1. Introduction

Hybrid satellite–terrestrial relay

schemes have emerged as a promising solution to overcome the inherent limitations of conventional satellite and terrestrial systems [

1,

2,

3], where terrestrial relay stations are used to support the communication link between the satellite and ground users. The

models can enhance the system throughput and reliability, and they are considered as a key enabler for beyond-5G and 6G networks. In recent years, research on the

systems have advanced in several closely related directions, including system reliability improvement, physical-layer security, spectrum sharing, and advanced multiple-access schemes. For example, the authors in ref. [

4] presented a space–air–ground free-space optical network that employs a high-altitude relay to improve the robustness of satellite communication links. Beyond reliability enhancement, security has become a critical concern in the

systems due to the broadcast nature of satellite transmissions. In refs. [

5,

6], the authors investigated the secrecy performance of the

schemes in the presence of eavesdroppers. Specifically, ref. [

5] focused on the secure

scenarios with multiple eavesdroppers, whereas reference [

6] introduced relay station selection methods to enhance secrecy outage probability. The authors in ref. [

7] analyzed the relationship between intercept probability

at the eavesdropper and outage probability

at the legitimate receiver for the secure

models. In addition, reference [

7] introduced both full relay selection

and partial relay selection

to improve the security–reliability trade-off, under the impact of co-channel interference. These works collectively indicate that relay selection plays a pivotal role in balancing reliability and security in the

networks.

Another important research direction considers spectrum efficiency through cognitive radio techniques. Published work [

8] proposed the

schemes operating in a cognitive radio environment, where the satellite and the relay station are secondary transmitters, and they are allowed to use the licensed spectrum if their transmissions do not degrade performance of the primary users. Meanwhile, full-duplex relaying has been explored as an effective means to further enhance spectral efficiency in the

systems. In ref. [

9], full-duplex relaying techniques were applied into the

scheme, allowing the terrestrial stations to transmit and receive data at the same time. Moreover, the

technique was applied to select the best terrestrial station to improve the throughput and the

performance, under the impact of co-channel interference. More recently, intelligent reconfigurable environments have been incorporated into the

models. Reference [

10] presented the

scenario assisted by reconfigurable intelligent surfaces

. In contrast to the traditional relaying schemes, where the relay nodes actively process the received signals,

-aided relaying models rely on passive reflective elements that reflect the incoming signals toward the desired ground users in an optimized way. Compared with conventional active relays, RIS-assisted relaying offers a low-power and hardware-efficient alternative, making it attractive for satellite–terrestrial integration.

In parallel, non-orthogonal multiple access

has been introduced into the

systems to improve connectivity and spectral efficiency. In refs. [

11,

12,

13],

is applied into the

systems, enabling the satellite to transmit different data to multiple ground users at the same time. In addition, the ground users have to use successive interference cancelation

to extract their desired data from the received signals. In ref. [

11], the authors derived expressions of

for the

scheme, where the direct links between the satellite and the ground users are assumed to exist. The authors of ref. [

12] studied the

and

performance for the secondary users in the secure cognitive

scenarios. Reference [

13] evaluated the

performance of multi-relay

models. These studies demonstrate that

is an effective multiple-access technique for

, but they mainly focus on fixed-rate transmissions.

Unlike the aforementioned published works, this paper considers the

scheme using Fountain codes

.

[

14,

15,

16] have proven to be effective in wireless networks due to the simple implementation and adaptability to varying environmental conditions.

are particularly well-suited for multi-user broadcast networks since the transmitter can generate encoded packets from its original data, and continuously send them to the intended receivers. In addition,

allow the receivers to recover the original data once a sufficient number of encoded packets

have been collected, even in the presence of packet losses. In refs. [

17,

18], the authors considered the

schemes employing

. The authors of ref. [

17] evaluated the

and

performance for the secure

scheme, with the presence of a passive eavesdropper. Moreover, reference [

17] employs a cooperative jammer that not only disrupts the eavesdropper with jamming signals but also works with the ground user to eliminate the noises from the received signals. Published work [

18] studied the

trade-off for the

multicast schemes using

and PRS. Unlike refs. [

17,

18], this paper studies two-way

models, while refs. [

17,

18] only consider the one-way

ones. However, these works do not address two-way information exchange, which is essential for bidirectional satellite–ground communications.

Two-way relaying

(refs. [

19,

20]) has attracted significant attention due to its capability to improve spectral efficiency and throughput by allowing two sources to communicate simultaneously in both directions through one or multiple intermediate relays. In a conventional

model [

21], during the first two phases, the first source transmits its data to the intermediate relay, which then forwards the data to the second source. Similarly, the next two phases are used to relay data from the second source to the first source via the relay node. As a result, the conventional

model uses 04 phases, and it achieves a throughput of only 2 data over the four phases. To enhance throughput for the

models, the relays in ref. [

22] perform an

operation on the data received from two sources at two first phases, and then transmit the

packet to both the sources in the third phase. As a result, the

models in ref. [

22] only use three phases, and they are called a Digital Network Coding

-based

. Published work [

23] introduced two-phase

scenarios using Analog Network Coding

, where the relays amplify the signals received from two sources in the first phase, and then transmit the amplified signals to both the sources in the second phase. In refs. [

24,

25], the

and

techniques are jointly employed at the relays in the

models so that only two phases are used. Indeed, in refs. [

24,

25,

26], two sources at the same time send their packets to the relays which will perform the

technique to extract the received packets. Next, the relays perform the

operation over two packets before broadcasting the

packet to two sources in the second phase. Hence, both the

schemes using

and the

schemes using

and DNC only use two phases for the data exchange.

