A Quantum MIMO-OFDM Framework with Transmit and Receive Diversity for High-Fidelity Image Transmission

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

- Development of a quantum MIMO-OFDM system that combines spatial and frequency diversity in the quantum domain for high-fidelity image transmission.

- 2.

- Design of a multi-qubit quantum encoding scheme integrated with quantum MIMO-OFDM modulation to enhance spectral efficiency and robustness.

- 3.

- Introduction of a robust QOFDM system using QFT and IQFT to effectively mitigate channel noise and fading in image transmission.

- 4.

- Empirical validation demonstrating significant improvements in image quality and transmission reliability over classical MIMO-OFDM systems under realistic fading channel conditions.

2. Related Work

2.1. Advantages of Quantum Communication

2.2. Efficient and Reliable Quantum Communication Systems

2.3. The Importance of MIMO Technology

2.4. The Importance of OFDM Technology

2.5. The Importance of MIMO-OFDM Technology

2.6. Research Gaps

- The development of quantum MIMO systems for spatial diversity in quantum domains is still in its infancy, with limited research exploring their potential to enhance multimedia transmission using only single-qubit encoding.

- QOFDM leveraging QFT has been theoretically proposed using only single-qubit encoding and without accounting for real-world quantum noise, but lacks practical investigation for high-fidelity image transmission.

- Existing studies primarily address bit-level quantum communication performance or security aspects, with minimal focus on the impact of quantum techniques on perceptual image quality metrics under realistic wireless channel conditions.

- No integrated framework currently combines quantum MIMO and QOFDM techniques to harness both spatial and frequency quantum diversity for robust and efficient image transmission.

- No existing approach has developed or demonstrated a scalable multi-qubit encoding scheme specifically tailored for media transmission, which is essential to fully exploit the advantages of quantum parallelism and fidelity in practical applications.

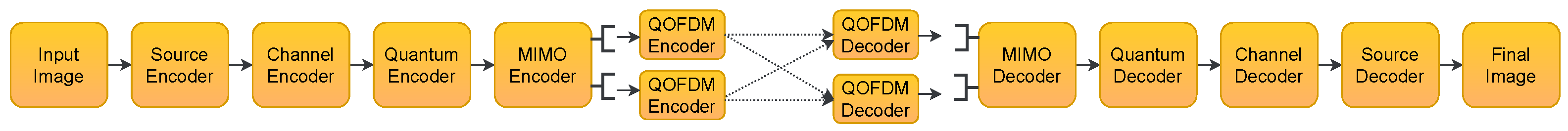

3. Proposed Framework

- Input Images: For evaluation, we use 100 images (256 × 192 pixels) from the Microsoft COCO dataset [65] and 20 high-resolution 4K images from the Kaggle dataset [66], ensuring diverse spatial information and detail levels. The framework supports a variety of image types, including grayscale and color, ensuring flexibility in various visual content regardless of the color format, resolution, or compression method.

- Source Encoder: This step compresses the image data using standard formats (e.g., JPEG, HEIF) or passes it through uncompressed, producing a classical bitstream. This stage evaluates the system’s adaptability to different compression standards and uncompressed data.

- Channel Encoder: Next, this bitstream is channel encoded using polar codes [67] with a code rate of 1/2 to improve robustness against channel impairments. Polar codes are selected because they are the first class of error-correcting codes that provably achieve the capacity of symmetric binary-input discrete memoryless channels with low encoding and decoding complexity. Their excellent performance at moderate code lengths and suitability for efficient hardware implementation make them highly advantageous compared to other classical error correction codes, such as the low-density parity check (LDPC) or Turbo codes. The code rate of 1/2 is chosen as a balanced trade-off between error correction capability and transmission efficiency, providing strong error resilience while maintaining reasonable data throughput.

- Quantum Encoder: The channel encoded bitstream is then segmented into bit blocks based on qubit encoding sizes ranging from 1 to 8. These bit blocks are subsequently quantum encoded into quantum superposition states using a multi-qubit encoding scheme, where each block of classical bits is mapped to a corresponding quantum state. Although the upper bound is not theoretically restricted and larger encodings are possible, the system limits the encoding to 8 qubits, as this is sufficient to represent the full range of pixel values (e.g., ) required for image transmission.

- MIMO Encoder: To exploit spatial diversity, the quantum encoded data are processed through a MIMO encoder in various antenna configurations, including SISO (1 × 1), MISO (2 × 1), and SIMO (1 × 2). The MIMO encoder distributes the quantum encoded symbols across multiple transmit antennas according to the chosen diversity scheme.

- QOFDM Encoder: Following the MIMO encoding stage, each transmit antenna applies an independent quantum-assisted OFDM modulation process. In this system, conventional inverse fast Fourier transform (IFFT) is replaced by the QFT, which operates on the quantum-encoded bitstream to generate orthogonal subcarriers in the quantum domain. Prior to this, the quantum encoded states were rearranged from serial to parallel form and input to the QFT. This transformation allows the data to be distributed across orthogonal quantum subcarriers, enabling efficient transmission in frequency-selective fading environments.

- Transmission: The resulting quantum subcarriers are then converted back to serial form, and a cyclic prefix is appended to each, which helps to mitigate ISI caused by multipath delay spread. Each processed stream is transmitted through the noisy quantum channel. In MIMO-OFDM systems, the channel is generally modeled to incorporate quantum noise effects along with frequency-selective fading, which reflects the multipath propagation characteristics across different subcarriers. Depending on the scenario, a flat fading model may be used for simplified simulations or narrowband cases, whereas frequency-selective fading models are applied in wideband and more realistic channel conditions.

