Abstract

In this paper, we explore the idea of social innovation as both a conceptual and practical means of delivering positive social, economic and environmental outcomes in marginal rural areas. Definitions are critically appraised, and the dual contemporary origins of the term social innovation (in management sciences and critical social science) are explored. There has been much conceptual confusion, in particular about the extent to which civil society agency is central or desirable in social innovation. Social innovation can be seen to be closely connected to a range of theories that inform both innovation and rural development, but it lacks a singular theoretical “home”. Social innovation can also have a dark side, which merits scrutiny. Three case studies illustrate social innovation processes and outcomes in different parts of Europe. Where committed actors, local enabling agency and overarching policies align, the outcomes of social innovations can be considerable. If rarely transformational, social innovation has shown itself capable of delivering positive socioeconomic and environmental outcomes in more bounded spatial settings. It seems questionable whether social innovation will survive as an organising and capacity-building concept alongside more established principles, such as community-led local development, which, although not exactly social innovation, is very similar and already firmly embedded in policy guidance or whether it will be replaced by new equally fuzzy ideas, such as the smart village approach.

1. Introduction

Over the last decade, the idea of social innovation has been used to help throw light on complex processes of socioeconomic and spatial restructuring that have emerged at multiple levels in developed Western economies, especially as responses to the challenges confronting marginalised rural areas [1]. Social innovation has been articulated as a potential mechanism to advance sustainable development outcomes [2]; some even conceive of it as capable of ushering in potentially transformative changes towards sustainability [3], whereas others see it as capable of delivering more locally based outcomes in response to failure in the delivery of basic services by the state or markets [4]. In all cases, social innovation refers to a process of transformation of social practices (i.e., attitudes, behaviours and networks of collaboration) that usually includes the engagement of civil society actors [5].

The trigger for social innovation is normally some kind of stress, weakness or crisis in prevailing socioeconomic structures and/or at a policy level. Crises happen at multiple spatial and temporal scales: at the global level as a result of the financial crisis after 2008 or the existential crisis caused by anthropogenic climate change; at regional or more local level, crises can result from the adverse effects of individual extreme events, such as floods or fires; at the microlevel, the trigger can be adverse socioeconomic events, such as the closure of the only remaining village shop, post office or school. Alternatively, social innovation can respond to incremental social, economic or environmental change that has severely compromised a region or community’s prosperity and well-being. For its capacity to improve the well-being of rural communities and societies and support the transition toward sustainability, social innovation has also been promoted by policy makers at regional, national and transnational levels to simultaneously create social, economic and environmental benefits. However, it has rarely been named in specific policy instruments and never allocated specific resources in EU rural development programmes.

Even if some practical activity in the field of social innovation preceded it, the principal trigger inducing public policy engagement in Europe was the global financial crisis that began in 2008. The faith of the public and public institutions in the market was challenged by the major volatilities of the financial system, which led to critical scrutiny of the prevailing neoliberal orthodoxy. Social innovation was envisaged as a means by which civil society actors could begin to nurture a more socially benign mixed economic model, either by civil society alone or in association with national and local government actors, to help address the needs of the major casualties of the financial crisis. Arguably, a second narrative of empowering disadvantaged groups had already firmly established itself in marginalised places (more cities than rural areas) [6] before the financial crisis hit. Indeed, it can also be argued that the social innovation narrative, as a way of meeting grand societal challenges, was also already influential in some countries where “third-way” politics prevailed, multilevel governance was in place and partnership approaches were widely used.

At the EU level, the European Commission took a great interest in social innovation after the 2008–2009 economic crisis. Commission President Barroso argued in 2010 that “the financial and economic crisis makes creativity and innovation in general and social innovation in particular even more important to foster sustainable growth, secure jobs and boost competitiveness” [7]. The term social innovation may be less used today but still appears at the European level in the EaSI programme (EaSI = Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, a strand of the European Social Fund Plus in the budget period 2021–2027; (see the website of the European Commission [8]) which “provides financial support to achieve high employment levels, fair social protection, a skilled and resilient workforce ready for the future world of work, as well as inclusive and cohesive societies aiming to eradicate poverty” [9]. comfortably within the original Barroso narrative. Furthermore, the term retains contemporary salience in relation to renewable energy and the energy transition in EU policy [10].

This paper is structured to address the following research questions: (1) Is there a coherent conception of social innovation that feeds into the policy environment, and if so, what are its theoretical underpinnings? (2) Does it matter that there are such diverse framings? (3) How has European policy towards social innovation evolved? (4) Can an exploration of cases of social innovation yield insights as to when social innovation might deliver promising outcomes? We then (5) explore whether there is a “dark side” of social innovation and, finally (6), discuss whether there is anything distinctive about social innovation set against the plethora of related concepts, including CLLD and coproduction.

To answer the research questions, we start from a critical discussion of the social innovation concept and its policy development in the EU context and then explore the theoretical roots of social innovation. We use the empirical content of three social innovation initiatives to show that in each context, social innovation supports CLLD by producing social, economic and environmental outcomes. The Austrian case focuses on socioeconomic aspects and outcomes through innovative approaches to career orientation, bringing local entrepreneurs and school leavers together in unusual and inclusive settings; the Italian initiative focuses on social care delivery but also has clear economic outcomes; and the Scottish project focusses on environmental outcomes but also has strong social and economic components.

The reflections in the paper grew out of the authors’ deep involvement in the Social Innovation and Marginal Rural Areas (SIMRA) project, an EU Horizon 2020 research project that ran from 2016 to 2020. The opinions expressed are those of the authors alone and do not represent those of the project team as a whole. However, they could not have evolved without the extensive dialogue both with the project team and many others and are influenced by the variety of case studies undertaken in the SIMRA project, examples of which we draw on below.

2. Definitions, Conceptual Approaches and Theoretical Framings for Social Innovation

The most commonly used definition of social innovation asserts that “social innovations are innovations that are social in both their ends and their means…we define social innovations as new ideas (products, services and models) that simultaneously meet social needs (more effectively than alternatives) and create new social relationships or collaborations. They are innovations that are not only good for society but also enhance society’s capacity to act” [11]. A more recent comprehensive definition suggests that “social innovations comprise new ways of doing (practices, technologies, material commitments), organizing (rules, decision-making, modes of governance), framing (meaning, visions, imaginaries, discursive commitments) and knowing (cognitive resources, competence, learning, appraisal)” [3].

Many authors have alluded to conceptual and definitional confusion [12,13,14]. It might be argued that social innovation’s conceptual and definitional fluidity weakens its usefulness as an organising concept. Because it has been approached from so many disciplinary (and some interdisciplinary) perspectives, it tends to carry with it the theoretical baggage from different disciplines, which range from geography to sociology to science and technology studies (STS) to management and policy sciences. Many of the definitions are imbued with normative elements, which vary from definition to definition. Somewhat surprisingly, ideas about social innovation are only weakly connected to innovation theory and receive only cursory treatment in the OECD’s Oslo manual [15].