Until now, there have been several reports related to

models [

27,

28,

29,

30]. The authors of ref. [

27] examined the

system integrating simultaneous wireless information and power transfer. Reference [

28] analyzed the

performance and the throughput for the

system using

and considering the effects of hardware impairments. Also, the impact of hardware imperfection on performance of the

networks was investigated in ref. [

29], emphasizing the practical constraints introduced by non-ideal transceivers. Reference [

30] proposed adaptive relay selection for TWR-HSTRNs, confirming that dynamic selection significantly improves throughput and spectral reuse efficiency. These studies confirm that the

networks can significantly improve spectral efficiency and throughput, yet their integration with Fountain coding and cooperative jamming remains largely unexplored.

Despite these extensive studies, the joint consideration of

, Fountain-coded transmissions, and cooperative jamming for physical-layer security has not yet been adequately addressed. Different from the related works [

27,

28,

29,

30], this paper proposes the

scheme using

and the cooperative jamming technique. In the proposed scheme, a satellite and a ground user exchange data via the help of terrestrial relay stations, with the presence of an eavesdropper. Using

, the satellite and the ground user generate

, and exchange them with each other. In the first phase, the satellite and the ground user at the same time transmit their

to all relay stations. The relay stations then apply

to extract the received packets. In addition, to degrade the quality of the eavesdropping links, a cooperative jammer is employed to transmit interference toward the eavesdropper during the first phase. In the second phase, one of the relay stations which can successfully decode the packets from both the satellite and the ground user is selected for data forwarding, using the

approach. The chosen relay performs the

operation on two received

, and subsequently broadcasts the

packet to both the satellite and the user in the second phase. Before the data transmission ends, the satellite, the ground user, and the eavesdropper attempt to collect enough

so that they can recover the desired data.

Now, the main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- -

First, we propose the novel scheme that integrates , , relay station selection, and cooperative jamming. The proposed scheme enhances system throughput through the use of and enables simple implementation and reduced delay by employing , improves communication reliability via and ensures secure communication through cooperative jamming.

- -

Second, under practical fading conditions, we derive exact closed-form expressions of , system outage probability , , and system intercept probability , and validate these formulas through simulations. In addition, all derived formulas are expressed in closed form, which makes them highly useful for system design and performance optimization.

- -

Finally, based on the analytical framework, we provide comprehensive performance insights that reveal the fundamental security–reliability tradeoff in the proposed scheme and demonstrate how critical system parameters influence both reliability and security performance.

The remaining structure of this paper is presented as follows.

Section 2 presents the system model of the proposed model.

Section 3 analyzes the exact and asymptotic

and

performance for the proposed scheme by deriving closed-form expressions.

Section 4 performs computer simulations to validate the derived expressions. Finally,

Section 5 provides conclusions.

2. System Model

In

Figure 1, we present a system model of the proposed

scheme, where the satellite

and the ground user

attempt to exchange their data via the help of

terrestrial relay stations denoted by

. We assume that there is no direct link between

and

due to being obscured. Let

and

denote the data of

and

, respectively. Using

the

node creates the

from the original data

. Then,

and

exchange their

via the help of the terrestrial relay stations. In order to successfully reconstruct the desired data

,

must gather at least

. In addition, due to delay constraints, the maximum number of

exchange rounds is limited by

[

18], where

It is worth noting that, in this paper, a generic

framework is considered without restricting to a specific implementation (e.g., LT or Raptor codes), since the analysis is performed at the packet level and depends only on the number of successfully received

.

Due to the presence of the eavesdropper

, the transmitters

,

, and

employ the randomize-and-forward strategy [

31] by randomly using code-books. Moreover, the cooperative jammer

is employed to generate the jamming noises over

, as well as to cooperate with the relays

for removing these noises from their received signals. We assume that the

and

nodes can securely exchange information about the jamming signals, enabling

to cancel them before decoding the desired data, while the

node is unable to do this [

17]. Similarly,

attempts to collect at least

packets

to reconstruct the original data

. Finally, all the nodes including

,

,

, and

are assumed to be single-antenna wireless devices.

We denote as channel coefficient of the link, where is a transmitter and is a receiver, i.e., Then, the corresponding channel gain is denoted by , i.e., Assume that all channels are block and flat, i.e., remains unchanged during one phase, and varies independently after each phase.

As given in ref. [

18], the satellite links (i.e.,

,

and

) are Shadowed-Rician channels, and

has the following probability density function

:

where

and

are the expected power of the multi-path and Line of Sight

components, respectively,

is a fading parameter, and

is a confluent hypergeometric function of the first kind [

18].

For ease of presentation and analysis, we can assume that the channel gains

and

are identical and independent, i.e.,

and

for all

Using [

18], cumulative distribution function

of

in (1) can be expressed under the following form:

where

For the terrestrial links, we assume that all the channels are Rayleigh fading. Hence, the channel gain

is an exponential random variable whose

and

can be expressed, respectively, as

where

,

, and

is a fading parameter of the

link. We also assume that the channel gains

and

are identical and independent, i.e.,

and

for all

and for all the

and

nodes.