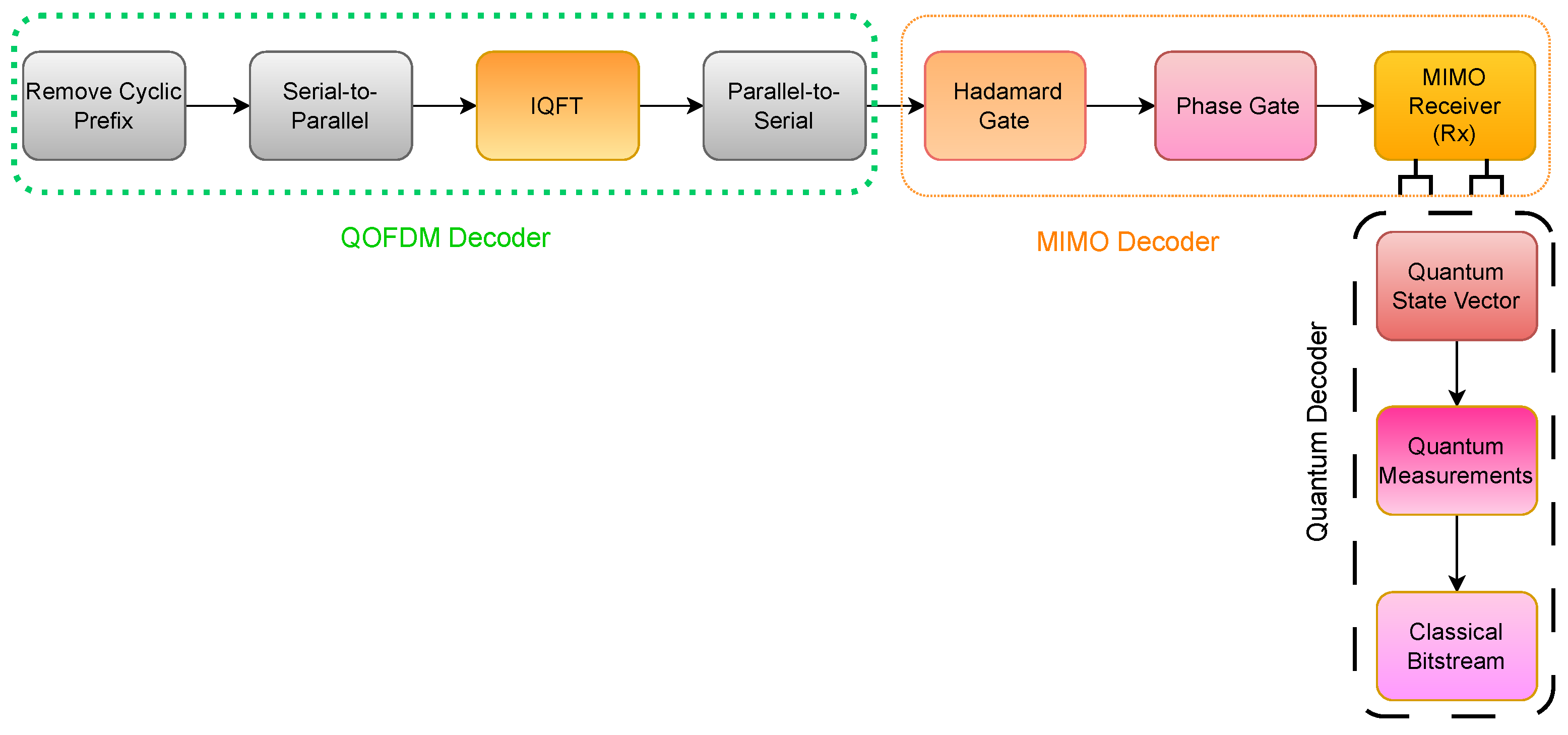

- QOFDM Decoder: First, the cyclic prefix is removed and the received signal is converted from serial to parallel. The IQFT is then applied to recover the time-domain quantum data from the frequency-domain quantum subcarriers.

- MIMO Decoder: MIMO decoding to extract the individual streams transmitted from the received signals.

- Quantum Decoder: After spatial separation, quantum decoding is performed to recover the classical bitstream from the quantum states.

- Channel Decoder: The bitstream is then passed through polar decoding (with a code rate of 1/2) to correct any errors introduced by the channel.

- Source Decoder: Finally, source decoding is performed according to the original format used during source encoding (e.g., JPEG or HEIF), or directly applied to uncompressed data if no compression was used, to reconstruct the transmitted images.

3.1. Proposed Quantum MIMO-OFDM Transmitter

3.1.1. Quantum Encoder

3.1.2. MIMO Encoder

- SISO (1 × 1, no diversity): A single quantum transmitter antenna sends the encoded quantum symbol to a single receiver antenna. This represents the baseline transmission scenario without spatial diversity.

- MISO (2 × 1, transmit diversity): Multiple transmitter antennas send the quantum symbol to a single receiver antenna. Transmit diversity schemes such as Alamouti coding [68] can be employed to exploit spatial diversity. For a 2-transmitter antenna system using the Alamouti code, the transmitted symbol matrix over two time slots can be represented as Equation (6).where and are quantum symbols transmitted from the two antennas. The received signals are combined at the receiver to recover and with improved robustness.