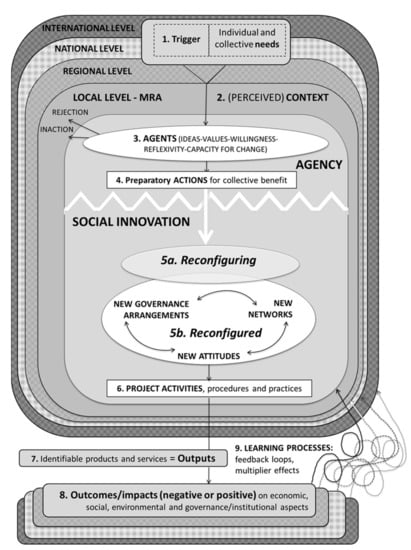

Our general exploratory framing within the SIMRA project was built on Giddensian structuration perspective. The interactions of agents and structures create and reproduce social systems at multiple scales. Where there are tensions and crises in social systems, alternatives are explored both though practical actions and by the evolution and modification of prevailing institutions and structures. Figure 1 describes the context within which social innovation arises. Stresses (or, on occasion, new opportunities) in prevailing socioecological systems are shaped by combinations of causal factors from the international to local scale. These stresses/opportunities set in motion a series of preparatory activities, which may lead to new institutional formation and new practices. Reconfiguration of existing institutions and processes is at the heart of social innovation. This process of reconfiguration has also been described as institutional bricolage, [16]—a locally adapted set of institutional and agentic responses to emergent stressors in socio-ecological systems (as shown at stage 5 in Figure 1). Social innovation comprises the reconfiguration of institutions and processes in response to stresses in a socioecological system in which civil society agency occupies a prominent, if variable, role.

Figure 1.

Social Innovation: a conceptual model. Source: [17].

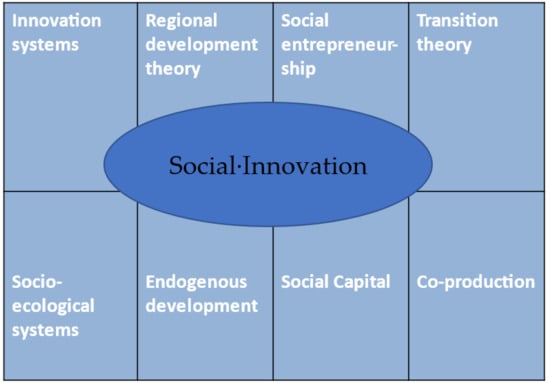

Within the SIMRA project, social innovation was used as a lens to explore the diverse actions associated with bottom-up rural development. Many attempts have been made to connect to possible theoretical roots of social innovation. We identify eight theoretical perspectives that might offer insights into social innovation in the context of community-based rural development. There are some partial overlaps but, we argue, sufficient difference for them to be viewed separately. They are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Theories offering insights into social innovation. Source: authors’ own work.

2.1. Innovation System Theory

Given that social innovation is part of a wider set of innovative behaviours, one might expect theories of innovation to inform thinking about social innovation. Two types of innovation theory might be seen as relevant. First, it is argued that innovation does not normally happen serendipitously. It is normally triggered by a resource shortage, a cost price squeeze or a failure in established modes of provision of a good or service. How and under what circumstances innovation occurs has been widely explored through the lens of innovation systems. Edqvist [18] sees the innovation system as the sum of all the institutions working collectively to promote innovation. Innovation systems can be sectoral or relate to nations or regions. Social innovations can be seen as part of restructuring processes and the output of an innovation system, most likely one where more technical alternative solutions alone had been found wanting. The European Commission has strongly endorsed the idea of innovation systems or ‘ecosystems’ in the European Innovation Partnerships but, in a rural context, has struggled somewhat to give them a territorial rather than a sectoral focus. Granstrand and Holgersson [19] define innovation ecosystems as “the evolving set of actors, activities, and artifacts, and the institutions and relations, including complementary and substitute relations, that are important for the innovative performance of an actor or a population of actors”.

The second body of innovation theory relates to the diffusion of innovations [20]. Rogers considers the propensity to adopt innovations to be a function of both the nature of the innovation and the socioeconomic characteristics of the adopter. His ideas may have particular relevance in explaining what is often described as scaling up or scaling out of social innovations or, more simply, their diffusion.

2.2. Socioecological System Theory

The ideas of a socioecological system (SES), resilience and adaptive capacity have been developed by Folke and others [21]. Human–environment systems are complex and may be more or less resilient and more or less able to adapt. While most obviously relevant to rural land management systems or ecological management of protected areas, such models may well have wider applicability both to rural development and even urban applications. Elinor Ostrom [22] connected her institutional analysis and development ideas to the SES framing and developed a framework for analysing complex socio-ecological systems. In particular, with others, she counselled against the presumption that downloaded blueprint solutions will work in different time and space contexts [23]. Her approach focuses on understanding local institutional and resource contexts and their adaptive capacity. In the face of the complex resource management problems of common pool resources, she makes a strong case for collaborative management within what she terms a polycentric governance framework as an effective resource management approach. This body of knowledge engages in concepts closely connected to social innovation.

2.3. Regional and Endogenous Development

There is no single theory of regional development, but a strong body of work from Myrdal [24] onwards argues that spatial unevenness in development is inevitable under capitalism and that peripheries from metropolitan cores often face compound disadvantages as capital and talent leak out and demographic decline often ensues. Public intervention is widely regarded as necessary to break the downward spiral and early public policies focussed variously on branch plant developments and infrastructure provision with limited success. This has led to various attempts to connect development strategies more closely to local capacities and resources.

Perhaps the dominant theoretical framing for marginalised rural areas is endogenous development theory [25] and its associated neo-endogenous development theory [26]. Van der Ploeg has been highly critical of attempts to shoehorn development into a unilinear model, arguing instead that endogenous (or, in developing countries, indigenous) knowledge platforms create opportunities for sustainable rural development not based on diffusion of core technologies. It is highly likely that such endogenous knowledge, especially in relation to local food systems, is more important where core technologies and innovation systems are least able to offer viable alternatives to the status quo. These concepts articulate into the more encompassing regional development approaches marshalled by the OECD [27,28] and framed as place-based approaches by the EU [29].

2.4. Social Entrepreneurship

In areas where markets are weakest, it is likely that alternative models of provision of goods and services may be more important. Such areas may well be rural peripheries or deindustrialising communities. In these places and amongst those most disadvantaged, there may be greater reliance on household provision of services and on collaboration and collective action—what Raymond Williams [30] described as the “mutuality of the oppressed”. The forms of collaboration may be formal or informal, but communal management of common pool resources may linger longest where there is less motivation to assert private property rights. The most common form of collective enterprise is the cooperative. Cooperative action has extended from its origins in food provision, farming, insurance and banking into new areas, such as watershed management and environmental goods and services [31] and social care [32]. Furthermore, different forms of social enterprise may take on key functions as markets or the state withdraw through lack of return or paucity of resources. Public policy may support cooperative action and social enterprise [33]. Furthermore, new models of collective ownership, such as community ownership of land [34] may emerge.

2.5. Social Capital

Social and political scientists have been aware for some time that the nature and composition of social capital are important factors in local development. While Putnam and others [35] has emphasised trust as a key ingredient in social capital, others, such as Coleman [36], have stressed the importance of networks. Different types of social capital have been identified, and particular importance is given to the distinction between bonding social capital, where there are shared values, and bridging or linking social capital, where local actors are connected to other networks, which may be especially important when the bridging is to gatekeepers to funding. Recently, Muringani et al. [37] published econometric analysis that reaffirms the greater importance of bridging capital rather than bonding capital in shaping economic development outcomes.

