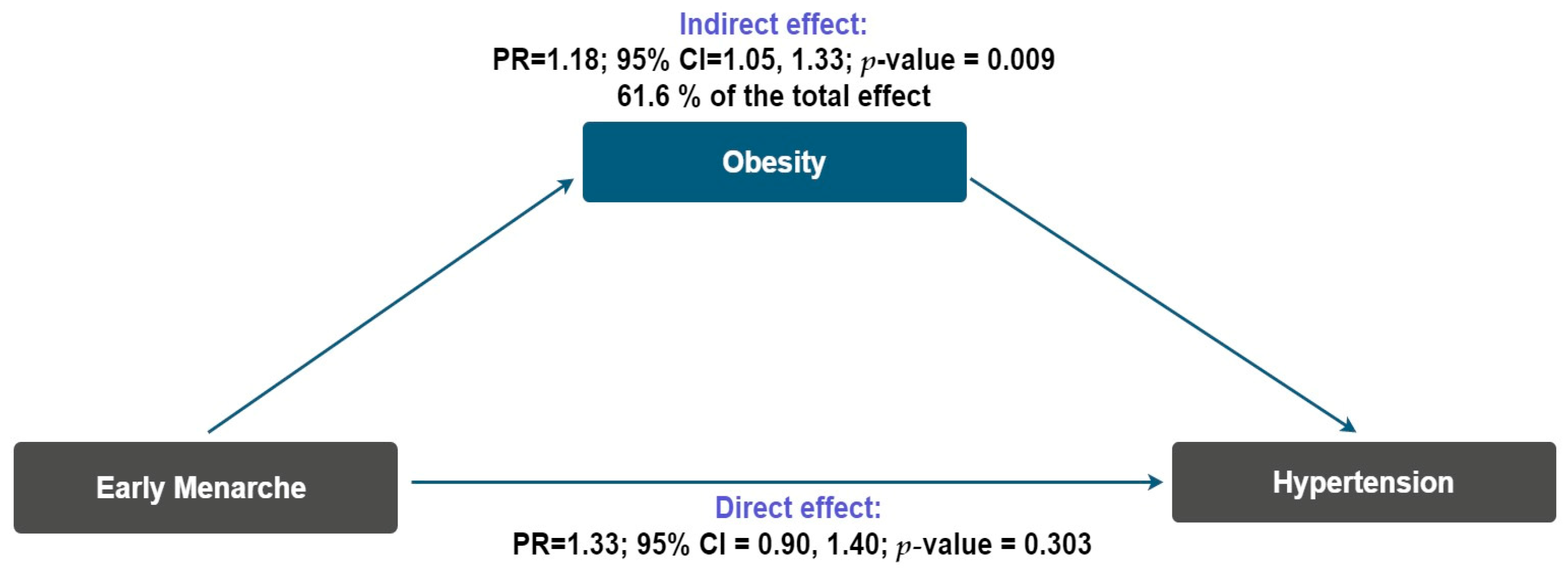

Early Menarche and Hypertension Among Postmenopausal Women: The Mediating Role of Obesity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Study Population

2.2. Study Variables

2.3. Data Collection Procedures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PR | Prevalence Ratio |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| DAG | Directed Acyclic Graph |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