- SIMO (1 × 2, receive diversity): A single transmitter antenna sends the quantum symbol to multiple receiver antennas. The received signals are combined using maximal-ratio combining (MRC) to improve detection reliability.The received signal vector can be modeled as in Equation (7).where

- is the received signal vector with receiver antennas,

- is the channel vector representing the complex channel gains between the transmitter and each of the receiver antennas,

- r is the transmitted quantum symbol (scalar),

- is the noise vector.

The combined signal after MRC is given by Equation (8).where denotes the conjugate transpose (Hermitian transpose) of .

3.1.3. QOFDM Encoder

3.2. Quantum Channel

3.2.1. Intrinsic Quantum Noise

3.2.2. Layered Channel Representation

- Rayleigh fading: models amplitude and phase variations due to environmental propagation. This Rayleigh fading model effectively characterizes multipath propagation in urban environments. In our simulations, the urban Rayleigh channel is defined by four distinct path delays of , with corresponding path gains of . A Doppler shift of 100 Hz is included to account for the relative motion between the transmitter and receiver, capturing the time-varying nature of the wireless channel typical in urban scenarios.

- Quantum decoherence: models intrinsic quantum processes such as bit-flip, phase-flip, depolarizing, amplitude damping, and phase damping using Kraus operators.

3.3. Proposed Quantum MIMO-OFDM Receiver

3.3.1. QOFDM Decoder

3.3.2. MIMO Decoder

3.3.3. Quantum Decoder

3.3.4. Coherent Processing and Hardware Requirements

- Overview of the quantum hardware model: The overall receiver can be expressed as a sequence of unitary operators acting on the received quantum state , as shown in Equation (41).where represents the QFT, is the quantum MIMO operator, and is the quantum encoding operator. All transformations before measurement are strictly unitary to preserve coherence.

- Implementation of receiver stages: The cyclic prefix removal and serial-to-parallel conversion can be implemented as reversible data reordering operations using SWAP gates. Equivalently, these steps can be represented as a partial trace operation, as illustrated in Equation (42).Here, represents the remaining data qubits, and traces out the prefix qubits.Next, the IQFT maps frequency-domain superpositions to the computational basis and is implemented via Hadamard and controlled-phase gates, as shown in Equation (43).where is the Hadamard gate applied to qubit j and denotes a controlled-phase rotation between qubits j and k.The quantum MIMO decoder implements the inverse channel unitary , as shown in Equation (44), and acts on the quantum state following the application of the IQFT.This operation can be decomposed into standard gates (Hadamard, CNOT, and phase gates) to maintain full coherence.In the quantum OFDM-MIMO framework, all unitary operations, including cyclic prefix removal, IQFT, and MIMO decoding, are applied prior to any measurement. Measurement irreversibly collapses the quantum state; performing it earlier would destroy superposition and entanglement, making further processing impossible.The final projective measurement is performed on the fully processed state, as shown in Equation (45).where denotes the measurement superoperator. This procedure ensures that quantum collapse occurs only at the final stage, preserving superposition and enabling full exploitation of quantum parallelism and interference effects [13,44].

- CP removal/serial-to-parallel conversion: Reversible qubit reordering using SWAP gates or partial trace.

- IQFT: Implemented via cascaded Hadamard and controlled-phase rotations.

- MIMO decoding: Implemented as inverse unitary using standard quantum gates.

- Measurement: Standard projective measurement readout on qubits.

