Characterization, Kinetic Studies, and Thermodynamic Analysis of Pili (Canarium ovatum Engl.) Nutshell for Assessing Its Biofuel Potential and Bioenergy Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Preparation

2.2. Characterization of the Biomass

2.2.1. Proximate Analysis

2.2.2. Ultimate Analysis

2.2.3. Compositional Analysis

2.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

2.4. Kinetic Study

2.4.1. Model Fitting Method Using Coats Redfern

Reaction Mechanism Models Used

2.4.2. Model Free Method

The FWO Method

The KAS Method

The Starink Method

The Friedman Method

2.5. Thermodynamic Parameter Calculations

3. Results and Discussion

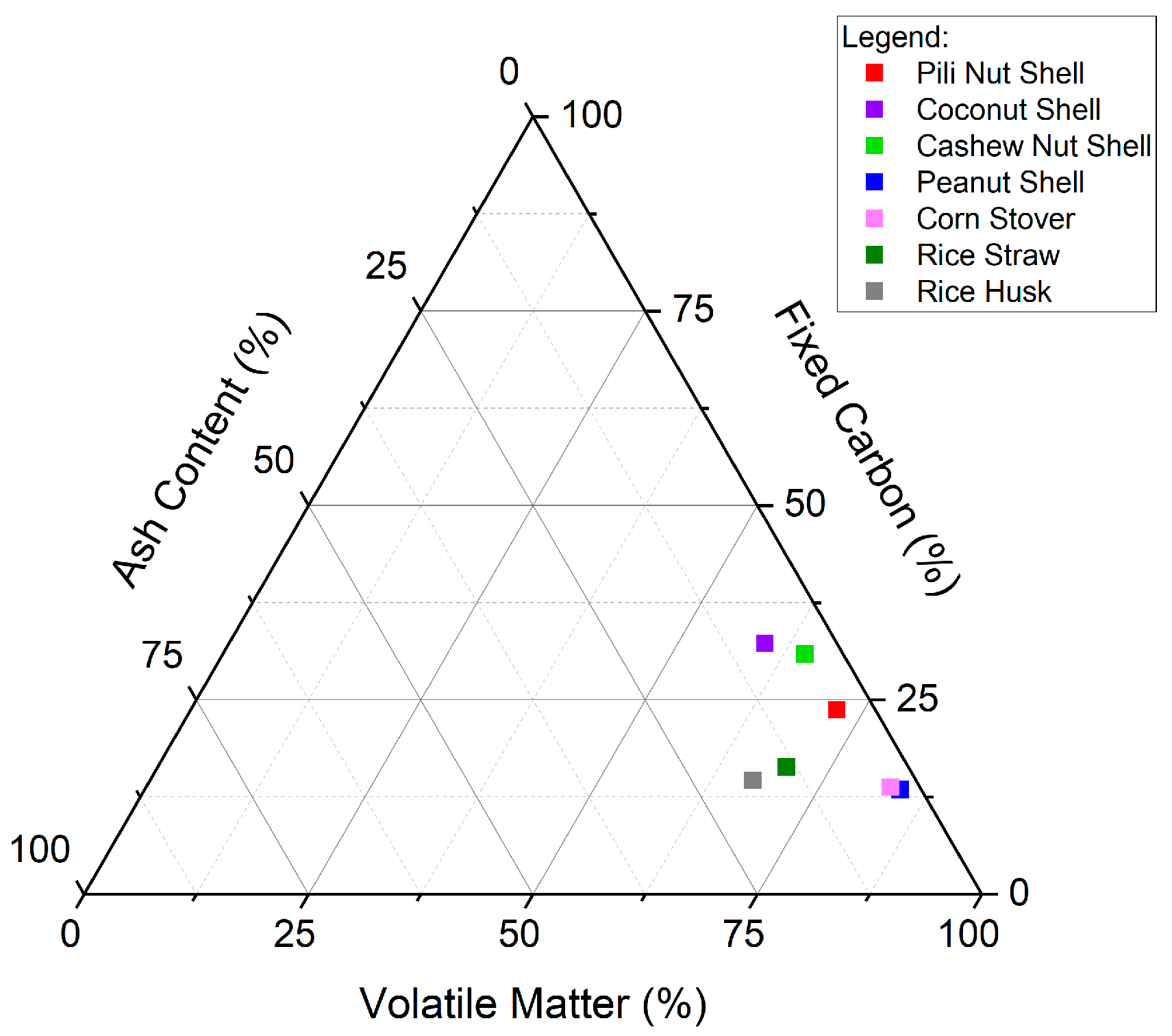

3.1. Thermochemical Properties

| Parameter | PS (This study) | CNS [21] | CS [33] | PNS [8] | CRS [36] | RS [35] | RH [9] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proximate Analysis | |||||||

| * MC, % | 8.32 ± 0.73 | 6.9 ± 0.07 | 6.93 | 6.32 ± 0.01 | 3.12 ± 0.06 | 5.7 | 4.15 |

| ** VMC, % | 72.00 ± 0.20 | 49.9 ± 0.48 | 76.81 | 78.84 ± 0.40 | 80.44 ± 0.47 | 66.1 | 64.43 |

| ** AC, % | 4.33 ± 0.76 | 6.7 ± 0.05 | 5.02 | 2.20 ± 0.40 | 3.17 ± 0.07 | 12.8 | 17.44 |

| ** FC, % | 23.67 ± 2.75 | 36.5 ± 0.35 | 18.17 | 12.57 ± 0.33 | 13.28 ± 0.61 | 15.4 | 13.98 |

| HHV, MJ/kg | 20.60 ± 0.04 | 17.40 | 20.16 | 19.69 ± 0.06 | 17.34 ± 0.04 | 12.1 | 15.97 |

| Ultimate Analysis | |||||||

| Carbon, % | 50.65 ± 0.60 | 41.8 ± 0.65 | 45.7 | 49 ± 10 | 45.69 ± 0.07 | 37.1 | 40.12 |

| Hydrogen, % | 6.46 ± 0.04 | 4.1 ± 0.08 | 3.7 | 7.9 ± 1.6 | 5.31 ± 0 | 5.2 | 5.11 |

| Oxygen, % | 39.52 ± 0.47 | 51.5 ± 0.51 | 44.6 | 39.6 ± 7.9 | 47.96 ± 0.1 | 44.3 | 54.14 |

| Nitrogen, % | 0.44 ± 0.08 | 2.1 ± 0.01 | 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 0.49 ± 0 | 0.5 | 0.53 |

| Sulfur, % | 1.16 ± 0.18 | 0.5 ± 0.01 | – | 0.083 ± 0.017 | 0.55 ± 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

