Groundwater Quality and Potential Health Risk Assessment for Potable Use

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of Study Area

2.2. Geology and Aquifers

2.3. Site Selection

2.4. Sample Collection and Water Quality Analyses

2.5. Statistical and Mapping Analysis

2.6. Groundwater Quality Index (GWQI)

2.7. Heavy Metal Contamination Indices (HPI and HEI)

2.8. Irrigation Water Quality Parameters (Sodium Adsorption Ratio (SAR), and Sodium Percentage (% Na))

2.9. Health Risk Index

3. Results

3.1. Water Quality Parameters of Ramganga River Basin

3.1.1. Water Quality in Pre-Monsoon Season

3.1.2. Water Quality in Post-Monsoon Season

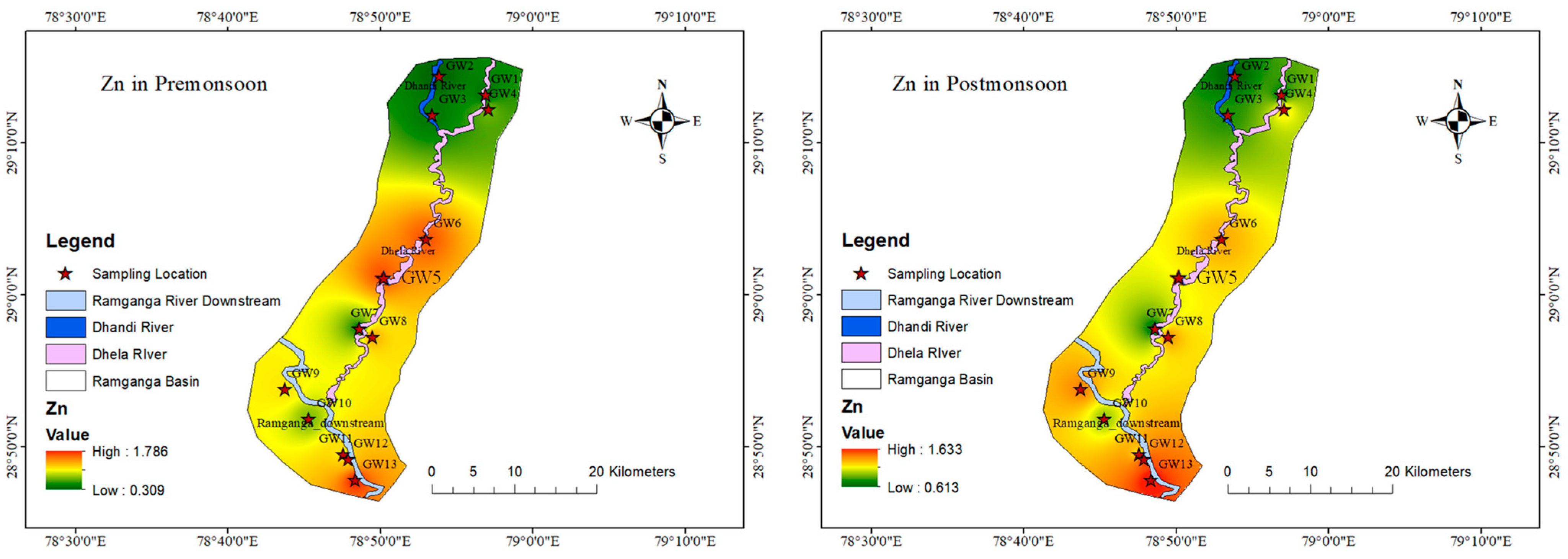

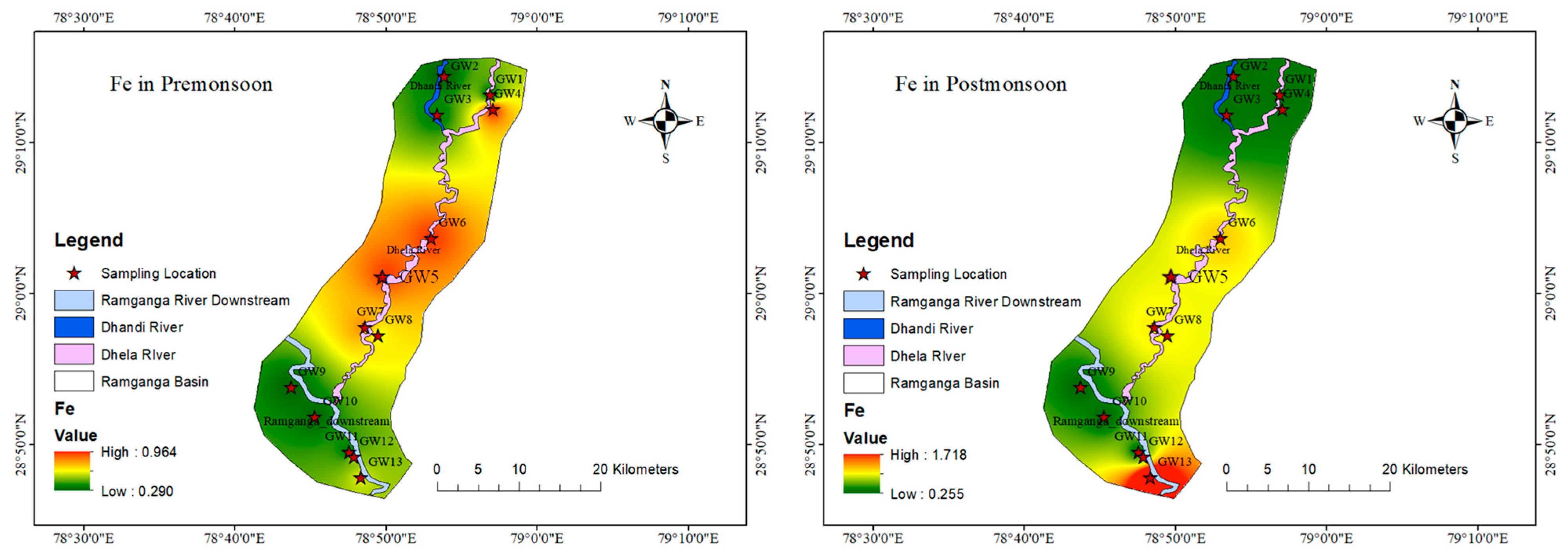

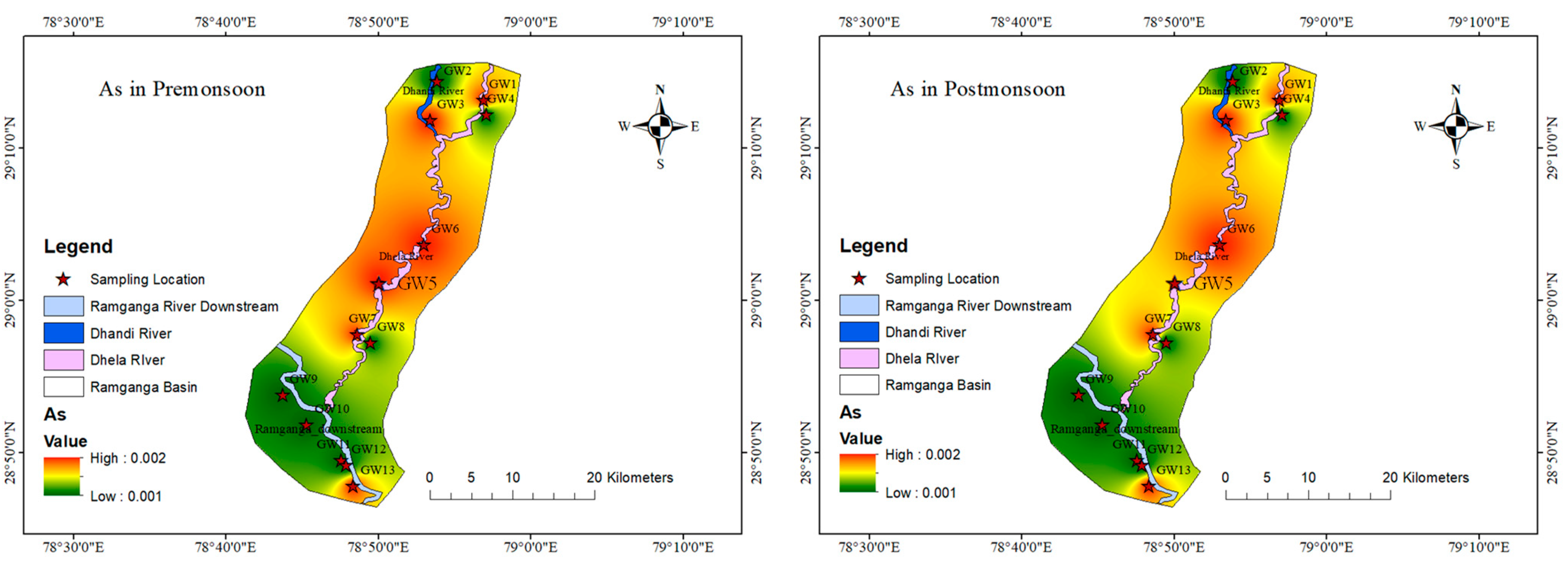

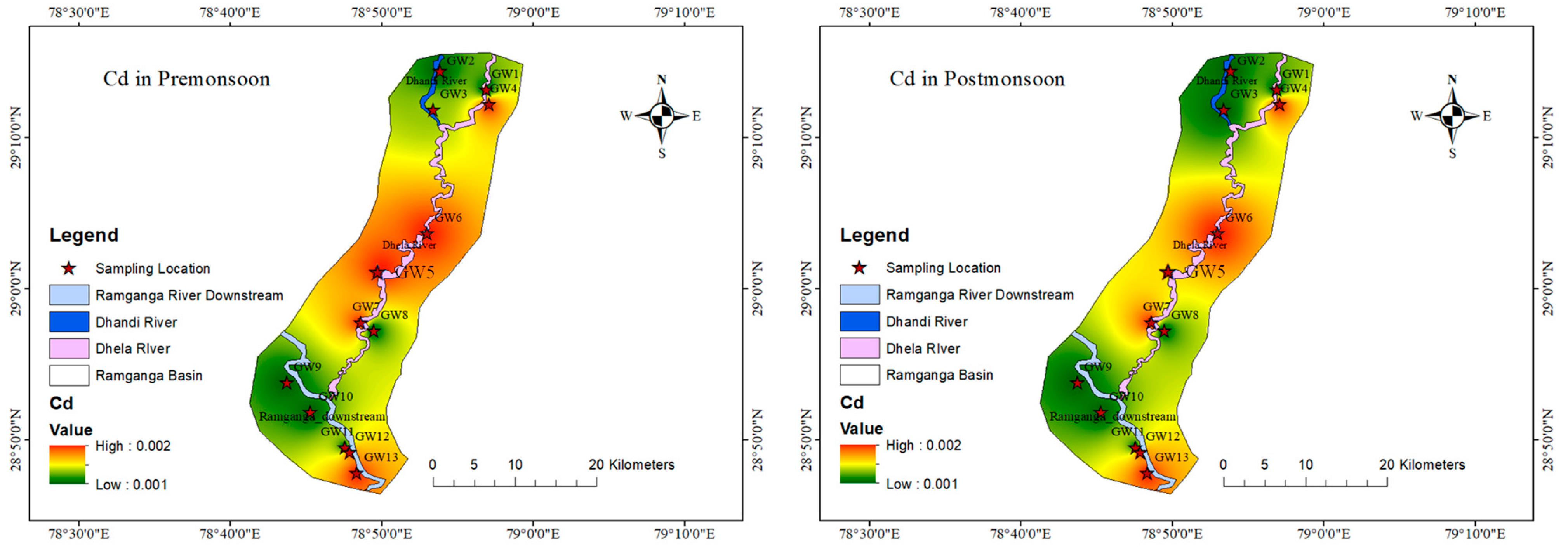

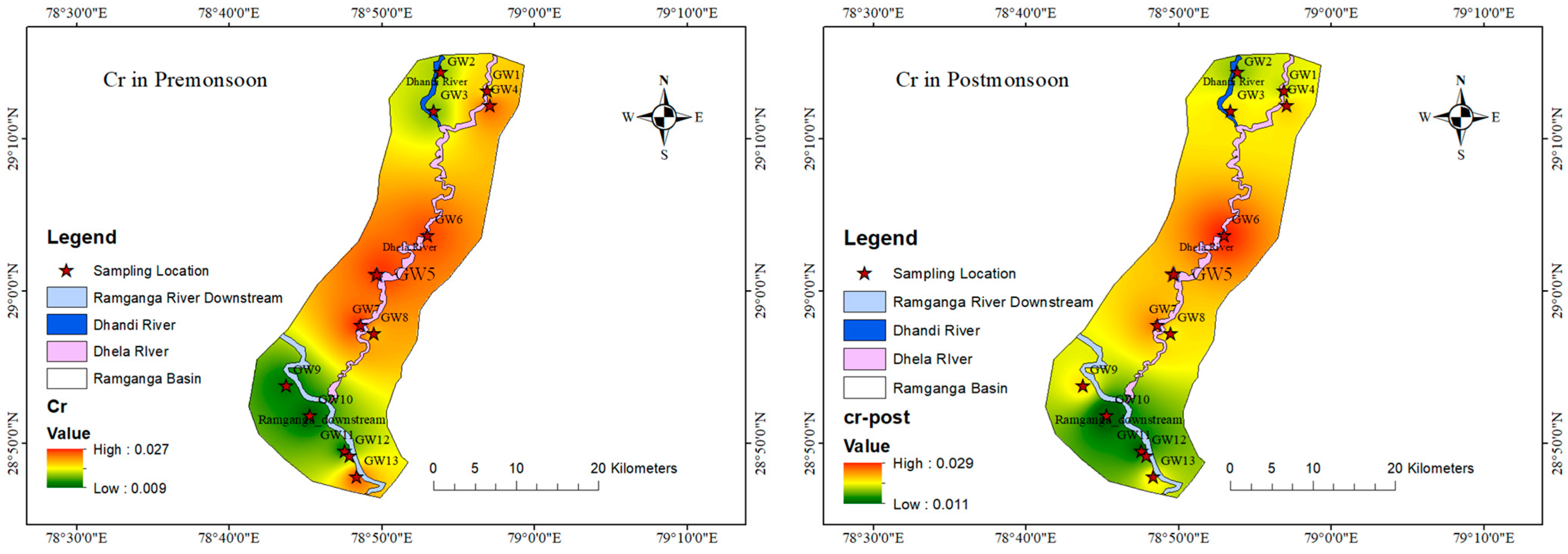

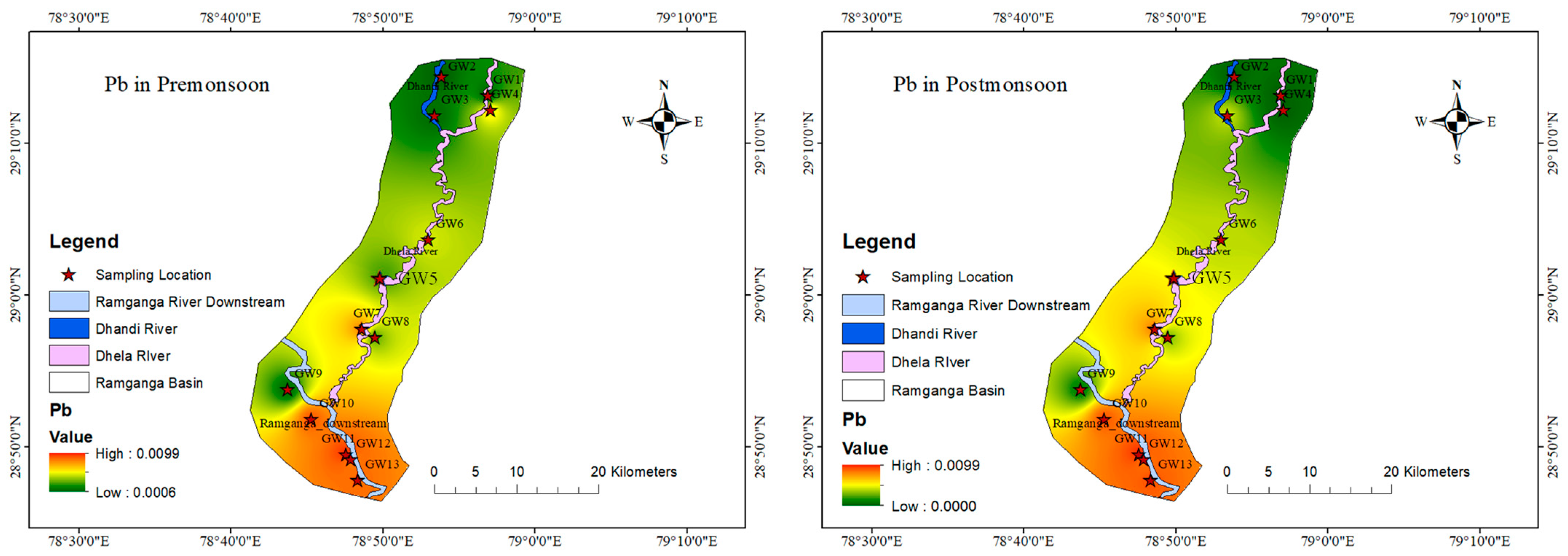

3.1.3. Spatial Map Distribution of Water Quality Parameters during Pre-Monsoon and Post-Monsoon

3.2. Groundwater Quality Index

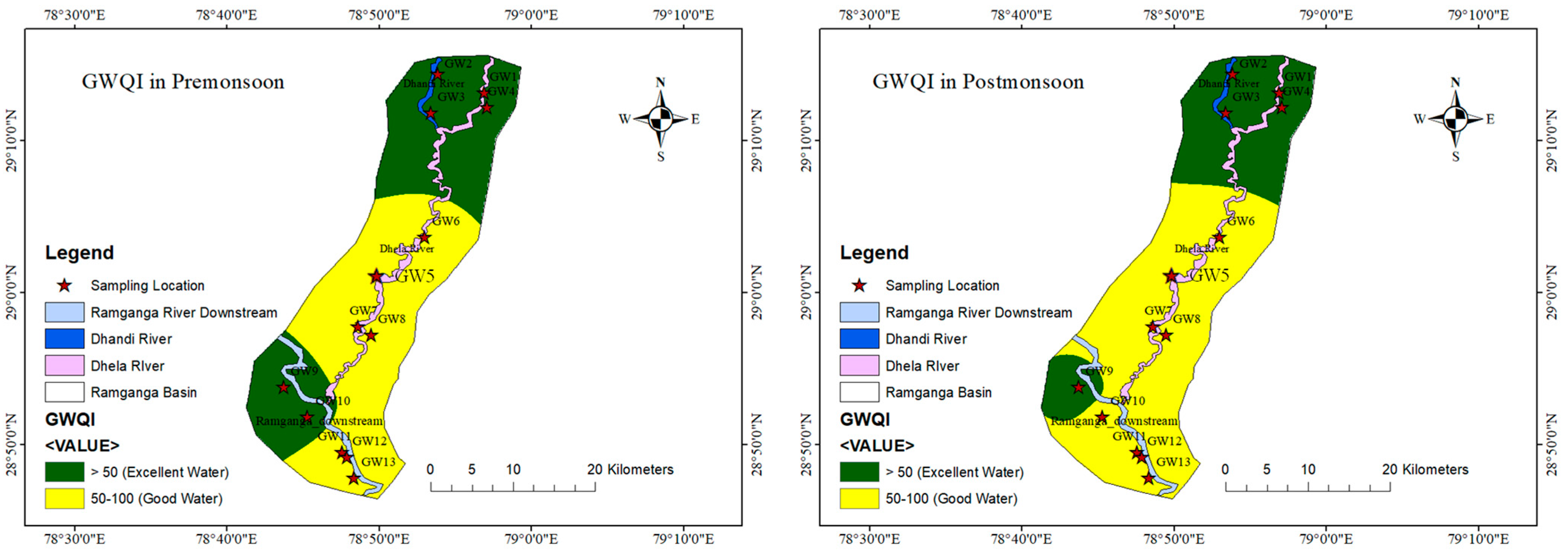

GWQI in Pre-Monsoon Season and Post-Monsoon Season

3.3. Heavy Metal Pollution Index (HPI) and Heavy Metal Evaluation Index (HEI)

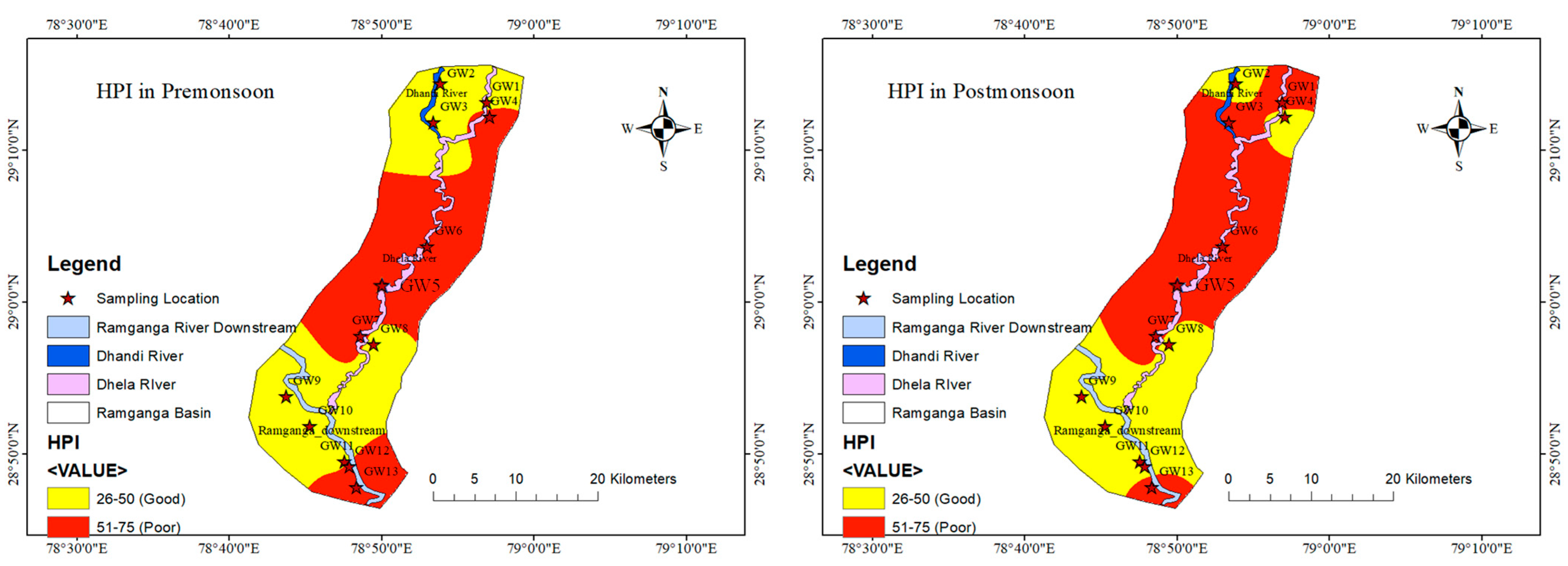

3.3.1. HPI in Pre-Monsoon and Post-Monsoon Seasons

3.3.2. Heavy Metal Evaluation Index (HEI) in Pre-Monsoon and Post-Monsoon Seasons

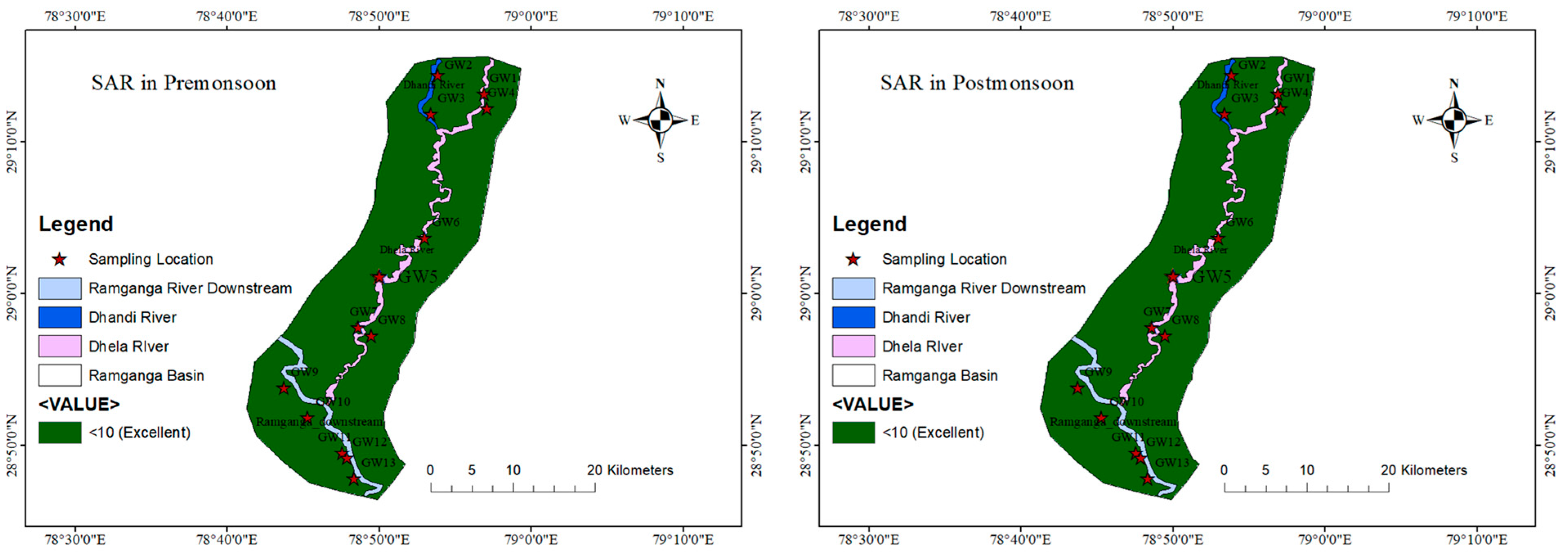

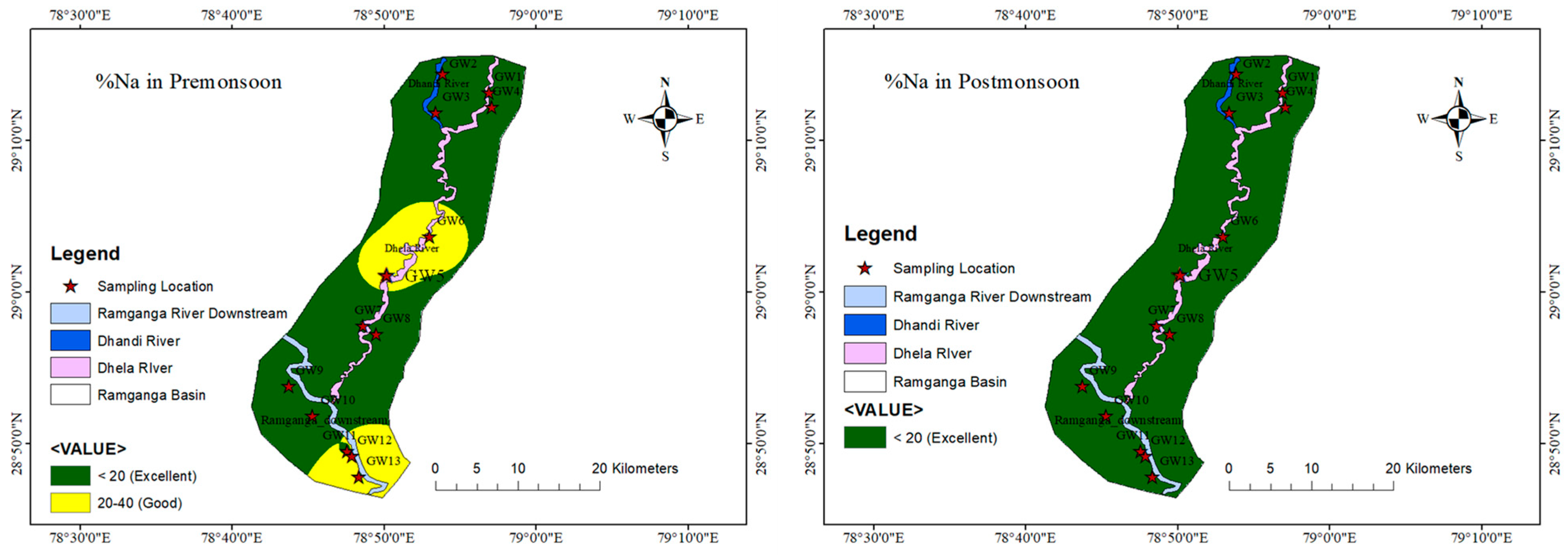

3.4. Result of Irrigation Water Quality Parameters (Sodium Adsorption Ratio (SAR) and Sodium Percentage (% Na))

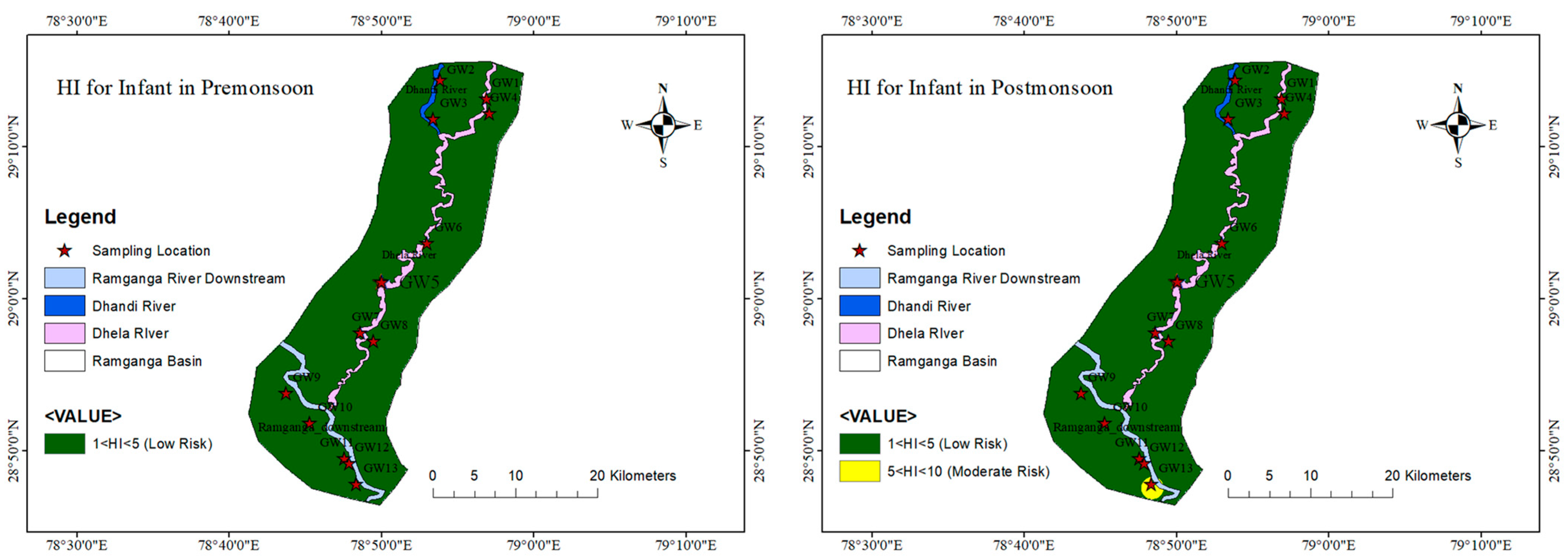

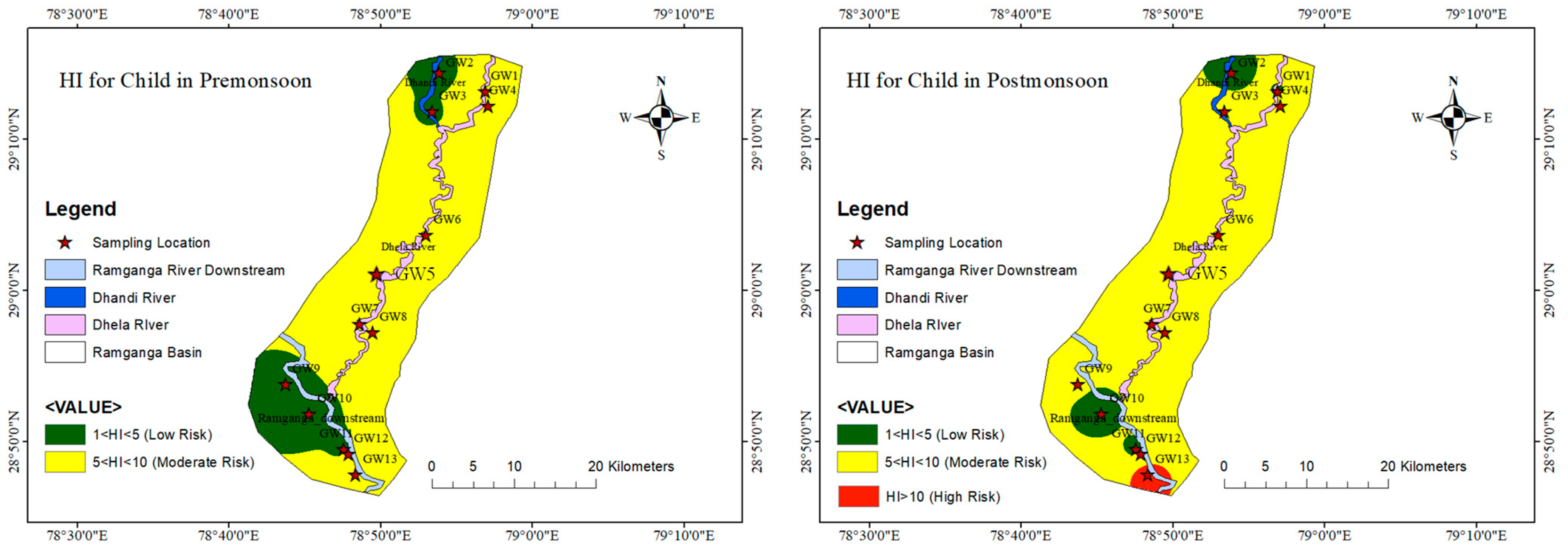

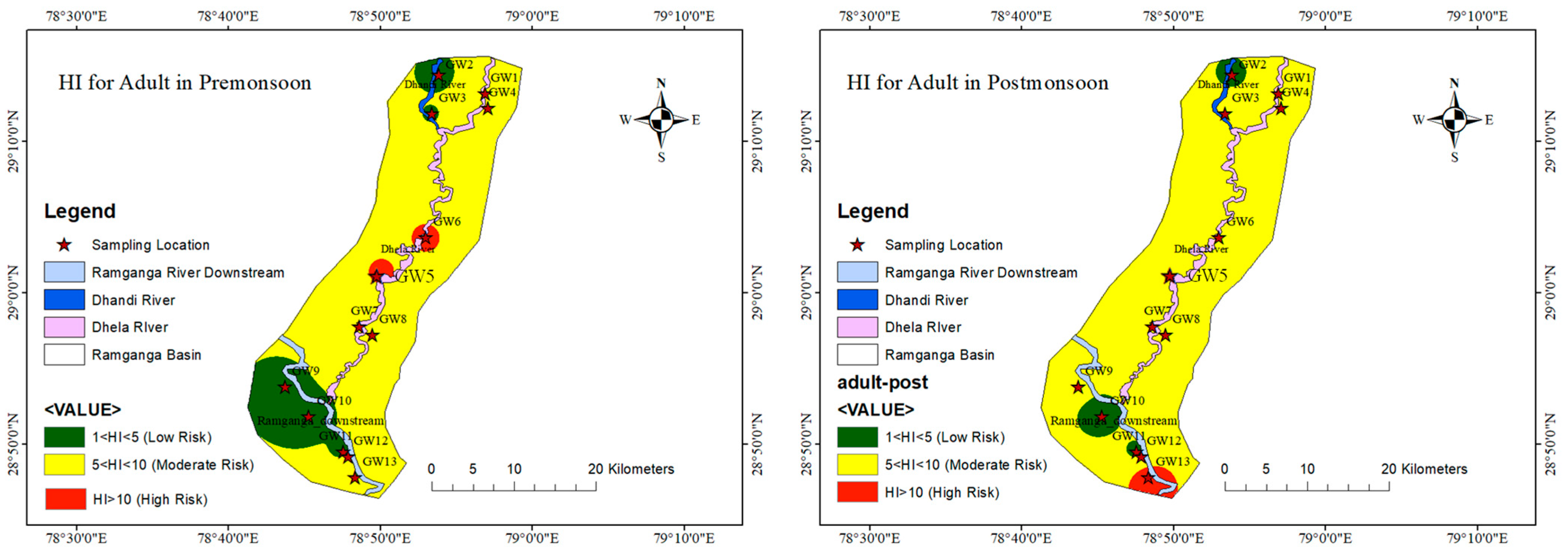

3.5. Health Risk Index for Local Inhabitants

Result of HI in Pre-Monsoon and Post-Monsoon Seasons

4. Conclusions

5. Recommendation

