importance of NGOs and turn them into capitalist businesses.

- F6: Discrepancy between legal status regulation of NGOs and concrete conditions of their functioning in practice: they are obliged to operate in a market environment with non-professional staff, volunteers, enthusiasts, amateurs, etc., who are also underpaid for their work and often dissatisfied because of it.

- F7: Chronic resource deficiency: The absence of comprehensive and stable financing for NGOs based on their mission and programs, as opposed to the prevailing practice of financing individual projects, has resulted in a situation where an increasing number of NGOs competing for financial support are confronted with increasingly limited sources. Moreover, more and more funders refuse to cover the entire project costs, instead requiring NGOs to secure co-financiers as a precondition for partial financial support for a concrete project. Consequently, NGOs in Slovenia often have very limited resources, undoubtedly complicating the implementation of GCG. The lack of systematic funding, a consequence of exclusively funding individual projects that are appealing to sponsors or the government, rather than supporting the overall functioning of the entire NGO, opens a persistent gap in their budgets. This creates stress, trauma, and frustration for their management, as they grapple with how to ensure their survival in a market-driven economic environment. This situation bears a striking resemblance to the conditions that prevailed at the onset of the development of liberal capitalism in the 19th century: ruthless competition, selfishness, self-sufficiency, and animosity among NGOs, which, in principle and in their declared mission, should collaborate, complement each other, connect, and create social networks within the World of Life, as opposed to the World of the System.

- F8: Lack of expertise: NGOs in Slovenia exhibit a serious deficit of expertise in the field of GCG and management at all hierarchical levels. This is primarily due to their often-limited financial capabilities, preventing them from engaging and compensating educated personnel for undertaking such complex activities as GCG and their core operations. In the Third Sector, as of August 2023, according to data from the Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, there were approximately 12,000 employees compared to a total of over 931,200 active workers in the country according to SURS (2023) [93] representing a mere 0.0128%. As a result, NGOs are typically forced to (a) employ sub-educated personnel merely to fill sensitive positions and (b) consolidate multiple different functions or departments into a single individual, creating managers who look like “generals without an army.” In this way, middle managers become the sole workforce in their organizational units, while institute directors or society presidents become “know-it-alls” as they must act as lawyers, economists, psychologists, HR professionals, educators, marketers, lobbyists, advisors, fundraisers, public relations specialists, influencers, and more if necessary.

- F9: Lack of personnel in governing bodies and management: The dominant feature on the stage of the Third Sector is personnel understaffing and managerial illiteracy, coupled with the simultaneous belittling of the role and significance of GCG and management for the successful realization of an NGO’s mission in practice. Prejudices inherited from the past, when the communist party pejorative labeled so-called “techno-management” as a “deviation from the Party Line”, still persist. This deepens mistrust and aversion towards management as some kind of “foreign entity” in the realms of culture, healthcare, education, public services, and civil society. It has been perceived as a spirit of capitalism and commercialization, finding its rightful place in the world of business and finance.

- F10: Lack of an appropriate GCG culture. In the not-for-profit sector in Slovenia, there is still some resistance to the concept of GCG, perceiving it as a capitalist and bourgeois creation. This is compounded by a widespread misunderstanding of the essential need for the following: (a) Fundamental changes in the culture of NGOs, including educating their leaders in managerial skills and acquiring necessary competencies and expertise in this field. (b) A deeper understanding of the origins of the most significant current issues in this sector. (c) Reflection on potentially meaningful paths to address post-socialist transitional challenges within them.

- F11: Lack of autonomy: As seen above (Table 6), since the majority of civil society organizations are funded from the state budget, they become dependent on this sole source of income. Consequently, they lose autonomy from the current political option in power in Slovenia when determining their mission, setting the agenda for their projects, and behaving in practice. The glaring paradox is that non-governmental organizations in Slovenia are primarily financed by the Slovenian government, turning them into “governmental non-governmental organizations”, which is a contradictio in adiecto. Instead of establishing and maintaining a constant and critical distance from the political subsystem, civil society organizations in Slovenia have recently merged with it. As a result of such developments, the term “NGO” increasingly becomes something of an oxymoron.

- F12: Lack of ideological–political balance: The vast majority of NGOs not only espouse a leftist–anarchist worldview and engage in ideologies and practices reminiscent of regressive post-socialist doctrines but are also highly intolerant towards anything perceived as “right-wing”, “fascism”, “Janšism”, and similar labels. Indeed, the majority of NGOs continue to operate today following the model of so-called “socio-political organizations”, such as unions, the Socialist Alliance of the Working People, the Alliance of Socialist Youth, and so on, from the former regime, essentially serving as a transmission of the Communist Party of Slovenia as the sole party within the political subsystem during the era of self-management socialism.

- F13: The lack of resistance against cliques as a paradigm of corporate culture in the non-profit sector. Due to the prevalence of this phenomenon and insufficient attention to it in domestic academic circles, with one of the rare exceptions being our empirical study on cliques within a broader research on organizational culture, using the example of Pošta Slovenije d.d. [94], we had to rely on relevant global literature dealing with corporate culture in general (Deal and Kennedy [95]; Hofstede [96]; Schein [97]; Brown [98]; Cameron and Quinn [99]) as well as specifically on the phenomenon of cliques. By the way, a clique is an informal group of people within an organization who share common interests, goals, or values. Members of a clique often support and help each other progress within the organization. As a paradigm of corporate culture, a clique can have both positive and negative impacts on the organization. On the one hand, cliques can lead to increased productivity and innovation because members often share common ideas and goals. They can also contribute to greater cohesion and employee satisfaction, as members often feel a sense of belonging to the organization. On the other hand, cliques can lead to the following: (i) Spread of rumors and gossip, which can damage relationships among employees. (ii) Decreased productivity, as clique members may be more focused on their own interests than the organization’s. (iii) Discrimination and inequality in the organization, as clique members may favor each other over other employees. (iv) Bullying and mobbing, as clique members may harass or intimidate those who are not part of the clique. (v) Reduced productivity, as clique members may focus on their internal relationships rather than their work. Cliques can form based on various factors, including the following: (1) Job Type: Individuals performing the same or similar jobs may feel more connected and are inclined to form cliques. (2) Personal Characteristics: People with similar personal characteristics, such as age, gender, education, or interests, may be more likely to socialize and form cliques. (3) Position in the Organization: Individuals with the same or similar positions in the organization may feel that they share common interests and goals, making them more prone to forming cliques. (4) Shared Interests: Members of a clique may share common interests, such as sports teams, hobbies, or political ideologies. (5) Values: Clique members may share common values, such as respect, loyalty, or ambition. (6) Goals: Clique members may have common goals, such as career advancement or achieving specific business success. For example, we find that Ashforth and Mael’s seminal work on social identity theory provides a framework for understanding the formation and impact of cliques in organizations. They argue that individuals are motivated to join groups that provide them with a sense of identity and belonging. Cliques can fulfill such needs by creating a sense of shared purpose and values among their members [100]. Cialdini and Trost’s work on social influence highlights the role of conformity in group formation and behavior. They argue that individuals are more likely to conform to the norms of the groups they identify with. This can lead to the development of cliques with strong norms and a tendency to exclude outsiders [101]. Dill’s work on clique culture provides a detailed analysis of the characteristics and dynamics of cliques. He argues that cliques are often characterized by shared interests, strong bonds between members, and a sense of exclusivity. These factors can contribute to a clique’s power and influence within an organization [102]. Riordan and Shore’s research on organizational culture highlights the importance of a strong and positive corporate culture for organizational success. They argue that a culture that promotes open communication, collaboration, and respect can lead to increased employee engagement, productivity, and innovation. Cliques that foster negative or exclusionary behavior can undermine a company’s overall culture and hinder its progress [103]. “Shared values and goals, cohesion, participativeness, individuality, and the sense of ‘we-ness’ permeated clan-type firms. They seemed more like extended families than economic entities… typical characteristics of clan-type firms were teamwork, employee involvement programs, and corporate commitment to employees” [99] (p. 46). Finally, we would draw attention to more recent studies on the negative effects of cliques and negative relationships in team work [104], as well as to studies dealing with various problematic aspects of cliques in business life [105,106,107,108].