3.2. Chemical Compositional Properties

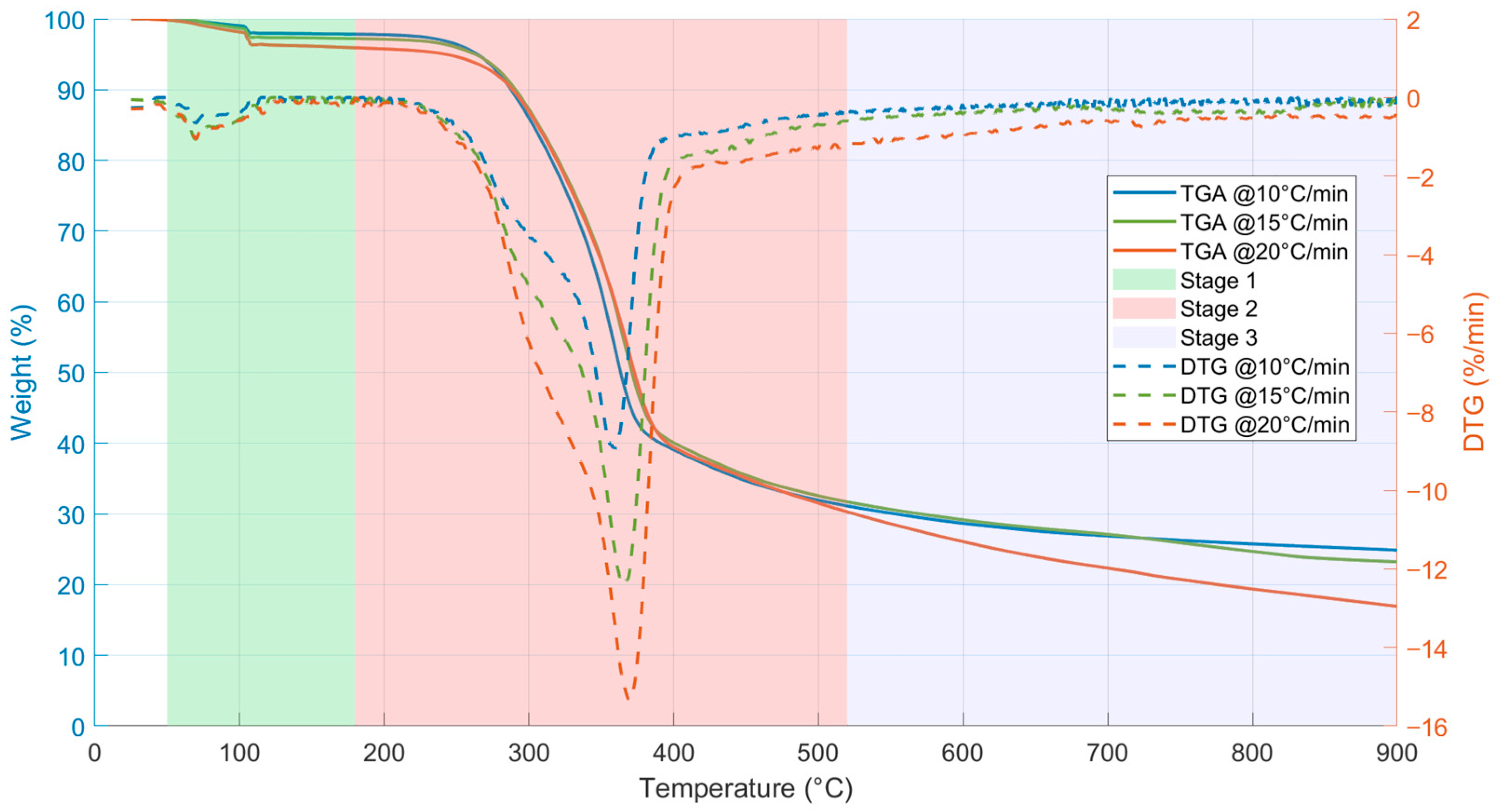

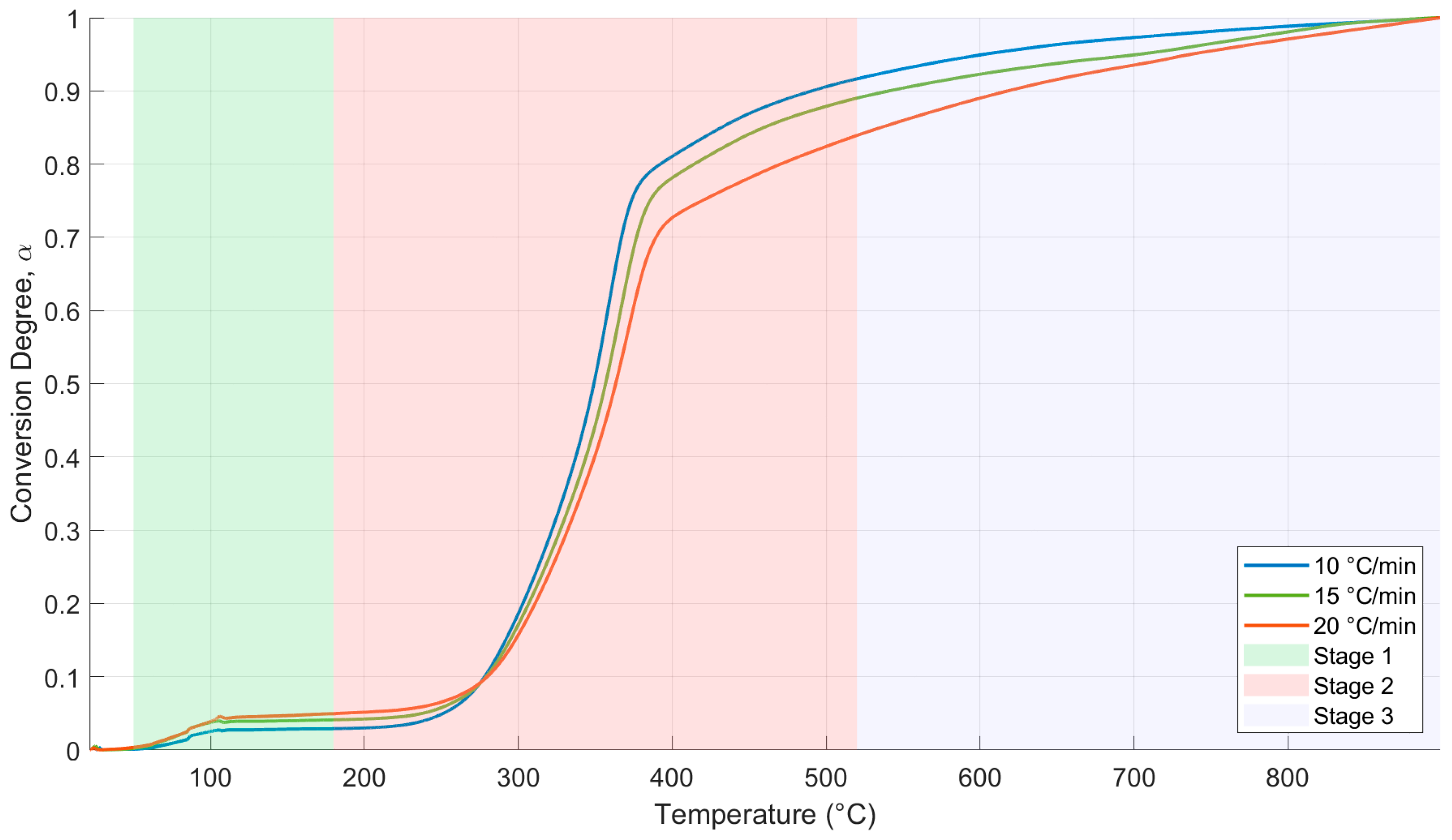

3.3. TGA/DTG Analysis and Thermal Decomposition Parameters

3.4. Kinetic Parameters and Reaction Mechanism

3.4.1. Coats-Redfern Method

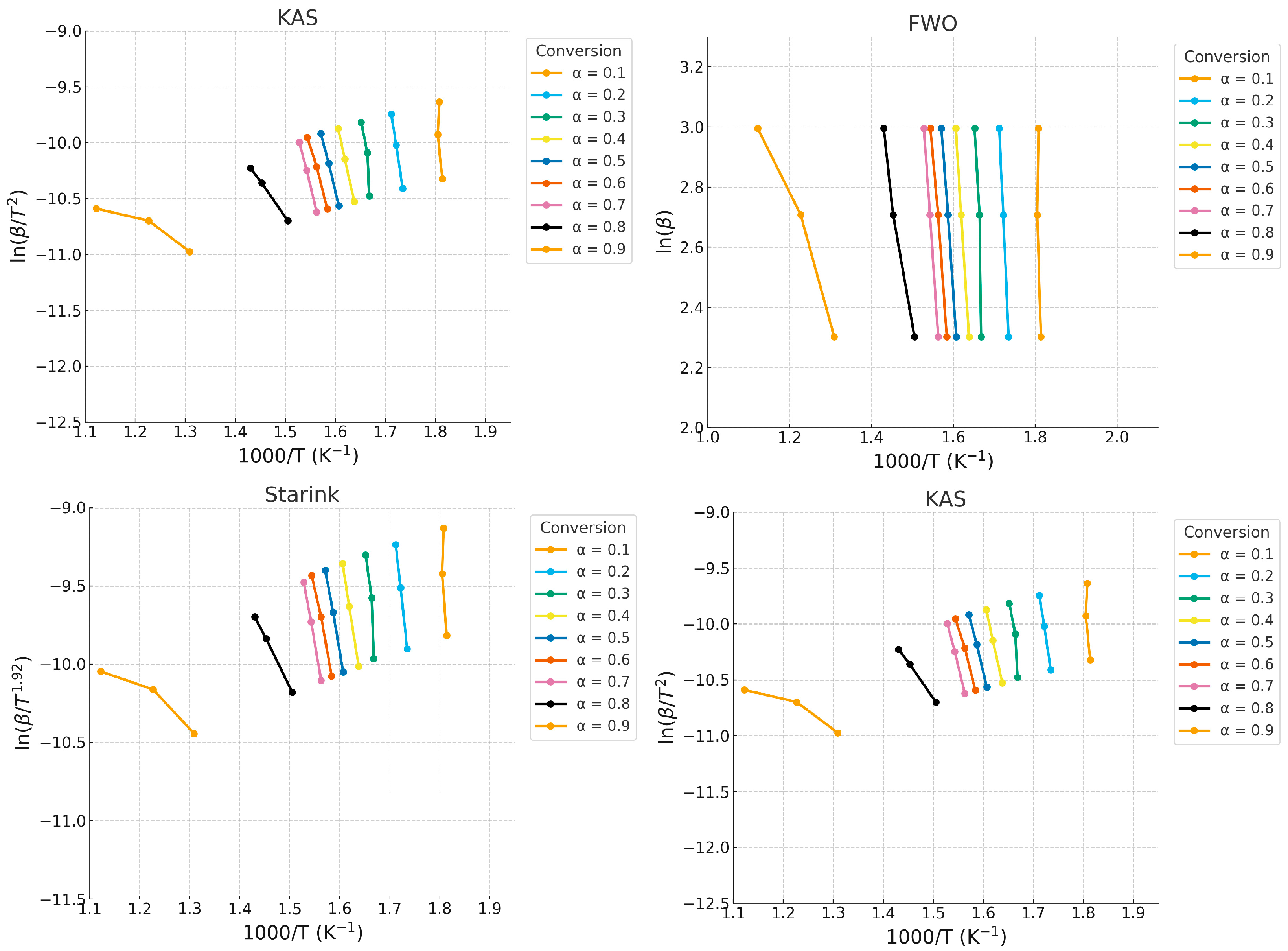

3.4.2. Iso-Conversional Method Using FWO, KAS, Starink, and Friedman

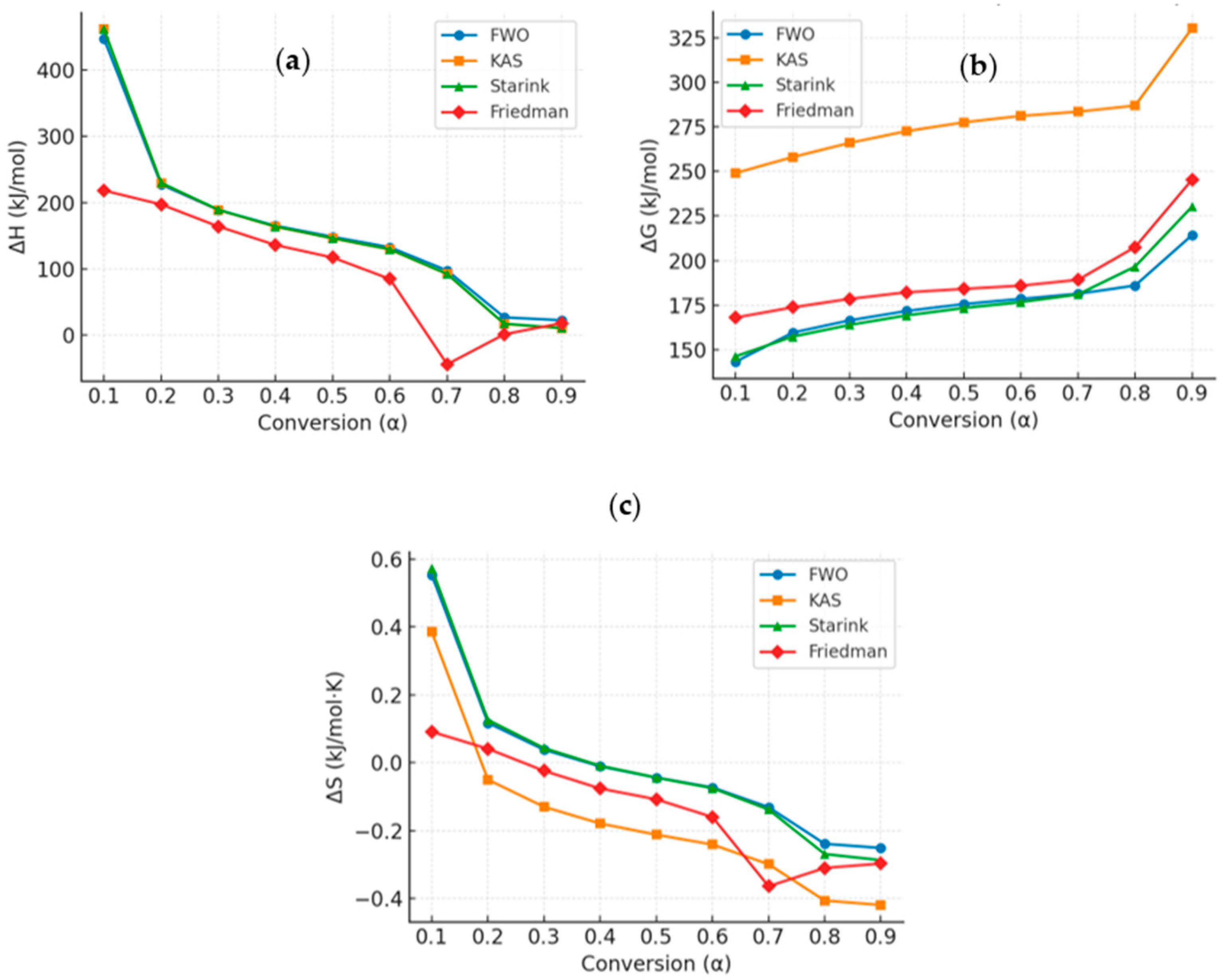

3.5. Thermodynamic Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Biomass Explained: Use of Biomass for Energy. 2024. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/biomass (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Ember Climate. Global Electricity Review 2024. Available online: https://ember-climate.org/insights/research/global-electricity-review-2024 (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Koons, E. Biomass Energy in the Philippines: From Waste to Power. Energy Tracker Asia. 24 October 2024. Available online: https://energytracker.asia/biomass-energy-in-the-philippines (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Department of Energy (DOE), Philippines. Philippine Energy Plan 2023–2040. Available online: https://legacy.doe.gov.ph/pep/philippine-energy-plan-2020-2040-1 (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Yao, M.G. Pili (Canarium ovatum Engl.) Nut Shell Activated Carbon: Surface Modification, Characterization and Application for Carbon Dioxide Capture. 2012. Available online: https://animorepository.dlsu.edu.ph/etd_masteral/4112/ (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Prado, J.; Mendez, J.C.; Brillante, F.; Ocampo, D. Utilization of Pili (Canarium ovatum) sawdust in bio-crude oil production and identification of potential by-products through thermochemical conversion. Acta Chim. Asiana 2024, 7, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacho, J.L.; Reyes, S.R.; Santos, M.R.; Jocson, J.C.; Bernardo, E.L. Testing