We now describe the exchange of

in

Figure 1, which is carried out over two time slots. At the first time slot,

and

at the same time transmits

and

to all the relay stations, while

generates the jamming noises. Therefore, the received signals at

and

can be expressed, respectively, as

where

,

and

are transmit power of the

,

, and

, respectively,

and

are modulated signals of the packets

and

, respectively,

is transmitted signal of

,

and

are Gaussian noises at

and

, respectively.

Since the node

can cooperate with the jammer

to remove the jamming noise (the component

), Equation (5) can be rewritten as

Remark 1. Since the satellite is the well-equipped device, it is reasonable to assume that the transmit power of is higher than that of the ground user , i.e., . In addition, the channels between and the relay station exhibit the component. Moreover, the terrestrial link between and experience Rayleigh fading which does not contain . Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the link is better than the link. Similarly, we can assume that the link is better than the link. Therefore, the and nodes will decode the packet first. If the decoding of is successful, and will remove out from their received signals and will then decode [18]. It is noted that, if and cannot decode correctly, then they cannot also decode correctly because they cannot perform the operation. Finally, it is assumed that the Gaussian noises at all the receivers have zero mean and variance of .

From (7), we can express the signal-to-noise ratio

obtained at

for decoding

and

, respectively, as

where

and

Since the eavesdropper

cannot remove the jamming noises

out from the received signals, from (6), the

obtained at

for decoding

and

can be formulated, respectively, as

Considering the terrestrial relay stations which can decode both and successfully. Without loss of generality, we can denote the set of successful relay stations as , where and is the number of successful relay stations.

If

, then

, and, in this case, no operation takes place during the second phase. Let us consider the case where

; one of the relay stations belonging to the set

is selected by using the

method as

In (10), the selected relay station is denoted by , which is the relay providing the highest channel gain to the ground user .

Remark 2. In (10), the relay selection is based on the channel state information of the links, which can be easily performed through the exchange of local among the nodes. It is worth noting that this relay selection is difficult to implement between the relay stations and the satellite , because they are located far apart and hence the selection process would introduce a significant delay.

Next,

performs the

operation as follows:

and it will transmit the

packet

to

and

in the second phase, which is also overheard by

. Then, the

obtained at the node

can be expressed as

where

is transmitted power of all the relay stations, and

.

Remark 3. Firstly, we note that no cooperative jamming technique is performed in the second phase. Secondly, if the node can decode correctly, will obtain the desired packet by performing the operation as For the eavesdropper , it can only obtain successfully in the first time slot. Finally, can successfully obtain in two possible ways: (i) correctly decodes both and in the first phase; (ii) correctly decodes (but ) in the first phase, and from in the second phase, and then performs the operation between and to obtain .

Because the

exchange is realized into two phases, the channel capacity of the

link is calculated as

where

and

.

4. Simulation Results

In this section, we realize Monte Carlo simulations

to validate the formulas of

,

,

, and

given in

Section 3. We denote the exact theoretical results by

and the asymptotic theoretical results by

. To ensure that the

results converge to the

results (with the deviation between them ranging from 0.001 to 0.01), we perform from

trials to

trials for each Monte Carlo simulation. For analyzing the performance trends and evaluating the influence of the key parameters on the system performance, several parameters are fixed as follows:

, and

. The transmit power of the transmitters is set up as follows:

and

.

