Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behavior Regarding Health and Environment in an Israeli Community: Implications for Sustainable Urban Environments and Public Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Research Tool

- Demographic data—This section contained eleven questions regarding participants’ gender, age, marital status, number of people in their household, number of children aged under 18 years old, religiosity, education, country of birth, dietary habits, socioeconomic status, and neighborhood of residence.

- Attitudes—This section contained ten statements (see Table 2). Participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement with each statement on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The variable was constructed by calculating the mean score for each participant after reversing the scales for statements 3 and 9, with a higher score indicating a more positive attitude toward the environmental protection.

- Knowledge—This section of the questionnaire contained ten statements (see Table 3). Participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement with each statement on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The variable was constructed by calculating the mean score for each participant, with a higher score indicating a higher level of knowledge.

- Behavior—This section of the questionnaire had ten statements (see Table 4). Participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement with each statement on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The variable was constructed by calculating the mean score for each participant after reversing the scale for statement 6, with a higher score indicating more environmentally friendly behavior.

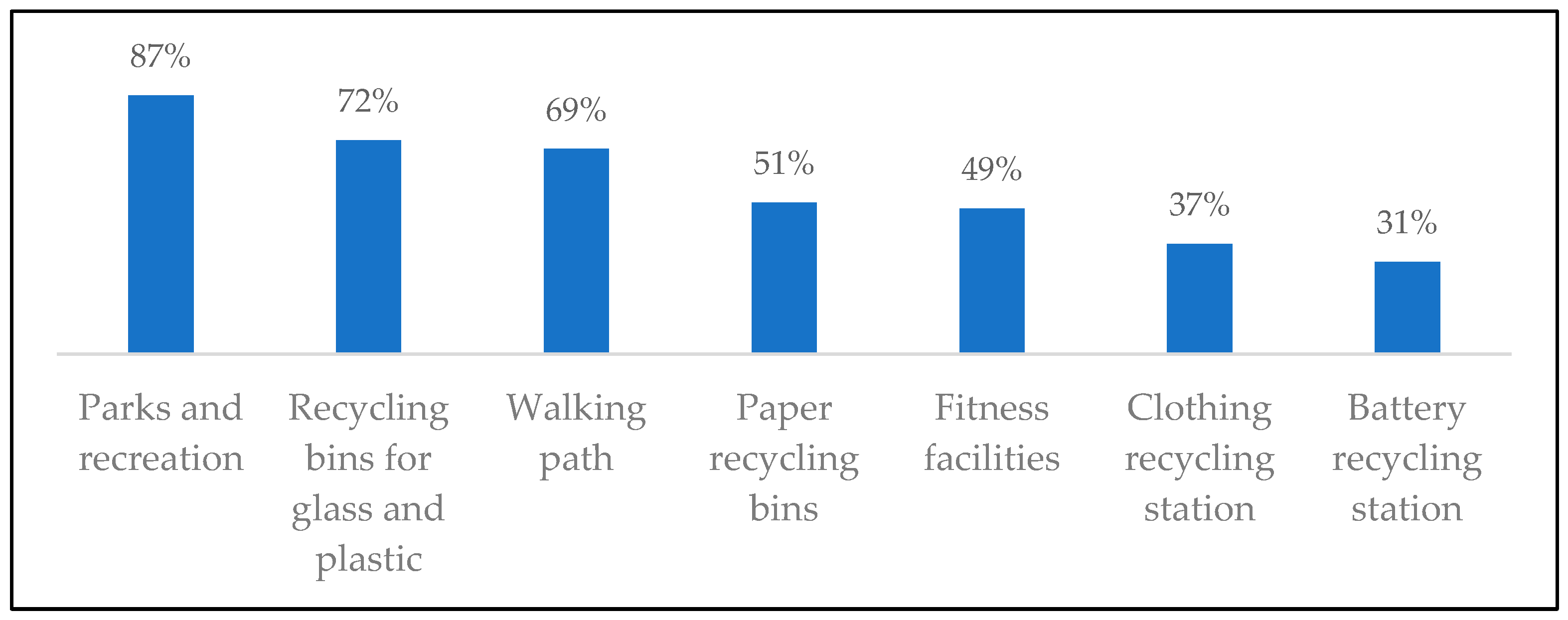

- Accessibility of facilities beneficial to the environment or public health (hereafter referred to as “facilities”)—Participants were asked to indicate whether the following facilities were available near their residence: clothing recycling stations, battery recycling stations, paper recycling bins, plastic and glass recycling bins, walking paths/trails, parks and playgrounds, and fitness facilities. The variable was constructed by counting the positive responses. The variable could vary between 0 and 7, with a higher score indicating accessibility to more facilities near the participant’s residence.

- Participants were also asked an open-ended question: “In your opinion, how can the municipal authority contribute to environmental conservation?”.

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Attitudes

3.3. Knowledge

3.4. Behavior

3.5. Accessibility of Facilities near Participants’ Place of Residence

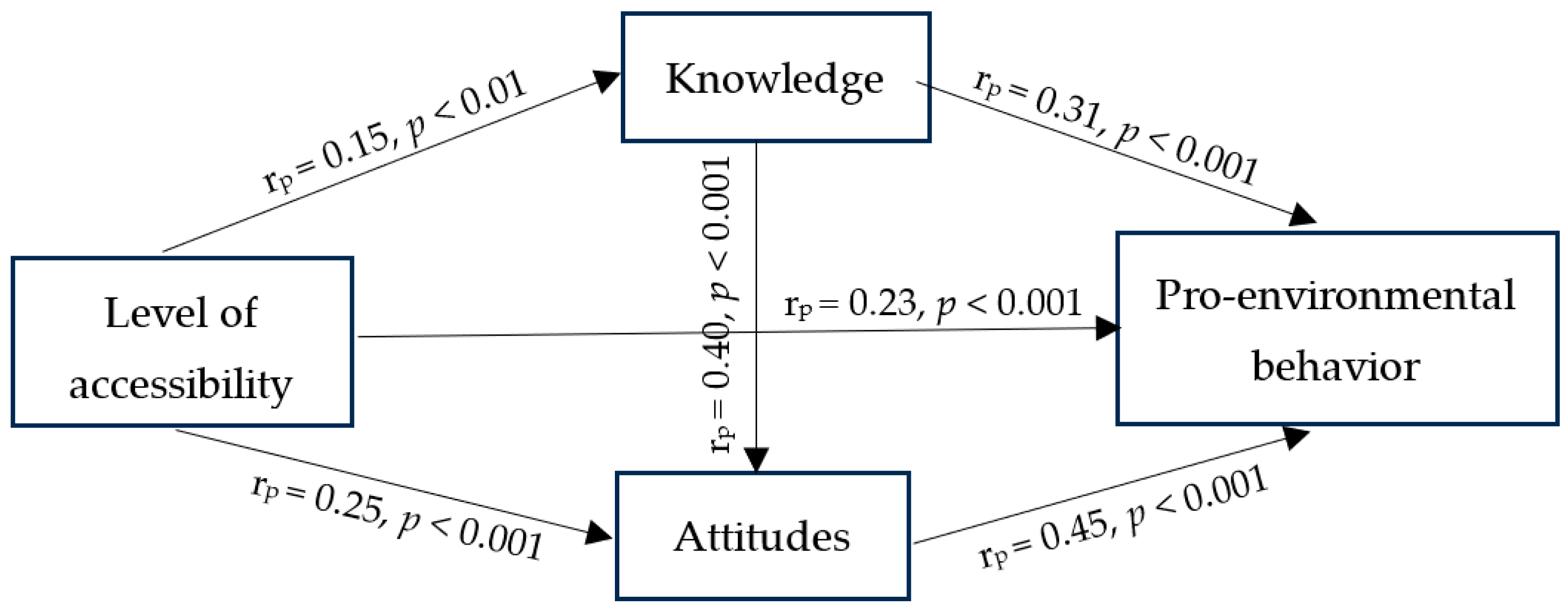

3.6. Relationships between the Variables

3.7. Additional Findings

- Gender—No significant differences were found between males and females in relation to their level of knowledge, reported behavior, and level of awareness regarding the accessibility of facilities near to their place of residence. However, significant differences were found between males and females regarding their attitudes to the environment (t(319) = 4.33, p < 0.001), with women having more positive attitudes compared to men (averages of 3.95 vs. 3.65, respectively).