3.3.5. Classical MIMO-OFDM System

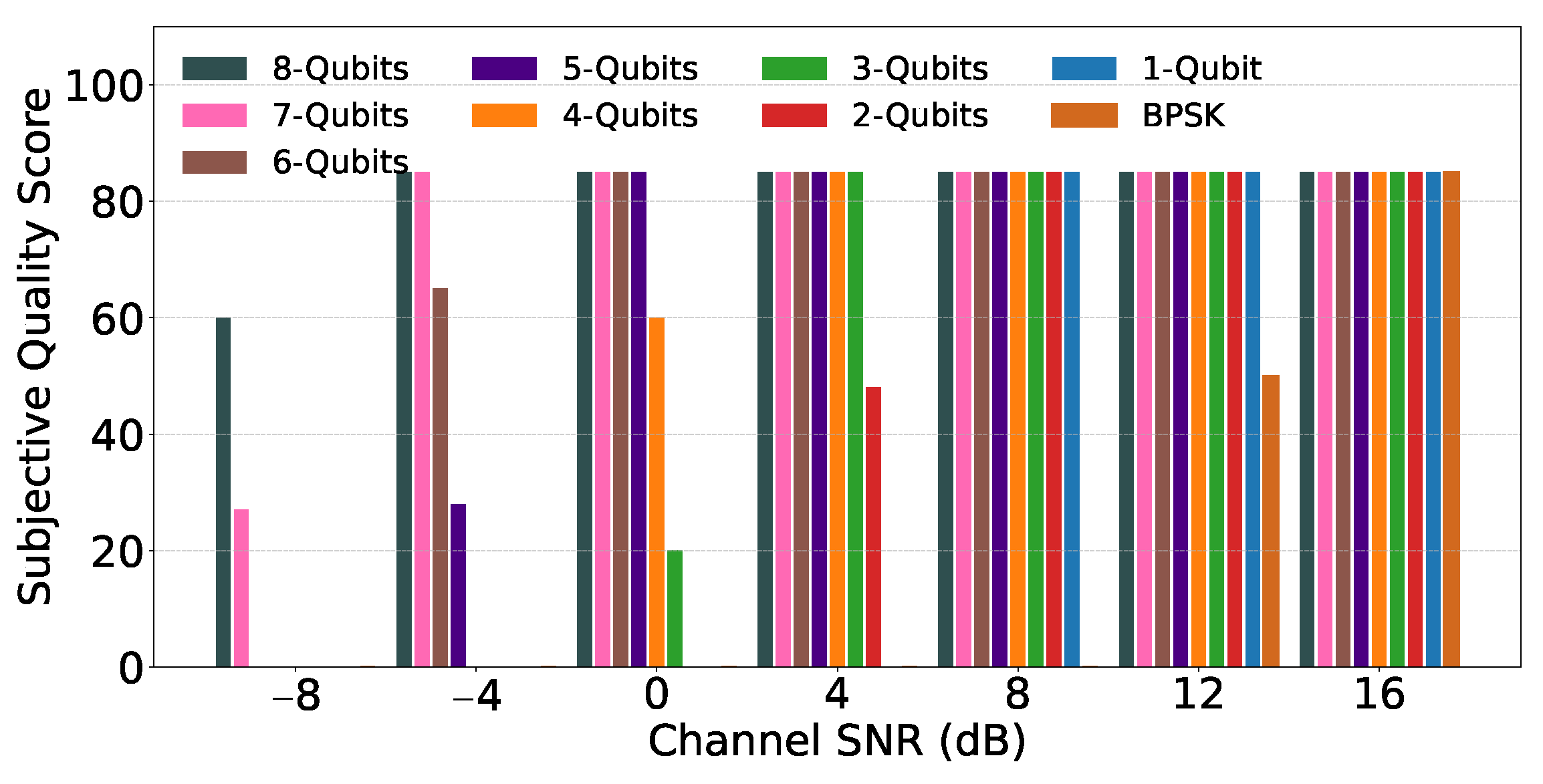

4. Results and Discussion

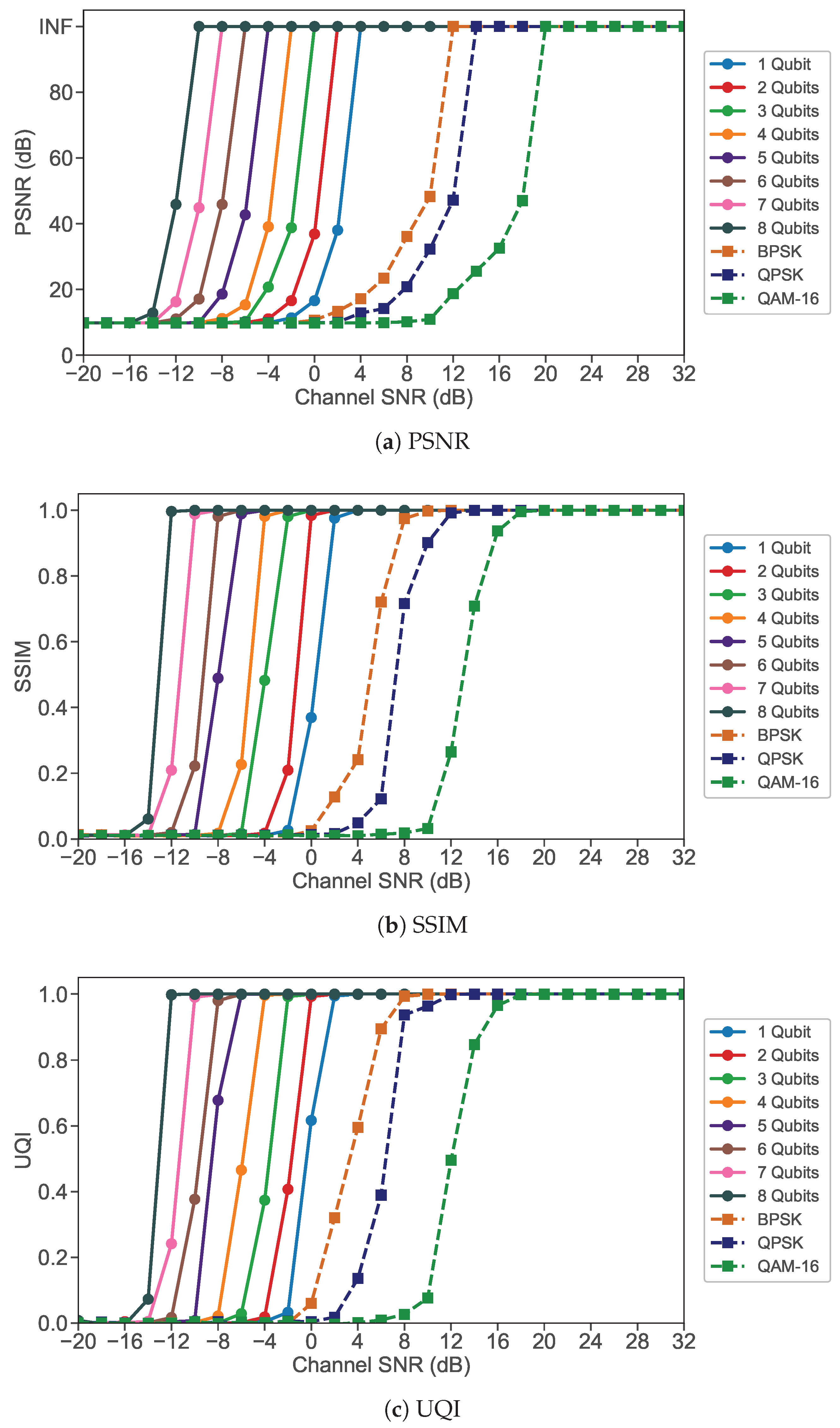

4.1. Performance Comparison of JPEG Image Transmission Using Quantum MIMO-OFDM and Classical MIMO-OFDM Systems

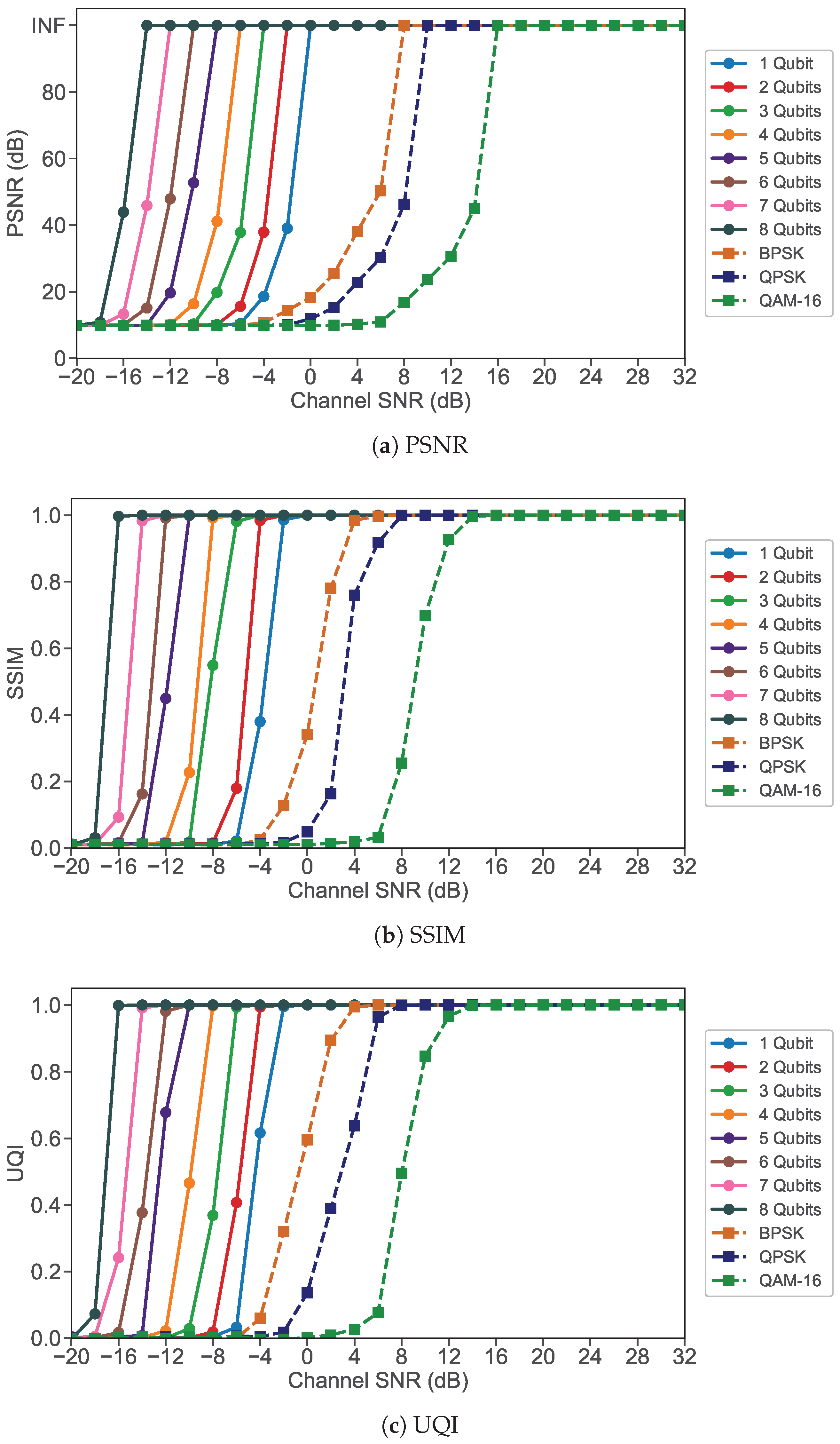

4.2. Performance Comparison of HEIF Image Transmission Using Quantum MIMO-OFDM and Classical MIMO-OFDM Systems

4.3. Performance Comparison of Uncompressed Image Transmission Using Quantum MIMO-OFDM and Classical MIMO-OFDM Systems

Mathematical Justification of 0 dB PAPR

4.4. Complexity Analysis

4.5. Scalability

4.6. Hardware Constraints and Practical Implementation

4.7. Potential Applications

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BPSK | Binary Phase-Shift Keying |

| CP | Cyclic Prefix |

| CSI | Channel State Information |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| HEIF | High Efficiency Image Format |

| ICI | Inter-Carrier Interference |

| IFFT | Inverse Fast Fourier Transform |

| IQFT | Inverse Quantum Fourier Transform |

| JPEG | Joint Photographic Experts Group |

| LDPC | Low-Density Parity-Check |

| MIMO | Multi-Input Multi-Output |

| MIMO-OFDM | Multi-Input Multi-Output Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing |

| MISO | Multi-Input Single-Output |

| MRC | Maximal-Ratio Combining |

| OFDM | Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing |

| PAPR | Peak-to-Average Power Ratio |

| PSNR | Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| QAM | Quadrature Amplitude Modulation |

| QEC | Quantum Error Correction |

| QFT | Quantum Fourier Transform |

| QKD | Quantum Key Distribution |

| QOFDM | Quantum Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing |

| QP | Quantization Parameters |

| QPSK | Quadrature Phase-Shift Keying |

| SI | Spatial Information |

| SISO | Single-Input Single-Output |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| SSIM | Structural Similarity Index Measure |