- F14: Lack of adequate focus. In the non-profit sector, there is a complete preoccupation of employees, volunteers, and incompetent leadership with the organization’s mission, while simultaneously ignoring the importance of GCG, which is, so to speak, in the “blind spot” of the key stakeholders. The consequences of such an attitude have not been absent, as they have plunged the entire sector into a serious endemic crisis with no apparent way out. There prevails a mindset that views the non-profit nature of the organization as automatically relieving its leadership and staff from any obligations to create new added value. Productivity is consistently devalued to push forward organizational climate phenomena such as job satisfaction, feel-good factors, socializing, partying, in a word, enjoyment. For complete happiness, all they need is to find an altruistic donor who would generously finance such a circus.

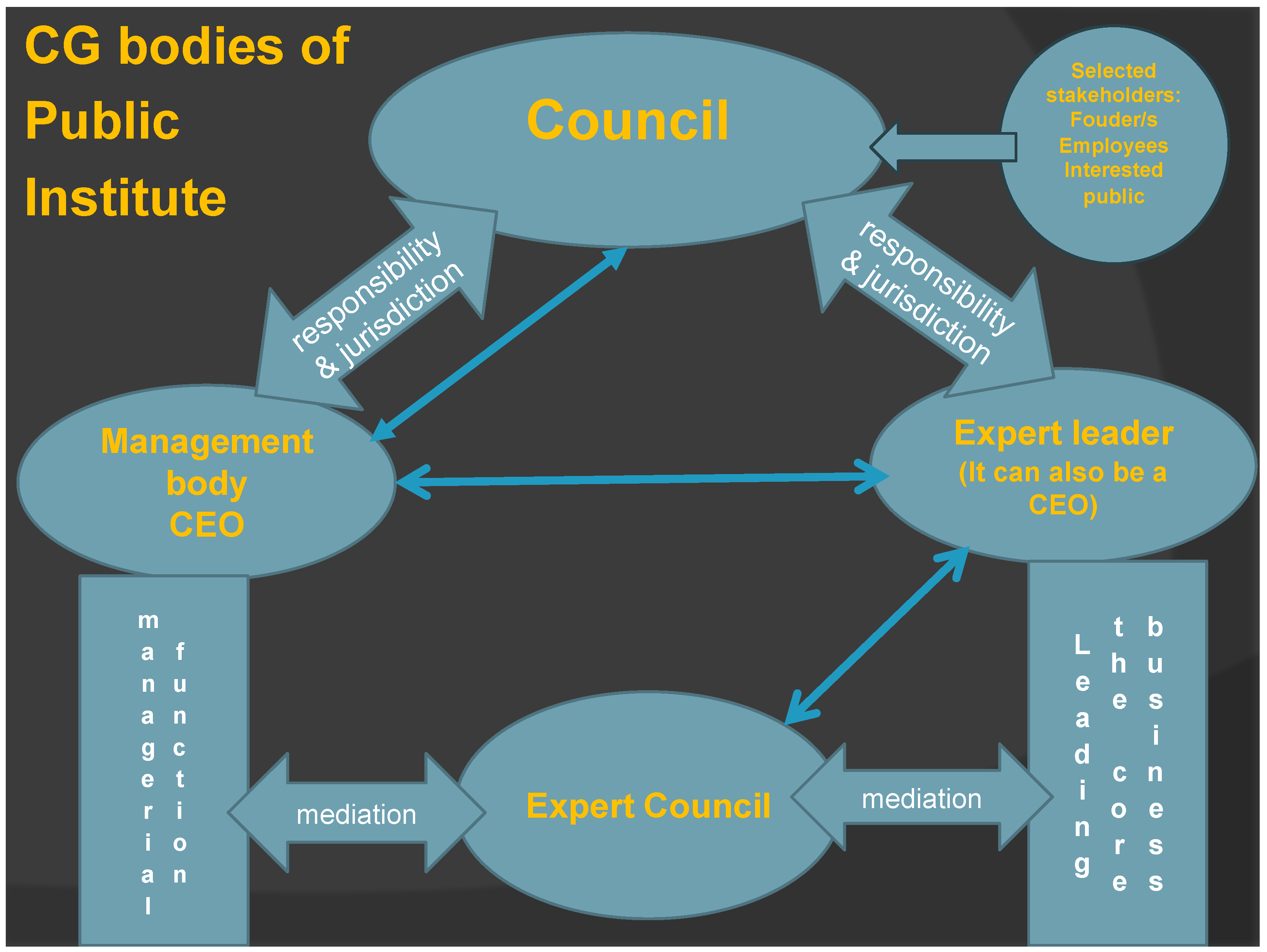

3.3. Legal–Organizational Framework of Corporate Governance in Public Institutes

- 1.

- The Council, as a collegiate governing body, consists of representatives of strictly selected stakeholders such as (1) founder/s, (2) representatives of the public institute’s employees, and (3) representatives of users and/or the interested public. The composition, method of appointment or election of members, term of office, and powers of the Council are determined by the law or act of establishment or by the statute or rules of the public institute (Article 29) [109]. The powers, jurisdiction, and responsibilities of the Council are as follows: (i) to adopt the statute or rules and other general/internal acts of the public institute, (ii) accept the institute’s work and development programs and monitor their implementation, (iii) determine the financial plan and accept the institution’s final account, (iv) propose to the founder a change or expansion of activity, and (v) give proposals and opinions to the founder and director of the public institute on individual issues, and perform other matters determined by law or the act of establishment or by the statute or rules of the public institute (Article 30) [109].

- 2.

- The CEO (Slovenian: direktor) as an individual management body (i) organizes and manages the work and operations of the institution, (ii) represents the public institute, (iii) is responsible for the legality of the institution’s work, (iv) manages the professional work of the public institute and is responsible for the professionalism of the institute’s work (unless the law or act of establishment, depending on the nature of the activity and the scope of work of the management function, stipulates that the management function and the function of managing the professional work of the public institute are separate) (Article 31) [109].The CEO is appointed and dismissed by the founder, if the public institute’s Council is not authorized to do so by law or the founding act. When the Council of the public institute is authorized to appoint and dismiss the CEO of a public institution, the founder gives his consent to the appointment and dismissal, unless otherwise provided by law. If the management function and the function of leading the professional work of the core business are not separated, the CEO is appointed and dismissed by the Council of the public institute with the consent of the founder (Article 32) [109].

- 3.

- The Expert Council as a collegiate professional body (i) deals with issues in the field of the professional work of the public institute, (ii) decides on professional issues within the framework of the jurisdiction specified in the statute or rules of the public institute, (iii) determines the professional basis for the institute’s work and development programs, (iv) gives opinions and proposals to the Council, the CEO, and the Expert Leader regarding the organization of work and conditions for the development of activities and performs other tasks specified by law or the act of establishment or by the public institute’s statute or rules. Its composition, method of formation and tasks are determined by the public institute’s statute or rules in accordance with the law and act of establishment (Articles 43–44) [109].

- 4.

- The Expert Leader (i) manages the institute’s professional work, if it is so determined by law or act of establishment, (ii) his or her rights, duties, and responsibilities are determined by the statute or rules of the public institute in accordance with the law or act of establishment, (iii) he or she is appointed and dismissed by the Council of the public institute based on the prior opinion of the Expert Council of the public institute, unless otherwise stipulated by law or the founding act (Articles 40–42) [109].

