Abstract

This paper presents an overview of how the Community-led Local Development (CLLD) instrument has been used in the EU in the 2014–2020 programming period. It provides a typology of countries applying the options offered by CLLD and illustrates the various ways in which the different eligible EU funds were contributing financially. The article discusses the experiences made with CLLD implementation, focusing on the purpose for which CLLD was implemented, the barriers encountered, and the achievements so far. A particular look is taken at the urban dimension of CLLD as one of the innovative elements of the 2014–2020 programming period. Overall, CLLD can bring significant added value for the targeted territories and can foster an increased policy integration. However, challenges remain, particularly around administrative complexities, and these impact on the willingness of policy-makers to make use of the full range of options offered by CLLD. Indeed, looking into 2021–2027, there are countries discontinuing CLLD, but, at the same time, the CLLD model is being expanded where experiences have been predominantly positive.

1. Introduction

Local development has different faces across the EU. Probably its most structured form is “Community-led Local Development” (CLLD), which was introduced in the 2014–2020 programming period. It was implemented initially as the LEADER approach [1] as part of EU rural development funding since 1991 and has since expanded to include the option to also be funded from other EU funds, including maritime and fisheries, social, and regional. The extent to which the new opportunities are used varies significantly across European countries and regions, and so do the experiences made with the application of these new forms of CLLD. This paper takes stock of these implementation experiences, giving an overview of the extent to which the CLLD instrument has been adopted across the EU in the 2014–2020 programming period and illustrates the experience made with it. It is structured to present the uptake of CLLD, its sources of funding and the experiences made with CLLD implementation. It then highlights the specific experiences of urban CLLD and presents some lessons learned, before providing an outlook for the 2021–2027 programming period.

2. Context

Since its introduction in 1991, LEADER (Liaison Entre Actions de Développement de l’Économie Rurale) has managed to establish itself as the key local development framework in Europe. According to Copus and Dax [2], the successful LEADER approach has proved to be a powerful tool to develop rural areas by supporting innovation among local actors. Indeed, LEADER can be understood as a form of innovation policy in rural areas [3], strongly the focused on social innovation [4]. Although LEADER was originally designed for the rural context, it was then extended as “Community-led Local Development” (CLLD) to include coastal (2007) and urban (2014) areas. However, it has maintained the key features of the original LEADER method, i.e., area-based development strategies; bottom-up elaboration and implementation of strategies; local public–private partnerships (local action groups); integrated and multi-sector actions; innovation; cooperation; and networking.

Only the rural version of CLLD—generally known as “LEADER”—is mandatory; the application of CLLD in coastal or urban contexts is optional. Thus, we can find a variety of models across the EU, with each Member State having a specific configuration of local development approaches and funding sources, targeting various types of areas and beneficiaries, and using different governance systems.

Furthermore, CLLD can be supported by a single European Structural and Investment (ESI) fund or by a combination of any of the four eligible funds, namely the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD), the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF), the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), and the European Social Fund (ESF). Where CLLD is co-funded only by the EAFRD, it is typically referred to as LEADER. In all cases, each CLLD strategy is implemented by a Local Action Group (LAG), which is a partnership of local public, private, and community representatives responsible for the implementation of CLLD in their areas.

3. Results

3.1. Uptake of CLLD in Europe

The LEADER approach has been continuously expanding since its introduction in 1991, with the number of LAGs growing in each programming period (Table 1). While a significant share of the growth can be attributed to EU enlargement, at the same time, the territorial coverage of LAGs has also been continuously expanding in existing EU Member States.

Table 1.

Evolution and expansion of the LEADER approach into CLLD.

Without any EU enlargement, the 2014–2020 EU programming period saw a further increase in the number of LAGs by over 50%. This resulted in a territorial coverage of close to 100% in some countries (e.g., Portugal, Slovenia). Partly, this increase is also due to the addition of newly eligible urban territories for CLLD (see Section 5).

There is no common model of CLLD implementation. Instead, there are a variety of models in the different EU Member States and regions, ranging from a conservative approach of continuing models established in the 2007–2013 programming period (and before), to models in which the opportunities to use a wider range of funding sources for bottom-up local development have been picked up.

In 2022, there were 3333 LAGs in the EU (Table 2). However, uptake of the new CLLD model, i.e., the use for CLLD in funds other than rural and fisheries, was limited, and the vast majority of LAGs (2535 or 76%) were only implementing EAFRD and/or EMFF. Only 798 LAGs in 16 Member States were using CLLD as an implementation mechanism for cohesion policy funding, i.e., ERDF or ESF (see also the map in Figure A1, Appendix A). Most of these countries used both ERDF and ESF, while several used only ERDF (Austria, Czechia, Italy, Netherlands, Slovakia, and Slovenia) or ESF (Lithuania). Typically, the cohesion policy funds were delivered in combination with rural and/or fisheries funding.

Table 2.

Number of CLLD LAGs in the EU28 and their use of ESI Funds.

Servillo and Kah (2019) [6] analysed how different EU Members States have made use of CLLD under cohesion policy funds (ERDF and ESF) and proposed four types of countries, as follows:

- ◦

- No use—12 countries continued their 2007–2013 approach and decided to only make use of rural development and fisheries funding. Of these, the majority implemented CLLD in a traditional mono-fund way, namely Belgium, Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta, and Spain. Only Denmark and Latvia allowed multi-funding, combining EAFRD and EMFF in a limited number of LAGs.

- ◦

- Limited use--In five countries, cohesion policy-funded CLLD was implemented in a very limited way. This can be seen in Austria, Germany, and Italy, where the approach was only adopted by selected regions (Italy) or federal states (Austria, Germany). In the Netherlands, the application is even more concentrated, with just one ERDF-funded LAG in an urban area. In Lithuania, although applied across the country, the cohesion policy-funded LAGs only implemented the ESF without any multi-funding.