and evaluation of biomass roasting furnace using Pili Shell. Divers. J. 2023, 8, 3194–3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noszczyk, T.; Dyjakon, A.; Koziel, J.A. Kinetic Parameters of Nut Shells Pyrolysis. Energies 2021, 14, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagnade, P.; Panwar, N.L. Kinetic and Thermogravimetric Analysis of Rice Husk and Its Derived Biochar. Lett. Appl. NanoBioSci. 2024, 13, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awogbemi, O.; Kallon, D.V.V. Valorization of agricultural wastes for biofuel applications. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.K.; Wooten, J.B.; Baliga, V.L.; Lin, X.; Chan, W.G.; Hajaligol, M.R. Characterization of chars from pyrolysis of lignin. Fuel 2004, 83, 1469–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lei, H.; Liu, J.; Bu, Q.; Ren, S.; Zhang, Q.; Tang, J.; Ruan, R. Thermal decomposition behavior and kinetics for pyrolysis and catalytic pyrolysis of Douglas fir. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 33364–33374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coats, A.W.; Redfern, J.P. Kinetic parameters from thermogravimetric data. Nature 1964, 201, 68–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, A.K.; Braun, R.L. Global kinetic analysis of complex materials. Energy Fuels 1999, 13, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, Q.-V.; Chen, W.-H. Pyrolysis characteristics and kinetics of microalgae via thermogravimetric analysis (TGA): A state-of-the-art review. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 246, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starink, M.J. A new method for the derivation of activation energies from experiments performed at constant heating rate. Thermochim. Acta 1996, 288, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissinger, H.E. Reaction kinetics in differential thermal analysis. Anal. Chem. 1957, 29, 