4. Results

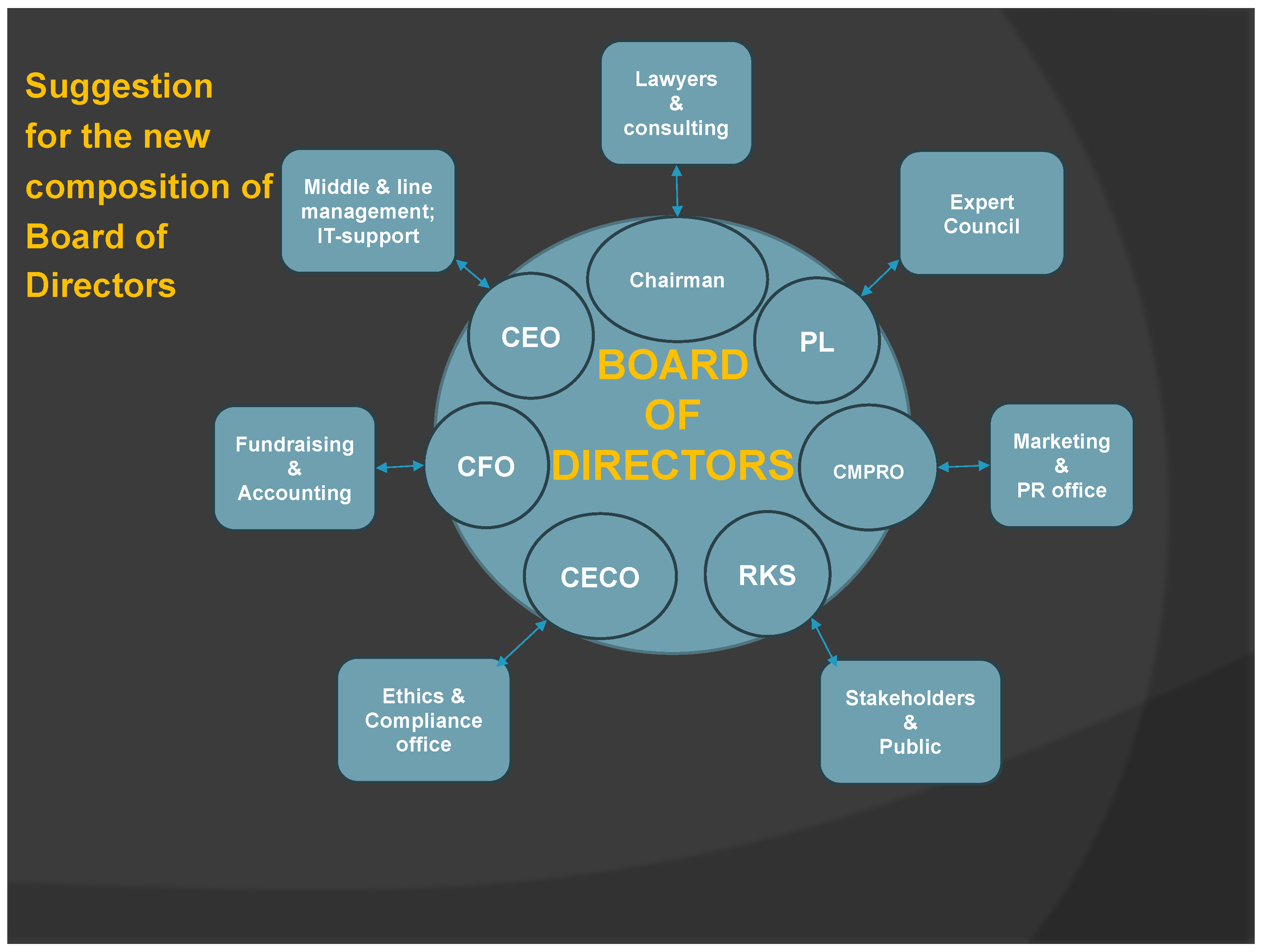

5. Discussion

- The Chairman of Board;

- CEO;

- Professional Leader;

- CFO;

- CMPRO (Chief Marketing and PR Officer);

- CECO (Chief Ethics and Compliance Officer); his/her duties & responsibilities should be to:

- creates and distributes business ethics policies, statements, and acknowledgments to support them;

- offers an internal evaluation of other NGO policies in order to guarantee corporate coherence and alignment with the ethical principles, incorporates the message of business ethics into the entire organisational culture;

- oversees the creation and execution of business ethics and conflict-of-interest policies. CECO also teaches senior management how to make ethical decisions and steer clear of conflicts of interest.

- investigates complaints and claims of unethical behaviour or conflicts of interest as soon as possible; writes investigative reports when required;

- every year, in collaboration with legal counsel of the Board of Directors, conducts corporate governance audits to assess the NGO’s condition and reports results to upper management and founder/s. The corporate goal of minimising the amount of employee data that must be kept by the NGO will be covered by corporate audits, together with risk minimization with regard to situations that encourage identity theft;

- creates and upholds private protocols for the processing and management of accusations and complaints. Establishes procedures for the private hearing of employee concerns about conflicts or ethics;

- keeps current on standards for corporate governance, compliance and reporting obligations, and relevant legal benchmarks from both state level and local communities.

- as allocated by Board of Directors, carries out further related tasks (summarised by: SHRM.org.) [112].

- RKS (representative of key stakeholders).

- (a)

- Promoting diversity and inclusion: This reduces the likelihood of cliques based on personal characteristics or position in the organization;

- (b)

- Promoting transparency, open communication, and collaboration among all employees and other key stakeholders of the public institute: This reduces the likelihood of conflict and discrimination between different cliques;

- (c)

- Setting clear expectations: This prevents or at least reduces the likelihood of corruption and other negative behaviors that may occur within cliques;

- (d)

- Emphasizing the importance of moral values and norms such as honesty, respect, equality, and justice: This reduces the influence of cliques on the institute’s corporate culture;

- (e)

- Appointing responsible individuals: Designate the CEO and CECO as individuals primarily responsible for resolving conflicts arising from cliques;

- (f)

- Training employees on the impact of cliques on corporate culture: NGOs should educate and train employees and volunteers on the dangers and negative aspects of cliques, how to recognize them, and how to reduce them to a manageable level.

- (1)

- Establish and foster an entrepreneurial spirit and transformational leadership according to Bass and Riggio [114]: This entails planning for the future as well as fostering an environment that rewards creativity and dynamic leadership in the face of pressing issues or challenges;

- (2)

- Transform the prevailing clan-type organizational culture in the corporate culture of the Adhocracy, which includes (a) management that “responds to urgent problems rather than planning to avoid them” [99]; (b) dealing with what is always ad hoc, implying something temporary, specialized, and dynamic [99] (p. 49); (c) recognizing that GCG in a hyper-turbulent world must resort to innovative and pioneering initiatives, developing new products and services to meet the future with an entrepreneurial spirit, creativity, and activity on the cutting edge [99]; and (d) a new cultural paradigm characterized by orienting the organization towards creativity, demanding that its leaders be innovators, entrepreneurs, and visionaries. The theory of efficiency, relying on innovation, vision, and new resources that bring transformation, innovative outputs, and agility, guides them in practice [99]. This is particularly challenging given that the metamorphosis of deeply rooted patterns of retrograde behavior in individuals and groups in the Third Sector to overcome the past and achieve current exemplary Western models of successful business will be a tough nut to crack for the board;

- (3)