2.6. Transition Theories

The bringing together of ideas of social innovation and transition management has been championed by Haxeltine, Avelino, Pel and others [38,39]. Transition management theory has its roots in science and technology studies and adopts what it terms the multilevel perspective, in which niche alternatives develop in response to challenges confronted by the dominant regime and which, under propitious circumstances, can be upscaled to effect regime and landscape changes [40]. In its earliest manifestations, these niche developments related mainly to technical innovations, but niches may also relate to social innovation.

Within a transition-theory perspective, social innovation is seen to comprise a means of supporting “radical transformation towards a sustainable society, as a response to a number of persistent problems confronting contemporary modern societies” [41]. Shove and Walker [42] make some potent criticisms of transition theory. In particular, they argue that “there is a politics to transition management, a playing out of power of when and how to decide and when and how to intervene, which cannot be hidden beneath the temporary illusion of ‘post-political’ common interest claims of sustainability”. They also argue about the inability to be certain of system dynamics and the capacity of systemic changes to generate unforeseen effects. The general neglect of the power relationships involved in social innovation may reflect avoidance of its historic identity as an emancipatory force [43] in an effort to make it more politically palatable. Wright [44] describes the lower likelihood of what he describes as ruptural transformations and the greater likelihood of interstitial or symbiotic change. The work of Avelino and others [45] (rightly, in our view) renews the emphasis on power relations, which have all too often remained hidden in the field of social innovation but may overemphasise the importance and likelihood of transformational change. Shucksmith [46] also addresses issues of power, noting the decline in the state’s capacity to govern remote marginalised areas, where withdrawal of public services can seem like an abdication of public responsibility, but at the same time offers an opportunity for exploration of alternative models of community-centred provision.

2.7. Coproduction

The final framing of social innovation is in relation to the idea of coproduction [47]. In its earliest use, society and technology were seen as mutually constitutive; however, in later use, the term has acquired additional elements associated with multiagency activity in pursuit of sustainability enhancement. Particularly in relation to biodiversity and ecological challenges, coproduction is increasingly seen as a lens through which creative solutions can be explored [48,49]. In such contexts, coproduction is almost a synonym for social innovation.

2.8. Cross-Cutting Perspectives

The described framings and theoretical positions are neither wholly comprehensive nor entirely distinct. A sociological framing rooted in structure agency ideas is used by Cajaiba Santana [50] which, in some ways, constitutes a cross-cutting perspective similar to that adopted in the SIMRA project. A further cross-cutting perspective emerges from the political sciences built around a narrative on multilevel governance and the “hollowing out” of the nation state [51]. This hollowing out is characterised by the emergence of globalisation alongside new forms of local and regional governance. The withdrawal of the state leaves vacant niches, which social institutions may evolve to fill (see also Wright’s interstitial change) [46]. These local-level interactions between agency and structure have been described by Cleaver [16] as “institutional bricolage” in which social innovation can be seen as an important driving force.

In terms of connecting different theoretical perspectives, Foxon [52] have argued for connecting transition theory, adaptive management and socioecological systems analysis as an exploratory lens. Transition management also has close connections with science and technology studies (STS), which connect to ideas of coproduction. Recent work from Wageningen has partially reframed endogenous development theory in a transition management framework.

It is suggested that there are two broad schools of thought centred on social innovation [13]: one seeing social innovation as part of the contestation around existing power relations and having the potential to challenge extant power relations by the formation of new institutional forms [53,54] and the other taking a more utilitarian management sciences perspective and trying to address prevailing social problems (often framed as grand societal challenges or wicked problems), most strongly articulated in the work of Mulgan [55,56]. Whereas the latter approach voices no need for theoretical refinement of the concept, the former and many others have been much more concerned about identifying a robust theoretical positioning. These two approaches, one rooted in business school managerial concepts (for example, “design thinking” from US Business schools has been incorporated into social innovation processes; and the expansion spiral for social innovation is lifted from Ernst & Young management consultancy thinking) and the other in critical social science, can make uneasy bedfellows.

The next section explores the practical and policy consequences of this diverse bundle of theories.

3. Does the Divergence of These Concepts, Framings and Theories Matter?

Implicit in all the theoretical positions is that social innovation occurs as a change in the way groups of people think, interact and act, potentially in association with technology in response to a situation of stress, perturbation or opportunity in a system. Both policy makers and practitioners seek improved solutions to the extant unsatisfactory state. Both are struggling to develop a consistent theoretical framing.

Neither of the definitions of social innovation used above explicitly and unambiguously identifies the agency involved in social innovation. The driving agency may be state, municipality, NGO or informal citizen group. In the wider narrative surrounding social innovation, the term empowerment is often used, which implicates civil society actors. Although third-sector actors predominate in most examples of social innovation, many references suggest that public policies and practices at national, regional and municipal level also comprise social innovation.

The fact that social innovation connects to so many different theoretical perspectives suggests a fluid concept given multiple meanings by different scholars and actors at different times and that addresses different contexts. Further, it was evident in fieldwork associated with the SIMRA project that many actors on the ground who might be described as social innovators had no conception of themselves as such. Social innovation is a conception rooted in the policy community, with different parts of the science community seeking to give it theoretical framing but remains largely ignored by the lay community. Whether such a malleable and multiple-rooted conception can evolve into a coherent conception of something distinct from other theoretical perspectives on innovative community-led local development remains a matter for debate.

Theoretical contestation can be seen either as a sign of robust exploration of a novel phenomenon or as a sign of confusion. It is not helped by a lack of clarity over the definitions. What is incontestable is that social innovation has assumed greater prominence both in narratives of local development and in more global narratives addressing problem solving of long-standing wicked problems. The breadth of scale at which social innovation is seen to operate is diverse, and the associated rationales are very different. With such fluid concepts and varied theoretical foundations, social innovation may be a fragile base on which to construct a policy architecture to drive positive outcomes. It is challenging to even design intervention logic or a theory of change to influence something so loosely defined and so variably framed by such diverse theories. Nonetheless, the European Union has engaged, at times wholeheartedly, with the concept.

4. How has the European Policy Community Framed Social Innovation?

Since President Barroso’s statement in 2010, the European research and policy narrative has evolved somewhat. By 2018, Carlos Moedas, the then Commissioner for R&D, argued that “social innovation is about using innovation to tackle societal challenges such as climate change or migration, and—crucially—doing it in a way that actively involves the people who will be affected” [57]. The researchers and practitioners who framed the Lisbon Declaration on Social Innovation identified the following priorities:

- Making funding suitable for small-scale experimentation, spreading and scaling impact;

- Enabling citizens and civil society to lead local change initiatives through community-led innovation;

- Strengthening the capacity, skills and incentives for public officials and policymakers to support and draw on (citizen-led) social innovation;

- Making public procurement an instrument of social innovation policy; and

- Prioritising the spreading of social innovation to regions where it is needed most.

This narrative is firmly rooted in a state-assisted citizen empowerment and partnership narrative, which has assumed even greater importance in the light of populism and anti-European Union sentiments. This local empowerment narrative already had salience in the idea of community-led local development (CLLD), and the Commission is clearly motivated to promote community-led local development to drive more diverse and locally adapted forms of policy engagement with local communities.

A further narrative surrounds the long-standing concern with uneven spatial development across Europe, most clearly evidenced in the operation of the Structural Funds. The uneven development of advanced industrial capitalism is potentially politically destabilising. Lagging regions are seen as meriting policy support for reasons of equity but also to increase economic efficiency, and policies have evolved to favour CLLD. In the most lagging regions, community enterprise is seen to fulfil an important role.