1702–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, H.L. Kinetics of thermal degradation of char-forming plastics from thermogravimetry: Application to a phenolic plastic. J. Polym. Sci. Part C Polym. Symp. 1964, 6, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyazovkin, S.; Burnham, A.K.; Criado, J.M.; Pérez-Maqueda, L.A.; Popescu, C.; Sbirrazzuoli, N. ICTAC Kinetics Committee recommendations for performing kinetic computations on thermal analysis data. Thermochim. Acta 2011, 520, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, J.H.; Wall, L.A. A quick, direct method for the determination of activation energy from thermogravimetric data. J. Polym. Sci. Part B 1966, 4, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monir, M.U.; Shovon, S.M.; Akash, F.A.; Habib, A.; Techato, K.; Aziz, A.A.; Chowdhury, S.; Prasetya, T.A.E. Comprehensive Characterization and Kinetic Analysis of Coconut Shell Thermal Degradation: Energy Potential Evaluated via the Coats–Redfern Method. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 55, 104186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D4442-20; Standard Test Methods for Direct Moisture Content Measurement of Wood and Wood-Based Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM D1762-84; Standard Test Method for Chemical Analysis of Wood Charcoal. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1984.

- Speight, J.G. Handbook of Coal Analysis, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Interscience: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 144–169. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D3286-91(2015); Standard Test Method for Gross Calorific Value of Solid Fuel by the Isothermal Jacket Bomb Calorimeter. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- Özyuğuran, Ö. Prediction of Calorific Value of Biomass Based on Elemental Analysis. Int. Adv. Res. Eng. J. 2018, 2, 254–260. [Google Scholar]