References

- Resultados del GBD. Instituto de Métricas y Evaluación de la Salud. Available online: https://www.healthdata.org/data-tools-practices/interactive-visuals/gbd-results (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Kjeldsen, S.E. Hypertension and Cardiovascular Risk: General Aspects. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 129, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh, A.; Hammad, M.; Piña, I.L.; Kulinski, J. Obesity and Cardiovascular Health. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2024, 31, 1026–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos-Nonato, I.; Oviedo-Solís, C.; Vargas-Meza, J.; Ramírez-Villalobos, D.; Medina-García, C.; Gómez-Álvarez, E.; Hernández-Barrera, L.; Barquera, S. Prevalencia, tratamiento y control de la hipertensión arterial en adultos mexicanos: Resultados de la Ensanut 2022. Salud Pública México 2023, 65, s169–s180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, F.D.; Whelton, P.K. High Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Disease. Hypertension 2020, 75, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariq, O.A.; McKenzie, T.J. Obesity-Related Hypertension: A Review of Pathophysiology, Management, and the Role of Metabolic Surgery. Gland Surg. 2020, 9, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.N.M.S.; Sultana, H.; Refat, M.N.H.; Farhana, Z.; Abdulbasah Kamil, A.; Meshbahur Rahman, M. The Global Burden of Overweight-Obesity and Its Association with Economic Status, Benefiting from STEPs Survey of WHO Member States: A Meta-Analysis. Prev. Med. Rep. 2024, 46, 102882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, P.; Petersohn, I.; Salpea, P.; Malanda, B.; Karuranga, S.; Unwin, N.; Colagiuri, S.; Guariguata, L.; Motala, A.A.; Ogurtsova, K.; et al. Global and Regional Diabetes Prevalence Estimates for 2019 and Projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th Edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 157, 107843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opoku, A.A.; Abushama, M.; Konje, J.C. Obesity and Menopause. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2023, 88, 102348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romieu, I.; Dossus, L.; Barquera, S.; Blottière, H.M.; Franks, P.W.; Gunter, M.; Hwalla, N.; Hursting, S.D.; Leitzmann, M.; Margetts, B.; et al. Energy Balance and Obesity: What Are the Main Drivers? Cancer Causes Control 2017, 28, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, A.R.; Chavarro, J.E.; Oken, E. Reproductive Risk Factors Across the Female Lifecourse and Later Metabolic Health. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 240–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S. Why Should We Be Concerned About Early Menarche? Clin. Exp. Pediatr. 2020, 64, 26–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sanctis, V.; Rigon, F.; Bernasconi, S.; Bianchin, L.; Bona, G.; Bozzola, M.; Buzi, F.; De Sanctis, C.; Tonini, G.; Radetti, G.; et al. Age at Menarche and Menstrual Abnormalities in Adolescence: Does It Matter? The Evidence from a Large Survey among Italian Secondary Schoolgirls. Indian J. Pediatr. 2019, 86, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakshman, R.; Forouhi, N.G.; Sharp, S.J.; Luben, R.; Bingham, S.A.; Khaw, K.-T.; Wareham, N.J.; Ong, K.K. Early Age at Menarche Associated with Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 4953–4960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinho, L.C.A.P.; Zaniqueli, D.; Andreazzi, A.E.; de Oliveira, C.M.; Pereira, A.C.; Alvim, R. de O. Association Between Early Menarche and Hypertension in Pre and Postmenopausal Women: Baependi Heart Study. J. Hypertens. 2025, 43, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubach, S.; Horta, B.L.; Gonçalves, H.; Assunção, M.C.F. Early Age at Menarche and Metabolic Cardiovascular Risk Factors: Mediation by Body Composition in Adulthood. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Mao, D.; Chen, L.; Tang, W.; Ding, X. Associations Between Age at Menarche and Dietary Patterns with Blood Pressure in Southwestern Chinese Adults. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farahmand, M.; Mousavi, M.; Momenan, A.A.; Azizi, F.; Ramezani Tehrani, F. The Association Between Arterial Hypertension and Menarcheal Age. Maturitas 2023, 174, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, T.; Zhu, L.; Wen, M.; Hu, L.; Huang, X.; You, C.; Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Wu, Q.; et al. Association Between Age at Menarche and Hypertension among Females in Southern China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Hypertens. 2019, 2019, 9473182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; Zheng, C.; Kang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Z.; Gao, R. Age at Menarche and Risk of Hypertension in Chinese Adult Women: Results from a Large Representative Nationwide Population. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2021, 23, 1615–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, A.; Ahmadnia, Z.; Borghei, Y.; Rafiee, E.; Gholipour, M.; Mirrazeghi, S.F.; Karami, S. Associations of the Age of Menarche and Menopause with Hypertension in Menopausal Women in North of Iran: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Pract. 2025, 10, e166122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, J.C.; Hong, J.W.; Noh, J.H.; Kim, D.-J. Association Between Age at Menarche and Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Diseases in Korean Women. Medicine 2016, 95, e3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Song, C.; Jiang, J.; Chen, Y.; Liang, S.; Ma, N.; Dong, K.; Nie, W.; Wang, K. Association of Reproductive History with Hypertension and Prehypertension in Chinese Postmenopausal Women: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Hypertens. Res. 2018, 41, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werneck, A.O.; Oyeyemi, A.L.; Cyrino, E.S.; Ronque, E.R.V.; Szwarcwald, C.L.; Coelho-E-Silva, M.J.; Silva, D.R. Association Between Age at Menarche and Blood Pressure in Adulthood: Is Obesity an Important Mediator? Hypertens. Res. Off. J. Jpn. Soc. Hypertens. 2018, 41, 856–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yan, M.; Suolang, D.; Han, M.; Baima, Y.; Mi, F.; Chen, L.; Guan, H.; Cai, H.; Zhao, X.; et al. Mediation Effect of Obesity on the Association of Age at Menarche With Blood Pressure Among Women in Southwest China. J. Am. Heart Assoc. Cardiovasc. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2023, 12, e027544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Zhou, W.; Wang, C.; Dong, X.; Mao, Z.; Huo, W.; Tian, Z.; Fan, M.; Yang, X.; et al. Mediation Effect of BMI on the Relationship Between Age at Menarche and Hypertension: The Henan Rural Cohort Study. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2020, 34, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefzai, S.; Amin, Z.; Faizan, H.; Ali, M.; Soni, S.; Friedman, M.; Kazmi, A.; Metlock, F.E.; Sharma, G.; Javed, Z. Cardiovascular Health During Menopause Transition: The Role of Traditional and Nontraditional Risk Factors. Methodist DeBakey Cardiovasc. J. 2025, 21, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Nonato, I.; Hernández-Barrera, L.; Oviedo-Solís, C.; Ramírez-Villalobos, D.; Hernández, B.; Barquera, S.; Campos-Nonato, I.; Hernández-Barrera, L.; Oviedo-Solís, C.; Ramírez-Villalobos, D.; et al. Epidemiología de la hipertensión arterial en adultos Mexicanos: Diagnóstico, control y tendencias. Ensanut 2020. Salud Pública México 2021, 63, 692–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Consultation. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. World Health Organ. Tech. Rep. Ser. 2000, 894, 1–253. [Google Scholar]