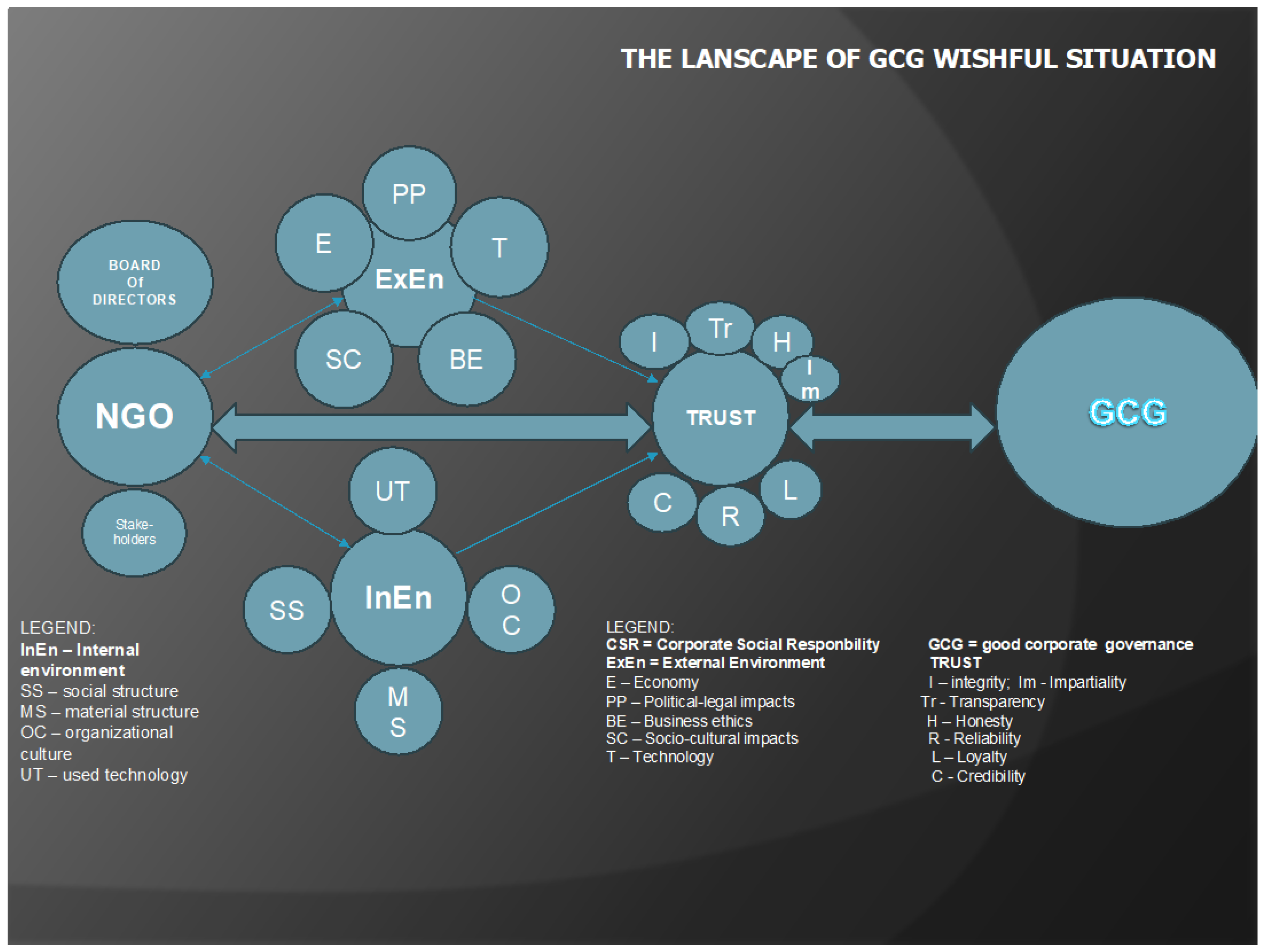

- Influence the reduction in established governance incongruence: The Board of Directors, through its activities, impacts a reduction in governance incongruence as it creates dissonance, which poses a serious hazard to successful corporate governance. To avoid dissonance between words and actions, decisions and outcomes, a relationship of highly correlated consistency must be established and maintained (see Figure 3 below);

- (4)

- To incorporate social entrepreneurship into the public institute’s operations to the greatest extent possible, because the principles of social economy align best with the not-for-profit nature of NGOs. The entrepreneurial spirit primarily aims to provide a market response to solving social, environmental, local, and other issues, thereby enabling the promotion of societal well-being. As is well known, social entrepreneurship is by definition a form of entrepreneurship that focuses on achieving social goals and community benefits. In contrast to traditional entrepreneurship, it places social goals, values, and missions ahead of economic goals. This aligns with the primary goal of all not-for-profit organizations, which is to shift the focus from profit to the following:

- (i)

- Addressing social problems and challenges (such as poverty, unemployment, social exclusion, environmental issues, health inequalities, and others);

- (ii)

- Improving the quality of life (especially for vulnerable communities and individuals, ensuring access to basic goods, services, and opportunities for all);

- (iii)

- Creating social value (by enhancing social capital, reinvesting profits back into the community, funding social programs, improving people’s quality of life);

- (iv)

- Social inclusion (particularly for vulnerable groups, including people with disabilities, the homeless, long-term unemployed, immigrants, and other marginalized groups);

- (v)

- Sustainable development (which includes environmental sustainability, social justice, and long-term economic stability, CSR, morality, and green initiative issues, etc.).

- A total of 92.17% of NGOs have no regularly employed staff, so the entire sector employs an average of 0.48% of those employed in NGOs; out of approximately 900,000 employed in Slovenia, only 12,500 have found employment in NGOs, representing a mere 0.14%;

- Regarding the annual income of NGOs, 89.38% generate less than EUR 50,000, while one-fifth (=19.25%) have no income at all. The total revenue of NGOs accounts for a modest 2.10% of the Slovenian GDP, while the EU average is twice as high. In such circumstances, the intention of professionals in the field of management and leadership to seek employment in NGOs cannot be expected, resulting in the sector being mainly managed by volunteers who are amateurs and enthusiasts;

- Most NGOs rely on state budgets and donations/sponsorships instead of independently earning financial resources for their existence and development, for example, in the form of social entrepreneurship, the green economy, circular economy, etc.;

- The Slovenian state allocates less than 1% of its budget to support the activities of NGOs (=0.97%), while the EU average is twice as high (=2.20%).

6. Theoretical and Practical Implications

- Use CSR not only as a promotional message but as a moral practice that builds trust among stakeholders and the broader public, serving as a necessary prerequisite for GCG;

- Ensure the Ethical Office effectively fulfills its role in the everyday life of the NGO consistently and tirelessly;

- Transfer the principles and norms of business ethics and green economy from “soft” factors to “hard” factors in their business policies;

- Recognize the importance of GCG in the constellation of business morals and consistently integrate it into their practices;

- Establish clear goals and values for their organization [117,118,119]. Based on empirical research on the organizational values used in practice by managers in the public and private sectors in Slovenia, researches found, in a representative sample of 400 respondents, that “efficiency” ranked 17th in importance in the public sector and even last (20th place) in the private sector [117]. This result was replicated in a study of Slovenian entrepreneurs, where efficiency also turned out to be of least importance [118]. For comparison, using the same research instrument, Van der Wal and Huberts found that efficiency ranked a high 7th among managers in the private sector in the Netherlands [119]. The authors of the Slovenian study attributed such results to historical and cultural factors in Slovenia, where it is evident that Weber’s Protestant ethic did not take deep roots, and memories of the half-century rule of self-managed socialism still influence the mindset and practical behavior patterns of managers [117];

- Effectively manage their resources;

- Use the grants from EU funds for structural policies to develop GCG;

- Collaborate with all key stakeholders;

- Better respond to the needs of their users and society as a whole;

- Process and disclose complete and timely information about their activities and finances transparently and responsibly.