- Age—The older the participants, the more positive their attitudes to the environment (rp = 0.15, p < 0.01), the more pro-environmental their reported behavior (rp = 0.20, p < 0.001), and the greater their level of awareness regarding the accessibility of facilities near to their place of residence (rp = 0.12, p < 0.05).

- Level of religiosity—No significant differences were found between the levels of religiosity in relation to the study variables.

- Number of people living in the household—The more people there were living in a household, the less pro-environmental their reported behavior (rp = −0.22, p < 0.001).

- Level of education—The higher the level of education, the more positive the attitudes to the environment (rs = 0.14, p < 0.05), the higher their level of knowledge (rs = 0.28, p < 0.001), and the more pro-environmental their reported behavior (rs = 0.11, p < 0.05).

- Pet ownership—Significant differences were found between participants who currently owned pets or who had owned pets in the past and participants who hadn’t experienced pet ownership, in terms of both attitudes (t(317) = 3.11, p < 0.001), with the former having more positive attitudes (averages 3.37 vs. 3.15, respectively), and in terms of reported behavior (t(292) = 1.67, p < 0.05), with participants who had owned pets reporting more pro-environmental behavior (averages 3.39 vs. 3.28, respectively).

3.8. Regression Model to Predict Pro-Environmental Behavior

3.9. How the Municipal Authority Can Help Protect the Environment

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Portney, K.; Sansom, G. Sustainable cities and healthy cities: Are they the same? Urban Plan. 2017, 2, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilian, B.; Wang, B.; Lewis, K.; Duarte, F.; Ratti, C.; Behdad, S. The future of waste management in smart and sustainable cities: A review and concept paper. Waste Manag. 2018, 81, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, E.-H.; Lee, H.; Kang, M.-J.; Nam, I.; Moon, H.-K.; Sung, J.-W.; Eu, J.-Y.; Lee, H.-B. Factors Affecting Zero-Waste Behaviours of College Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, N.; Marquès, M.; Nadal, M.; Domingo, J.L. Meat consumption: Which are the current global risks? A review of recent (2010–2020) evidences. Food Res Int. 2020, 137, 109341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopelt, K.; Radon, P.; Davidovitch, N. Environmental Effects of the Livestock Industry: The Relationship between Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behavior among Students in Israel. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, M.; Lloyd, S.; Haines, A.; Ding, D.; Hutchinson, E.; Belesova, K.; Davies, M.; Osrin, D.; Zimmermann, N.; Capon, A.; et al. Transforming cities for sustainability: A health perspective. Environ. Int. 2021, 147, 106366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, A. The green city citizen: Exploring the ambiguities of sustainable lifestyles in Copenhagen. Environ. Policy Gov. 2018, 29, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron-Epel, A.; Paldi, Y.; Rubin, L.; Bord, S.; Berkowitz, A.; Rudolph, M.; Hasson, R.; Sahar, Y.; Manor, N. The “Healthy Family” (HENRY) Program in Israel: Findings, insights, and conclusions for the program’s continued implementation. Health Promot. Isr. 2020, 7, 6–16. [Google Scholar]