- Throughout the study, the GWQI values show excellent to good water quality, with slight changes noted between the pre- and post-monsoon seasons. Most exceptional water quality classifications highlight how groundwater is generally suitable for various uses, such as drinking and irrigation. To avoid any deterioration over time, attention should be made to areas with acceptable water quality.

- The results of the HPI and HEI show heavy metal and metalloids contamination in some of the sample sites, and the pollution levels are constant in both seasons. These results highlight the critical need for focused remediation initiatives and strict monitoring protocols to lessen the negative effects of heavy metal and metalloids contamination on the ecosystem and public health.

- Across the studied sites, the evaluation of SAR, % Na, and PI values shows excellent water quality suited for irrigation. However, to guarantee ideal soil permeability and guard against future soil degradation, attention should be given to areas with lower % Na levels.

- In agricultural-dominated areas, nitrate and phosphate concentrations are higher, as influenced by the use of fertilizers. These variables are useful signs of agricultural runoff; we should use them in tracking the effect that farming practices have on the water quality of an aquifer.

- Frequent concentrations of heavy metals like Lead (Pb), Cadmium (Cd), and Chromium(Cr) were noted in the industrial regions, and these may be attributed to untreated industrial effluence. These pollutants are very dangerous to human health, and we suggest that heavy metal analysis should be conducted in these regions, most especially in the periods of pre- and post-monsoon rains so that adequate treatment measures can be taken.

- Out of all the criteria, the main ones which are affected by urbanization consist of the imbalance of the Total Dissolved Solids (TDSs) and chlorides (Cl-), which are augmented by the output of urban waste. These values should be kept under check as a maximum, especially in areas where one’s main input is urban runoff.