Limitations

- (i)

- The absence of empirical research that would test the proposed conceptual model and thus verify its validity; we expect that such research will be conducted in the near future;

- (ii)

- Taking a single country (SLO) as a paradigmatic example for studying the phenomenon of GCG within NGOs, which here are still deeply embedded in a non-Western context due to their ongoing post-socialist transition;

- (iii)

- In the pursuit of truth through the maximization of value neutrality and objectivity, an occasional lack of political–ideological correctness;

- (iv)

- The use of anecdotal evidence, the authors’ extensive managerial experience accumulated over five decades in academia and in leading nonprofit organizations, and self-citations in cases where there is a lack of directly relevant literature by other authors on the specific aspect of GCG that lies at the core of our research interest;

- (v)

- Certain parts of the above text may seem to the reader prima facie as digressions from the main thread of the present article, but in fact they are a necessary explanation of the broader horizon within which our main subject of research is located;

- (vi)

- Definitions of well-known concepts within the academic community are omitted due to concerns about the scope of the article;

- (vii)

- Despite our maximum effort to maintain an academic, neutral writing style, in some places we had to make an exception and resort to stronger expressions that may be closer to slang because they better correspond to an authentic description of situations on the scene of the Third Sector, in which sometimes anomalies or insults to common sense occur;

- (viii)

- Because we have no prejudice against so-called older references, which is evident in the text, we did not divide references into fresh, say, not older than five years, and outdated, but into relevant vs. irrelevant, high-quality vs. weak, regardless of the year of publication, which may seem controversial to some academic people.

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CSR | Corporate social responsibility |

| NGO | Non-governmental organization |

| GCG | Good corporate governance |

| CEO | Chief Executive Officer |

| CFO | Chief Financial Officer |

| CMPRO | Chief Marketing and PR Officer |

| CECO | Chief Ethics and Compliance Officer |

| RKS | Representative of key stakeholders |

References

- Financial Reporting Council. Corporate Governance (Overview). 2023. Available online: https://www.frc.org.uk/library/standards-codes-policy/corporate-governance/corporate-governance-overview/ (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Corporate Governance. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/corporate-governance.html (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Directors’ Institute. Future of Corporate Governance: 10 Key Defining Trends. Available online: https://www.directors-institute.com/post/future-of-corporate-governance-10-key-defining-trends (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Diligent Corporation. Top Corporate Governance Trends for 2025 & Beyond. Available online: https://www.diligent.com/resources/blog/corporate-governance-trends (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Iskander, M.; Chamlou, N. Corporate Governance: A Framework for Implementation; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Young, S.; Thyil, V. A holistic model of corporate governance: A new research framework. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2008, 8, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyanto, Y.E.; Toolsema, L.A. Corporate Social Responsibility in a Corporate Governance Framework. 2007. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=987962 (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Crane, A.; McWilliams, A.; Matten, D.; Moon, J.; Siegel, D. The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ntim, C.G.; Soobaroyen, T. Corporate governance and performance in socially responsible corporations: New empirical insights from a Neo-Institutional framework. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2013, 21, 468–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, Y.; Ye, C. Corporate social responsibility disclosure and corporate governance: Empirical insights on neo-institutional framework from China. Int. J. Discl. Gov. 2018, 15, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, A. Corporate governance as social responsibility: A research agenda. Berkeley J. Int. Law 2008, 26, 452. [Google Scholar]

- Jamali, D.; Safieddine, A.M.; Rabbath, M. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility synergies and interrelationships. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2008, 16, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluge, N.; Schömann, I. Corporate governance, workers’ participation and CSR: The way to a good company. Transf. Eur. Rev. Labour Res. 2008, 14, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, D.L.; Szejnwald Brown, H.; De Jong, M. The contested politics of corporate governance: The case of the global reporting initiative. Bus. Soc. 2010, 49, 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobby Banerjee, S. A critical perspective on corporate social responsibility: Towards a global governance framework. Crit. Perspect. Int. Bus. 2014, 10, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, M.M.; Alam, S. Convergence of corporate social responsibility and corporate governance in weak economies: The case of Bangladesh. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 121, 607–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, R.D.; Ott, H.K. Corporate Social Responsibility and the Nonprofit Sector: Assessing the Thoughts and Practices Across Three Nonprofit Subsectors. Public Relat. J. 2014, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Crifo, P.; Rebérioux, A. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility: A typology of countries. J. Gov. Regul. 2016, 5, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aras, G.; Crowther, D. A Handbook of Corporate Governance and Social Responsibility; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, I.S.; Hitaj, C.; Benetto, E. Measuring the sustainability of investment funds: A critical review of methods and frameworks in sustainable finance. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 128016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentinov, V. Corporate social responsibility and the non-profit sector: Exploring the common ground. Kybernetes 2021, 50, 2651–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shava, E.; Thakhathi, D.R. Non-governmental organizations and the implementation of good governance principles. J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 47, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D. Non-governmental organizations, definitions, and history. In International Encyclopedia of Civil Society; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ngwira, V. Navigating the Corporate Governance Maze for Small Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs): A Narrative Review. Inverge J. Soc. Sci. 2023, 2, 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamad, S.; Fadzlyn, N.; Bawazir, A.A.; Hassan, N.H. The Role of Corporate Governance in Sustainability of Malaysian NGOs Operated Elderly Care Centres. Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 2024, 14, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenzhetayeva, A.; Aliyeva, A. Improving the effectiveness of non-governmental organizations. Sci. Collect. InterConf+ 2022, 25, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metin, H.; Coskun, A.; Kuzey, C. Factors affecting the effectiveness and sustainability of non-governmental organizations. Organ. Cult. 2021, 21, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S. The program efficiency of environmental and social non-governmental organizations: A comparative study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0302835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceesay, L.B. Exploring the Influence of NGOs in Corporate Sustainability Adoption: Institutional-Legitimacy Perspective. Jindal J. Bus. Res. 2020, 9, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandberg, Coro. 2018 Corporate Governance Best Practices Report. Coro Strandberg. Available online: https://corostrandberg.com (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Paužuolienė, J.; Šimanskienė, L.; Fiore, M. To Win or Not to Win: Analysis of Best Practices in Non-Governmental Organisations. In Non-Profit Organisations; Thrassou, A., Vrontis, D., Efthymiou, L., Weber, Y., Shams, S.M.R., Tsoukatos, E., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2024; Volume III, pp. 25–52. [Google Scholar]

- Naser, L. Good Governance Roles in Organizational Effectiveness of NGOs, A Balance Scorecard Approach—Evidence from Palestine. ResearchGate. 2019. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336902465_Good_Governance_Roles_in_Organizational_Effectiveness_of_NGOs_A_Balance_Scorecard_Approach-_Evidence_form_Palestine (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Aboramadan, M. NGOs management: A roadmap to effective practices. J. Glob. Responsib. 2018, 9, 372–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, Y. Stakeholders expectations for CSR-related corporate governance disclosure: Evidence from a developing country. Asian Rev. Account. 2021, 29, 97–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zietlow, J.; Hankin, J.A.; Seidner, A.; O’Brien, T. Financial Management for Nonprofit Organizations: Policies and Practices; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hermanto, Y.B.; Lusy, L.; Widyastuti, M. How Financial Performance and State-Owned Enterprise (SOE) Values Are Affected by Good Corporate Governance and Intellectual Capital Perspectives. Economies 2021, 9, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Mirchandani, A. Corporate governance and performance of microfinance institutions: Recent global evidences. J. Manag. Gov. 2020, 24, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, M. Partnerships and the Good-Governance Agenda: Improving Service Delivery Through State–NGO Collaborations. Voluntas 2019, 30, 1270–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Puyvelde, S. Nonprofit organization governance: A theoretical review. Volunt. Rev. 2016, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Young, D.R. Towards a unified theory of nonprofit governance. In Research Handbook on Nonprofit Governance; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham Glos, UK, 2021; pp. 409–423. [Google Scholar]

- Dicke, L.A.; Ott, J.S. (Eds.) Understanding Nonprofit Organizations: Governance, Leadership, and Management; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Renz, D.O.; Brown, W.A.; Andersson, F.O. (Eds.) The Jossey-Bass Handbook of Nonprofit Leadership and Management; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Molk, P.; Daniel Sokol, D. The challenges of nonprofit governance. BCL Rev. 2021, 62, 1497. [Google Scholar]