Alongside articulations of social innovation in the EaSI strand of the ESF+ (European Social Fund Plus (2021–2027)) and in relation to renewable energy, it is also closely connected with the Commission’s wider recognition of community-led local development (CLLD) and in smart villages thinking [58]. Most but not all narratives of smart villages embody ideas closely connected to social innovation but often focus more explicitly on place-based business entrepreneurship. Climate change and renewable energy policy is also now seen as an important arena where social innovation can apparently make a difference. However, in the latest long-term European Commission rural strategy, the Long Term Vision for Rural Areas [59], no reference at all is made to social innovation, although the term appears several times in the supporting documents.

Following the rhetorical flourishes from senior EU politicians on social innovation, the European Commission has funded a significant number of projects through the Framework 7 and Horizon 2020 programmes. A research call in 2013 was linked to “an increasing interest in the ways that social innovation could contribute to solutions to many of the problems associated with government budget cuts, stagnating economies, high unemployment, and other pressing social needs and environmental concerns”. The TRANSIT project was the first major research project in response to this call, and several more followed, including SONNET and SIMRA in Horizon 2020.

LEADER is the principal policy instrument implementing CLLD in rural areas. Initially, LEADER had a genuinely radical flavour, challenging municipal, regional and central government by the creation of free-standing partnerships. In its earliest phase, LEADER was limited to disadvantaged and severely disadvantaged areas, which were formulaically defined at the EU level as Objective 1 and Objective 5b areas. The policy narrative implied a need for a radical alternative to the large-scale capital injections of some of the early European policy interventions in remoter rural regions. Individual evaluations of LEADER projects in the early years showed very promising results [60]. The European ex post evaluation of LEADER I [61] essentially contributed to defining the LEADER method, a necessary prerequisite for the scaling up and institutionalisation at the member-state level in the following funding periods. Subsequently, LEADER and the evolving principles of CLLD were rolled out across all rural areas, suggesting that CLLD was not simply a means of compensating for market failure in disadvantaged regions but also had salience in more developed areas.

LEADER has long appealed to a particular constituency of local development activists because it partially decentralises power to partnerships, but it remains vulnerable to capture by local elites and has been viewed somewhat critically by the European Court of Auditors [62] and Dax et al. [63]. The extent of empowerment may be limited, and Avelino et al. (2019) suggest that in spite of the rhetoric to the contrary, such empowerment may be illusory. As LEADER has evolved in certain member states, at least in distinct implementation periods, it has been drawn more closely under the control of municipal or sectoral interests and may have lost some of its early vitality due to excessive red tape. It is seen as in need of rebooting [64,65]. Surprisingly, social innovation narratives have made little headway into LEADER thinking and practice, although there can be little doubt that a very significant proportion of LEADER-funded projects could unproblematically be rebadged as social innovation.

As place-based community development assumes a stronger position in rural development discourse, the scale at which policy interventions are best framed requires consideration. Do LEADER local action groups representing areas with over 100,000 people spread over huge, sometimes lightly populated areas with large internal variations in local well-being constitute meaningful entities in which CLLD can flourish? Are bounded local communities or areas much smaller than those covered by a single LEADER local action group a more appropriate spatial scale for CLLD and social innovation?

The latest “soundbite” policy to influence rural development at the EU level and which connects closely to social innovation is the idea of smart villages. The concept has often been framed only in the context of better IT connectivity and better use of IT, although ENRD workshops have stressed the role of social capital, as well as connectivity and IT skills. Building on the recognition that some communities appear to outperform expectations in terms of their ability to retain or grow their population, adopt innovative practices and draw down social and economic development opportunities, smart villages policy has emerged to try to replicate the diverse forms of good practice evidenced in successful communities. As with social innovation, a similar lack of a strong theoretical framing prevails, and scope for replication of successes in unsmart places remains largely untested.

5. Case Studies of Social Innovation: Empirical Evidence for Social Innovation Generating Positive Impacts on Social, Economic and Environmental Outcomes

This section anatomises three case studies of social innovation and presents how social innovation initiatives can generate positive social, economic and environmental rural development outcomes, which make the concept potentially useful, and which may also improve understanding of the scope for both large-scale and local transformative change. The cases exist within the institutional contexts of different countries (United Kingdom, Austria and Italy) and have been supported by different policy means. All three cases were screened by a selection process in SIMRA to determine that they did, indeed, comprise social innovation. Although the boundaries between social, economic and environmental social innovations are often blurred, one of the cases is predominantly social, one predominantly economic and one predominantly environmental in character. For each case, we will look at why they emerged, how they evolved and what role they fulfil. We will consider how policies and institutions have supported them and their trajectory over time. In each case, we will describe the social innovation and explore its social, economic and environmental impacts and outcomes.

5.1. Scottish Example: Huntly and District Development Trust (HDDT)

5.1.1. Where?

Huntly is a small town of c 4000 people just over 60 km northwest of Aberdeen, surrounded by mixed farming and forestry. Like many small towns, it has deindustrialised, in its case as a result of the decline of woollen textiles industry, and its market functions have been compromised by improved mobility to larger service centres. Huntly was too far from the hubs of activity along the North Sea ports to benefit substantially from the North Sea oil and gas boom. Its compromised future was recognised by the municipality, and a time-limited municipal project was instigated, which lasted from 2005 to 2008.

5.1.2. What Created the Trigger for Social Innovation?

At the end of the municipal project, a decision was made to try to prolong the project activity by creating a local development trust to build on the established momentum. Development trusts are third-sector agencies that operate in a defined spatial area (a village, a town or town and hinterland) to promote sustainable development outcomes. They operate alongside municipal government, have a constitution and a board of trustees and may have paid officers. They compete for discretionary public and charitable funds to deliver their strategic vision and design and deliver projects, often in partnership with others. Most funding from public sources is fixed term and project-specific. Survival of a trust requires an ability to win project funds congruent with their purposes. Huntly and District Development Trust (HDDT) was thus locked into cycles of fundraising from national and EU sources to enable them to act in support of community-led development.

During the early period of the Trust’s existence, several large-scale commercial wind farm projects were developed in the immediate hinterland of Huntly. HDDT succeeded in using the Scottish Government’s policies for community benefits from onshore wind farms to provide a limited and more regular income stream. Taking advantage of another Scottish policy, community land ownership, HDDC acquired a small upland farm with support from the Scottish Government’s Community Land Scheme. HDDT’s challenge was to break out of the uncertain and sporadic funding that came from fixed-term projects and create a certain and long-term income stream through their own wind energy development. They faced major regulatory hurdles and significant challenges over raising finances. The very existence of the Trust was threatened by uncertainty as to whether the project would proceed, but it was secured and placed the Trust on a sound financial footing.

The Trust made substantial use of arm’s length publicly funded institutions created by the Scottish Government to achieve its aim of owning renewable energy resources. Scotland, perhaps more than any other region/nation in Europe, has created multiple platforms for community-based developments. Most significant in the wind energy development was Community Energy Scotland, which, through its Community and Renewable Energy Scotland (CARES) scheme, provided risk capital, loan finance and advisory support. Without this, the project would not have happened. Equally importantly, the Community Land Fund grant-aided the purchase of the farm that provided the site on which the wind farm was developed.