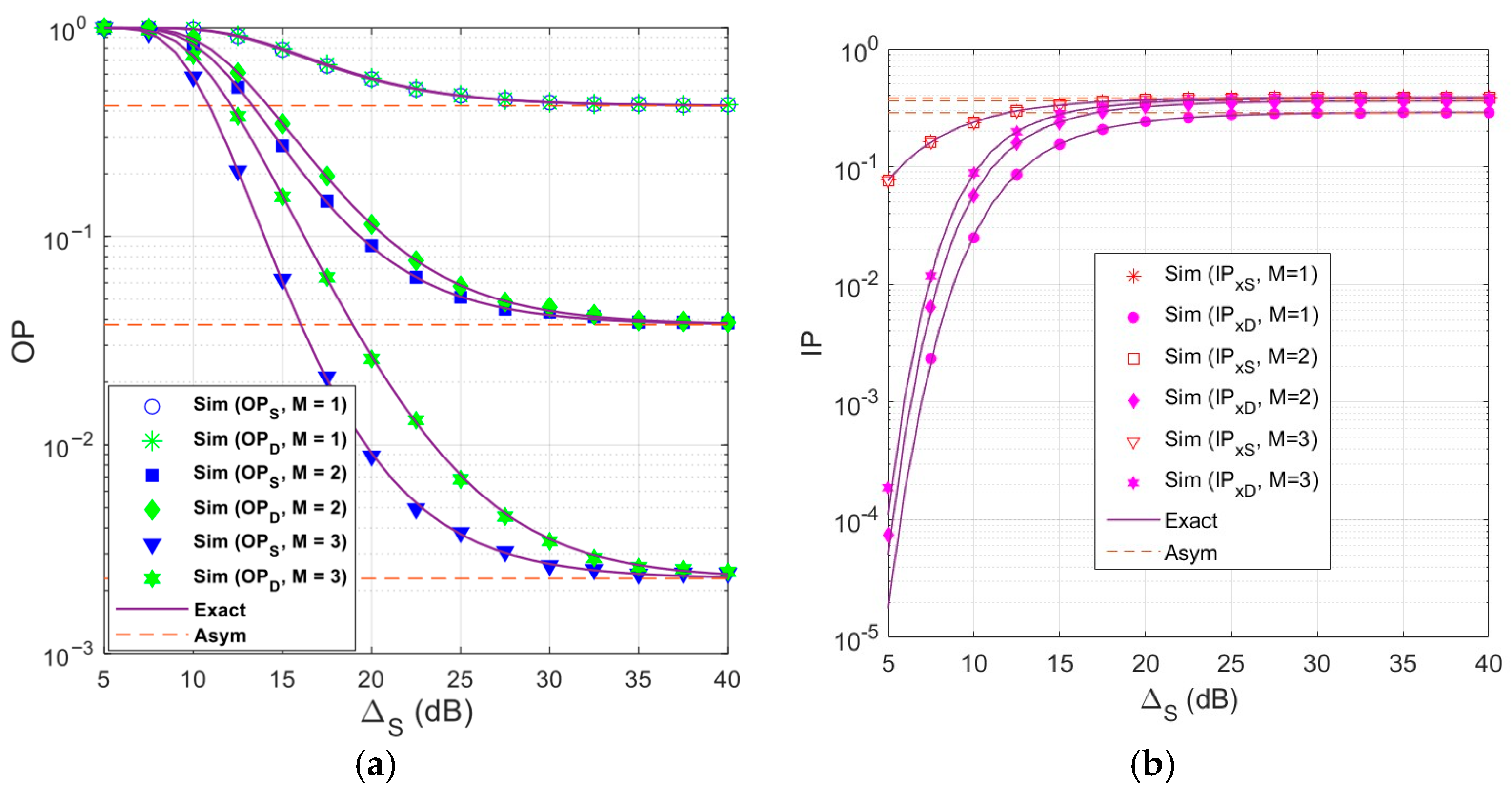

Figure 2 illustrates

(

Figure 2a) and

(

Figure 2b) as a function of

in dB with different number of relay stations

and with

. As observed in

Figure 2a,

at

and

decreases as

increases (or the transmit power of all the transmitters increases). However, at high

values, the values of

and

converge to the same outage floors, as proved in

Section 3. It is also seen that

at

is lower than that at

, and the

performance at both

and

improves substantially with increasing

. It is due to the fact that increasing

improves the probability that at least one relay station can successfully decode both

and

in the first phase, and it also enhances the channel quality of the

links. However, when

, the OP performance of S and D is quite identical because there is no relay selection at the second phase, and the system is hence symmetric for

and

. It is worth noting that the scheme with

corresponds to the random relay selection scheme. Hence,

Figure 2a shows that the proposed scheme achieves significantly better

performance than the random relay selection scheme.

In

Figure 2b, we can observe that

and

increase as

increases. As proved in

Section 3, we can see that

and

converge to statured values at high

regime. It is also seen from

Figure 2b that

is higher

, and

increases with the increasing of

. It is worth noting that

does not depend on the number of relays because

only decodes

directly from the satellite (See

Remark 3). On the other hand,

can decode

indirectly via the relay stations, so

depends on the number of relays. In particular, the more relays there are, the greater the opportunity that E will successfully decode

.

From

Figure 2a,b, we can see that the

results confirm the correction of the theoretical results. In addition, we can observe that there exists the trade-off between reliability and security. Indeed, as

increases, the

and

values decrease, but while the

and

values increase. Furthermore, the proposed scheme obtains better outage performance as increasing

; however, the

performance is worse with high value of

. Finally, we can see that

and

which means that the reliability of transmitting the data

is better than that of

, but the security of

is lower.