| UQI | Universal Quality Index |

References

- Coelho, H.; Monteiro, P.; Gonçalves, G.; Melo, M.; Bessa, M. Immersive Creation of Virtual Reality Training Experiences. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 85773–85782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, F.; Raza, R.; Khan, M.O.; Arif, M.; Alvi, A.; Alam, T. Augmented Reality and its Applications in Education: A Systematic Survey. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 143250–143271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.; Weaver, W. The Mathematical Theory of Communication; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, T.; Singh, J.; Sharma, A. Simulative analysis of Rayleigh and Rician fading channel model and its mitigation. In Proceedings of the 2017 8th International Conference on Computing, Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Delhi, India, 3–5 July 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, W.Q.; Edwards, D.J. Measured MIMO Capacity and Diversity Gain with Spatial and Polar Arrays in Ultrawideband Channels. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2007, 55, 2361–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, M.S.; Song, H.K. Cooperative diversity technique for MIMO-OFDM uplink in wireless interactive broadcasting. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2008, 54, 1627–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Guo, C.; Yang, Y.; Ni, W.; Quek, T.Q.S. OFDM-Based Digital Semantic Communication with Importance Awareness. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2024, 72, 6301–6315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.P.; Vetrithangam, D. A Thorough Assessment on Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing (OFDM) based Wireless Communication: Challenges and Interpretation. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Sustainable Computing and Smart Systems (ICSCSS), Coimbatore, India, 14–16 June 2023; pp. 1145–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Winters, J.; Sollenberger, N. MIMO-OFDM for wireless communications: Signal detection with enhanced channel estimation. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2002, 50, 1471–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Shen, A.; Hu, S.; Ni, W.; Wang, X.; Hossain, E. Towards Quantum-Native Communication Systems: State-of-the-Art, Trends, and Challenges. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, G.T.; Ashwini, P.; Tabassum, N. A Review on Quantum Communication and Computing. In Proceedings of the 2023 2nd International Conference on Applied Artificial Intelligence and Computing (ICAAIC), Salem, India, 4–6 May 2023; pp. 1592–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, W.Y.; Leong, Y.Z.; Leong, W.S. Quantum Consumer Technology: Advancements in Coherence, Error Correction, and Scalability. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Consumer Electronics-Taiwan (ICCE-Taiwan), Taichung, Taiwan, 9–11 July 2024; pp. 79–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, U.; Fernando, A. A Quantum OFDM Framework for High-Fidelity Image Transmission. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.S.; Loke, T.; Izaac, J.A.; Wang, J.B. Quantum Fourier transform in computational basis. Quantum Inf. Process. 2017, 16, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, U.; Samarathunga, P.; Ganearachchi, Y.; Fernando, T.; Fernando, A. Quantum communications for image transmission over error-prone channels. Electron. Lett. 2024, 60, e13300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, U.; Kushantha, N.; Fernando, T.; Fernando, A. A Robust Multi-Qubit Quantum Communication System for Image Transmission over Error Prone Channels. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2025, 71, 7551–7558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.R.; Chowdhury, M.Z.; Sayem, M.; Jang, Y.M. Quantum Communication Systems: Vision, Protocols, Applications, and Challenges. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 15855–15877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafique, M.A.; Munir, A.; Latif, I. Quantum Computing: Circuits, Algorithms, and Applications. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 22296–22314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballentine, L.E. Quantum Mechanics: A Modern Development, 2nd ed.; World Scientific Publishing Company: Singapore, 2014; p. 740. [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand, B.; Ghimire, A.; Amsaad, F.; Razaque, A.; Mohanty, S.P. Quantum communication networks: Design, reliability, and security. IEEE Potentials 2025, 44, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Chen, N.; Shen, S.; Yu, S.; Wu, S.; Kumar, N. Future Quantum Communications and Networking: A Review and Vision. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2024, 31, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzalini, A. Quantum Communications in Future Networks and Services. Quantum Rep. 2020, 2, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.Z.; Abohmra, A.; Usman, M.; Zahid, A.; Heidari, H.; Imran, M.A.; Abbasi, Q.H. Quantum for 6G communication: A perspective. IET Quantum Commun. 2023, 4, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwer, S.; Younes, A.; Elkabani, I.; Elsayed, A. Preparation of Quantum Superposition Using Partial Negation. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 18944–18954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, N. Quantum Entanglement and Its Application in Quantum Communication. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1827, 012120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, M. Quantum Key Distribution and Its Applications. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2018, 16, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, S.; Pan, W. Quantum Image Compression: Fundamentals, Algorithms, and Advances. Computers 2024, 13, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Fu, X.; Sun, L.; Muhammad, G. QDICP: A Quantum Blockchain Model for Copyright Protection of Digital Images in Consumer Electronics. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024, 71, 5189–5200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, B.; Parida, P.; Nayak, C.; Khalifa, T.; Kumar Panda, M.; Ali, N.; Uttam Patil, G.; Prasad, B. Multi-Channel Multi-Protocol Quantum Key Distribution System for Secure Image Transmission in Healthcare. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 62476–62505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariprasad, Y.; Iyengar, S.; Chaudhary, N.K. Securing the Future: Advanced Encryption for Quantum-Safe Video Transmission. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024, 71, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janani, T.; Brindha, M. A secure medical image transmission scheme aided by quantum representation. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2021, 59, 102832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guérin, P.A.; Feix, A.; Araújo, M.; Brukner, Č. Exponential Communication Complexity Advantage from Quantum Superposition of the Direction of Communication. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 117, 100502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feix, A.; Araújo, M.; Brukner, Č. Quantum superposition of the order of parties as a communication resource. Phys. Rev. A 2015, 92, 052326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, K.; Cao, Y.; Paz-Silva, G.A.; Romero, J.; White, A.G. Increasing communication capacity via superposition of order. Phys. Rev. Res. 2020, 2, 033292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, U.; Samarathunga, P.; Pollwaththage, N.; Ganearachchi, Y.; Fernando, T.; Fernando, A. Quantum Communication for Video Transmission Over Error-Prone Channels. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2025, 71, 1148–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, U.; Pollwaththage, N.; Ganearachchi, Y.; Samarathunga, P.; Fernando, T.; Fernando, A. Quantum Communication based Image Transmission over Error-Prone Channels with Three-Qubit Stabilizer Code. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 11–14 January 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, U.; Fernando, T.; Fernando, A. High-Fidelity Image Transmission in Quantum Communication with Frequency Domain Multi-Qubit Techniques. Algorithms 2025, 18, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Png, L.C.; Xiao, L.; Yeo, K.S.; Wong, T.S.; Guan, Y.L. MIMO-diversity switching techniques for digital transmission in visible light communication. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), Split, Croatia, 7–10 July 2013; pp. 000576–000582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.A.; Zhang, J.H.; Hsu, C.C.; Yang, C.W.; Lin, C.W. Design of High Isolation Slotted 2×2 MIMO Antenna for LTE and Sub-6G Applications. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Workshop on Electromagnetics: Applications and Student Innovation Competition (iWEM), Taoyuan, Taiwan, 10–12 July 2024; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, H.; Jafri, M.R.; Khan, A.U.; Lee, K.; Shin, H. An Efficient and Low-Profile MIMO Antenna for 5G-WiFi Interference Rejection: Design and Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2024 15th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology Convergence (ICTC), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 16–18 October 2024; pp. 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, N.K.; Dash, S.P.; McKay, M.R.; Mallik, R.K. MIMO Terahertz Quantum Key Distribution. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2021, 25, 3345–3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Pirandola, S.; Delfanazari, K. Millimeter-Waves to Terahertz SISO and MIMO Continuous Variable Quantum Key Distribution. IEEE Trans. Quantum Eng. 2023, 4, 4100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, J.U.; Rizvi, S.M.A.; Koudia, S.; Chatzinotas, S.; Shin, H. MIMO Quantum Communication in Correlated Pure-Loss Channels. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2025, 29, 1544–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, U.; Fernando, T.; Ganearachchi, Y.; Samarathunga, P.; Fernando, A. Quantum Communication Based Image Transmission with Transmit and Receive Diversity in MIMO Communication Systems. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2025, 71, 2500–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, U.; Samarathunga, P.; Fernando, T.; Fernando, A. Transmit and Receive Diversity in MIMO Quantum Communication for High-Fidelity Video Transmission. Algorithms 2025, 18, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasher, S.; Kumar, S. Effects of Various Digital Modulation Methods on LTE System Over Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexed AWGN: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication and Materials (ICACCM), Dehradun, India, 10–11 November 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffariahrar, E.; Theoleyre, F.; Menth, M. A Survey of Wi-Fi 6: Technologies, Advances, and Challenges. Future Internet 2022, 14, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Song, Y.; Owens, T.; Cosmas, J.; Itagaki, T. Performance analysis of the OFDM scheme in DVB-T. In Proceedings of the IEEE 6th Circuits and Systems Symposium on Emerging Technologies: Frontiers of Mobile and Wireless Communication (IEEE Cat. No.04EX710), Shanghai, China, 31 May–2 June 2004; Volume 2, pp. 489–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, M.; Banawan, M.; Arya, V.; Mishra, S.K. Investigation of OFDM-Based HS-PON Using Front-End LiFi System for 5G Networks. Photonics 2023, 10, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameel, A.S.M.M.; Malhotra, A.; Gamal, A.E.; Hamidi-Rad, S. Deep OFDM Channel Estimation: Capturing Frequency Recurrence. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2024, 28, 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K. Design and Performance Analysis of OFDM Systems in 5G Networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Sensors, Electronics and Computer Engineering (ICSECE), Jinzhou, China, 29–31 August 2024; pp. 1840–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.P.; Wang, C.; Wang, Q.; Wu, M.; Wu, Y.; Yang, X. OFDM Receiver Design With Learning-Driven Automatic Modulation Recognition. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Commun. Netw. 2024, 10, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.W.; Kim, J.H.; Yoon, J.S.; Song, H.K. Cooperative OFDM system for high throughput in wireless personal area networks. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2010, 56, 458–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, M.R.; Ludwig, S. Application of HFrFT-OFDM to IEEE 802.11bd Performance Enhancement for Vehicle-to-vehicle Communication in High Speed Conditions. In Proceedings of the 2024 20th International Conference on the Design of Reliable Communication Networks (DRCN), Montreal, QC, Canada, 6–9 May 2024; pp. 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, L.; Peng, C.; Zhang, S.; Cui, Y.; Ma, C. A Robust Time-Frequency Synchronization Method for Underwater Acoustic OFDM Communication Systems. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 21908–21920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Shao, Y.; Mikolajczyk, K.; Gündüz, D. Channel-Adaptive Wireless Image Transmission With OFDM. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2022, 11, 2400–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, M.F.A.; Latiff, N.M.A.; Yusof, S.K.S.; Rashid, R.A.; Malik, N.N.N.A.; Yusof, K.M. Video transmission based on Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing (OFDM) utilizing television white space. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 13th Malaysia International Conference on Communications (MICC), Johor Bahru, Malaysia, 28–30 November 2017; pp. 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaawi, A.; Almasaoodi, M.; Imre, S. Exploiting OFDM method for quantum communication. Quantum Inf. Process. 2024, 23, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasaoodi, M.R.; Sabaawi, A.M.A.; Imre, S. Quantum OFDM: A Novel Approach to Qubit Error Minimization. In Proceedings of the 2024 14th International Symposium on Communication Systems, Networks and Digital Signal Processing (CSNDSP), Rome, Italy, 17–19 July 2024; pp. 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaawi, A.M.A.; Almasaoodi, M.R.; Imre, S. Advancing Quantum Communications: Q-OFDM with Quantum Fourier Transforms for Enhanced Signal Integrity. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Software, Telecommunications and Computer Networks (SoftCOM), Split, Croatia, 26–28 September 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkat, H.; Monteiro, P.; Gameiro, A.; Guiomar, F.; Ahmed, F.T. A Survey on MIMO-OFDM Systems: Review of Recent Trends. Signals 2022, 3, 359–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.W. A Low-Complexity MIMO-OFDM Transmission Scheme for Optical Wireless Communications. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 94777–94784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazgan, M.; Arslan, H.; Vakalis, S. MIMO-OFDM Imaging Using Shared Time and Bandwidth. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2025, 6, 4885–4893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakavi, M.J.; Nezamalhosseini, S.A.; Chen, L.R. Multiuser Massive MIMO-OFDM for Visible Light Communication Systems. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 2259–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2014; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Fleet, D., Pajdla, T., Schiele, B., Tuytelaars, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 8693, pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaggle Contributor. Images 4K. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/evgeniumakov/images4k (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Pathak, P.; Bhatia, R. Performance Analysis of Polar codes for Next Generation 5G Technology. In Proceedings of the 2022 3rd International Conference for Emerging Technology (INCET), Belgaum, India, 27–29 May 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamouti, S. A simple transmit diversity technique for wireless communications. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 1998, 16, 1451–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.A.; Chuang, I.L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information: 10th Anniversary Edition; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z.; Zhang, W. The Simulation Models for Rayleigh Fading Channels. In Proceedings of the 2007 Second International Conference on Communications and Networking in China, Shanghai, China, 22–24 August 2007; pp. 1158–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Shapiro, J.H. Quantum illumination for enhanced detection of Rayleigh-fading targets. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 96, 020302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horé, A.; Ziou, D. Is there a relationship between peak-signal-to-noise ratio and structural similarity index measure? IET Image Process. 2013, 7, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bovik, A. A universal image quality index. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2002, 9, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Telecommunication Union (ITU). Methodologies for the Subjective Assessment of the Quality of Television Pictures; ITU-R Recommendation BT.500; International Telecommunication Union: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, V.S.; Kumar, A.; Das, J.; Dev, K.; Magarini, M. Quantum Error Correction Codes in Consumer Technology: Modeling and Analysis. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024, 70, 7102–7111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, U.; Samarathunga, P.; Fernando, T.; Ganearachchi, Y.; Fernando, A. Image Transmission Over Quantum Communication Systems with Three-Qubit Error Correction. Electron. Lett. 2025, 61, e70205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Image Format | Maximum Channel SNR Gains | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Qubit | 2 Qubits | 3 Qubits | 4 Qubits | 5 Qubits | 6 Qubits | 7 Qubits | 8 Qubits | |