As a result of these investments, HDDT has secured a long-term income stream for the next 20 years, which has enabled it to take on even bigger community projects and occupy a position as a pivotal community development agency. Its projects support low-carbon mobility, local food, local heritage, community leisure and town centre redevelopment.

5.1.3. How Did the Activity Comprise Social Innovation?

HDDT’s engagement with renewable energy was not the first occasion in which a development trust had engaged with renewable energy, but they were early adopters. Other groups in the northern and western isles of Scotland had already developed community-owned wind energy. Their recognition that renewable energy could underpin wider community-based development ideas was not especially novel. Therefore, HDDT’s activity is more an imitative replication of emerging models of local development than completely novel, driven by a highly motivated and capable team strongly grounded in the community.

5.1.4. Explaining HDDT’s Successes and Failures

The success and achievements of HDDT are primarily a product of a team of trustees and staff who refused to give up when many groups might have ceased to exist and whose actions have connected them to a range of public policies and public agencies that have built a platform for transformational social innovation in reviving the small town. Their success owes much to being able to “pick winners”, that is, to recognise projects with potential to create transformative opportunity within a clear strategy. The wind energy project, the community acquisition of the farm and subsequent town centre buildings have been the foundations of their success, with the potential to generate GBP 10 million of investment in the next 20 years and leverage in about the same with the co-financing from HDDT guaranteed for a long time.

As the financial settlement from central to local government has reduced other funds, the trust is increasingly reaching into arenas of activity that have hitherto been delivered by the public sector. A more locally grounded third-sector model of community development has taken root, underpinned by the long-term income stream from renewable energy. Huntly still remains a relatively poor community. The underlying economic weaknesses remain, and its socioeconomic profile is still relatively disadvantaged, but through its third-sector-led investments, it is now pioneering a pathway towards sustainable low-carbon development, which may prove a considerable advantage in a post-carbon world.

5.2. Austrian Example: The Creative World of Apprenticeship

This case description is based on an extensive case study by Lukesch R. et al., 2019, on updated information from the project website (http://www.lehrlingswelten.at/ (accessed on 3 March 2022)) and on personal information from the project manager, Erika Reisenegger (7 December 2021).

5.2.1. Where?

Styria (Steiermark) is one of nine federal states, located in the southeast of Austria. The area where the innovative action sprung up is its eastern part, where the Alps roll out towards the Pannonian plains, featuring a hilly, highly diverse landscape, which presents itself as a mosaic of meadows, woodland, fruit orchards, vineyards and valley fields, where corn and pumpkin—to produce the precious pumpkin seed oil for which the area is well-known—grow. The Local Action Group (LAG; Zeitkultur—Oststeirisches Kernland (Zeitkultur—Oststeirisches Kernland literally means Time culture—East Styrian heartland)) has operated since 2007, stretching over 16 municipalities and about 43,000 inhabitants. Graz, Austria’s second largest city, can be reached in less than one hour, and the Austrian capital, Vienna, within two hours. In spite of the attractive environment and pleasing living conditions, the area suffers from structural weaknesses, a decline in the economic power of settlement centres, a constant drain of youth towards the urban agglomerations and a thinning out of basic services and infrastructures in the rural parts in contrast to the district centres. Although East Styria’s population balance seems to be rather stable over time, there is a strong demographic shift from rural communities to the urban centres.

5.2.2. What Created the Trigger for Social Innovation?

The local action group is an outstanding practitioner of the LEADER method. The office hosts a topical library with publications ranging from philosophy and social sciences to hands-on technical guidance for climate-neutral practices. The overall approach of the LAG is rooted in the tradition of “slow” approaches (slow food; città slow, etc.), and both the LAG chairman—the mayor of a small municipality—and the LAG manager—acting as such since the founding days—are strong exponents of LEADER as an instrument for enabling and fostering social innovation. In its early stages, the LAG held a series of strategy workshops in which it identified a growing gap between the local small-structured craft-based economy, suffering from chronic deficiency of skilled workers with subsequent problems of intergenerational succession on one side, and the teenagers lacking job perspectives after having accomplished their secondary education cycle on the other. Conventional approaches to career orientation did not deliver. The worlds of local entrepreneurs and rural youth kept drifting apart.

5.2.3. How did the Activity Comprise Social Innovation?

In their quest for a solution, the LAG members and staff discovered that a similar challenge had been met some 15 years ago in the westernmost part of Austria, where a group of architects and designers belonging to the Werkraum Bregenzerwald (Werkraum Bregenzerwald can be translated as Factory Space Bregenzerwald, a rural area in the federal state of Vorarlberg; the mentioned project had also been funded under LEADER) had developed so-called “work boxes” together with entrepreneurs of different crafts and trades. Basically, these work boxes were cubicles containing modular elements, which unpacked and unfurled illustrate the main features of a particular craft. The East Styrian LAG developed the originally static concept of “work boxes” into something interactive and mobile with the help of a Werkraum designer and assembled, with the assiduous but not always easily manageable participation of local entrepreneurs, vocational trainers and students/apprentices. To date, 25 work boxes (from hairdresser to carpenter, from cook to pastry baker, including crafts falsely stigmatised as forlorn, such as book printers) have been designed and built. These novel work boxes are not just exhibition objects; they serve as workbenches on which real artefacts can be crafted. They are utilised during practical career orientation events in secondary and primary schools around Styria. In these events, pupils and students work on the workbenches. Since 2014, 7000 teenagers have been involved, accompanied by 500 local entrepreneurs, who participate as volunteer mentors in these career orientation days, which are mostly held in the gym halls of local schools. The side effect of their voluntary contributions is that they get to know the boys and girls (and vice-versa) and may invite them for trial days in their businesses and eventually get to hire them as apprentices upon leaving school.

A glimpse at the LAG website evidences that the LAG continues to act innovatively. Undoubtedly, the Creative Worlds of Apprenticeship project suffered a slowdown in the times of COVID-19-related restrictions, as it is designed for direct interaction. However, it has spawned projects in other Austrian regions and in other EU member states. According to the project manager, the project keeps evolving with the needs that arise during implementation. One of the more recent developments is a mentoring program for entrepreneurs to better harness the internship time for young interns and trainees. Employees of local enterprises have signed up to a training program for mentors organised by Chance B, a highly esteemed third-sector organisation and social entrepreneur located in East Styria (www.chanceb-gruppe.at/ (accessed on 3 March 2022)).

Still more ingeniously, a freight container is being adapted as a “mobile work room” containing the abovementioned work boxes, a kitchen and a bar, two balconies and a lounge space. The trailer is redesigned in such a flexible manner that it can be used as a crafts workshop, an art studio and as a stage for creative performances. The trailer, described as a “spectacular learning and meeting space”, can be moved by a truck from one place to another, expected to stay for one or two weeks. In cooperation with other local action groups, the project pertains to the whole State of Styria from the very onset. With the trailer project, the Creative World of Apprenticeship reaches out to children who are counted among the NEETs (those not in education, employment or training). Even before actually starting, the project has achieved a place among the top five in the category of “socially inspiring futures” of the Rural Inspiration Award conferred by the European Commission.

5.2.4. Explaining the Creative World’s Successes and Failures

The success of the Creative World of Apprenticeship mainly hinges on the local action group’s self-understanding as a promoter of social innovation. The project manager is located in the LAG office, backed up by the LAG manager. Thus, the LAG can be considered a social entrepreneur. The Creative World of Apprenticeship is recognized within and also far beyond the borders of the LAG.