- In the downstream area of the river, TDSs, chlorides, and some of the heavy metal concentrations, for example, zinc and lead, were observed to be higher, especially where industrial activities were involved. All these enrichments are likely to be due to the overall impacts of the sources of pollutants upstream. It is therefore imperative that these parameters be monitored downstream to determine the effects of industrial and urban development on the water quality.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar, A.; Patil, M.; Singh, A.N. Shivalik, Siwalik, Shiwalik or Sivalik: Which one is an appropriate term for the foothills of Himalaya? J. Sci. Res. 2020, 64, 640101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R.K.; Prasad, K. Management of water quality and biodiversity of the River Ganga. In Ecosystems and Integrated Water Resources Management in South Asia; Routledge India: New Delhi, India, 2020; pp. 104–132. [Google Scholar]

- Sur, H.S.; Bhardwaj, A.; Jindal, P.K. Performance evaluation and impact assessment of a small water-harvesting structure in the Shiwalik foothills of northern India. Am. J. Altern. Agric. 2001, 16, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potdar, K.; Namrata, N.; Sami, A. Nature, culture and humans: Patterns and effects of urbanization in lesser Himalayan Mountainous historic urban landscape of Chamba, India. J. Herit. Manag. 2017, 2, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medda, S.; Dey, S.R. Status of ichthyofaunal diversity of river ganga in Malda District of West Bengal, India. Int. J. Adv. Life Sci. Res. 2021, 4, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, A.; Kamboj, N.; Kamboj, V. Groundwater Quality and Potential Health Risk Assessment in the Vicinity of Solid Waste Dumping Sites of Quaternary Shallow Water Aquifers of Ganga Basin. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2022, 233, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Y.A.; Gani, K.M.; Chakrapani, G.J. Assessment of surface water quality and its spatial variation. A case study of Ramganga River, Ganga Basin, India. Arab. J. Geosci. 2016, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Kothari, A.; Kumar, A.; Rathi, H.; Goyal, B.; Gupta, P.; Singh, B.; Mirza, A.A.; Dhingra, G.K. Evaluation of physicochemical, heavy metal and metalloids pollution and microbiological indicators in water samples of Ganges at Uttarakhand India: An impact on public health. Int. J. Environ. Rehabil. Conserv. 2020, 11, 445–466. [Google Scholar]

- Kazuo, T. Industrialization and the development of regional economies in the State of Uttarakhand. J. Urban Reg. Stud. Contemp. India 2014, 1, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M.; Kookana, R.S.; Mehta, A.; Yadav, S.K.; Tailor, B.L.; Maheshwari, B. Emerging contaminants in a river receiving untreated wastewater from an Indian urban centre. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 647, 1256–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trisnawulan, I.; Suyasa, I.B.; Sundra, I.K. Analisis kualitas air sumur gali di kawasan pariwisata sanur. Ecotrophic J. Environ. Sci. 2007, 2, 385222. [Google Scholar]

- Malkani, P.; Sagar, A.; KR, A.; Singh, P.; Kumar, Y. Assessment of physico-chemical drinking water quality for surface, groundwater and effluents of industrial cluster near Kashipur and water of Kosi River. Curr. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2019, 38, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, S.; Sharma, A.; Ahmed, S.; Teotia, D. Physicochemical assessment of groundwater quality at Kashipur (Uttarakhand) industrial areas. Indian J. Geo-Mar. Sci. 2020, 49, 1486–1494. [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi, S.; Singh, P.; Sharma, B.; Singh, R. Assessment of water quality for drinking purpose in district Pauri of Uttarakhand, India. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2014, 2, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahukhandi, K.D.; Kushwaha, A.; Goswami, L.; Bhan, U.; Kamboj, V.; Kamboj, N.; Bisht, A.; Sharma, B. Hydrogeochemical Evaluation of Groundwater for Drinking and Irrigation Purposes in the Upper Piedmont Area of Haridwar, India. ACS ES&T Water 2023, 3, 1641–1653. [Google Scholar]

- Ebraheim, G.; Zonoozi, M.H.; Saeedi, M. A comparative study on the performance of NSFWQI m and IRWQI sc in water quality assessment of Sefidroud River in northern Iran. Environ. Monit. Assessment. 2020, 192, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajmohan, N. Groundwater contamination issues in the shallow aquifer, Ramganga Sub-basin, India. In Emerging Issues in the Water Environment during Anthropocene: A South East Asian Perspective; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2020; pp. 337–354. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.; Mazhar, S.N. Hydrochemical characteristics, groundwater quality and sources of solute in the ramganga aquifer, central Ganga plain, bareilly district, Uttar Pradesh. J. Geol. Soc. India 2020, 95, 616–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.K.; Siddiqui, N.A.; Gautam, A.; Khati, S. Studies of surfacewater quality of the Kashipur, Uttarakhand, India. Environ. Conserv. J. 2012, 13, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Waste Water, 22nd ed.; American Public Health Association, American Water Works Association and Water Environment Federation: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. World Health Statistics. 2012. Available online: www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2012/en/ (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- Trivedi, R.K.; Goel, P.K. Chemical and Biological Methods for Water Pollution Studies; Environmental Publication: Karad, India, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- IS:10500; Drinking Water Specifications. Bureau of Indian Standards: New Delhi, India, 2012.