| JPEG () | 8 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 18 | 20 | 22 |

| HEIF () | 8 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 18 | 20 | 22 |

| Uncompressed () | 8 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 18 | 20 | 22 |

| 4K | 8 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 18 | 20 | 22 |

| n (Qubits) | QFT Gates | Circuit Depth |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 3 | 2 |

| 3 | 6 | 3 |

| 4 | 10 | 4 |

| 5 | 15 | 5 |

| 6 | 21 | 6 |

| 7 | 28 | 7 |

| 8 | 36 | 8 |

| n (Qubits) | State-Vector Size () | Memory (KB) | Estimated FLOPs | Runtime @ 50 GFLOPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 0.03 | 2 | s |

| 2 | 4 | 0.06 | 12 | s |

| 3 | 8 | 0.13 | 48 | s |

| 4 | 16 | 0.25 | 160 | s |

| 5 | 32 | 0.50 | 480 | s |

| 6 | 64 | 1.00 | 1344 | s |

| 7 | 128 | 2.00 | 3584 | s |

| 8 | 256 | 4.00 | 9216 | s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jayasinghe, U.; Fernando, T.; Fernando, A. A Quantum MIMO-OFDM Framework with Transmit and Receive Diversity for High-Fidelity Image Transmission. Telecom 2025, 6, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/telecom6040096

Jayasinghe U, Fernando T, Fernando A. A Quantum MIMO-OFDM Framework with Transmit and Receive Diversity for High-Fidelity Image Transmission. Telecom. 2025; 6(4):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/telecom6040096

Chicago/Turabian StyleJayasinghe, Udara, Thanuj Fernando, and Anil Fernando. 2025. "A Quantum MIMO-OFDM Framework with Transmit and Receive Diversity for High-Fidelity Image Transmission" Telecom 6, no. 4: 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/telecom6040096

APA StyleJayasinghe, U., Fernando, T., & Fernando, A. (2025). A Quantum MIMO-OFDM Framework with Transmit and Receive Diversity for High-Fidelity Image Transmission. Telecom, 6(4), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/telecom6040096