Finally, the gap between local business and local youth appears to have narrowed; however, there is still a way to travel to get the traditional institutional fabric to integrate the innovation into their processes. What still needs to be accomplished in the near future is to disconnect the management of the innovative action from the nursing shell of the LAG. This has been partly accomplished through the involvement of the third-sector organisation Chance B. However, the key stakeholders in the field of career orientation and support to MSME (labour market service, economic chamber, vocation training centres) still remain on the edge of the playing field and are not taking the initiative into their own repertoire of practices, although there are some highly committed individuals in these organisations who never tire of stressing the benefits of this approach and who nurture hopes for a consolidation of the approach beyond LEADER. Until this happens, the LAG keeps up the momentum; however, LEADER is genomed to initiate innovative practices and not to implement them in the long term. This issue will be addressed by an external evaluation and a strategy retreat in early 2022.

5.3. Italian Example: Learning, Growing, Living with Women Farmers

“Growing Living with Women Farmers” is a social cooperative offering dispersed daily childcare service provision on farms, complementing the offer of social services in rural remote areas of South Tyrol.

5.3.1. Where?

The social cooperative is based in the municipality of Bolzano but delivers childcare services directly on farms, commonly in remote rural municipalities distributed across the territory of the Autonomous Province of Bolzano/Bozen (South Tyrol, Italy). The Province of South Tyrol is a territory mainly covered by mountains (97% of surface area) located in the northern part of Italy. The settlement structure is characterized by five medium-sized municipalities (with populations ranging from 10,000 to 25,000) and sparsely populated rural valleys in which the majority of the population lives. Agriculture is an important sector, contributing 4.5% of the added value of the province (in comparison to the national average of 2.2%), and it is represented by a very strong lobby of farmers at a political level. Nevertheless, more than 60% of the farms rely on agricultural activities only as a secondary source of income, demonstrating the low profitability of mountain agriculture in contrast to lowland agriculture.

5.3.2. What Created the Trigger for Social Innovation?

The cooperative started in 2007. It was created on the initiative of the spokesperson of the women farmers, followed by a network of women farmers willing to create both professional and qualified employment opportunities and economic independence for women farmers living in remote communities who otherwise had to move to cities for jobs. At the same time, it responded to the collective need to provide delocalized high-quality childcare service on farms for parents wanting to raise their children in a rural environment (practice learning with nature–nature pedagogics). The women farmers wanted to offer cooperative/trans-sectoral services combining agriculture and social services, an innovative model of social services different from the traditional tagesmutter (child minder) services existing in the province of South Tyrol.

5.3.3. How did the Activity Comprise Social Innovation?

This initiative developed in response to unmet social needs—creating opportunity for women farmers to improve their social and economic conditions compared to their male relatives—and societal needs to encourage interactions with nature, with the more general aim of enhancing the potential for liveable rural areas.

The founder of the initiative was the former spokesperson of the association of women farmers in South Tyrol, politically active, very well-known and rooted in the local community and herself a farm woman with five children. To develop her idea, in the early 2000s, she invited the network of women farmers to share knowledge and experience and to be part of the project idea. Representatives of the main farmers’ union of the province were invited but initially showed scepticism towards the idea. The turning point was the financing of the project through European Social Funds, which provided the financial means to implement the idea. In 2005, preparatory actions started with the setting up of a childcare service on a farm, including a training course and feasibility study. When the innovator presented the project to women farmers, they were not very supportive, as they did not believe the project would change their socioeconomic situation. Therefore, she arranged a training course on how to become childcare providers and had to persuade women farmers to attend. She also opened it up to other rural women who were motivated to do social farming. In 2007, the social cooperative “Learning, growing, living with women farmers” was created, and the first on-the-farm childcare service started. After the training course, women farmers created their own activity. The childcare service includes individually adapted care accommodating up to six children, flexible care hours, integration into the family structure, transmission of traditional and cultural values, environmental education, summer care and care for children at different events. The farm became a place for rural education, social interaction and transmission of local knowledge/community values.

Currently, more than 100 child minders associated with the social cooperative offer childcare services in South Tyrol. This service supports existing public services and responds to local demands, especially in peripheral areas. After 10 years, the cooperative now employs more than 100 women who enjoy greater responsibility on the farm, economic independence and job security. Overall, they provide childcare on their farms to more than 500 children across the region. The political activities of the initiators were crucial to securing political support. Strong support came from the establishment of a national law on social agriculture in 2015. Due to its success, the actors of the initiative engaged in policy processes aiming at institutionalizing the service as belonging to social agriculture and at improving contractual conditions for workers in the third sector. This triggered a provincial law in 2018, which recognized social farming as an important field of activity.

5.3.4. Explaining the Successes and Failures

The social cooperative “Learning-growing-living with women farmers” has become a well-established provider of childcare service on the farms in remote rural valleys of South Tyrol, delivered by women farmers using methods of nature pedagogics. The service provided has become embedded in the policies of the public service, which provides complementary provision within the province. Overall, the initiative had impacts on the economic, social and political domains, mainly improvement tin he conditions of the rural communities in which the initiative emerged and developed. First, it has offered social and economic opportunities for women for social inclusion and empowerment; farm-based entrepreneurship opened new possibilities for women farmers to gain a personal income and become economically independent and empower women farmers to continue living in rural areas while creating for themselves a professional role on the farm and gaining independence from the male members of the family. Second, it has created opportunities for business diversification, making farms more resilient to changes. The farm expands to become a place of learning, leading mountain agriculture towards a new paradigm of agriculture characterized by various forms of income diversification, offering a complementary and alternative setting for environmental education. Finally, it changed the role of women on the farm and the way society perceives women in rural areas. By challenging attitudes and social practices, women farmers have been recognized and acknowledged by the society in the case study region [66,67].

There are three main ingredients for the success of the initiative: (a) the presence of strong leadership of the initiators who developed the social innovation idea and capacity to take action, (b) collective action originating from a strong social capital (collaboration and trust), and (c) political support that created the framework conditions for the initiative to develop and spread in the region. A significant remaining issue relates to the work–life balance of women farmers offering childcare service on the farm. Additional activities besides work on the farm can result in overwhelming hours of female work. This balance is difficult to guarantee because being economically independent for the women involved is at the expenses of their free time. This is a topic for which more work and consideration is required by the parties involved.

6. Are there Negative Impacts and Risks of Social Innovations?

So far, most attention has been focussed on the positive impacts of social innovation [11], as have our case studies. Most social innovation thinking is grounded in a strong normative belief that it delivers societal benefit. However, society, as an aggregate, comprises many different groups and interests. Social innovation can have both positive and negative outcomes, and what is good for one group may not be good for all. For some time, a “dark side” narrative of social innovation has been posited. It has been explored mostly in an urban setting [53,68,69], but it is worthwhile exploring the salience of this dark side in the different geographical setting of marginalised rural areas. For example, it is possible that some community energy projects compound disadvantage rather than improve access to renewable energy and address fuel poverty? Is community energy always a desirable development when, particularly with wind energy, it can be so contested by different groups within the same community and promote division, even if it has potential for local economic and environmental benefits? Likewise, are social movements such as those of the gilets jaunes in France a legitimate crie de coeur from those neglected by existing policy means or a retrograde retreat into nativism?