- NASA (The National Aeronautics and Space Administration). Climate Change: How Do We Know? Global Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet. 2019. Available online: https://climate.nasa.gov/evidence/ (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Dockrill, P. It’s Official: Atmospheric CO2 just Exceeded 415 ppm for the First Time in Human History. 2019. Available online: https://www.sciencealert.com/it-s-official-atmospheric-co2-just-exceeded-415-ppm-for-first-time-in-human-history (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Hörcher, D.; Graham, D.J. Pricing and Efficient Public Transport Supply in a Mobility as a Service Context. Int. Transp. Forum Discuss. 2020. Paper No. 2020/15. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/245846/1/1741923980.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Santana, J.C.C.; Miranda, A.C.; Yamamura, C.L.K.; Silva Filho, S.C.d.; Tambourgi, E.B.; Lee Ho, L.; Berssaneti, F.T. Effects of Air Pollution on Human Health and Costs: Current Situation in São Paulo, Brazil. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdem, Y.; Dal, B.; Sönmez, D.; Alper, U. What is that thing called climate change? an investigation into the understanding of climate change by seventh-grade students. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2014, 23, 294–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopelt, K.; Loren, O.; Gapich, G.; Davidovitch, N. Moving from indifference to responsibility: Reframing environmental behavior among college students in Israel. Front. Clim. 2021, 3, 776930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T. The interplay between knowledge, perceived efficacy, and concern about global warming and climate change: A one-year longitudinal study. Risk Anal. 2012, 32, 1003–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, K.; Peterson, N.; Bondell, H. The influence of personal beliefs, friends, and family in building climate change concern among adolescents. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 832–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonoli, A.; Zanni, S.; Serrano-Bernardo, F. Sustainability in Building and Construction within the Framework of Circular Cities and European New Green Deal. The Contribution of Concrete Recycling. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Bureau of Statistics. Settlements and Other Geographical Divisions. 2022. Available online: https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/settlements/Pages/default.aspx?subject=%D7%90%D7%95%25D (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Kumar, R.; Verma, A.; Shome, A.; Sinha, R.; Sinha, S.; Jha, P.K.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, P.; Shubham; Das, S.; et al. Impacts of Plastic Pollution on Ecosystem Services, Sustainable Development Goals, and Need to Focus on Circular Economy and Policy Interventions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, D.; Sinatra, G. College students’ perceptions about the plausibility of human-induced climate change. Res. Sci. Educ. 2012, 42, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liao, W.; Liu, C.; Zhang, N.; Zhong, S.; Huang, C. Associations between Knowledge of the Causes and Perceived Impacts of Climate Change: A Cross-Sectional Survey of Medical, Public Health and Nursing Students in Universities in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, S.L.; Chiarella, S.G.; Raffone, A.; Simione, L. Understanding the Environmental Attitude-Behaviour Gap: The Moderating Role of Dispositional Mindfulness. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carducci, A.; Fiore, M.; Azara, A.; Bonaccorsi, G.; Bortoletto, M.; Caggiano, G.; Calamusa, A.; De Donno, A.; De Giglio, O.; Dettori, M.; et al. Pro-Environmental Behaviors: Determinants and Obstacles among Italian University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negev, M.; Sagy, G.; Garb, Y.; Salzberg, A.; Tal, A. Evaluating the environmental literacy of Israeli elementary and high school students. J. Environ. Educ. 2008, 39, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, E.; Worsley, A. Australian consumers’ food-related environmental beliefs and behaviors. Appetite 2008, 50, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dori, Y.J.; Tal, T. Industry-environment projects: Formal and informal science activities in a community school. Sci. Educ. 2000, 84, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickinson, M. Learners and learning in environment education: A critical review of the evidence. Environ. Educ. Res. 2001, 7, 207–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlemeier, H.; Van Den Bergh, H.; Lagerweij, N. Environmental knowledge, attitudes, and behavior in Dutch secondary education. J. Environ. Educ. 2010, 30, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, A.; Ray, J. Fewer Americans, Europeans View Global Warming as a Threat. 2011. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/poll/147203/fewer-americans-europeans-view-global-warming-threat.aspx (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- María, R.D.; Díaz, I.; Rodríguez, M.; Sáiz, A. Industrial methanol from syngas: Kinetic Study and process simulation. Int. J. Chem. React. Eng. 2013, 11, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.-T.; Lien, C.-Y.; Huang, Y.-W.; Han, G.; Shyu, G.-S.; Chou, J.-Y.; Ng, E. Environmental Literacy on Ecotourism: A Study on Student Knowledge, Attitude, and Behavioral Intentions in China and Taiwan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. 1986. Available online: https://www.healthpromotion.org.au/images/ottawa_charter_hp.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Keyes, K.M.; Galea, S. Population Health Science; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Social Justice Association Public Attitudes on Climate Change in Israel and Worldwide, as Part of the “Climate, Society and Economy” Policy Research Project. 2015. Available online: http://www.aeji.org.il/content/%D7%A2%D7%9E%D7%93%D7%95%D7%AA-%D7%94%D7%A6%D7%99%D7%91%D7%95%D7%A8-%D7%91%D7%A0%D7%95%D7%A9%D7%90-%D7%90%D7%A7%D7%9C%D7%99%D7%9D-%D7%91%D7%99%D7%A9%D7%A8%D7%90%D7%9C-%D7%95%D7%91%D7%A2%D7%95%D7%9C%D7%9D (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Wang, Y.; Hao, F.; Liu, Y. Pro-Environmental Behavior in an Aging World: Evidence from 31 Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pifer, L.; Shimizu, K.; Pifer, R. Public attitudes toward animal research: Some international comparisons. Soc. Anim. 1994, 2, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart Cities Dive. Ten Cities Tackling Climate Change. 2024. Available online: https://www.smartcitiesdive.com/ex/sustainablecitiescollective/10-cities-tackling-climate-change/178136/ (accessed on 4 April 2024).