- Morin-Crini, N.; Lichtfouse, E.; Liu, G.; Balaram, V.; Ribeiro, A.R.; Lu, Z.; Stock, F.; Carmona, E.; Teixeira, M.R.; Picos-Corrales, L.A.; et al. Worldwide cases of water pollution by emerging contaminants: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 2311–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouteraa, O.; Mebarki, A.; Bouaicha, F.; Nouaceur, Z.; Laignel, B. Groundwater quality assessment using multivariate analysis, geostatistical modeling, and water quality index (WQI): A case of study in the Boumerzoug-El Khroub valley of Northeast Algeria. Acta Geochim. 2019, 38, 796–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, L.A.; Allison, L.E.; Bernstein, L.; Bower, C.A.; Brown, J.W.; Fireman, M.; Hatcher, J.T.; Hayward, H.E.; Pearson, G.A.; Reeve, R.C.; et al. Diagnosis and Improvement of Saline and Alkaline Soil; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1954.

- Rotiroti, M.; Zanotti, C.; Fumagalli, L.; Taviani, S.; Stefania, G.A.; Patelli, M.; Leoni, B. Multivariate statistical analysis supporting the hydrochemical characterization of groundwater and surface water: A case study in northern Italy. Rend. Online Soc. Geol. Ital. 2019, 47, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, R.; Mohan, M.; Singh, P.; Singh, R.; Dobhal, R.; Singh, K.P.; Gupta, S. Water quality evaluation of Himalayan rivers of Kumaun region, Uttarakhand, India. Appl. Water Sci. 2016, 6, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Y.; Hu, H.; Tian, F.; Wen, J. Monitoring the spatio-temporal impact of small tributaries on the hydrochemical characteristics of Ramganga River, Ganges Basin, India. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 2020, 18, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.U.; Noor, A.; Farooqi, I.H. GIS application for groundwater management and quality mapping in rural areas of District Agra, India. Int. J. Water Res. Arid. Environ. 2015, 4, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo, S.; Kaur, A.; Litoria, P.; Pateriya, B. Geospatial modelling for groundwater quality mapping: A case study of Rupnagar district, Punjab, India. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2014, 40, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharir, K.; Pande, C.; Singh, S.K.; Choudhari, P.; Kishan, R.; Jeyakumar, L. Spatial interpolation approach-based appraisal of groundwater quality of arid regions. J. Water Supply Res. Technol.—AQUA 2019, 68, 431–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivakumar, D.; Srikantaswamy, S. Study of physico-chemical characteristics of industrial zone soil-A case study of Mysore city, Karnataka, India. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 2012, 3, 224–232. [Google Scholar]

- Sekar, K.G.; Suriyakalab, K. Seasonal variation of heavy metal and metalloids contamination of groundwater in and around Udaiyarpalyam taluk, Ariyalur district, Tamil Nadu. World Sci. News 2016, 36, 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, P.; Tiwari, A.K.; Singh, P.K. Assessment of groundwater quality of Ranchi township area, Jharkhand, India by using water quality index method. Int. J. Chem. Tech. Res. 2015, 7, 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Jadon, R.S. Measurement of Ambient Air Pollutants in the Vicinity of Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, India: Sampling, Analysis and Suggestion. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2018, 6, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, M.; Prasad, J.; Prasad, H.S. Evaluation of spring water quality using water quality index method for Bageshwar District, Uttarakhand, India. Environ. Conserv. J. 2022, 23, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, D.K.; Bhunia, G.S.; Shit, P.K.; Tiwari, A.K. Assessment of groundwater quality of the Central Gangetic Plain Area of India using Geospatial and WQI Techniques. J. Geol. Soc. India 2018, 92, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takase, Y.; Murayama, H.; Mitobe, H.; Aoki, T.; Yagoh, H.; Shibuya, N.; Shimizu, K.; Kitayama, Y. Persistent organic pollutants in rain at Niigata, Japan. Atmos. Environ. 2003, 37, 4077–4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.; Jeong, M.; Jeon, J.; Lee, H.S. The Characteristics of PM 2.5 and Acidic Air Pollutants in the Vicinity of Industrial Complexes in Gwangyang. J. Korean Soc. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 27, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, N.; Matta, G.; Bharti, M.; Kumar, A.; Kamboj, V.; Gautam, R.K. Water quality categorization using WQI in rural areas of Haridwar, India. ESSENCE Int. J. Environ. Rehabil. Conserv. 2017, 8, 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Nivetha, A.; Sakthivel, C.; Prabha, I. Heavy metal and metalloids contamination in groundwater and impact on plant and human. In Spatial Modeling and Assessment of Environmental Contaminants: Risk Assessment and Remediation; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 233–246. [Google Scholar]

- Haileslassie, T.; Gebremedhin, K. Hazards of heavy metal and metalloids contamination in ground water. Int. J. Technol. Enhanc. Emerg. Eng. Res. 2015, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, T.; Ravindra, K.; Beig, G.; Mor, S. Influence of agricultural activities on atmospheric pollution during post-monsoon harvesting seasons at a rural location of Indo-Gangetic Plain. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 796, 148903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, A.; Mushtaq, A. Untreated wastewater reasons and causes: A review of most affected areas and cities. Int. J. Chem. Biochem. Sci. 2023, 23, 121–143. [Google Scholar]

- Ponsadailakshmi, S.; Sankari, S.G.; Prasanna, S.M.; Madhurambal, G. Evaluation of water quality suitability for drinking using drinking water quality index in Nagapattinam district, Tamil Nadu in Southern India. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 6, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Raju, N.J.; Reddy, B.S.; Suresh, U.; Sankar, D.B.; Reddy, T.V. Heavy metal and metalloids contamination in river water and sediments of the Swarnamukhi River Basin, India: Risk assessment and environmental implications. Environ. Geochem. Health 2018, 40, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, R.; Bhardwaj, R.; Kumar Thukral, A.; Rodrigo-Comino, J. Assessment of heavy-metal pollution in three different Indian water bodies by combination of multivariate analysis and water pollution indices. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 2020, 26, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Raju, N.J.; Singh, N.; Sreekesh, S. Heavy metal and metalloids pollution in groundwater of urban Delhi environs: Pollution indices and health risk assessment. Urban Clim. 2022, 45, 101233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafik, A.; Bahir, M.; Beljadid, A.; Chehbouni, A.; Dhiba, D.; Ouhamdouch, S. The combination of the quality index, isotopic, and GIS techniques to assess water resources in a semi-arid context (Essaouira watershed in Morocco). Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 17, 100768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Khan, E.; Ilahi, I. Environmental chemistry and ecotoxicology of hazardous heavy metal and metalloids: Environmental persistence, toxicity, and bioaccumulation. J. Chem. 2019, 2019, 6730305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.N.; Shrivastava, R.; Mohan, D.; Kumar, P. Assessment of spatial and temporal variations in water quality dynamics of river Ganga in Varanasi. Pollution 2018, 4, 239–250. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Matta, G.; Kumar, A. Harmonizing water quality: Integrating indices and chemo-metrics for sustainable management in the Ramganga river watershed. Anal. Chem. Lett. 2024, 14, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, M.K.; Bassin, J.K. Assessing the water quality index of water treatment plant and bore wells, in Delhi, India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2010, 163, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Kumar, A.; Singh, N.; Sharma, K. Impact of seasonal variation on water quality of Hindon River: Physicochemical and biological analysis. SN Appl. Science. 2021, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.Y.; Park, S.; Kim, H.K.; Kim, M.S.; Jo, H.J.; Kim, J.I.; Lee, G.M.; Shin, I.K.; Kim, T.S. Hydrochemistry for the assessment of groundwater quality in Korea. J. Agric. Chem. Environ. 2017, 6, 72576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaitzidou, K.; Ntona, M.M.; Zavridou, E.; Tzeletas, S.; Patsialis, T.; Kallioras, A.; Zouboulis, A.; Virgiliou, C.; Mitrakas, M.; Kazakis, N. Water Quality Evaluation of Groundwater and Dam Reservoir Water: Application of the Water Quality Index to Study Sites in Greece. Water 2023, 15, 4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodapanah, L.W.; Sulaiman, W.N.; Khodapanah, N. Groundwater quality assessment for different purposes in Eshtehard District, Tehran, Iran. Eur. J. Sci. Res. 2009, 36, 543–553. [Google Scholar]