- ◦

- Extensive use—Six countries used CLLD more widely to implement cohesion policy funds. The UK left it to its devolved administrations to choose their approach, and only England decided to make use of both ERDF and ESF. Both Hungary and Romania expanded the range of funds used beyond rural development and fisheries by establishing CLLD LAGs in urban areas. However, these tended to operate separately from their EAFRD- and EMFF-funded counterparts. In Bulgaria, Greece, and two regions of Poland, a considerable number of LAGs added ERDF or ESF to the traditional funding sources, while established mono-EAFRD LAGs continued to play an important role.

- ◦

- Comprehensive use—The five countries that went furthest in their use of cohesion policy funds, with all allowing for multi-funding, were Czechia, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Sweden. In Czechia, Slovakia, and Slovenia, all LAGs used at least two funds. These three countries largely adopted a “one-size-fits-all” approach, with only minor differences in Czechia (not all LAGs used ESF) and Slovenia (four coastal LAGs also used EMFF). In Portugal and Sweden, however, there was a greater diversity of models. Eight LAGs in Sweden used all four available ESI funds; the only other case can be found in Poland (LAG Pojezierze Brodnickie).

It is interesting to compare the approach of two countries that made comprehensive use of CLLD. In Czechia, the largest amount of CLLD funding (EUR 437 million) came from the ERDF (representing the highest ERDF allocation to CLLD in the EU). Of the 178 multi-funded LAGs, 151 combined ERDF with EAFRD and ESF, while 27 used only ERDF and ESF. The ERDF was the lead fund, but the managing authorities were separate and the rules for each of these funds differed. In Slovenia, CLLD was developed based on the 37 LEADER LAGs from the 2007–2013 period. The EAFRD was the biggest source of funding, but all LAGs were also using ERDF, while the single coastal LAG and three inland LAGs with strong aquaculture were also using the EMFF. Although the EAFRD and EMFF were both managed by the Ministry of Agriculture and the ERDF by the government office in charge of cohesion policy, there was a joint selection procedure for all the three funds.

In contrast to Czechia and Slovenia, Sweden decided to implement a more bottom-up approach to the selection of ESI funds by CLLD LAGs. Most LAGs combined two or more ESI funds. Sweden decided to allow for as much integration as possible by creating a model in which there was one single managing authority for all four funds and where national implementation rules were harmonised. Sweden had 48 LAGs, each with a selection of funds tailored to their needs. Most (28) combined ERDF with both EAFRD and ESF, and 8 combined all 4 funds, while 6 remained mono-funded (either EAFRD or EMFF only).

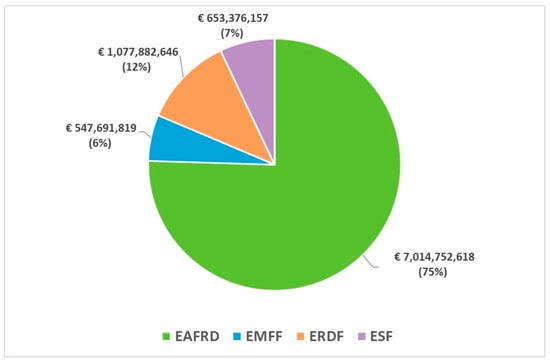

3.2. Funding for CLLD

Although one of the key innovations of the 2014–2020 programming period was widening the range of eligible funding sources for CLLD, only 16 Member States decided to allow the use of the structural funds ERDF and ESF. As the overview of funding sources (Figure 1) shows, LAGs continued to be predominantly funded by EU rural funds. In 2014–2020, the EU27 and the UK were implementing just under EUR 9.3 billion of ESI funding through CLLD. However, the vast majority—three quarters or EUR 7 billion—came from the EAFRD. Furthermore, it was often delivered in a traditional mono-fund way, continuing the long-established LEADER approach. The EMFF represented another 6% (EUR 548 million) of the whole CLLD funding, leaving only the remaining 19% to the two cohesion policy funds; the ERDF contributed 12% (EUR 1078 million) and the ESF 7% (EUR 653 million).

Figure 1.

EU sources of CLLD (LAGs budgets) [7].

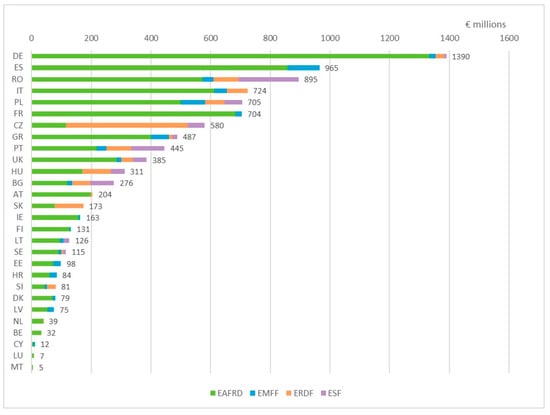

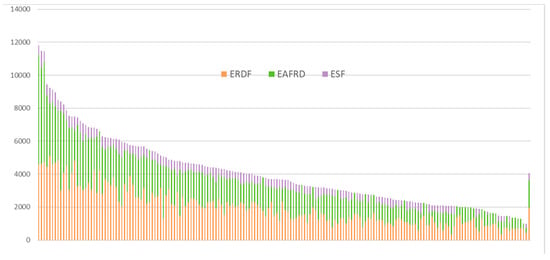

Most of those 16 Member States that made use of the option to add cohesion policy to the mix allowed this for both ERDF and ESF. However, in several countries (Austria, Italy, Netherlands, Slovakia, and Slovenia), LAGs could only make use of ERDF funding, while Lithuania decided to allow LAGs to use ESF funding, but not ERDF. Figure 2 shows how much each of the four ESI funds was contributing to the CLLD allocation in each country.