- Canoy, D.; Beral, V.; Balkwill, A.; Wright, F.L.; Kroll, M.E.; Reeves, G.K.; Green, J.; Cairns, B.J.; Million Women Study Collaborators. Age at Menarche and Risks of Coronary Heart and Other Vascular Diseases in a Large UK Cohort. Circulation 2015, 131, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zárate, C.M.R.; Caballero, C.A.Z.; Hernández, F.V.M.; Robles, C.M.F.; Sánchez, A.M.R.; Ambe, A.K. Secular changes in onset of menarche among Mexican women. Ginecol. Obstet. México 2024, 92, 359–363. [Google Scholar]

- Marván, M.L.; Catillo-López, R.L.; Alcalá-Herrera, V.; Callejo, D.D. The Decreasing Age at Menarche in Mexico. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2016, 29, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnardellis, C.; Notara, V.; Papadakaki, M.; Gialamas, V.; Chliaoutakis, J. Overestimation of Relative Risk and Prevalence Ratio: Misuse of Logistic Modeling. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corraini, P.; Olsen, M.; Pedersen, L.; Dekkers, O.M.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. Effect Modification, Interaction and Mediation: An Overview of Theoretical Insights for Clinical Investigators. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017, 9, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, R.; Tingley, D. Causal Mediation Analysis. Stata J. 2011, 11, 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byeon, S.; Lee, W. An Introduction to Causal Mediation Analysis With a Comparison of 2 R Packages. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2023, 56, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digitale, J.C.; Martin, J.N.; Glymour, M.M. Tutorial on Directed Acyclic Graphs. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2022, 142, 264–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tennant, P.W.G.; Murray, E.J.; Arnold, K.F.; Berrie, L.; Fox, M.P.; Gadd, S.C.; Harrison, W.J.; Keeble, C.; Ranker, L.R.; Textor, J.; et al. Use of Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) to Identify Confounders in Applied Health Research: Review and Recommendations. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 50, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, P.; VanderWeele, T.J. Sensitivity Analysis Without Assumptions. Epidemiology 2016, 27, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, N.T.; Duncan, B.B.; Barreto, S.M.; Chor, D.; Bessel, M.; Aquino, E.M.; Pereira, M.A.; Schmidt, M.I. Earlier Age at Menarche is Associated with Higher Diabetes Risk and Cardiometabolic Disease Risk Factors in Brazilian Adults: Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil). Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2014, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Rhodes, L.; Malinowski, J.R.; Wang, Y.; Tao, R.; Pankratz, N.; Jeff, J.M.; Yoneyama, S.; Carty, C.L.; Setiawan, V.W.; Marchand, L.L.; et al. The Genetic Underpinnings of Variation in Ages at Menarche and Natural Menopause Among Women from the Multi-Ethnic Population Architecture using Genomics and Epidemiology (PAGE) Study: A Trans-Ethnic Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.W.; Ahn, J.H.; Lee, J.A.; Kim, D.H.; Seo, J.-H.; Lim, J.S. Early Menarche Is Associated with Metabolic Syndrome and Insulin Resistance in Premenopausal Korean Women. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2016, 175, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Nonato, I.; Galván-Valencia, Ó.; Hernández-Barrera, L.; Oviedo-Solís, C.; Barquera, S. Prevalencia de obesidad y factores de riesgo asociados en adultos Mexicanos: Resultados de la Ensanut 2022. Salud Pública México 2023, 65, s238–s247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersohn, I.; Zarate-Ortiz, A.G.; Cepeda-Lopez, A.C.; Melse-Boonstra, A. Time Trends in Age at Menarche and Related Non-Communicable Disease Risk during the 20th Century in Mexico. Nutrients 2019, 11, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, H.-W.; Kwon, A.-R.; Kim, D.-H.; Kim, H.-S. Sex Hormone Binding Globulin, Free Estradiol Index, and Lipid Profiles in Girls with Precocious Puberty. Ann. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 18, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbatini, A.R.; Kararigas, G. Estrogen-Related Mechanisms in Sex Differences of Hypertension and Target Organ Damage. Biol. Sex Differ. 2020, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heys, M.; Schooling, C.M.; Jiang, C.; Cowling, B.J.; Lao, X.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, K.K.; Adab, P.; Thomas, G.N.; Lam, T.H.; et al. Age of Menarche and the Metabolic Syndrome in China. Epidemiol. Camb. Mass 2007, 18, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Peng, C.; Xu, H.; Wilson, A.; Li, P.-H.; Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Shen, L.; Chen, X.; Qi, X.; et al. Age at Menarche and Prevention of Hypertension Through Lifestyle in Young Chinese Adult Women: Result from Project ELEFANT. BMC Womens Health 2018, 18, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakic, R.; Pavlica, T.; Havrljenko, J.; Bjelanovic, J. Association of Age at Menarche with General and Abdominal Obesity in Young Women. Medicina 2024, 60, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedman, D.S.; Khan, L.K.; Serdula, M.K.; Dietz, W.H.; Srinivasan, S.R.; Berenson, G.S. The Relation of Menarcheal Age to Obesity in Childhood and Adulthood: The Bogalusa Heart Study. BMC Pediatr. 2003, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubach, S.; Menezes, A.M.B.; Barros, F.C.; Wehrmeister, F.C.; Gonçalves, H.; Assunção, M.C.F.; Horta, B.L. Impact of the Age at Menarche on Body Composition in Adulthood: Results from two Birth Cohort Studies. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, C.; Yeung, E.; Ye, A.; Mumford, S.L.; Wactawski-Wende, J.; Schisterman, E.F. Age at Menarche and Metabolic Markers for Type 2 Diabetes in Premenopausal Women: The BioCycle Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, E1007–E1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Feng, Y.; Hong, X.; Wilker, E.; Li, Z.; Zhang, W.; Jin, D.; Liu, X.; Zang, T.; Xu, X.; Xu, X. Effects of Age at Menarche, Reproductive Years, and Menopause on Metabolic Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Diseases. Atherosclerosis 2008, 196, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trikudanathan, S.; Pedley, A.; Massaro, J.M.; Hoffmann, U.; Seely, E.; Murabito, J.M.; Fox, S.C. Association of Female Reproductive Factors with body Composition: The Framingham Heart Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Features | Total (n = 462) | Obesity | Hypertension | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 287) | Yes (n = 175) | p-Value a | No (n = 296) | Yes (n = 166) | p-Value a | ||