- Maiti, S.K. Handbook of Methods in Environmental Studies, 1: Water and Wastewater Analysis; ABD Publishers: Jaipur, India, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, C.; Ghosh, A.; Debnath, M.; Bhadury, P. Seasonal dynamicity of environmental variables and water quality index in the lower stretch of the River Ganga. Environ. Res. Commun. 2021, 3, 075008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matta, G.; Kumar, P.; Uniyal, D.P.; Joshi, D.U. Communicating water, sanitation, and hygiene under sustainable development goals 3, 4, and 6 as the panacea for epidemics and pandemics referencing the succession of COVID-19 surges. ACS ES&T Water 2022, 2, 667–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajmohan, N.; Amarasinghe, U.A. Groundwater quality issues and management in Ramganga Sub-Basin. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sampling Code | Sampling Locations | Site Description | Lat | Long | Source Type | Depth of Source Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GW1 | Thana Sabiq, Kashipur | Urban and Industrial | 29.219 | 78.948 | Handpump | 25–35 m |

| GW2 | Global Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research | Urban and Industrial | 29.239 | 78.897 | Borewell | 25–35 m |

| GW3 | Shree Collage of Nurshing | Urban and Industrial | 29.196 | 78.889 | Borewell | 25–35 m |

| GW4 | Kavinagar | Urban and Industrial | 29.202 | 78.951 | Borewell | 25–35 m |

| GW5 | Dharak Nagla | Rural and Agriculture Area | 29.971 | 78.821 | Borewell | 25–35 m |

| GW6 | Barahi-lalpur | Rural and Agriculture Area | 29.060 | 78.883 | Borewell | 25–35 m |

| GW7 | Ahmadpur | Rural and Agriculture Area | 28.962 | 78.809 | Handpump | 25–35 m |

| GW8 | Bhojpur | Rural and Agriculture Area | 28.954 | 78.824 | Borewell | 25–35 m |

| GW9 | Kothiwal Dental Hospital | Urban | 28.896 | 78.728 | Borewell | 25–35 m |

| GW10 | MDA colony MBD | Urban | 28.864 | 78.755 | Borewell | 25–35 m |

| GW11 | Hayatnagar MBD | Urban | 28.825 | 78.792 | Handpump | 25–35 m |

| GW12 | Pital Nagri MBD | Urban | 28.820 | 78.797 | Handpump | 25–35 m |

| GW13 | Old Shiv Mandir, Devapur—mustakam | Urban | 28.797 | 78.805 | Handpump | 25–35 m |

| Indexing | Calculation Formula | Values | Status | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groundwater Quality Index (GWQI) | Equation (2): where Ci = Observed value, Si = Standard value, Wi = Relative weight, Qi = Sub-index value, | <50 | Excellent water | [6,15] |

| 50–100 | Good water | |||

| 100–200 | Poor water | |||

| 200–300 | Very poor water | |||

| >300 | Water unsuitable for drinking | |||

| Heavy metal Pollution Index (HPI) | Equation (2): HPI where Ci = Observed value, Si = Standard value, Wi = Relative weight, Qi = Sub-index value, | 0–25 | Excellent | [8,26,27] |

| 26–50 | Good | |||

| 51–75 | Poor | |||

| >75 | Very Poor | |||

| Heavy metal Evaluation Index (HEI) | HEI where Ci = Observed value, Si = Standard value, | <40 | Low-Level Contamination | |

| 40–80 | Medium-Level Contamination | |||

| >80 | High-Level Contamination | |||

| Sodium Adsorption Ratio (SAR) | <10 | Excellent | [15,27] | |

| 10–18 | Good | |||

| 18–26 | Doubtful | |||

| >26 | Unsuitable | |||

| Sodium percentage | <20 | Excellent | [15,27] | |

| 20–40 | Good | |||

| 40–60 | Permissible | |||

| 60–80 | Doubtful | |||

| >80 | Unsuitable | |||

| Health Risk Index | Equation (1): Equation (2): HQ = Equation (3): HI = where ADDoral = Average Daily Dose though oral, Cw = observed concentration, IR: Ingestion rate, EF = Exposure Frequency, ED = Exposure duration, BW= Body Weight, AT = Average Time, HQ = Hazard Quotient, RfD = Reference Dose, HI = Health Index | 0 < HI < 1 | No Risk | [6,15] |

| 1 < HI < 5 | Low Risk | |||

| 5 < HI < 10 | Moderate Risk | |||

| HI > 10 | High Risk |

| Parameters | Symbol | Unit | Pre-Monsoon | Post-Monsoon | BIS (2012) and WHO (2017) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Average ± S.D. | Min | Max | Average ± S.D. | ||||

| pH | 7.16 | 7.35 | 7.26 ± 0.06 | 7.19 | 7.27 | 7.23 ± 0.03 | 6.5–8.5 | ||

| Total Dissolved Solids | TDS | mg/L | 265.33 | 360.67 | 301.59 ± 28.07 | 285.33 | 335.33 | 301.97 ± 14.94 | 500 |

| Total Hardness | TH | mg/L | 184.36 | 235.65 | 207.57 ± 12.54 | 189.58 | 214.22 | 201.83 ± 6.42 | 300 |

| Alkalinity | A | mg/L | 227.08 | 293.22 | 256.13 ± 17.66 | 256.29 | 299.97 | 270.56 ± 14.06 | 250 |

| Acidity | AC | mg/L | 19.96 | 40.49 | 26.57 ± 5.83 | 21.19 | 38.41 | 25.50 ± 5.59 | -- |

| Bicarbonates | HCO3− | mg/L | 189.77 | 230.62 | 208.34 ± 12.63 | 201.22 | 231.18 | 212.94 ± 9.31 | 244 |

| Nitrates | NO3− | mg/L | 0.87 | 1.45 | 1.21 ± 0.19 | 0.84 | 1.29 | 1.10 ± 0.14 | 45 |

| Phosphate | PO43− | mg/L | 0.73 | 2.76 | 1.87 ± 0.74 | 0.95 | 2.31 | 1.63 ± 0.48 | 01 |

| Sulphate | SO42− | mg/L | 23.67 | 52.33 | 33.66 ± 12.27 | 23.23 | 44.31 | 31.10 ± 8.50 | 200 |

| Chloride | Cl− | mg/L | 20.58 | 49.89 | 32.63 ± 10.84 | 22.16 | 45.00 | 30.98 ± 8.89 | 250 |

| Calcium | Ca2+ | mg/L | 114.97 | 141.65 | 126.29 ± 8.02 | 114.88 | 137.82 | 123.61 ± 6.92 | 75 |

| Magnesium | Mg2+ | mg/L | 18.83 | 37.22 | 26.07 ± 4.96 | 19.51 | 35.15 | 25.69 ± 4.35 | 30 |

| Sodium | Na+ | mg/L | 21.13 | 39.97 | 30.70 ± 6.31 | 22.18 | 34.19 | 28.61 ± 4.20 | 200 |

| Potassium | K+ | mg/L | 2.32 | 7.39 | 4.04 ± 1.59 | 3.01 | 5.88 | 4.48 ± 1.18 | 10 |

| Zinc | Zn | mg/L | 0.309 | 1.787 | 1.004 ± 0.524 | 0.613 | 1.633 | 1.122 ± 0.346 | 5 |

| Iron | Fe | mg/L | 0.290 | 0.965 | 0.560 ± 0.270 | 0.253 | 1.720 | 0.515 ± 0.397 | 0.3 |

| Cadmium | Cd | mg/L | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 ± 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 ± 0.001 | 0.003 |

| Arsenic | As | mg/L | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 ± 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 ± 0.001 | 0.01 |

| Chromium | Cr | mg/L | 0.009 | 0.027 | 0.019 ± 0.007 | 0.011 | 0.029 | 0.021 ± 0.005 | 0.05 |

| Lead | Pb | mg/L | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.005 ± 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.010 | 0.004 ± 0.004 | 0.05 |

| Sampling Location | Pre-Monsoon | Post-Monsoon | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GWQI | GWQI | |||