Figure 2.

CLLD allocation by ESI fund in each country (EUR) [7].

The country-level overview (Figure 2) confirms the dominance of rural funding for CLLD, as the EAFRD was the most important ESI fund in all but two Member States (Czechia and Slovakia). However, in some countries, the funding coming from structural funds—i.e., ERDF and/or ESF—was larger than rural and fisheries funding. This was the case in Czechia (80.1%), Slovakia (55%), and Bulgaria (50.4%), but the contribution of cohesion policy was also sizeable in Hungary (44.9%), Portugal (43.6%), and Slovenia (37.1%).

During the preparations for the 2021–2027 programming period, there have been claims, especially by rural actors, that the minimum compulsory allocation for CLLD (LEADER) in the case of the EAFRD should also be in place for the other eligible ESI funds. Proposals suggested that these minimum shares could, for instance, mirror those of the EAFRD, i.e., amounting to at least 5% of EMFF, ERDF, and ESF. The European LEADER Association for Rural Development (ELARD) even argued for a minimum of 15% from each of the four funds in its 2017 position paper on the future of CLLD/LEADER [8]. In light of these demands for not only more funding, but also for funding coming from a wider range of sources, it is useful to take a look at the role of different funds other than the rural one in the 2014–2020 programming period.

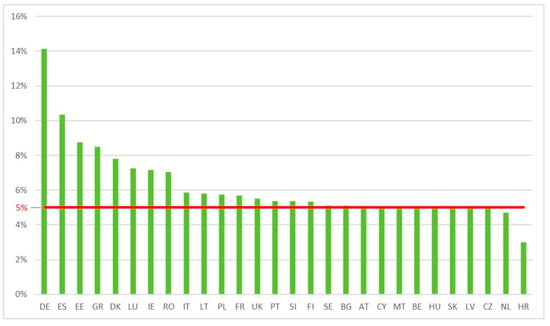

Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 illustrate the CLLD share for each of the three funds (EMFF, ERDF, and ESF). However, it has to be kept in mind that these shares might differ significantly in those countries with decentralised ESIF implementation. In some of those countries, one or only a few regional programmes were making use of cohesion policy funding for CLLD, while others did not. Examples of regional-level uptake of cohesion policy-funded CLLD include Austria (Tyrol), Germany (Saxony-Anhalt), Italy (Puglia, Sicily), and Poland (Kujawsko-Pomorskie, Podlaskie). Hence, apparently low shares of, for instance, ERDF in Poland and ESF in Germany, have to be interpreted against this background.

Figure 3.

Share of CLLD (LEADER) allocation of EAFRD by country, 2014–2020 [7]. Note—red line represents the minimum requirement of 5% of EAFRD funding for LEADER.

Figure 4.

Share of CLLD allocation of EMFF by country, 2014–2020 [7].

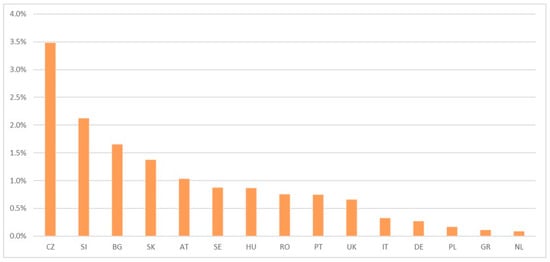

Figure 5.

Share of CLLD allocation of ERDF by country, 2014–2020 [7].

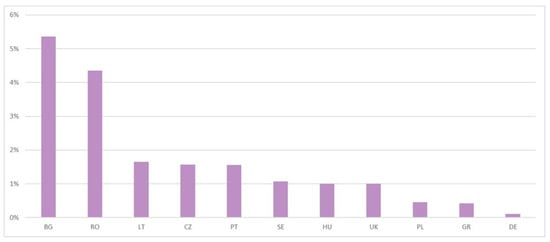

Figure 6.

Share of CLLD allocation of ESF by country, 2014–2020 [7].

The dominance of the EAFRD was mainly due to the obligatory minimum LEADER allocation of 5% (the only exception was Croatia, which entered the EU in 2013 and for which the obligatory minimum was set at 2.5%). Figure 3 shows that although the majority of countries did not go significantly beyond 5% of EAFRD, represented by the red line in the diagram, some opted to go well beyond these requirements. The highest shares of CLLD (LEADER) could be found in Germany (14.1%) and Spain (10.4%), which dedicated more than twice the required amount. Others, such as Estonia (8.7%), Greece (8.5%), or Denmark (7.8%), decided to allocate comparably high shares of their EAFRD envelopes to LEADER.

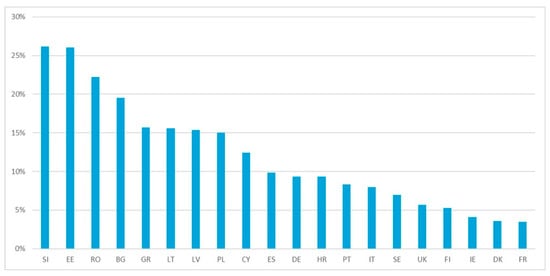

Compared to this, the shares of the fisheries fund, i.e., EMFF, were very high in some cases (Figure 4). Almost 10% of all its resources were dedicated to CLLD. However, the creation of Fisheries Local Action Groups (FLAGs) was not obligatory. Most of those 20 Member States that were funding (FLAGs) invested over 5% of their EMFF allocation, with two countries (Slovenia and Estonia), channelling over a quarter of it through CLLD.