- López-Arceiz, F.J.; Bellostas, A.J. Nonprofit governance and outside corruption: The role of accountability, stakeholder participation, and management systems. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2020, 31, 311–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renz, D.O.; Brown, W.A.; Andersson, F.O. The evolution of nonprofit governance research: Reflections, insights, and next steps. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2023, 52 (Suppl. 1), 241S–277S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blevins, D.P.; Ragozzino, R.; Eckardt, R. “Corporate governance” and performance in nonprofit organizations. Strateg. Organ. 2022, 20, 293–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelovac, D. Podjetniška Kultura in Etika [Entrepreneurial Culture and Ethics]; VSŠP: Portorož, Slovenia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- De George, R. Business Ethics, 6th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hill: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, C.; Lovell, A. Business Ethics and Values: Individual, Corporate and International Perspectives, 2nd ed.; Financial Times; Prentice Hall: Harlow, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, A.; Matten, D. Business Ethics: Managing Corporate Citizenship and Sustainability in the Age of Globalisation, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell, O.O.; Fraedrich, J.; Ferrell, L. Business Ethics: Ethical Decision Making and Cases, 7th ed.; Houghton Mifflin Co.: Boston, MA, USA; New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher, T. Ethics and HRD: A New Approach to Leading Responsible Organizations; Persues Publishing: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Belak, J. Corporate governance and the practice of business ethics in Slovenia. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 2013, 26, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelovac, D.; Ljubojević, Č.; Ljubojević, L. HPC in business: The impact of corporate digital responsibility on building digital trust and responsible corporate digital governance. Digit. Policy Regul. Gov. 2022, 24, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolourian, S.; Angus, A.; Alinaghian, L. The impact of corporate governance on corporate social responsibility at the board-level: A critical assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 291, 125752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, M.R.; Porter, M. Creating Shared Value; FSG: Boston, MA, USA, 2011; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J.; Rowlands, I.H. Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st century business. Altern. J. 1999, 25, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, W.; MacDonald, C. Getting to the bottom of “triple bottom line”. Bus. Ethics Q. 2004, 14, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loviscek, V. Triple bottom line toward a holistic framework for sustainability: A systematic review. Rev. De Adm. Contemp. 2020, 25, e200017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; Wicks, A.C.; Parmar, B.L.; De Colle, S. Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; Zyglidopoulos, S. Stakeholder Theory: Concepts and Strategies; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E.; Phillips, R.; Sisodia, R. Tensions in stakeholder theory. Bus. Soc. 2020, 59, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. The politics of stakeholder theory: Some future directions. In R. Edward Freeman’s Selected Works on Stakeholder Theory and Business Ethics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 119–132. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Corporate Social Responsibility: A New Definition, a New Agenda for Action (MEMO/11/730). 2011. Available online: http://europa.eu/rapid/pressReleasesAction.do?reference=MEMO/11/730&format=HTML&aged=0&language=EN&guiLanguage=en (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- Drucker, P. The Practice of Management; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Golob, U.; Bartlett, J.L. Communicating about corporate social responsibility: A comparative study of CSR reporting in Australia and Slovenia. Public Relat. Rev. 2007, 33, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahovnik, M. Corporate governance following the Slovenian transition: From success story to failed case. J. Balk. Near East. Stud. 2019, 21, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovač, B. Beseda urednika [Editor’s Note]. Neprofit. Manag. 1999, 1–2, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Jelovac, D. Odisejada krmarjev neprofitnega sektorja [Odyssey of Nonprofit Sector Navigators]. In Jadranje po Nemirnih Vodah Menedžmenta Nevladnih Organizacija [Sailing Through Turbulent Waters of Non-Governmental Organization Management]; Jelovac, D., Ed.; Radio Študent; Študentska Organizacija Univerze v Ljubljani & Visoka Šola za Menedžment v Kopru: Ljubljana, Slovenia; Koper, Slovenia, 2002; pp. 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Rus, V. Management v neprofitnih organizacijah [Management of Non-for-profit Organizations]. In Management; Možina, S., Ed.; Didakta: Radovljica, Slovenia, 1994; pp. 938–973. [Google Scholar]

- Kranjc Žnidaršič, A. Ekonomika in Upravljanje Neprofitne Organizacije [Economics and Management of Nonprofit Organizations]; Dej: Postojna, Slovenia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Trunk Širca, N.; Tavčar, M. Management Nepridobitnih Organizacij [Management of Non-for-Profit Organizations]; Visoka Šola za Management: Koper, Slovenia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jelovac, D. (Ed.) Jadranje po Nemirnih Vodah Menedžmenta Nevladnih Organizacija [Sailing Through Turbulent Waters of Non-Governmental Organization Management]; Radio Študent; Študentska Organizacija Univerze v Ljubljani & Visoka Šola za Menedžment v Kopru: Ljubljana, Slovenia; Koper, Slovenia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kolarič, Z. Različni znanstveno-teorijski pristopi k preučevanju neprofitnih organizacij [Various Scientific and Theoretical Approaches to the Study of Non-for-profit Organizations]. In Jadranje po Nemirnih Vodah Menedžmenta Nevladnih Organizacija [Sailing Through Turbulent Waters of Non-Governmental Organization Management]; Jelovac, D., Ed.; Radio Študent; Študentska Organizacija Univerze v Ljubljani & Visoka Šola za Menedžment v Kopru: Ljubljana, Slovenia; Koper, Slovenia, 2002; pp. 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hrvatin, N. Ekonomski vidiki managementa nevladinih organizacija [Economic aspects of management of non-governmental organizations]. In Jadranje po Nemirnih Vodah Menedžmenta Nevladnih Organizacija [Sailing Through Turbulent Waters of Non-Governmental Organization Management]; Jelovac, D., Ed.; Radio Študent; Študentska Organizacija Univerze v Ljubljani & Visoka Šola za Menedžment v Kopru: Ljubljana, Slovenia; Koper, Slovenia, 2002; pp. 71–92. [Google Scholar]

- Svetlik, I. Management človeških virov v neprofitnem sektorju [HRM in non-for-profit sector]. In Jadranje po Nemirnih Vodah Menedžmenta Nevladnih Organizacija [Sailing Through Turbulent Waters of Non-Governmental Organization Management]; Jelovac, D., Ed.; Radio Študent; Študentska Organizacija Univerze v Ljubljani & Visoka Šola za Menedžment v Kopru: Ljubljana, Slovenia; Koper, Slovenia, 2002; pp. 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Fink Hafner, D. Analiza politik—Akterji, modeli in načrtovanje politike skupnosti [Policy Analysis—Actors, Models and Community Policy Planning]. In Jadranje po Nemirnih Vodah Menedžmenta Nevladnih Organizacija [Sailing Through Turbulent Waters of Non-Governmental Organization Management]; Jelovac, D., Ed.; Radio Študent; Študentska Organizacija Univerze v Ljubljani & Visoka Šola za Menedžment v Kopru: Ljubljana, Slovenia; Koper, Slovenia, 2002; pp. 105–124. [Google Scholar]