In contrast to the blunt and well-worn term “innovation”, the adjectivized term “social innovation” is value laden. It insinuates a double dividend: the betterment for a specific group going along with, or even leading to, a better society. This leitmotif runs through almost all definitions of social innovation. However, life means change, and changes are the only constant in our lives. Social innovations are usually observed and gauged within a middle-range time frame, which is not too short (all our case studies look back on a history of more than 10 years), but what was a clear bearer of benefits for some time may transform into something completely different, driven from generational change or jogged about by the intemperate winds of societal change, i.e., today’s solutions are tomorrow’s problems (quote attributed to Bruce Sterling at the American Center for Design “Living Surfaces” Conference, San Francisco, October 1994). The normative charge of the term social innovation may lure one or the other protagonist into an advocacy role in which s/he might deny negative outcomes of (once) socially innovative actions and brush off concerns about its capacity to compound inequality.

This risk is also real from a policy perspective: that a policy designed to reduce spatial disparities and inequalities actually compounds them. If, as is suggested by Muringani et al. [37]’ strong bridging social capital is associated with higher rates of growth, a policy that supports community action across all communities will tend to lead to the most activity in communities that have high levels of bridging social capital, thereby increasing spatial disparities in a more granular analysis. A second form of compounded inequality occurs where community activists represent sectional rather than collective interests and draw down support to help already privileged local elites. Such observations make a compelling case for a much closer and more critical analysis of power than can be found in most academic or institutional evaluations of social innovation.

7. Discussion

There is a powerful narrative on existing wicked problems and grand societal challenges that need addressing in a rural context at multiple scales and by diverse agents. The tensions between the market and society lie at the heart of many of the responses described by the umbrella term of social innovation. This can be interpreted as a Polanyian double movement [70] of society kicking back at the deeper penetration of markets. Karl Polanyi was deeply aware of these tensions between the extension of the market into new areas and the resulting “double movement” arising from increased market penetration and contemporaneous social dislocation and resistance. That resistance can sometimes catalyse alternative ways of doing through new processes by new locally grounded formal and informal institutions. We might wish to label such action social innovation. Levien and Paret [71] offer what they describe as “compelling evidence for the existence of a latent global countermovement, in the form of a widespread increase in desire for re-embedding the market at a time of global disembedding”. This can be seen as propitious circumstances for initiating social innovation.

Social innovation, bottom-up activities, coproduction and community-led local development are all terms used to describe the conceptual tools developed to tackle the current crises in socioecological systems. Blasch et al. [72] argue that the grand societal challenge of climate change “could be solved by new and more dynamic forms of bottom-up, dispersed, and multi-level governance … (and) that polycentric governance can work well when central goals—such as fighting climate change—are shared, when actors develop trust because of their continued mutual interactions in local initiatives, and when systematic evaluations take place and translate back to the identification of best practices that can be scaled up”. This looks like social innovation, but the term is unused by them. The growing interest in coproduction, both between different actors and between different extant and emerging technologies, offers yet another way of exploring these multiple possibilities for restructuring. Jasanoff et al. [73] talk about coproduction referring “not only to formal constitutional principles by which state institutions legitimate their relationships with citizens but also to tacit reconstructions of state–society or public–private relations …(which can be associated with) … the emergence of radically transformative visions which had not previously appeared on the radar and allows us to explore how they become thinkable and tangible”. Beck et al. [74] describe these processes as sociotechnical imaginaries that may help create radical transformational possibilities, but we are reminded by Cleaver [16] that local contexts can have a profound effect on the formation and success of new institutional arrangements.

Sustainability scientists have deepened their engagement with the idea of coproduction as a means of addressing the ecological crisis [49]. This also looks like social innovation. There is some commonality in many of these observations. The uneven pressures of globalisation on different places, the differences of institutional bricolage and the politically mediated possibilities for local action that stem both from specific political cultures and distinctive policy arrangements mean that social innovation is necessarily a coconstitutive action between civil society actors and others. Such actions may lead to breakthrough moments when new opportunities emerge to redirect and change outcomes. However, in rural development, the only certainty is that spatial and temporal differences of both social capital and institutional architecture will mediate outcomes and create uneven responses, constrained or less constrained opportunities, and diverse and varied local outcomes. Whether a social innovation lens is the only tool to explore these differentiated outcomes is a moot point, but framed around the idea of reconfiguration of institutions, it allows for an insightful exploration of how changes in socioecological systems occur and how they can help to deliver enhanced sustainable development outcomes.

Social innovation usually arises where there is a community-led response to a crisis or perceived problem; or occasionally as a result of community-led seizure of an opportunity. A community-led response is contingent on community capacity, and the capacity will vary from one social innovation to another. A combination of strong social and human capital with bridging capital to key support agencies and effective leadership may help underpin successful delivery. Strong social capital and a long tradition of economic cooperation tend to enable social innovation. Several studies of social innovation [32] confirm that social innovation is driven by collective action originating from a strong social capital, where cooperation is important [35]. In addition, strong ties based on mutual acquaintances, recognition and trust were relevant in shaping members’ community ties and their capacity to act [35].

Equally important is an available niche in the ecosystem of supply and demand of goods and services or in the socioecological system more broadly. Vacant niches are normally a product of market or state withdrawal (e.g., social care services, retail services), or failure of the market or the state to provide a new sought-after good or service. Such niches are more common where there is a public good with high delivery costs (e.g., ecosystem services) in an environment of weak public policy support. Niches can expand or contract depending on dominant values and evolving policies. As we saw in the Austrian example, policy and practice gaps can be niches for social innovation. The advance of neoliberal values has led to a withering of the welfare state and the marketisation of what were formerly public services. Where markets are unprofitable and weak, this may lead to the withdrawal of a service. Alongside such changes, an advance of communitarian values may make community bodies more willing to take on new responsibilities, as is evident in community-owned shops, social care enterprises, etc., which are much more common than in the past 30 years. We can label these evolving arrangements and responses a local innovation ecosystem, an evolving institutional bricolage, bottom-up development, endogenous development, community-led local development or social innovation. What is really significant is the outcome, which, in Wright’s terms, can be driven by social actors finding vacant niches in “interstitial” transformation, working with public sector actors to deliver “symbiotic” transformation and, perhaps in some rather exceptional circumstances, delivering ruptural transformation.

Social innovation is most likely to flourish where there is a significant unoccupied niche (an unmet need) and where there is multi-scalar support for a community-led model of provision and a local cadre of engaged actors. Elsewhere [75], we have argued that the performance and outcomes of this essentially triadic relationship between the state, intermediary agency and local actors will underpin the success of the social innovation or community-led action. The alignment of agency at these levels is by no means guaranteed. The translational agency may be weak or local social capital may be lacking to drive the social innovation. Local action groups are the epitome of such intermediary agencies (called intermediary support systems/ISS in [75]. In the Austrian case of the Creative World of Apprenticeship, the LAG has deliberately taken on the role of a social entrepreneur, which means that the core of innovative actors nests inside the LAG, not promoted by the LAG, but acting on behalf of the LAG. This was deliberately decided in order to get the innovative action started because no other actor in this relatively disfavoured rural area was in the position to reinvent itself as a niche player or to craft strategic cooperation ties with other actors on the other side of the gap. One reason may lie in that they (labour market services, vocational training institutes, agricultural and economic chambers) are all branch offices of state-based headquarters, simply lacking the autonomy to do so. Another reason may lie in the small-structured rural fabric, where all actors of sorts have very similar problems to face, but no off-the-shelf solutions can be applied. Solutions rely on personal exchanges and elaborate agreements, which emerge from nicely crafted events, such as the career orientation days: familiar and yet a little different.