| Value | Status | Value | Status | |

| GW1 | 41.639 | Excellent Water | 43.091 | Excellent Water |

| GW2 | 42.243 | Excellent Water | 43.752 | Excellent Water |

| GW3 | 45.380 | Excellent Water | 43.377 | Excellent Water |

| GW4 | 46.384 | Excellent Water | 46.500 | Excellent Water |

| GW5 | 50.173 | Good Water | 48.108 | Excellent Water |

| GW6 | 53.139 | Good Water | 50.426 | Good Water |

| GW7 | 54.837 | Good Water | 53.692 | Good Water |

| GW8 | 56.326 | Good Water | 53.902 | Good Water |

| GW9 | 44.303 | Excellent Water | 45.759 | Excellent Water |

| GW10 | 48.293 | Excellent Water | 48.219 | Excellent Water |

| GW11 | 51.305 | Good Water | 48.091 | Excellent Water |

| GW12 | 52.208 | Good Water | 48.788 | Excellent Water |

| GW13 | 52.043 | Good Water | 48.715 | Excellent Water |

| Min | 41.639 | Excellent Water | 43.091 | Excellent Water |

| Max | 56.326 | Good Water | 53.902 | Good Water |

| Mean ± S.D. | 49.098 ± 4.773 | Excellent Water | 47.878 ± 3.475 | Excellent Water |

| Sampling Location | Pre-Monsoon | Post-Monsoon | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPI | HEI | HPI | HEI | |||||

| Value | Status | Value | Status | Value | Status | Value | Status | |

| GW1 | 30.45 | Good | 1.17 | Low Level | 58.30 | Poor | 1.20 | Low Level |

| GW2 | 29.97 | Good | 1.03 | Low Level | 30.03 | Good | 1.13 | Low Level |

| GW3 | 39.44 | Good | 1.24 | Low Level | 58.97 | Poor | 1.35 | Low Level |

| GW4 | 59.80 | Poor | 2.41 | Low Level | 30.54 | Good | 1.69 | Low Level |

| GW5 | 59.69 | Poor | 2.54 | Low Level | 59.18 | Poor | 2.09 | Low Level |

| GW6 | 59.83 | Poor | 2.57 | Low Level | 59.65 | Poor | 2.32 | Low Level |

| GW7 | 60.26 | Poor | 2.31 | Low Level | 59.75 | Poor | 2.15 | Low Level |

| GW8 | 30.84 | Good | 1.72 | Low Level | 30.64 | Good | 1.73 | Low Level |

| GW9 | 29.51 | Good | 1.11 | Low Level | 30.50 | Good | 1.36 | Low Level |

| GW10 | 30.18 | Good | 1.17 | Low Level | 30.20 | Good | 1.22 | Low Level |

| GW11 | 30.28 | Good | 1.25 | Low Level | 30.30 | Good | 1.25 | Low Level |

| GW12 | 59.22 | Poor | 2.01 | Low Level | 30.81 | Good | 2.01 | Low Level |

| GW13 | 60.12 | Poor | 2.32 | Low Level | 59.46 | Poor | 3.37 | Low Level |

| Min | 29.51 | Good | 1.03 | Low Level | 30.03 | Good | 1.13 | Low Level |

| Max | 60.26 | Poor | 2.57 | Low Level | 59.75 | Poor | 3.37 | Low Level |

| Mean ± S.D. | 44.58 ±14.89 | Good | 1.74 ± 0.62 | Low Level | 43.72 ± 14.94 | Good | 1.76 ± 0.63 | Low Level |

| Sampling Location | Pre-Monsoon | Post-Monsoon | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAR | % Na | SAR | % Na | |||||

| Value | Status | Value | Status | Value | Status | Value | Status | |

| GW1 | 2.53 | Excellent | 14.39 | Excellent | 2.67 | Excellent | 15.40 | Excellent |

| GW2 | 2.64 | Excellent | 14.82 | Excellent | 2.96 | Excellent | 16.48 | Excellent |

| GW3 | 3.72 | Excellent | 19.89 | Excellent | 3.65 | Excellent | 19.67 | Excellent |

| GW4 | 3.63 | Excellent | 19.13 | Excellent | 3.86 | Excellent | 20.73 | Good |

| GW5 | 4.24 | Excellent | 21.52 | Good | 4.00 | Excellent | 20.48 | Good |

| GW6 | 4.28 | Excellent | 21.25 | Good | 3.92 | Excellent | 20.59 | Good |

| GW7 | 3.00 | Excellent | 15.22 | Excellent | 3.52 | Excellent | 18.17 | Excellent |

| GW8 | 3.53 | Excellent | 17.81 | Excellent | 3.34 | Excellent | 17.52 | Excellent |

| GW9 | 2.80 | Excellent | 15.21 | Excellent | 3.29 | Excellent | 17.74 | Excellent |

| GW10 | 2.91 | Excellent | 15.47 | Excellent | 3.23 | Excellent | 17.10 | Excellent |

| GW11 | 3.46 | Excellent | 19.03 | Excellent | 2.79 | Excellent | 17.02 | Excellent |

| GW12 | 4.41 | Excellent | 23.18 | Good | 2.81 | Excellent | 16.87 | Excellent |

| GW13 | 4.59 | Excellent | 23.10 | Good | 3.01 | Excellent | 17.63 | Excellent |

| Min | 2.53 | Excellent | 14.39 | Excellent | 2.67 | Excellent | 15.40 | Excellent |

| Max | 4.59 | Excellent | 23.18 | Good | 4.00 | Excellent | 20.73 | Good |

| Mean ± S.D. | 3.52 ± 0.71 | Excellent | 18.46 ± 3.21 | Excellent | 3.31 ± 0.45 | Excellent | 18.11 ± 1.72 | Excellent |

| Sampling Location | Pre-Monsoon | Post-Monsoon | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infant | Child | Adults | Infant | Child | Adults | |||||||

| Total Health Index | Status | Total Health Index | Status | Total Health Index | Status | Total Health Index | Status | Total Health Index | Status | Total Health Index | Status | |

| G1 | 2.13 | Low Risk | 5.02 | Medium Risk | 5.23 | Medium Risk | 2.09 | Low Risk | 4.92 | Low Risk | 5.13 | Medium Risk |

| G2 | 1.77 | Low Risk | 4.16 | Low Risk | 4.33 | Low Risk | 1.95 | Low Risk | 4.59 | Low Risk | 4.79 | Low Risk |

| G3 | 1.99 | Low Risk | 4.68 | Low Risk | 4.88 | Low Risk | 2.31 | Low Risk | 5.43 | Medium Risk | 5.66 | Medium Risk |

| G4 | 4.12 | Low Risk | 9.69 | Medium Risk | 10.10 | High Risk | 2.37 | Low Risk | 5.57 | Medium Risk | 5.80 | Medium Risk |

| G5 | 4.20 | Low Risk | 9.87 | Medium Risk | 10.29 | High Risk | 3.19 | Low Risk | 7.51 | Medium Risk | 7.82 | Medium Risk |

| G6 | 4.19 | Low Risk | 9.84 | Medium Risk | 10.26 | High Risk | 3.77 | Low Risk | 8.85 | Medium Risk | 9.23 | Medium Risk |

| G7 | 3.91 | Low Risk | 9.19 | Medium Risk | 9.58 | Medium Risk | 3.42 | Low Risk | 8.04 | Medium Risk | 8.38 | Medium Risk |

| G8 | 3.00 | Low Risk | 7.06 | Medium Risk | 7.36 | Medium Risk | 3.02 | Low Risk | 7.10 | Medium Risk | 7.40 | Medium Risk |

| G9 | 1.55 | Low Risk | 3.65 | Low Risk | 3.80 | Low Risk | 2.18 | Low Risk | 5.13 | Medium Risk | 5.35 | Medium Risk |

| G10 | 1.51 | Low Risk | 3.54 | Low Risk | 3.69 | Low Risk | 1.55 | Low Risk | 3.65 | Low Risk | 3.80 | Low Risk |

| G11 | 1.52 | Low Risk | 3.56 | Low Risk | 3.71 | Low Risk | 1.52 | Low Risk | 3.57 | Low Risk | 3.72 | Low Risk |

| G12 | 2.73 | Low Risk | 6.41 | Medium Risk | 6.68 | Medium Risk | 2.56 | Low Risk | 6.02 | Medium Risk | 6.27 | Medium Risk |

| G13 | 3.31 | Low Risk | 7.78 | Medium Risk | 8.11 | Medium Risk | 5.99 | Medium Risk | 14.07 | High Risk | 14.67 | High Risk |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kumar, P.; Matta, G.; Kumar, A.; Pant, G. Groundwater Quality and Potential Health Risk Assessment for Potable Use. World 2024, 5, 805-831. https://doi.org/10.3390/world5040042

Kumar P, Matta G, Kumar A, Pant G. Groundwater Quality and Potential Health Risk Assessment for Potable Use. World. 2024; 5(4):805-831. https://doi.org/10.3390/world5040042

Chicago/Turabian StyleKumar, Pawan, Gagan Matta, Amit Kumar, and Gaurav Pant. 2024. "Groundwater Quality and Potential Health Risk Assessment for Potable Use" World 5, no. 4: 805-831. https://doi.org/10.3390/world5040042

APA StyleKumar, P., Matta, G., Kumar, A., & Pant, G. (2024). Groundwater Quality and Potential Health Risk Assessment for Potable Use. World, 5(4), 805-831. https://doi.org/10.3390/world5040042