Compared to the shares of EAFRD and EMFF, the use of cohesion policy funds—i.e., ERDF and ESF—for CLLD was relatively limited. This was the case not only in terms of the number of Member States using ERDF (15) and ESF (11), but also in terms of the share of these funds dedicated to CLLD. Overall, just 0.6% of ERDF and 0.8% of ESF funding went to CLLD. This is also illustrated in Figure 5 and Figure 6. The CLLD share of ERDF usually remained below 2%, with only Czechia (3.5%) and Slovenia (2.1%) going above this value. The CLLD shares of the ESF were not significantly higher, but two countries, Bulgaria (5.4%) and Romania (4.4%), stood out.

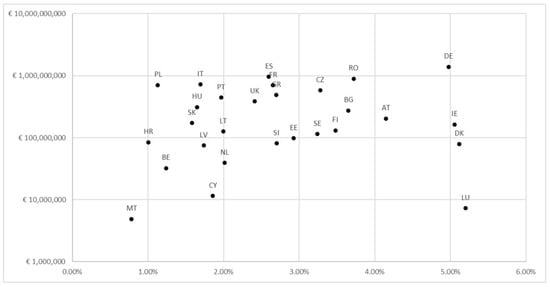

Moving beyond the individual funds, it is worth taking a look at the cumulative CLLD share of all four eligible ESI funds. Figure 7 shows a scatter plot presenting not only the CLLD share in percentages, but also the absolute available funding in Euros.

Figure 7.

Total CLLD funding (EUR) vs. CLLD share of eligible ESI funding by country, 2014–2020 [7]. Note—a logarithmic scale is used on the y-axis.

The overall share of CLLD by Member State was relatively evenly spread between 0.8% in Malta and 5.2% in Luxembourg. However, four countries stand out in terms of their CLLD share of funding; together with Luxembourg, Denmark (5.1%), Ireland (5.1%), and Germany (just under 5%) are also sitting at approximately the minimum allocation of 5% that was in place for the EAFRD and LEADER in 2014–2020. However, these figures are strongly skewed by the relative role of the EAFRD, which amounted to over 90% of all CLLD funding in those four countries. The over-representation of the EAFRD is particularly visible in the case of Germany, which also had the highest allocation to CLLD in absolute terms (EUR 1.39 billion), but this is mostly due to its very high share of LEADER funding (14.1%) shown in Figure 3.

This analysis of 2014–2020 allocation patterns to CLLD has shown a very diverse picture, but one that was still dominated by the only compulsory element of CLLD support, namely the 5% minimum allocation to LEADER. In the case of the EMFF, the shares were very high in several countries, but this had only a limited effect in absolute terms. Where these funds were used at all, CLLD shares in ERDF and ESF were usually low. Still, there were a few cases where they represented a sizeable share, such as the ERDF in Czechia or the ESF in Bulgaria.

Looking at the average amounts of funding available to each LAG provides another interesting perspective on EU-wide funding patterns. Across the EU, the average amount of funding available to a hypothetical LAG under the assumption of multi-funding was EUR 2.8 million. This average budget consisted of c. EUR 2.1 million of EAFRD, EUR 322,000 of ERDF, EUR 197,000 of ESF, and EUR 165,000 of EMFF funding. The smallest average budget could be found in Belgium with just EUR 1 million, which was also one of only three countries that exclusively financed CLLD from the EAFRD. The other two were Luxembourg and Malta, which were also among those countries with the lowest budgets. In the vast majority of countries, the average LAG budget sat between EUR 1 million and roughly EUR 3 million. Only a handful of countries went significantly beyond this, with Greece (EUR 9 million), Bulgaria (EUR 3.8 million), Germany (EUR 4 million), Ireland (EUR 4.5 million), and Portugal (EUR 4.8 million) showing the highest average budgets in the EU. The relative importance of funds other than the EAFRD could also be significant.

- The ESF played a very strong role for Portuguese, Bulgarian, and Romanian LAGs.

- The EMFF was particularly important in Cyprus, Estonia, and Latvia.

- The ERDF was a major source of funding in Slovakia, Slovenia, and especially in Czechia, where it was by far the dominant component of the average LAG budget. Interestingly, the corresponding average Czech EAFRD budget was the lowest in the whole of the EU.

However, as multi-funding arrangements varied widely throughout the EU and indeed within countries, averages had only limited significance. In Bulgaria and (some regions of) Germany, EAFRD, ERDF, and ESF could be combined, but there were separate strategies for EMFF; in Portugal there were multi-funded coastal FLAGs combining EMFF, ERDF, and ESF, and in non-coastal areas EAFRD, ERDF, and ESF could be combined; in the UK there could be strategies combining EAFRD and EMFF or combining ERDF and ESF. It should also be kept in mind that the possibility of multi-funding did not necessarily mean that all the LAGs (or FLAGs) of a given MS actually combined these funds in their strategies. In extreme cases, all four funds could be combined (e.g., Poland) or none (e.g., Romania).

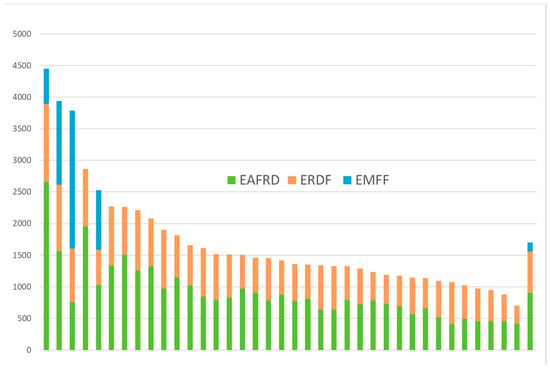

In order to illustrate the variations within countries, Figure 8 and Figure 9 provide examples of LAG budgets in Slovenia and Czechia, in both cases under conditions of multi-funding.