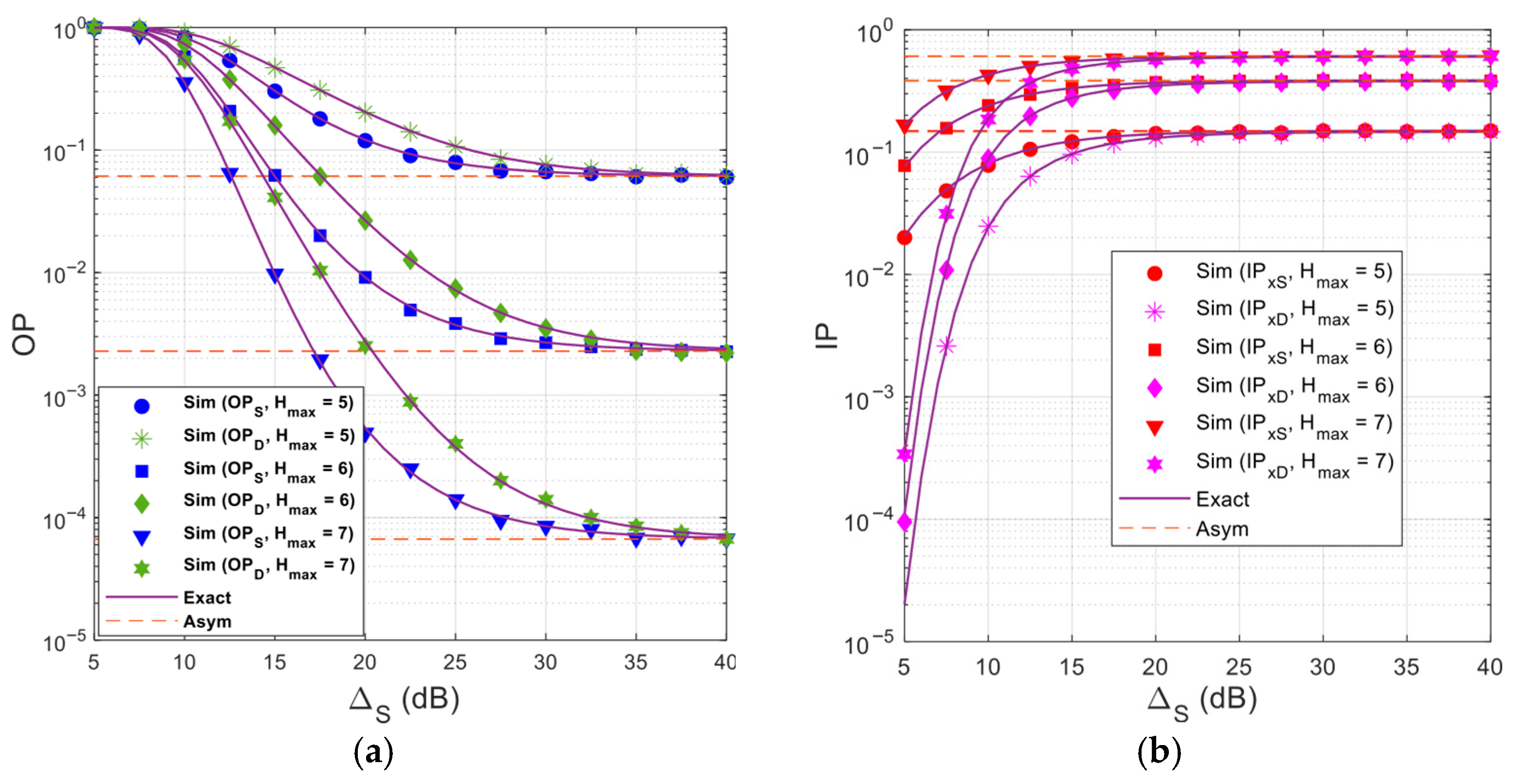

Figure 3 presents

(

Figure 3a) and

(

Figure 3b) as a function of

in dB with different values of

and with

. As presented in

Figure 3a,

at

and

significantly decreases as

increases. This is because increasing

raises the probability that

and

can receive enough

encoded packets

and

, respectively, thereby reducing outage probability at both

and

.

In contrast to

,

Figure 3b shows that the

values increase with increasing

, because a larger

also enhances the probability that the

node receives sufficiently the encoded packets.

From

Figure 3a,b, we can see that the

results again validate the theoretical results. We also observe that there exists the trade-off between

and

, as

changes from 5 to 7.