- TAPPI. TAPPI T203 cm-99: Alpha-, Beta- and Gamma-Cellulose in Pulp; TAPPI Press: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Teramoto, Y.; Lee, S.H.; Endo, T. Cost reduction and feedstock diversity for sulfuric acid-free ethanol cooking of lignocellulosic biomass as a pretreatment to enzymatic saccharification. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 4783–4789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluiter, A.; Ruiz, R.; Scarlata, C.; Sluiter, J.; Templeton, D. Determination of Extractives in Biomass; NREL/TP-510-42619; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sluiter, A.; Hames, B.; Ruiz, R.; Scarlata, C.; Sluiter, J.; Templeton, D.; Crocker, D. Determination of Structural Carbohydrates and Lignin in Biomass: Laboratory Analytical Procedure (LAP); NREL/TP-510-42618; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Templeton, D.W.; Sluiter, A.D. Determination of Acid-Soluble Lignin in Biomass; NREL/TP-510-42617; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Savitzky, A.; Golay, M.J.E. Smoothing and Differentiation of Data by Simplified Least Squares Procedures. Anal. Chem. 1964, 36, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, N.H.; Anh, K.D.; Gia, L.; Ha, T.A.; Thu, T. Pyrolysis of cashew nut shell: A parametric study. Vietnam J. Chem. 2020, 58, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gupta, R.; Zhang, Q.; You, S. Review of biochar production via crop residue pyrolysis: Development and perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 369, 128423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerrayya, A.; Shree Vishnu, A.K.; Shreyas, S.; Chakravarthy, S.R.; Vinu, R. Hydrothermal Liquefaction of Rice Straw Using Methanol as Co-Solvent. Energies 2020, 13, 2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xu, R.; Yan, C.; Han, L.; Lei, H.; Ruan, R.; Zhang, X. Fast hydrothermal co-liquefaction of corn stover and cow manure for biocrude and hydrochar production. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 340, 125630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Tao, W. CFBC and BFBC of low-rank coals. In Low-Rank Coals for Power Generation, Fuel and Chemical Production; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, C.; Champagne, P. Overview of recent advances in thermochemical conversion of biomass. Energy Convers. Manag. 2010, 51, 969–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xiao, R.; Wang, D.; He, G.; Shao, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, Z.; Chen, R. Biomass fast pyrolysis in a fluidized bed reactor under N2, CO2, CO, CH4 and H2 atmospheres. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 4258–4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imran, A.; Bramer, E.A.; Seshan, K.; Brem, G. An Overview of Catalysts in Biomass Pyrolysis for Production of Biofuels. Biofuel Res. J. 2018, 5, 872–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Paiva, I.; de Morais, E.G.; Jindo, K.; Silva, C.A. Biochar N content, pools and aromaticity as affected by feedstock and pyrolysis temperature. Waste Biomass Valorization 2024, 15, 3599–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronsse, F.; van Hecke, S.; Dickinson, D.; Prins, W. Production and characterization of slow pyrolysis biochar: Influence of feedstock type and pyrolysis conditions. GCB Bioenergy 2013, 5, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogalakshmi, K.N.; Natarajan, E.; Dutta, A. Lignocellulosic Biomass-Based Pyrolysis: A Comprehensive Review. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, D.; Xiao, R.; Gu, S.; Luo, K. The Pyrolytic Behavior of Cellulose in Lignocellulosic Biomass: A Review. RSC Adv. 2011, 1, 1641–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yan, R.; Chen, H.; Lee, D.H.; Zheng, C. Characteristics of Hemicellulose, Cellulose and Lignin Pyrolysis. Fuel 2007, 86, 1781–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.-B.; Lu, Q.; Ye, X.-N.; Xiao, L.-P.; Dong, C.-Q.; Liu, Y.-Q. Selective Production of Phenolic-Rich Bio-Oil from Catalytic Fast Pyrolysis of Biomass: Comparison of K3PO4, K2HPO4, and KH2PO4. 2014. Available online: https://bioresources.cnr.ncsu.edu/resources/selective-production-of-phenolic-rich-bio-oil-from-catalytic-fast-pyrolysis-of-biomass-comparison-of-k3po4-k2hpo4-and-kh2po4/ (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Lu, Q.; Li, W.Z.; Zhu, X.F. Overview of Fuel Properties of Biomass Fast Pyrolysis Oils. Energy Convers. Manag. 2009, 50, 1376–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, T.Q.; Lima, S.B.; Pires, C.A. Influence of Extractives on the Composition of Bio-Oil from Biomass Pyrolysis—A Review. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2024, 186, 106919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saddawi, A.; Jones, J.M.; Williams, A. Influence of Alkali Metals on the Kinetics of the Thermal Decomposition of Biomass. Fuel Process. Technol. 2012, 104, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slopiecka, K.; Bartocci, P.; Fantozzi, F. Thermogravimetric analysis and kinetic study of poplar wood pyrolysis. Appl. Energy 2012, 97, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongomin, O.; Nzila, C.; Igadwa Mwasiagi, J.; Maube, O. Comprehensive thermal properties, kinetic, and thermodynamic analyses of biomass wastes pyrolysis via TGA and Coats–Redfern methodologies. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 24, 100723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, R.; Castells, B.; Tascón, A. Thermogravimetric assessment of biomass: Unravelling kinetic, chemical composition and combustion profiles. Fire 2024, 7, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, L.G.; Silva, J.; Teixeira, S.; Soares, D.; Ferreira, M.; Teixeira, J. Influence of operating conditions on the thermal behavior and kinetics of pine wood particles using thermogravimetric analysis. Energies 2020, 13, 2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.-J.; Mo, W.-L.; Ma, Y.-Y.; He, X.-Q.; Syls, Y.; Wei, X.-Y.; Fan, X.; Yang, X.-Q.; Zhang, S.-P. Pyrolysis kinetic analysis of sequential extract residues from Hefeng subbituminous coal based on the Coats–Redfern method. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 21397–21406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, I.; Li, X.; Jian, Y.; Dacres, O.D.; Zhong, M.; Liu, J.; Ma, F.; Rahman, N. Kinetic study of biomass pellet pyrolysis by using distributed activation energy model and Coats–Redfern methods and their comparison. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 294, 122099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.; Abu-Jdayil, B.; Inayat, A. Pyrolytic kinetics and thermodynamic analyses of date seeds at different heating rates using the Coats–Redfern method. Fuel 2023, 342, 127799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emiola-Sadiq, T.; Zhang, L.; Dalai, A.K. Thermal and kinetic studies on biomass degradation via thermogravimetric analysis: A combination of model-fitting and model-free approach. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 22233–22247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarado Flores, J.J.; Alcaraz Vera, J.V.; Ávalos Rodríguez, M.L.; López Sosa, L.B.; Rutiaga Quiñones, J.G.; Pintor Ibarra, L.F.; Márquez Montesino, F.; Aguado Zarraga, R. Analysis of pyrolysis kinetic parameters based on various mathematical models for more than twenty different biomasses: A review. Energies 2022, 15, 6524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Ye, X.; Wang, H.; Zhao, D. Insights into pyrolysis kinetics, thermodynamics, and the reaction mechanism of wheat straw for its resource utilization. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, C.N.; Navarro, M.V.; Martínez, J.D. Pyrolysis kinetics of biomass wastes using isoconversional methods and the distributed activation energy model. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 288, 121485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerzak, W.; Reinmöller, M.; Magdziarz, A. Estimation of the heat required for intermediate pyrolysis of biomass. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2022, 24, 3061–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, M.; Pan, X.; Zhu, X. Kinetic Parameters of Biomass Pyrolysis by TGA. 2016. Available online: https://bioresources.cnr.ncsu.edu/resources/kinetic-parameters-of-biomass-pyrolysis-by-tga/ (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Patil, Y.; Ku, X.; Vasudev, V. Pyrolysis characteristics and determination of kinetic and thermodynamic parameters of raw and torrefied Chinese fir. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 34938–34947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Mohanty, K. Insight into the pyrolysis of Melocanna baccifera biomass: Pyrolysis behavior, kinetics, and thermodynamic parameters analysis based on iso-conversional methods. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 8420–8432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model Name | Symbol | |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Order Models (CRO) | ||