Figure 8.

Budgets of the 37 multi-funded LAGs in Slovenia 2014–2020, by ESI fund, in EUR 1000 [9]; Data from Slovenian programme authorities. Note—country average on the right.

Figure 9.

Budgets of the 178 multi-funded LAGs in Czechia 2014–2020, by ESI fund, in EUR 1000 [9] Data from Czech programme authorities. Note—country average on the right.

In Slovenia, the budgets ranged from just under EUR 4.5 million in one LAG to a handful of LAGs with less than EUR 1 million (the lowest budget was just over EUR 700,000). Most LAGs with very high budgets were also receiving EMFF funding in addition to EAFRD and ERDF sources. However, the vast majority of LAGs sat somewhere between EUR 1 million and EUR 2.5 million, with the average being EUR 1.7 million.

In Czechia, the smallest budget was EUR 982,000 and the largest was EUR 11.8 million, which is over 12 times as high. The average was EUR 4 million, which is more than twice that of Slovenia. The majority of Czech LAGs made use of three funds (ERDF, EAFRD, and ESF), but 27 LAGs did not receive any ESF funding.

Looking at the size of LAG budgets gives a better idea of financial CLLD resources on the ground than only using national figures. Still, research at the level of per capita funding would be needed in order to take the variable sizes of covered population into account. The currently available data is too heterogeneous to allow for an EU-wide overview without extensive research.

3.3. Experiences with CLLD Implementation

Experiences with CLLD implementation in 2014–20 have to be seen not only in light of the diverse range of potential funding sources and the resulting policy orientations, but also need to take into consideration widely different governance and implementation models. In some countries, LAGs acted as implementing bodies for higher-level actors, such as managing authorities or intermediate bodies, while in others they were able to take a much more bottom-up approach with more autonomy vis a vis the national or regional government levels.

The LDnet country profiles on CLLD implementation [10] allow us to examine some of the diverse experiences made with CLLD, looking at (a) the purpose of CLLD, (b) barriers in implementing CLLD, and (c) the achievements so far.

3.3.1. Purpose

Typically, purposes to which CLLD was put can be either process-focused or sector-or theme-focused. Examples of purpose-focused aims were innovation and knowledge exchange (Belgium-Flanders, Latvia), good governance and participation of stakeholders in the development of the territory (Bulgaria), and the promotion of public involvement in local economic development (Latvia). Sector- or theme-focused aims can be categorised as follows:

- Conventional approaches, e.g.,

- ◦

- Local development strategies (LDSs) focused mostly on entrepreneurship, small-scale food processing and production, artisanal entrepreneurs, thematic tourism and small-scale projects of public interest (Greece, under EAFRD).

- ◦

- Support focused mainly on investments to assist small-scale fishery and to add value to fisheries products, e.g., direct sales and short value chains (Italy, under EMFF).

- More nuanced formulations, e.g.,

- ◦

- The LDSs included local food pacts and short value chains, new services to the population, creation of “third places” (co-working spaces, fab labs etc.), etc. (France).

- ◦

- The LDSs included attracting young people and businesses to the rural areas, integration of migrants and refugees, a strong environmental focus, etc. (Sweden).

- In some cases, the formulation was in broad themes, e.g.,

- ◦

- Job creation and economic development, youth, reducing social exclusion and poverty (Lithuania).

- ◦

- Economic added value, natural and cultural heritage, common wellbeing (Austria).

- In a few (exceptional) cases there appeared to be no restrictions, e.g.,

- ◦

- Generally, LAG LDSs did not have any thematic or eligibility restrictions (Germany).

- ◦

- No thematic restrictions for LDSs (Luxembourg).

- The purpose tended to be differentiated according to rural, urban, or fisheries. For example, in Romania, the following occurred:

- ◦

- Under LEADER, key goals were fostering local initiatives, upholding local traditions, diversifying the local economy through investments in tourism, and adding value to local raw materials;

- ◦

- Under the EMFF, CLLD was mainly used to support investments in adding value to fishery products, diversifying local economies, and improvements in the infrastructures of fishery areas;

- ◦

- Under urban CLLD, the key aims were to reduce the number of people at risk of poverty and social exclusion in marginalised communities.

3.3.2. Barriers

Across the countries, barriers of heavy bureaucracy in the delivery process, administrative complexity and delays tended to be reported. The implications could discourage participation or innovation, as follows:

- ◦

- The main barriers were linked with the complex administrative systems and delays at the national or regional level. As a result, and also due to the lack of access to co-financing or pre-financing, many beneficiaries were unable or unwilling to apply for funding, or had to give up their project idea (France).

- ◦

- The administration of LEADER has become increasingly bureaucratic and burdensome. This can be off-putting for project promoters, and can lead to a decline in innovation (Ireland).

It can also mean that LAGs needed to play a facilitating role to help beneficiaries navigate the system, as follows:

- ◦

- The LAG and FLAG boards have been successful in hiring managers who function as brokers between applicants and the system, which in many other European countries is experienced as bureaucratic (Denmark).

- ◦

- Where national rules were excessively restrictive, LAGs had less time for animation activities and had problems motivating and explaining to local development stakeholders this top-down approach (Croatia).

- ◦

- There were also references to specific barriers, for instance at national level, as follows:

- ◦

- The centrally designed and imposed results-based monitoring system has been criticised as too complicated and somewhat missing the point of the LEADER added value (Austria).