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 69 | 21 |

| Female | 253 | 79 |

| Marital status: | ||

| Married, living with a partner | 242 | 75 |

| Single | 48 | 15 |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 32 | 10 |

| Number of people living in the household: | ||

| Living alone | 30 | 9 |

| 2 people | 87 | 27 |

| 3–4 people | 105 | 33 |

| 4 or more people | 100 | 31 |

| Have children under the age of 18 | 173 | 54 |

| Level of religiosity: | ||

| Secular | 182 | 57 |

| Traditional | 85 | 26 |

| Religious | 54 | 17 |

| Level of education: | ||

| High school | 57 | 18 |

| Vocational high school | 91 | 28 |

| Higher education | 173 | 54 |

| Nutrition: | ||

| Omnivore | 285 | 88 |

| Vegetarian/vegan | 37 | 12 |

| Currently own or have previously owned a pet | 191 | 60 |

| Country of birth: | ||

| Israel | 226 | 70 |

| Former USSR countries | 74 | 23 |

| Other | 22 | 7 |

| Statement | Weakly Agree (%) | Moderately Agree (%) | Strongly Agree (%) | Don’t Know (%) | Mean ± SD 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. It is important to preserve the quality of the environment | 2 | 3 | 94 | 1 | 4.67 ± 0.66 |

| 2. Products made from recyclable materials should be used, even if they are more expensive | 15 | 49 | 35 | 1 | 3.52 ± 0.97 |

| 3. The amounts of waste do not affect me directly * | 26 | 24 | 48 | 2 | 3.36 ± 1.26 |

| 4. I feel uncomfortable producing plastic waste | 12 | 27 | 60 | 1 | 3.68 ± 1.03 |

| 5. If I had more knowledge on the subject, I would incorporate environmental considerations into my food choices | 10 | 18 | 72 | 0 | 4.03 ± 1.09 |

| 6. It is important to me to use up leftover food | 12 | 16 | 71 | 1 | 3.86 ± 1.06 |

| 7. I am aware of the amount of waste my household produces | 23 | 22 | 54 | 1 | 3.47 ± 1.17 |

| 8. It is important to me that the products I consume are produced in a way that preserves the rights of the animals | 11 | 15 | 72 | 2 | 3.96 ± 1.04 |

| 9. The general concern for environmental problems [is not] excessive * | 15 | 16 | 67 | 2 | 3.90 ± 1.28 |

| 10. I think that human behavior affects climate change | 3 | 8 | 87 | 2 | 4.53 ± 0.80 |