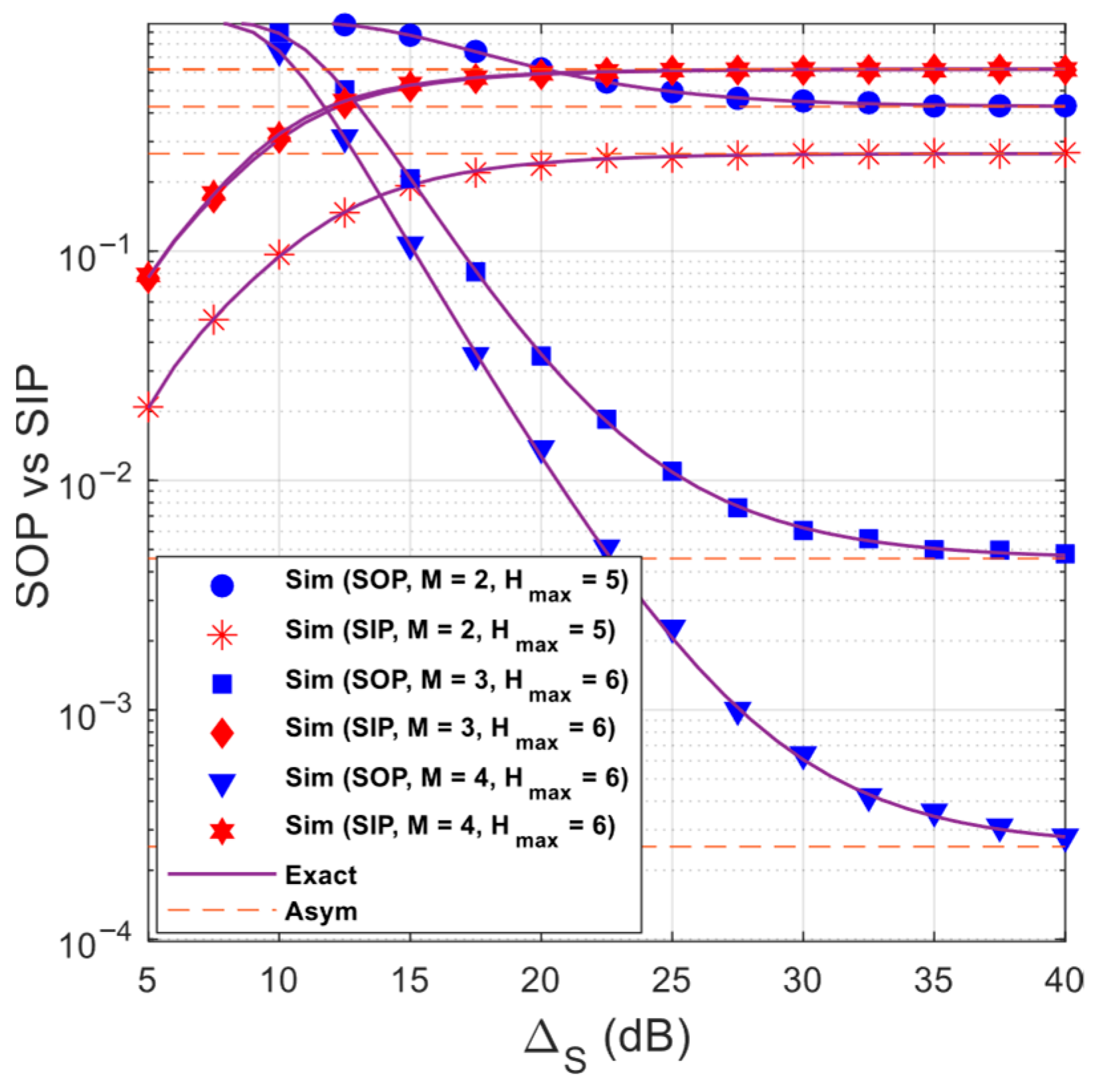

In

Figure 4, we present both

and

as a function of

in dB with various values of

and

. Since the IP and OP values converge to their saturated levels at high

values, the SIP and SOP values also converge to their saturated levels. Similarly to the

performance, the

performance also improves as

and

increase. Conversely, the SIP performance is worse as

and

increase. However, it is seen that the SIP values in the cases of

and

are quite similar. This means that, as

increases from 3 to 4, the SOP performance improves significantly, while the SIP performance changes only slightly.