- ◦

- Insufficient national promotion of the LEADER approach (Croatia).

- ◦

- There were also barriers at the local level, as follows:

- ◦

- The quality of the local partnerships—which is a key factor of success in CLLD—varied greatly (Italy).

- ◦

- Working with LAGs within different settings and with diverse levels of experiences was a complex challenge (Portugal).

However, while the origin of administrative complexities was often in the national implementation rules, the resulting extra burden was seen as an obstacle by all levels, including at the national/regional level (e.g., extra administrative effort for CLLD coordination and management in Germany) and the local level (e.g., the administrative burden proved to be challenging for LAGs in the Netherlands).

Multi-funding was particularly associated with extra complexity at both national and local levels, as follows:

- ◦

- Getting multi-funded CLLD off the ground proved quite challenging (Sweden).

- ◦

- The F/LAG management and strategy implementation had a high level of complexity due to the involvement of several uncoordinated managing authorities, several national or regional regulations, and many IT systems (Greece).

3.4. Achievements

In some Member States, achievements tended to be seen merely in terms of inputs, outputs, or results, such as project approvals, commitment of funds, and jobs supported/created (e.g., Greece and Portugal). In other cases, especially among older Member States, the main achievement was an established CLLD/LEADER approach, e.g., in Belgium (Flanders), where LEADER became an established element of regional and local rural development policies. The LAGs are well known and can build on experiences and networks gained in previous programming periods. However, sometimes this was seen mainly in terms of the achievements in mobilising the community and creating linkages between actors, e.g., in Greece, where the most important role of the F/LAGs in their area is animation and support. They acted as levers in local development and buffers to the heavy administrative work that has been noticed to increase enormously from one period to the other.

Sometimes, an all-encompassing perspective of CLLD embedded in institutional approaches and local communities was also highlighted. For instance, in Ireland, CLLD was strongly rooted in rural communities, and many public sector bodies have become progressively more inclusive of citizens and communities, and they consult more systematically with them in respect of the decisions that affect them. The capacity of civil society to devise and deliver projects has been strengthened, and many communities are embracing social economy approaches to local economic development. The valorisation of local resources and assets, associated with CLLD, is evident not just in rural development, but in the approaches pursued by statutory bodies, particularly in respect of tourism and food.

Specific achievements highlighted for some countries include the following:

- ◦

- The influence on equal opportunities in respect to gender was said to be tangible (Austria).

- ◦

- Self-evaluation has become common practice and yields satisfactory results (Austria).

- ◦

- The tackling of new themes, such as a circular and bioeconomy, alternative energy, smart villages, etc. (Latvia).

In some instances, the achievements focused on institutional or managerial innovations at national level, such as the following:

- ◦

- The one-stop-shop role of the CLLD Coordination Committee has proved to be a success, as it allowed for improving communication and capacity building between managing authorities, intermediate bodies, the paying agency, and LAGs (Slovenia).

- ◦

- A number of practical innovations have been introduced to facilitate CLLD delivery, such as umbrella projects, simplified cost options for running costs and for projects, or availability of advance payments for all types of beneficiaries—although there are some differences in the application of these mechanisms between funds. The special legal form established to facilitate the creation of LAGs as public–private partnerships was generally assessed as a success (Poland).

- ◦

- The first umbrella projects, for which simplified rules apply, were successfully implemented in the 2014–20 funding period (Luxembourg).

3.5. The Urban Dimension of CLLD

One of the key innovations of the 2014–2020 programming was opening up LEADER-type bottom-up development support, i.e., CLLD, to non-rural territories. Until then, towns were only eligible as part of wider rural territories, e.g., small county or district capitals. The new option of urban-focused LAGs was taken up in seven countries, namely Hungary, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, and the United Kingdom (England). In total, there were 223 urban LAGs, with most of them combining both ERDF and ESF (Table 3).

Table 3.

Urban CLLD LAGs in 2014–2020.

In contrast to rural or fisheries LAGs, urban LAGs always only involved a single municipality. Often, the targeted territory was a specific area in a city, e.g., in Lisbon (Portugal), The Hague (Netherlands), Timișoara (Romania), or Miskolc (Hungary). In other cases, often smaller towns, the entire territory of the municipality was targeted. This was the case in Lithuania and, typically, in Hungary and Romania.

It can be argued that there was a third type of urban CLLD, though still formally rural. In several countries, rural CLLD LAGs existed in peri-urban contexts. An example is Gothenburg, where the territory of the LAG Längs Göta Älv reaches into areas of urban character in the outskirt of Gothenburg. In Slovenia, all the country’s municipalities were covered by a LAG, including the major cities (e.g., Ljubljana, Maribor). In the cities, the targeted territories were classified as rural but sit within the city boundaries.

Urban LAGs addressed challenges that are often different from those in rural areas. In most cases, there was a combination of both ERDF and ESF that allowed covering classic urban themes. This can be illustrated by the example of urban LAGs in Romania, where the ERDF supported social housing, health and educational infrastructure and the upgrading of public spaces and utilities. On the other hand, the ESF funded education measures (e.g., reducing the number of early school leavers), accessing and remaining in employment (e.g., apprenticeships), integrated services (multi-functional centres, social services), and entrepreneurship both in the mainstream and social economy.

In many countries, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe, the introduction of urban CLLD provided a unique framework that did not yet exist in similar forms. The participating communities adopted a more strategic approach to local development, based on a multi-annual perspective and integrated investments that support common local strategic priorities. Urban CLLD created the framework and funding for community engagement, particularly in terms of support to reach disadvantaged groups, which so far have been excluded from similar policies (e.g., in Romania). It established stronger relationships and more effective coordination between municipalities, local communities, and programme managing authorities. It can be argued that the urban dimension of CLLD is the most visible innovation in EU-funded local development policy.