| 0th Order | CRO0 | |

| 1st Order | CRO1 | |

| 1.5th Order | CRO1.5 | |

| 2nd Order | CRO2 | |

| 3rd Order | CRO3 | |

| Diffusion-Controlled Models (DM) | ||

| 1-way Transport | DM1 | |

| 2-way Transport | DM2 | |

| 3-way Transport | DM3 | |

| Valensi Equation | DM4 | |

| Ginstling-Brounstein Equation | DM5 | |

| Zhuravlev Equation | DM6 | |

| Jander Equation | DM7 | |

| Ginstling Equation | DM8 | |

| Geometrical Contraction Models (GM) | ||

| Cylindrical Shape | GM1 | |

| Sphere Shape | GM2 | |

| Power Law Models | ||

| 1/2 Power Law | NM1 | |

| 1/3 Power Law | NM2 | |

| 1/4 Power Law | NM3 | |

| Nucleation Models (Avrami–Erofeev Type) (NM) | ||

| 1/2 Avrami-Erofeev Equation | NM4 | |

| 1/3 Avrami-Erofeev Equation | NM5 | |

| 2/3 Avrami-Erofeev Equation | NM6 | |

| Composition | Value (wt%) |

|---|---|

| Hemicellulose | 25.95 ± 0.53 |

| Cellulose | 33.84 ± 0.53 |

| Lignin | 36.44 ± 2.21 |

| Extractives | 3.77 ± 0.08 |

| Β (°C/min) | Ti | Tp | ΔT1/2 | Tf | −Rp | −Rv | tf | WL | Mr | TG Total | D (%2 °C−3min−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (°C) | (%/min) | (min) | (wt%) | ||||||||

| 10 | 107.50 | 358.33 | 219.83 | 544.67 | 9.00 | 1.27 | 57.90 | 67.70 | 24.87 | 75.13 | 3.45 × 10−7 |

| 15 | 107.75 | 365.75 | 269.88 | 644.75 | 12.47 | 1.53 | 49.87 | 69.20 | 23.24 | 76.76 | 4.28 × 10−7 |

| 20 | 108.67 | 369.333 | 289.50 | 684.00 | 15.37 | 1.93 | 43.00 | 73.48 | 16.92 | 83.08 | 4.47 × 10−7 |

| Kinetics | 10 °C/min | 15 °C/min | 20 °C/min | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ea (kJ/mol) | A (min−1) | R2 | Ea (kJ/mol) | A (min−1) | R2 | Ea (kJ/mol) | A (min−1) | R2 | |

| Reaction Order Models | |||||||||

| CR00 | 26.15 | 5.16 × 10−2 | 0.65 | 20.20 | 7.57 × 10−3 | 0.55 | 13.53 | 9.68 × 10−4 | 0.42 |

| CR01 | 42.51 | 2.91 × 100 | 0.82 | 34.40 | 2.84 × 10−1 | 0.76 | 25.25 | 2.34 × 10−2 | 0.69 |

| CR01.5 | 80.64 | 5.59 × 104 | 0.94 | 67.85 | 2.03 × 103 | 0.92 | 52.78 | 5.20 × 101 | 0.91 |

| CR02 | 66.30 | 7.28 × 102 | 0.92 | 55.27 | 3.85 × 101 | 0.89 | 42.41 | 1.54 × 100 | 0.86 |

| CR03 | 96.21 | 6.02 × 105 | 0.95 | 81.50 | 1.45 × 104 | 0.94 | 64.03 | 2.28 × 102 | 0.94 |

| Diffusion-Controlled Models | |||||||||

| DM1 | 63.04 | 6.35 × 101 | 0.74 | 51.51 | 3.02 × 100 | 0.67 | 38.65 | 1.21 × 10−1 | 0.61 |

| DM2 | 9.45 | 3.18 × 10−3 | 0.76 | 6.39 | 7.47 × 10−4 | 0.62 | 2.76 | 1.14 × 10−4 | 0.31 |

| DM3 | 24.76 | 6.50 × 10−2 | 0.77 | 19.30 | 1.05 × 10−2 | 0.68 | 12.97 | 1.45 × 10−3 | 0.56 |

| DM4 | 71.76 | 2.45 × 102 | 0.78 | 59.08 | 9.15 × 100 | 0.72 | 44.87 | 2.79 × 10−1 | 0.66 |

| DM5 | 75.52 | 1.29 × 102 | 0.79 | 62.35 | 4.36 × 100 | 0.74 | 47.56 | 1.18 × 10−1 | 0.69 |

| DM6 | 109.99 | 3.12 × 105 | 0.89 | 92.46 | 4.17 × 103 | 0.86 | 72.34 | 3.82 × 101 | 0.83 |

| DM7 | 83.22 | 7.52 × 102 | 0.82 | 69.07 | 2.06 × 101 | 0.77 | 53.09 | 4.39 × 10−1 | 0.73 |

| DM8 | 75.48 | 1.27 × 102 | 0.79 | 62.32 | 4.30 × 100 | 0.74 | 47.53 | 1.17 × 10−1 | 0.69 |

| Geometrical Contraction Models | |||||||||

| GM1 | 33.43 | 1.61 × 10−1 | 0.74 | 26.52 | 1.98 × 10−2 | 0.66 | 18.73 | 2.11 × 10−3 | 0.56 |

| GM2 | 36.24 | 2.14 × 10−1 | 0.77 | 28.98 | 2.45 × 10−2 | 0.70 | 20.75 | 2.42 × 10−3 | 0.61 |

| Power Law Models | |||||||||

| NM1 | 7.71 | 6.73 × 10−4 | 0.38 | 4.54 | 1.36 × 10−4 | 0.19 | 0.98 | 1.06 × 10−5 | 0.01 |

| NM2 | 1.56 | 4.81 × 10−5 | 0.05 | −0.68 | −8.75 × 10−6 | 0.01 | −3.21 | −1.85 × 10−5 | 0.23 |

| NM3 | −1.52 | −2.79 × 10−5 | 0.08 | −3.29 | −2.79 × 10−5 | 0.29 | −5.30 | −2.24 × 10−5 | 0.57 |

| Nucleation Models (Avrami–Erofeev Type) | |||||||||

| NM4 | 15.88 | 8.17 × 10−3 | 0.71 | 11.67 | 1.64 × 10−3 | 0.58 | 6.83 | 2.66 × 10−4 | 0.37 |

| NM5 | 7.01 | 7.06 × 10−4 | 0.5 | 4.07 | 1.47 × 10−4 | 0.26 | 0.69 | 9.42 × 10−6 | 0.01 |

| NM6 | 24.76 | 6.50 × 10−2 | 0.77 | 19.26 | 1.05 × 10−2 | 0.68 | 12.97 | 1.45 × 10−3 | 0.56 |

| Model | T (K) | α | Ea (kJ/mol) | A (min−1) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FWO | 552.91 | 0.1 | 451.85 | 4.44× 1043 | 0.54480 |