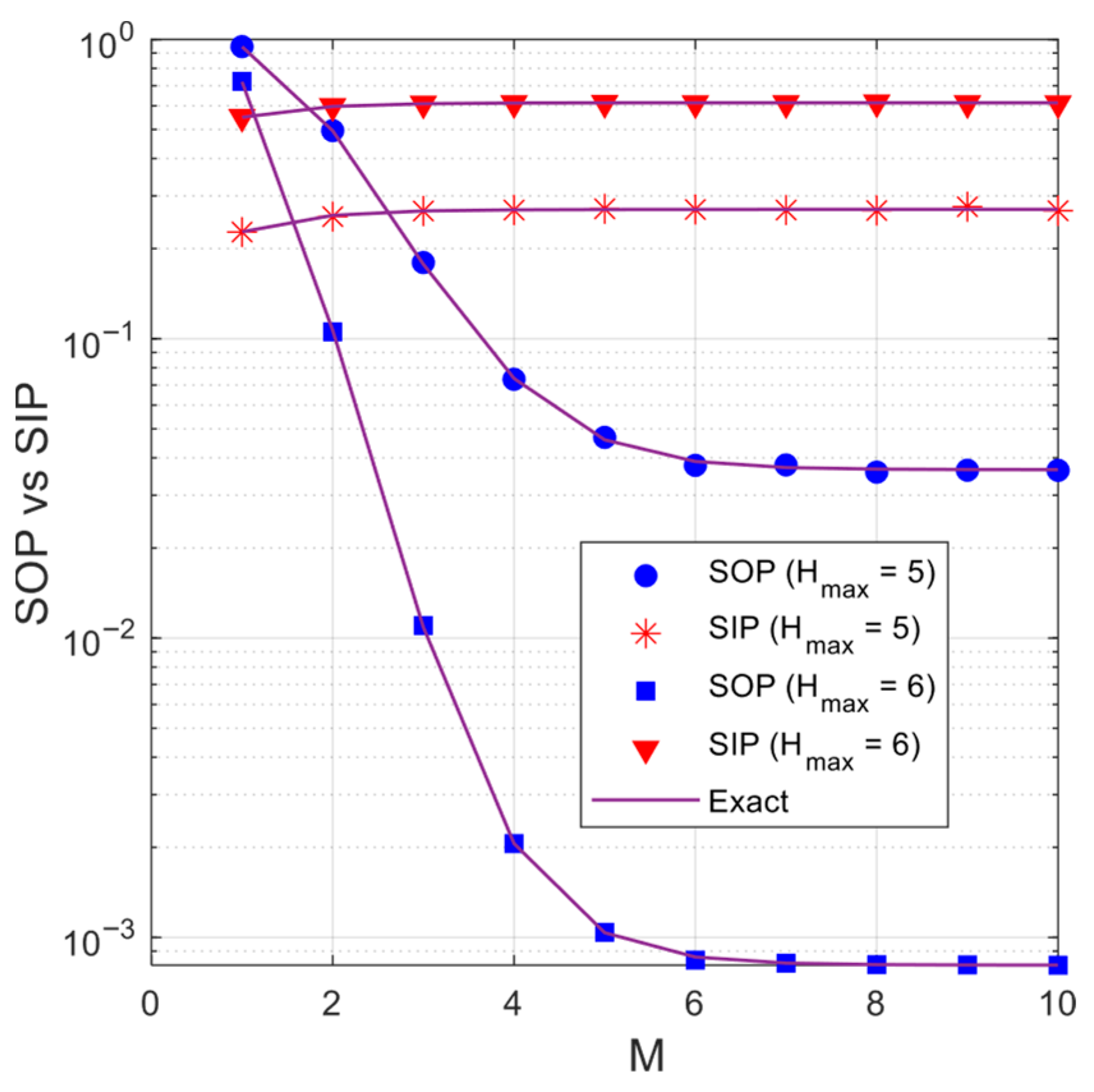

Figure 5 investigates the impact of the number of relay stations on the

and

performance with

(dB). As observed, the

values decrease rapidly as

increases. However, when

becomes sufficiently large, the

values no longer decrease. This behavior is due to the

method, i.e., at high

values, the quality of the

link is good, and hence, the quality of the

link dominates the

performance. For the

performance, we can see that the

values rapidly increase as

changes from 1 to 3. As

, the SIP performance varies only slightly, as also seen in

Figure 4 above. Similarly to

Figure 2a,b,

Figure 5 shows that the proposed scheme achieves significantly better

performance than the random relay selection scheme (

). In return, the proposed scheme incurs a slightly higher

.

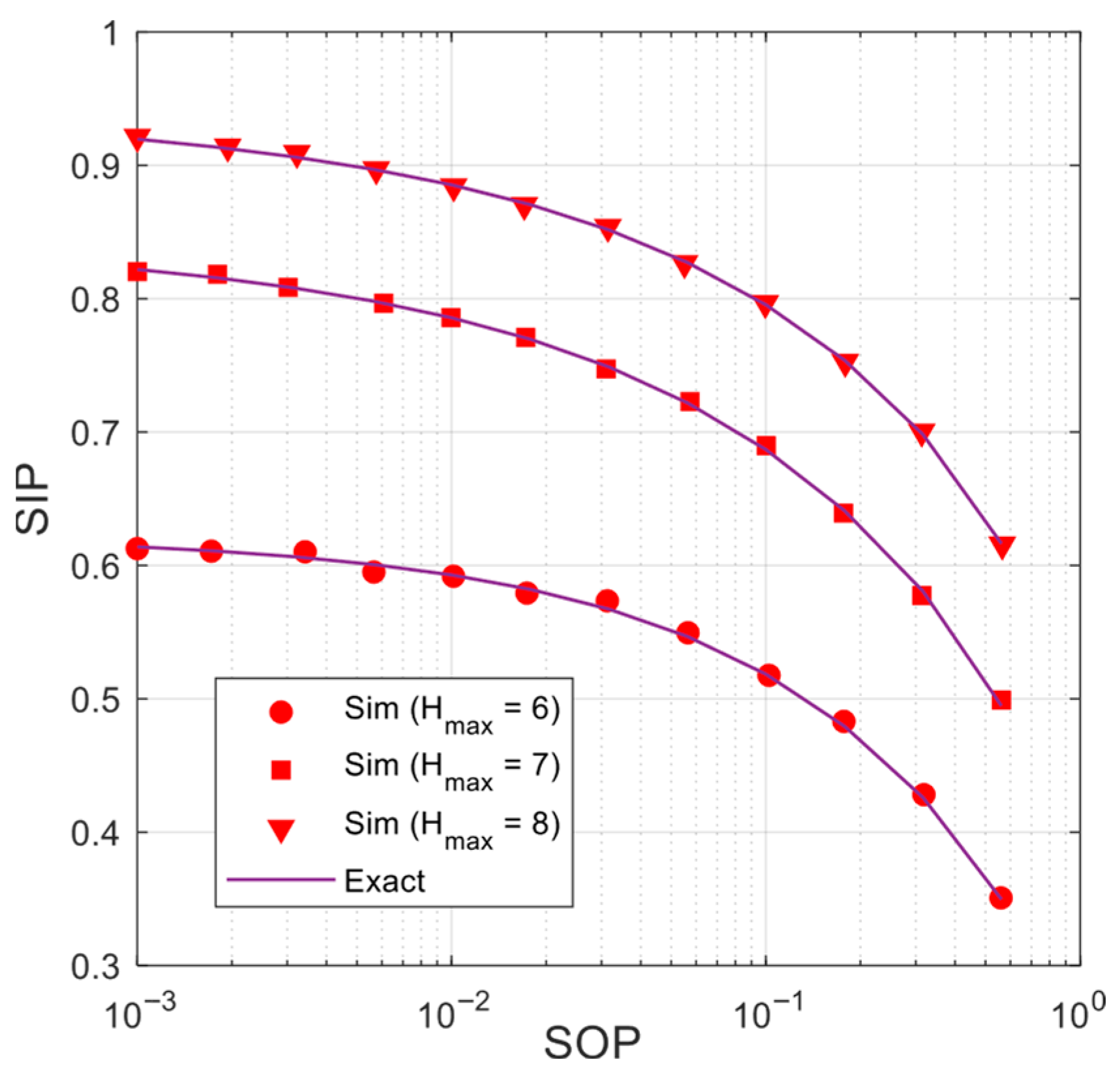

To more clearly analyze the impact of

and

on the security–reliability tradeoff,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 present

as a function of

. To realize this, we first determine the target

values, e.g.,

where

changes from

to

, as presented in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. Then, we use the

formula derived in

Section 3 to find the corresponding transmit power

. Next, we use the obtained values of

to calculate the corresponding values of

. Finally, we plot SIP as a function of SOP.