- Hren, M. Odnos nevladnih organizacij do slovenske civilne družbe, javnih služb, države, Crkve, političnih strank in profitnih orgamizacij [The attitude of non-governmental organizations towards Slovenian civil society, public services, the state, the Church, political parties and profit organizations]. In Jadranje po Nemirnih Vodah Menedžmenta Nevladnih Organizacija [Sailing Through Turbulent Waters of Non-Governmental Organization Management]; Jelovac, D., Ed.; Radio Študent; Študentska Organizacija Univerze v Ljubljani & Visoka Šola za Menedžment v Kopru: Ljubljana, Slovenia; Koper, Slovenia, 2002; pp. 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Jelovac, D. Vpliv medsebojnega odnosa civilne družbe in političnega podsistemana na družbeno regulacijo socio-sistemov-v-tranziciji: Izziv managementa NVO [Impact of the Relationship between Civil Society and the Political Subsystem on Societal Regulation of Socio-Systems in Transition: A Challenge for NGO Management]. In Jadranje po Nemirnih Vodah Menedžmenta Nevladnih Organizacija [Sailing Through Turbulent Waters of Non-Governmental Organization Management]; Jelovac, D., Ed.; Radio Študent; Študentska Organizacija Univerze v Ljubljani & Visoka Šola za Menedžment v Kopru: Ljubljana, Slovenia; Koper, Slovenia, 2002; pp. 135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, D. NGOs, management and the process of change: New models or reinventing the wheel? In Jadranje po Nemirnih Vodah Menedžmenta Nevladnih Organizacija [Sailing Through Turbulent Waters of Non-Governmental Organization Management]; Jelovac, D., Ed.; Radio Študent; Študentska Organizacija Univerze v Ljubljani & Visoka Šola za Menedžment v Kopru: Ljubljana, Slovenia; Koper, Slovenia, 2002; pp. 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Raos, M. Učeča se organizacija [Learning organisation]. In Jadranje po Nemirnih Vodah Menedžmenta Nevladnih Organizacija [Sailing Through Turbulent Waters of Non-Governmental Organization Management]; Jelovac, D., Ed.; Radio Študent; Študentska Organizacija Univerze v Ljubljani & Visoka Šola za Menedžment v Kopru: Ljubljana, Slovenia; Koper, Slovenia, 2002; pp. 161–182. [Google Scholar]

- Trunk Širca, N. Vodenje nevladnih organizacij v visokem šolstvu [Leading non-governmental organisations in higher education]. In Jadranje po Nemirnih Vodah Menedžmenta Nevladnih Organizacija [Sailing Through Turbulent Waters of Non-Governmental Organization Management]; Jelovac, D., Ed.; Radio Študent; Študentska Organizacija Univerze v Ljubljani & Visoka Šola za Menedžment v Kopru: Ljubljana, Slovenia; Koper, Slovenia, 2002; pp. 183–198. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, M. Fundraising in higher education. Case study: University of Bristol, UK. In Jadranje po Nemirnih Vodah Menedžmenta Nevladnih Organizacija [Sailing Through Turbulent Waters of Non-Governmental Organization Management]; Jelovac, D., Ed.; Radio Študent; Študentska Organizacija Univerze v Ljubljani & Visoka Šola za Menedžment v Kopru: Ljubljana, Slovenia; Koper, Slovenia, 2002; pp. 277–294. [Google Scholar]

- Verčič, D. Odnosi z javnostmi v neprofitnih organizacijah [PR in NGOs]. In Jadranje po Nemirnih Vodah Menedžmenta Nevladnih Organizacija [Sailing Through Turbulent Waters of Non-Governmental Organization Management]; Jelovac, D., Ed.; Radio Študent; Študentska Organizacija Univerze v Ljubljani & Visoka Šola za Menedžment v Kopru: Ljubljana, Slovenia; Koper, Slovenia, 2002; pp. 199–212. [Google Scholar]

- Kovač, B. Lobiranje v neprofitnem sektorju [Lobbying in Non-for-profit Sector]. In Jadranje po Nemirnih Vodah Menedžmenta Nevladnih Organizacija [Sailing Through Turbulent Waters of Non-Governmental Organization Management]; Jelovac, D., Ed.; Radio Študent; Študentska Organizacija Univerze v Ljubljani & Visoka Šola za Menedžment v Kopru: Ljubljana, Slovenia; Koper, Slovenia, 2002; pp. 213–230. [Google Scholar]

- Svetličič, M. Pogajanja v neprofitnem sektorju [Negotiations in the non-profit sector]. In Jadranje po Nemirnih Vodah Menedžmenta Nevladnih Organizacija [Sailing Through Turbulent Waters of Non-Governmental Organization Management]; Jelovac, D., Ed.; Radio Študent; Študentska Organizacija Univerze v Ljubljani & Visoka Šola za Menedžment v Kopru: Ljubljana, Slovenia; Koper, Slovenia, 2002; pp. 231–248. [Google Scholar]

- Čandek, S. Tehnike iskanja in načrtovanja pridobivanja sredstev—Dotacij, donacij v neprofitnem sektorju [Techniques of finding and planning the acquisition of funds—Grants, donations in the non-profit sector]. In Jadranje po Nemirnih Vodah Menedžmenta Nevladnih Organizacija [Sailing Through Turbulent Waters of Non-Governmental Organization Management]; Jelovac, D., Ed.; Radio Študent; Študentska Organizacija Univerze v Ljubljani & Visoka Šola za Menedžment v Kopru: Ljubljana, Slovenia; Koper, Slovenia, 2002; pp. 249–264. [Google Scholar]

- Šporar, P. Oris aktualnega dogajanja na področju nevladinih organizacij v Sloveniji in trendi za prihodnost [Outline of current events in the field of non-governmental organizations in Slovenia and trends for the future]. In Jadranje po Nemirnih Vodah Menedžmenta Nevladnih Organizacija [Sailing Through Turbulent Waters of Non-Governmental Organization Management]; Jelovac, D., Ed.; Radio Študent; Študentska Organizacija Univerze v Ljubljani & Visoka Šola za Menedžment v Kopru: Ljubljana, Slovenia; Koper, Slovenia, 2002; pp. 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Horvat, A. Nekatere možnosti razvoja neprofitnega in nevladnega sektorja na primeru uvajanja evropske regionalne strukturne pollitike v Sloveniji [Some possibilities for the development of the non-profit and non-governmental sector on the example of the introduction of the European regional structural policy in Slovenia]. In Jadranje po Nemirnih Vodah Menedžmenta Nevladnih Organizacija [Sailing Through Turbulent Waters of Non-Governmental Organization Management]; Jelovac, D., Ed.; Radio Študent; Študentska Organizacija Univerze v Ljubljani & Visoka Šola za Menedžment v Kopru: Ljubljana, Slovenia; Koper, Slovenia, 2002; pp. 339–351. [Google Scholar]

- Črnak-Meglič, A.; Rakar, T. The role of the third sector in the Slovenian welfare system. Teor. Praksa 2009, 46, 237–254. [Google Scholar]

- Philanthropy in Central & Eastern Europe. 2022. Available online: https://ceeimpact.org/slovenia-philanthropy-and-csr-in-cee/ (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- CNVOS. 2023. Available online: https://www.cnvos.si/nvo-sektor-dejstva-stevilke/stevilo-nvo/ (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- SURS. 2023. Available online: https://www.stat.si/StatWeb/news/Index/ (accessed on 16 December 2023).

- Jelovac, D.; Orlić, R.; Suklan, J.; Sršen, C. Organisational culture measurement: An empirical study of local and regional similarities and differences in case of Post of Slovenia Ltd. Innov. Issues Approaches Soc. Sci. 2016, 9, 8–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deal, T.; Kennedy, A. Corporate Cultures—The Rites and Rituals of Corporate Life; Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Inc.: Reading, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Cultures and Organizations: Intercultural Cooperation and its Importance for Survival; Harper Collins Business: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Schein, E.H. Organisational Culture and Leadership; Jossey Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A. Organisational Culture; Financial Times; Pitman Publishing: Harlow, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, K.; Quinn, R. Diagnosing and Changing Organisational Culture: Based on the Competing Values Framework, 3rd ed.; Jossey-Bass A Wiley Imprint: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Trost, M.R. Social influence: Social norms, conformity, and compliance. In The Handbook of Social Psychology, 4th ed.; Gilbert, D.T., Fiske, S.T., Lindzey, G., Eds.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 151–192. [Google Scholar]

- Dill, D.D. Clique culture. In The Handbook of Social Problems; Esman, A.H., Glassner, M.J., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 359–372. [Google Scholar]

- Riordan, C.M.; Shore, L.M. The relationship between organizational culture and organizational effectiveness. J. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 82, 653–664. [Google Scholar]

- Peretz, R.A.; Luria, G.; Kalish, Y.; Zohar, D. Safety climate strength: The negative effects of cliques and negative relationships in teams. Saf. Sci. 2021, 138, 105224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milana, M.; Luigi, T. Exploring the contribution of NGOs to European education governance through social network analysis. J. Educ. Policy 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciurbea, F.-E.; Cavanna, M.; Cornelia, R.A.D.A. Predictors of Adolescent Involvement in Cliques and Gangs. Anthropol. Res. Stud. 2021, 1, 24–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, K.; Chen, B.; Yang, B.; Zou, S. Linkage between service delivery and administrative advocacy: Comparative evidence on cliques from a mental health network in the US and an elderly care network in China. J. Comp. Policy Anal. Res. Pract. 2019, 21, 535–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimei, Y.; Saffer, A.J. Standing out in a networked communication context: Toward a network contingency model of public attention. New Media Soc. 2021, 23, 2902–2925. [Google Scholar]

- Zakon o Zavodih [Act on the Public Institutes (1991)]. Available online: http://pisrs.si/Pis.web/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO10 (accessed on 16 December 2023).