4. Discussion

The benefits of CLLD are usually attributed to its ability to strengthen local economies, build local capacity and enhance local governance [11]. The possibilities opened in 2014 of using CLLD under the different EU funds and—especially—combining them within a single strategy, allowed the LAGs to better respond to the needs of their areas and can lead to a number of positive effects, such as the following:

- Broadening the range of eligible themes, thus, strengthening the bottom-up decision-making;

- Targeting all types of territories, including rural, urban, and coastal areas;

- Increased synergies between policy areas;

- Economies of scale (for example for promotion and communication activities);

- Increased total funding allocation to the local strategies;

- Possibility of LAGs playing the role of “one-stop-shops” for different types of beneficiaries.

The experience of the 2014–2020 period shows that CLLD can be used in practice to involve a variety of local actors and to increase the integration of different policy streams. For example, multi-funded LAGs in Sweden had broader partnerships and were able to generate ideas from different fields of interest. In Tyrol (Austria), CLLD made it possible to integrate EAFRD and ERDF funding for the first time.

However, there remain many challenges. Instead of the policy content and the opportunities for rural or urban development, the discussion on CLLD often centred around the administrative complications and the associated risks. In fact, the administrative effort, including capacity challenges, for both programme managing authorities and LAGs, can be significant. Traditional silos are very difficult to break up. In most Member States it was not possible to combine different funding sources within a single project, so integrated activities required a combination of several projects, each with its separate funding source, indicators, and reporting requirements. Different sectoral actors tended to prefer maintaining control over “their” funding, instead of providing combined budgets to LAGs (and sharing the influence with other managing authorities). The need to coordinate the different implementation rules and procedures between managing authorities with different organisational cultures created long delays at the start in many Member States. Moreover, local initiatives were limited by what can be funded by the ESI funds, and national and regional authorities often added detailed eligibility rules on top of those at EU level.

It seems, therefore, that CLLD as a tool for policy integration has not yet been used to its full potential. Regulatory complexities also remain in 2021–2027, but there is the opportunity for one of the involved ESI funds to take on the role of “lead” fund, thereby following its specific implementation rules. Furthermore, there is a continued perception of CLLD as a rural tool (“LEADER with some extra money”), which results in limited interest by policy-makers in regional development and social policy fields.

The limitations of CLLD as implemented are also reflected in the report of the European Court of Auditors (ECA) on LEADER and CLLD [12] published in July 2022. Its title and message is that “LEADER and community-led local development facilitates local engagement but additional benefits still not sufficiently demonstrated”. However, the report is very much focused on the traditional LEADER model and gives less consideration to the opening up of the LEADER approach to other ESI funds, which is the key change between the 2007–13 and 2014–20 programming periods. The ECA touches on the related challenges and mixed experiences, albeit while remaining at the level of questioning the usefulness of mixing different funds. For instance, the report does not discuss the urban dimension of CLLD at all.

5. Conclusions

The CLLD seems now to have reached the status of a well-established policy instrument in different EU funds and different types of areas. The diversity of its application models makes it difficult, on the one hand, to draw general conclusions about its impact at the EU level, but—on the other hand—shows its extreme flexibility and adaptability to national, regional, and local contexts.

In the 2021–2027 programming period, CLLD will continue, albeit with some loss of regulatory integration of the various EU funding sources that can be used. Purely EAFRD-funded CLLD will continue to be referred to, as LEADER and the EAFRD are no longer covered by the Common Provisions Regulation (CPR) that governs the other funds eligible for CLLD, although the operation of LEADER LAGs is still governed by the CLLD rules set out in the CPR). For LEADER, the compulsory minimum allocation of 5% remains, but there is no compulsory CLLD allocation under other funds.

Some Member States are abandoning the cohesion policy-funded element of CLLD (Portugal, Slovakia, and Sweden). The reasons for this are diverse and not always purely related to experiences of inefficient implementation. Others will continue existing models (e.g., Austria, Czechia, and Germany), some will expand the use of CLLD (e.g., Lithuania, the Netherlands, and Poland), and Estonian LAGs will start using ESF funding in addition to rural and fisheries funding. At the time of writing (December 2022), it was not possible to present a comprehensive overview of CLLD uptake.

As one of the most innovative elements, urban CLLD will also continue, and it will be expanded to more LAGs, in, at least, Lithuania, the Netherlands, and Romania. A new element is that funding allocated to urban CLLD will count into the mandatory ERDF earmarking of at least 8% to sustainable urban development. Although CLLD budgets tend to be comparatively small, adding CLLD as one possible framework to fulfil the regulatory requirement could encourage its uptake in urban areas.

Administrative effort and perceived delays to funding absorption remain crucial concerns for programme managers, resulting in a cautious attitude to the use of CLLD. Instead of multi-funding, which is often considered challenging, focusing on mono-fund models—beyond EAFRD and EMFF—could provide a way forward. This is something that is a common approach in urban LAGs, which are sometimes mono-funded by ERDF (Netherlands) or ESF (Lithuania, Poland).

One of the main ways to avoid a (further) delay in starting the 2021–2027 programming period is to ensure continuity and limit change. Programme managing authorities as well LAGs can build on the experiences made in 2014–2020. For instance, LAG managers can work with established local stakeholder networks, and LDSs can be updated instead of being written from scratch.