Figure 6 presents the trade-off between

and

with various values of

and with

. In particular, achieving better

performance in the proposed scheme comes at the cost of worse

performance. For example, with

, if the target

value is 0.1, then the

value is 0.6869. However, if the required SOP performance is 0.01 then the corresponding

performance is 0.7857.

Figure 6 also shows that increasing

decreases the trade-off between

and

. For example, with

, the value of

with

are 0.5185; 0.6869 and 0.7955, respectively.

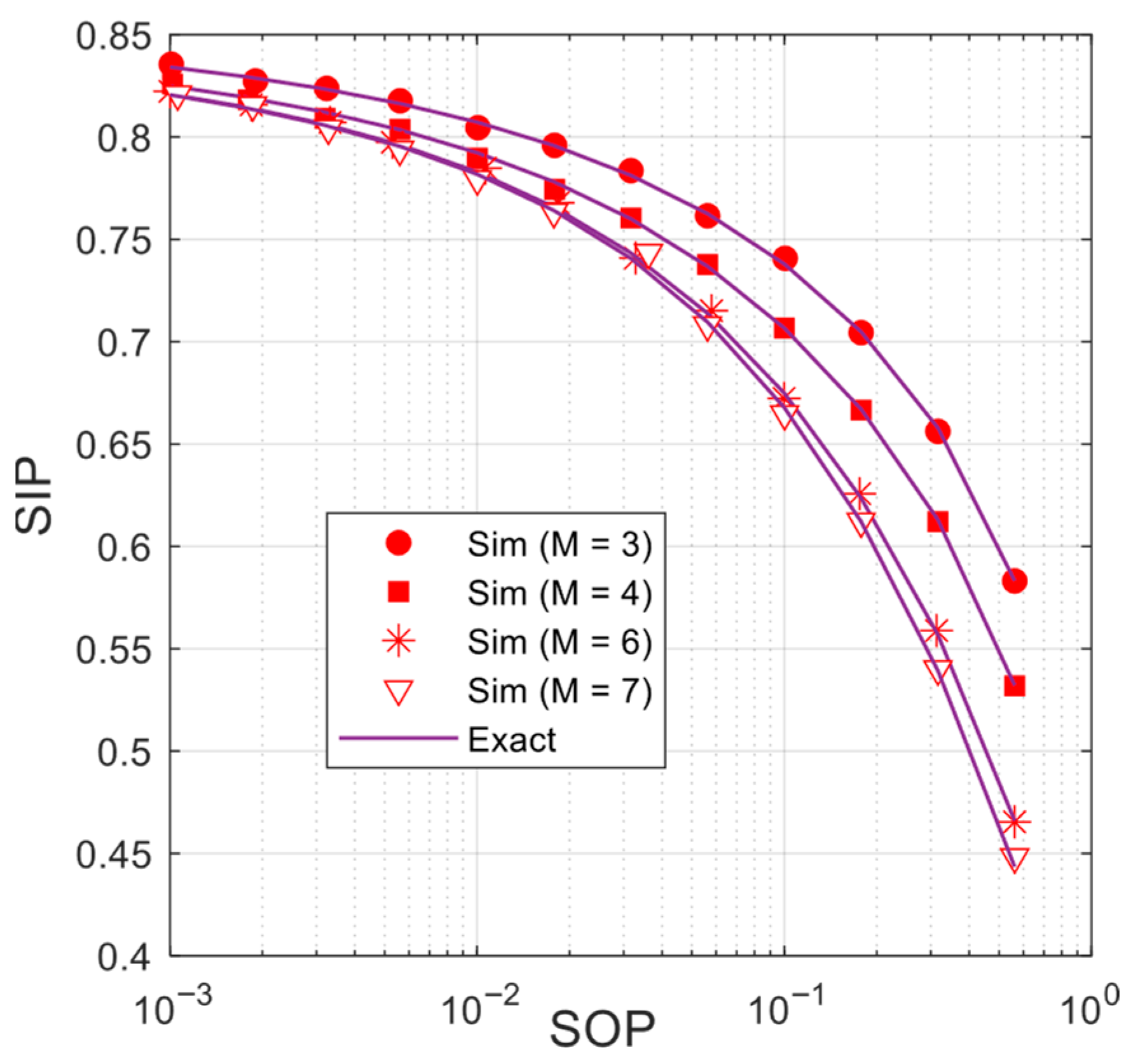

Figure 7 presents the trade-off between

and

with various values of

and with

. As we can observe, the trade-off between SOP and SIP is better as increasing

. However, as mentioned in

Figure 5, as

is high enough, both the

and

performance do not change any more. Indeed, as seen from

Figure 7, the SIP performance only changes slightly as

and

.