| Age (in years) | |||||||

| Median (IQR) | 51 (11) | 52 (10) | 52 (12) | 0.854 | 51.5 (10) | 53 (15) | 0.085 |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||||||

| No partner | 98 (21.2) | 56 (57.1) | 42 (42.9) | 0.252 | 55 (56.1) | 43 (43.9) | 0.065 |

| With partner | 364 (78.8) | 231 (63.5) | 133 (36.5) | 241 (66.2) | 123 (33.8) | ||

| Education level, n (%) | |||||||

| No formal education | 37 (8.0) | 19 (51.4) | 18 (48.6) | 0.095 | 20 (54.0) | 17 (46.0) | 0.172 |

| Primary education | 62 (13.4) | 35 (56.5) | 27 (43.5) | 33 (53.2) | 29 (46.8) | ||

| Lower secondary education | 153 (33.1) | 91 (59.5) | 62 (40.5) | 100 (65.4) | 53 (34.6) | ||

| Upper secondary education | 186 (40.3) | 129 (69.4) | 57 (30.6) | 127 (68.3) | 59 (31.7) | ||

| Tertiary education | 24 (5.2) | 13 (54.2) | 11 (45.8) | 16 (66.7) | 8 (33.3) | ||

| Monthly household income b | |||||||

| Median (IQR) | 526.4 (163.1) | 528.3 (159.3) | 529.5 (181.4) | 0.629 | 535.1 (167.3) | 524.1 (168.6) | 0.085 |

| Parity, n (%) | |||||||

| Nulliparous | 16 (3.5) | 12 (75.0) | 4 (25.0) | 0.397 | 11 (68.7) | 5 (31.3) | 0.864 |

| 1–2 | 293 (63.4) | 185 (63.1) | 108 (36.9) | 189 (64.5) | 104 (35.5) | ||

| ≥3 | 153 (33.1) | 90 (58.8) | 63 (41.2) | 96 (62.8) | 57 (37.2) | ||

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | |||||||

| No | 413 (89.4) | 263 (63.7) | 150 (36.3) | 0.045 | 269 (65.1) | 144 (34.9) | 0.988 |

| Yes | 49 (10.6) | 24 (49) | 25 (51) | 27 (55.1) | 22 (44.9) | ||

| Cigarette smoking, n (%) | |||||||

| No | 417 (90.3) | 259 (62.1) | 158 (37.9) | 0.141 | 275 (65.9) | 142 (34.1) | 0.731 |

| Yes | 45 (9.7) | 28 (62.2) | 17 (37.8) | 21 (46.7) | 24 (53.3) | ||

| Family history of obesity, n (%) | |||||||

| No | 373 (80.7) | 247 (66.2) | 126 (33.8) | 0.001 | 267 (71.6) | 106 (28.4) | 0.001 |

| Yes | 89 (19.3) | 40 (44.9) | 49 (55.1) | 29 (32.6) | 60 (67.4) | ||

| Family history of hypertension, n (%) | |||||||

| No | 405 (87.7) | 269 (66.4) | 136 (33.6) | 0.001 | 269 (66.4) | 136 (33.6) | 0.005 |

| Yes | 57 (12.3) | 18 (31.6) | 39 (68.4) | 27 (47.4) | 30 (52.6) | ||

| Age of menarche, n (%) | |||||||

| ≥12 years | 248 (53.7) | 168 (67.7) | 80 (32.3) | 0.007 | 172 (69.3) | 76 (30.7) | 0.011 |