The territorial approach and integrative aspect of CLLD/LEADER is, in many areas of Europe, the rare if not only resource for innovative actors at the microregional/intercommunal level to get support for an innovative action that spans the gap between the sectoral and institutional silos. This does not mean that this ambition is met accordingly everywhere, but the opportunity is intact as long as CLLD exists in the repertoire of European cohesion policy instruments. With that in mind, one may agree with Jasanoff [73], who notes that the European Union has become a nurturing force for civic re-engagement in both policy making and delivery.

8. Conclusions

We find social innovation still to comprise a contested conception—some might say a chaotic conception [76]. In the search for better understanding of development trajectories and possibilities for disadvantaged areas, particularly those delivered by new hybrid institutions, we should be unsurprised that some actors operating in the field use the term social innovation with different meanings and that some use different terms altogether. We see no reason to assert the supremacy of one term over another but argue for greater conceptual clarity, especially in how social innovation concepts might inform policy. The fact that social innovation has attracted such interest in Europe and beyond should lead to serious consideration of what value it can add to the existing repertoire of concepts, how it connects to theory, what impacts social innovation can achieve in practice and whether it should be embedded as a core idea in policy formation and implementation.

8.1. Theory

It is not easy to place social innovation in an obvious theoretical framing, whether the focus is its distinctive form of innovation, its predominantly social character or its varied spatial manifestations. Undoubtedly, social innovation, in all its definitions, is spatially and temporally contingent and highly variable over time and space; and its motivations are diverse and potentially contradictory. Claims of its transformational capacity at a national or regional level are almost certainly exaggerated, but Wright’s [44] idea of interstitial or symbiotic transformative possibilities at a local scale merit serious attention. Like many social theories, theories of social innovation are permeated with normative intent, but the normative content is not consistent, being derived from many disciplines, from managerial science to critical social theory. There is also debate as to whether social innovation belongs within the sphere of civil society and third-sector activity or whether it can embrace public sector and private sector activity too. In a sense, the increasing hybridity of partnership forms, and the emergence of new models of collaborative provision cloud this point, but we see the centrality of civil society agency as a defining characteristic, a view not entirely consistent with mainstream European Commission definitions, which embrace the belief that municipal and state-led policies and initiatives can also comprise social innovation.

Social innovation is not alone in being a new concept, subject to definitional confusion and the embrace of multiple theoretical perspectives and disciplines. The idea of coproduction has more singular roots in science and technology studies but is still subject to variable interpretation when applied to fields that overlap strongly with work in social innovation. It focuses primarily on the processes of new institutional formation, which create the ground conditions for sustainability enhancement. Social innovation also acknowledges that new liaisons and institutional forms among multiple actors and stakeholders are important means of negotiating practical pathways towards sustainable development.

8.2. Practice

Where social innovation occurs in specific communities or sectors, it can generate highly positive impacts, which, on occasion, appear to outperform the alternative ways of doing. It is normally a response to a crisis of existing modes of provision of a service. Such a crisis might be one of service failure or inadequacy from either state or market providers or from a failure to accommodate environmental externalities. In our case studies, we illustrated that social innovation can best deliver enhanced outcomes where there is good alignment and trust between civil society actors, municipal and public policies and where bridging agencies provide a nurturing and supportive context.

Although social innovation appears, at times, to have the potential to deliver more sustainable and just outcomes than some other forms of social action and service provision, it also has the capacity to compound inequality, thus compromising the BEPA definition and perhaps the European Union’s cohesion aspirations. This may happen in the longer term if the context parameters gradually shift; or in the course of scaling up or scaling out into contexts to which the action is not tailored. Local elites can capture the benefits; or favoured local civil society groups become the beneficiaries of public sector largesse.

8.3. Policy

Social innovation seems likely to have continued salience in specific fields where the policy community has adopted the concept, most strongly in the EaSI programme of the ESF+ and in relation to the transition to renewable energy but with much more patchy coverage in other fields. In the community renewable energy domain, social innovation retains its vibrancy as a concept and has been subjected to robust and critical review by the scientific community, albeit one with a framing in transition theory. Alongside its presence in these fields, established concepts, such as CLLD and endogenous development, will most likely continue to frame major policy interventions for rural Europe.

We think it unlikely that social innovation will displace other established conceptual lenses that already inform important strands of public policy. Indeed, it may be displaced by them, absorbed into them or superseded by ideas such as coproduction, which has evolved beyond its original meaning to include many ideas that resonate closely with social innovation. How it interfaces and interacts with policies such as smart villages in EU rural policy has not yet been elucidated. There is a perennial tension between the neoliberal and communitarian strands of policy interest in social innovation, seen, on one hand, as a desirable stop-gap response to market failure and austerity politics and, on the other hand, as the product of a much more challenging grassroots communitarianism.

Social innovation seems likely to continue to be dogged by conceptual and definitional uncertainty associated with its diverse origins and burdened by the excessive zeal of some of its protagonists. However, in its focus on new forms of formal and informal institution building and activities that address long-standing societal challenges, it at least leads us into exploring new ways of thinking and doing, potentially capable of delivering enhanced societal well-being and sustainability where other institutions have struggled and/or failed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.S. 60%, R.L. 20%, E.R. 20%; methodology, B.S. 60%; R.L. 20%, E.R. 20%; formal analysis, B.S. 60%, R.L. 20%, E.R. 20%; investigation, B.S. 33%, R.L. 33%, E.R. 33%; data curation, B.S. 33%, R.L. 33%, E.R. 33%; writing—original draft preparation, B.S. 60%, R.L. 20%, E.R. 20%; writing—review and editing, B.S. 60%, R.L. 20%, E.R. 20%; funding acquisition, B.S. 20%. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project on which this paper is based has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement 677622.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The information regarding the SI initiatives were collected and analyzed within the framework of Horizon 2020 project SIMRA. Data collection and research design complied with the legal guidelines on research ethics as required under rules for receiving EU H2020 funding (Regulation (EU) 1291/2013, 11 December 2013), and the internal arrangements of individual project partners. The ethical clearance procedure is described in the SIMRA Deliverable 5.1 (http://www.simra-h2020.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/SIMRA-D5.1_Case-Study-Protocols-and-Final-Synthetic-Description-for-Each-Case-Study-1-1.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2022)).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (E.R.) starting from 2023. The data are not publicly available due to conditions associated with their collection (e.g., could compromise the privacy of research participants], in line with ethical clearance obtained. Further details of the case studies are available on the SIMRA project site, www.simra-h2020.eu/index.php/simra-case-studies/ (accessed on 3 March 2022).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Georgios, C.; Barraí, H. Social innovation in rural governance: A comparative case study across the marginalised rural EU. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millard, J. How social innovation underpins sustainable development. In Atlas of Social Innovation: New Practices for a Better Future; Howaldt, J., Kaletka, C., Schröder, A., Zirngiebl, M., Eds.; Oekom Verlag GmbH: Munich, Germany, 2018; pp. 41–43. [Google Scholar]