- Inglehart, R.; Welzel, C. Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, R.; Welzel, C. The World Cultural Map—World Values Survey 7. 2023. Available online: http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/ (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- SHRM. org. 2023. Available online: https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/tools-and-samples/job-descriptions/pages/ethics-officer.aspx (accessed on 16 December 2023).

- Jouber, H. Is the effect of board diversity on CSR diverse? New insights from one-tier vs two-tier corporate board models. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2021, 21, 23–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.; Riggio, R. Transformational Leadership, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zaman, R.; Jainb, T.; Georges Samarac, G.; Jamalic, D. Corporate governance meets corporate social responsibility: Mapping the interface. Bus. Soc. 2022, 61, 690–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devinney, T.M.; Schwalbach, J.; Williams, C.A. Corporate social responsibility and corporate governance: Comparative perspectives. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2013, 21, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelovac, D.; Wal, Z.; Jelovac, A. Business and government ethics in the new and old EU: An empirical account of public-private value congruence in Slovenia and the Netherlands. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 103, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralj, A.; Jelovac, D.; Mate, V. Organizational values and moral virtues of entrepreneur: An empirical study of Slovenian entrepreneurs. Innov. Issues Approaches Soc. Sci. 2013, 6, 109–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Wal, Z.; Huberts, L. Value Solidity in Government and Business: Results of an Empirical Study on Public and Private Sector Organizational Values. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2008, 38, 264–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, D. My Own Life. Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary; Eugene, M.F., Ed.; Liberty Fund: Carmel, Indiana, 1987; pp. xxxi–xxxvii. [Google Scholar]

| Date | Total Number of NGOs * | Societies | Public or Private Institutes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 17 September 2012 | 25,065 | 22,490 | 2324 |

| 4 November 2022 | 27,550 | 23,459 | 3831 |

| 17 November 2023 | 27,407 | 23,236 | 3907 |

| 4 December 2023 | 27,399 | 23,237 | 3902 |

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Total employees in NGOs (2021) | 12,561 |

| NGOs without employees (%) | 92.17% |

| Societies without employees (%) | 95.48% |

| Public institutes without employees (%) | 70.11% |

| NGOs with at least one employee (%) | 7.83% |

| Societies with at least one employee (%) | 4.52% |

| Public institutes with at least one employee (%) | 29.89% |

| Institutions with at least one employee (%) | 6.33% |

| Public institutes’ share of total NGO employment (%) | >50% |

| Average employees per NGO | 0.48 |

| Average employees per public institute | 2.13 |

| Average employees per institution/society | 0.23 |

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Total NGO revenue (2021) | >EUR 1 billion |

| Societies’ contribution to total revenue (%) | 60.41% |

| NGOs with revenue < EUR 50,000 (%) | 89.38% |

| NGOs operating without income (%) | 19.25% |

| First recorded decline in NGO revenues | 2020 |

| Society revenue decrease (2011, 2013) | Yes |

| Society revenue growth after 2013 | Steady increase |

| Society revenue increase (2018) | 3.04% |

| Society revenue increase (2019) | 6.63% |

| Society revenue decline (2020) | 15.56% |

| Society revenue rebound (2021) | 18.89% |

| Public institutes’ only revenue decline | 2012 |

| Public institutes’ revenue recovery | 2013 |

| Institutional revenue decrease (2011, 2014) | Yes |

| Institutional revenue surpasses pre-crisis | 2015 |

| Institutional revenue drops below 2009 levels | 2016–2017 |

| Institutional revenue recovery above crisis levels | 2018–2019 |

| Institutional revenue decline (2020) | ~28% |

| Institutional revenue increase (2021) | 14.39% |

| Institutional revenue in 2021 vs 2019 levels | Below 2019 |

| Indicator | Value |

|---|---|

| NGO revenues as % of Slovenia’s GDP (2021) | 2.10% |

| Global average NGO revenues as % of GDP (2013) | 4.13% |

| EU average NGO revenues as % of GDP (2013) | 3.8% |

| Slovenia’s NGO sector characterization | Marginalized compared to other countries |

| Key indicators of NGO sector development | (1) Share of public revenues in total NGO revenues (2) Share of GDP allocated to NGOs |

| State’s role in NGO development | Indicates level of NGO integration into public services |

| Indicator | Value |

|---|---|

| Public funds as % of total NGO revenues (2017) | 35.57% |

| Public funds as % of total NGO revenues (2021) | 46.35% |

| Public funds as % of total NGO revenues (2010) | 40.01% |

| Key factor in 2021 increase | Increased funds from the Ministry of Labor, Family, Social Affairs, and Equal Opportunities (personal assistance services) |

| Share of GDP allocated to NGOs (Slovenia, 2021) | 0.97% |

| Global average share of GDP allocated to NGOs | 1.38% |

| EU average share of GDP allocated to NGOs | 2.20% |

| Indicator | Value |

|---|---|

| Public funds received by NGOs (2003) | EUR 166.76 million |

| Public funds received by NGOs (2021) | EUR 507.87 million |

| Funds from budget users (ministries, municipalities, FURS, public agencies, institutes) | EUR 482.54 million |

| Funds from FIHO and FŠO | EUR 25.33 million |

| Funds received by NGOs operating in the public interest (2021) | EUR 278.58 million |

| (57.73% of all budget user transfers) | |

| NGOs receiving public budget funds (2021) | 15,037 NGOs |

| (52.80% of all active NGOs) | |

| Funds received from ministries (2021) | EUR 245.49 million |

| Increase in ministry funding compared to 2003 | +522.02% (EUR 206.02 million more) |

| Increase in ministry funding compared to 2009 | +213.25% (EUR 167.12 million more) |

| Ministry providing the most funds to NGOs (2021), | |

| Ministry of Labor, Family, Social Affairs, and Equal Opportunities | (60.86% of all ministry funds) |

| Funds allocated for personal assistance | |

| (from the above ministry) | EUR 107.99 million |

| (72.29% of ministry’s NGO funds, 43.99% of all ministry-to-NGO transfers) | |

| Ministry of Education, Science, and Sport funding share | 19.96% |

| Ministry of Defense funding share | 6.08% |

| Funds received from municipalities (2021) | EUR 123.73 million |

| Increase in municipal funding compared to 2020 | +7.79% (EUR 8.94 million more) |

| Increase in municipal funding compared to 2003 | +97.68% (EUR 61.14 million more) |

| Increase in municipal funding compared to 2009 | +34.93% (EUR 32.03 million more) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jelovac, D. Current Challenges of Good Corporate Governance in NGOs: Case of Slovenia. World 2025, 6, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6010028

Jelovac D. Current Challenges of Good Corporate Governance in NGOs: Case of Slovenia. World. 2025; 6(1):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6010028

Chicago/Turabian StyleJelovac, Dejan. 2025. "Current Challenges of Good Corporate Governance in NGOs: Case of Slovenia" World 6, no. 1: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6010028

APA StyleJelovac, D. (2025). Current Challenges of Good Corporate Governance in NGOs: Case of Slovenia. World, 6(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6010028