For those starting a CLLD model beyond LEADER and fisheries, learning from the experience of others should be encouraged. This can be carried out nationally but also internationally. However, the available frameworks for the exchange of experiences are targeted either towards rural (LEADER) actors, via the former European Network for Rural Development (now rebranded as EU CAP Network), or towards fisheries actors, via the former FARNET (now rebranded FAMENET). Those LAGs that do not (also) make use of either rural or fisheries funding risk a “fall through the cracks”, as there is no similar knowledge exchange and support offer. As most of these purely cohesion policy-funded LAGs are urban, the newly launched European Urban Initiative might be a suitable framework to close this gap.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K. 40%, H.M. 30% and U.B.-T. 30%; methodology, S.K. 40%, H.M. 30% and U.B.-T. 30%; formal analysis, S.K. 20%, H.M. 60% and U.B.-T. 20%; writing—original draft preparation, S.K. 70% and H.M. 30%; writing—review and editing, S.K. 40%, H.M. 30% and U.B.-T. 30%. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Large parts of the findings presented in this article have been developed in the context of LDnet activities, including CLLD country fiches. However, the analysis and conclusions in this article are the sole responsibility of the authors, who would like to thank the following contributors who have prepared country material for LDnet: Robert Lukesch and Michael Fischer (Austria), Wouter Peeters and Nicolas De Fotso Tchienegnom (Belgium), Neli Kadieva (Bulgaria), Bojana Markotić Krstinić (Croatia), Ondřej Konečný (Czechia), Annette Aagaard Thuesen (Denmark), Triin Kallas (Estonia), Marjo Tolvanen (Finland), Yves Champetier (France), Stefan Kah, Niko Wagner, Alistair Adam Hernández, and Pedro Brosei (Germany), Iro Tsimpri and Tasos Perimenis (Greece), Brendan O’Keefe (Ireland), Rosalba La Grotteria, Carlo Ricci and Franco Mantino (Italy), Anita Seļicka (Latvia), Ilona Javičienė (Lithuania), Françoise Bonert (Luxembourg), Philip Emmanuel Vella (Malta), Thamar Kok and Josh Geuze (Netherlands), Urszula Budzich-Tabor and Joanna Gierulska (Poland), Pedro Brosei, Luis Chaves and Maria Joao Rauch (Portugal), Catalin Tiuch and Alexandru Brad (Romania), Alina Cunk Perklič, Aleš Zidar, and Stefan Kah (Slovenia), and Urszula Budzich-Tabor (Sweden). The country profiles are published on the LDnet website at https://ldnet.eu/category/resources/clld-country-profile/ (accessed on 11 January 2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Map of cohesion policy-funded CLLD LAGs in 2014–20 [13].

References

- European Network for Rural Development (ENRD). LEADER Historical Resources. Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/leader-clld/leader-resources/leader-historical-resources_en (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- Copus, A.; Dax, T. Conceptual Background and Priorities of European Rural Development Policy. Assessing the Impact of Rural Development Policies (Incl. LEADER). RuDI 2010, 44. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/18418854/Assessing_the_impact_of_rural_development_policies_incl_LEADER_Conceptual_Background_and_Priorities_of_European_Rural_Development_Policy (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- Dargan, L.; Shucksmith, M. Leader and Innovation. Sociol. Rural. 2008, 48, 274–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukesch, R. Leader Case Study. Social Innovation—Implicit to the Leader Approach. European Network for Rural Development. 2020. Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/enrd_publications/s12_leader_case_study-at_social-innovation.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- Servillo, L. Tailored polities in the shadow of the state’s hierarchy. The CLLD implementation and a future research agenda. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 678–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servillo, L.; Kah, S. Implementing CLLD in EU: Experiences so Far. In Proceedings of the ELARD Conference 2019, Amarante, Portugal, 25–26 November 2019; Available online: https://leaderconference2019.minhaterra.pt/rwst/files/I119-CLLDX231219XSERVILLOXKAH.PDF (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- ESI Funds Open Data Platform. Available online: https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/ (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- European LEADER Association for Rural Development. Position of European LEADER Association for Rural Development. Renewing LEADER/CLLD for 2021–2027 Programming Period. In Proceedings of the ELARD General Assembly Meeting, Laulasmaa Spa, Estonia, 22–24 November 2017; Available online: https://media.voog.com/0000/0041/5573/files/ELARD_position-LEADER_CLLD_2021-2027.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- CLLD Comparisons: ESI Funding Available to LAGs in Different Countries. Available online: https://ldnet.eu/clld-comparisons-esi-funding-available-to-lags-in-different-countries/ (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- The European Local Development Network (LDnet) Aimed to Present in a Systematic and Succinct Way How CLLD is Implemented in Different EU Member States. With the Support of Policy-Makers and Researchers in the Different Counties, LDnet Prepared 23 Country Profiles between June 2020 and May 2022. Available online: https://ldnet.eu/category/resources/clld-country-profile/ (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- Dwyer, J.C.; Kubinakova, K.; Powell, J.R.; Micha, E.; Dunwoodie-Stirton, F.; Beck, M.; Gruev, K.; Ghysen, A.; Schuh, B.; Münch, A.; et al. European Commission, Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development. In Evaluation Support Study on the Impact of Leader on Balanced Territorial Development: Final Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/bd6e4f7c-a5a6-11ec-83e1-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- European Court of Auditors. Special Report 10/2022: LEADER and Community-Led Local Development Facilitates Local Engagement but Additional Benefits Still not Sufficiently Demonstrated, Brussels, Belgium. 2022. Available online: https://www.eca.europa.eu/en/Pages/DocItem.aspx?did=61355 (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- European Commission Joint Research Centre Database STRAT-Board. Available online: https://urban.jrc.ec.europa.eu/strat-board/#/where (accessed on 11 January 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).