| Statement | Weakly Agree (%) | Moderately Agree (%) | Strongly Agree (%) | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I understand the connection between the environment and human health | 2 | 21 | 77 | 3.97 ± 0.75 |

| 2. I know how to choose healthy food | 21 | 33 | 46 | 3.35 ± 0.99 |

| 3. I know how waste is recycled | 45 | 26 | 29 | 2.74 ± 1.24 |

| 4. I know the damage that plastic causes to the environment | 19 | 32 | 49 | 3.48 ± 1.02 |

| 5. I know the damage caused to the environment by the livestock industry | 38 | 27 | 35 | 2.99 ± 1.15 |

| 6. I know what is meant by the term “zero waste” | 49 | 30 | 21 | 2.56 ± 1.22 |

| 7. I know what is meant by the term “One Health” | 47 | 34 | 19 | 2.55 ± 1.16 |

| 8. Humans are primarily responsible for climate change | 8 | 18 | 74 | 3.82 ± 0.86 |

| 9. I understand how much the climate crisis affects health | 7 | 24 | 69 | 3.78 ± 0.83 |

| 10. You can save electricity and reduce environmental pollution | 11 | 34 | 55 | 3.61 ± 0.91 |

| Statement | Weakly Agree (%) | Moderately Agree (%) | Strongly Agree (%) | Don’t Know (%) | Mean ± SD 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Uses environmentally friendly products | 12 | 29 | 38 | 21 | 3.45 ± 0.98 |

| 2. Puts plastic in the recycling bins | 37 | 20 | 37 | 6 | 2.98 ± 1.46 |

| 3. Uses reusable cloth bags/baskets | 15 | 13 | 79 | 3 | 3.95 ± 1.21 |

| 4. Considers installing solar panels in the house/building | 35 | 12 | 21 | 32 | 2.61 ± 1.42 |

| 5. Make sure to buy only what is needed | 10 | 18 | 69 | 3 | 3.97 ± 1.08 |

| 6. [No] ordering/buying home-prepared food * | 16 | 35 | 47 | 2 | 3.39 ± 1.04 |

| 7. Eats family meals at least three times a week | 17 | 21 | 59 | 3 | 3.60 ± 1.11 |

| 8. Household members usually eat vegetables and fruits | 3 | 13 | 81 | 3 | 4.22 ± 0.79 |

| 9. Tries to consume less chicken and meat products | 37 | 36 | 23 | 4 | 2.86 ± 1.19 |

| 10. Considers switching to a vegetarian or vegan diet | 66 | 9 | 18 | 7 | 2.13 ± 1.39 |

| Variable | B | β | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (0—male, 1—female) | 0.26 | 0.18 | <0.001 |

| Age | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.045 |

| Knowledge | 0.24 | 0.26 | <0.001 |

| Attitudes | 0.48 | 0.42 | <0.001 |

| Level of accessibility | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.071 |

| Adjusted R Square | 0.35, p < 0.001 | ||

| F | 32.64, p < 0.001 | ||

| N | 295 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dopelt, K.; Aharon, L.; Rimon, M. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behavior Regarding Health and Environment in an Israeli Community: Implications for Sustainable Urban Environments and Public Health. World 2024, 5, 645-658. https://doi.org/10.3390/world5030033

Dopelt K, Aharon L, Rimon M. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behavior Regarding Health and Environment in an Israeli Community: Implications for Sustainable Urban Environments and Public Health. World. 2024; 5(3):645-658. https://doi.org/10.3390/world5030033

Chicago/Turabian StyleDopelt, Keren, Liza Aharon, and Miri Rimon. 2024. "Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behavior Regarding Health and Environment in an Israeli Community: Implications for Sustainable Urban Environments and Public Health" World 5, no. 3: 645-658. https://doi.org/10.3390/world5030033

APA StyleDopelt, K., Aharon, L., & Rimon, M. (2024). Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behavior Regarding Health and Environment in an Israeli Community: Implications for Sustainable Urban Environments and Public Health. World, 5(3), 645-658. https://doi.org/10.3390/world5030033