| <12 years | 214 (46.3) | 119 (55.6) | 95 (44.4) | 124 (57.9) | 90 (42.1) | ||

| Age of menopause, n (%) | |||||||

| >45 years | 288 (62.3) | 194 (67.4) | 94 (32.6) | 0.003 | 188 (65.3) | 100 (34.7) | 0.486 |

| ≤45 years | 174 (37.7) | 93 (53.5) | 81 (46.5) | 108 (62.1) | 66 (37.9) | ||

| Age at Menarche | Overall | Age at Menopause | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤45 Years (n = 288) | >45 Years (n = 174) | ||||||

| PR (CI 95%) a | p-Value | PR (CI 95%) a | p-Value | PR (CI 95%) a | p-Value | p-Value for Interaction | |

| ≥12 years | Ref. | - | Ref. | - | Ref. | 0.008 | |

| <12 years | 1.36 (1.08–1.70) | 0.009 | 1.54 (1.09–2.16) | 0.013 | 1.26 (0.92–1.72) | 0.147 | |

| Age at Menarche | Overall | Age at Menopause | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤45 Years (n = 288) | >45 Years (n = 174) | ||||||

| PR (CI 95%) a | p-Value | PR (CI 95%) a | p-Value | PR (CI 95%) a | p-Value | p-Value for Interaction | |

| ≥12 years | Ref. | - | Ref. | - | Ref. | 0.118 | |

| <12 years | 1.34 (1.06–1.71) | 0.015 | 1.48 (1.02–2.13) | 0.036 | 1.28 (0.93–1.75) | 0.123 | |

| Age at Menarche | n (%) | Obesity | Hypertension | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR (CI 95%) a | p-Value | PR (CI 95%) a | p-Value | ||

| 12–15 years | 205 (44.40) | Ref. | - | Ref. | - |

| <12 years | 214 (46.30) | 1.38 (1.08–1.77) | 0.009 | 1.46 (1.13–1.89) | 0.004 |

| <15 years | 43 (9.30) | 0.75 (0.44–1.27) | 0.292 | 0.95 (0.56–1.61) | 0.861 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ibáñez-García, E.C.; Cureño-Díaz, M.A.; Mejía-Blanquel, M.A.; Castañeda-Márquez, A.C.; Leyva-López, A.; Orbe Orihuela, Y.C.; Trujillo-Martínez, M.; Castrejón-Salgado, R.; Ordoñez-Villordo, E.; Hernández-Mariano, J.Á. Early Menarche and Hypertension Among Postmenopausal Women: The Mediating Role of Obesity. Epidemiologia 2025, 6, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6040086

Ibáñez-García EC, Cureño-Díaz MA, Mejía-Blanquel MA, Castañeda-Márquez AC, Leyva-López A, Orbe Orihuela YC, Trujillo-Martínez M, Castrejón-Salgado R, Ordoñez-Villordo E, Hernández-Mariano JÁ. Early Menarche and Hypertension Among Postmenopausal Women: The Mediating Role of Obesity. Epidemiologia. 2025; 6(4):86. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6040086

Chicago/Turabian StyleIbáñez-García, Eunice Carolina, Mónica Alethia Cureño-Díaz, María Alicia Mejía-Blanquel, Ana Cristina Castañeda-Márquez, Ahidée Leyva-López, Yaneth Citlalli Orbe Orihuela, Miguel Trujillo-Martínez, Ricardo Castrejón-Salgado, Erick Ordoñez-Villordo, and José Ángel Hernández-Mariano. 2025. "Early Menarche and Hypertension Among Postmenopausal Women: The Mediating Role of Obesity" Epidemiologia 6, no. 4: 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6040086

APA StyleIbáñez-García, E. C., Cureño-Díaz, M. A., Mejía-Blanquel, M. A., Castañeda-Márquez, A. C., Leyva-López, A., Orbe Orihuela, Y. C., Trujillo-Martínez, M., Castrejón-Salgado, R., Ordoñez-Villordo, E., & Hernández-Mariano, J. Á. (2025). Early Menarche and Hypertension Among Postmenopausal Women: The Mediating Role of Obesity. Epidemiologia, 6(4), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6040086