| 580.41 | 0.2 | 231.91 | 9.69 × 1020 | 0.99997 | |

| 600.45 | 0.3 * | 193.75 * | 6.92 × 1016 | 0.99996 | |

| 616.98 | 0.4 * | 170.08 * | 2.06 × 1014 | 0.99998 | |

| 629.62 | 0.5 * | 153.52 * | 4.06 × 1012 | 0.99913 | |

| 639.57 | 0.6 * | 137.82 * | 1.25 × 1011 | 0.99611 | |

| 650.98 | 0.7 | 102.89 | 1.17 × 108 | 0.97704 | |

| 699.12 | 0.8 | 32.45 | 2.75 × 102 | 0.90708 | |

| 823.43 | 0.9 | 28.95 | 7.45 × 101 | 0.97212 | |

| Average * | 163.29 * | ||||

| KAS | 552.91 | 0.1 | 466.15 | 9.23 × 1034 | 0.53509 |

| 580.41 | 0.2 | 234.33 | 1.87 × 1012 | 0.99997 | |

| 600.45 | 0.3 * | 193.85 * | 1.26 × 108 | 0.99996 | |

| 616.98 | 0.4 * | 168.67 * | 3.57 × 105 | 0.99997 | |

| 629.62 | 0.5 * | 151.04 * | 6.82 × 103 | 0.99899 | |

| 639.57 | 0.6 * | 134.36 * | 2.06 × 102 | 0.99544 | |

| 650.98 | 0.7 | 97.40 | 1.91 × 10−1 | 0.97163 | |

| 699.12 | 0.8 | 22.42 | 5.23 × 10−7 | 0.80368 | |

| 823.43 | 0.9 | 16.73 | 1.23 × 10−7 | 0.90388 | |

| Average * | 163.74 * | ||||

| Starink | 552.91 | 0.1 | 466.15 | 5.21 × 1044 | 0.53548 |

| 580.41 | 0.2 | 234.52 | 2.68 × 1021 | 0.99997 | |

| 600.45 | 0.3 * | 194.10 * | 1.24 × 1017 | 0.99996 | |

| 616.98 | 0.4 * | 168.95 * | 2.67 × 1014 | 0.99997 | |

| 629.62 | 0.5 * | 151.34 * | 4.09 × 1012 | 0.99899 | |

| 639.57 | 0.6 * | 134.68 * | 9.79 × 1010 | 0.99547 | |

| 650.98 | 0.7 | 97.76 | 4.78 × 107 | 0.97188 | |

| 699.12 | 0.8 | 22.87 | 7.10 × 100 | 0.81030 | |

| 823.43 | 0.9 | 17.26 | 9.56 × 10−1 | 0.90970 | |

| Average * | 163.90 * | ||||

| Friedman | 552.91 | 0.1 | 222.73 | 3.91 × 1019 | 0.76351 |

| 580.41 | 0.2 | 201.96 | 9.66 × 1016 | 0.99981 | |

| 600.45 | 0.3 * | 168.98 * | 4.01 × 1013 | 0.99756 | |

| 616.98 | 0.4 * | 141.05 * | 8.55 × 1010 | 0.99984 | |

| 629.62 | 0.5 * | 122.28 * | 1.86 × 109 | 0.99134 | |

| 639.57 | 0.6 * | 90.05 * | 3.42 × 106 | 0.95767 | |

| 650.98 | 0.7 | 38.50 | 7.80 × 10−5 | 0.34351 | |

| 699.12 | 0.8 | 7.01 | 5.59 × 10−2 | 0.25998 | |

| 823.43 | 0.9 | 24.58 | 2.77 × 10−1 | 0.88973 | |

| Average * | 132.03 * |

| Kinetics | 10 °C/min | 15 °C/min | 20 °C/min | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔH | ΔG | ΔS | ΔH | ΔG | ΔS | ΔH | ΔG | ΔS | |

| Reaction Order Models | |||||||||

| CR00 | 20.89 | 217.13 | −309.86 | 14.88 | 223.38 | −325.90 | 8.17 | 229.39 | −343.07 |

| CR01 | 37.25 | 212.25 | −276.34 | 29.08 | 218.30 | −295.77 | 19.89 | 224.04 | −316.59 |

| CR01.5 | 75.38 | 198.45 | −194.33 | 62.53 | 204.54 | −221.98 | 47.42 | 210.25 | −252.52 |

| CR02 | 61.04 | 206.97 | −230.42 | 49.95 | 213.05 | −254.95 | 37.05 | 218.75 | −281.78 |

| CR03 | 90.95 | 201.51 | −174.57 | 76.18 | 207.74 | −205.64 | 58.67 | 213.58 | −240.23 |

| Diffusion-Controlled Models | |||||||||

| DM1 | 57.78 | 216.55 | −250.70 | 46.19 | 222.83 | −276.11 | 33.29 | 228.63 | −302.93 |

| DM2 | 4.18 | 215.10 | −333.03 | 1.07 | 221.89 | −345.16 | −2.60 | 230.09 | −360.85 |

| DM3 | 19.50 | 214.52 | −307.94 | 13.98 | 220.74 | −323.18 | 7.61 | 226.67 | −339.71 |

| DM4 | 66.50 | 218.16 | −239.48 | 53.76 | 224.51 | −266.90 | 39.51 | 230.37 | −295.98 |

| DM5 | 70.26 | 225.30 | −244.81 | 57.03 | 231.72 | −273.06 | 42.20 | 237.67 | −303.13 |

| DM6 | 104.72 | 218.75 | −180.04 | 87.14 | 225.33 | −216.00 | 66.98 | 231.46 | −255.08 |

| DM7 | 77.96 | 223.72 | −230.16 | 63.75 | 230.18 | −260.15 | 47.73 | 236.16 | −292.21 |

| DM8 | 70.22 | 225.34 | −244.94 | 57.00 | 231.76 | −273.17 | 42.17 | 237.69 | −303.20 |

| Geometrical Contraction Models | |||||||||

| GM1 | 28.17 | 218.41 | −300.40 | 21.20 | 224.58 | −317.91 | 13.37 | 230.42 | −336.59 |

| GM2 | 30.98 | 219.73 | −298.03 | 23.66 | 225.91 | −316.14 | 15.39 | 231.70 | −335.45 |

| Power Law Models | |||||||||

| NM1 | 2.44 | 221.54 | −345.94 | −0.78 | 229.10 | −359.32 | −4.38 | 241.05 | −380.60 |

| NM2 | −3.71 | 229.28 | −367.88 | −6.00 | – | – | −8.57 | – | – |

| NM3 | −6.79 | – | – | −8.61 | – | – | −10.66 | – | – |

| Nucleation Models (Avrami–Erofeev Type) | |||||||||

| NM4 | 10.62 | 216.56 | −325.18 | 6.35 | 222.98 | −338.62 | 1.47 | 229.62 | −353.81 |

| NM5 | 1.74 | 220.58 | −345.54 | −1.25 | 228.21 | −358.67 | −4.67 | 241.39 | −381.58 |

| NM6 | 19.50 | 214.52 | −307.94 | 13.94 | 220.70 | −323.18 | 7.61 | 226.67 | −339.71 |

| Kinetics | 10 °C/min | 15 °C/min | 20 °C/min | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔH | ΔG | ΔS | ΔH | ΔG | ΔS | ΔH | ΔG | ΔS | |

| FWO | |||||||||

| 0.1 | 447.262 | 143.158 | 0.552 | 447.240 | 141.676 | 0.551 | 447.247 | 142.147 | 0.551 |

| 0.2 | 227.121 | 159.515 | 0.117 | 227.082 | 158.969 | 0.117 | 227.055 | 158.583 | 0.117 |

| 0.3 | 188.807 | 166.384 | 0.038 | 188.757 | 166.160 | 0.038 | 188.722 | 166.002 | 0.038 |

| 0.4 | 165.005 | 171.664 | −0.011 | 164.946 | 171.741 | −0.011 | 164.903 | 171.799 | −0.011 |

| 0.5 | 148.345 | 175.543 | −0.044 | 148.280 | 175.886 | −0.044 | 148.228 | 176.163 | −0.044 |

| 0.6 | 132.574 | 178.491 | −0.073 | 132.503 | 179.112 | −0.073 | 132.439 | 179.677 | −0.073 |

| 0.7 | 97.564 | 181.330 | −0.131 | 97.481 | 182.633 | −0.131 | 97.377 | 184.264 | −0.131 |

| 0.8 | 26.921 | 185.933 | −0.239 | 26.733 | 191.356 | −0.239 | 26.271 | 204.643 | −0.240 |

| 0.9 | 22.598 | 214.296 | −0.251 | 22.172 | 227.146 | −0.251 | 21.539 | 246.330 | −0.252 |

| Average | 161.800 | 175.146 | −0.005 | 161.688 | 177.187 | −0.005 | 161.531 | 181.068 | −0.005 |

| KAS | |||||||||

| 0.1 | 461.568 | 249.114 | 0.385 | 461.546 | 248.079 | 0.385 | 461.553 | 248.408 | 0.385 |

| 0.2 | 229.535 | 258.066 | −0.050 | 229.497 | 258.297 | −0.050 | 229.469 | 258.460 | −0.050 |

| 0.3 | 188.905 | 266.051 | −0.130 | 188.856 | 266.825 | −0.130 | 188.821 | 267.371 | −0.130 |

| 0.4 | 163.598 | 272.646 | −0.179 | 163.539 | 273.907 | −0.179 | 163.496 | 274.835 | −0.179 |

| 0.5 | 145.866 | 277.592 | −0.212 | 145.801 | 279.252 | −0.212 | 145.749 | 280.591 | −0.212 |

| 0.6 | 129.111 | 281.188 | −0.241 | 129.040 | 283.245 | −0.241 | 128.976 | 285.112 | −0.241 |

| 0.7 | 92.081 | 283.550 | −0.299 | 91.999 | 286.528 | −0.299 | 91.895 | 290.252 | −0.299 |

| 0.8 | 16.884 | 287.000 | −0.406 | 16.696 | 296.209 | −0.406 | 16.235 | 318.757 | −0.407 |

| 0.9 | 10.375 | 330.489 | −0.419 | 9.950 | 351.938 | −0.420 | 9.317 | 383.927 | −0.420 |

| Average | 159.769 | 278.411 | −0.172 | 159.658 | 282.698 | −0.172 | 159.501 | 289.746 | −0.172 |

| Starink | |||||||||

| 0.1 | 461.563 | 146.172 | 0.572 | 461.540 | 149.242 | 0.564 | 461.547 | 149.723 | 0.564 |

| 0.2 | 229.733 | 157.263 | 0.126 | 229.695 | 161.507 | 0.117 | 229.667 | 161.121 | 0.117 |

| 0.3 | 189.149 | 163.850 | 0.043 | 189.100 | 168.594 | 0.034 | 189.065 | 168.450 | 0.034 |

| 0.4 | 163.873 | 169.211 | −0.009 | 163.814 | 174.408 | −0.017 | 163.771 | 174.497 | −0.017 |

| 0.5 | 146.164 | 173.317 | −0.044 | 146.099 | 178.899 | −0.052 | 146.046 | 179.228 | −0.052 |

| 0.6 | 129.428 | 176.639 | −0.075 | 129.357 | 182.597 | −0.083 | 129.293 | 183.242 | −0.083 |

| 0.7 | 92.436 | 180.969 | −0.138 | 92.354 | 187.752 | −0.147 | 92.250 | 189.579 | −0.147 |

| 0.8 | 17.335 | 196.575 | −0.269 | 17.146 | 208.409 | −0.278 | 16.685 | 223.844 | −0.279 |

| 0.9 | 10.911 | 230.276 | −0.287 | 10.485 | 251.755 | −0.296 | 9.852 | 274.331 | −0.297 |

| Average | 160.066 | 177.141 | −0.009 | 159.954 | 184.796 | −0.018 | 159.797 | 189.335 | −0.018 |

| Friedman | |||||||||

| 0.1 | 218.146 | 167.970 | 0.091 | 218.124 | 172.332 | 0.083 | 218.131 | 172.403 | 0.083 |

| 0.2 | 197.169 | 173.703 | 0.041 | 197.130 | 178.343 | 0.032 | 197.103 | 178.236 | 0.032 |

| 0.3 | 164.031 | 178.481 | −0.024 | 163.981 | 183.623 | −0.033 | 163.946 | 183.761 | −0.033 |

| 0.4 | 135.974 | 182.154 | −0.076 | 135.915 | 187.823 | −0.084 | 135.872 | 188.260 | −0.084 |

| 0.5 | 117.108 | 184.073 | −0.108 | 117.043 | 190.156 | −0.116 | 116.991 | 190.890 | −0.116 |

| 0.6 | 84.802 | 185.883 | −0.160 | 84.731 | 192.571 | −0.169 | 84.667 | 193.876 | −0.169 |

| 0.7 | −43.826 | 189.172 | −0.364 | −43.909 | 198.201 | −0.372 | −44.013 | 202.836 | −0.373 |

| 0.8 | 1.475 | 207.518 | −0.310 | 1.286 | 220.265 | −0.318 | 0.825 | 237.934 | −0.319 |

| 0.9 | 18.232 | 245.466 | −0.297 | 17.807 | 267.473 | −0.306 | 17.173 | 290.834 | −0.307 |

| Average | 99.234 | 190.491 | −0.134 | 99.123 | 198.976 | −0.143 | 98.966 | 204.337 | −0.143 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Papa, K.; Lavarias, J.; Denson, M.; Paragas, D.; Tanquilut, M.R.; Morico, A. Characterization, Kinetic Studies, and Thermodynamic Analysis of Pili (Canarium ovatum Engl.) Nutshell for Assessing Its Biofuel Potential and Bioenergy Applications. Fuels 2026, 7, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/fuels7010002

Papa K, Lavarias J, Denson M, Paragas D, Tanquilut MR, Morico A. Characterization, Kinetic Studies, and Thermodynamic Analysis of Pili (Canarium ovatum Engl.) Nutshell for Assessing Its Biofuel Potential and Bioenergy Applications. Fuels. 2026; 7(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/fuels7010002

Chicago/Turabian StylePapa, Kaye, Jeffrey Lavarias, Melba Denson, Danila Paragas, Mari Rowena Tanquilut, and Arly Morico. 2026. "Characterization, Kinetic Studies, and Thermodynamic Analysis of Pili (Canarium ovatum Engl.) Nutshell for Assessing Its Biofuel Potential and Bioenergy Applications" Fuels 7, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/fuels7010002

APA StylePapa, K., Lavarias, J., Denson, M., Paragas, D., Tanquilut, M. R., & Morico, A. (2026). Characterization, Kinetic Studies, and Thermodynamic Analysis of Pili (Canarium ovatum Engl.) Nutshell for Assessing Its Biofuel Potential and Bioenergy Applications. Fuels, 7(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/fuels7010002